Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

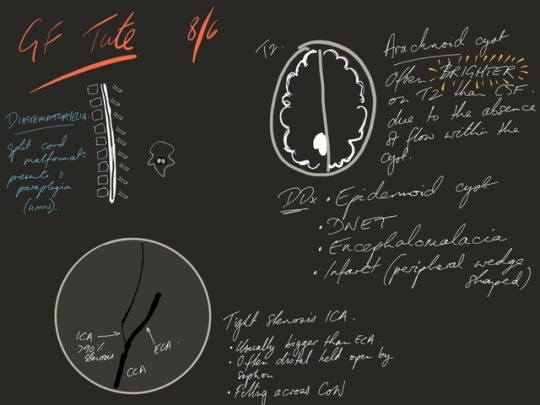

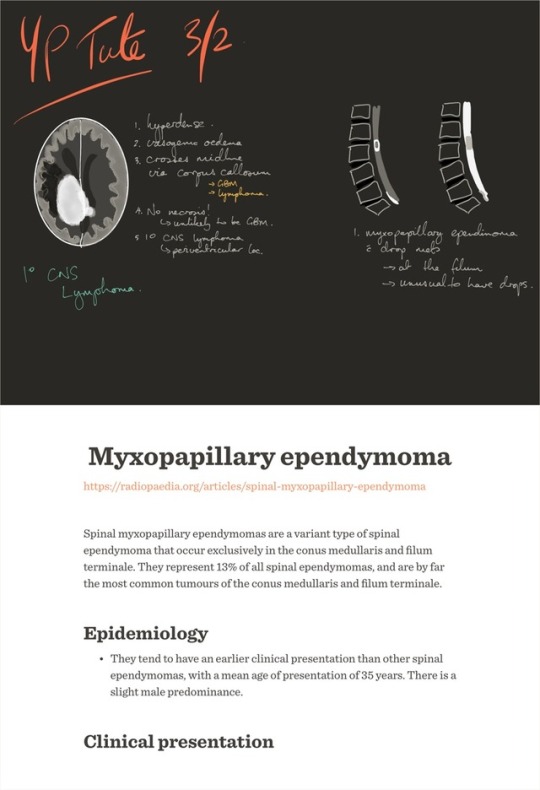

Myxopapillary ependymoma https://radiopaedia.org/articles/spinal-myxopapillary-ependymoma Spinal myxopapillary ependymomas are a variant type of spinal ependymoma that occur exclusively in the conus medullaris and filum terminale. They represent 13% of all spinal ependymomas, and are by far the most common tumours of the conus medullaris and filum terminale. Epidemiology • They tend to have an earlier clinical presentation than other spinal ependymomas, with a mean age of presentation of 35 years. There is a slight male predominance. Clinical presentation • The most common presenting symptoms are low back, leg or sacral pain. Up to 25% of patients may present with leg weakness or sphincter dysfunction. • They may occasionally present as a subarachnoid haemorrhage 8. Pathology • They are thought to arise from the ependymal glia of the filum terminale or conus medullaris. The vast majority are intradural and extramedullary, however, rarely they occur in the extradural space. They are generally classified as WHO grade I lesions, however occasionally CSF dissemination occurs and multiple lesions are seen in 14-43% cases 4. Macroscopic appearance • They are typically multilobulated and encapsulated. They often have associated haemorrhage, and may calcify or undergo cystic degeneration. Microscopic appearance • Histologically, they contain papillary elements in a myxoid background, admixed with ependymoma-like cells. Radiographic features ◦ Plain radiograph / CT • If they become large, myxopapillary ependymomas may expand the spinal canal, cause scalloping of the vertebral bodies and extend out of the neural exit foramina. ◦ MRI • Smaller tumours tend to displace the nerve roots of the cauda equina; larger tumours often compress or encase them 8. Signal characteristics ◦ T1 • usually isointense • prominent mucinous component occasionally results in T1 hyperintensity • haemorrhage and calcification can also lead to regions of hyper- or hypointensity ◦ T2 • overall high intensity • low intensity may be seen at the tumour margins because of haemorrhage (myxopapillary ependymomas are the subtype of ependymomas that are most prone to haemorrhage 8) • calcification may also lead to regions of low T2 signal ◦ T1 C+ (Gd) • enhancement is virtually always seen • the enhancement pattern is typically homogeneous, however they can have a variable enhancement pattern that, in part, depends on the amount of haemorrhage present Treatment and prognosis • Myxopapillary ependymomas are generally slow-growing, although some sacral and presacral lesions behave aggressively and metastasise to lymph nodes, lung and bone. • They can often be excised completely. In these cases, prognosis is excellent. If the tumour has extended into the subarachnoid space and surrounded the roots of the cauda equina, resection is often incomplete and local recurrence is likely. Differential diagnosis ◦ Differential diagnosis of a small conus and filum terminale myxopapillary ependymoma includes: • spinal schwannoma: often indistinguishable from ependymoma • spinal paraganglioma ◦ Differential diagnosis of a large myxopapillary ependymoma that causes sacral destruction: • aneurysmal bone cyst: involving the spine • chordoma • giant cell tumour: involving the spine #madewithpaper / fiftythree.com

0 notes

Photo

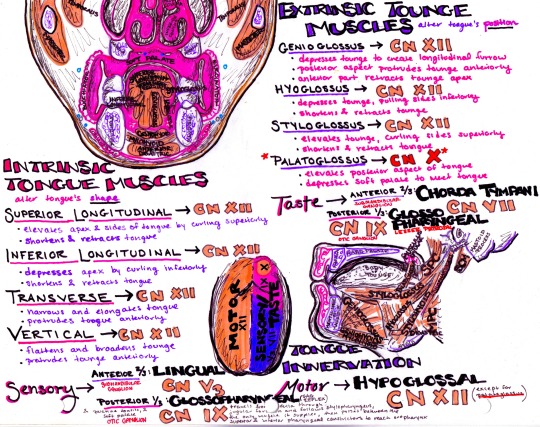

The extrinsic muscles of the tongue! (Pardon my terrible spelling)

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

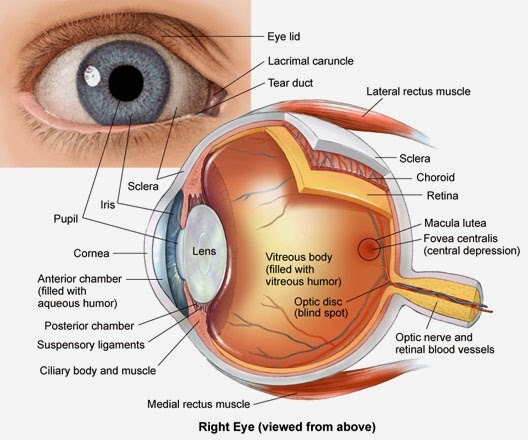

The anatomy of the orbicularis oculi muscle is one of the two major components that form the core of the eyelid and is an important muscle as it deals with facial expression. This muscle lies in the tissue of the eyelid and causes the eye to close or blink. The eyelids act to protect the outer surface of the globe from local injury and also aid in regulation of light reaching the eye. Learn More

www.learninghumananatomy.com

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

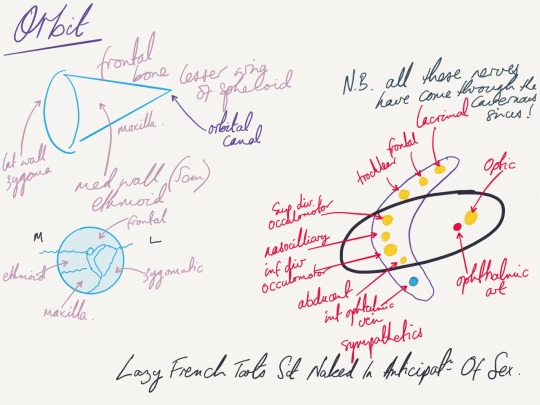

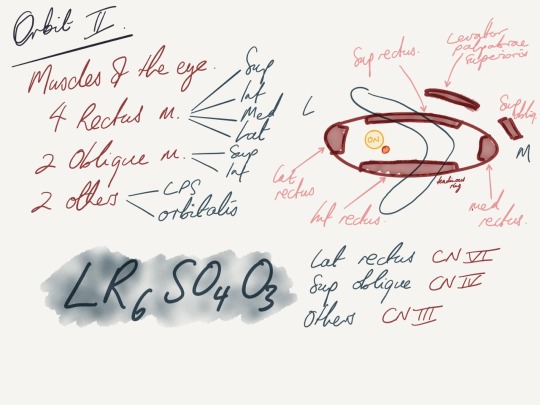

Orbit notes 2

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

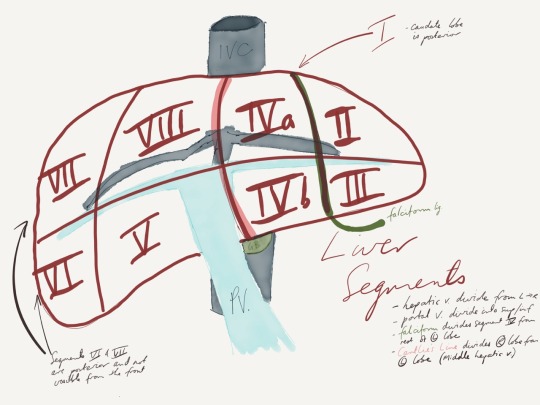

Describe the liver segments. The liver is divided into 8 segments, each of which is a functional unit with its own portal vein, hepatic artery and biliary drainage. Each segment has a portal vein, hepatic artery and bile duct centrally and vascular outflow peripherally through the hepatic veins. In general the right and left portal veins divide the liver into superior and inferior segments while the hepatic veins divide the segments sagitally. - The right hepatic vein divides the right lobe into anterior and posterior segments. - The middle hepatic vein divides the liver into right and left lobes (this plane runs from the IVC to the gallbladder fossa) Cantlie's Line - The falciform divides the left lobe into a medial (segment IV - can be IVa and IVb) and a lateral (segment II & III) - The caudate lobe (segment I) sits posteriorly against the IVC (I t should be noted that the caudate lobe often drains directly into the IVC via its own veins) - The portal vein divides the liver into superior and inferior segments, in the right lobe dividing V & VI from VII & VIII and in the left lobe dividing II from III and IVa from IVb

1 note

·

View note

Photo

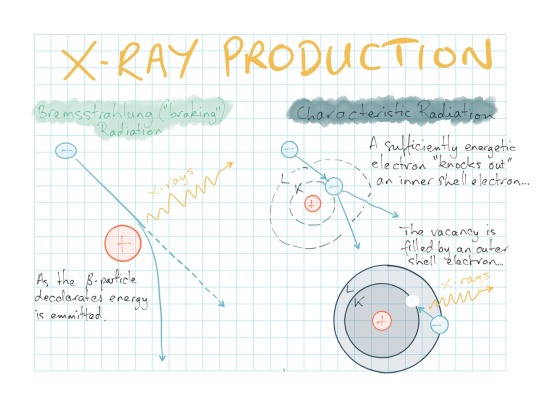

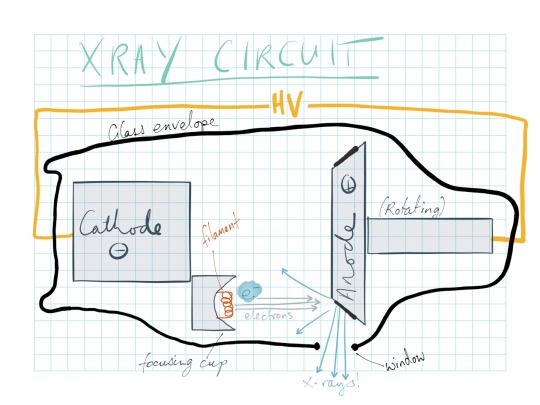

#madewithpaper / fiftythree.com Basic diagram of an X-ray circuit.

0 notes

Text

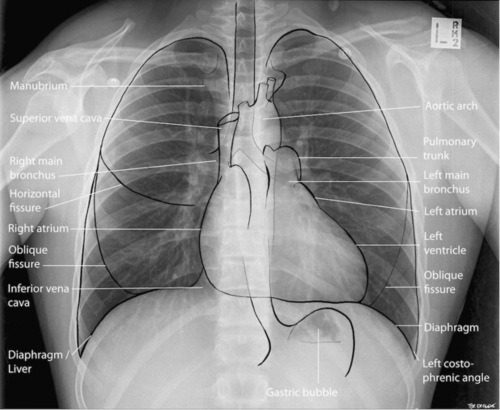

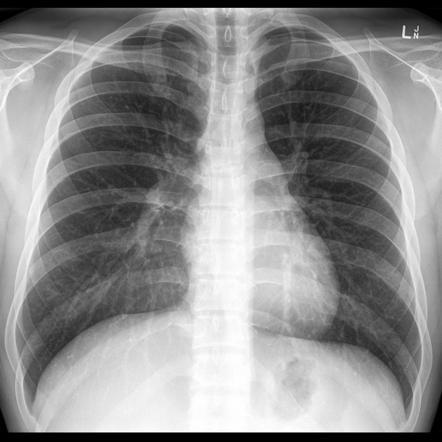

Great introductory primer to chest x-ray interpretation.

Basics for the Wards: Reading a Chest X Ray

Chest X-rays (aka CXR) are one of the most basic imaging studies done in medicine. Almost every hospitalized patient has one and you will see hundreds of them by the time you finish med school.

But it was be super easy to get distracted by the huge glaring pathology (like a giant mass) that you miss other pathology (like a broken clavicle). So, like with reading EKGs, it’s best to have an algorithm you run through for every CXR so you don’t miss anything.

Disclaimer: Again, this is just a general introduction with some basics to help you start out on wards. There is a lot more to interpreting chest x-rays that what I mention, that is why radiologists are awesome.

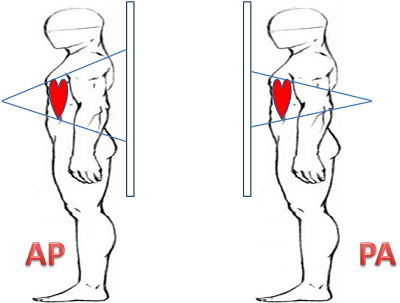

First: What is the view- is it AP (front to back) or PA (back to front)? Lateral CXRs are obvious.

PA

AP

If the patient is able to stand, a PA view is generally preferred. AP is generally when patients are confined to the bed- also you usually cannot diagnose cardiomegaly from an AP view because the heart is almost always bigger in this view. How do you tell the difference between them? Look at the scapula- in a PA view the scapula are usually clear of the lungs, whereas in an AP view the two generally overlap. Sometimes the clavicle positioning can be a good clue too- see the differences between the two?

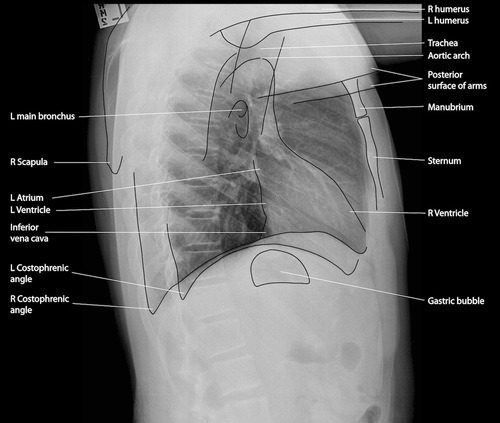

Lateral

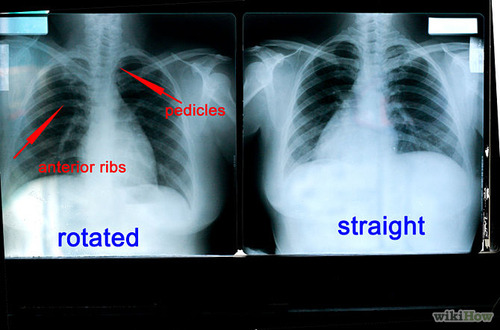

Second- what is the quality, because that can have a major effect on your interpretation. A good mnemonic is RIP.

- Rotation - Measure the distance of each clavicle from the spinous processes at that level, if they are equidistant then the patient is not rotated.

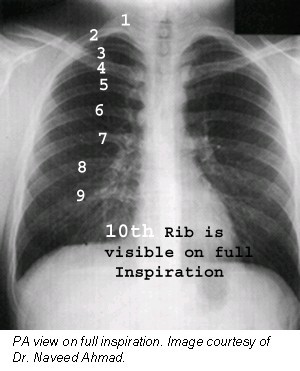

- Inspiration - If you can count nine posterior ribs within the lung fields before you reach the diaphragm, then there was enough inspiratory effort. Poor inspiratory effort will look like the patient has an airspace disease. Note: Posterior ribs = more apparent, look more horizontal. Anterior ribs = less visible, 45ish degree angle towards feet

- Penetration - With flawless penetration, you should be able to see the thoracic spine through the heart.

Underpenetration= Left hemidiaphragm and left lung base will not be visible, and pulmonary markings will appear more prominent than they actually are. Ahhhh!!!!

Overpenetration= what is even happening here

OK, now you’re ready to see what is going on with the patient. I suggest the systematic approach, which has the handy mnemonic ABCDE= airway, bones, cardiac, diaphragm, everything else (lungs). I’m not going to go into all the pathology associated with everything, because that would take forever.

- Airway: Is the trachea patent and midline? Can you see the mainstem bronchi and the carina? If there is an endotracheal tube in place, make sure that it is 3-4 cm above the carina. Also check to make sure the mediastinum is not deviated or abnormally wide.

- Bones: Is anything broken or dislocated? Any lytic lesions?

- Cardiac: How clear is the cardiac silhouette? Is the heart enlarged? What about all the vessels- the aorta, SVC, IVC, etc.

- Diaphragm: Is the right side higher than the left but not like wayyyy too much? Are the costophrenic angles clear (if not, could be an effusion!)?

- Everything else: NOW you can look at the lungs. Is there an infiltrate or a mass? What about pneumothorax? Also check for you friendly neighborhood gastric air bubble, it’s supposed to be below the diaphragm.

Easy enough, right? Good luck!

3K notes

·

View notes