Text

Changes in Attitude toward Work and Workers’ Identity in Korea

Changes in Attitude toward Work and Workers’ Identity in Korea

Park Gil-Sung and Andrew Eungi Kim

Abstract

The age-graded seniority system, familial structure, and lifetime employment, at least as an ideology, used to be the hallmarks of Korean corporate culture. Following the financial crisis in 1997, however, layoffs, early retirement, job insecurity, and increased competition have become the realities of the workplace. The question is: how have these uncertainties and the harsher corporate environment changed the way Koreans think about work?; how has their work ethic changed? This paper explores how Koreans’ perception of work has become more realistic and self-centered, as they are much more conscious of their future potential and working conditions. Their sense of identity is no longer primarily based on work and jobs. Not surprisingly, job satisfaction has conspicuously declined. What is also noteworthy is how the heartless world of work has inspired changes in job selection considerations. What all of this shows is that Korean workers’ identities are no longer homogeneous and work-oriented. Following the financial crisis, working conditions and types of employment have become much more varied, leading to the gradual diminution of collective consciousness.

Keywords: work ethic, identity, financial crisis, Korean workers, job mentality

Introduction

In September 2001, South Korea (henceforth Korea) paid the last US$140 million installment to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), completing the repayment of IMF loans three years ahead of schedule. The loan may have been paid in full, but the so-called “IMF crisis” not only halted the nation’s phenomenal decades-long economic growth but also brought about fundamental changes in lifestyle, employment pattern, corporate culture, and worldview (Kim 2004; Park 2004). Indeed, the most striking aspect of the impact of the financial crisis is that it has not been limited to the economic sphere, as virtually every sector of Korean society has undergone and, to a large extent, is still undergoing significant changes. The crisis has meant not only a comprehensive restructuring process at the institutional level but also a halt to the Korean way of thinking and behaviour at the individual level. In post-financial crisis Korean society, moreover, there seems to be a sense of urgency to do away with traditional values and practices that hamper efficiency and competitiveness.

Although much has been written about the financial crisis, especially on the causes of the crisis, its economic consequences, and preventive measures hinging upon institutional change, only scant attention has been paid to the impact of the financial crisis at the level of everyday life, noticeably the formations of a new work ethic and social identity. Of all the sectors that were impacted by the financial crisis, it is the world of work that underwent one of the most significant changes. In fact, the financial crisis is the critical juncture from when work as Koreans knew it fundamentally and irreversibly changed. This came about largely because of IMF conditions for its bailout loans, which included a demand that called for a more flexible labor market. The demand for greater labor flexibility eventually led to an amendment of labor law that opened ways for layoffs, hitherto illegal. Needless to say, the elimination of the proverbial lifetime employment and the legalization of layoffs brought about significant changes in employment patterns. In addition to outright layoffs, companies have used early retirement and honorary retirement schemes to scale down their pay rolls. As a result, the starting retirement age of Korean workers is found to be about 10 years younger than that of the member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Jang (2003) shows that the age at which more workers lose their wage labourer status than those who gain such status is 35 years, while the average age at which the same process happens among the workers of OECD countries is 45 years. He also shows that Korean workers in their early thirties have only about a 60% chance of still being employed by the time they turn 50 years old. What all of this means, of course, is that retirements and layoffs begin much sooner for Korean workers than their counterparts in other OECD countries.

Despite all these changes that brought about greater uncertainty in the job market, Korea has maintained an impressive unemployment rate that has hovered below 4.0% since early 2000. The unemployment rate may have dropped to an impressive level, but it has been achieved through a conspicuous proliferation of various forms of nonstandard employment, including temporary workers, short term contract workers, contingent workers, temporary help agency workers and daily hires. The increase in irregular forms of employment became more pronounced since the financial crisis, happening for the first time since labour statistics have been compiled. This trend has continued unabated since then, e.g., nonstandard workers comprised 51.6% of the total labor force in Korea in 2002. This rate is actually the highest among the member countries of the OECD. For comparison, the figure for Spain in 2000 was 32%, followed by 27% for Australia, 13% for Germany, and 12% for Japan (KDI 2000; see Carre et al. 2000). What is noteworthy about all of this is that while the number of nonstandard workers in other OECD countries has gradually increased, Korea witnessed a rapid expansion in the last few years. Employment instability and underemployment is thus the core of the social crisis. Under the pressure of the so-called structural adjustments, the labor market began to be extorted. The proportion of involuntary unemployment has steeply increased, and youth unemployment has become a severe social problem. Long-term unemployment has increased absolutely and relatively, while the duration of unemployment has been systematically extended. The percentage of non-regular job workers has also increased greatly. Furthermore, the Korean labor market has made the cleavages even more crystallized between the employed and the unemployed and between regular and non-regular jobs, accelerating the polarization of society (Park 2004, 158-160). The emerging questions are how all of these uncertainties and the harsher environment have changed the way Koreans think about work and how their work ethic has changed. To put it another way, the question that concerns us is how the “cruel” world of work has inspired a change in the perception of work among not only those seeking jobs but also those with jobs. In view of these questions, we examine how Korean workers’ work ethic has become more realistic and self-centered. For instance, the paper shows how layoffs and job insecurity have forced workers to become more self-interested and practical about their work and jobs, developing an attitude of “I work only as much as I am paid.” It is also apparent that the camaraderie that used to rule supreme among colleagues is increasingly being replaced by competition. Now, the “us” versus “them” mentality is being increasingly, albeit discreetly, replaced by the “I” versus “you” attitude within the new work environment. The paper also shows how recent changes in the workplace, especially increased job insecurity, have led to a deterioration of job satisfaction among Korean workers. In addition, the paper examines how job selection considerations among jobseekers have changed.

Various Meanings of Work Ethic

In the sociological tradition, the notion of work ethic, especially those aspects pertaining to the mobilization of labor force commitment to work, has been regarded as one of the most important prerequisites of social change. In Weberian terms, it has been argued that the creation of a work ethic plays a significant part in promoting industrialization (Weber 1904/1958). As E. P. Thompson (1967) noted in his classic article, creating an industrial labor force entails a severe restructuring of working habits and work ethics—new disciplines, new incentives, and a new human nature—upon which a new system can be effectively built. Because of its crucial implications, there have been many attempts to define and measure work ethic. Broadly speaking, work ethic refers to a set of values based on the virtues of hard work and diligence. The most common definitions or idealization of work ethic tend to portray a person as someone who values hard work and displays personal qualities of honesty, asceticism, industriousness, and integrity (McCortney and Engels 2003, 136). Furnham (1987) notes that work ethic has been defined as a culturally socialized norm, a constellation of individual qualities, a dispositional variable of personality, or a facet of internal locus of control. In each of these definitions, it is possible to see the constants of internal attitudes and external behaviors. The general issues reflected in the literature concerning work ethic suggest that research tends to cluster around two primary aspects: its internal characteristics, as held by individuals, and its external characteristics, as exhibited in work behavior (McCortney and Engels 2003, 134). While the former literature tends to reinforce the view that work ethic is related to individually held internal values, the latter literature tends to reinforce the view that work ethic is related to socially held cultural values.

Since Weber’s (1904/1958) theory of the Protestant work ethic, scholars find a popular construct around which a number of scales have been developed (a) to identify personality traits associated with work ethic; (b) to measure the importance of work in the lives of individuals; and © to describe behaviors related to both (a) and (b) (Murdrak 1997; Wentworth and Chell 1997). Also, it is widely noted that Weber’s view of changes in the economic structure regarding work seems to have particular relevance to the continuing restructuring of work ethic. For instance, social effects of unemployment are correlated with family disintegration. If work gives or is perceived to give an individual dignity, then not working removes the individual’s dignity. The implications of this perspective are chilling in an era of the temping of the workforce through contract work and repeated instances of involuntary unemployment (Bridges 1994; Rifkin 1995). Also, the notion of work ethic in conjunction with a social crisis might be conceptualized as a kind of uneasy compromise. Implicit in the understanding of work ethic is that what might be perceived as a social contract includes some key promises: the ability to afford both necessities and luxuries, the idea that an individual’s basic needs will be provided for, physical safety, economic gain, and psychological fulfillment. The compromise for individuals seems to be that, if they work hard, these benefits will undoubtedly accrue (Rifkin 1995). In other words, hard work pays off in the long term. However, economic turbulence, unemployment, underemployment, flexibilization of the labor force, and corporate downsizing seem to threaten the old promises of work ethic.

All of these conceptualizations of work ethic point to the fact that the concept of work ethic has multiple meanings and implications, pertaining to a variety of aspects related to work, including work commitment, work value, attitude toward work, occupational value, organizational commitment, perception of career development, and work achievement. And these conceptualizations and meanings have been used as frameworks for measuring various aspects of work ethic. In the Korean context, there has been active research on all of these aspects of work ethic, most notably by the Korea National Statistical Office (KNSO) (1996, 1998, 2001, 2004) and the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (KRIVET) (1998, 2002; see also Kim and Yi 2000; Yi 2003; Jang and Jo 2004). The findings of these studies have received extensive scholarly and media attention, but none more so than after the 1997 financial crisis. What drew the academic and public attention to this issue was the very question that our paper is addressing, i.e., how has the perception of work and work ethic changed among the populace after the proverbial lifetime employment and camaraderie among colleagues have been replaced by job insecurity and greater competition among workers?

Changes in Work Ethic among Korean Employees

Less Commitment to Work and Company

It was noted above that the lifetime employment and job security of Korean corporate culture have given way to layoffs, early retirement, and job insecurity following the 1997 financial crisis. In reaction to all of these uncertainties and harsher corporate environment, workers have become more realistic about their career and more self-centered: the thought of lifetime employment and blind loyalty has changed to one of “I work only as much as I am paid” or “the only things I can trust are myself and money.” Indeed, the fear of being laid off has inspired many Korean workers to be more concerned with making a lot of money in a short time. This was one reason for the relatively high job turnover rate during the boom in venture firms between 1999 and 2001, when many young conglomerate workers left their jobs to work for venture firms that promised a large financial reward in the form of stock options on top of the salary. The rationale for these workers seems to have been that although job insecurity was not improved, they could at least hope to make a lot more money by switching to the new company. In the rapidly changing work environment, it seems that workers’ anxiety is intensifying over the uncertainty of their future and that money—having a lot of it—is the only way they can feel secure about themselves. What this example indicates is that Korean workers’ loyalty to their company seems to have greatly diminished in recent years (Kim and Park 2003). This is particularly true for white-collar workers, who are now much more conscious of their pay and future than ever before and are prone to calculating whether they are getting paid enough for the amount of work they put in.

Korean workers are also well aware that hard work alone no longer guarantees that they can remain with the same company for a long time. The prevailing thought is that one can be deserted by his or her company as easily as he or she is ready to leave. The declining loyalty or attachment to the company is attested to by the fact that a substantial number of workers are constantly looking to switch jobs that offer better pay and benefits. It is said that workers today, while working hard, always carry with them a letter of resignation and resume. Surveys readily demonstrate that Korean workers’ commitment to their work is low.4 Despite the Korean reputation for hard work, a poll of 20,000 workers in 33 countries by the multinational survey firm Taylor Nelson Sofres (TNS) found Korean workers to be the least committed to their work (TNS 2002). In the TNS survey, which assessed employees’ commitment to their type of work and company, Korea ranked last in employee commitment to work, with just 36% of the respondents expressing their dedication to their work. The score was far less than the global average of 57%. The survey also showed that only 35% of Korean workers were committed to the company they work for, putting Korea in 31st place in the category. Moreover, only 25% of Korean workers were found to be committed to both their work and company, which was much lower than the global rate of 43%. The industry sector with the most committed employees in Korea was the public sector, which is quite understandable given its reputation for job security, relatively high salaries, and generous fringe benefits. The least committed Korean workers by sector, on the other hand, were in manufacturing, while the company type with the least committed workers was transportation. A 1997 survey by Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (KRIVET) and a follow-up survey in 2002 also reveal workers’ declining commitment to work. When asked about their willingness to use their personal money for carry out their occupational tasks and to work overtime, the respondents’ answers declined considerably from 1997 to 2002. On a related question of whether they were willing to participate in family affairs during working hours, more respondents were affirmative in the 2002 survey.

Another change that is indicative of workers’ lower commitment to work is how their sense of priority has changed. Workers now value their family more than work, which has not always been the case. That is why it is said that the idea of home has changed from being a place to return to from work to a place one leaves to go to work. This change in attitude is likely to have led to more workers leaving their office not long after the required working hours. In the past, of course, Korean workers boasted of their long working hours in the office. This greater emphasis on the family also has led to their desire for more quality time with family as well as becoming more concerned with various quality of life issues, among which job satisfaction has become an important factor for switching jobs. A popular saying in this regard is “I like my job, but I don’t like my work” or “I like my work, but I don’t like my job,” either of which now serves as the main reason for quitting a job to start a business or switching jobs. Collectively, what Korean workers seem to be expressing is their discontent over the rigid hierarchical company culture and the unsuitability of the types of duties and tasks they perform at work. They keep questioning how their unsatisfactory and mind-numbing work can complement their lives. They also complain about the lack of free time to develop other skills and aptitudes. All of this reflects the conspicuous change among workers’ perceptions in which work is increasingly viewed in terms of one’s inclination, preference and desire as well as quality of life issues.

Increasing Job Dissatisfaction

The surveys on job satisfaction, which included, among others, questions regarding types of work, relationships with coworkers and superiors, working conditions, and promotional opportunities, show that workers’ overall job satisfaction declined noticeably between 1997 and 2002. In the 1997 survey by KRIVET, the proportion of the respondents who were either very satisfied or satisfied amounted to 75.7%; however, the rate fell to 67.6% in 2002 (KRIVET 2002, 214).

Other surveys further demonstrate workers’ increasing dissatisfaction with various aspects of work, including job security, wage levels, working conditions, and opportunities for promotion. A survey of the members of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) shows that 59% of the respondents expressed dissatisfaction with their work (Kang 2002, 308-309). One of the key reasons for their increasing dissatisfaction seems to be job insecurity brought on by restructuring. In another study of KCTU workers in 1998, the respondents’ views regarding wage levels, promotion opportunities, working conditions and fair treatment were evenly divided between being either satisfied or dissatisfied. However, a 1999 survey showed that a considerably larger number of workers were more dissatisfied with their work.

Increasing job dissatisfaction has a lot to do with job insecurity caused by layoffs. Soon after the financial crisis began, for example, it was widely recognized that those who survived layoffs in large conglomerates showed that they developed so-called ADDS or After Downsizing Desertification Syndrome, meaning that they felt mentally desolate after seeing their colleagues dismissed from work, and were prone to feeling guilty. Job-keepers also reportedly suffered from the “survivors’ lament”: continuing job insecurity, work overload, and stress from working in unfamiliar settings if dispatched to a different department through restructuring. A recent survey of workers by a job search firm indeed shows that work overload and job insecurity are two of the top three reasons for work-related stress and that such stress was severe enough for more than a third of the workers to seek medical treatment (TNS 2002). Other recent surveys further demonstrate that workers are constantly worried about being laid off. For example, a survey of workers in early 2005 showed that 62.8% of those polled expressed their fear of layoffs (ITjobpia 2005). The extent to which this fear is felt by workers is manifested in the popularity of such terms as “사오정" (“retirement age of 45”) and “삼팔선" (“retirement age of 38”), which became popular after it became known that recent layoffs have affected a large number of workers in those age categories. In fact, a survey of employees showed that nearly two-thirds of workers feel that their employment will be terminated before they turn forty (Findjob 2003). One of the biggest concerns in regard to all of these job insecurity and job-related stresses is that they can prompt a large number of core laborers to exit the labor market voluntarily in search of better working conditions overseas or establish their own business.

Increasing competition within the workplace is another contributing factor to rising job dissatisfaction in Korea. Indeed, the camaraderie that used to rule supreme among colleagues is increasingly being replaced by competition. Now, the “us” versus “them” mentality is being increasingly, albeit discreetly, replaced by the “I” versus “you” attitude within the workplace in the fight to survive layoffs (Sin 1998). There is also growing recognition that workers cannot survive without professional knowledge and skills in the highly competitive global era. That is why many workers use their free time for self-development. In addition to working hard, many white-collar employees sacrifice their free time in the early morning or evening, at lunchtime, and even on weekends to improve their English or obtain certificates of qualifications, such as a CPA. That is because English proficiency and certificates of qualifications, along with educational background and school ties, figure prominently in job promotions. While the penchant for learning English and acquiring other skills has been around for some time, it has become far more intense since the financial crisis. What is also different about post-crisis Korea is that individuals are making these sacrifices in preparation for possible layoffs, to better ready themselves for finding other jobs in the event of layoffs. Faced with an uncertain future, it is also true that many workers are constantly looking into the possibility of establishing small businesses of their own.

Changes in Priority in Job Selection Considerations

The heartless world of work, as it is now popularly perceived, along with the fear of unemployment, has also inspired a change in the perception of work among those seeking jobs. In the past, job security used to be of the least concern for those looking for a job, but it is now deemed more important than such issues as future potential and pay level. For example, a 1995 survey of 30,000 households by the KNSO (1996) showed that the top three priorities in considering a job were job security (29.6%), future potential (29.2%), and pay (27.1%), demonstrating that these priorities were considered evenly important. A survey three years later, however, showed a conspicuous change: 41.5% of the respondents chose job security as the most important issue in choosing a job, followed by 20.7% for future potential, and 18.2% for pay (KNSO 1998). A 2002 survey also shows that job security was still the top concern.

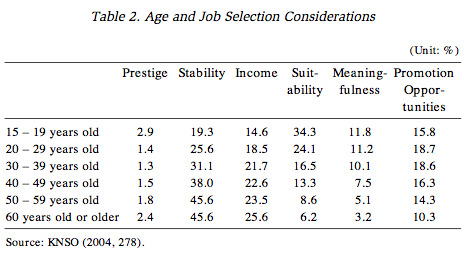

The 1995, 1998, and 2002 survey results show that job security is equally valued by both men and women. However, this tendency is stronger for those with relatively lower educational attainment. In the 2002 survey, for example, 43.3% of the respondents with an elementary school diploma or less chose job security as the most important consideration in job selection, followed by those with middle school diplomas (35.6%), high school diplomas (33.6%), and college graduates or above (27%) (see table 1). For those with low educational attainment, moreover, income level was the next most important consideration, with relatively little consideration given to the issues of suitability, meaningfulness, and opportunities for promotion. For those with college degrees or higher, on the other hand, the second most important consideration in job selection was suitability, followed by promotional opportunities and income. These trends were also observed in the 1998 data. What this shows is that those with lower educational attainment are more concerned with extrinsic rewards such as job security and income precisely because they are more vulnerable to layoffs due to lack of skills. Those with relatively higher educational attainment, on the other hand, valued more intrinsic rewards, such as meaningfulness and suitability.

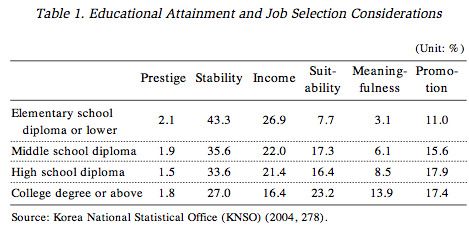

There appears to be generational differences in job selection considerations as well. The 2002 KNSO survey shows that for the 15-19 age group, the most important consideration in job selection was suitability, while job security and suitability were found to be almost equally important for those between the ages of 20-29. Their older counterparts, however, clearly showed their preference for stability in job selection (see table 2). The same was true in the 1998 data. What this shows is that the younger the respondents are, the more they emphasize intrinsic values in job selections, and that the older the respondents are, the more they emphasize external rewards.

Changes in the perception of work among women are also worth noting. In the surveys by the Korea National Statistical Office, the percentage of female respondents who agreed with the statement “I will continue to work irrespective of my marital status” increased from 24.7% in 1995 to 30.4% in 1998 and 40.2% in 2002 (KNSO 2001, 2003). Similarly, the proportion of women who said they would be full-time homemakers declined from 12.1% in 1995 to 8.5% in 1998 and 6.0% in 2002. In these surveys, the less educated and older respondents for both genders held more traditional views regarding female employment. The 1998 and 2002 surveys by KRIVET showed similar results. For example, the proportion of female respondents who said they will continue to work irrespective of marital status increased from 43% in 1997 to 44.9% in 2002 (KRIVET 2002, 227).

Another survey worth noting shows how women are more enthusiastic about work. For example, a poll by an online job portal showed that more female respondents (55.6%) than male respondents (44.4%) were willing to work as contract or dispatched workers if they are given a chance (Hankyorech 21 2004). This not only reflects the more difficult job opportunities for women, but also their greater enthusiasm for work. Such enthusiasm is reflected in the way women reportedly try harder than men in preparing for recruitment and job opportunities because they feel that they will not get the job if their qualifications are similar to those of men. All of this shows that work is no longer a matter of choice for women and that they have become more like men in seeing paid work as an important part of their identity and life.

Emerging Patterns of Job Mentality

The fear of being unemployed has led to other changes in the attitudes of jobseekers. A survey of senior students in universities by an online job portal showed that nearly four in five respondents answered “Yes” to the question of whether they were willing to work in production lines, i.e., factories, of major conglomerates (Hankyoreh, January 26, 2005). As for the reason, 42% of the respondents pointed to a relatively high salary, followed by 17.3% who noted the relative ease of getting such a job, and 15.8% who liked its greater job security. Another survey of jobseekers showed that a near majority of respondents (48%) stated that they are willing to work for a company irrespective not only of the duties required but also of the compatibility of their field of study with the required tasks (Hankyoreh, November 14, 2002). All of this shows that a growing number of jobseekers are moving away from being fixated on finding a position at a large conglomerate, which was once the most desired job, to more varied outlooks on occupation, whereby jobs at multinational corporations and smalland mid-sized firms are seen as excellent alternatives. Also, they are reportedly more open to the idea of launching their own business.

Another emerging pattern that deserves mention is a growing, albeit very small, number of young people who do not really care what kinds of job they have (Hankyoreh, September 17, 2003a). They care more about spending quality time doing things they like, rather then being trapped in the regimental and stressful world of work. For them, the only thing that matters is the guarantee of earning enough to enjoy their relaxed lifestyle. This means that they do not necessarily desire high-paying jobs nor do they strongly desire jobs that promise a certain level of job security or success. These young people, who can be clearly distinguished from job hoppers, are the socalled “neo-nomadic generation.” They are the kind of people who refuse regular jobs and who would sometimes opt to walk out of a well-paying job in order to pursue work they like, e.g., to work on a movie set or for entertainment events or to work as a freelance translator or online reporter. They refuse to be pressured by family obligations and reject the ideal of career success as defining a person’s sense of worth and happiness. These young people are growing in numbers, both domestically and internationally, and they develop many communities of their own, much of which is online. Collectively, their views and attitudes mark a clear departure from those of the older generations whose perceptions of work and job success as well as life in general tend to be tradition-bound and steeped in external rewards. All of this demonstrates the increasing heterogeneity of perceptions regarding work. While older generations were preoccupied with regular, full-time work, prestigious occupations, and career success, a considerable number of young people today opt to pursue jobs that are more suitable to their needs and liking. Also, it is worth noting that increasing incidences of late marriages, a steady increase in the number of unmarried, a declining birth rate, and a growing number of childless couples all can be said to be indirectly related to the rising number of neo-nomads.

What is also noteworthy is the rise of the so-called “kangaroo people,” a term which was first used in 1998 in France to refer to young people in their 20s who live with their parents and do not work or work only part-time. This trend is also evident in Korea. According to data from the Ministry of Labor, the employment rate as of July 2004 for young adults living on their own was 87%, while the rate for those living with their parents was nearly 20% less at 68%. The ministry also maintained that up to 40% of the unemployed young adults were voluntarily jobless, as they refused to work for reasons ranging from unsatisfactory wages and benefits to poor working conditions and unsuitable working hours. The rising number of jobseekers who are working part-time is related to this. While it is true that a majority of them are resorting to part-time work as a temporary measure before landing a full-time job, a considerable number of them actually prefer the less-demanding and flexible work schedule of transient work. Indeed, a survey of jobseekers by an online job portal showed that 55% of the respondents who were working part-time were doing so because they could not find regular work (한겨레, 2003b). For the rest of the respondents who were working part-time, their reasons were very different: 25% of the respondents said they held part-time jobs because they wanted flexible working hours; 11% wanted to avoid the stifling rigidity of corporate culture; and 5% did not want to endure the stress that comes with full time work.

It is also apparent that Korean jobseekers have become more global in their attitudes toward the location of work. That is, they are more than willing to go abroad to work: in a survey of jobseekers in December 2003, 90% of the respondents stated that, given the opportunity, they would like to go abroad for work (Hankyoreh 2003c). Nearly a third of the respondents who expressed this view were found to have actually tried to prepare for overseas employment. In regards to the reasons for their willingness to work overseas, the largest proportion of the respondents (35.1%) noted the “enhancement of their professional and work skills,” followed by “a bleak employment outlook in Korea” (18.6%), and “better benefits and working conditions at overseas jobs” (18%). In fact, the number of Koreans who have found overseas employment has increased noticeably in recent years. The number of Koreans who reported overseas employment to the Human Resources Development Service of Korea jumped from 5,520 in 2001 to 7,299 in 2002, 14,481 in 2003, and 22,091 as of July 2004. This sizeable increase in the number of work-related immigration also attests to the rising brain drain. For example, the number of outbound immigrants with skills in such areas as computing and electronics more than doubled from 3,287 in 1997 to 8,369 in 2000, marking the first time the number of work-related immigrants comprised more than half of the total of outbound immigrants in any given year in Korea. This trend continued in the next two years as 6, 079 out of 11,534 immigrants in 2001 and 6,317 out of 11,178 immigrants in 2002 migrated abroad as occupational immigrants (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade 1998, 2001-2003). A similar pattern of brain drain is found in the research and development community, where an estimated 5,000 researchers have left Korea between the end of 1997 and early 1999.

Conclusions

The 1997 financial crisis not only halted the nation’s decades-long economic development but also ushered in fundamental changes in practically every sector of Korean society, including lifestyle, worldview, employment pattern, and corporate culture. The sector that has undergone some of the greatest changes is the workplace. Lifetime employment, the age-graded seniority system, and a familial structure used to be the hallmarks of Korean corporate culture, but layoffs, early retirement, job insecurity and increased competition have become the realities of the workplace since the financial crisis. In reaction to the harsher world of work, the work ethic of Korean workers and jobseekers has naturally changed. First, Korean workers are found to be less committed to their work and their job. Their sense of priorities has changed, whereby they value family over work. Also, their sense of identity is no longer primarily based on their work and job. Prior to the financial crisis, the most important mechanism through which Korean workers derived their identity was their work and job. In fact, their work and job was everything to them; their identity could not be separated from those entities. Workers closely identified with company goals and took great pride in thinking that the success of their company was very much of their own making. Also, whatever one achieved at work was for the good of the company, and whatever the company achieved was for the good of the employees. This was largely possible because of lifetime employment and the company culture that was much more familylike than it is now. However, such attitudes and thoughts have largely disappeared. The companies they work for are no longer perceived as entities to which they need or want to devote their loyalty beyond what is necessary. Companies, which can let them go at any moment, are no longer perceived as a haven away from home or as a refuge from the cruel world outside. In fact, the prospect of layoffs and cutthroat competition within the company make it the very source of stress and heartlessness.

Second, Koreans’ work ethic has become more self-centered and individualistic, as they are much more conscious of their pay and working conditions. That is why large numbers of workers are constantly looking, if not trying, to switch to jobs that will offer better pay and benefits.

Third, job satisfaction among Korean workers has declined. This is partly due to changes in company culture: companies can freely resort to layoffs in scaling down their payrolls; companies are much more demanding of worker’s greater productivity in the age of global competition; and companies are much more strict with promotions. All of these changes have turned the workplace into one of harsh competition, causing great emotional strain for workers.

Finally, there has been a significant change in job selection considerations. In the past, job security used to be the least of concerns for those looking for a job, but it is now deemed more important than such issues as future potential and pay level. Accordingly, gone are the days when positions at a large conglomerate automatically topped the list of jobseekers. Those jobs are still regarded highly, but there is now greater diversity in job preferences. Aspiring workers increasingly prefer employment as civil servants and teachers, as these jobs offer greater job security, albeit with relatively smaller pay and less prestige. Jobs at smallto mid-sized firms have also become popular for the same reason. Multinational companies stationed in Korea are also popular among aspiring workers, but for different reasons. They are admired in the belief that they offer better pay and a more relaxed company atmosphere. An implication here is that some of the most able would-be-workers for conglomerates are now opting for more secure jobs; therefore, conglomerates can no longer be complacent when it comes to recruiting the most talented workers.

What all of this shows is that Korean workers’ identities are no longer homogeneous. Following the financial crisis, working conditions and types of employment have become much more varied, leading to the gradual diminution of collective consciousness. It is also clear that Korean workers are now less likely to derive their identity from their membership in workplace and labor unions. This is clearly seen in the way labor union membership rate has steadily declined over the years, implying that workers are moving away from a group or communal orientation. The growing individualistic orientation of Korean workers could be a reflection of a societal trend, but it could also be seen as a by-product of the workplace that is becoming increasingly impersonal and competitive, not least because of the fear of layoffs.

0 notes