#chineseswordsman

Photo

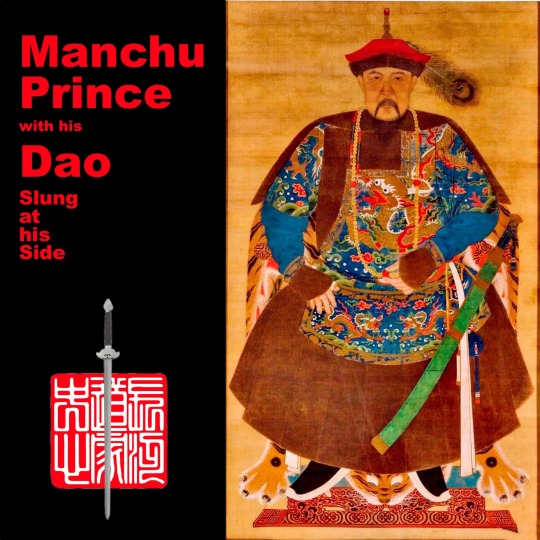

Qing Bannerman

The Dao was standardly slung with the hilt back in this fashion during the Qing period. Judging from this Bannerman's embroidered changpao and leopard skin jacket he is no doubt a high ranking officer.

#manchubannerman#bannerman#qingdynasty#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#historicalswordsmanship#chineseswordplay#duanbing#chineseswordwork#chineseswordarts#daoistswordarts#chinesemartialarts#中國刀法#刀法#chineseswords#chineseswordsman#chinesesword

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The history of the Chinese Fast Sword Draw (出劍法) dates back to the Han dynasty, 2,000 plus years ago. Unfortunately, there are no known manuals for these techniques and historically illustrations are rare. This depiction of a seated swordsman drawing his sword is from a scroll originally painted by Gu Kaizhi ( 顧愷之) in the 4th century. While Gu’s original version of this scroll, The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies (女史箴圖) has not survived, later copies of this work have.

The two following later copies of this scroll date to the Tang (dated between the 6th and 8th century AD) and Song dynasties. As such they are likely the oldest known illustrations of a Chinese Swordsman Preforming the Fast Sword Draw (出劍法). They are also the only know depiction of a seated Chinese sword drawn know to date. Given the age of the two paintings, it is difficult to make out the finer details. What we can see is that seated swordsman’s grip is palm out with his fingers wrapping over the grip prepared to draw and strike downward. His rear hand is well back toward the rear of the scabbard, palm down.

A skeptic might understandable suggest that the seated figure is actually wielding a cudgel. Given the lack of visible detail, this would be an understandable suggestion. However, there is no reason for a wooden club to be gripped at the rear end just prior to swinging it. And given that what appears to be bear is just before the seated man, if it were some sort of cudgel and not a sword ready to be drawn, it is more likely he would be gripping it with two hands not holding the the rear end palm down.

Note: the Tang period example of The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies is in the collection of the British Museum in London. The Song period (960-1279) example is the property of the Palace Museum in Beijing.

#出劍法#chineseswordsmanship#jianfa#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#scottmrodell#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#chineseswordsman#chineseswordarts#daoistswordarts#swordfighting#chineseswordfencing#taijiswordfencing#swordfightingskills#kungfuweapons#iaido#scottrodell#testcutting#jianshu#chineseswordart#swordarts#swordsmanship#historicalswordsmanship#swordplay#chinesesword#chineseswords#daofa

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

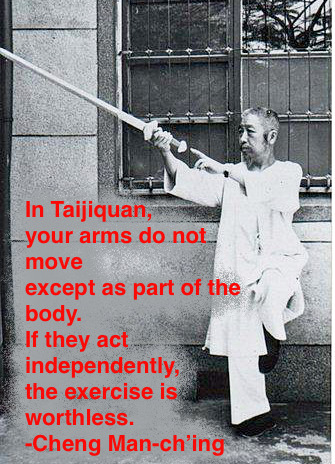

In Taijiquan,

your arms do not move

except as part of the body.

If they act independently,

the exercise is worthless.

-Cheng Man-ch’ing (郑曼青)

#jianfa#taijiquan#taiji#taichi#taichichuan#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordsman#chengmanchingtaichi#chengmanchingtaijiquan#chengmanching#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

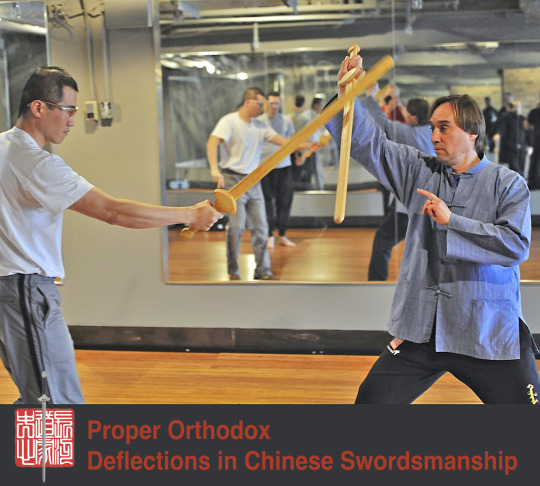

Attack and Defend Don’t Exist- Thanks to Essential Wave Studios for Re-Broadcasting My Post on Deflection in Chinese Swordsmanship: https://ewstudios.com/attack-and-defend-dont-exist/...

Full text of the Original Post Below...

Deflections in Chinese Swordsmanship

Recently, there’s been a reoccurring discussion of how Chinese Swordsmanship purposely deflects with the blade flat. Some today, not being familiar with the principles of the art, yet eager to practice, borrow edge parrying from European sword work. There are a number of reasons why both Jiànfǎ and Dāofǎ avoid edge on edge parries. These reasons include the Sānméi (three plate) structure of the blade. The high carbon, hard edge plate of Chinese swords make them excellent for cutting and maintaining an edge, but brittle in edge on edge encounters.

Beyond metallurgical reasons, Chinese sword work deflects with the flat for reasons of principle. The core principle of Chinese approach to swordplay is that each response to the duifang’s blow is not a dualistic defense then counter with an attack, but is one fluid seamless movement. There is no parry and riposte in either Jianfa or Daofa. There is, what in Mandarin is referred to as dānxíng (單形), literally a single or simple form. The act of deflecting is taking aim flowing into counter-cutting. Properly speaking it is a deflect-cut. One word, one action, no thought of defending then looking for an attack. There is mind intent with the deflection and at the target simultaneously as one larger whole. Attack and defense don’t exist in well practiced Chinese Swordsmanship. Deflecting with the blade flat not only aligns the counter-cut, being one continuous movement, it also generates power for the cutting action of the deflect-cut movement. Being but one movement, without any hard change in direction, no momentum is lost. The momentum of the deflection thus provides power to the cut it generates. For these reasons, Chinese swordsmanship focuses on solely using the blade flat to deflect.

~ Scott M. Rodell

#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#scottmrodell#jianfa#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#swordplay#chinesemartialart#scottrodell#太極劍#kungfuweapons#yangjiamichuantaijijian#chinesesword#chineseswordsman#劍法#中國劍法#劍術#swordclasses#swordtraining#taijiswordfencing#daoistswordarts#chineseswordwork#zhongguojianfa#ukchineseswordfighting#chineseswordarts#chineseswordart#daoistsword#swordfightingschool

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A scroll titled Countries Figure (Kunigni Jinbutsukan) in the Kyoto National Museum depicts a Chinese Military Officer carrying a Jian. This work apparently dates to the early Ming period. What’s interesting about this image is that this military man is carrying his Jian in his left hand, rather than having it suspended from his belt. While this depiction of the sword carried in the hand rather than strapped to the belt is not new, it suggestions the idea that this depiction is not simply the standard artistic convention as the Japanese envoy who painted this was apparently recording what he saw.

Another element previously observed is that the Jian is grasped not close to the center of balance when it is sheathed, but close to the scabbard throat.

#chineseswordsmanship#jianfa#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#jianshu#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#chinesemartialart#swordplay#chineseswordsman#chinesesword#taijiswordfencing#taijijian#taijisword#wudangsword#wudangjian#swordfighter#chineseswordwork#kungfuweapons#kungfu#mingdynasty#swordfightingskills

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WANT TO LEARN CHINESE SWORDSMANSHIP?

INSTANT ACCESS. ANYWHERE. ANYTIME.

Sign up for our FREE 7 DAY TRIAL.

https://www.chineseswordacademy.com/membershipsandcourses

Find a study path that’s right for you.

Simply put, the Academy was born out of a desire to continue to move forward during these demanding times. Training at the Academy centers on developing practical, effective skills. To that end, Webinars concentrate on hand and footwork in the context of full contact swordplay tested cut combinations.

We don’t teach forms, we focus on tried and true application. Practitioners from a wide spectrums for traditions, Xingyiquan, Baimei, Wing Chun, Baguazhang, Taijiquan, Tanglangquan, and others, as well as non-Chinese traditions, train at the Academy. We look forward to training with you.

Founded in 1984, Great River Taoist Center is 35 years strong. Chinese Swordsmanship is not the latest fad for us, it is a three decade passion. Center director, Scott M. Rodell, is a well know leader in the rebirth of the art being the first practitioner to practice test cutting with Chinese swords since imperial times. Along side his years of experience in historical swordplay and training under acknowledged masters, Rodell has penned nine books on Chinese Martial Arts. These include several translations of classic sword manuals.

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#jianshu#chineseswordplay#scottmrodell#duanbing#swordplay#chinesemartialart#chinesemartialarts#chineseswordwork#chineseswordsman#chinesesword#fullcontact#swordarts#taijiswordfencing#taijisword#taichisword#taijijian#yangjiamichuantaijijian#daofa#miaodao#chineselongsword#chineseswordfencing#daoistswordarts#daoistsword#wudangsword#wudangjian#kungfuweapons

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#qingdynasty#manchu#manchubannerman#manchurian#daofa#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordsman#chinesesword#chineseswords

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Chinese Full Contact Swordplay Tournament Dates are set, June 17 in the Washington, DC Area-

I’ll post the rules several places for those interested in competing. Note that Double Hits such as seen in this photo are not counted. When they occur, halt is called by the referee and the action centered. And then the bout continues from that point.

#太極劍#刀法#chineseswordsman#chineseswords#chinesesword#gongfu#kungfu#fullcontact#中國劍法#劍法#劍#chineselongsword#swordfighter#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#swordfightingskills#swordfightingschool#wudangsword#wudangjian#taichisword#taijisword#taijijian#daoistswordarts#daoistswordsman#daoistsword#chineseswordarts#chineseswordart#swordarts#swordart#chineseswordwork

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manchu Bannerman

I always find these Qing paintings interesting. They are a look back in time at the swordsmen of the Imperial era. Unlike the fanciful, sparkly uniforms many wear to tournaments today, these men dressed mostly in shades of blue and other muted colors. This Bannerman is wearing a tasset around his waist. These apron like garments were padded and sometimes made of leather. They could stop sword blows to the leg from cutting in and also protected the legs when riding through brush.

#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#daofa#chineseswordsman#bannerman#manchubannerman#qingbannerman#qingdynasty#chinesehistory#qinghistory#chinesemartialarts

1 note

·

View note

Text

PORTRAIT OF VAN-TA-ZHIN,

A military Mandarine (or Nobleman) of China.

This officer (a colleague of Chow-ta-zhin, who was a mandarine of the civil department) was appointed by the Emperor to attend the British Embassy, from the time of its arrival in the gulf of Pe-tchi-li, till its departure from Canton. Van-ta-zhin was a man of a bold, generous, and amiable character, and possessed of qualifications eminently suited to his profession, being well skilled in the use of the bow, and in the management of the sabre. For services performed in the wars of Thibet, he wore appended from his cap, a peacock's feather, as an extraordinary mark of favour from his sovereign, besides a red globe of coral which distinguished his rank. He is represented in his usual, or undress, consisting of a short loose jacket of fine cotton, and an under vest of embroidered silk; from his girdle hang suspended his handkerchief, his knife and chopsticks in a case, and purses for tobacco: on his thumbs are two broad rings of agate, for the purpose of drawing the bowstring. The heads of the arrows, which are thrust into the quiver, are variously pointed, as barbed, lozenge-headed, &cc. His boots are of satin, with thick soles of paper: these are always worn by the mandarines and superior Chinese.

From: THE COSTUME OF CHINA, ILLUSTRATED IN FORTY-EIGHT COLOURED ENGRAVINGS, WILLIAM ALEXANDER

#bannerman#manchu archer#manchuarchery#manchuarcher#qingdynasty#Qing Bannerman#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordplay#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#chineseswords#chineseswordsman

0 notes

Photo

The Ming period ran from 1368 to 1644, so examples of period jian are quite rare and are presumably often refit. Example of armor from the Dynasty are almost nonexistent. Fortunately we can turn to period paintings for a look at the arms and armor of the time.

This illustration is a close up from the Cónglánhuàn Jī Tú (丛兰宦迹图). It show a high official (Cong Lan 丛兰) in a scale armor vest with a typical Ming jian at his hip. The jian exhibits features common to Ming jian, namely that banded scabbard, the narrow shaped guard, and the open pommel with sword tassel running through it.

#mingdynasty#mingsword#chineseswords#chinesesword#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordsman#historicalsword#historicalswordsmanship#chinesehistory#minghistory

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hu Sanniang (扈三娘) is a fictional character in the Chinese classic the "Shui Hu Zhuan" (水滸傳) which is thought to be based in part on a band of bandits during the Northern Song dynasty. As a character, she may be taken to be an embodiment of those women in Chinese history that took up the sword. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hu_Sanniang

#chineseswordsman#chineseswordsmanship#daofa#swordsmanship#swordfighting#chineseswordplay#historicalswordsmanship#duanbing#chineseswordwork#daoistswordarts#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#gongfu#kungfu

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

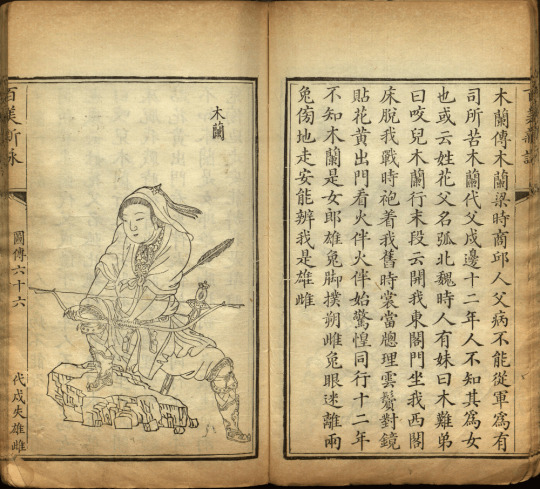

Mulan as depicted in a woodblock reprinting of New Poems and Pictures of One Hundred Beauties (c. 1800). The text provides a brief summary of the play Mulan Joins the Army and the Ballad of Mulan.

Mulan is perhaps the most widely know of Woman Jianke. To learn more of her history and story through the dynasties, see: https://mulanbook.com/

#Mulan#huamulan#jianke#chineseswordsman#swordswoman#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswords#chinesesword#historicalswordsmanship#duanbing#chinesehistory#gongfu#kungfu#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#chineseswordplay

23 notes

·

View notes

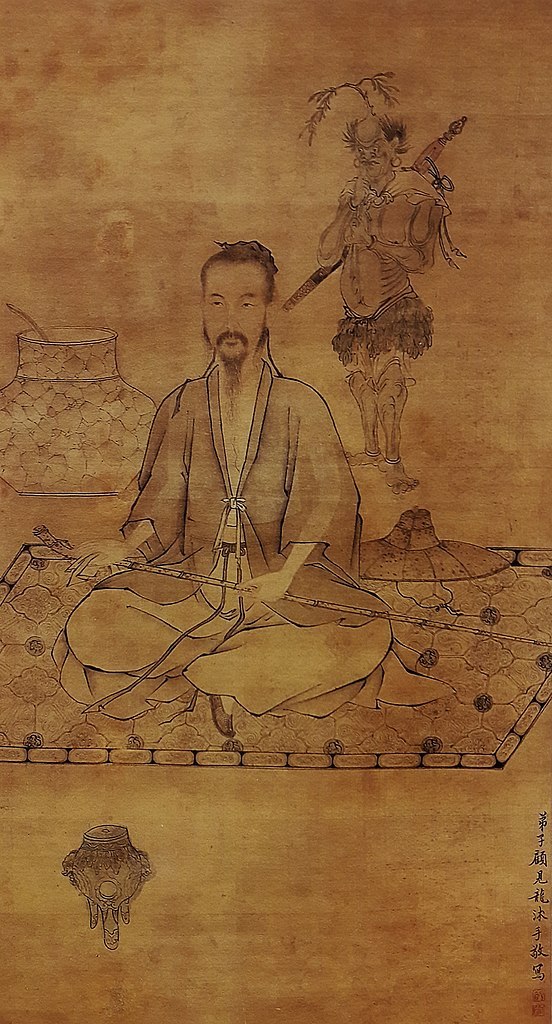

Photo

Gu Jianlong's Painting of Immortal Lü Dongbin

Can't see too much of his jian, but as typical for the period, note the open pommel.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ANONYMOUS (16TH CENTURY, PREVIOUSLY ATTRIBUTED TO LI CIGONG) Studying a Sword Hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk 143.5 x 72 cm. (56 1/2 x 28 3/8 in.) Inscription by Huang Ding (1660-1730), with three seals Two collector’s seals Titleslip by Lin Langan (1898-1974), with one seal

Source: https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-anonymous-16th-century-previously-attributed-to-li-6143471/

#chinesesword#chineseswords#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordsman#chineseswordplay#duanbing#daoistswordart#daoistsword#jianfa#jianshu#zhongguojianfa#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#sword#swords#historicalswords#chineseswordfighting

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

An in depth look at Chinese Short Swords. Please let me a comment on YouTube with a note about what you would like to see next...

#jianfa#jianshu#chinesesword#chineseswords#historicalswords#qingdynasty#qinghistory#historicalswordsmanship#swords#sword#chineseswordplay#chineseswordsman#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#duanbing#duanjian#daoistswordart#daoistswordsman

42 notes

·

View notes