Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Gestures of Sara Hagale

instagram

There's the matter of the limbs. Egon Schiele drew his limbs as frames around breasts, genitals. Ribboning and lithe, they proclaim the contours of a naked torso peeking from beneath flowy garments. Whether the subject is clothed or not, Scheile's drawn limbs suggest nakedness. A turned wrist, a bony shoulder shrugged toward the lips, and an outward-turining knee all stress an erotic point of view.

I saw Schiele works in person in The National Art Center, Tokyo, during the Vienna on the Path to Modernism show. Let's just say that it stirred up torrential emotions, rivalled only in intensity by my encounter with Matisse works.

instagram

Sara Hagale does similarly, trading in eroticism for an unapologetically childlike simplicity. I discovered her on Instagram, where she has a considerable following. My little sister's best friend reposted a Hagale drawing (shown below) to her own Instagram story, and I froze the image, laying my thumb on the screen, totally spellbound. Since then, I've fallen into rabbit holes of scrolling endlessly down Hagale's page, gripped by the limitless experession in her little crystalline cartoons.

instagram

A talent shared by Hagale and Schiele is the capacity to disarm a viewer with the enormity of mood communicated via the slightest of sketches. It takes tremendous dexterity to achieve this. Unencumbered by the elaborate worldbuilding present in the oil paintings of the Old Masters, line drawings have a candid affect, presenting an image so distilled that it stuns with clarity of thought.

(Book recommendation, by the way: The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera).

0 notes

Text

Hayley Williams: Petals for Armor

Hayley Williams' solo venture is a sister to Massive Attack's Mezzanine, both albums being the perfect accompaniment to a cup of black tea. Guided by a dirgy non-energy, she works through the emotional sauces of grief and desire by way of an experimental pop atmosphere reminscent of cinammon and dried flowers-- a yawping, tentatively distressing 1 a.m. brew.

0 notes

Text

Adrianne Lenker & Buck Meek: b-sides

I believe in the earnest, lucid tremor that is Adrianne Lenker’s voice. I want to crawl into the cinematic scope of her stripped-down musicality. Her songs have a people-smell: musty, like a heap of clothes in a wooden cabinet, tactilely angelic but unmistakably human. A stunning comfort I didn’t know I needed, this gentle EP courts mundanity, with nothing but a nudge of the fingertips.

0 notes

Text

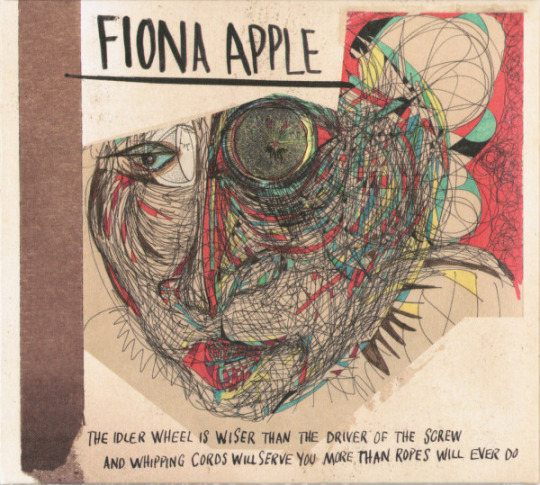

FIONA APPLE: The Idler Wheel is Wiser Than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do

This record is incisively person-shaped, and it’s scowling, bathrobe-clad, and ready to pace back and forth all night in the ennui-prone mythscape of a dreary hotel room. Grunts, wails, and tart, nearly unmelodic thuds are the vehicles for Fiona Apple’s maximal, penetrating lyrics. Her venom as an artist is unquestionable.

0 notes

Text

Lana del Ray aka Lizzy Grant

Glittering like moonlight on the sea, scorching and rebellious as a bonfire, despairing and all-encompassing as quicksand. This record is a perfect apparition that has eaten me alive. If I ever get to listen to other music again it will be through the prism of what Lana del Rey has taught me.

This is the same Lana del Rey that made Ultraviolence, but then it isn’t. Ultraviolence drew from the billowy, twangy-guitar rock of the 70′s, offering shrill ragetunes that sound like they were thrust underwater and then photographed with a glowy skin Instagram filter. “I’m a dragon, you’re a whore/ don’t even know what you’re good for,” she scoffs in Fucked My Way Up to the Top, a lithe track about...I’m not entirely sure. What I know is that Ultraviolence satisfied me entirely. It’s supremely atmospheric and swept me off my feet from the get go. The rhyme from Cruel World— “Get a little bit of bourbon in ya/ get a little bit suburban then go crazy”— was so sticky and irresistible; the consonants bubbled and gurgled the guitars shrieked and the drums crashed broadly, rhythmically shovelling away the apprehension I naturally have when giving an album a first listen. I thought the album had peaked with the first song. Ultraviolence was a Hall of Fame of del Rey’s most romanticizable traumas.

Aka Lizzy Grant is less a Hall of Fame and more of a scrapbook. The songs are each the size of a Polaroid, and are just as hazy. We’re shown an iteration of Lana del Rey that does not draw from an engulfing, on-the-nose opulence. Quite the opposite: “I don’t mind livin’ on bread and oranges, no, no/ But I got to get to and from where I come/ and it's gonna take money to go” she sings as a hushed, lean-in confession in Pawn Shop Blues.

This record is a perfect apparition that has eaten me alive.

1 note

·

View note

Text

AURORA: Infections of a Different Kind

Norwegian artist and dryadic force of nature Aurora Aksnes blazes with widescreen production, visceral melodies, and reinvigorating heart.

0 notes

Text

A mothership of gorgeous descriptors: Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose

Yes, very much the mood.

My lovely copy with cat bites and ink stains:

Quiet afternoons with you lying on the floor. The tea is boiling. Our slippers outside, in disarray, tucked beneath the belly of a sleeping purple cat. Infinite, delicate feeling. The rain is set to come.

If you’re attracted to fragmented, lyrical writing like this, then Too Much and Not the Mood may just be for you. Durga Chew-Bose is a literal flower. Reading this compilation of personal essays, I could not help but hear Debussy’s “Arabesque no. 1″ wafting through the air as dandelion florets floated through the orange air, landing on teacups, high school yearbooks, vinyl records, and ancient dresses, falling with the softness of an inarticulable, specific nostalgia that is roused solely by scent.

This book sings with a fierce generosity. Chew-Bose offers a bloom of her personal history, and humbly recounts the cultural and familial histories from which her life is inextricable. Ethnically Canadian with Indian heritage, Chew-Bose offers a sweetly candid portrait of the diasporic experience, and mingles it with a coming-of-age filmic quality in writing about moving out and living alone in New York City.

Now, as a lawful evil, I create markings on the books I own—with coloured pencils, according to a scheme I lay out on a card which I use as a bookmark while reading:

In reading Too Much and Not the Mood, this notation was necessary. I’m a huge fan of 1) language and 2) authorial presence or voice. I rarely care about what happens in a book. One of my favorite short story collections is “Nine Stories” by J.D. Salinger, which features nine stories about nothing in particular. My current favorite, “The Laughing Man”, is about a young member of the Comanche Club with a vested interest in their club leader, who has a mysterious girlfriend and likes to tell his boys an epic he made up called “The Laughing Man” in episodes as they ride the bus. That’s it.

The lemony beauty of Salinger’s storytelling has no interest in baroque plottiness or epic world-building. Instead, it relies on miniaturization, on gesture, on muted, silent intrigue passed between two opinionated strangers; in the awkward, heartfelt humanness of perfectly mundane moments that are illuminated in retrospect, in conjunction with vulnerable self-lecturing and musing. The magic does not lie in an exhilarating string of universally interesting events, but in the prism through which ordinariness is viewed, and made inexplicably valuable. It’s in the immeasurability of making a new friend, and, for some reason, loving them instantly.

This gesturely spirit is the spine of Too Much and Not the Mood— which is apt, because if the book’s focus was anything even slightly more measurable than a fleeting mood, it should have been called “Too Much and Not the Event”.

Chew-Bose’s eye is turned heavenward, reminding me I can use my mind as a snorkel while scrambling about in this absurd world. She has a gift for cataloguing feelings with hyper-precise language. I had to notate this book so I could flit through pages quickly, fumbling to burn onto my brain these generous and deliciously detailed instances of language to show myself how words can be used. I am grateful to this book for expanding my range of images.

Quotes:

Because writing is a grunt, and when it’s good, writing is body language. It’s a woman narrowing her eyes to express incredulity. It’s an elbow propped on the edge of a table when you’re wrapping up an argument, or to signify you’re just getting started. An elbow propped on the edge of a table is an adverb.

It’s imperative that writing consists of not living up to your own taste. Of leaving the world behind so you can hold fast to what’s strange inside; what’s unlit. A soreness. A neglected joy. The way forward is perhaps not maintaining a standard for accuracy but appraising what naturally heaps.

“Heart Museum” p.23

The dreamy, decidedly interior quality of the prose might not be for everyone. I know someone who cannot stand it, dismissing it as florid and overindulgent. I get that. Nonetheless, I love it, and will argue that this book has a purpose. To me, it’s a metaphor guidebook, vocabulary-mega-expander, and overall How-To on writing about specific things and making myself awake to all of the day’s miniature joys. And the slight gradience ever present between moods that can make all the difference.

Somewhat related recommendation:

“Lost in Translation” directed by Sofia Coppola. The great temptation of ennui is its romanticization. There’s a seductiveness about being down so that it motivates you to make good art. Or to crack your life with something magical. This film is gesturely and rivetingly ambiguous.

“Good Damage” Ep. 10, Season 6 of Bojack Horseman. Diane combats depression and struggles to write a memoir about her trauma, and laments her inability to make art out of her pain, reasoning that if she manages to make something out of the pain, it all would have been worth it.

0 notes

Text

On the nature of an aquarium

(As if letting mother know would diminish the status of daughter. Smooth-skinned daughter is decked with what was lacerated from mother, yet daughter lives in a mutilated way.)

A lagoon is a scar. The house filled with green water when the gloved hands untangled the noose fastened to the banister.

Alone now, Mother swims through the lagoon, her flesh against the walls, mourning, the way a string will hum though untouched in a quiet room.

She knows this. The dance of loss does not distinguish between pond and ocean and stream She lives it and knowing means little.

But then motherhood is not the lathery surface of the water but the crocodile that thrusts through it, more jaw than voice.

On Tuesdays Mother sits in an office, dripping. She does not look the doctor in the eye, does not answer his questions. With both hands she fishtail braids her hair, still wet from the sweat of birth.

0 notes

Text

Advertisement

After “Find Your Beach” by Zadie Smith

Take a slogan like find your oasis. Strange instruction. Oasis. An isolated, swollen hue of happy, never mind that the joy might be absent. Glee is a right, enforced with style. In this city I could hiccup and thoroughly exasperate the person walking behind me for delaying her oasis-finding for everyone wearing striped culottes in this goddamn place will stop at nothing to arrive at her oasis. There you have it. An odd proposition a mongrel of imperative and proprietorial form. A slogan that sifts my soul, gently threatening me to recalibrate. Is oasis still a noun or a state of mind.

In this city I knew a girl whose boredom was baroque. She waddled through cathedrals of indifference, penguin and eyelash away from the sun before a day spread wide open, grey to pure possibility, dogmatic limitlessness. But style is not sacred– naked in her oasis she thinks what next.

0 notes

Text

Beast

Of course the pig was there when the pond opened its eye. It had stood there for millennia unblinking, its heartbeat the weight of mushrooms. Flies danced on its pink skin, rubbing their faces with their fingers. Unchanging, the square of sky above the pig kept the still point of tenderness always missed by moments, the preferential treatment of the light in a permanent state.

Tribeless, quiet, and starving, those who passed the pond never recognized the beast, whose shadow cast water. Yet they warned of that valley, where the grass hissed at ankles; where low clouds murmured to the mountain something the color of blurring koi in the dark water.

Name another creature that is only ever its one body yet bodiless, ravaging the world by the billions. I drove a nail into my hand and the beast opened, soft as peeled fruit.

0 notes

Text

This Side

Pity is a cell and on this side of aching, fears are discreet, red ants travel quietly on the windowsill. Here, one learns to bargain with grief– a handful of life is just a fistful of blood.

The city blurs through the peephole: a dog snarls at a stranger, sweating pedestrians are a million fleshes yet none, the fur of a kitten makes mouth where the screeching tires chew it. The eye quivers.

Unhelped, the scenes are stacked hungers, dispossessed, having the impact of fragile things on a massive man-shaped world in the sex of violence.

In the cell, the staleness folds into itself: a golden heart, a knock on wood, a pair of restless eyes, an apostolic hope four walls that hold no center.

0 notes

Text

For Nostalgia

There is a light that footage cannot catch. The second before a photograph sets, the smile sneaks a breath, claiming its wish through shadowed teeth. Extending the enterprise of enshrining increases the reach of the image. Nothing exists in between which bridges the levels of moment and memory. It is the stride of the hand, knife-wielding, unthinkingly swift as it descends upon fig or finger.

a body prepared to cut but not to bleed.

0 notes

Text

Restaurant Review: Van Gogh is Bipolar

It would be best to think of this place as half restaurant, half art gallery.

To my absolute delight, Jetro, the owner, showed up as a sincere, eccentric guy whose home / restaurant doubles as his therapy and charity. I lunched there with my boyfriend and his cousin, and spent three hours just savouring the food and conversing at length with Jetro. He shared with us his "nightmarish" battles with mental illness and suicidality, and how a sporadic seed of desire to create a safe space for other people obliterated his destructive self-spiral nearly overnight. Since then he's been cultivating a community of various creatives to share their skills with one another as well as with the public through intimate workshops held in Van Gogh is Bipolar.

Besides staring expectantly at artworks and waiting for my emotions to bubble at their feet, my favorite part of visiting an art gallery is reading (or photographing, if it’s too long to read immediately) the wall text. I’m moderately obsessed with context. It’s cool to view an artwork, but it’s even cooler to know the artist behind it, so that this whole real world blossoms in the background of the artwork, deepening your range of appreciation for the artwork, solidifying a sense of friendship and community beyond the aesthetic achievements of the artwork. Or something. Which is why I loved Van Gogh is Bipolar. There’s something special about being given the opportunity to speak with the person behind the project. In hearing his story I had no choice but to open my heart—and stomach.

A chemist by education, Jetro carefully designed his diet to heal his mind without medication, and this diet is what you will be served at VGIB. The decor in the restaurant is stunning and endlessly novel, reflecting Jetro's remarkable travels around the world as well as his dynamic inner life.

Here’s what you will be getting for what I consider to be a relatively steep fee (their cheapest set meal is 999php per head):

1. Healthy, unique food.

Other reviews of VGIB will tell you that the menu is purposely ambiguous and that before receiving your meal, you will have virtually no clue of what you will be eating. You will be given a slip of paper on which you are to indicate the mood you want to achieve, and whether you are a vegan, pescatarian, or carnivore. I wrote that I wanted to be “happy” and indicated that I stuck to a “pescatarian diet”.

I received a seared salmon surrounded by a lush garden salad with apples, pinapples, mushrooms that resembled the mome raths in Alice in Wonderland, and various greens.

I've been thinking about the meal I had for days now. My body is sensitive and I regret nearly every meal I eat because I'll be left lethargic and totally drained. But the meal at VGIB felt PERFECT for me. Vegetables and fruits served there are grown in Jetro's family farm in Isabela, and are served raw and crisp. Everything on my plate was flavourful and a delight to eat. Jetro called it “living food” and those veggies felt alive.

2. A chance to contribute to Jetro's advocacy and charity initiative.

Homeless people are invited to eat there for free. The space is patently therapeutic for Jetro, his staff, and the diners. This transparent advocacy made me think hard about where my money was going whenever I ate out at other expensive places. Okay, to the food, yes, but where else? 3. An interactive and involving space.

I was apprehensive at first, because loudly decorative places often strike me as gimmicky or kitschy, overstuffed with eyejazz and strange thingies bunched together. VGIB wasn't like that because it all made sense when I met Jetro. It didn't feel fake or self-important; it was just the way some guy liked to arrange stuff in his house. He didn't draw attention to anything, either. Whenever he presented a space to us, it wasn't him trying to get us to admire anything, it was always in the context of us interacting with the space. He would gesture excitedly to a board— “you can write on this!"— and gesture to a rack of hats and quirky headwear, including a Mongolian warrior’s cap— "you can wear/move around/ have one of these!"

I would not recommend this place to someone who is 1) unsentimental, 2) just wants a simple meal, and / or 3) is not into having long conversations with strangers. VGIB is best contextualized as an extremely intimate and interactive art installation, because if you expect a contrived, commercialized "weird" restaurant, a lot of things might seem off-putting. All in all, I loved it. I'm not too sentimental myself, but Jetro's sincerity was hard to ignore and when we left I thanked him for his work. This space is a good idea run by a good person.

Van Gogh is Bipolar

Address: 154 Maginhawa, Diliman, Lungsod Quezon, Kalakhang Maynila

Phone: 0922 824 3051

0 notes

Text

Homeschoolers push for new Philippine educational approaches

Groups of families push for the ready integration of homeschooling and new learning approaches in Philippine educational policy.

Home education, or homeschooling, endorses the parents’ right to educate their children on their own terms. Distinct from home study, (which entails completing at home the workload dictated by a conventional school), homeschooling in the Philippines is largely a private enterprise, carrying affiliations with Christian church groups.

Most homeschoolers are registered under DepEd-recognized homeschool providers, which supply the families with curricula, and regulate the facilitation of the enrollees’ schooling.

The early 2010s, however, saw the steady rise of independent homeschoolers in the community. Sometimes called “unschoolers”, these homeschooling families proceeded without providers, customized curricula, and actively sought out co-curricular and extracurricular activities to supplement learning.

Homeschooling parent Nove Tan is leading a group of fellow unschoolers in their move to integrate their propositions into the sphere of Philippine educational policy, tentatively calling themselves the Philippine Homeschoolers Association (PHA), Philippine Association of Homeschool Families (PAHF), or Philippine Movement of Homeschool Families (PMHF).

“We need to make this movement to protect the next generation of homeschoolers. We are closely voicing out to our contact in Dep Ed for us to be heard. We need a solid union to represent the homeschool families - not providers. So this is focused on families,” said Tan.

According to Tan, the PHA has 3 goals: awareness, accreditation, and accessibility.

Tan, along with her colleagues, noted the importance of debunking myths on homeschooling, as they aim to empower Filipino families to consider taking a more deliberate approach to the education of their children.

They are pushing to be assessed directly by DepEd, instead of being recognized only by private homeschool providers. They are also looking to enjoin public schools to extend their accreditation to families who want to homeschool their children.

“Currently, most homeschooling families have to go through homeschool providers for accreditation and record-keeping. However, the fees charged by these providers are almost comparable to that charged by private schools, and in effect defeats the purpose for why most families opt for homeschooling: to provide quality education to their children at a lower cost,” said Tan.

In addition to this, the PHA is seeking curricular support, equal opportunities for DepEd-sponsored activities, academic support through public libraries and public sports facilities, and equal opportunities in college entrance examinations.

The University of the Philippines currently does not permit homeschoolers to apply for the UPCAT, and even homeschoolers recorded under official providers are required to collate various documents with the seal of conventional schools to verify the eligibility of the applicant.

Majority of the homeschool providers are sister institutions of conventional schools, so the providers are prompted to request authorization documents from their partners. The PHA is requesting the development of a specialized college application process for independent homeschoolers that will not require the intervention of a conventional school.

The Facebook group, Homeschoolers of the Philippines, currently has over 7,500 members. The number of independent homeschoolers is still undetermined, as unschooling is becoming increasingly popular, and homeschoolers under the Homeschool Global provider are opting out.

Apart from PHA, another group of independent homeschoolers is pressing to reinvent the dynamic of Philippine education.

School in A Backpack (SIAB) is led by Jana Estrevillo-Tupas and Owie Burns dela Cruz, homeschooling moms who envisioned an approach centered on experiential learning. School in a Backpack is a project that fosters a community of families inclined toward edu-travel (educational travel) and the concept of world-schooling (the world is the classroom).

Youtuber and chief marketing officer of SIAB Marga Manalo is looking to marketing the option of independent homeschooling to marginalized sectors, because of its low cost. She noted that while the Philippines has yet to fully embrace homeschooling, she said it would greatly benefit the poor, as well as the Indigenous Peoples, or IPs.

Addressing the issue of fading IP culture in the Philippines, Manalo proposed homeschooling among indigenous tribes as a solution. “I believe that your area is your school. Learning is always provided,” she said.

Emphasizing that SIAB is a project and not an institution, Dela Cruz dismissed its exclusivity to homeschoolers. A mixed group, SIAB is comprised of independent homeschoolers, and “after-schoolers” – multi-level students who attend conventional schools, and join in on edu-travel events during their free time. Nevertheless, the project was founded by Jana Tupas, who is an independent homeschooling parent.

“SIAB started out as a travel blog for one year, in December 2015. Jana Tupas is a traveller, and her son was enrolled in a conventional school. She felt that if she pulled her son out of school to travel, he would learn more from a week of travel than in a week of school. Then it grew from there,” said Dela Cruz, who helped Tupas organize School by the Shore, SIAB’s most successful event to date.

“Why learn marine life at home? Take them to the beach! Why teach them about waves using a textbook? Let them ride the waves, and let them read the waves,” added Dela Cruz.

The CHED memorandum policing field trips will not affect SIAB events. “SIAB is not a drop-off site for your children,” said Dela Cruz. “Hindi naman bawal mag-family vacation.[It’s not wrong for families to go on vacation.] We’re trying to champion practical parenting. We’re just a bunch of families travelling together, and learning along the way.”

SIAB is currently developing a more sophisticated membership system, which may incorporate the use of official member IDs. As of mid-2017, their Facebook page has almost a thousand members.

They are collaborating with IdeaSpace, app developers, and tourist guide agencies, in preparation for seminars and edu-travel events. An international branch, School in a Backpack California, is being patterned after the SIAB Manila framework.

Presently, the challenge meeting both SIAB and the PHA is the widespread misconception that homeschooling parents are not appropriately equipped to educate their own children. A public school teacher is qualified by a bachelor’s degree in Education, as well as by the licensure examination. Homeschooling parents working with an accredited provider need only present a college-level diploma.

When asked about the critiques she often receives from people who discover that she homeschools her children, Dela Cruz said, “Homeschoolers daw ay mga rebels na hindi marunong mag-socialize. [They say that homeschoolers are rebels who cannot socialize.] They also ask me, ‘What do your kids even learn from you?’ ‘Do you have a degree in teaching?’ People are under the impression that you must have a degree in education to educate your own child. Of course teachers in the conventional setting need to pass the licensure exams. Of course you need that if you’re teaching around 30 different children with different personalities- different learning styles, moods, cultural backgrounds- you’ll be handling 30 different human beings. But in homeschooling, you’re teaching a kid you raised yourself.”

Homeschooling moves around the concept of multiple intelligences, meaning that every child has a different set of strengths, and should receive a customized way of education.

“Homeschooling provides an option for people who want to break free from the system,” Dela Cruz continued- “That sounds so rebellious!” she laughed. “But yes, it serves all people. Everyone is different. It makes perfect sense to have different educational methods then. Everyone is different.”

0 notes

Text

Any animal is more elegant than this book: The Elegance of the Hedgehog

Unfortunately, this has to be the top contender for the worst “good” book I’ve read to date. So many words, so little substance– I’m shocked at how many words can be written about nothing much. I really wanted to like this book, guys, I really did. I liked Heidi Sopinka’s “The Dictionary of Animal Languages”, which has the same stylistic fragrance that Hedgehog attempts.

The difference?

The narrator of Languages brightened my world, while I was suffocated by the alternating narrators here, named Renee and Paloma.

Renee is a concierge approaching her sixties while Paloma is a twelve-year-old intellectual prodigy who loves writing in her journal and wrist-wringing over the constant trauma of living in, uh, a patently elite apartment complex in a gorgeous Paris neighbourhood where she is surrounded by relatively pleasant people and their pampered pets. Renee, who unflinchingly pronounces herself as stout and ugly, works in this apartment complex, and takes extreme precautions to ensure that the residents never find out that she is passionate about fine art, loves experimental cinema, and worships the literary canon. She also has a cat named Leo, after Leo Tolstoy, and is at all times paralysingly worried that the residents will get the reference.

First of all, the central premise is questionable and absurd in that it goes great lengths to cloyingly counterpreach the stigmatisation of something that may not even be a stigma. The book in 140 characters or less: a concierge affectedly and pompously demonstrates that it is okay for her to be intelligent. Here’s an excerpt:

“Concierges do not read The German Ideology; hence, they would certainly be incapable of quoting the eleventh thesis on Feuerbach. Moreover, a concierge who reads Marx must be contemplating subversion, must have sold her soul to the devil, the trade union. That she might simply be reading Marx to elevate her mind is so incongruous a conceit that no member of the bourgeoisie could ever entertain it.”

The problem with this is that I don’t think anyone in the apartment complex would care if they found out that Renee was intelligent. Renee takes up half her narrative time belabouring how difficult it is to be someone who betrays societal expectations by being a smart concierge. Not once is her delusional hypothesis put to the test. Not once was Renee allowed to wonder whether, in fact, people had something against smart concierges at all. If she were, this brittle plotline would disappear and invalidate the whole book.

Second, there are many characters living in the apartment complex, and I was interested in getting to know them. Colombe, Paloma’s older sister, was especially interesting! I did my best to piece together a portrait of her through Paloma’s exasperatingly condescending and hate-filled journal entries. I couldn’t help but feel that the fake-deep so-called “social commentary” was self-defeating and managed to destroy the storytelling. Where’s the due social commentary about hypocrites? You won’t find it in this book narrated by snobs devoid of self-reflexivity. What’s worse is that the musings of Renee and Paloma are less sincere social commentary than snooty flexings of how brutally they can tear down other people. The other characters are ruthlessly flattened and it’s a shame, because I don’t know if this is entirely necessary. The narrators sentimentally and self-importantly capitalise the words “beauty”, “art”, and “humanity” but their intellectual posturing is soulless and regrettably anti-humanity and unbeautiful. They’re so deep in their heads that they’re not ruminating on the human condition at all— they use other people as sandpaper against which to sharpen their mean verbal acrobatics. This is so blatantly their point and I rolled my eyes when Renee called herself a prophet for contemporary times or whatever. What’s the point of endlessly contemplating beauty and art when you spend hours and hours overarticulating how other people are worthless? I was not impressed by their devotion to jasmine tea and camellias. Reading about mean people is fun when the whole thing is graced with irony, when the author is so fully in on it. But the narrative voices of Paloma and Renee are so strikingly identical that I can’t help but feel that the author, Muriel Barbery, is writing with minimum effort, writing so close to her own heart that there isn’t much space for self-irony or self-parody. I could be wrong though. I also took note of how Japan was depicted in this book— all hype, no depth. This contrasts with how Paloma conflates Asia with poverty in talking about a Thai boy adopted by a French family:

“And now here he is in France, at Angelina’s, suddenly immersed in a different culture without any time to adjust, with a social position that has changed in every way: from Asia to Europe, from poverty to wealth.”

I know she’s 12, but it struck me. Japan in this book is fetishised and immediately valued exclusively because of a handful of its cultural exports. Sushi, bonzai, haiku, Ozu, the traditional bow, and wabi-sabi are briefly mentioned. That’s all. What’s afforded is the Google-able iconography. The book goes no deeper, and the peppering of Japanese references did nothing to re-posture the characters, which is what it seemed to be going for. Kakuro, the Japanese man introduced to change the narrator’s lives, was so thinly written. Extras in KDramas have received richer characterization. I was baffled as to why he, poised ummistakably as the pivotal character, was paper-thin and dimensionless, when the other characters were described with such precision albeit disdainfully. He “changes their lives” because the plot said so. One last thing: this book was published in 2009, before discourse on mental health became more widespread. Words such as “anorexic”, “autistic”, and “retarded” are used a couple of times as adjectives, usually in derogatory contexts, which will date the book.

Man. I really wanted to like it.

Somewhat related recommendations:

“Pure Heroines”, an essay included in Jia Tolentino’s bestselling collection “Trick Mirror”. The essay explores the tropes performed by female literary characters, i.e. as children, they’re exceedingly crafty and prematurely disillusioned by their environment, and the plot hinges on how gloriously they can rewire themselves to escape it all; as teens, like Paloma, they’re angsty and hot and intellectual; and as grown women, they become casualties of certain institutions, such as religion, marriage, or what have you, and eventually kill themselves. Paloma, in this case, is a suicidal teenager. Interesting.

“The Dictionary of Animal Languages” by Heidi Sopinka. Also set in Paris. Also about an art-loving woman. Language is also somewhat florid but oftentimes delectable. Is a plotty book but doesn’t read as plotty, because it’s configured so diaristically. A sweet-smelling collection of painterly phrases.

0 notes

Text

Death of Kitt

Today is Sunday, October 13. Kitt died last Tuesday, October 8. (It’s strange I got the urge to transcribe this entry now, technically November 8, as it is 12:42 AM. The one-month mark since Kitt’s passing.) Five days ago.

1.

When I have a wound inside my mouth, I like to run my tongue over it, teasing the pain, keeping my body alive to it; same thing with a hangnail. The pain is surprising each time, failing to make my body’s acquaintance.

Mama was standing in the bathroom, holding Kitt in Papa’s red towel. We had pulled her out of the attack by the dogs. I was panicking (I stop writing here to pick at a small pimple on my left cheek). “She’s dead,” Mama said, looking down at Kitt’s face. “Her eyes are different.”

I play that scene in my head repeatedly. I pause at random times in the day and find myself sitting. But I can’t remember much anymore about what that felt like. When you push the same poles of a magnet together, they resist, and so my mind resists when I search for the emotional sparks and remnants of that specific moment. But my mind resists and I flicker with a slight tingle between my eyebrows. I’ve thought about this a lot.

After Mama told me that she was dead, I stood there for a few seconds and the first thought I remember having was, “I can cry now,” and I did. Mama rubbed my back and I cried over Kitt and my mind was empty.

2.

I’m surprised it took this long for me to write about it, but this is simply how long it took. And that’s reminiscent of something Jenny Odell wrote about—how we render reality has a direct effect on what is possible at any given time. And what is possible probably happens. I take these things to mean that what is articulated—even privately— directs what happens. What I notice and pay attention to and render via articulation determines what happens and most importantly, the way I remember what happened. And when Kitt died I had no thoughts. Now I’m searching and searching for thoughts, handlebars for that memory, and I know that I did think “that is my Kitty” and I felt wrong. I lit up with feeling, but then it was a grey non-feeling. Whatever it was, something happened.

3.

What it was: an accidental unplugging of the TV mid-movie, the brutal burp of the surge extinguished, the reverse supernova of the pictures being there then immediately not, the static tickle in the middle of the screen, a slicing confirmation of the mortality of images. That’s what it was and I didn’t think of words. My mind was unplugged for a split second and there was my kitten, my fragile thing and her perfect fur that smelled like fresh blankets. Her eyes were blank. The perversity of it all filled me wordlessly. Her death was wordless as it was bloodless, by no means anything more eloquent than a miserable emptying out.

0 notes