Text

Macbeth!!!!

Repost @thercs

Our latest season is here – globally inspired stories, thrillingly told 💫

Co-Artistic Directors Daniel Evans and Tamara Harvey share what’s coming up on our stages later this year and next – stories from across the centuries and around the globe.

Join now to get Priority Booking, open for RSC Members from 10 June

Public Booking opens 25 June

Get acquainted with our latest productions, tours and transfers at the link in bio

#RoyalShakespeareCompany #Shakespeare #WilliamShakespeare #StratfordUponAvon #TikTokTickets

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This may never happen again. And it's a really amazing thing that we've been apart of. And I hope you guys get to have the same experience for a very long time. It's really very special and is not to be taken for granted."

—Outlander x Blood of my Blood: The Gathering

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was just another day in the Outlander casting office when a young Scot named Jamie Roy walked through the door. He was auditioning for the rather unremarkable role of Militia Man Number Two on the hit Starz series’ seventh season. The part got cut prior to final casting. So Roy tried out for another character a few months later, but didn’t book the gig. “I was really gutted because I thought this was going to be my break,” Roy tells Vanity Fair.

But the Outlander producers had far bigger plans for Roy. They were quietly developing Outlander: Blood of My Blood, a prequel about the parents of Caitríona Balfe’s Claire Beauchamp—a World War II nurse transported back to mid-18th-century Scotland—and Sam Heughan’s Jamie Fraser, the Highlander she falls for after traveling through time. As soon as they met Roy, the resemblance was clear: “We were like, ‘God, that guy looks a lot like Sam Heughan. That’s so crazy. Oh, do we save him [for the prequel]? But why are we saving him for something that we don’t even know is going to go?’” says executive producer Maril Davis, who has been on Outlander since its 2014 debut. “I would’ve felt bad if the prequel hadn’t come. But we did decide to save him.”

So, in what he calls “a wee bit” of an upgrade, Roy graduated from unnamed soldier to leading man. He stars on Blood of My Blood as Brian Fraser, Jamie’s future father—who, like his son, has no interest in courting until he meets the right woman: Ellen Mackenzie (Pennyworth’s Harriet Slater), the headstrong eldest daughter of a rival clan. Although pursued by many a suitor, Ellen is too busy grieving her father (Peter Mullan) and navigating a Succession-esque battle between her brothers Colum (Seamus McLean Ross) and Dougal (Sam Retford) to contemplate marriage. But Ellen’s familial loyalty is tested by her immediate attraction to Brian.

Sadhbh Malin, Sam Retford, Harriet Slater, and Séamus McLean Ross in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

Centuries later, Claire Beauchamp’s parents, Henry (Jeremy Irvine, who played a young Pierce Brosnan in Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again) and Julia Moriston (Star Wars and Mission: Impossible alum Hermione Corfield) are facing their own set of odds. While fighting on the frontlines during World War I, Henry sends a letter from the battlefield that finds its way to Julia, who covertly responds to the correspondence while working at a postal censorship office. Though separated by thousands of miles, their love blooms.

Jeremy Irvine in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

Hermione Corfield in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

But the new series isn’t inspired by any novels—which Davis sees as an opportunity. “With prequels, the challenge is you know exactly where you’re ending. But we have a lot of freedom in figuring out how to get there,” she says. “We don’t have a book series on this one, so we’re definitely not going to have that debate necessarily of, ‘Oh, this was in the book this way, but the show’s doing it a different way.’ But sometimes it’s nice to have the blueprint.”

Another hurdle: The original Outlander isn’t over yet. The sweeping period romance has run for seven seasons, with an eighth and final chapter still to come. Viewers don’t need to be totally caught up with its parent series to appreciate Blood of My Blood, but Easter eggs abound for those who are in the loop.

See, for instance, the character of Murtagh Fitzgibbons Fraser, played on the original series by Duncan LaCroix. Here, he’s Brian’s best friend, who once harbored an unrequited crush on Ellen. On Blood of My Blood, he’s jolly and upbeat—a big change for those who know that he’ll descend into darkness by the time Outlander unfolds. “Murtagh became the way he was because something happened to make him closed down, very cynical,” says Davis. “That was why it was so exciting when we cast Rory [Alexander], because he has such a twinkle in his eye. Like, ‘Oh, it’s fresh-faced Murtagh.’ It’s not-had-his-heart-broken, full-of-optimism Murtagh. And we get the ‘fun,’ in quotes, of seeing how he got that way.”

Rory Alexander and Jamie Roy in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

Jamie Roy and Rory Alexander in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

There is no official release date for the final season of Outlander, nor do we know yet how its 10-episode prequel might be merged into the first show’s time-traveling plot. “I don’t have a lot of say in when these things air. I’m sure some fans wish the mothership would finish before [the new series],” says Davis. “But the last season of Outlander wouldn’t have been ready to launch this early. There will be a lot of sadness with it ending. To have something else that will be completely different, but still scratch an Outlander itch, is helpful. Also, selfishly, I want to celebrate the end of Outlander on its own—and the longer we go without airing, the more it stays alive for me.”

At first, Davis assumed a potential prequel series would center solely on Jamie’s parents. But showrunner Matthew B. Roberts wanted to integrate Claire’s parents—who, as Outlander viewers and readers know, will get in a fateful car accident while on holiday in the Scottish Highlands when their daughter is only a young girl. Following parallel love stories made perfect sense to Davis. “Outlander isn’t just about Jamie—it’s about Jamie and Claire.”

Dividing the narrative between two couples has proved equal parts liberating and challenging. “You’re not killing your actors as much as we probably killed Caitríona and Sam in the first seasons,” Davis tells VF. “But on the other hand, it’s more difficult because you want to make sure both stories are unique. I feel like we’ve succeeded in doing that. They’re both very, very passionate love stories, but in a completely different way.”

Jeremy Irvine and Hermione Corfield in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

Like her costar, Hermione Corfield auditioned for a role on Outlander years before she was tapped to play Claire’s mother, Julia. “We’ve used a lot of crew members on both Outlander and BOB, and a lot of people did double takes whenever Hermione or Jamie would step on set because they did look so much like their predecessors,” says Davis. The typically blonde Corfield had never noticed a likeness to Balfe until she dyed her hair dark. “That’s when people started to go, ‘Oh wow, that is actually quite similar,’” Corfield says. “I’ve had a few people say we have the same mannerisms. I’m deeply flattered.”

Little is known about Julia and Henry in the Outlander universe, which was freeing for Corfield. “She has similarities to Claire, but her own personality and desires and dreams,” says the British actor. “London’s being bombed every day, and you don’t know what’s going to happen. She’s lost her parents in a similar way to Claire. So she’s a fiercely independent woman. There is a resilience and a need for survival that I found really interesting. She has to become harder in that harsh reality….I came to understand what she was capable of.”

There is a top-secret twist to Claire and Henry’s love story, but it’s safe to say that much of their courtship is a long-distance one—which makes any scene with Corfield and Jeremy Irvine in the same room feel utterly electric. “When they are separated, the audience hopefully remembers that palpable attraction and that fun and joy,” she says—“why they long for each other to this degree.”

Corfield and Irvine met on a 2016 film, remaining friends until they were cast as love interests nearly a decade later. “We make each other laugh a lot. I would describe it as a sibling-y relationship where we’re quite rude to each other,” she says. “So there’s already that chemistry. Knowing each other made all of the intimate stuff so easy and straightforward and comfortable, which is all you can really ask for.”

Jeremy Irvine and Hermione Corfield in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

Joining the world of Outlander, a franchise famous for its steamy, kilt-ripping love scenes, requires leads to get both emotionally and literally naked. Jamie Roy credits both his leading lady and the show’s intimacy coordinator, Vanessa Coffey, with fostering a safe space around the show’s sex scenes. “I trust Harriet with everything. And when you have that trust, you can let your guard down and be vulnerable,” he says. “It was definitely an experience, wearing all the intimacy stuff, like the pouches and everything. But once you’ve done a few takes, it does feel normal.”

Roy still remembers his meet-cute with Slater. “We had a chemistry read in the most awkward of situations. It was on a bank holiday in Scotland. Everybody was off”—even series director Jamie Payne, who Zoomed in to watch the actors read lines in a largely vacant studio. “Beforehand, I’d met with some actors that were fantastic, but I couldn’t find that spark for any of them. I thought I was doing something wrong,” says Roy. Then Slater entered the picture. “When I met her, something shifted. I was like, ‘Oh, this is what I’ve been missing.’ It was the only time that I’d ever read that scene the way that I did, and it was really special. I remember getting to the taxi after, and I text casting: ‘That’s the one, right?’”

Jamie Roy and Harriet Slater in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

When Roy got his third shot at booking an Outlander show, he tried to keep Sam Heughan’s voice out of his head. “My gut was to stay away from it and just do my own thing. Because when I got the audition, there was something about it that just spoke to me,” he says. “I remember thinking to myself, This is you in a nutshell. Then after the fact, Jamie Payne, the director of the first few episodes, said that Sam and I had so many similarities in the way that we were as people. So when people watch it, they’ll think, ‘Oh yeah, he’s picked that up from Sam,’ or whatever. But that’s just a happy coincidence.” Here are a few more coincidences: Roy’s actual middle name is Brian. And, strangely enough, “Jamie Roy” is a pseudonym that Jamie Fraser uses on Outlander.

At a certain point, even Roy got wary of all the comparisons. That changed when he and Heughan met for coffee midway through filming Outlander: Blood of My Blood. “We just clicked—talked about work for, I don’t know, five, ten minutes, and then started chatting about random stuff just as two bros would do,” says Roy. “And he’s still being so supportive to this day. Any time anything’s released, artwork or posters or trailers, he’s always one of the first people to text me: ‘Dude, it looks so cool. Congrats. Can’t wait to see it.’ And that means a lot.” Caitríona Balfe and Hermione Corfield also met for drinks while shooting their respective shows in Glasgow.

Jamie Roy in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

Harriet Slater in Outlander: Blood of My Blood.Courtesy of STARZ/Victoria Will

As Roy prepares for his life to change, he’s happy to share the pressures of leading a beloved franchise. “We all have four very distinct personalities. I like to think of it as a little circle: Each of us is a quadrant, and we fit together perfectly,” he says. “So there’s no butting heads. I always say the best things in life are the best until they’re shared, and then they’re even better.”

How much better could things be, really? “I was born and raised in Scotland, and I moved to America to make it. Then you move back for your big break—and you’re living five minutes away from where you went to school,” Roy says with a shake of his head. “There was something so poetic about that. It was like a full-circle moment of the child going away to become a man, and coming back with all the lessons he’s learned. Whether I’m a man, or still a little boy, I don’t know.” It seems Outlander has taught him something about the elasticity of time, an idea central to the franchise’s characters—past, present, and future.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Article 21 May 2025

Instagram entertainmentweekly

'Outlander: Blood of My Blood' will be delivering not one, but TWO love stories!

📷: Sanne Gault/Starz Entertainment

Posted 21 May 2025

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outlander x Blood of my Blood Cast Gathering

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

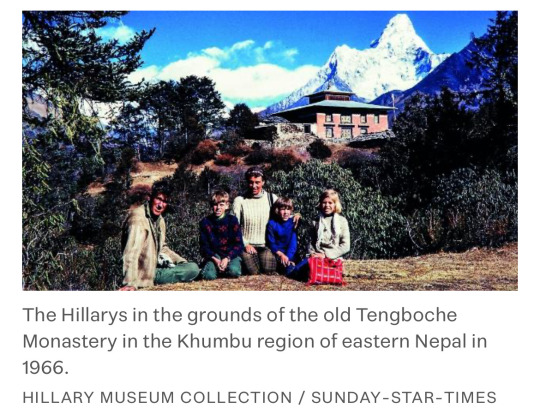

Tom Hiddleston's Everest 🗻Thriller ‘Tenzing’ Lands at Apple.

“Tenzing,” a film about the true story of Sherpa Tenzing Norgay’s 1953 trek to the summit of Mount Everest alongside Edmund Hillary, has been snapped up by Apple Original Films.

Casting is underway for Tenzing while “Loki” star Tom Hiddleston is set to play New Zealand mountaineer Edmund Hillary. On May 29, 1953, Hillary and the Nepalese Sherpa, Tenzing Norgay, set foot on the summit of Mount Everest, the highest point on Earth. They had succeeded where others had failed, and had survived a journey that had taken the lives of great explorers before them.

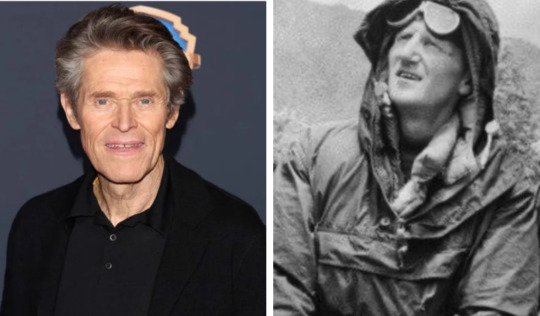

Willem Dafoe (“Eternity’s Gate”) as English expedition leader Colonel John Hunt. British army officer, mountaineer, and explorer John Hunt was best known for leading the 1953 expedition in which Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached the summit of Mount Everest, the highest mountain (29,032 feet [8,849 meters]) in the world. Hunt described the venture in the book The Ascent of Everest (1953).

The film, produced by Oscar-winning producer See-Saw Films (The King’s Speech) is gearing up on Tenzing, about the inspirational life of Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and his summit of Mount Everest in 1953 alongside fellow outsider New Zealander Edmund Hillary, and directed by Jennifer Peedom, is currently in production, with casting still underway for the role of Tenzing Norgay. Jennifer Peedom has a close relationship with the Tenzing family and the Sherpa community following her acclaimed documentary, Sherpa.

Tibetan born Tenzing Norgay, alongside New Zealand mountaineer Edmund Hillary, both outsiders on a British Expedition, defied insurmountable odds to achieve what was once thought impossible, reaching the summit of the world’s tallest mountain, Mount Everest,” reads the logline. After six previous attempts, Tenzing risked everything for one final venture.

The film will tell the story of the British expedition which in 1953 finally conquered the hitherto unconquerable and reached the top-most peak of the highest mountain in the world - Mount Everest. An unforgettable achievement.

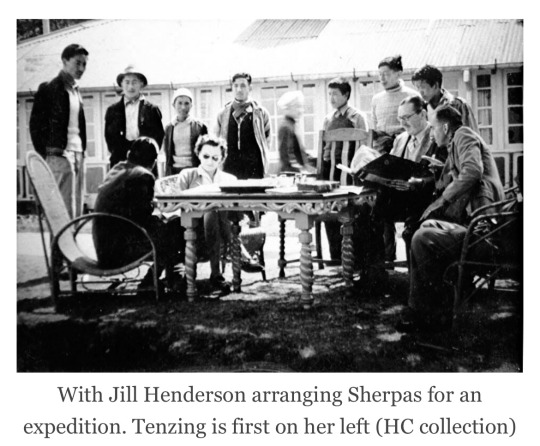

Caitríona Balfe is set to join the ensemble of Apple Films. Balfe will play ‘Jill Henderson,’ a friend of Tenzing who helped organise trips up Mount Everest. She was Honorary Secretary of the Himalayan Club between 1951–1955, and in this role she organised the Sherpa teams for several expeditions.. The Himalayan Club is an organisation founded in India in 1928 along the lines of the Alpine Club.

Jill Henderson was a key figure in the story of Tenzing Norgay and the 1953 Everest expedition. While not a direct family member, she played a significant role in encouraging Tenzing to participate in the expedition. But, Jill Henderson did not climb Mount Everest.

The Apple Original Films "Tenzing," is focuses on Tenzing Norgay's life and his summit of Everest with Edmund Hillary. Tom Hiddleston, Willem Dafoe, and the Himalayan cast are expected to bring the Sherpa’s story to life.

Lion writer Luke Davies is behind the screenplay. Producing is Liz Watts, Emile Sherman and Iain Canning for See-Saw Films, alongside Desray Armstrong, Peedom and Davies. (Apple and See-Saw have partnered on five seasons of the series Slow Horses.) Simon Gillis, David Michôd and Norbu Tenzing (son of Tenzing Norgay) will serve as executive producers.

Apple acquired the rights to the project in what was described as a “competitive situation” as Cannes kicked off. It is one of the first major deals to come out of the market.

Edmund Hillary (left) and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay reached the 29,035-feet summit of Everest on May 29, 1953, becoming the first people to stand atop the world's.

Two legends and Real hero's ✨

#EdmundHillary #TenzingNorgay #Everest #film #TomHiddleston #WillemDafoe #JohnHunt #Colonel #Britishexpedition #Sherpa #summit #mountaineer #JillHenderson #CaitríonaBalfe #AppleOriginalFilms #MountEverest #

Posted 6th May 2025

@kiaroa45 Yes, Sir Edmund and Louise Hillary founded the Himalayan Trust in the 1960s, they’ve inspired New Zealanders to give their time, money and support to help the people of Nepal through the Himalayan Trust.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

7x15 "Written in My Own Heart's Blood"

“Good luck to you, ma’am.”

And with that, he simply strode off toward the open doors of the church, not looking back. Jamie felt such a rush of fury that he would have gone after the man and dragged him back, could he have left Claire’s side. He’d left—just left her, the bastard! Alone, helpless!

“May the devil eat your soul and salt it well first, you whore!”

he shouted in Gàidhlig after the vanished surgeon. Overcome by fright and the sheer rage of helplessness, he dropped to his knees beside his wife and pounded a fist blindly on the ground.

“Did you just . . . call him a . . . whore?”

The whispered words made him open his eyes.

“Sassenach!”

EVEN PEOPLE WHO WANT TO GO TO HEAVEN DON’T WANT TO DIE TO GET THERE ~"Written in My Own Heart's Blood"

#outlander#outlander starz#the frasers#outlander series#outlanderedit#outlander fanart#jamie fraser#samheughan#claire fraser#jamie&claire#dr claire randall#claires wardrobe by episode#claire beauchamp#caitrionabalfe#outlander books#outlander season 7b#outlander 7x15

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outlander season 7 episode 08:" Turning points"

His languages boiled in his mind like stew, and he was mute. The first word to surface through the moil in his mind was the Gàidhlig, though.

“Mo chridhe,”

he said, and breathed for the first time since he’d touched her. Mohawk came next, deep and visceral.

I need you.

And tagging belatedly, English, the one best suited to apology.

“I—I’m sorry.”

67 GREASIER THAN GREASE~ An Echo in the Bone

#outlander#outlander starz#the frasers#outlander series#outlanderedit#outlander fanart#ian & rachel#rachel hunter#young ian#john bell#izzy meikle small#outlander season 7#outlander 7x08

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outlander 2×13 “Dragonfly in Amber”

《He... he survived. If that's true, then... I have to go back.》

#outlander#outlander starz#the frasers#outlander series#outlanderedit#outlander fanart#claire fraser#dr claire randall#claires wardrobe by episode#claire beauchamp#caitrionabalfe#outlander season 2#outlander 2x13

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

7x15 "Written in My Own Heart's Blood"

James Fraser is an honorable and courageous man.

Granted, he is a Scot and a rebel.

He's a damn fine swordsman.

He knows his horses.

And you and he,you're very much alike.

He's one of the best men I've ever met.

#outlander#outlander starz#the frasers#outlander series#outlanderedit#outlander fanart#jamie fraser#samheughan#david berry#wiliam & lord jonh#lord john grey#charles vandervaart#william ransom

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

#SamBirthdayChallenge

Day 4 edit in black&white

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 3 favorite interview 😜

#SamBirthdayChallenge

#outlander#outlander starz#outlander series#the frasers#outlander fanart#outlanderedit#samheughan#caitrionabalfe

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday to the one and only Sam Heughan 💗

109 notes

·

View notes