Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Fashion designer Rachel Washington is a creative entrepreneur who also teaches at College for Creative Studies and works as a cutter for a Michigan clothing line. She is our guest artist for Mint’s new workshop Business Basics for Young Creatives this Saturday.

Mint asked Washington, who owns So Raw Creative, one big lesson every young creative must learn. She wrote:

“One big business lesson I want young creatives to learn is how BIG the business part of the creative business is. A lot of people think that being a creative business owner is fun and easy because all you have to do is make stuff and people will buy it.

“Actually running the business can take ALL of your time if you let it.“

Hear more from Rachel Washington Saturday afternoon. The interactive workshop aimed at young creatives ages 14 to 21 is organized by Pamela Hilliard Owens, a Mint board member and owner of three creative / communications businesses. Register by 9 a.m. Saturday on EventBrite. The Mint workshop will be held on Wayne State University’s campus.

© Vickie Elmer 2017

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday FAQ: What do you like about making costumes? What are some challenges you run into?

I enjoy making costumes because a lot of times it forces me to think about things differently. In recreating something and trying to do it accurately I’ve found out new techniques for doing things like sewing on patches or constructing a garment. Instead of just doing what I know to make things work, I have to figure out the proper way to do them to make my costume accurate or work correctly. It’s challenging to figure exactly how to put costumes together that you don��t physically have to re-create. If I was remaking a costume that I had I could look at construction details like stitches, pattern pieces, etc. However, if I’m making a costume that I’ve only seen pictures of then there’s a lot of research that need to be done. I use YouTube videos, articles, images, whatever I can find about the costume to try to re-create it as best as possible.

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Mildred Blount

Text from: Mildred Blount: “Milliner to the Stars!” and designer of hats for “Gone With The Wind”

By Jill Morena

Much behind-the-scenes work on Gone With The Wind and the people who performed that work continues to remain largely unknown outside the production sites of the 1939 film. The story of an African American milliner was recently brought to my attention through an email query—had I heard about the woman who designed Scarlett O’Hara’s hats? A link to a video on YouTube, telling the story of Mildred Blount—“Milliner to the Stars!”—was included in the message. I was intrigued and wanted to learn more.

John Frederics, a New York–based milliner (who later changed his professional name to John P. John, and is perhaps better known through the company, Mr. John, Inc.), was the creative side of the partnership of the company John-Fredericks. Frederics had always been credited with making Scarlett O’Hara’s hats, although he received no onscreen credit. Mildred Blount, who had been making headgear since childhood and continued honing her skills as a young woman working in various shops in New York City, applied for a job with John–Fredericks and got the position.

An article on Blount in Ebony magazine in 1946 described the scenario: “It took courage for her to ring the bell at John Frederics in answer to their ad for a learner, for this was the royalty of America’s hatters. They were taken aback. No Negro had ever applied before. Yes, she assured them she had talent. All she asked was a chance. P.S.—She got the job.” The article continues: “Her exhibit of hat miniatures at the N.Y. World’s Fair attracted the attention of Mrs. David Selznick, and ultimately landed John Frederics the pot-of-gold assignment of the day—milliners to the tremendous cast of Gone With The Wind. Mildred did most of the work, although the credit line went to her employers.” This begged the question, who really made the hats for Scarlett O’Hara? John Frederics or Mildred Blount?

Negotiations between Selznick and John Frederics began hurriedly in January 1939 and were fraught and arduous. Found in the Selznick collection are many memos and telegrams discussing the terms desired by Frederics and Selznick’s commitment to keep the arrangement to SIP’s (Selznick International Pictures) economic advantage. Selznick was adamant about refusing screen credit for John Frederics, Inc., and Frederics was concerned with being compensated fairly for his time and reaping publicity benefits. After much back-and-forth between SIP and Frederics—and a lucrative commercial tie-in deal for SIP with a manufacturer, recommended by Frederics, to make commercial copies of the hats—a contract was agreed upon and signed on January 13, 1939.

John Frederics had pointed out the impossibility of executing hats “satisfactorily, especially when the picture is in color, 3,000 miles away.” A train compartment was swiftly booked for John Frederics to travel to Los Angeles, and he arrived at SIP set on January 20. Frederics optimistically estimated that he could finish 15 hats in two or three days; he stayed in Los Angeles for nearly a month. By the end of his 26-day stay, he had completed 12 hats, including the curtain dress hat (“Scarlett #13”). He was brought back (following another contentious negotiation) in April to make 10 more hats for Scarlett and other characters, including Melanie Wilkes and Belle Watling.

While it cannot be accurate that Irene Selznick saw Blount’s miniature hats at the World’s Fair that spring or summer and recommended John Frederics to Selznick (as he was already considered for the job in December 1938), it is very likely that Mildred Blount created Scarlett’s hats for the “Honeymoon” sequences in New York. Frederics was unable to complete his work on Scarlett’s hats during his second trip to Los Angeles in April–May 1939 and agreed to make the remainder of the hats at his New York studio.

In addition, Blount very likely had a hand in choosing materials and working with Frederics on the designs for the first round of Scarlett’s hats in New York. In one memo, Frederics asks that sketches and fabric swatches be sent to New York in advance of his January trip to Los Angeles so that he could purchase or choose the bulk of the materials in New York, which he preferred to the Los Angeles market. Between January 13 when the contract was signed and January 19 when he arrived in Los Angeles, Frederics had to work at lightning speed to get his materials and design ideas in order, and it’s very unlikely he did this alone.

As the production history of Gone With The Wind makes clear, the concept of the lone genius working in isolation, be it producer, designer, or director, is a myth. The talents of many people working on the production often did not receive recognition in print. However, Blount’s design legacy shows that she remains anything but anonymous. Her talents and reputation continued to soar while creating for John Frederics, Inc.. She left John Frederics, Inc. and founded her own eponymous label in Los Angeles by the mid-1940s, designing for Hollywood actresses as well as private clients, including Gloria Vanderbilt and Marian Anderson. She continued to work until her death in 1974. Her hats can be found in the collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the California African American Museum.

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Dapper Dan

Text from Sneaker Freaker From his eponymous store on E 125th in Harlem, Dapper Dan (real name Daniel Day) presided over a remarkable fashion emporium in the 80s and 90s. His uptown clientele was a heady mix of hustlers, street cats and hip hop royalty, all of whom shared a mutual love of what Dap himself called a ‘macho type of ethnic ghetto clothing’. That’s Harlem shorthand for streetified-luxury, a glorious melange of status symbols such as mink, ostrich, crocodile and python married with his own trademark ‘reappropriatons’ of Louis Vuitton, Gucci and Fendi yardage.

LL Cool J, Big Daddy Kane, Salt ‘n’ Pepa, Run DMC, Fat Boys and Public Enemy publicly repped Dapper Dan hard and his fame quickly spread beyond the local hood. Peep Eric B and Rakim’s Follow the Leader and Paid in Full for classic Dapper Dan outfits in full effect. Mike Tyson famously punched out opponent Mitch Green in front of the store whilst on his way to pick up the classic ‘Don’t Believe the Hype’ jacket. The place became notorious.

Jackets, bags, hats, two-tone jumpsuits with all-over prints – there was nothing Dapper Dan wouldn’t cover in acres of hand-printed and embossed leather. Gucci seat covers, LV-inspired upholstery and a famous convertible lid for Rakim’s Jeep showed Dap’s talent for entreprenurial diversification. Another iconic ensemble was a Louis Vuitton jacket with huge gold Mercedes badges. Less well known were the sneakers that matched his jackets, but shoes were definitely on the menu at Dapper Dan’s. The Fat Boys for example repped Nike Air Force 1s with Gucci Swooshes on the cover of their long player Crushin’. Nearly everything was a one-off designed for an individual, making Dapper Dan one of the OG customisers.

As his fame and fortune grew, the European fashion houses swooped. Infuriated by the very public knock-off of their trademarks and inflamed by their utter rejection of black, urban culture, they took legal action against Dap and he went underground. There’s tons more to learn about Dapper Dan, take a look at these: Dapper Dan Blog

Complex Dapper Dan Gallery

NY Magazine: Harlem Legend Dapper Dan on the Power of Logos

0 notes

Text

Ona Judge Staines: She Challenged George Washington and Won Her Freedom

The following text from : http://www.theroot.com/ona-judge-staines-she-challenged-george-washington-and-1790854513

Written by Steven J. Niven

A plaque depicting Ona Judge Staines on the wall of the President’s House in Philadelphia Courtesy of lwf.4pha.com

On May 24, 1796, a runaway-slave advertisement was posted in the Pennsylvania Gazette by the steward at George Washington’s house in Philadelphia. It read:

Absconded from the household of the President of the United States, ONEY JUDGE, a light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy hair. She is of middle stature, slender, and delicately formed, about 20 years of age. She has many changes of good clothes, of all sorts, but they are not sufficiently recollected to be described—As there was no suspicion of her going off, nor no provocation to do so, it is not easy to conjecture whither she has gone, or fully, what her design is; but as she may attempt to escape by water, all masters of vessels are cautioned against admitting her into them, although it is probable she will attempt to pass for a free woman, and has, it is said, wherewithal to pay her passage. Ten dollars will be paid to any person who will bring her home, if taken in the city, or on board any vessel in the harbour;—and a reasonable additional sum if apprehended at, and brought from a greater distance, and in proportion to the distance.

Oney, as she was known to George and Martha Washington, was one of nine enslaved African Americans who served in the President’s House in Philadelphia from 1790 to 1796. Judge was the only slave who escaped from the Philadelphia Executive Mansion, although Hercules, the president’s famed chef, made an even more daring escape on Feb. 22, 1797, the president’s 65th birthday, from the Washington plantation at Mount Vernon, Va. There is no record of Hercules after his escape, but a fairly strong paper trail enables us to piece together the fate of Ona Judge, in part because of the Washingtons’ strenuous, but ultimately unsuccessful, efforts to reclaim her.

A Taste of Freedom in Philadelphia

Ona Maria Judge was born around 1774 at Mount Vernon. Her mother, Betty, was recognized as the finest seamstress on the plantation and was a “dower slave,” technically still owned by the estate of Martha Washington’s first husband, Daniel Peake Custis. Ona’s father was an English indentured servant who had worked at Mount Vernon.

Since a slave’s status followed the mother’s line, Ona was born enslaved, as was her older half brother, Austin, who had a different father and would later serve Washington as a stable hand at the Philadelphia President’s House. From an early age, Ona would have performed whatever domestic labors were required of her at Mount Vernon. By the age of 10, she began attending Martha Washington. Her main work involved sewing and making clothes; Gen. Washington praised her as a “perfect mistress of the needle.”

George Washington was elected the first president of the United States in 1789, and in 1790, when the capital moved to Philadelphia, Ona traveled with the family to their official residence. She served as the main personal attendant to the first lady, and her tasks would have included dressing and powdering her mistress, accompanying her to official receptions and other public and social duties, and being ready, at all times, to meet Martha Washington’s needs. It was important to the first family, too, that Ona was herself always seen to be impeccably well-groomed and clothed in public.

Ona, Austin and Hercules were allowed to attend a circus, the theater and other public events on their own. They also interacted with Philadelphia’s increasingly assertive free black community, which had grown from only 240 in 1780 to 1,849 in 1790 and would exceed 6,000 by 1800. She had arrived in Philadelphia just as the Free African Society and the first independent black churches were being established, and it is likely that she was inspired by the example of Absalom Jones, Richard Allen and other African-American founders. In addition, white refugees from the Haitian revolution were given refuge in the city after 1793, many of them bringing their slaves. By 1796, over 450 Haitians had claimed their freedom under a Pennsylvania state law that enabled them to do so after a full six months’ residency.

Ona Judge Plots Her Escape

The Washington slaves knew that the president had taken precautions to prevent them from taking advantage of this law. His plan was to send them back to Virginia before they completed six months’ residence, then return them to the Philadelphia for another period of service. Washington informed his secretary about this scheme, stating his “wish to have it accomplished under pretext that may deceive both them [the slaves] and the Public.” One historian has suggested this was “perhaps the only documented incident of George Washington telling a lie.” The primary reason for this subterfuge was financial: Ona and all but two of the Mount Vernon slaves in Philadelphia were Custis dower slaves. If they gained their freedom under this law, Washington not only would lose their labor but also would have to personally reimburse the Custis estate for their loss under his supervision.

In the spring of 1796, Washington entered the final year of his second term in office, and the staff were informed they would be returning to Mount Vernon for good that summer. The first lady, now in her mid-60s, also told Ona Judge around this time that she was to be bequeathed to a Custis family granddaughter back in Virginia, a prospect Judge dreaded, since she despised her intended new owner. Realizing that the relative freedom she had enjoyed in Philadelphia would soon become a memory, Judge carefully planned her escape.

As she recalled 50 years later, the entire household was preparing to leave for Virginia, and so it was not seen as suspicious when she began packing the “many changes of good clothes, of all sorts” mentioned in the runaway ad. Assisted by acquaintances in Philadelphia’s free black community, she stored her belongings at a friend’s house and found a merchant sloop, the Nancy, that would transport her to Portsmouth, N.H. Judge made her way to the Nancy one evening in late May while the first family was at dinner. By the time they learned of her escape, Judge had arrived in Portsmouth. She was not legally free and was at risk of recapture under the federal Fugitive Slave Law—which Washington had signed in 1793—but for the first time in her life, she was free of the demands of Martha Washington.

The First Family’s Desperate Search

The Washingtons were shocked, and the Gazette advertisement suggests that they initially had no idea why she had fled. Martha Washington, in particular, took Judge’s flight badly, viewing it as ingratitude and as a personal slight, and came to believe that Judge was pregnant and had been seduced by a mentally unstable Frenchman. At least, that is the story that George Washington used in his efforts behind the scenes to recapture her. Certainly there were many Frenchmen and French- and Kreyòl-speaking Haitians in Philadelphia, but there is no evidence that Judge had relations with any of them.

In late August, however, Judge’s luck ran out. The daughter of Sen. John Langdon, a close friend of the Washingtons and a frequent visitor to the Executive Mansion, came upon her on a Portsmouth street and expressed surprise that she was not attending the first lady. President Washington was soon apprised of the situation and immediately ordered Oliver Wolcott, the secretary of the treasury, to engage the Portsmouth collector of customs to retrieve her.

That action was illegal by the terms of Washington’s own Fugitive Slave Law, which required a slaveholder to use the federal courts. Washington was aware, though, that a public attempt to openly return a possibly pregnant slave to bondage would be bad publicity and might even provoke a riot. The Portsmouth collector initially agreed to comply with the request from his commander in chief, who warned him to act cautiously so as not to alarm Judge’s alleged French seducer. Judge herself, in Washington’s view, was “simple and inoffensive.”

But the collector came to quite a different conclusion about her motives once he interviewed her. She convinced him that there was no seducer, French or otherwise, and that a “thirst for compleat freedom” had been her only motivation. He reported that Judge, though, might be amenable to returning to Mount Vernon if the Washingtons promised to emancipate her upon Martha Washington’s death.

George Washington was livid, replying that, “To enter into such a compromise with her, as she suggested to you, is totally inadmissible,” since it would reward her unfaithfulness and set a bad example to his other “more deserving” slaves. The president also continued to insist on his story of a French seducer, although he may have finally abandoned that idea when informed of Judge’s plans to marry a local free black sailor, John Staines. The couple married in January 1797 and had a daughter a year later.

Finally Free

Until recently, most Washington biographers believed that at this point George Washington abandoned his efforts to regain Judge. Perhaps the president had given up hope, but his wife had not. In July 1799, Martha Washington made one more attempt to kidnap Judge through a family member who traveled to Portsmouth, but the plot was thwarted when Sen. Langdon heard of it. Langdon was appalled and warned Judge, who managed to find refuge with another free black family several miles away in the town of Greenland.

Following Gen. Washington’s death at the end of 1799, and Martha Washington’s three years later, Ona Judge Staines was finally able to enjoy her freedom—although she and her children remained fugitive slaves according to the law. She worked for a while as a house servant and had three children with John Staines: Eliza, William and Nancy. Judge Staines was widowed in 1803, and 17 years later her son, William, left for sea, never to return. Her daughters died in the early 1830s, and Judge Staines lived her final years in Greenland as a pauper.

Brief interviews by abolitionists in 1845 and 1846, when she was in her 70s, provide the only direct record of her thoughts and actions. She stated that she had received no formal education or religious training while enslaved and criticized the Washingtons for not properly observing the Sabbath. Asked if she regretted leaving the relative comforts she had enjoyed for a life of poverty, Ona Judge Staines insisted that she had made the right choice, having learned to read and write in freedom, and having been made a “child of God” by that means.

On Feb. 25, 2008, 160 years after her death, Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter declared the first “Oney Judge Day.” Since 2010, her defiance of the president and the first lady and her remarkable escape can be explored at the historic site located on the grounds where the President’s House—and his slave quarters—once stood.

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Art Smith

Arthur Smith was born to Jamaican parents in Cuba in 1917. His family settled in Brooklyn in 1920 and Smith showed artistic talent at an early age, winning honorable mention as an eighth grader in a poster contest held by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Encouraged to apply to art school, he received a scholarship to Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

There he was one of only a handful of black students, and his advisors tried to steer him towards architecture, suggesting he might readily find a job in the civil sector of that profession. His lack of proclivity for mathematics eventually forced him to abandon this path, however, and he turned to commercial art and a major in sculpture, training that would prove invaluable.

After graduating in 1940, Smith worked first with the National Youth Administration and later for Junior Achievement, an organization devoted to helping teenagers find employment. He also took a night course in jewelry making at New York University. That and the friendship with Winifred Mason, a black jewelry designer who became his mentor, set him on the course of his adult artistic life. Mason had a small jewelry studio and store in Greenwich Village, and Smith became her full time assistant. He subsequently moved from Brooklyn to the Village’s Bank Street. In 1946 Smith opened his own studio and shop on Cornelia Street in the village with the financial assistance of a near-stranger who wished to undermine Mason because of bad feelings over business transactions.

Cornelia Street was an “Italian block” then, and Smith suffered racial violence from some of his neighbors. His store-front windows were smashed on one occasion and he was made to feel dangerously unwanted. Soon after, he moved to 140 West Fourth Street just 1/2 block from Washington Square park, the heart of Greenwich Village where as an openly gay black artist he felt more at home

The new store was better located business-wise and socially, and Smith’s career began to take off. In addition to selling from this new location, he started to sell his wares to craft stores in Boston, San Francisco, and Chicago, and by the mid-1950’s he had business relationships with Bloomingdale’s and Milton Heffing in Manhattan, James Boutique in Houston, L’Unique in Minneapolis, and Black Tulip in Dallas.

An important early influence on Smith’s career was Tally Beatty, a young black dancer and choreographer. Beatty introduced Smith to the dance world “salon” of Frank and Dorcas Neal, where he became acquainted with some of the city’s leading black artists including writer James Baldwin, composer and pianist Billy Strayhorn, singers Lena Horne and Harry Belfonte, actor Brock Peters, and expressionist painter Charles Sebree. Through Beatty, Smith also began to design jewelry for several avant-garde black dance companies, including, in addition to Beatty’s own, those of Pearl Primus and Claude Marchant. These commissions encouraged him to design on a grander scale than he might otherwise have done, and the theatricality of many of his larger pieces may well reflect this experience.

In the early 1950’s Smith received feature pictorial coverage in both Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and was also mentioned in The New Yorker shopper’s guide, “On the Avenue.” For many years thereafter he ran a small advertisement in the back of The New Yorker. By the 1960’s he had begun to use silver more readily in his jewelry, and as his client base increased so did his custom designs. He received a prestigious commission from the Peekskill, New York, chapter of the National Association for Advancement of Colored People, for example, to design a brooch for Eleanor Roosevelt, and he made cufflinks for Duke Ellington that incorporated the first notes of Ellington’s famous 1930 song “Mood Indigo.”

In 1969 he was honored with a one-man exhibition at New York’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Art and Design), and in 1970 he was included in Objects: USA, a large traveling exhibition organized by Lee Nordness, an influential early dealer in craft objects. After his death 3 major exhibits were organized celebrating his work; "Authur Smith A Jeweler's Retrospective" at the Jamacia Arts Center in Queens NY, 1990, "Sculpture to Wear; Art Smith and his Contemporaries", at the Gansevoort Gallery, NYC, 1998, and "From the Village to Vogue" at the Brooklyn Museum., 2008. Small catalogues from the 2 museum shows are available. The definitive collection and exhibit of all the artist jewelers of Art Smith's generation is beautifully illustrated and discussed in "Messengers on Modernism American Studio Jewelry 1940-1960", written by Toni Greenbaum published by Flammarion and the Montreal Museum in 1996. Smith had had a heart attack in the 1960s, and by the late 1970s his health had declined. The shop on West Fourth was closed in 1979 and Art Smith died in 1982.

excerpted from the Brooklyn Museum's FROM THE VILLAGE TO VOGUE: THE MODERNIST JEWELRY OF ART SMITH show catalogue

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: B Michael America

B Michael America - Runway - Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Fall 2015 NEW YORK, NY - FEBRUARY 18: Phylicia Rashad, designer B Michael and Condola Rashad walk the runway at the B Michael America fashion show during Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Fall at New York Public Library on February 18, 2015 in New York City.

(Photo by Jemal Countess/Getty Images for Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week)

Fashion designer B Michael was born and raised in Durham, Connecticut. His mother was a real estate agent and his father, a certified public accountant. B Michael found early design inspirations in his mother’s creativity and keen sense of style. He attended the University of Connecticut and also studied at the New York Fashion Institute of Technology.

B Michael was first hired as an account executive for a Wall Street firm, but decided to pursue a career as a millinery designer. He started designing hats under Oscar de la Renta, Louis Feraud, and Nolan Miller for the 1980s television soap opera Dynasty. Following his success on the show, B Michael became creative director for the Aldo Hat Corporation. In 1989, he decided to launch his namesake millinery line and in 1999 developed and launched his first couture collection with the help of PR Guru Eleanor Lambert.

B Michael’s collections have garnered appreciative fans including socialites and personalities such as Cicely Tyson, Ashley Bouder, Amy Fine Collins, Tamara Tunie, Beyoncé, Nancy Wilson, Susan Fales-Hill, President Barack Obama's poet laureate Elizabeth Alexander, and Lena Horne, among many others. He also designed Whitney Houston’s costumes for the motion picture, Sparkle. He has shown his b michael AMERICA Couture collection in Beijing, China, Korea and Shanghai, and his ready to wear fashion line b michael AMERICA RED sells in Macy’s department stores across the United States.

In 1998, B Michael was granted membership in the prestigious Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA). He has served as a guest lecturer at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology. He also serves on the advisory boards of Dream Yard Project, YAGP (Youth America Grand Prix) and the Cicely Tyson School of Performing and Fine Arts. In addition to his work and community activism, B Michael is an avid collector of vintage books, artifacts and photography.

B Michael lives in New York City with is life partner Mark-Anthony Edwards and has two daughters, Saferra and Mychal.

Visit the designers official website

View the latest b michael collection shown Sunday, February 12th, 2017 at 3pm

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Ann Lowe

Article: Why Jackie Kennedy’s Wedding Dress Designer was Fashion’s ‘Best Kept Secret’

By Raquel Laneri

October 16, 2016

In 1953, when Ann Lowe received a commission to create a wedding gown for society swan Jacqueline Bouvier, she was thrilled. Lowe, an African-American designer who was a favorite of the society set, had been hired to dress the woman of the hour, the entire bridal party and Jackie’s mother. But 10 days before Jackie and Sen. John F. Kennedy were to say “I do,” a water pipe broke and flooded Lowe’s Madison Avenue studio, destroying 10 of the 15 frocks, including the bride’s elaborate dress, which had taken two months to make.

In between her tears, Lowe, then 55, ordered more ivory French taffeta and candy-pink silk faille, and corralled her seamstresses to work all day. Jackie’s dress, with its classic portrait neckline and bouffant skirt embellished with wax flowers, went on to become one of the most iconic wedding gowns in history, but, decades later, Lowe would die broke and unknown at age 82.

Now, the country’s first black high-fashion designer is finally getting her due. Three Lowe gowns are on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s new National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, DC. On Dec. 6, 2015 the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in Manhattan will display several Ann Lowe gowns in an exhibition on black fashion. And there are two children’s books about the designer in the pipeline.

“She was exceptional; her work really moves you,” says Smithsonian curator Elaine Nichols.

Lowe was born in Clayton, Ala., in 1898. Her grandmother was an enslaved dressmaker who stitched frocks for her white owners and opened her own business after the Civil War. Little Ann learned to sew from both her grandmother and her mother. Even at age 6 it was clear that she was quite talented.

“She would gather the scraps from her mother’s workroom and go to the garden and create these beautiful fabric flowers,” says Elizabeth Way, a curatorial assistant at the Museum at FIT, which has three Lowe dresses in its collection.

Through the 1940s to the end of the ’60s, Lowe was known as society’s “best-kept secret.”

When she was 16, Lowe took over the family business after her mother died and left an unfinished order of gowns for the governor’s wife that needed to be finished. Around this time, Lowe also married an older man named Lee Cohen and gave birth to a son, Arthur, but the union was short-lived. About a year into the marriage, the wife of a Tampa business tycoon invited her to come to Florida and create dresses for her and her daughters. Lowe jumped at the opportunity.

“It was a chance to make all the lovely gowns I’d always dreamed of,” Lowe told the Saturday Evening Post in 1964. “I picked up my baby and got on that Tampa train.” Cohen, who disapproved of her ambition, sent her divorce papers.

Lowe, however, wanted to be more than a dressmaker. In 1917, at the age of 18, she took a sabbatical from her job in Tampa to enroll in a couture course in New York City. When she arrived, the head of the school was aghast that he had admitted a black woman, and he tried to turn her away. Her white classmates refused to sit in the same room as her, but she plugged away and graduated early.

Ten years later, Lowe moved to New York for good with $20,000 she had saved working in Florida and settled in Harlem with her son. She started taking jobs as an in-house seamstress at department stores like Saks Fifth Avenue and for made-to-measure clothiers like Hattie Carnegie. It didn’t take long for word of this young, talented artist to spread.

Through the 1940s to the end of the ’60s, Lowe was known as society’s “best-kept secret,” designing outfits for famous socialites like the Rockefellers and du Ponts and Hollywood stars like Olivia de Havilland. When Christian Dior first beheld her handiwork, he exclaimed, with probably a bit of envy, “Who made this gown?”

“She had excellent technique,” says costume historian Margaret Powell, who is working on one of the kids’ books about Lowe. “Even the insides [of her dresses] are beautifully finished . . . Her clients realized that they could get the same quality as Dior at a much lower price.”

In 1950, two customers persuaded her to open her own salon, and her white business partners helped her snag a space on tony Madison Avenue. “It was difficult for a black woman at that time,” says Powell.

Unfortunately, Lowe’s business sense did not match her design acumen. She charged clients barely enough to break even, and her commission for the Kennedy wedding nearly bankrupted her.

“She bought more fabric, hired people overtime and just swallowed all the lost money [after the accident],” says author Deborah Blumenthal, who is writing another children’s book about Lowe.

Plus, Lowe was already unknowingly giving the family a bargain, charging just $500 for Jackie’s ensemble, compared with the $1,500 the dress likely would have cost from a competitor. She ended up incurring a loss of $2,200. “She never told Jackie or her family . . . It’s just heartbreaking,” Blumenthal says.

Worse, when Lowe took an overnight train to Newport, RI, to hand-deliver the dresses herself, the guards at the wedding venue told her she had to use the service door because of the color of her skin.

“She said, ‘If I have to use the backdoor, they’re not going to have the gowns!’ ” says Blumenthal. “They let her in.”

For a period of time in the 1950s, her son, Arthur, managed her books, and he helped rein in his mother’s lavish spending and keep the company afloat. But in 1958, he was killed in an auto accident, and she was frequently broke once again.

In 1962, Lowe was in a bad spot. She had closed her salon due to outstanding costs, taken a job as an in-house dressmaker at Saks, quit that, lost her eye to glaucoma — an operation she couldn’t afford and which the doctor provided gratis — and owed $12,800 in back taxes. But then she got a call from the IRS saying an “anonymous friend” had taken care of her costs. Lowe told both the Saturday Evening Post and Ebony that she believed it was Jackie, who Lowe had remained close with.

“[She] was so sweet,” Lowe told the Saturday Evening Post in 1964. “She would talk with me about anything.”

That generous gift allowed Lowe to reopen her business, and it was soon bustling. In a typical six-month period she and her three to five pattern-cutters and seamstresses would complete 35 debutante gowns and nine wedding dresses. But she was still bleeding money, and losing her eyesight, to boot. “I’ve had to work by feel,” she told the Saturday Evening Post. “But people tell me I’ve done better feeling than others do seeing.”

Around this time, Ann Bellah Copeland commissioned Lowe to create a dress for her wedding to Gerret van Sweringen Copeland, the son of Lammot du Pont Copeland.

“Her assistants hovered around her to be certain that she got it all right,” Copeland, now in her 70s, wrote in an e-mail to The Post. “No one made dresses as beautifully.”

Lowe retired in 1969, at age 71, and moved to Queens to be with her so-called “adopted daughter” Ruth Alexander — who had helped Lowe at her shop for years.

“She lived a very quiet, serious life. But everyone says that she was very sweet, very patient. Around her family she could be a funny person. And she was very determined,” says Powell. “She showed that an African-American could be a major fashion designer. She made it to that highest level. She’s an inspiration.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Black Designer Profile: Ola Hudson

Text from Clutch Magazine The late, and simply fabulous, Ola Hudson remained relatively unknown to the wider public but the brilliant designer and bona fide creative received mad respect from the pop entertainment circuit & the community of genuine creativity.

The fierce artiste was born Ola Oliver in 1946. As a young adult her vibrant energy manifested itself through dance. Mrs. Hudson studied with the Lester Horton School of Modern Dance and with Bella Lewitzsky and Linda Gold in Los Angeles. Her talent and ambition landed her in the prestigious Institute of Dance in Paris, Switzerland’s Le Loft, and The Max Rivers School in London. It was here where she settled down for a spell, marrying fellow free-spirit Anthony Hudson. Hudson was one of the lucky ones. During a time when album covers were true works of art, his was displayed on many including that of Joni Mitchell, David Bowie & Neil Young. In July of 1965, the pair welcomed their first child into the world. They named him Saul Hudson, the rest of the world calls him Slash.

Not much is publicized about Ola’s return to LA, but all signs point to a turbulent marriage to her alcohol addicted spouse and a desire to embark on a career as a costume designer. She left Saul with his father in the UK for a time as she established her career in Hollywood, but the family reunited in the City of Angels about a year after her return. Mrs. Hudson wasted no time in making a name for herself as a premiere costumier to the stars. Her lengthy clientele list included Diana Ross, Ringo Starr, John Lennon, the Pointer Sisters, Stevie Wonder, Janet Jackson and David Bowie. As a matter of fact, Ola Hudson designed the suits worn by Bowie in the 1976 film, The Man Who Fell To Earth plus a collection of her work designed for the British pop star is on permanent display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art. On an amusing tip, the two dated for a time, which resulted in a young Slash catching ole Ziggy and his mom in a compromising position on one occasion. Mrs. Hudson was a major player in the industry, designing fashion collections for Henri Bendels in New York, Fred Segals and Max Field Blu in Los Angeles, Right Bank Clothing in Beverly Hills, Neiman Marcus and was the creator of Skitzo, an authentic boutique situated on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip.

In 1972, The Hudson’s welcomed a second son into the world, Albion. The pair raised their boys in the “neo-hippie environs” of Laurel Canyon.Although Ola & Anthony’s marriage endured, it was filled with periods of separation, which naturally had an impact on their two boys. She always insisted that despite it all, their unit was a loving one. On her eldest, Slash, she told Rolling Stones, “He was drawing from the time he could pick up a pencil,” adding that he was weaned on her Led Zeppelin albums and raised in a very loving household. “I’ve been shocked at a lot of things I’ve read where it sounds like I left him on somebody’s doorstep in a basket. They make it seem as if he never had a family and grew up on the streets like an urchin, but that’s not true. It’s just part of his image. He’s not all leather and tattoos.”

Ola’s mother was also influential in providing an amorous space for her boys and has been credited for Slash’s success by nurturing his creative energy and providing the future rocker with first guitar. It’s reported that Ola did her best to balance the demands family and show biz life. She allegedly made several attempts to include her sons in her creative and social endeavors where they rubbed shoulders with a number of industry artists.

Her authentic inventiveness was unrelenting – as if art and existence were one in the same. In her later years Ola continued to perform original poetry, song & dance and honed her skills as a visual designer and photographer. Her most recent work titled I Stand, was published in Voices Magazine, as well as a piece called Testimony – inspired by the tragedy in New Orleans. Her photography has been featured in Fred Segal, West Hollywood. Mrs. Hudson was a dedicated member of the Board of Directors at Westside Regional Center for the Handicapped. And recently, was nominated by Santa Monica College as a Distinguished Alumni for Creative Consultation, Choreography and Costume Design for the College.*

After a long battle with cancer, Mrs. Hudson passed in 2009 at the age of 62. A life cut too short, it was inspiring, bold, fabulous and full of adventure. Speaking of his mom, Slash once said, “She turned me onto all different forms of art and the importance of artistic self-expression and creative communication thru music and dance from as early on as I can remember.”

0 notes

Text

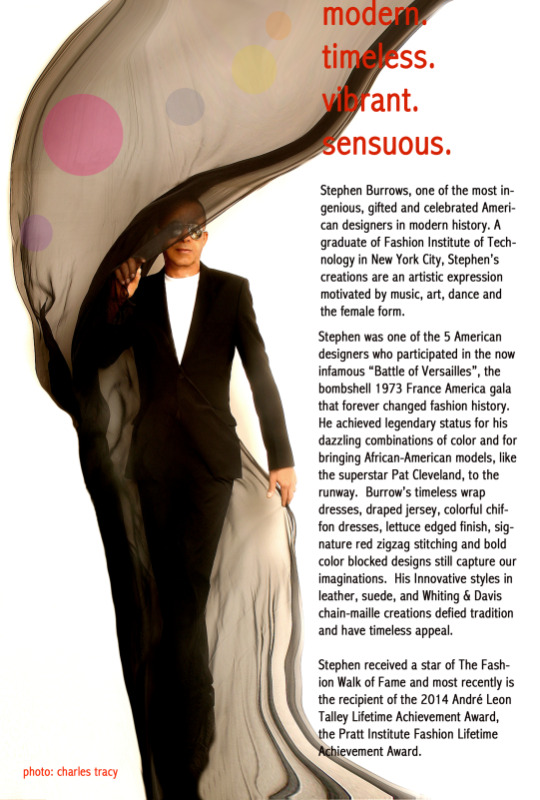

Black Designer Profile: Stephen Burrows

from Stephen Burrow’s website

Stephen Burrows Looks Back as Retrospective Bows

The designer did not seem to be the least bit wistful, frazzled or reflective about being surrounded by his past.

The following text is copied from WWD

By Rosemary Feitelberg

Stephen Burrows made sure that The Supremes’ “Up The Ladder to the Roof” will be piped into the retrospective of his work that bows Thursday night at the Museum of the City of New York.

Aside from it being a favorite song he liked to blast, it could double as an anthem for his career. Fittingly, the exhibition is called “Stephen Burrows: When Fashion Danced.” And dance he did, regardless if it was to Motown, rhythm and blues, New York sound or rock ’n’ roll. The music, like the up-until-dawn club scene he was once part of, has fueled his creativity as much as the buzz and street life he finds so stimulating about New York City.

This story first appeared in the March 20, 2013 issue of WWD. Subscribe Today.

As 25 helpers scrambled about on Tuesday afternoon pinning muslins, rolling on photographs like wallpaper and setting display text, Burrows did not seem to be the least bit wistful, frazzled or reflective about being surrounded by his past. (Never mind that he has spent the better part of the last six weeks helping to track down and select 50 pieces for the show.) Other flashbacks could be heard loud and clear in a documentary about the 1973 “Battle of Versailles” between French and American designers, of which Burrows was one. “It’s humbling to have so much attention. Usually something like this doesn’t happen until you pass,” he said. “Being successful is being happy in what you’re doing and being able to make money at something that you love to do. I can’t imagine anything that makes you happier than finding true love.”

Born in Newark to divorced parents, Burrows has always thought of himself as “bicoastal” in that he always traveled between his mother’s New Jersey home and his father’s Harlem one. After graduating from the Fashion Institute of Technology, his senior co-op job at the missy blouse company Weber Originals turned into a full-time one. “I was making $125 a week. That was a fortune back then,” he said.

By 1968, he had ventured out on his own thanks to private clients like the Brazilian artist Jim Valkus, Bobby Breslau and Roz Rubenstein. In 1970, his Fire Island friend Joel Schumacher — a Henri Bendel-er before he hit Hollywood — suggested he meet with the store’s then-president Geraldine Stutz and a 12-year alliance was formed. Hardworking as he was, Burrows ran with a fast crowd, including Pat Cleveland, Alva Chinn, Halston, Joe Eula and Elsa Peretti. After an after-dinner nap, Burrows would get up around 11 to hit the clubs with his friends — The Loft, Sanctuary and others. At 3 or 4 a.m., they would head home for a few hours sleep before going to work. Burrows said, “We didn’t really talk about fashion unless to tell someone we loved what they were wearing that they had made. It was mostly about dancing and the nightlife. Music was a big force.”

Alcohol and drugs were other forces too, though Burrows didn’t go into detail about those aspects of the period. “We were a product of the times. All that stuff was around, available and taken into account when needed,” he said.

Standing in the Target-sponsored Commune section of his retrospective, which plays up his disco-era rainbow-colored designs, Burrows said he is partial to the early days. The show opens with a colorful photo of Grace Jones snarling opposite a black-and-white one of a bespectacled Burrows wearing a Jell-O printed shirt. Eyeing an image of his first photo shoot in Central Park in 1970, Burrows said the Seventies were all about freedom of expression. That same year he became the first African-American designer to win a Coty Award. “It didn’t matter who you were with as long as you were happy,” he said. Gesturing towards framed sketches and vibrant knitwear, Burrows said, “I’ve always had a thing for phallic symbols. It’s kind of a signature.”

Others know him for joining Halston, Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta and Anne Klein in the “Battle of Versailles,” the legendary fashion showdown with Yves Saint Laurent, Christian Dior, Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Cardin and Emanuel Ungaro. “It was such a proud moment for American fashion,” Burrows said. “Of course, when we did it, we didn’t think about it that way.”

He recalled sitting beside Blass in first class as they flew to Paris for the show. “We didn’t know about the party the models were having in the back of the plane,” said Burrows. Nor did they know the figurative drawings Eula had spent hours sketching in New York would not fit to scale Versailles’ vaulted ceilings. “The Eiffel Tower he drew looked miniscule,” Burrows said. “The room dwarfed the scenery. We had to use a bare empty stage. The situation, we thought, was kind of hopeless. But it turned out to be such a knockout.”

Meeting Josephine Baker — “divine in a catsuit looking like she was naked” — and Saint Laurent were Versailles snapshots he will never forget. “Saint Laurent came up to me and said, ‘You make beautiful clothes,’” Burrows said. “He was sitting in the next booth at the event. The designers weren’t allowed to be with the clothes during the show.”

As for the current designer scene, Burrows rattled off Rick Owens, Lanvin and Jean Paul Gaultier as three favorites. Less enthusiastic about younger designers, he said, “I don’t understand what’s happening with fashion today. It looks very added-to, like everything in the kitchen sink. But that’s just me.”

Celebrity designers don’t hold his interest either. “They come up and just die. There are all these celebrity lines and in 200 days they’re gone. Meanwhile, someone else who does design can’t get going,” Burrows said. “The word ‘designer’ is so loosely used today. Of course, I don’t know what the cure for it is. It’s an animal in its own right.”

Asked about the lack of non-Caucasian models on many designer runways, Burrows said, “I find it peculiar, because part of their customers are not Caucasian. I don’t know that it will ever change. I always use and will always use all different girls.”

Minority designers also still struggle to get financing. “It’s particularly difficult for the minority designers. I don’t know why that is. I find it curious. It’s something that minorities will always be facing.”

At its most profitable in 2006, Burrows’ label was a $2 million business, but there have been fits and starts along the way. After running his own company from 1970 to 1982, he shuttered the doors and bowed out of the limelight. Caring for his cancer-stricken father and brother consumed most of his time, though he continued to create clothes for private clients and design costumes for the off-Broadway show “Momma I Want to Sing.” In 2001, Henri Bendel convinced him to come out of retirement and the following year he set up his own studio on 134th Street to relaunch his label. By 2008, he subletted space on West 37th Street — a few blocks from where his grandmothers first met as sample hands for Hattie Carnegie in the Twenties.

In August, Burrows had to deal with the blow of losing his business partner of 15 years, John Robert Miller, who died unexpectedly. Now he and the brand manager Mary Gleason are speaking with potential investors and hope to have new financing in place for a spring 2014 collection. Occasionally he designs for private clients “but not so much because I hate sewing,” Burrows said. “I’ve never had the patience for sewing. It’s terrible — I can’t sew a straight line.”

As for how he sees his role in the fashion world, he said, “The essence of Stephen Burrows — be happy when you’re in the clothes and have fun with what you’re wearing. I’m very simplistic about things like that. That’s just how I am.”

youtube

#African American Fashion#Fashion Designer#History of Fashion#Black History Month#Long Red#Black Fashion

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: LaQuan Smith

LaQuan Smith was born in Queens, New York on August 30, 1988. An only child, Smith spent his early years instructed by his grandmother who instilled a passion and skill for sewing and pattern making. Smith cultivated this craft throughout his teenage years and by 2007, the 19-year-old wonder kid started his fashion career in earnest. To that end, he apprenticed simultaneously with Blackbook Magazine and famed stylist, Elizabeth Sulcer. For an aspiring designer, the experience was a seminal one solidifying Smith’s penchant for strong, sexy, separates. He applied this aesthetic to his first capsule collection a selection of gilded separates and accessories. His distinctive work sparked interest among fashion icons and risk takers including Rihanna and Lady Gaga, both of whom were early supporters of the gifted designer.

Smith’s work also intrigued Vogue Magazine, whose Editor at Large, Andre Leon Talley selected Smith as his mentee. Harnessing the momentum of these experiences Smith formally debuted his first collection in the Spring of 2010. Held at the Society of Illustrators Upper East Side headquarters in New York City, the event attracted the industry’s elite.

On the runway, celebrities like Serena Williams modeled in the designer’s collections while off the runway, Diane Von Furstenberg and Vogue’s Alexandra Kotur amongst others watched on. It was an auspicious start for Smith’s eponymous label.

Since its formal debut in 2010 the brand has gained acclaim for its endless archive of distinctive garments and details which have been often imitated by established and emerging design houses.

Chief among these are the Gilded Stocking, popularized by Lady Gaga and Rhianna and the Nova Poodle Skirt made famous by Ariana Grande.

Smith’s signature style has found a devoted following amongst Hollywood AListers such a Beyonce, Jennifer Lopez and Kim Kardashian each of whom have selected the brand on and off the red carpet. In addition to his robust celebrity clientele, Smith has cultivated an equally dynamic private order clientele which spans the globe from Lagos to London. Smith’s singular aesthetic has also been tapped by world recognized brands including Heineken and Chicago’s famed Joffrey Ballet, all of whom have commissioned custom editions of Smith’s designs.

LaQuan Smith, and his eponymous label, are headquartered in Queens, New York and deliver globally.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Telfar Clemens

directly from the Telfar PRESS KIT For the past eight years Telfar Clemens has been one of New York’s most consistently forward thinking and exciting young designers. Born in New York and raised in Liberia, his line carves a completely unique territory in the fashion landscape by defining a brand which is neither conceptual nor accessible — but both in extremis. This paradox is nowhere more evident than in TELFAR’s design philosophy of simplexity™. Simply put TELFAR is Extremely Normal™. At once highly conceptual and obsessively practical; minimalist and irreverent; countercultural and mainstream; edgy and coyly practical — the line flouts convention by flaunting conventionality. With both feet in the 21st century, the TELFAR consumer is young, urban, plugged in through every orifice and extremely discerning. As other brands struggle with online strategies TELFAR has boldly innovated: showing collections through viral mock-reality videos, using a crowdsourcing app to let fans help design a collection and collaborating with the most relevant young artists and musicians, some of the worlds most established and reputable brands and the hottest press both online and in print.

ARTIST COLLABORATIONS

Working at the interstices of art and fashion TELFAR has nurtured ongoing collaborations with a number of emergent and established artists and musicians. Foremost among them is Guggenheim Artist of the Year Ryan Trecartin, who produced Telfar’s much acclaimed S/S 2013 video FORMALE;LIFE.

TELFAR also sat for a series of portraits Trecartin produced for the first annual W Magazine Art Issue and is featured in his feature length film The Encyclopedic Palace which debuted this summer at the Venice Biennale. TELFAR has also engaged with artist Lizzie Fitch for a number of sculptural pieces including the SHOPMOBILE easily collapsible shop-onwheels on which he has shown two collections, featuring a modular construction and 3d printed hands and feet cast from the designers own body. In addition to this TELFAR has worked over the years with renowned musicians such as Fatima Al Qadiri, DJ’s such as Shayne Oliver (HBA) and Venus X as well as groups such as Art Collective cum online magazine DIS and the art collective cum lifestyle brand; SHANZHAI BIENNIAL.

For his A/W 2012 collection TELFAR produced a customized line in collaboration with Opening Ceremony for sale globally in store and online. For TELFAR’s Spring/Summer and Autumn/Winter 2011 collections the designer collaborated with Doc Marten boots to create two custom shoe designs. For S/S11’s FORmale collection TELFAR produced a sling back boot with elastic back strap, followed by the layered leather, fleece lined boot for A/W11’s Extreme Layers collection. For TELFAR’s collection entitled Extreme Lengths A/W 2010, the designer collaborated with Converse on footwear for the active individual in extreme conditions, with a winter collecion of athletic shoes that were layered and employed the insulation of patchwork. In his Summer 2008 collection, TELFAR also collaborated with Converse to create the “mandal”, eliminating all plastic from the Converse Classic All-star to effectively create a Summer sandal from within the iconic shoe.

TELFAR has also collaborated with FILA, Reebok, and he continues an ongoing collaboration with American Apparel on his conceptual cotton-based diffusion line, UN.DER T.

Telfar spring/summer 2014 looks. (Image from Vice)

View last season’s show on Vogue’s website

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Travis Hamilton

Fashion Designer Travis Hamilton, Founder of Negris LeBrum Clothing Company, started his company in 2003 taking inspiration from the love between a beautiful French Creole woman, Negris, and a handsome man, Sam LeBrum that overcame all societal differences and brought them together. This company aims at presenting this story of amazingly strong and pure love by the means of fashion.

Starting from the campus of College, the popular fashion brand Negris LeBrum, Houston (U.S), has surely come a long way, as they ready themselves to launch their fifth collection at New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2016. Debuting at New York Fashion Week Fall 2012, Negris LeBrum has taken constant incremental steps and has shown a tremendous growth and popularity. With such growth and popularity come increasing expectations of a better-than-previous show.

Reportedly, for this Spring/Summer collection, the “Lenoir collection” presents the looks, colors, designs and styles that are retro classic. This collection’s inspiration is the aspirations, attitude and strength of the Negris woman. With their designs and dresses, they intend to represent these traits of a modern woman, a woman who is loved by many, admired by all and perceives elegance. A fusion of these with a fashionable freedom inspires Negris LeBrum designs.

Since its inception, Negris LeBrum has grown significantly as a brand and has become vastly popular. With every new line of clothing introduced, they just better themselves. Travis Hamilton has been presenting fresh and unique collections through a great show every time. With his previous shows and constantly increasing popularity, the expectations for his next show at New York Fashion Week are higher than ever and so is the cost required to do so. View the Negris LeBrum Fall 2017 Show Sunday, February 12, 2012 at 7pm

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Tracy Reese

Text from Tracy Reese’s official website With an innate desire to create beautiful things, Detroit native Tracy Reese headed for Manhattan in 1982 to attend Parsons School of Design where she received an accelerated degree in 1984. Upon graduation, Reese apprenticed under designer Martine Sitbon while working for the small contemporary firm, Arlequin. Reese has also worked at the some of the industry’s top fashion houses, including Perry Ellis where she was the design director for Women’s Portfolio.

In 1997, Tracy Reese launched her eponymous collection to rave reviews. By combining bold hues and prints with modern silhouettes and shapes, Tracy Reese creates fresh designs perfect for the confident, sophisticated woman.

Tracy Reese designs have been featured in the top fashion publications - Vogue, Elle, Glamour, InStyle, O, the Oprah Magazine, Essence and WWD. Her distinct point of view has also made her a celebrity favorite. Notable fans of the brand include First Lady Michelle Obama, Sarah Jessica Parker and Taylor Swift.

Her secondary line, plenty by Tracy Reese, was introduced in 1998. Plenty embodies the modern bohemian spirit, offering a distinctive combination of joyful color palettes and playful details. plenty by Tracy Reese is all about versatile everyday essentials with effortlessly, sexy styling. Launched in Spring 2014, plenty DRESSES by Tracy Reese captures the needs of the contemporary dress consumer who is seeking fashion which takes her from work to a special occasion. Color, vivid prints and feminine styles have instantly made this brand a stand out. Tracy Reese, plenty by Tracy Reese, and plenty DRESSES by Tracy Reese are sold nationwide in top department stores and specialty boutiques as well as retailers throughout Europe & Asia.

A member of the Council of Fashion Designers of America since 1990, Tracy Reese serves on its Board of Directors. Tracy is a champion for many charities and social causes. She is an advocate for HIV/AIDS charities and has served on the AIDS Fund Committee for the New York Community Trust for five years. She is also part of the Turnaround Arts program through the President’s Committee of the Humanities and Arts and is the Turnaround Artist for Barnum School in Bridgeport, CT.

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Carly Cushnie of Cushnie et Ochs

Text via UrbanBushBabes

Carly Cushnie was born and raised in London, after graduating high school attended Parsons School of Design in both Paris and New York, where she completed a BA in Fashion design. While attending Parsons Cushnie was hired as a design intern at Donna Karan, where she developed a strong sense of drape and movement, later she joined the team as a design intern at Proenza Scholar. In her graduating year Carly completed an internship at Oscar De La Renta where she worked closely on the ready to wear collection.

After completing a military high school education, Michelle Ochs raised in Maryland headed to New York to begin her studies at Parsons School of Design where she completed a BA in Fashion Design. During her time at Parsons she was hired as a design intern at Marc Jacobs, then joined the team as a design intern at Isaac Mizrahi Made to Order. In her final year at school Michelle interned at Chado Ralph Rucci.

While attending Parsons, Carly and Michelle collectively received top honors at school that included the CFDA scholarship and the SAGA award, as well as runner-up and winner of 2007 Parsons Designer of the Year. Carly’s and Michelle’s senior collections were also featured in a cover story for WWD upon graduation.

Carly’s international sophistication and Michelle’s American sensibility, informs the brands intricate draping and precise tailoring. The diverse backgrounds coupled with a strong sense of the female form and thorough education resulted in a collection that is an intricate play of shape and technical craftsmanship. It is a constant evolution of form and function that is CUSHNIE ET OCHS.

Since the launch of CUSHNIE ET OCHS with their Spring 2009 collection, they have received the 2009 Ecco Domani Fashion Foundation Award and were finalists for the 2010 Fashion Group International Rising Star Award. CUSHNIE ET OCHS is sold in the most exclusive boutiques worldwide and has been featured in Vogue and W magazine as the New Guard as well as has numerous credits in leading publications. Watch their fashion show LIVE Today at 3PM!

Read More:

Empowering Women Through Wearable Art, with Cushnie et Ochs

The Cut’s Backstage Interview With Cushnie et Ochs (Sept. 2012)

The Fashion Spot’s 21 Questions with… the Designers of Cushnie et Ochs

0 notes

Text

Black Designer Profile: Jeffrey Banks

Jeffrey Banks is an acclaimed Menswear Designer whose signature American design style has significantly impacted the entire fashion world. The Jeffrey Banks Signature Menswear Collection was launched in 1977, consisting of tailored clothing, dress furnishings and sportswear. It established a new benchmark for men of style.

The American art of casual dressing was reinvented when Banks took over as Design Director of Merona Sport in the 1980's. He introduced never before seen colors and fabrications coupled with soft styling and loose fit for men, women and children. Merona Sport became an instant hit and sales rocketed from $7,000,000 to $85,000,000.

Throughout the last decade Banks has been Creative Design Director for several highly successful private label Menswear lines. They include the East Island and the Metropolitan View lines for the Bloomingdale's chain which have generated over $70,000,000 in sales.

Banks was selected to be Design Director for the historical launch of the first brand extension for Johnnie Walker Scotch. The Johnnie Walker Collection includes casual sportswear and timepieces. The collection has changed the perception of Johnnie Walker, helping to make it more appropriate for today's younger affluent male.

Presently, Hart Schaffner Marx (HSM), Watson Brothers and Platinum Hosiery have Jeffrey Banks licensing agreements. HSM produces a collection of fine tailored clothing for the US specialty and department store market. Watson Brothers manufactures neckwear and belts for both the US and Canadian specialty and department store markets. Platinum Hosiery knits the hosiery collections for the US market.

Throughout his distinguished career Banks has been honored for his talent and creativity. He has won two Coty Awards for Outstanding Menswear and Men's Furs. He received the Cutty Sark U.S. Menswear Designer of the Year Award for his Extraordinary Contribution to Men's Fashion, an Earnie Award for Boyswear and the Pratt Award for Design Excellence.

While obtaining a degree in Fashion Design at Pratt Institute and Parsons School of Design in New York City, Jeffrey Banks was Design Assistant to both Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein.

0 notes

Text

The Story of Elizabeth Keckley, Former-Slave-Turned-Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker

A talented seamstress and savvy businesswoman, she catered to Washington's socialites

Text from Smithsonian.com

By Emily Spivack

Elizabeth Keckley was born into slavery in 1818 in Virginia. Although she encountered one hardship after another, with sheer determination, a network of supporters and valuable dressmaking skills, she eventually bought her freedom from her St. Louis owners for $1,200. She made her way to Washington, D.C. in 1860 to establish her own dressmaking business and met first lady Mary Todd Lincoln.

Just after Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, in 1861, the FLOTUS hired Keckley (also spelled Keckly) as her personal modiste. Keckley took on the role of dressmaker, personal dresser and confidante, and the two women formed a special bond. Mary T. and Lizzy K., a new play written and directed by Tazewell Thompson, explores their relationship.

Much has been researched, written and analyzed about Keckley’s life as a result of the unusual friendship. In 1868, Keckley published a detailed account of her life in the autobiography Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House. A thorough study of her dressmaking legacy is still being uncovered, though, explained Elizabeth Way, a former Smithsonian researcher and New York University costume studies graduate student who worked for the Smithsonian last summer researching Keckley.

Prompted by Mary T. and Lizzy K., which runs through May 5, 2013, at the Mead Center for American Theater at Arena Stage in Washington, Threaded spoke with Way about Keckley’s dressmaking handiwork.

Are Elizabeth Keckley designs plentiful today?

Not that many still exist actually. And even with those pieces that do exist, there’s a question as to whether they can be attributed to Keckley. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History has a Mary Lincoln gown, a purple velvet dress with two bodices, that the first lady wore during the second presidential inauguration. There’s a buffalo plaid green and white day dress with a cape at the Chicago History Museum. At the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Illinois, you’ll find a black silk dress with a strawberry motif that you’d wear to a strawberry party, which was a 19th-century Midwestern picnic tradition, but it’s disputed as to whether or not it’s a Keckley. Penn State has a quilt that Keckley made from dress fabrics, and other items are floating around in collections. For example, Howard University has a pincushion with her name on it.

Elizabeth Keckley

You mentioned it’s difficult to attribute clothes to Keckley. Why is that?

At the time, no labels or tags were used. And because fabric was so expensive, dresses were often taken apart and reconstructed as a completely different dress using the same material. She made clothes for many official women in Washington, so one way to determine a Keckley dress is if any of those women kept a journal and noted that kind of detail within it.

I assume she followed fashion conventions of the mid- to late 19th century, but did she have a specific style?

Her style was very pared down and sophisticated, which a lot of people don’t imagine when they think of the Victorian era. Her designs tended to be very streamlined. Not a lot of lace or ribbon. A very clean design.

How did she build such a thriving business as an African-American woman in the mid-1800s?

She was very skilled at building a client network, which was very notable considering she was a black woman and previously enslaved. She consistently made friends with the right people and got them to help her, which was not only a testament to those people, but also to her. She had incredible business savvy.

Would she sew the entire dress?

When she started out, she would do the complete dress, sew it up, add the trim, everything. As she became more successful, she was able to hire seamstresses to do some of the sewing and she trained people to help with the construction. Generally, she would work on the fit of the dresses.

Mary Lincoln’s purple velvet skirt and daytime bodice are believed to have been made by African-American dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley. The first lady wore the gown during the Washington winter social season in 1861–62. National Museum of American History.

Was Mary Lincoln wearing only Keckley while she was the first lady?

Mary Lincoln liked to shop. She would go to New York to shop at the department stores, which were just emerging at that time. You could buy ribbon and trim and anything unfitted, like a cape. It was just the beginning of mass production. But any kind of dress had to be made by a dressmaker because the fit was so specific that it had to be customized. Mary Lincoln was said to order 15, 16 dresses each season, which took about three months to make.

While Mary Lincoln was known, and criticized, for an overly youthful style that embraced bright colors and floral patterns, the dresses made for her by Keckley that have survived are the opposite of that style—Keckley really designed with very clean lines.

Striped and floral Mary Lincoln dress, attributed to Keckley, significantly altered from original design. Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Where did Mary Lincoln, or other women for that matter, find out about fashion trends?

Fashion at this time copied France line for line. Whatever was happening at the French court was what women in D.C. wanted.

Elizabeth Keckley was an incredible businesswoman and was also known for her beauty.

In her memoir, she recalls that people thought she was beautiful. The Washington Bee, the African American newspaper, treated her like a black socialite within the African-American community. She dressed well—she was not gaudy or showy, but more pared down and refined. She was known for being elegant, upright and appropriate—the Victorian ideal.

How did that Victorian approach play into Keckley’s designs?

The Victorian ideals permeated all levels of American culture and determined what it meant to be an appropriate woman no matter who you were. There were so many social rules about what you had to wear in the daytime and nighttime, and Keckley’s garments all followed those rules, especially for Mary Lincoln, who was in the public eye so frequently.

How long would it take for Keckley to make one dress?

I’m not exactly sure. Maybe two, three weeks. To drape the fabric, cut the fabric, use a sewing machine on some parts and hand-stitch others. Also, remember—she was making multiple dresses at a time, and by the time she was a successful dressmaker in Washington, she also had seamstresses working with her.

What was Keckley most known for amongst women in Washington who wanted a dress from her?

Her fit and her adeptness when it came to draping fabric on the body. She was known to be the dressmaker in D.C. because her garments had extraordinary fit.

What were the dressmaking tools she would have been using at the time?

A rudimentary sewing machine, which is at the Chicago History Museum, pins, needles. She may have measured with inches but because that system was so new, she could have used another marking system for measurement. And she may have used a drafting system that came out in the 1820s for patternmaking.

How much was Keckley earning at the time when she was making dresses for Mary Lincoln?

When Keckley first moved to D.C. and worked as a seamstress for a dressmaker, she made $2.50 a day.

She recalls in her memoir that when she became a dressmaker, she made a dress for Anna Mason Lee who was attending a reception with the Prince of Wales in 1860, which was a very high society event in D.C. Captain Lee gave Keckley $100 to purchase lace and trim for his wife’s dress. So while that doesn’t quite speak to how much she was earning, it does put things in perspective and speak to the level of cost and the timeline of moving from a seamstress to a dressmaker. In fact, when she bought the trim from Harper Mitchell, the trim store, for Lee’s dress, the shop gave her a $25 commission for the purchase. That $25 was already ten times what she was making as a seamstress when she first came to Washington. Working as a dressmaker was the highest-paying opportunity women had during that time period, and Keckley’s dresses were known to be very expensive, the envy of women in Washington.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Read more on the Smithsonian website

0 notes