seaside-goldenrod

217 posts

environmental sci and GIS undergraduate (1 semester remaining) | they/them |

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

DR ADAM LEVY ClimateAdam ROSEMARY MOSCO

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

12 February 2024

Environmental engineer Dr. Tamer Al-Najjar continues working to rebuild Gaza even as the genocide rages on. On the struggles of working through a genocide, he writes,

Working amid war doesn't just entail working under fire; it's also about engaging in an internal battle over family provisions, such as water, food, and navigating through various crises amidst the war of starvation and thirst in the northern Gaza Strip!

Source: Tamer Al-Najjar via Stories on Instagram

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I loathe that word ‘pristine.’ There have been no pristine systems on this planet for thousands of years,” says Kawika Winter, an Indigenous biocultural ecologist at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. “Humans and nature can co-exist, and both can thrive.” For example, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in April, a team of researchers from over a dozen institutions reported that humans have been reshaping at least three-quarters of the planet’s land for as long as 12,000 years. In fact, they found, many landscapes with high biodiversity considered to be “wild” today are more strongly linked to past human land use than to contemporary practices that emphasize leaving land untouched. This insight contradicts the idea that humans can only have a neutral or negative effect on the landscape. Anthropologists and other scholars have critiqued the idea of pristine wilderness for over half a century. Today new findings are driving a second wave of research into how humans have shaped the planet, propelled by increasingly powerful scientific techniques, as well as the compounding crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. The conclusions have added to ongoing debates in the conservation world—though not without controversy. In particular, many discussions hinge on whether Indigenous and preindustrial approaches to the natural world could contribute to a more sustainable future, if applied more widely.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Despair is paralysis. It robs us of agency. It blinds us to put own power and the power of the earth. Environmental despair is a poison every bit as destructive as the methylated mercury in the bottom of Onondaga Lake. But how can we submit to despair while the land is saying “Help”?

Restoration is a powerful antidote to despair. Restoration offers concrete means by which humans can once again enter into positive, creative relationships with the more-than-human world, meeting responsibility that are simultaneously material and spiritual. It’s not enough to grieve. It’s not enough to just stop doing bad things.’

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

"There's no wildlife here. The land is barren and stripped from farming chemicals"

I just saw two blue herons fly super low over our house, which means they've been fishing in the creek behind us, which means there's fish there. Which means there's bugs to feed the fish and algae to feed the bugs, which means the water and soil is worth something damnit.

Yes, I'm sorry the suburb isn't the grand, sweeping swath of uninhabited land that you so desperately crave but would learn to loathe, but saying that the land here is barren and that there's no wildlife here and that there's nothing to salvage- that's a You problem. Nature might be struggling, but against all odds it is at least trying.

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

It was about 15°F this morning and when sunlight hit the cold water mist began to form.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

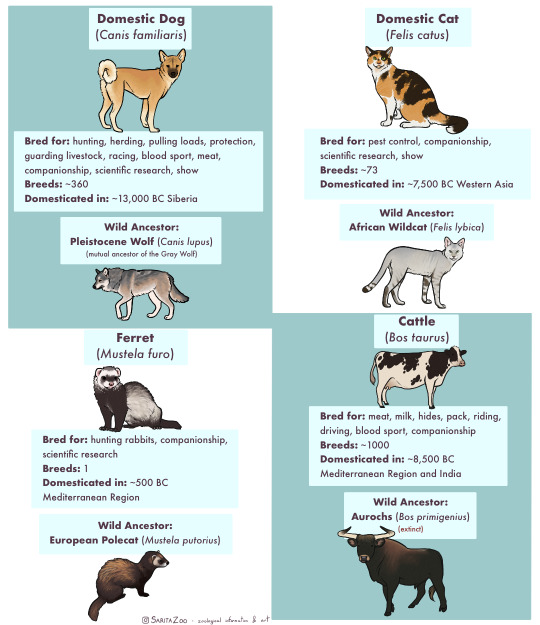

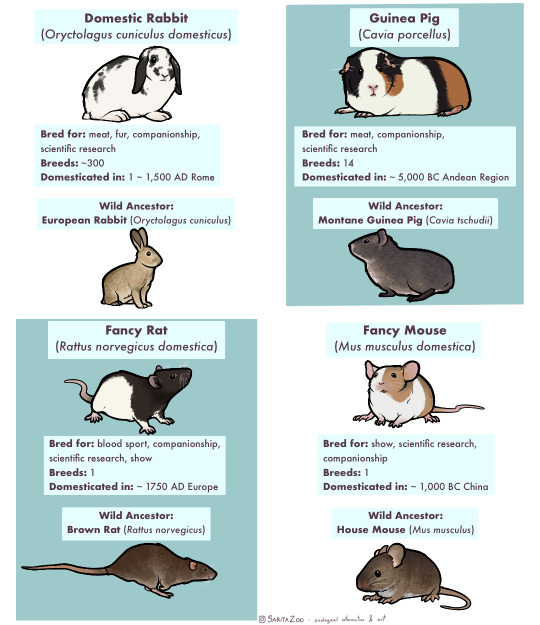

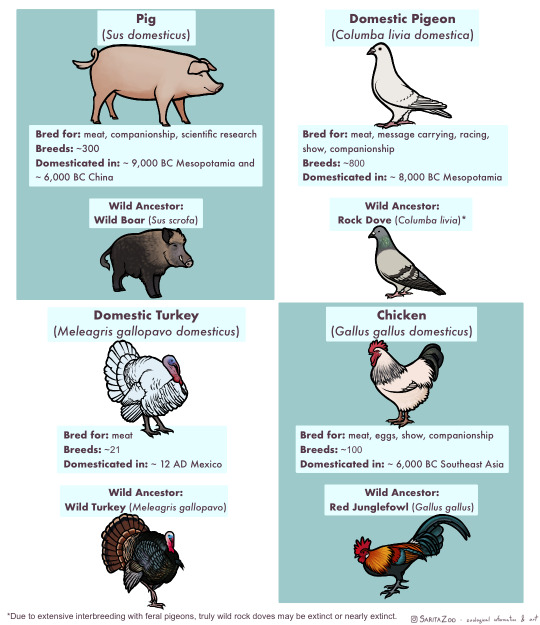

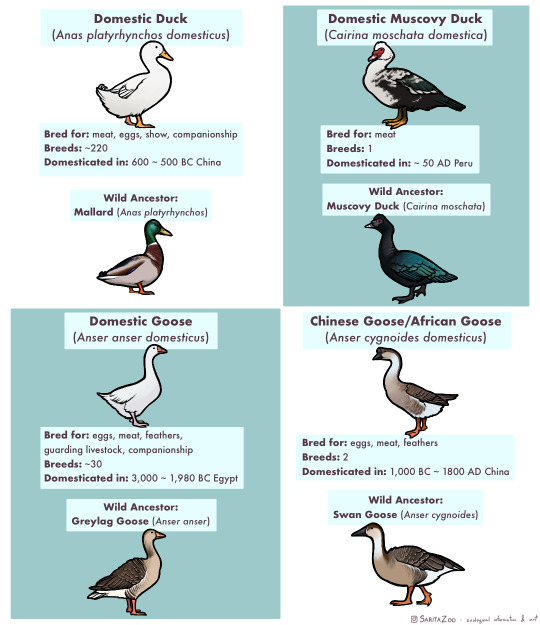

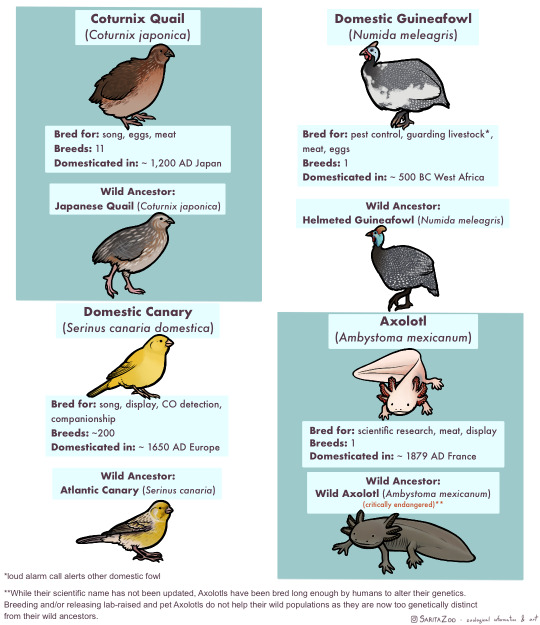

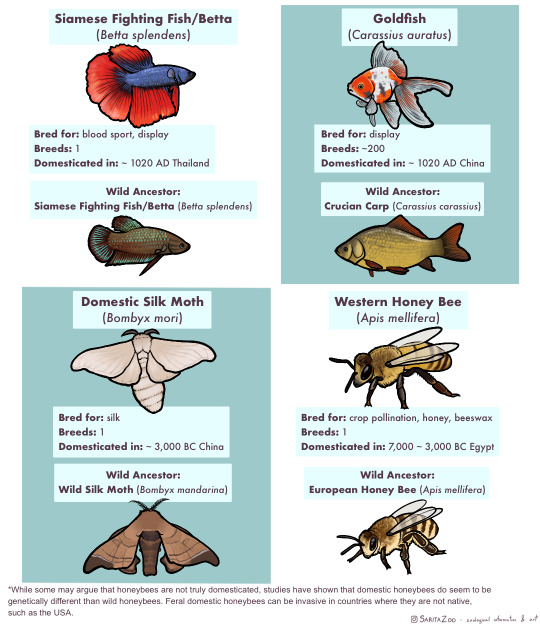

Phew. This one took, uh… a bit longer than expected due to other projects both irl and art-wise, but it’s finally here. The long-awaited domestic animal infographic! Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough space to cover every single domestic animal (I’m so sorry, reindeer and koi, my beloveds) but I tried to include as many of the “major ones” as possible.

I made this chart in response to a lot of the misunderstandings I hear concerning domestic animals, so I hope it’s helpful!

Further information I didn’t have any room to add or expand on:

🐈 “Breed” and “species” are not synonyms! Breeds are specific to domesticated animals. A Bengal Tiger is a species of tiger. A Siamese is a breed of domestic cat.

🐀 Different colors are also not what makes a breed. A breed is determined by having genetics that are unique to that breed. So a “bluenose pitbull” is not a different breed from a “rednose pitbull”, but an American Pitbull Terrier is a different breed from an American Bully! Animals that have been domesticated for longer tend to have more seperate breeds as these differing genetics have had time to develop.

🐕 It takes hundreds of generations for an animal to become domesticated. While the “domesticated fox experiment” had interesting results, there were not enough generations involved for the foxes to become truly domesticated and their differences from wild foxes were more due to epigenetics (heritable traits that do not change the DNA sequence but rather activate or deactivate parts of it; owed to the specific circumstances of its parents’ behavior and environment.)

🐎 Wild animals that are raised in human care are not domesticated, but they can be considered “tamed.” This means that they still have all their wild instincts, but are less inclined to attack or be frightened of humans. A wild animal that lives in the wild but near human settlements and is less afraid of humans is considered “habituated.” Tamed and habituated animals are not any less dangerous than wild animals, and should still be treated with the same respect. Foxes, otters, raccoons, servals, caracals, bush babies, opossums, owls, monkeys, alligators, and other wild animals can be tamed or habituated, but they have not undergone hundreds of generations of domestication, so they are not domesticated animals.

🐄 Also, as seen above, these animals have all been domesticated for a reason, be it food, transport, pest control, or otherwise, at a time when less practical options existed. There is no benefit to domesticating other species in the modern day, so if you’ve got a hankering for keeping a wild animal as a pet, instead try to find the domestic equivalent of that wild animal! There are several dog breeds that look and behave like wolves or foxes, pigeons and chickens can make great pet birds and have hundreds of colorful fancy breeds, rats can be just as intelligent and social as a small monkey (and less expensive and dangerous to boot,) and ferrets are pretty darn close to minks and otters! There’s no need to keep a wolf in a house when our ancestors have already spent 20,000+ years to make them house-compatible.

🐖 This was stated in the infographic, but I feel like I must again reiterate that domestic animals do not belong in the wild, and often become invasive when feral. Their genetics have been specifically altered in such a way that they depend on humans for optimal health. We are their habitat. This is why you only really see feral pigeons in cities, and feral cats around settlements. They are specifically adapted to live with humans, so they stay even when unwanted. However, this does not mean they should live in a way that doesn’t put their health and comfort as a top priority! If we are their world, it is our duty to make it as good as possible. Please research any pet you get before bringing them home!

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

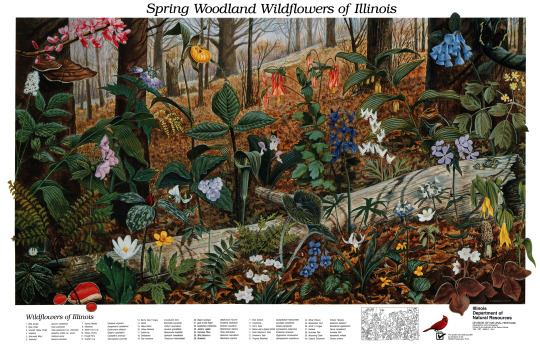

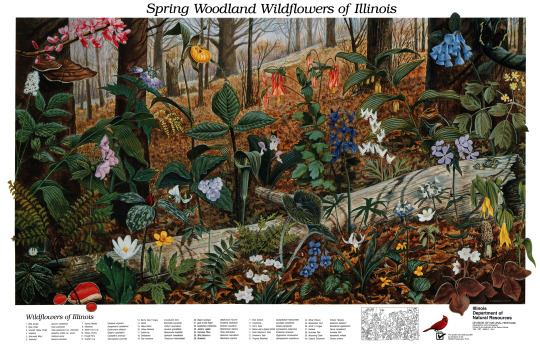

Spring Woodland Flowers of Illinois poster by Robert F. Eschenfeldt (1930-2005)

I'm slowly collecting these gorgeous posters from the 70s/80s that the Department of Natural Resources put out. I've had luck with nature centers digging in their back closets

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

In light of Duolingo laying off its translators, here are my favourite language apps (primarily for Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, and te reo Māori).

Multiple Language

Anki is a flashcard programme and app that's not exclusively for languages. While making your own decks is ideal, you can also download shared decks for most languages.

If you're learning Japanese, specifically, Seth Clydesdale has websites for practicing alongside Genki's 2nd or 3rd editions, and he also provides his own shared Anki decks for Genki.

And if you're learning te reo Māori, specifically, here's a guide on how to make your own deck.

TOFU Learn is an app for learning vocabulary that's very similar to Anki. However, it has particularly excellent shared decks for East Asian languages. I've used it extensively for practicing 汉字. Additionally, if you're learning te reo Māori, there's a shared deck of vocabulary from Māori Made Easy!

Mandarin Chinese

Hello Chinese is a fantastic app for people at the HSK 1-4 levels. While there's a paid version, the only thing paying unlocks is access to podcast lessons, which imo are not really necessary. Without paying you still have access to all the gamified lessons which are laid out much like Duolingo's lessons. However, unlike Duolingo, Hello Chinese actually teaches grammar directly, properly teaches 汉字, and includes native audio practice.

Japanese

Renshuu is a website and app for learning and practicing Japanese. The vast majority of its content is available for free. There's also a Discord community where you can practice alongside others.

Kanji Dojo is a free and open source for learning and practicing the stroke order of kanji. You can learn progressively by JLPT level or by Japanese grades. There's also the option to learn and practice kana stroke order as well.

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

Spring Woodland Flowers of Illinois poster by Robert F. Eschenfeldt (1930-2005)

I'm slowly collecting these gorgeous posters from the 70s/80s that the Department of Natural Resources put out. I've had luck with nature centers digging in their back closets

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Big fan :) You're an environmental lecturer, right? I recently got into a debate with someone about rewilding in the UK, and the clash with farmers and agriculture. To me, this is a no-brainer - I absolutely do feel for farmers losing their livelihoods, and I think there needs to be a system to help them transition to something else, but also, the planet is dying. But you explain things well, so I wondered if you have thoughts? Particularly on the Welsh side of things. Thank you in advance!

Hah. I literally have a lecture on this. Or, well, a chunk of a lecture, anyway; so yes! I have thoughts. I'll use those notes, and stick a big reference at the end in case you want to read more

I'll talk about this specifically from the Welsh perspective, okay so:

The rewilding project in Wales is the Cambrian Wildwood, launched in 2004ish by a guy who bought an abandoned farm in the northern end of Mid Wales with the express intention of rewilding it. The aim is to convert some 7000 acres, and the initial mission statement said they'd reintroduce wolves and lynx. That's the project I'm going to talk about, because it's a great case study for how to spectacularly fuck something up (and eventually realise you've spectacularly fucked up, and do something about it.)

These are the Cambrian Mountains:

When looking at that, there are two competing viewpoints that are relevant here:

The Cambrians are ecologically depleted. Their biodiversity has crashed since the Second World War, when modern farming methods were introduced. Environmentally, there is a perception of emptiness and degradation.

The landscape is a glorious one that has been shaped by the human actions taken on it for generations, as we are a shepherding culture – culture and land are inextricably intertwined.

That's a big fundamental difference! Two people can look at that same photo, and see something diametrically opposed. But there's more lying on it, so you also need to understand the socio-political background.

Socio-Political Background

(I know! Headings! So professional)

A lot of rewilding – Cambrian Wildwood included – is taking place in areas where farming is declining for various political/socio-economic reasons, so this can be ENTIRELY FAIRLY seen as yet another threat. This goes hand in hand with rural migration and community decline, too.

In Wales, we’re mostly rural, and characterised by extensive upland livestock farming (sheep in particular). Most farms are small to medium family-run setups. ON TOP OF THAT, the vast majority of Welsh farmers are Welsh-speaking, and the right to operate a farm the ‘traditional’ way without UK government oversight is seen by Welsh Nationalists as an important post-colonial act.

Many of them didn’t even like the National Parks being set up, as they were seen as an English outsider imposition that ignored the working nature and cultural history of the land. Remember: the farmed uplands are often seen as a heartland of Welsh identity, and those have historically been intentionally destroyed by UK central government land management decisions (e.g. Tryweryn, Elan, Claerwen, etc)

“Over the past half century we have witnessed the arrival of countless environmental fundamentalists… seemingly oblivious to the fact that their new-found paradise is already occupied by people whose connection with the land is deep rooted, dates back thousands of years, and is embedded in their language and culture.” (Nick Fenwick [Farmers’ Union of Wales] 2013)

SO IT’S CULTURALLY DICEY

(And in my opinion an incredibly stupid idea to go and give it a primarily English name with a Welsh translation as an afterthought but that is Elanor’s Opinion and not Scientific Fact)

(But fr fr if you ever have to get involved in these sorts of projects you will go a long way if you have the basic respect of learning the Welsh names and pronouncing them right rather than lazily expecting everything to be in English sorry sorry I digress)

From the Cambrian Wildwood’s Mission Statement on their website, their objective is:

“To rewild or restore land to a wilder state to create a functioning ecosystem where natural processes dominate by carrying out habitat restoration, removing domestic livestock, and introducing missing native species as far as feasible.”

Can you see the controversial bit of the statement

Can you see the bit where they directly say they want to remove domestic livestock

Jesus Christ

Cultural Differences

AND THEN HERE'S THE BIGGER PROBLEM

‘Culture’ in Welsh is diwylliant – literally, a ‘lack of wildness’. There is no direct translation into Welsh for the term ‘rewilding’ – the closest you can get is anialwch or diffeithwch, which mean ‘wilderness’ in the sense of ‘desert’ or ‘wasteland’. So right off the bat, if you tell a Welsh-speaking farmer that you want to rewild the place, what they hear is "We want to make it dangerous and empty and degraded."

A related concept is cynefin - knowing one’s ‘patch’ and the feeling of belonging associated. The term has its roots as a description of the way grazing animals know their area of mountain land, but it is also used to describe how people come to form an intimate experiential knowledge of place - and specifically, a Welsh farmer's cultural attitude.

Basically, Welsh literature and oral traditions speak of a relationship with the land, not a separation and longing for an untouched wilderness. Farmers feel this especially keenly. Culturally, this is a big part of why they do it – they’re rooted to the land, and therefore to their identities.

“Interviewees conveyed this by referring to areas proposed for rewilding as being comprised of “a quilt of cynefinoedd: interwoven stories, the layered and collective place-making of families and individuals over-generations, co-constituted with the physical landscape” (Wynne-Jones, Holmes and Strouts, 2018)

So, to them, rewilding is erasing and disregarding these stories. To them, this is not just a land-use change, but the latest colonial attack. They've known the family who lived on that farm for generations - every birth, marriage, death, joy, triumph, loss, everything. You are saying that you are going to strip that family, all those stories, all those people out of that land, to be forgotten.

…

However. There is a counterpoint to this.

Many farmers taking this view have therefore identified themselves as the only “truly Welsh” people in the debate, accusing environmentalists as being outsiders. The problem with this being, most of the environmentalists involved with the project are also Welsh; so who the fuck are they to say who is or is not Truly Welsh? It's what we on the internet would recognise as gatekeeping, with a big side order of No True Scotsman fallacy.

Also this quote sums it up well:

“Sheep farming in this country goes back a few hundred years. I think if you go deep enough into our culture and ancestry, we have a really deep native relationship with wild forest areas and with the wild animals that are native to this country…I just don’t agree that sheep farming is really part of our traditional culture.” (WWLF Interview [15] 2016) (Wynne-Jones, Holmes and Strouts, 2018)

This is also a fair point. It is true that upland sheep farming, the way we now practice it, is only a few hundred years old, and at the current intensity only a few decades (since WW2).

On top of which, there has been plenty of exploration over the years of farmers as being a government-subsidised landed gentry, which I won't go into here, but it also contains some fair points.

In truth, all of it and none of it is true. It’s far more complex and nuanced than either side might want to believe.

Solutions So Far

This is an ongoing project and they're still learning and changing new things and stuff, but a big thing they did was get someone in to basically be a mediator and listen to both sides, because Jesus, those sides were not listening to each other.

But to date:

They actually worked with a first-language Welsh speaker (WHY DID THEY NOT DO THIS FIRST I'm sorry I'm fine). Originally the Welsh translation of the project was Tir Gwyllt – wild land. But given that Welsh connotations with gwyllt are something out of control or dangerous, Coetir Anian has been chosen – anian refers to a sense of natural order and creation, a sense of health and vitality. Similarly, ‘rewilding’ is being translated as ‘di-ddofi’ – ‘de-taming’. This acknowledges the labour and culture taken to tame it, and just suggests an avenue for discussing some relaxation of farming practice in appropriate locations rather than, you know, releasing packs of wolves directly into sheep pens

In online materials and in community engagement events where traditional storytellers and musicians have performed to celebrate the Wildwood, the trustees have drawn heavily from Welsh myth in the form of the Mabinogion. Enormous amounts of the Mab lovingly and respectfully feature wild woods and wild animals. The emphasis is therefore on how wilderness is also part of Welsh identity – and arguably a much older part, going back to the Celts. (This is clever, in my view, but something to approach with care - it's rarely a good idea to play the game of "What's the most Welsh". But so far it's been done sensitively)

Land purchased for the project has so far been wholly limited to that available in the public domain. The main site, Bwlch Corog, was empty and unfarmed for six years before purchase, which has been stressed in all media interviews and releases; this is important, because farmers do have a sense of "Productive land is being stolen by environmentalists".

Large predator reintroductions have largely been abandoned. Lynx and wolves are no longer on the agenda. It’s possible they’ll be included in the future, but it is acknowledged as currently impractical (both from clashes with farmers and lack of habitat).

Instead, they’ve supported smaller species reintroductions, such as the Vincent Wildlife Trust’s pine marten translocations, and some proposed red squirrel ones.

Bwlch Corog is to be managed as an experimental plot that farmers are encouraged to engage with.

Assessing the potential for new income streams (from improved tourism and educational activities) rather than just the ecological benefits – this has become central to the project, and the emphasis is on how this might benefit farming communities and keep them together. This has been huge, and has also been successful in rewilding schemes in Europe.

Tensions are a lot lower now than they were ten years ago, but ultimately the problem was a bunch of outsiders came in and decided they knew best without listening to anyone else's point of view, and that meant both sides really dug their heels in. Much better now.

Ultimately... yes, I am in favour of rewilding, in a general sense. But I think it needs to go hand in hand with supplying farmers with the necessary subsidies to transition back to more traditional and sustainable farming methods, and the two elements run side by side. You can't do one without the other, not if you want them to succeed. The Pontbren Project is a great case study for how a farmer-led scheme can successfully aid them economically while also improving environmental outcomes, and we need to learn and incorporate more lessons from it when discussing this kind of landscape-level management.

Also, with land management in general, I think you're a fucking idiot and dangerously arrogant if you think you can get anything done without all stakeholders being on board. And potentially wandering down the ecofascism path, circumstances dependent.

Anyway, those are my thoughts. Source:

Wynne-Jones, S, Holmes, G & Strouts, G (2018), 'Abandoning or Reimagining a Cultural Heartland? Understanding and Responding to Rewilding Conflicts in Wales - the case of the Cambrian Wildwood.' Environmental Values, vol. 27, no. 4.

825 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm guessing that as a graduate student you have read a zillion and one documents and books and papers and things in your field. Would it be outrageous to ask for recommendations/your favorites? I'm really interested in learning more about the history of Native land use and food systems in the midwest (which I suppose is a very long history, I'd be happy learning about any time period), prairie ecology, and the current outlook for native plants and pollinators (and conservation recommendations). Even one recc for each would be amazing. Feel free to postpone this ask if you're too busy! P.S. can't wait to read your dissertation.

This is a big ask, and I get a lot of these types of asks! In the future it'd be nice if people were more specific about their interests and not asking about general, huge topics. There's a level that you can and should be googling yourself! Many academic papers are online for free through sites like academia.edu and I'm not a search engine!

General answer if you're interested in this range of topics is Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass. She comes from the midwest and writes some on prairie and the book is all about Indigenous science stewardship.

Otherwise, the topics you're asking for don't have one single source that will tell you everything you're looking for. People make small studies of one community, one ecosystem, one plant. Whether it's ecology or ethnobotany, there's no one making compendiums of info, especially not in the midwest. That's why I do the work I do, but even what I do is imperfect. Be suspicious of anyone who/any text that claims to be comprehensive on a huge, complex subjects; they probably are bsing you.

Indigenous Land Mgmt:

Two good recent papers:

The subject of indigenous wild management is more intensely covered in California (M. Kat Anderson) and Vancouver (Nancy J. Turner). Those two authors are great for both nuts and bolts chat and philosophical perspectives about how people have lived in and altered and restored their ecosystems.

A compelling academic book on the subject is Roots of Our Renewal: Ethnobotany and Cherokee Environmental Governance by Clint Carroll, which is just as much about philosophy, knowledge production and protection and community building, as plants.

Prairie Conservation Practices:

Like I said above, currently published stuff is about very specific interactions and focuses, like a particular pollinator group in a particular plant. What you're looking for, a generalist summary of the field, doesn't really exist.

If you're looking for plant lists and how-tos Tallgrass Restoration Handbook or the Tallgrass Prairie Center Guide. Do not go for Ben Voigt. If you're looking for a general conceptual entry to Midwest conservation/restoration, there's Ecological Restoration in the Midwest

If you're looking for general recommendations for free, Xerces.org is the resource for bee-friendly landscaping and planting.

If you live near a University or Arboretum or Botanic Garden, this is the kind of thing where you should just browse the shelves near the books I've recommended! Chances are you have free access to the libraries, if not the ability to check the books out yourself!

199 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Klinse-Za caribou herd is rebounding towards healthy population numbers, even as Canadian caribou populations overall trend downwards. The herd has increased from 38 to over 100 animals in under a decade.

This incredible increase is due to stewardship by the West Moberly First Nations and Saulteau First Nations and sets a precedent for methods that could be used to bolster caribou numbers throughout Canada.

“This is truly an unprecedented success and signals the critical role that Indigenous Peoples can play in conservation. I hope this success opens doors to collaborative stewardship among other communities and agencies.”

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

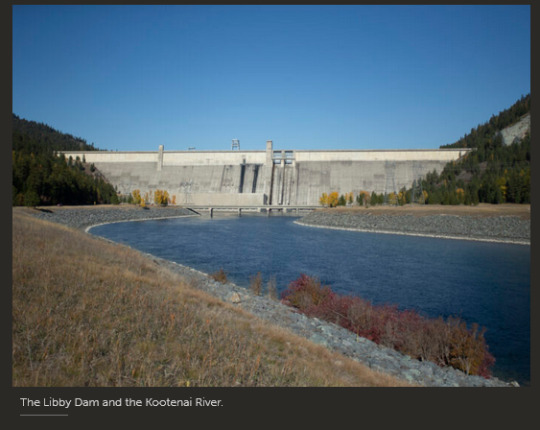

The Narwhal just published a really thorough and easy-to-understand look at the ongoing selenium poisoning and land management issue of the Kootenai/Kootenay River. The article includes maps, graphs/charts, and photos of the landscape. The article also provides a good look at the conservation work of the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and the Ktunaxa Nation; I’ve tried to excerpt those passages here, below.

Basically, the story is that industrial coal mines at Elk Valley near Fernie in interior British Columbia poison the Kootenai watershed, which includes land/water in Montana and Idaho. Everyone knows about the poisoning, but since the river crosses an international border and involves 2 different US states, government agencies can’t or won’t limit mining companies or fix the issue because of legal jurisdiction issues. The river flows through the globally-rare inland temperate rainforest region/biome, and the river system is home to the highly endangered, nearly-extinct land-locked variation of the Kootenai River white sturgeon. Management of the pollution across an international border has led to conflict between Indigenous communities, BC provincial, Montana/Idaho state, Canadian federal, and US federal agencies. The river is already imperiled by the existence of the Libby Dam, the drainage of wetlands, forest-clearing, and tourism/land-development from nearby Fernie and Spokane-Coeur d’Alene. The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho manages a fish hatchery to help native burbot and the white sturgeon.

For years, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Ktunaxa Nation have tried to appeal to both Canadian federal and US federal authorities to ask for some kind of trans-boundary/international collaboration. In 2021, the Ktunaxa Nation asked BC and Canadian federal land managers to suspend all permitting processes for new coal mines in the region. Despite Indigenous resistance, Canada continues to accept proposals for new coal mines in the region.

All text and photos below are from the article.

——-

Scientists already know where the selenium is coming from: a string of enormous metallurgical coal mines in B.C.’s Elk Valley. Parties on all sides, including Teck Resources, which owns the mines, are keen to stem the flow of contamination. But efforts to address pollution soon run up against economic interests […]. The mines are allowed to release selenium at levels well beyond what the province considers safe for aquatic life, and even as experts warn of a growing threat to fish and other aquatic life, regulators are weighing proposals for new coal mines in the valley. […]

Pollution from the mines has become an increasingly contentious issue between Canada and the United States, where downstream ecosystems, already burdened by human development, are now feeling the added strain of selenium. The scope of the contamination is extensive. Even a few hundred kilometres downriver, there are fears that increasing selenium pollution threatens the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho’s decades-long effort to restore white sturgeon and burbot populations in the Kootenai River. “To see any of that work be reversed or effectively cancelled out would be a tragedy to our people and the nature we hold so dear to our hearts,” says Gary Aitken Jr., Kootenai Tribe of Idaho’s vice chair.

Journalists from The Narwhal traced the flow of selenium from the mines down the Fording River, along the Elk, into the Koocanusa reservoir and south across the border until it pours over Montana’s Libby Dam. From there we followed the Kootenai River, which rushes and gurgles before tumbling over the Kootenai Falls on its way to Idaho, where it meanders through farmlands on its way back north, crossing back into B.C. (where the spelling changes from Kootenai to Kootenay) before eventually merging with Kootenay Lake. At each stop, we found people deeply concerned about the threat selenium poses to fish in these rivers. […]

The Koocanusa reservoir, a vast human-made lake spanning the international boundary, collects water from both the Kootenay and Elk Rivers. For years, a joint B.C.-Montana working group involving experts, representatives from Indigenous governments, Teck and multiple state and provincial government agencies […]. The hope was that the B.C. and Montana governments would adopt a single selenium standard for Koocanusa. After years of work, Montana moved forward on its own. The state officially adopted the more stringent selenium standard for Koocanusa of 0.8 parts per billion in February 2021 after securing approval from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. But for months, it was “pretty much crickets from north of the border,” says Sexton, who has worked with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes on this issue for more than a decade. […]

The Ktunaxa Nation Council, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho are all part of the broader Ktunaxa Nation, whose traditional territory covers parts of the region known today as B.C., Alberta, Montana, Idaho and Washington State. While the impacts of selenium and other contaminants from the mines are a significant concern throughout the Kootenai River watershed, for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, Lake Koocanusa and the Kootenai River downstream of the Libby Dam, are a particular focus. […]

Some 90 kilometres downriver, across the state line, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho has pressing concerns about the threat selenium poses to endangered white sturgeon and burbot populations. These fish hold spiritual and cultural significance for the tribe, says Aitken Jr., Kootenai Tribe of Idaho vice-chair. […]

The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho has been working for more than three decades to restore white sturgeon and almost 20 years to rebuild burbot populations, species that may have been wiped out long ago from the Kootenai River if not for the tribe’s conservation aquaculture program.

At its Twin Rivers Hatchery, near the confluence of the Moyie and Kootenai Rivers, tiny prehistoric-looking sturgeon swim slowly along the bottom of large, round tanks. […] But neither sturgeon nor burbot are close to self-sustaining — the Tribe’s ultimate goal. […] Eventually, Hoyle says, she hopes to see a site specific selenium standard established for the Kootenai River downstream of Libby Dam, one that’s more protective of the fish populations the tribe is working so hard to protect and rebuild. The challenge is that it’s governments north of the border that have authority over the source of the contamination — the coal mines back in Canada.

The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Ktunaxa Nation, have for years called for this pollution issue to be referred to the International Joint Commission, a body created under the Boundary Waters Treaty signed by Canada and the U.S. in 1909. […] The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and Ktunaxa Nation have sent repeated letters to federal government officials in Washington and Ottawa asking for the issue to be referred to the joint commission or for some other transboundary framework […]. Neither B.C. Environment Minister Heyman nor the federal spokesperson would say whether their governments support calls for an International Joint Commission reference.

Last summer, the Ktunaxa Nation asked the B.C. and federal environment ministers to suspend all environmental assessments for new coal mines in the Elk Valley.

“We will no longer accept the ‘business as usual’ approach to coal mining,” the Ktunaxa Nation Council’s letter says. “Ktunaxa laws and customs require us to act as stewards of our our ʔamak ȼ wuʔu [land and water] […].”

“Unfortunately, a legacy of major coal mines in Qukin ʔamakʔis, approved without our consent, now threatens our ability to uphold our responsibilities as Indigenous title holders and caretakers of this area within ʔamakʔis Ktunaxa.” […]

Despite those efforts, selenium continues to leach from the piles of waste rock that have built up over more than a century of mining. It continues to flow from the Fording River, into the Elk and south through Koocanusa. It pours over the Libby Dam into the Kootenai River, where it cuts through mountain valleys and rushes over the Kootenai Falls. It meanders through canyons and farmland in Idaho on its way back to the B.C., where it empties into Kootenay Lake — far west of where it first drains into the rivers of the Elk Valley.

——-

Text by: Ainslie Cruickshank. All photos by: Jesse Winter. Text and photos from: “How pollution from Canadian coal mines threatens the fish at the heart of communities from B.C. to Idaho.” The Narwhal. 23 April 2022.

#land back#ktunaxa nation#kootenai tribe#confederated salish#environmental racism#indigenous stewardship

564 notes

·

View notes

Text

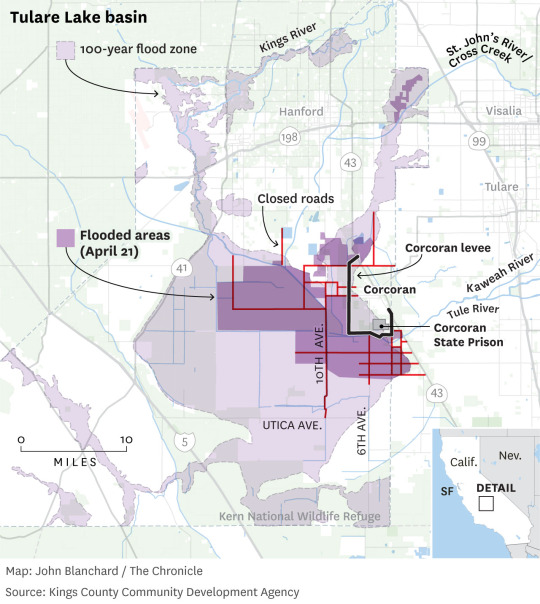

California's lost Tulare Lake returns, some want to make it permanent

More than 100 square miles of roads, farms and homes in the formerly dry lake bed between Fresno and Bakersfield remain submerged in the entrenched floodwaters. Additional land is expected to go under through summer as record Sierra Nevada snow melts into rivers that fill the lake. Already, damages are in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

While landowners as well as local, state and federal officials are focused on keeping major towns and infrastructure dry, the broader issue of whether there’s a better way to manage water in the basin looms. Some say the recent flooding is making the case to more naturally accommodate incoming water, perhaps broadening river plains, restoring old wetlands and, more dramatically, ensuring a permanent revival of Tulare Lake.

This year, the lake is likely to be even larger than it was 40 years ago and therefore linger as long, or longer. The snowpack in the nearby Sierra, which is just beginning to melt, is more massive — measuring three times the average in the region. Additionally, the floor of the valley has sunk in recent years as a result of heavy groundwater pumping by farms, known as subsidence, potentially creating new areas for water to collect.

Read More

70 notes

·

View notes