Julia | UNB 2020 | "Progress is measured by the speed at which we destroy the conditions that sustain life" - G. Monbiot

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Not sure what difference a few degrees can make? Here’s what a global temperature increase of 1-4°C actually looks like.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

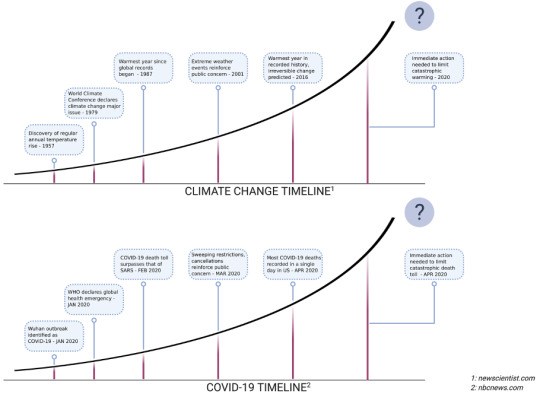

Could COVID-19 be the climate change tipping point we so desperately need?

These days, confined to our homes, our daily routines are likely to consist of a great deal more screen time than usual, so you’ve probably seen the hopeful tweets: the water in Venice is crystal-clear for the first time in years! Shaky iPhone footage shows that wildlife has started to return to places they haven’t been seen in some time! Some of these obviously have nothing to do with a “healing planet”, and many of these have been debunked: the clear canal waters in Venice are really the result of sediment settling due to the absence of water traffic, and many of these “returning” species had always been present in these areas if one knew where to look. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that there has been a significant decrease in global emissions, which have reportedly decreased by 25% since the start of the year in China, 20% in Spain and Italy, and as much as 50% in New York City alone. This is a good thing—but how optimistic ought we really be?

In my last blog post, I talked about the concept of “social tipping points” and how experts say we are in desperate need of a dramatic shift in social attitudes towards climate change if we have any hope of saving the planet. Is this global pandemic the kind of tipping point in favour of climate change these experts were talking about?

It is tempting to compare the attitudes towards the onset of this global pandemic to the those concerning the onset of climate change. Consider, for instance, that for weeks we were assured that there was no need to cancel vacation plans, conferences, and ceremonies, stating that simply being mindful of one’s surroundings and washing one’s hands frequently would be sufficient to protect against the virus. Then as warnings and harrowing anecdotes from scientists and medical professionals from Wuhan and around the world started to pour in at an intensifying rate, immediate school, university, and business closures were enforced across the country in a matter of days. Each day, it became evident that an incremental approach was not working: gatherings of 150 people or more were not recommended, quickly dropping down to 50, then only 5. The entire joint border between the Canada and the US is now shut down for the first time since the Canadian Confederation in 1867. We are witnessing what a global emergency really looks like.

Similarly, while the climate has been changing for some time, the warnings of many climatologists have come and gone for years without making major waves until very recently. Many people are starting to come around to the notion that this is a significant global issue requiring immediate action with more frequent catastrophic weather events, devastating wildfires, species loss, and marked environmental change. The speed and extent of the global response to COVID-19 have made some hopeful that we could see this kind of rapid action toward climate change if the threat it poses was treated as urgently.

However, many argue that the rapid global response to COVID-19 is no model for climate action. Still others caution that the response to COVID-19 was so sweeping and immediate because people understand that these lifestyle shifts are temporary, and that a “return to normal” is expected once the virus is contained or a vaccine becomes widely available. Contrastingly, climate action requires sustained, multi-generational change commitment to drastic lifestyle changes at the population level. Some are optimistic that this pandemic will inspire these changes, though many are apprehensive about this comparison, stating that pandemics and recessions are “hardly formulas activists should cheer, much less try to replicate”. Further, experts warn that while global carbon emissions will certainly decline this year, they might rebound significantly in future years, as evidenced already by the sweeping relaxation of environmental regulations on fossil fuels in China and the US in an effort to ease future economic recovery.

There are others that maintain that the kind of response we’ve seen to COVID-19 will be critical in the future with respect to climate action. The notion that climate change and this global pandemic go hand in hand is not novel: the Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme, Inger Anderson, has stated soberingly about the pandemic: “Nature is sending us a message,”. According to Anderson, the way humankind has been exploiting our global resources greatly facilitates the spread of pathogens from wildlife to humans. Amy Turner of the Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law has expressed that we are at an inflection point in the sense that we’ve seen such sweeping global action around the pandemic, adding “We also have the opportunity to reset the economy in a way that mitigates climate change”. In Canada, the federal government has been looking into investing in climate goals as a way to stimulate economic recovery: “When the recovery begins, Canada can build a stronger and more resilient economy by investing in a cleaner and healthier future for everyone,” said Moira Kelly, a spokesperson for Environment Minister Jonathan Wilkinson.

It is still not clear what the coming months have in store for us. This draconian reality we now find ourselves in could not have been foreseen even a few months ago. This is unprecedented, not only because of the universal nature of this threat but because, like climate change, it isn’t one that we can see. As we’ve seen, it is incredibly challenging to get people to unite against a threat that people don’t generally take seriously (or worse, one that many believe they are invincible to) until it is much too late. Hopefully, this pandemic will inspire more confidence in scientists and medical professionals as trust in many worldwide political figures fades with their struggle to manage this sweeping global crisis. Understandably, it is problematic to talk at length about the potential silver linings of this pandemic when it has brought so much grief, hopelessness, and uncertainty. But it has also reminded us of our unending capacity for generosity and compassion in trying times and what is possible when we take care of one another. This will be a critical perspective to have in the fight for climate action.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Polluters Pardoned Amidst Pandemic?

The world has been abuzz with news of the universal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been disheartening at the best of times and utterly terrifying at the worst. Though recently, news outlets have been reporting increasingly on a possible silver lining: the impact of this virus-induced global lockdown on the environment. As a result of some of the world’s biggest industries, airlines, and businesses shutting down, the world has experienced a notable decrease in carbon emissions. Emissions have decreased by 25% since the start of the year in China, and New York City has experienced a considerable plummet of 50% compared to emission levels in March of 2019.

While this news is undoubtedly encouraging, we may have to postpone our sighs of relief: just a few days ago, the US Environmental Protection Agency announced a sweeping relaxation of environmental regulations for industries across the US, among them some of the biggest polluters in the country. The new policy guidelines state that the agency will not be issuing fines to these major companies for exceeding previously determined limits for air, water, and hazardous waste pollution as industries report increased COVID-19-related layoffs and extensive restrictions. Until now, these companies have been required by law to disclose when they discharge significant levels of pollution into the surrounding environment.

You’re not alone if you think this doesn’t seem to add up. Why on Earth would companies need a widespread pardon to pollute if they’re effectively shut down? These regulations are indeed unprecedented, and even unreasonable, according to some observers and experts. Gina McCarthy, who led the E.P.A. under the Obama administration, described the policy as brazen and “nothing short of an abject abdication of the E.P.A mission to protect our well-being”. It is important to note that these new regulations, deemed by observers as responsible and sensible to downright insidious, are only in place (as of late) in the US. For now, one can only be hopeful that new regulations such as these don’t offset the positive environmental progress that we’ve been seeing around the globe.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triggers, tipping points, and tribulations: the need for more effective communication of climate change risks

These days, when one hears the words “climate change”, side effects can span from a dreadful anxiety about the end of life as we know it to blinding and incalculable rage. The words are also usually accompanied by even more distressing descriptors like “catastrophic”, “apocalyptic”, “irreversible”, and “worse than initially anticipated”. These words all have the same principal function: to alarm. Some academics argue that the use of this kind of alarmist language is tragically unproductive and has only served to increase cases of climate anxiety and bolster the activity of doomsday-prepping extremists and die-hard climate-deniers alike. Others maintain that downplaying the urgency of the climate crisis is more detrimental to society and that an alarmist (or, “realistic”) approach is our only existing hope for motivating the kind of social change we need—so how do we tease apart the truth in a tangled web of misinformation, alarmism, and myth? A subject of great public interest and anxiety is trying to determine whether we are closer than ever to inciting actual, positive change with respect to attitudes about our changing climate, or simply circling the drain. Social attitudes are powerful drivers of global change, but it is not clear how we can shift the discourse in such a huge way to actually motivate this change. To understand, it’s worth examining how close we really are to a “social tipping point” in favour of climate change, and whether or not alarmism is the most effective means of triggering a shift in social attitudes.

If you’ve ever taken a population ecology course, you might remember that in nature, populations growing at an exponential and unstable rate will eventually reach a critical threshold and be forced back to stable conditions. In a recent paper, researchers report that social tipping points (STPs) tend to mirror those that occur in nature, meaning that once a critical threshold is reached, biological systems have an inherent knack for reverting back to homeostasis on the edge of disaster. Social tipping points can occur after pressure builds gradually around a global social stressor until a resounding event triggers cascading changes that lead inevitably to a steady, stable state. Depending on what side of a debate you’re on, these changes can be good or bad. The research is built on an analysis of many similar historic events in human history—the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand as a tipping point that prompted World War I, or the famed 1952 Reader’s Digest article that exposed the beloved cigarette as a cancer-causing menace and caused the greatest decline in cigarette sales since the Depression. Some climate scientists believe that the world is on the brink of a social tipping point with respect to climate change. Unfortunately, scientists have no idea how to get there. The research is compelling but dense, and incredibly challenging to preempt or model as there aren’t any truly reliable historical comparatives—the issue of climate change is fundamentally different from any other major divisive social issue in human history. While it may be clear that a social tipping point in favour of climate change is our only hope in remedying the climate crisis, how do we expect to trigger it?

Global surges in climate activism have emphasized that the goal of these activists is often to amplify and dramatize climate change risks in an effort to prompt the creation of and influence existing climate policy and legislation. You wouldn’t be alone in thinking that this doesn’t seem so bad at first—how else would one who is rightfully apprehensive about a very real threat communicate their fears and motivate others to act? The authors of a 2007 study examining attitudes surrounding climate change caution against this kind of approach, James Risbey noted that this distressing but not-so-novel method of communicating climate change uses fear and shame as primary vehicles for the effectuation of positive change—an effort that is doomed to be counterproductive. When activist groups are called out for hyperbolizing the facts, it only strengthens the divide and climate activists and scientists alike are grouped together and stripped of credibility. More often than not, climate scientists are trying to stress that recent research into the adverse effects of climate change are justifiably alarming but only if we continue to do nothing to remedy our current emissions. This discourse differs from climate “alarmism” perpetuated by activist groups in that these changes aren’t thought to be apocalyptic or irreversible yet, but that the public needs to be alerted to the very real and substantial threat that climate change poses if immediate action isn’t taken. All things considered, it would appear as though climate scientists and academics aren’t being needlessly and recklessly alarmist about climate change – they’re simply voicing their very honest and legitimate opinions based on their exhaustive findings. The vendetta that most climate-deniers harbor against climate scientists has less to do with the actual science and more to do with how it is communicated.

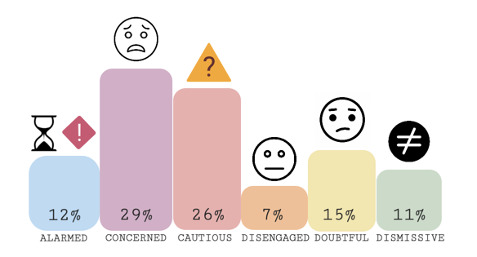

Recently, some very important measures have been taken to try and remedy the discourse surrounding climate change. The Yale University Program on Climate Communication has unveiled a new platform, called Constructive, the principal aim of which is to provide the public with crystal-clear, digestible, concise science concerning climate change. They understand that the climate divide is also an issue of trust: for many, the reassurance from their peers and political idols that there is no cause for alarm is enough. By providing an accessible platform and presenting scientific content and data in a simple and engaging manner, the YUPCC argues they can help people understand why exactly these findings are critical and what factors inherently place folks on either side of the partisan divide. They report that things already appear to be looking up: in the US, there’s been a recent surge of voter concern surrounding climate change (Figure I). The YUPCC are not alone in their belief that the active inclusion and encouraged participation of the public in the discourse is our best bet for mending the social divide on climate change. According to Risbey and his colleagues, when people are given full and open information about a threat and are included in the processes of defining and reacting to it, they are more likely to engage than if given only pieces of the story at a time or limited roles and responsibility. Bottom line: the critical factor is usually not the threat itself but whether it is conveyed in a credible and accessible (and not condescending and abrasive) way. In this way, researchers are optimistic that we can carve a clear and effective path forward.

Figure I: Attitudes towards climate change in the USA. Modified from data from the YUPCC: “Global Warming’s Six Americas”, March 2015.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

The authors borrow a definition of “social tipping point” (STP) from this paper, to wit: It is a point within a social system at which a small quantitative change can trigger rapid, nonlinear changes “driven by self-reinforcing positive-feedback mechanisms, that inevitably and often irreversibly lead to a qualitatively different state of the social system.”

As examples, the authors cite the writings of Martin Luther, which are alleged to have prompted a worldwide explosion of Protestant churches, and “the introduction of tariffs, subsidies, and mandates to incentivize the growth of renewable energy production,” which is said to have triggered exponential technology and cost improvements in wind and solar. These examples are contestable at best — we will return to the lack of good historical precedents later.

48 notes

·

View notes

Link

As we talked about in class: Know your audience, tell a story.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

The immutable undeniability of climate denial

In 2015, Senator James Inhofe, with the maniacal, blissful look of someone who knows they’re about to prove everyone wrong, brought a snowball into the US Senate. His rationale was glaringly simple, obvious even - how can the Earth be warming when it is so indisputably cold outside?

In Canada, episodes of outright and blatant climate change denial like these seem to be few and far between, but not unheard of: in September, Maxime Bernier, the leader of the People’s Party of Canada, told the Toronto Sun that “while the climate may be changing, this is not due primarily to human activity”. The day after the 2019 Canadian election, the hashtag #wexit (for “Western exit”) blew up on social media, as an organization called WexitAlberta began to share separatist sentiments while disputing numerous climate-related issues, among them: halting the building of pipelines, and the carbon tax.

All this begs the question: why are people in denial? What is fueling and intensifying this global spread of misinformation? This article explores the role of partisanship in the spread of misinformation focusing in particular on increased ideological polarization with respect to climate change. Their research has shown that this wide partisan divide on climate change can be reduced by drawing attention to the views of powerful politicians who explicitly acknowledge the scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change. This research is significant because the climate change divide remains one of the only major partisan issues that involves a dispute over scientific fact - facts which, as this paper emphasizes, may be no match for partisan loyalty. One important finding stood out: the study participants’ attitudes towards climate change could be swayed and concern about climate change increased in cases where their own parties made corrective statements about climate change and accepted the scientific consensus, but not if the statements came from non-partisan scientists or the opposing political party.

It’s important to note that while many climate change-denying statements made by politicians are obviously met with public incredulity by climate scientists, other politicians, and the general public, certain devastatingly misinformed opinions can still hold substantial and very real weight in some, particularly right-leaning, communities. The future of the climate crisis is uncertain, but this paper provides us with important research that has the potential to inform meaningful political discussion about how climate change is communicated, and how we can aim to unify an inexorably divided world against a very real, but not yet fully recognized, adversary.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the past five years alone, in fact, we have experienced the warmest temperatures of the last 140 years.

“We crossed over into more than 2 degrees Fahrenheit warming [roughly 1.1 degree Celsius] territory in 2015 and we are unlikely to go back,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute, in a recent press release.

“This shows that what’s happening is persistent, not a fluke due to some weather phenomenon: we know that the long-term trends are being driven by the increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.”

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi all!!

I’m Julia, and I’m a fourth-year bio student at a Canadian university interested in environmental activism, conservation, and climate change. I started this blog as part of a requirement for a course I’m taking in science communication, which explores techniques and exercises in effectively communicating and synthesizing complex current scientific research, particularly with respect to climate change. I’m so excited to share and report on the many impactful studies and papers about our changing climate that have impacted me recently, not to mention those I have yet to discover!

We know that scientific journals (and the newly published and rigorously peer-reviewed research within them) are already notoriously inaccessible - if access isn’t granted through your university or institution, you’re looking at an annual subscription of $200 for some of the major heavy-hitters like Nature and Science. When new research eventually trickles into the mainstream, it is usually because a media outlet has opened the floodgates in a usually careless attempt to assuage the general public’s thirst, serving only to further cement already polarized opinions.

An area of colossal contemporary interest (and unrest) that has not been communicated effectively to the general public is, of course, climate change, and the sordid back and forth between the public, lawmakers, congressmen/women, and even celebrities is not at all helpful, providing the perfect conditions for really harmful rhetoric to thrive. My goal in creating this blog is to try and learn what motivates productive dialogue between academics and the general public through the use of clear and accessible language that clarifies impenetrable and often intimidating science-talk. It’ll probably be like riding a bike, right?

Thanks so much for reading!! I look forward to engaging with all of you about some really interesting (albeit sometimes terrifying) research :)

Julia

9 notes

·

View notes