Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

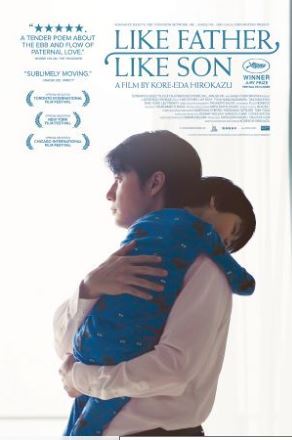

Like Father, Like Son

Nathan Souther reviews

In Like Father, Like Son, by Hirokazu Koreeda, several months in the lives of two very different Japanese families, who don't know each other at first but are thrown together into a strange, terrible situation with no easy answers, are shown. Ryomo and Midori Nonomiya, played by Masaharu Fukuyama and Machiko Ono, are a married couple who live in a nice apartment with their only child, Keita Nonomiya, who is six years old. Ryomo is a hard-working businessman from a traditional Japanese family, and Midori is a quiet, loving stay-at-home mom. Even though Keita is still young, Ryomo puts too much pressure on him to do well, even though they love him. Then, terrible news threatens to break the family apart: The country hospital where Midori gave birth to Keita calls the couple to tell them that they may have made a mistake six years ago by mixing up Keita's birth parents with those of another baby. DNA tests prove what the parents feared most: The child they've come to know and love isn't their own. It's the son of Yukari and Yudai Saiki, a working-class couple from a nearby town. They both gave birth in the same hospital at the same time, and they've been raising Ryusei (Shôgen Hwang), the Nonomiyas' son, along with their own children for years. The families get together and think about taking action against the hospital. However, this is not the most important question: how to change how they act with each other. Should the couples go on as before and act like nothing has changed for the sake of the sons they have raised? Or should they try to switch the kids and start over from the beginning? And if they choose the second option, what emotional and psychological effects will that have on the parents and sons?

This problem will probably seem more strange to people in the West than it does to the average person in Japan. Many people in North America and Europe, where adoption and surrogate parenthood are common, would think that the obvious thing to do in a crisis like this would be to keep the children and treat them as your own. But under the surface of modernity, much of Japanese society is still built on strict rules from the past that are based on the idea of blood lineage. To more traditional adults like Ryomo, the idea of raising another family's children is not only unthinkable, but also wrong and even sacrilegious. This makes the news from the hospital more than just upsetting; it feels like a direct attack on Ryomo. Koreeda's best work in this movie is making sure that all of these native differences, these invisible limits that hang in the air, are clear throughout the whole story. Other Asian imports, like Lee Chang-dong's play Poetry, could be hard to understand, but Like Father never is. When one of the characters acts in a way that seems strange to people in the West, we know where that behavior comes from.

The saga is uniquely Japanese in another strange but wonderful way: it feels like a family story. In place of a typical Hollywood story with an A-B-C progression and a predictable ending that strains credibility, Koreeda gives us a deliberately vague meditation that drifts slowly through the lives of its characters, swimming in observations of their actions that float in and out of the frame. Each insight, in turn, adds a piece to a huge puzzle of futility. Even though we can explain how and why each psychological response happens, we can't even begin to come up with a solution to the main problem at hand, which seems completely right.

As he did in his 2008 masterpiece, Still Walking, Koreeda has a poet's eye for the subtleties of people. In this movie, there are two scenes that are as well-observed as anything else he's ever done. Each of them uses a still photography motif that reminds me of Edward Yang's Yi Yi. In a heartbreaking scene near the end of the movie, Ryomo looks at the candid photos that Keita has taken with the family's digital camera for the first time. In doing so, he discovers a part of himself that he never knew existed. In another, the two families pose quickly for a group photo. The way the image is blocked shows not only the differences between the clans -- one is strict and austere, while the other is loose, emotional, and unrestricted -- but also the differences between traditional and more modern Japanese ideas of family.

3 notes

·

View notes