Scott M. Rodell, Insights into Chinese Sword - Taiji Fist - Manchu Bow

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

youtube

#swordfight#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordwork#jianfa#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Received a wonderful gift from one of my Russian students, Ал Сашира Сашнева, today.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Republican Era Chinese Jian with clearly visible differential heat treating of the edge plate that creates a very hard edge. This harden edge makes it excellent for cutting, and it holds its edge quite well. However, the same hardness than makes for superior cutting effectiveness also means that the edge is relatively brittle. For this reason, Chinese Sword Arts standardly deflect with the blade flat rather that parrying with the edge.

Hard blocks with sanmai (three plate) type swords, those of China and Japan, with the edge can lead to a catastrophic failure of the blade.

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#chinesemartialart#chineseswordart#chineseswordwork#swordarts#daoistswordarts#zhongguojianfa#中國劍法#劍法#劍#chineseswords#kungfuweapons#historicalswordsmanship#taijijian#taichisword

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#chineseswordplay#chineseswordfighting#daofa#miaodao#qijiguang#dandaofaxuan#dandao#chineseswordarts#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#scottmrodell#swordplay#chinesemartialart#historicalsword#historicalswordsmanship#chineseswordsmanship#ukchineseswordfighting#swordarts#twohandedsword#chineselongsword#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merging Jianfa & Daofa in Your Swordplay:

Practitioners of Jianfa looking to explore the depths of Chinese swordsmanship, incorporating Daofa, the art of the saber, can add a more assertive, power orientated flavor to your swordplay.

This journey is not just a weapons switch up; it's about expanding your mindset, augmenting your skill set, while broadening your approach to swordsmanship.

In this guide, we'll navigate through the transition, focusing on practical techniques and insights to enhance your martial arts skills.

The Jian, with its straight, double-edged blade, epitomizes precision, agility, and adaptability, demanding a level of finesse and fine movement.

In contrast, the Dao, featuring heavier cuts, is a single-edged blade, representing power and efficiency in combat.

Uniting Daofa with Jianfa involves more than learning to handle a different sword, it means embracing a different approach in swordplay.

The Dao's point of balance is more forward than the Jian’s. This provides for more powerful cuts and thus a significant shift in technique. Daofa focuses not on the quick, wrist-led maneuvers that are the essence of Jianfa, instead focusing on powerful, elbow-driven techniques.

This style engages larger muscle groups for stronger and more impactful strikes, a key aspect in effectively wielding the Dao.

Starting with Pi Cut from Stirring Deflection

Begin your transformation with a drill common to both Jianfa and Daofa, the Pi cut from a stirring deflection. This provides a familiar base while introducing Dao's unique handling characteristics.

Chan involves a binding or wrapping movement, where the blade circles the body. It's a deflecting technique where the flat of the blade is used to deflect an incoming cut on one side of the body and then continues the motion to circle the blade around the torso, behind the back. This allows for a follow-up cut from the opposite side.

Deflecting with a Chan movement, the empty hand moves inside the blade, close to the chest, and can be employed to momentarily control the opponent’s sword arm as one advances forward. Training this technique introduces practitioners to the closer, more direct combat style found in Daofa. In contrast, Jianfa's prefers maintaining a distance that provides space to maneuver.

After gaining familiarity with the Pi and Hua cuts, it's insightful to progress to the distinctively heavier Kan cut. The Kan is and unique to saber systems, not being present in Jianfa.

Following this, the Duo cut would be the next logical cut to add. While the Duo cut is also present in Jianfa, it’s not made use of as frequently when wielding the straight sword.Training Daofa’s use of the Duo reminds us of why we are evolving our swordplay, merging the mindsets of Jianfa and Daofa, mixing more aggressive and assertive actions into our sword work.

In practice, although the timing of the Duo cut may appear similar to its Jianfa counterpart, it requires a considerably larger window of opportunity, reflecting the bolder and more direct approach of Daofa.

This exploration into the Duo cut provides practitioners with a new perspective on the rhythm shift from the more measured Jianfa to the dynamic and forceful Daofa.

The Pi cut can be likened to the power needed to trim a leaf off a tree, the Kan cut to chopping a thick branch, and the Duo cut to the robust action of felling an entire tree or splitting a log. This progression not only illustrates the escalating power inherent in Daofa techniques but also underscores the distinct tactical mindset required for this style of swordplay.

The Gua cut, though mechanically akin to the Liao cut in Jianfa, takes on a unique role in Daofa. It focuses an aggressive sweeping action to proactively capture the line, reflecting Daofa's assertive and power-oriented nature of Dao swordplay.

Incorporating shield work, especially with durable circular cost effective riot shields, provides insight into how the Dao would have been wielded on the battlefield. This practice not only enhances sword skills but also offers a better understanding of strategic defense and offense in historical combat contexts.

You can use a rattan Tengpai, but these are a lot more costly than a riot shield, which are far cheaper and will hold up to virtually anything you can throw at it during swordplay.

These individual cut drills can be combined into dynamic semi-fixed sparring routines, crucial for experiencing the reactive and adaptive nature of Daofa and preparing for unpredictable combat situations.

Merging Jianfa to Daofa offers an opportunity to evolve your understanding of Chinese swordsmanship, introducing new techniques and strategic thinking. It also adds tactical options to your swordplay, making you less predictable. This journey, embraced with dedication and an open mind, not only enhances your swordplay skills but also enriches your overall approach to swordsmanship. Enjoy the growth and mastery that come with learning the powerful art of the Daofa.

—----

All of the drills and cuts discussed in this guide can be found in the Daofa sections of the Academy of Chinese Swordsmanships Online Archives. Available to all members of the Daofa and Sword Scholars Study paths.

Visit www.chineseswordacademy.com for more details.

#chineseswordsmanship#jianfa#duanbing#chinesemartialarts#chineseswordplay#chineseswordfighting#scottmrodell#jianshu#daofa#scottrodell#daoistswordarts#chineseswordarts#swordfightingclasses#ukchineseswordfighting#taijijian#taijiswordfencing#taijisword#wudangsword#wudangjian#taijidao#taijisaber#swordfightingschool#kungfuweapons#swordfightingskills#chineseswordwork#swordtraining#劍法#刀法#chinesesword#yangjiamichuantaijijian

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#jianfa#jianshu#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#chineseswordsmanship#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#chinesemartialart#chineseswordarts#xingyijian

0 notes

Text

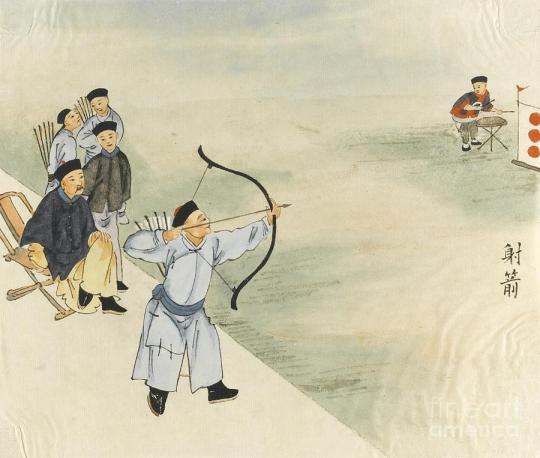

Manchu Archery Canton, 1861.

#manchubow#manchuarcher#manchuarchery#traditionalarchery#chinesearchery#qingdynasty#qingarcher#qingarchery#chinesehistory#wayofthebow#archery

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Need Your Input!

Hey everyone! We're reaching out to our current and potential students about Chinese swordsmanship. We want to make our classes and resources better for you.

What's Stopping You?

What are the main obstacles or issues you're facing in learning Chinese swordsmanship? Is it finding time, understanding the techniques, or something else? Let us know in the comments.

Your Feedback Matters

Your feedback is crucial. It helps us understand what you need and how we can improve. So, please, take a moment to tell us about your challenges.

Join the Conversation

If you haven't joined us yet, this is your chance to be part of a community that's all about learning and growing in Chinese swordsmanship. We're here to help each other. Join the Practical Chinese Swordsmanship Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/chineseswordacademy

Thanks for helping us make the Academy of Chinese Swordsmanship the best place to learn and practice this art.

#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordsmanship#jianfa#duanbing#chinesemartialarts#chineseswordplay#jianshu#scottmrodell#chinesemartialart#chineseswordarts#daoistswordarts#daoistswordsman#swordfightingschool#swordfightingskills#swordfightingclasses#scottrodell#ukchineseswordfighting#chineseswordwork#taijijian#taijiswordfencing#taijisword#taichisword#wudangsword#wudangjian#楊家秘傳太極劍#kungfuweapons#yangstyletaichichuan#yangstyletaichi#太極劍#taijifencing

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick Draw with the Rodell Cutting Jian -

Some 5 plus years ago, I began working on reconstructing Chinese Fast Drawing Techniques. Here’s my early effort.

Thoughts on Sword Tricks...

During my winter break from seminars, I thought I would have some fun and try my hand at a few sword tricks from different traditions. In all honesty, some of the tricks preformed are essentially just that, tricks. What I mean by that is that they do not embody any skill a swordsman might actually use in a duel. And so, they don’t provide the swordsman with any useful training. They are just for entertainment.

When I started practicing throwing an apple in the air, cutting it, I was thinking it was just a trick and it might even be fairly criticized as showing off. (I bought a bag of small wiffle balls to practice with in the wuguan. I didn’t want to waste food). And there is certainly a trick to this trick. You have to throw the ball or apple where you can cut it. You have to practice throwing the same height each time too, so that he pacing is always about the same. You have to practice the timing of the throw and draw. It is easy to watch the ball or apple too long and draw late. So as I practiced, usually in the short time after dinner and before students arrived for the evening classes, I observed other useful aspects of this practice. For example, the delay I mentioned. You cannot separate watching the target and cutting. When you do, the body and mind and essentially separate for a moment. When you start to cut, there is a delay, and you tend to miss.

As when shooting arrows, if you start thinking about how you are doing well after hitting several in a row, your mind is elsewhere and you are probably going to miss the next one. There is also a tendency to over swing after the cut. This is a common error in most students’ cutting. The control of the after cut is the most difficult aspect of good cutting technique. If you let yourself start chasing the ball, you tend to swing like you are trying to hit it out of the park.

In a way, practicing cuts That one normally would not is like any different sort of training that takes one out of comfortable territory. Any sort of new cutting provides a fresh look at one’s skills. A fresh opportunity to critique one’s practice. So in hindsight, I am finding sword tricks I did for amusement to be an unexpected and useful test of my skills. Not in the sense that these are difficult or physically demanding cuts, but in the sense that they gave me a clean look at my practice. In a way, what does it matter if a cut is just a “trick?” Perhaps what is more important is how one makes use of practice time?

Then again, no big deal, baseball players hit balls all the time.

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#scottmrodell#daoistswordsman#chinesesword#chineseswordarts#taijijian#taijiswordfencing#taijisword#chineseswordfencing#chineseswordplay#testcutting#tameshigiri#swordclass#swordfightingskills#swordfightingart#swordfightingschool#wudangjian#kungfuweapons#chinesemartialart#chineseswordfighting#jianshu#yangjiamichuantaijijian#yangstylestaijiquan#yangfamilytaijiquan

1 note

·

View note

Text

? SWORD Geek ?

Then You Are Going to Love Chinese Sword Fighting!

Unlock the power of Chinese Swordsmanship on a practical and thrilling level. Our online training encapsulates full-contact, realistic swordplay, honing not just your technique and skill but your understanding of this ancient battlefield art tailored for the modern martial journey.

Dive into a Realm Where Steel Meets Skill

Our comprehensive program is designed to cater to both novices and seasoned sword practitioners. Here’s what’s awaiting you:

Attend live weekly webinars, fostering direct engagement, and dynamic feedback.

Dive deep into hundreds of hours of recorded webinars. Learn, revisit, and refine your techniques at your convenience.

Pursue a curriculum forged through ages, battle-tested, and refined for a focused and ever-evolving martial journey.

Embark on a 7-Day Free Trial

Join us today and take the first step towards mastering the ancient art of Chinese sword fighting!

Begin with a 7-day free trial, and continue confidently with our 30-day money-back guarantee.

Are You Ready to Unleash Your Inner Swordmaster?

This isn’t just a hobby, it’s a calling. It’s about honoring age-old traditions while forging new friendships. It’s where nerdy meets warrior. So why wait?

Join Today & Immerse Yourself in the World of Chinese Sword Fighting!

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#scottmrodell#swordplay#chinesemartialart#zhongguojianfa#ukchineseswordfighting#chineseswordarts#daoistswordarts#taijiswordfencing#taijifencing#swordfightingclasses#swordfightingschool#劍法#楊家秘傳太極劍#yangjiamichuantaijijian

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#chineseswordsmanship#jianfa#duanbing#chinesemartialarts#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#scottmrodell#swordplay#ukchineseswordfighting#ukswordfighting#taijiswordfencing#taijifencing

0 notes

Text

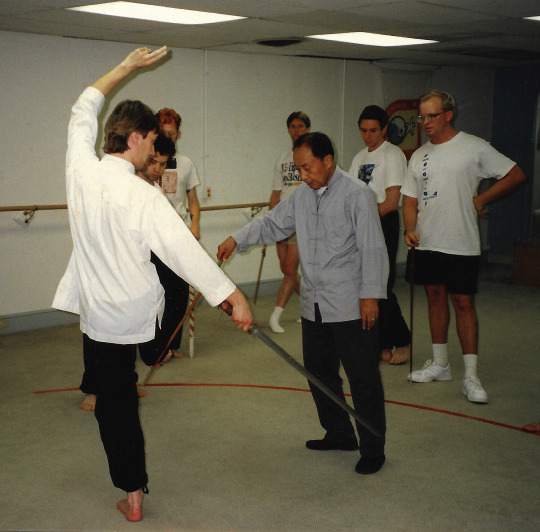

Wang Yen-nien schooling Scott M. Rodell on the finer points of the Yangjia Michuan Taiji Sword Form (楊家秘傳太極劍).

This Sword Form lies at the core of our Sword Work at the Academy of Chinese Swordsmanship.

We also draw upon the Ming period Two-Handed Dandao, the Four Roads Miaodao, the Yang Style Taiji Sword and Saber, and the WW2 Dadao.

#楊家秘傳太極劍#jianfa#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#scottmrodell#chineseswordplay#太極劍#swordclasses#scottrodell#wangyennien#chineseswordarts#chineseswordwork#ukchineseswordfighting#taijiswordfencing#taijisword#swordtraining#劍術#taijijian#chinesesword#chineseswordsman#yangstyletaichi#kungfuweapons#daoistsword#daoistswordsman#swordarts#historicalswordsmanship#swordfightingschool

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Typical Qing/Manchu style of target with a single bullseye.

When shooting in the Imperial Exams, credit was given for hitting anywhere on the target. But I alway light the idea represented by a single bullseye, that the shot that really counts is hitting the center

#manchuarchery#chinesearchery#chinesearcher#manchuarcher#qingarchery#traditionalarchery#qingarcher#bannerman#qingbannerman

1 note

·

View note

Text

Great Times at the Summer Retreat in Poland

Krzysztof, seen on the left, has long legs and quite a reach. John on the right looks to nullify that advantage by slipping back and positioning his Jian for a Tiao cut from below.

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#chinesemartialarts#chineseswordplay#duanbing#chinesemartialart#jianshu#劍法#太極劍#yangjiamichuantaijijian

1 note

·

View note

Text

Twilight Jianfa!

After training 3 days at Rodell Laoshi’s St. Paul Seminars, they wanted to test their sword skills. So out they went to the local plaza for some friendly bouting.

Seen on the left is Richard Son Su Meyer, director of Great River Taoist Center Twin Cities. And on the right is Quinatzin De La Torre. Both are long time students of Rodell Laoshi.

Note that both have years of experience in full contact swordplay and are able to control the power of their blows, even at full speed. Less experienced practitioners must don proper swordplay armor, particularly head and eye protection, when bouting.

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#chinesemartialarts#scottmrodell#duanbing#chinesemartialart#swordplay#taijijian#taichisword#yangjiamichuantaijijian#taijiswordfencing#chineseswordfencing#kungfuweapons#swordfightingclasses#swordfightingskills#swordfightingschool#daoistswordarts#daoistswordart#chinesesword#swordarts#swordfight#swordfighter#wudangsword#chineseswordwork#wudangjian#fullcontact#ukchineseswordfighting

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

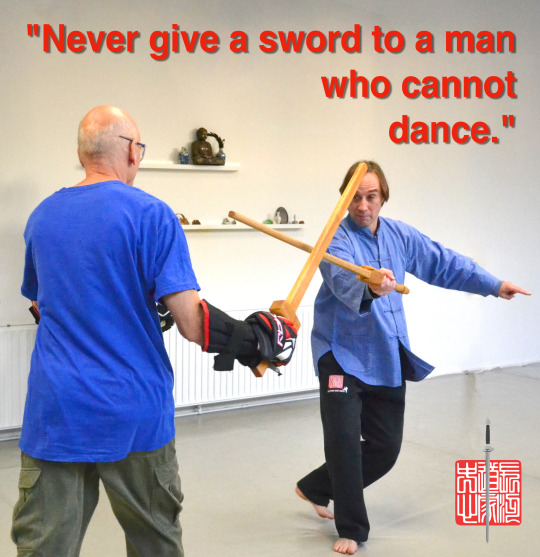

"Never give a sword to a man who cannot dance.” Or at least Confucius is reportedly said so, though this quote is more likely apocryphal than genuine. If he had did indeed written this, Confucius would have no doubt have been using it as a metaphor for not placing someone in a position they are not qualified to fill. If we take this idea literally, then Confucius probably would have actually meant dancing when asked whether or not to trust someone with a Jiàn. Though probably not the sort of dancing you are thinking of. Confucius lived during the later Zhou dynasty (ca. 551–479 BC). During his life, and in many dynasties to come, “Sword Dances” were performed as ritual. The term Jiànwǔ (劍舞, literally, sword dance) was also used to describe the forms used to train soldiers. Minority peoples also practiced war dances to prepare for combat. These ritual court and religious dances required a high degree of precision, flow, and intent. Which is to say nothing of good body mechanics. As do forms practiced by large numbers of men at arms at close quarters when drilling. It then follows that if one is unable to “dance” well with a sword in hand, then it is also unlikely that he’ll flow well in swordplay. Consider if one cannot flow deftly, without hesitation, from one movement to the next in sword forms, or hesitates, rather than moving seamlessly from deflection to cut as one intent, then how can one expect to “dance” smoothly, like a swimming dragon, following and fluidly countering when one’s duifang’s sends blows are raining down?

Lack of preparation in the form of forms (“dances”), training in the Basic Cuts, partner drills, and a methodical progression from fixed step to moving swordplay practice, often results in the sort of slapping together of blades during swordplay derided by past sword teachers. One example from the manual, Zǐwǔ Jiàn by Huáng Hànxūn, advises, “Don’t mutually strike (swords) together at the same time…” And the Yang Family Taijiquan Skill and Essential Points by Huang Yuanxiu records, “The sword is never easy to pass down. Straight forward and back is incomprehensible. If you fake it, cutting like a saber, the old immortal Sanfeng will laugh to death.”

From a modern point of view, if you can’t “dance,” you should at least be cautious about jumping right into swordplay. Dancers move with the rhythm and flow of the music, and with their partners. They intuit the flow and use movements they’ve practiced to follow that pattern. Sounds a good deal like swordplay. If one hasn’t yet learned to “dance” beautifully through the sword form with the same sort of focus and intent of the ancient sword dances, don’t expect to flow with the duifang’s cuts as they rain down, it could be fairly easy to fall into the error

The fix is easy- Practice sword forms as if there’s a duifang there doing his best to cut you. Visual his movements and move with them. Train with a historically accurate sword to avoid misconceptions that arise from light weight, improperly balanced “weapons.” Practice your form mindfully to perfection and you’ll see a difference in your swordplay.

~Scott M. Rodell

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordplay#chineseswordfighting#chinesemartialarts#scottmrodell#duanbing#swordplay#chinesemartialart#scottrodell#yangjiamichuantaijijian#yangstyletaichi#yangstyletaichichuan#taijisword#taichisword#taijijian#zhongguojianfa#ukchineseswordfighting#swordfightingschool#swordfightingskills#swordfightingclasses#swordfighting#chineseswordwork#chineseswordarts#chineseswordart#taijiswordfencing#taijifencing

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

No matter how challenging the Push Hands, you can always smile.

Tallinn, Estonia Branch GRTC

#pushhands#pushinghands#tallinn#tuishou#yangstyletaichi#yangstyletaichichuan#yangstyle#yangjiamichuantaijijian#scottmrodel#scottrodell#chinesemartials#gongfu#kungfu#taichi#taichichuan#taijiquan#yangfamilytaijiquan

5 notes

·

View notes