Text

Untuk Sebuah Dunia yang Memuat Banyak Dunia

Kepada kawan-kawan yang saya hormati dan kasihi,

Saya ingin mengucapkan terima kasih banyak atas proses yang kita lalui bersama- sama selama 4 bulan ini sebagai Solidaritas Pangan Jogja. Berada di Solidaritas Pangan Jogja, berada di antara kawan-kawan sekalian, mengajarkan saya banyak hal.

Saya belajar untuk mendengarkan.

Saya belajar untuk memperhatikan.

Saya belajar soal kepercayaan.

Yang terpenting adalah saya belajar untuk percaya pada kemungkinan.

Di tengah pandemi ini, saya menyaksikan bagaimana berbagai macam kemungkinan tumbuh dan berkembang.

Tidak ada yang pernah memberitahu bahwa sebuah jaringan dapur yang terdiri dari berbagai macam orang, dari berbagai latar belakang, di berbagai lokasi di Yogyakarta, dapat terwujud di masa di mana kita harus tetap di rumah dan menjaga jarak. Tidak ada yang tahu bahwa jaringan dapur ini akan mendapat bantuan sayur setiap bulan dari PPLP, paguyuban petani yang lahannya sedang dalam bahaya direbut tambang pasir besi. Tidak ada yang membayangkan bahwa akan ada kebun yang terus mengirimkan sayur ke orang-orang yang membutuhkan.

Solidaritas Pangan Jogja bekerja seperti kacamata bagi saya. Saya mampu melihat hal-hal yang sebelumnya tidak terlihat bagi saya. (Saya berhutang bagian refleksi ini pada proyek film seorang kawan)

Sebelumnya saya hanya bisa mengakses realitas atau kenyataan melalui apa yang saya lihat di internet diperantarai media sosial, apa yang terlihat di jalan raya atau ruang publik, tempat yang biasanya saya lewati. SPJ membawa saya memasuki rumah-rumah lain, gang sempit, jalanan yang tidak pernah saya lewati, kost/ kontrakan/asrama, sawah-sawah dan petani yang menggarap sawah-sawah tersebut, ruang pertemuan yang tersembunyi. Solidaritas menciptakan pertemuan di antara orang-orang yang kerap terlupakan karena keberadaannya tidak terlihat atau dianggap tiada oleh para pemangku kekuasaan.

Saya teringat sebuah kutipan dari sebuah rekaman diskusi antara dua akademisi yang membangun refleksi mengenai gerakan sosial, khususnya terkait perjuangan

melawan diskriminasi ras dan kelas di Amerika, yaitu Fred Moten dan Stefano Harney. Fred Moten mengatakan bahwa ada perbedaan antara empati dan solidaritas. Empati muncul dari kemampuan kita untuk melihat diri kita di orang lain. Ada diri kita di orang lain. Sedangkan solidaritas muncul dari ketiadaan diri “saya” di orang lain. Bukan persamaan yang dicari. Yang diakui adalah ada hal yang menghancurkan berbagai kehidupan. Hidup ini ambyar untuk saya. Ambyar untuk anda. Ambyar untuk mereka. Ambyar untuk kita. Solidaritas tidak melulu diawali dari hubungan antara keambyaran hidup kita semua karena memang banyak perbedaan. Tapi solidaritas memungkinkan kita untuk bertemu, menemukan perbedaan, membangun penghormatan atas perbedaan tersebut dan menciptakan hubungan yang menguatkan kita bersama agar berbagai jenis kehidupan dapat terus hidup.

Sebuah dunia di mana banyak dunia bisa muat. (ini adalah prinsip yang digaungkan pula oleh Zapatista, sebuah kelompok masyarakat yang mengelola wilayah otonom di Chiapas, Mexico)

Dunia yang sedang kita huni, dibangun tidak dalam nilai ini. Pembangunan yang marak kita saksikan justru menghancurkan banyak kehidupan. Terutama kehidupan yang hidup dari tanah, sawah, kebun, serta rumah-keluarga tanpa sekat. Para penguasa membangun kekuasaannya dengan memakan habis kehidupan- kehidupan lain dan membangun dunia yang hanya layak huni untuk mereka, para elit.

Solidaritas, di dalam dan yang sudah melampaui SPJ, adalah upaya untuk membangun dunia yang lain. Dunia di mana banyak dunia dapat muat. Setiap batu untuk membangun dunia baru ini, muncul dari hubungan-hubungan di tengah perbedaan dan persamaan. Setiap batu di dapat dari proses berjalan bersama- sama dan terus bertanya kepada satu sama lain. Dan semua ini dimungkinkan karena ada kepercayaan pada kemungkinan. Siapa saja bisa menyebut ini sebagai kemungkinan untuk pembangkangan yang militan, radikal, revolusioner atau apapun itu. Bagi saya, ini adalah ada bentuk penghormatan untuk berbagai kehidupan dan pembangkangan kepada kekuasaan yang sedang membunuh kita perlahan-lahan. (Refleksi mengenai solidaritas sebagai penghormatan saya dapatkan dari Mas Wid, PPLP)

Dalam solidaritas. Selalu.

Dina (salah satu admin Solidaritas Pangan Jogja)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seni Menambah Pekerjaan (2019)

“Ngapain yang mudah dibikin susah..”

“Buang-buang waktu aja..”

“Gitu aja kok repot..”

Daftar keluhan mengenai kesia-sian dalam proses dan waktu kerja dapat terus memanjang. Hal ini menandakan bahwa dalam hasrat kita semua, proses dan waktu kerja sebaiknya menjadi lebih cepat. Efisiensi tercapai jika hasil kerja pun bagus dan mampu mengganti biaya produksi dan melipatgandakan keuntungan. Yang penting cuan —begitu dalam ungkapan yang kerap digunakan hari ini.

Perwujudan dari hasrat ini adalah otomatisasi yang sudah marak di berbagai sektor industri. Otomatisasi tidak hanya terjadi di pabrik, sebagai penggantian tenaga manusia ke mesin. Proses otomatisasi pun terjadi di wilayah manajemen organisasi dan institusi. Beragam standar prosedur operasi dibuat untuk memperlancar (baca: mempercepat) kerja. Konflik dan gesekan antar manusia diminimalisir dengan relasi sosial yang teregulasi di lingkungan kerja. Kemelesetan sebisa mungkin ditekan.

Prioritas atas efisiensi juga dapat ditemukan dalam proses berkesenian. Ini bukan hanya soal menciptakan proses kerja yang cepat dengan untung berlipatganda. Berbagai unit kerja diciptakan dengan tugas memfasilitasi kelancaran dalam proses kerja Sang Seniman, mulai dari artisan, asisten, manajer, bendahara, hingga para pemagang. Sang Seniman menjadi sebuah unit pencipta gagasan yang kemudian akan dikirimkan ke unit-unit kerja lainnya —asisten, artisan, dsb— untuk diproses hingga menjadi karya seni. Ini adalah mesin produksi seni yang berjalan di skeitar kita. Tentu saja karya seni ini akan bernilai tinggi dan tidak mampu dimiliki oleh unit-unit kerja yang memproduksinya. Kondisi serupa terjadi di pabrik-pabrik yang memproduksi benda yang tidak dapat diakses pekerjanya, seperti smartphone.

Nilai dari karya seni diciptakan tidak semata-mata dari alih wujud material, tapi melalui proses kognitif dan afektif yang kemudian menjadi komoditas dan memfasilitasi proses akumulasi keuntungan di tangan tertentu —sebagai salah satu moda ekonomi kapitalis.

Ini semua bukan proses yang saklek dan pasti terjadi di mana pun. Moda kerja dan penciptaan nilai yang berbeda masih dapat ditemukan ketika seseorang melakukan apa yang tidak biasanya. Argumen saya: Doli sedang berada di patahan itu.

Saya berbincang dengan Doli di sebuah sore, di tengah kesibukannya dari dan menuju ArtJog. Walau sudah mengenal Doli selama 12 tahun, saya tidak terlalu mengetahui kabarnya atau perkembangan praktik artistiknya. Ketika saya tanya apa ia sedang mempersiapkan karyanya di ArtJog, ia menjawab tidak. Di ajang pasar seni terpopuler tersebut, Doli bertanggung jawab untuk Afdruk 56, sebuah kamar gelap mobile dari Ruang Mes 56. Bersama dengan Afdruk 56, Doli kerap kali membuat lokakarya untuk mencetak foto di kamar gelap.

Perbincangan kami pun berlanjut dengan penelusuran perkembangan praktik artistik Doli selama ini. Doli bercerita bahwa sebagai seniman, ia merasa karirnya berjalan sangat lambat. Semenjak dua anaknya lahir, Kemangi dan Serai, Doli bersama Ipiet, istrinya yang menjalankan bisnis busananya, harus membagi waktu antara mengurus anak, bekerja untuk mencukupi kebutuhan keluarga, dan terlibat dalam kolektif seni Ruang Mes 56. Hal-hal yang lazimnya terkait dengan pengembangan karier individu kesenimanan menjadi prioritas entah nomer berapa. Alhasil menurut Doli, salah satu implikasinya adalah ia jarang membuat pameran tunggal dan menyandang titel sebagai seniman yang tidak produktif.

Akantetapi Doli menggarisbawahi dua aspek penting dalam praktik artistiknya, yaitu kelambatan dan keintiman. Keintiman dibangun dengan membutuhkan banyak waktu dan kelambatan adalah motornya. Karya-karya Doli kerap melibatkan orang-orang di sekitarnya, sebagai obyek karya (misal seri Animal Mask Collection, 2009) maupun yang sekedar meminjamkan alat atau properti (seri Green Hypermarket, 2012). Hubungan dengan orang-orang di sekitarnya dan pertukaran gagasan di antaranya, tentu tidak dibangun dalam waktu yang singkat.

Dalam seri karya yang dipamerkan kali ini, Raw Power, Doli memperlihatkan nilai dari kelambatan dan keintiman sebagai teknik pengolahan material, bukan hanya moda penciptaan relasi sosial. Sejak beberapa tahun belakangan ini, Doli mulai memperhatikan alat yang digunakan oleh pekerja-pekerja di berbagai tempat di sekitarnya, mulai dari bengkel motor, bengkel kerja seniman, tukang kayu hingga dapur di sebuah restoran/ruang seni.

Bagi Doli, alat kerja diciptakan untuk membantu kerja tangan dengan segala keterbatasannya. Berbekal alat kerja, bahan-bahan mentah dapat diolah menjadi produk yang bernilai lebih tinggi. Produk kemudian akan dipasarkan, dibeli dan dikonsumsi. Sedangkan alat kerja tetap berada di tangan para pekerja yang kemudian memproduksi komoditas-komoditas selanjutnya. Doli meminjam alat-alat dari tangan para pekerja dan melakukan studi material atas benda tersebut. Studi dilakukan dengan menjadikan alat kerja sebagai obyek untuk proses fotogram. Dalam proses fotogram, obyek diletakkan di atas kertas yang peka cahaya, lalu disinari dan diproses dengan cairan kimia. Hasil dari proses ini adalah siluet benda-benda ini dalam warna putih dengan hitam sebagai latar belakangnya. Kemelesetan adalah kondisi material di mana kontrol manusia menemukan batasnya.

Walau terdengar sederhana, proses penciptaan komposisi dalam fotogram memakan banyak waktu di kamar gelap dan terbatas hanya pada bidang kertas 3R (8,9 x 12,7 cm). Kesempurnaan yang mutlak sesuai dengan harapan si pencipta, harus terus dinegosiasikan dengan kondisi material. Komposisi gambar yang besar dalam fotogram dibuat dengan menyusun dan menggabungkan kertas-kertas 3R. Hasil penggabungan ini tidak dapat “sempurna” karena dilakukan di dalam kamar gelap. Alhasil ada jejak garis putih di antara kertas-kertas yang digabungkan. Jenis material yang tersedia untuk teknik fotogram pun terbatas, sehingga kualitas gambar fotogram tidak dapat sehalus hasil cetak digital.

Di tengah keterbatasan material ini, Doli tetap gigih untuk terus menggunakan teknik fotogram. Kenapa ini disebut kegigihan? Teknologi kamera semakin canggih. Resolusi foto yang dihasilkan memiliki kejernihan dan detail yang tinggi hingga menyerupai realitas, bahkan menjadi realitas baru. Proses cetak pun semakin cepat dan murah. Lalu apa pentingnya melakukan fotogram di masa sekarang? Mengapa harus melihat foto siluet alat-alat kerja ketika di internet kita dapat menemukan foto berwarna dengan resolusi tinggi dari obyek tersebut?

Doli percaya pada potensi produksi pengetahuan baru dengan kembali berkutat pada teknologi “purba” fotografi macam fotogram. Teknologi digital tidak menggantikan analog. Keduanya justru berjalan beriringan dan menyuguhkan nilai yang berbeda satu sama lain. Fotogram merupakan satu metode untuk mempelajari obyek melalui bayangan dan kontur.

Dalam proses produksi seri Raw Power, Doli menghabiskan banyak waktu dengan alat-alat kerja ini, untuk menangkap bayangan, mempertegas bentuk, dan menampilkan kreativitas para pekerja melalui alat-alat kerja yang mereka ciptakan. Contohnya di satu gambar, kita bisa menemukan sebuah alat dengan palu di satu ujung dan kunci inggris di ujung lainnya.

Di tangan pemiliknya, benda-benda ini mungkin dengan mudah digeletakkan di lantai atau diganti dengan yang baru ketika sudah rusak. Namun di tangan Doli, alat-alat kerja ini diperlakukan dengan hati-hati dan ditata satu persatu. Menurut Doli, ada keintiman antara alat-alat kerja ini sebagai obyek fotogram dengan dirinya sebagai pencipta.

Beragam alat masak bersanding dengan alat cukil, alat lukis, dan alat bengkel. Sekilas tidak ada yang menghubungkan benda-benda ini, terkecuali bahwa mereka adalah alat kerja. Mereka berasal dari proses kerja yang berbeda-beda. Tapi dengan melihat alat-alat ini dalam komposisi yang sama, sebuah kondisi pun muncul ke permukaan dan tersuguh di hadapan kita. Di masa yang didaulat sebagai era ekonomi perngetahuan, kerja berbasis material tetap menjadi tulang punggung kerja imaterial walau kerap kali ia tidak terlihat karena dikerjakan di ruang tersembunyi seperti dapur atau bengkel. Kerja-kerja ini pun dilakukan oleh para tukang, yang disebut hanya menjalankan perintah (baca: ide) dari atasannya.

Namun seperti kepercayaan pada potensi pengetahuan dalam proses penciptaan foto yang lambat dan purba seperti fotogram, Doli pun meyakini ada sesuatu yang tersimpan dalam alat-alat kerja dan kisah para pekerja yang menggunakannya. Sesuatu itu mungkin adalah soal siasat untuk mengatasi keterbatasan atau mempersoalkan mengapa kerja material kerap dianggap rendahan. Mungkin ini juga soal mengembangkan praktik artistik yang tidak melulu soal karir, kecepatan, atau kesuksesan. Ini soal pengembangan praktik sebagai sesuatu yang terus menerus dilakukan, melalui keterhubungan dengan orang sekitar dalam cara yang tidak biasanya (meminjam alat, bicara soal kerja).

Doli berkata bahwa ia akan terus berbicara dengan para pekerja, meminjam alat kerja mereka dan mengabadikannya dalam teknik fotogram. Entah apa yang akan didapatkannya. Yang pasti ini soal melihat ke tempat-tempat yang jarang dilihat, menemukan batasan atas apa yang bisa dilihat, dan menemukan berbagai keterhubungan baru. Inilah seninya menambah-nambah pekerjaan, seperti yang Doli sedang lakukan.

1 note

·

View note

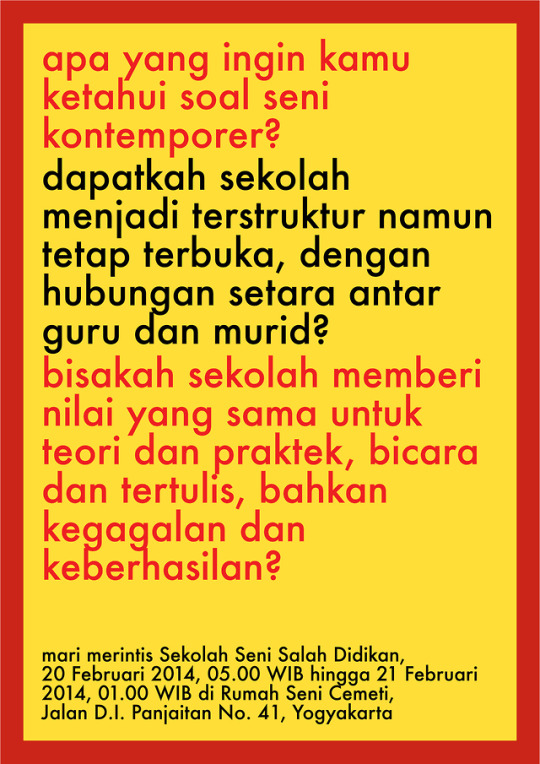

Photo

Dalam serangkaian kelas yang berlangsung selama 17 jam pada 20 Februari 2014, Sekolah Seni Salah Didikan merumuskan gagasan mengenai fungsi ruang seni seperti Rumah Seni Cemeti dalam pendidikan seni alternatif di Yogyakarta. Kursi-kursi ini merupakan rekam jejak atas pembicaraan tersebut. Sekolah Seni Salah Didikan adalah sebuah tempat yang dibentuk oleh berbagai upaya mendidik diri sendiri, termasuk di dalamnya praktik mencipta, membagi, memperbaiki, mengganti dan menerima pengetahuan, secara bersama-sama dan dalam hubungan setara.

In the series of classes that took place for 17 hours in 20 February 2014, Sekolah Seni Salah Didikan formulated a notion regarding the role of art spaces such as Cemeti Art House in the context of alternative education in Yogyakarta. These chairs serve as track records of the discussion that arose during that time. Sekolah Seni Salah Didikan is a place formed by various attempts at self-education, including processes of creating, sharing, improving, changing and receiving knowledge, as a collective and within a relationship of equals.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

In the end, however, as Saidiya Hartman says, “the right to obscurity must be respected.” This is a political imperative that infuses the unfinished project of emancipation as well as any number of other transitions or crossings in progress. It corresponds to the need for the fugitive, the immigrant and the new (and newly constrained) citizen to hold something in reserve, to keep a secret. The history of Afro-diasporic art, especially music, is, it seems to me, the history of the keeping of this secret even in the midst of its intensely public and highly commodified dissemination. These secrets are relayed and miscommunicated, misheard, and overheard, often all at once, in words and in the bending of words, in whispers and screams, in broken sentences, in the names of people you’ll never know. (p. 105).

Fred Moten in B.Jenkins (source)

0 notes

Text

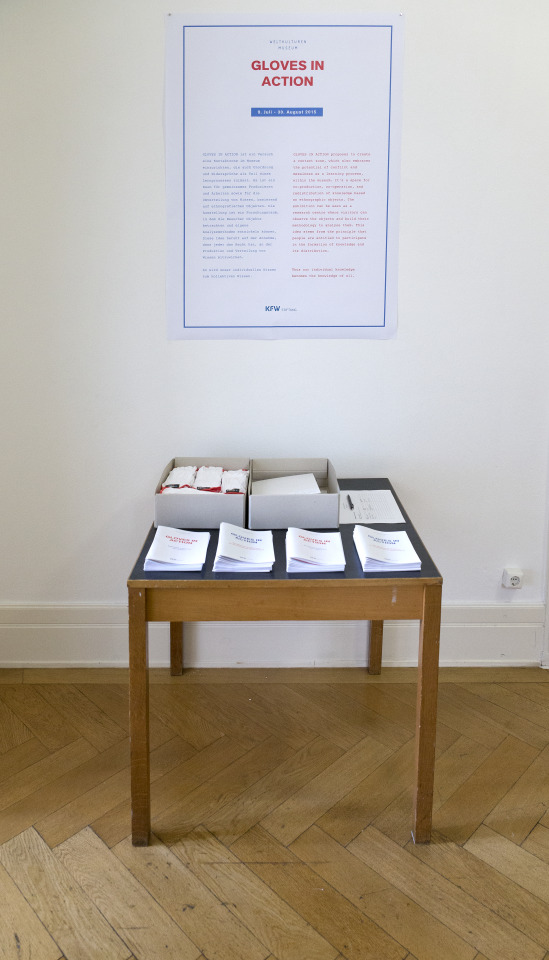

What to Unlearn from Art Organization (2018)

Essay for Annette Krauss’s work in Shapes of Knowledge exhibition publication for Monash University Museum of Art

Part 1: The Double Binds of Cleaning, from Collective Empowerment to a Form of Mobilised Labour

I would like to start this text by recalling a conversation that I had with friends and colleagues – including Antariksa, Brigitta Isabella and Ferdiansyah Thajib (KUNCI, Yogyakarta), Binna Choi (Casco Art Institute, Utrecht) and Emily Pethick (then director of The Showroom, London) – at a public event in January 2015 at KUNCI’s office. The conversation was transcribed into a text entitled ‘Toilet Tissue and Other Formless Organisational Matters’. In this conversation, we were talking about the organisational practices of different institutions and their relations to common struggles, such as the fights against capitalism, patriarchy, normativeness and inequality, or the struggle for commons. As goofy as the title might seem, it came from my complaint about how often I had to buy toilet paper for the KUNCI office and how I wish I could have done more ‘productive’ work instead of buying toilet paper.

This event was announced publicly with the title ‘Curating Organisations (Without) Form’. For the announcement, we used an image of the Casco team emptying few buckets of dirty water in front of Casco office, as part of a collective exercise which the Casco team did with Annette Krauss as part of the project Site for Unlearning (Art Organisation). Later I would learn that this collective cleaning exercise is aiming to unlearn organisational practices, so that participants can see how reproductive labour is undervalued and the inequalities in the division of labour – including how reproductive labour is always the last priority in an institutional setting.

However, when I first saw this image my memory turned to my elementary school days. I went to an elementary public school in West Java, Indonesia. The total number of students, from first to sixth grade, was five hundred, yet the school had only nine classes, so we had to take turns in using the classroom by splitting the school into morning and afternoon classes. The morning classes were for first, second, and sixth graders, while the afternoon classes were for third, fourth, and fifth graders. It was the responsibility for the morning classes, especially the sixth graders, to clean the classrooms before school started. The teacher would always remind us that it was our duty as students to take care of the school, as much as we would take care our own houses. It was our shared responsibility to take care our house: the school. Another reason was that because the school could only employ one person as the school caretaker, we should help him as well.

In my assigned day to clean, I would come to the school early with two of my friends. We would clean our class before the lessons started. Sometimes I brought cleaning products from home to clean the class. After mopping the floor, we would throw the remaining dirty water in front of our classroom. The reason was because my school had an odd plumbing system. The school building was in a shape of a square with classrooms facing of each other, a garden in the centre and a gutter surrounding it. The dirty water from class-cleaning sessions would be disposed of in the gutter. Since the gutter was located in the centre of the building, everyone could see when someone had disposed of the dirty water.

Ever since I graduated from this elementary school, I have never done any cleaning task in school. I continued my study from middle to high school in a private Catholic education institution. This school was more expensive than my elementary school, and employed more than twenty workers to clean around thirty classes. The student’s task was only to study and to be polite with the school workers.

The maintenance of the school is the job of the workers, not the students. Without being aware of it, at that moment I entered an institutional setting where the division of labour was firmly implemented. Work is not only a definition of what we have done but becomes how we identify ourselves and each other. The social identification based on work even goes further – to spatial arrangements. The students could be easily seen everywhere around the school buildings, while the cleaners had their own areas. The cleaners tried to make themselves invisible. No one saw the cleaners while they were emptying the buckets of dirty water. Cleaning is work that is kept out of public eye.

Cleaning is part of the unlearning exercise which was developed by Annette Krauss and the team at Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons, a mid-scale contemporary art organisation in Utrecht, The Netherlands, for the project Site for Unlearning (Art Organisation). The project comes from the shared pursuit to unlearn institutional habits through an investigation into the schemes of productivity that drive art organisations.

As part of the exercise, every Monday the Casco team members clean the office together. From their reflection upon this exercise, the team felt the power of cleaning together as collective effort. It was important to do cleaning together, instead of delegating this labour to interns or outsourced labourers, as a way to study reproductive labour in an art institution setting.

In comparison, in my elementary school experience, cleaning was framed as part of the student responsibility partly because the school decided to employ only one person as the cleaner for the whole building. The student’s collective effort was mobilised and used by the school to avoid spending funds on an additional cleaner’s salary. To clean the school together was also framed as an exercise of gotong royong, a form of mobilising labour through discourse and collective work. Gotong royong, which can be translated as ‘mutual assistance’, was and still is being promoted as part of Indonesia’s identity. It takes many forms, from collective kitchens to self-organised processes of building houses, although, as anthropologist John R. Bowen has mentioned, in certain forms of gotong royong, the mutual assistance of members of the community can start to feel like unpaid labour. For example, the repairing of a drainage system in a neighbourhood could appear as ‘assistance’ but begins to resemble corvée when it is commandeered by a local official for the construction of a district road.

A few years ago, on a main road in Jogja, I saw a public-service billboard announcing: ‘Mari gotong royong membayar pajak untuk Indonesia’ (‘Let’s gotong royong in paying tax for Indonesia’). There is no mutual assistance in paying tax. The message was to bring people together to pay tax without using commanding words.

In Site for Unlearning (Art Organisation) the cleaning exercise is a form of study about how collectively we can empower each other by doing reproductive labour together. The definition of study that I would like to emphasise is an important concept in this project – study as something we do with others in order to escape while finding commonalities. Collective cleaning as study means that it is being done together as the participants look for connections with each other while taking refuge from the measuring of productivity in the workplace. This conception of study has resonance with what Stefano Harney and Fred Moten (2013) describe as ‘fugitive planning’– study as something you do with others while being fugitive from the dominant values.

Meanwhile, collective cleaning, along with other forms of communal reproductive work, can serve the purpose that it resists and become a means for control instead of empowerment. This is what happened with gotong royong in the Indonesian context. The mobilisation of gotong royong or any form of mutual assistance has become part of the way governing bodies establish harmony within the society to enable the power and control of the state.

Harmony and governance have a specific entanglement in the Indonesia context, related to the writings of early nationalist thinkers of Javanese cultural background. An Indonesia nationalist thinker, Soetomo (1888–1938), for example, wrote about the ‘gamelan society’, in which

… rakyat beruntung jika mereka bekerja sama secara serasi dalam memainkan gamelan, di mana bukan hanya mereka yang bersangkutan yang mesti tahu bagaimana memainkan dan menjadi mahir dalam suatu alat musik, mereka juga mesti manut (mengikuti) peraturan-peraturan dan menaati hukum.

… the society is fortunate if they work together in harmony in playing gamelan, when those who hold the instrument also know how to play it and become good at it, yet they also need to obey the rules and law.

This is one of the double-binds in collective reproductive work. While it offers a form of being and doing together that has been undervalued by the dominant capitalist logic through attribution of work according to gender, race, class, physical abilities and more, collectivity in all forms of work, both productive and reproductive, can also be mobilised and utilised to enable control by a specific group in power: state, employers or others. The double-bind could and will never be resolved, since we are living in a multiple condition full of contradictions. Yet what we can do is play the double-bind by composing different modes of governing ourselves that remain critical about what is considered ‘work’.

Part 2: New Modes of Governing Ourselves

I am part of KUNCI, as a member. Oftentimes I introduce myself as someone who works in KUNCI, although I do not define KUNCI as merely my workplace. It is also something else.

KUNCI was established in 1999, a year after the end of New Order era in Indonesia (the Soeharto era). Nuraini Juliastuti and Antariksa co-founded KUNCI in the spirit of producing critical knowledge through different platforms and activities. Both of them were involved in the student and civic movements which had succeeded in overthrowing Soeharto from his thirty-two years of dictatorship in 1998.

After 1998, other ‘alternative spaces’ emerged alongside with KUNCI, including ruangrupa (Jakarta, 2000), Forum Lenteng (Jakarta, 2003), Ruang MES 56 (Jogjakarta, 2002). ‘Alternative space’ is a particularly well-known phrase within the environment of art and cultural organisations in Jakarta, Bandung, and Yogyakarta. Alternative spaces have been playing key roles in different cultural practices. Now, citizen initiatives in the cultural field suggested by ‘alternative space’ also flourish in other locations such as Surabaya, Jatiwangi, Aceh and Makassar, using new methodologies for cultural activities based on the communities in which they are located.

None of these spaces started in a formal institutional setting such as an office, museum, or gallery, but rather in home settings – either a shared house or a member’s house. KUNCI, including the library, moved from one member’s dormitory room to the living room of another member, to a publisher’s garage, to a shared house with Ruang MES 56, until finally it was able to rent a house in 2011.

When I started to come to KUNCI regularly, I didn’t consider it as part of my work. I was a volunteer for the library. My task was to open and close the library according to its public hours. There was no payment for my work. My ‘salary’ was to use the internet freely. As I was (and still am) an avid internet browser, this ‘salary’ was decent enough. After hanging around for some time, I started to come to the KUNCI library more often, even outside its public hours. I read, discussed, ate, cooked, and sometimes also slept in the library. KUNCI was slowly becoming my second home. Later on, my relationship with KUNCI was formalised when I received my first salary in 2010. Since then I have been working at KUNCI, yet I feel also at home there.

Ade Darmawan, co-founder of ruangrupa, has mentioned the domesticity of alternative spaces in Indonesia because of their house settings and the friendship networks. Although in early 2000 many art and other organisations started registering themselves legally and used the prescribed organisational structures – director, manager, accountant and board as required by the government to enable them to receive financial support from international funding agencies – within these formal bodies, the spirit of friendship and informality still exists.

KUNCI is still in a state in between. It was started as circle of friends. Then as we expanded our activities and they became larger and longer, we also got grants and funding that required us to be more formally accountable. So then we employed a director, a program manager, a finance person, and so on. But with this division of work, we also became more professionalised, with more specified functions for each person, so they do only the work that is assigned to them. The caring of the space became work for the cleaner, librarian and intern. Then, in 2013, we decided to get rid of the formal structure and make (almost) everyone a member of KUNCI. So today everyone is a co-director and everyone is a member. And it’s still a challenge to practice this form. Today we consist of nine members.

In the shared spirit of Site of Unlearning, by constantly challenging the way we work in our organisation we are trying to be more aware of the work of knowledge production and the kind of work that enables this knowledge production to take place. The kind of work which involves cleaning, buying toilet paper, listening to complaints, giving encouraging words. It is a work which serve life, not commodity production. It is a reproductive work, which also a terrain for political struggle. As activist and scholar Silvia Federici wrote, ‘On the positive side, the discovery of reproductive work has made it possible to understand that capitalist production relies on the production of a particular type of worker, and therefore a particular type of family, sexuality, procreation, and thus to redefine the private sphere as a sphere of relations of production and a terrain of anti-capitalist struggle.’

By trying not to outsource this reproductive work to other women, interns and assistants, and by dividing the responsibilities equally among members (or friends), we become aware that we are indebted to each other for the work we’ve done. Defining (alternative) ways of organising and of becoming institutionalised is an important cultural project, which can serve as a site for knowledge production that is grounded in the political struggle.

Part 3: Exercising as the Refusal to Work

Annette Krauss and the team at Casco have been developing different exercises in order to unlearn institutional habits. Cleaning is only one part of the whole set of exercises. The other exercises are related to meeting, reading, care network, property, wage and well-being, authorship, time, passions and obstacles.

The ‘unlearning exercises’ take various amounts of time. For example, the ‘Off-Balancing Chairs’ exercise lasts according to how long the meeting participants can hold their positions in a set of wobbly chairs to unlearn meeting habits. The ‘Time Diary’ exercise requires everyone to record their day for a limited period of time – from a few days to weeks. Besides doing these exercises, the participants also need to work as usual, from replying to emails, writing and editing, to organising events. I wonder if doing these exercises adds more work to the already existing work for the team at Casco. Why would they do all of these exercises? Would it be more useful for team at Casco to spend time in writing text about reproductive works rather than cleaning?

I would argue that the strength of these exercises lies on how they successfully suspend the team members at Casco from their ‘real’ work. It creates ruptures in organisational work and this relates to the struggle against work. It is also a form of escaping while finding different connections. As feminist scholar Kathi Weeks puts it, the problem with work is that it dominates our lives and it shapes the way we connect with each other. Work become the source of our social identification, both in and out of workplace. We even introduce ourselves by name and profession.

The Site for Unlearning (Art Organization) is a space to identify the self and each other outside of work categories within an institutional setting. We are not valuing each other based on what the other is being paid to do, but on what is possibly coming out of our different forms of togetherness. It is a form of alternative world-building through collective practices, one exercise at a time.

References

Open Engagement, In Conversation: Pittsburgh 2015 – Place and Revolution, http://openengagement.info/curating-organisations-without-form/.

John R. Bowen, ‘On the Political Construction of Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia,’ The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 45, no. 3, May 1986, p.548.

Savitri Prastiti Scherer, Keselarasan dan Kejanggalan, translation from ‘Harmony and Dissonance; Early Nationalist Thought in Java’, MA thesis, Cornell University, 1975, Sinar Harapan, Jakarta, 1985, p.241.

Silvia Federici, ‘The reproduction of labour-power in the global economy, Marxist theory and the unfinished feminist revolution’, 2009, paper for seminar The Crisis of Social Reproduction and Feminist Struggle, https://caringlabor.wordpress.com/2010/10/25/silvia-federici-the-reproduction-of-labour-power-in-the-global-economy-marxist-theory-and-the-unfinished-feminist-revolution/.

Kathi Weeks, The Problem with Works: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2011.

0 notes

Text

A call for alliances between islands (2017)

This text is partly consist of script for my Fantasy Island exhibition tour and the other parts were taken from my fieldwork notes during my 2 months stay in Batam Island, in 2010.

I remember there’s a big cruise ship in the parking lot of Nagoya shopping complex. The cruise ship is attach to part of the mall and I can remember although vaguely that the ship was actually a restaurant. Around Nagoya shopping complex, there are few ports which offer ferry services mainly to Singapore. I’m currently referring to Nagoya in Batam, Indonesia, not the Nagoya in Japan.

No one can tell when I was there in 2010, why there’s a shopping complex in Batam, named after a city in Japan. Not far from Nagoya shopping complex, I found a mall called Lucky Plaza which reminds me of the Lucky Plaza in Singapore. In Batam Lucky Plaza, I bought a cell phone with Thai letters inscribed to its keypad.

Batam is a city where things are often out of sync with each other although they are part of the same environment. Yet this situation is not typically Batam. As much as Singapore goverment wants everything to be in its designated place, it’s a matter of careful notice to find odd gestures and unsual movements of bodies and objects.

Fantasy Island is stated as an exhibition about a relation of two islands, which are Singapore and Batam. Although one can’t help to think that this project can be seen also as an exhibition about Batam which is being held in Singapore. A place is currently being represented in another place.

I think there’s a heavy burden which this exhibition is facing. Perhaps also suffering from. The burden of staying true to the experience of being there (Batam) in here (Singapore). Adding to that, is also the delicate task on representing inequalities within the relations of Batam and Singapore while being aware of the trivializing trap.

This is not the burden which suffered by this work alone. This is a condition which James Clifford address when he criticize how field research is obsessed with the act of dwelling. The longer someone stays the more s/he possessed the local authenticity. Therefore, the ideal ethnographer is someone who travels, then stays and writes. The native is the one who borns and lives there. The ethnographer will try to capture and possess as much localities as the native. The native doesn’t need to do anything. A passive-active relation, the subject-object, the one who represent and being represented.

Representation is a totalizing relation. It’s always either this or that. As if there’s no other way of being and doing things.

Therefore iI would like to refuse the logic of representation. Rather than thinking about the “realities” in the field (there, in Batam) which each of this work is trying to conveyed (here, in Singapore), I would like to discuss how these works, the environment of Batam, and Singapore are part of surfaces of our life which are being hold together by various sets of technologies.

Technology as our mode of being in this world. This allows us to have a holistic approach on body as not separated from the environment. By shifting our attention to the technologies which holds together the surface of our life (with human and environment as one), various typologies of relations might start to emerge. That relations are not always totalizing, such as conqueror and being conquered.

Again it’s the art of noticing. What happen in places that often being ignored where the intricate web in which values and affects are constantly moving and overlapping?

When I was visiting Batam, I had to use taxi as my main transportation mode within the city of Batam. Although there are other forms of public transportation, such as bus, but the coverage area wasn’t broad enough. The type of taxi which I had been using in Batam wasn’t an “official” taxi. It’s a regular car, without official license plate for public transportation and instead of using meter, the cost is decided based on agreement with the driver. Every taxi driver I met always asked if I was in Batam for work or temporary visit. When they found out that I’m a visitor, they would give me their cellphone number and asked me to call them whenever I need a ride.

That’s how I met Arief. Arief is a taxi driver who came from West Sumatera Province like most of taxi drivers in Batam. Batam is perceived as the right place to get a job with more than decent payment. This condition was cause by its proximity to Singapore. According to Arief, Batam is the gateway for Indonesians to find job in Singapore or at least to get money from Singaporean without having to leave Indonesia just like what he do. Arief had few regular clients and all of them are Singaporeans who went to Batam to get things or services which they couldn’t have back in their homeland. One time, Arief took a Singaporean middle-age woman who came to Batam only to buy thirty cans of powder baby milk. It’s also a commons sighting for Arief to see foreigners whom he suspected to be Singaporeans, to buy instant noodles or other daily needs products in bulks in Batam and brought it back to Singapore by ferry.

He said everything in Batam is much cheaper than Singapore, although he’s never been to Singapore. So he can understand if Singaporeans prefer to do their grocery shopping in Batam. On top of that, according to Arief, the Singaporeans are generous tipper in comparison to Indonesians or Malaysians.

As I look into Evelyn Pritt’s photography work on abandoned buildings in Batam, my mind goes back to the memories of empty shops, malls, and houses which I had encountered during my stay there. These signs of decay made me think of Batam as a place of ruins —ruins of speculative development, as Evelyn Pritt mentioned in her statement. One of the moment in Batam which amplified this thinking, was my visit to the ruins of BIP Mall. BIP Mall was an active shopping center in 2004 until it was being closed down in 2006. I didn’t find any sufficient information on what leads to the closure of this mall. Arief told me that perhaps the developer company went bankrupt.

Yet ruins are not a condition without life. There are many forms of living which can emerge in between ruins. The empty malls is a place for local teenager in Batam to practice skateboard, inline skate, or even refined their paint spray can techniques. Evelyn found few bottles of wines which looked quite recent in one of the abandoned houses.

The precariety of living in Batam —where investments can fail, young people are jumping from one job to another, becoming outsource labour for companies abroad— exist side by side with the freedom of having fun according to one’s needs. Sex tourism is one the popular image which Batam has been associated with. Once enters the realm of commodification, desire is the previlege of clients (predominantly male with money) to be fulfilled, which Ardi Gunawan’s work had proposed to be subverted. Batam is the place to seek economical refuge for Indonesian. While at the same time, according to Arief the taxi driver, Batam can offer what Singaporeans couldn’t get in their homecountry, which is to have fun. Batam is a place to seek refuge from the psychic repression of Singapore.

Batam was built to become the Indonesia version of Singapore, through president’s decree, Keppres No, 41 Tahun 1971 which is also an important reference in Eldwin Pradipta’s work. These two islands are not separated entities. They are being developed in mirror to each other, benefiting the one with more power (wealth) over the powerless. If states are in alliance with each other, should sovereignity simultaneously also being built within the non-state realm in order to resist the totalizing power? How to put desire, as the urge which moves between two islands, as political means?

I would like to conclude this text with emphasizing us and the environment as one surface where we depend on each other in order to exist. The fact that we need each other to survive means that non-state alliance between island is possible. Then the further question would be, what can be the ground for this alliance? ila’s work puts a good metaphor on how struggle is similar to objects which are being swept away or left behind on the shore by tides. Resilience as the ability, not only to keep existing, but the improvisational moves along with time and tides of changes. Or like Wu Jun Han’s work which keeps breaking apart during the period of Fanstasy Island exhibition, precariety is the mark of our current existance.

Can precariety become the ground for non-state alliances between islands?

0 notes

Text

What’s left to learn in ruins? (2017)

An essay for On Curating Journal, February 2017

“I don’t think I can speak about the role of curating in extreme situations. I wasn’t in Christchurch when the earthquake happened in 2011. I have never experienced any natural disaster, armed conflict or other political turmoil.”

This comment was mentioned by one attendee during a roundtable discussion in Curating Under Pressure symposium. I couldn’t remember the topic of the roundtable discussion or the afterward discussions. But the comment stayed in my mind when I travelled back to Indonesia and even until now, two years after the conference was held in Christchurch, New Zealand. The reason why this comment left such a deep impression on me because it had revealed fundamental questions which the symposium had left open. Does extreme situation only limited to natural disaster and political conflict? What other condition can be categorized into extreme situation? How does this situation emerge and operate? What shall we do in this situation?

The Curating Under Pressure symposium had described the cause of extreme situation as natural disasters, extreme political pressure, oppressive regime or terrorist threats. During the symposium, extreme conditions were being addressed alternately with other terms, such as disaster, pressure, conflict and crisis. Despite the differences of vocabulary by speakers from various practices with geographically dispersed background, I can grasp the shared symptom of extreme situation as a moment of trouble, difficulty, and danger. It’s a moment for turning points where live as we know it had ended.

When Merapi Volcano erupted on November 5th, 2010 in Yogyakarta province where I’ve been living for 11 years, for few weeks both local and national media were flooded with news regarding to the disaster. Every day we heard updates on the scale of destruction and number of casualty caused by the volcanic eruption. On the ground, besides support from government, many civil groups organized emergency shelter with food and basic necessities supply for affected communities. In national television, academics and policy maker were in discussion on how to mitigate in post-disaster situation. Disaster mitigation is being framed as a stabilization attempt to recover back to normal.

In few months, the national media had stopped reporting anything related to this disaster. The news then filled with other major events, such as plane crash in West Papua, bomb terror, earthquake and tsunami in Japan, to the Arab Spring. And the life in Yogyakarta has never feel stable or “normal”. Not because the amount of destruction caused by volcano eruption was severe. Because living itself becomes increasingly uncertain and precarious in Yogyakarta and elsewhere.

The 2010 Merapi Volcano eruption was not the only natural disaster in Yogyakarta. In 2006, a 5,9 Richter Scale hit the southern area of Yogyakarta. It caused damage to more than 500.000 houses with 45.000 injured victims and 5744 people were died. According to data from National Disaster Management Authority (Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana, BNPB) website, various types of disaster had occurred across regions in Indonesia such as flood, landslide, earthquake, tsunami, fire, to armed conflict, terrorism attack and transportation accident. These are disasters which happened also in other parts of the world. This is what I meant by precarious living as a condition of getting by each day, from one trouble to another. It’s a matter of surviving.

Another type of disaster which is not listed in the BNPB website, is economy crisis. Ever since Indonesia was hit by economy crisis in 1998, around the period of Asia financial crisis in 1997, the economic condition is far from stable. It’s still the main task of Bank Indonesia to normalize the national monetary condition, especially after the 2008 global financial crisis. Austerity policies are being imposed globally. Basic necessities such as food, housing and education become increasingly expensive. Yet there are no significant raise on wages while welfare infrastructure become privatized. Workforce is being changed through subcontracting, outsourcing, with the rise number of part-time, temporary, self-employed, and home-based workers. The means of production are in the hand of these workers, yet the wealth gap between labor provider and capital owner are wider than ever.

“Let’s go and find a shaman to save our crops.”

“[But) no matter how many millions we spend on a shaman, if the climate stays like this, we’re done!”

The Land Beneath the Fog, directed by Shalahuddin Siregar in 2011, is a film which follows the life of families in Genikan, a remote mountain village on the slope of Merbabu Mountain, Central Java province, Indonesia. Both men and women of the families, are working as farmer who use Javanese calendar system to decide when to plant and harvest carrots, potatoes, and cabbages. But many things are changing around them. The climate becomes unpredictable. The rainy season is longer and the dry season comes late with unbearable heat. Their knowledge on nature becomes obsolete. The potatoes are rotting because too much rain. The tomatoes are dying from lack of water.

While the farmers are trying to save their crops, another life struggle has emerge. Arifin, the youngest son of one local farmer couple, Gunanto and Karni, just graduated from elementary school with the highest score. Although how much Arifin wants to continue to public junior high school, but Gunanto couldn’t afford to pay for monthly tuition and uniform cost. The only possible option is to send Arifin to Islamic Boarding School because it’s much cheaper. But his money is still not enough because the harvest is failing and he can’t find any job as outsource farming labor. So he went around the village to borrow money from his neighbors. In one scene, while contemplating on how to get money for Arifin’s education, he said “We still have neighbors who can help us out,”. Yet turns out, life is also not easy for everyone. “It’s hard to find a loan at the moment because nobody can predict their income,” according to one of his neighbor.

All crisis are operating in connection to each other. In the case of families in Genikan village, their life struggles are related to climate change, the selling price of vegetables from farmers are governed by free market mechanism, to lack of support for education. The texture of our living condition nowadays consist of intricate relations between moments of crisis and the ruins which the decreased crisis had left behind.

When I stayed in Berlin for 1,5 months last year, I’ve encountered conversations regarding to refugee crisis in Germany. With the constant stream of refugee coming to Europe, especially Germany, the opinions which circulated are torn between acceptance and preparing the necessary facilities to support refugees or blame them for development failure to terrorist attack. The myth of the stable first world and the uncertain third world become irrelevant. Precariety is a living condition which we have experienced globally in various scales and realm.

I’ve been reading The Mushroom at the End of the World, a book by Anna Tsing (2015). One of my admiration for this book, is on Tsing’s elaboration about how indeterminacy makes life possible and what does it mean to survive, through learning from mushrooms. Tsing wrote one of her encounter with two mushroom pickers, one of whom was a Mien from the hills of Laos who had come to the United States from a refugee camp in Thailand in the 1980s. Tsing met them when they were on the way to pick mushrooms in a ruined Oregon industrial forest. Another interesting story was the one which Tsing had heard from a Chinese matsutake trader: “when Hiroshima was destroyed by an atomic bomb in 1945, it is said, the first living thing to emerge from the blasted landscape was a matsutake mushroom”.

From these stories, I’ve learned how much humans and nonhumans, such as mushrooms, are a resilience being. Ruins are not the sign of death where life is no longer present. With the resilience which we are all embodied, ruins are the site for another forms of life to emerge. How can we expand our imagination on living in between ruins? In this attempt, it is also important to consider crisis not as an exception of how the world works or something which suddenly appears out of nothing. Crisis is revealing, not merely provoking. As in refugee crisis according to Didier Fassin, it is revealed that there is a long-standing distrust and hostility in Europe toward non-Europeans fleeing persecution and violence.

In search of action —what we can do together, how we can expand our imagination on living precariously, in between crisis and ruins— I would like to return to what Anna Tsing had learned from and about the mushrooms. Mushrooms exist in codependence. It needs other thing in order to live, such as trees. They live through collaboration along the encounters, while constantly changing with circumstances as a matter of surviving. “Purity is not an option.” Furthermore, Tsing elaborated that what we need to survive is a livable collaboration, not by fighting others.

The closest example to livable collaboration which I can think of for now, is in the statement of Gunanto about neighbor in The Land Beneath the Fog film. Although everyone in the village of Genikan are experiencing uncertainty in their income but there’s still a belief that they can help each other. In Gunanto’s experience, he did receive a loan from one of his neighbor, Sudardi and Muryati, for Arifin’s education. Despite the loan only covered 70% from the necessary cost. In another scene, the male farmers, including Gunanto and Sudardi, gathered and discussed whether they should invest together and start cultivating mushrooms. Unfortunately, none of them has access to money for investment. Still, I found it very important that they gather to talk about their life struggle and how to overcome it together. Livable collaboration involves the practice of caring on collective well-being.

What about in the realm of art and curating? What we can do through art in the condition of precarious living, in the times of crisis? I believe the attempt should lies on how we work rather than what kind of work to produce. It’s a call to rethink our ethics as curator, artist, intellectual, as well as human being. At the end, it’s not only related to work ethics but also life ethics.

I’ve been visiting a community who lives in one riverbank area of Yogyakarta without legal ownership certificate of their home and property. According to the law, they are a community of illegal settlers. Yet by operating outside the law, they created their own way of organizing. I’m deeply interested on how they organize property ownership. If anyone come to the community and want to stay in the land, then they will discuss it together. In some cases, when the person/family is allowed to stay, the community will help in building the houses.

I organized events with artists and the community such as workshops, film screening, with topics such as property rights, land ownership or community history as part of KUNCI’s projects. Few artists who worked there, had managed to establish personal relationship with the community. Yet my relation with them are still stuck in professional level. Whenever I came to their area, they always asked whether I have new projects to do there. I wonder if this happens because when I met them the first time, I introduced myself as a curator. Does curator always work from one project to another project? When the project ends, does the relation also ends? How to establish relation without the pre-assumption of output? How to be friends and not stuck in relation of participant-curator-artist?

I’m part of KUNCI Cultural Studies Center, a collective with shared interest on creative experimentation and speculative inquiry with focus on intersections between theory and practice. We run a library and working space which open for public. Our space is an old house which located in residential area, in the South area of Yogyakarta City. During our first year in the house, few of the neighbors were complaining about us. Because our house is unlike other house. We are not a commercial enterprise or a family. Most of us are young. We work together until midnight. We are not artists or gallery but we work with art.

So to our neighbors, KUNCI is a suspicious place. Despite the growing suspicion, I regularly come to the monthly neighborhood meeting. When they asked about my job, I always repeatedly explain to them that I’m a curator. I invite them to come to KUNCI’s events. One artist group organized monopoly game with few KUNCI neighbors to discuss wealth distribution and property ownership. Some of the neighborhood meetings are hosted in KUNCI events. But for me, the neighbors expectation towards me and KUNCI remains unclear.

Until in recent neighborhood meeting, one of the neighbor challenged me to think further on how to use our office vast back and front yard. She proposed to build a catfish pond in KUNCI backyard and manage it communally. I told her that I don’t know anything about fish and I’m quite useless since all I know is writing. “The catfish might die in my hands,” I said in quite dramatic tone. But then she responded, “If they died, we can eat it together. Don’t worry! We will take care of it together,”.

It’s been one month since we had this discussion. The catfish pond is not yet ready. But I can see my position, including KUNCI, with the community around us, has started to become clear. The relation is not based on professional term, but through series of contacts as fellow neighbors. Through the catfish proposal, I started to realize that collaboration should not only limited to project or as a work. Livable collaboration is a mode of living. This is a call to expand the realm of institutional practice, not only as a place to work or production. Institution can provide a spiritual and ideological kinship which function as a site for radical social reproduction. How an institution can live —not only work— alongside other modes of living and gathering?

At the end of 2016, the title and conceptual framework for 15th Istanbul Biennial was announced by the curators, Elmgreen & Dragset. The title is “a good neighbor” and serve as a framework which: “(…) will deal with multiple notions of home and neighborhoods, exploring how living modes in our private spheres have changed throughout the past decades (…) and neighborhood as a micro-universe exemplifying some of the challenges we face in terms of co-existence today”. This is an excellent example on how issues on livable collaboration, co-existence, the change in living modes are being addressed in a large scale, international art event such as biennial.

Yet, I wonder if a biennial can be a good neighbor. What kind of biennial would it be? A biennial who share the same uncertainty in life as we are, and willing to discuss the strategies on surviving in collaboration. Biennial as a good neighbors, perhaps similar to what Raqs Media Collective had imagined by asking: “can we imagine a biennale stretching to become something that happens across two years rather than something that happens once every two years?”. A biennial who isn’t consuming resources and taking it all into its own body, but redistribute them. A biennial who gives instead of constantly takes.

The above-mentioned questions are not only relevant to biennial. It’s also for art projects, collective, institution and other forms of organizing and producing within art. And I would like to extend the notion of neighbor, not only as people whom we live close by, but also any living being that inhabiting this time and space, the universe, together with us. We are living together in precariety. Then what’s left to learn in our precarious living, from one crisis to another, is how to survive in a livable collaboration, both as a good neighbor and professional, in work and life.

0 notes

Text

On Relation, Trust, and Banana: Conversation with Mai Nguyen Thi Thanh (2016)

D (Syafiatudina) : Hi Mai, can you tell me about your project during your residency in Kunslerhaus Bethanien, Berlin?

M (Mai Nguyen Thi Thanh) : My current (ongoing) project in Berlin focuses on the concept of identity and human relations, including on social media sites. I work with over 10 young women, aged from 25 to 35 years old, each with a clearly different appearance. I take photographs of myself in the private spaces of these young women (usually their bedroom or working place), having dressed myself in their clothes and jewelery, and used their accessories to change my hairstyle and hair color. Through this metamorphosis, I borrow and imitate the identities of these women, in order to “become” a completely new person. The end result of this process is a photo series of the different identities.

D: So before you take photos in their home, you discuss with them about your project?

M: Actually it’s not only taking photo. I call this process is an adventure. Since the first time I saw them, talking with them, go inside their room, their world. It was very hard. When I started to approach a girl in the street, I kept thinking on how I can start to talk with her? Will she like my idea? Will she think that it’s stupid? Will she believe in me? Or think that i am a swindle? The feeling when walk in to the house of a stranger, it is also very interesting. The darkness in the old wood staircases, sound, smell. And when you come inside their room. It feels like another world opened. Each room is the unit. And every stuff inside of these rooms told me many things about their owner. Then I did a performance there. I will behave as if I am the owner of that room, in that moment, with another life, another history. One photographer follow me and document this process. And off course, I had to talk with the girls about my project. From the things I learned from them, I do a performance where I tried to be them.

D: I will move away from your current project for a bit and ask you about your previous projects. I saw some of your previous works and your works were always involving other people. In few works, people, community members, or families were your collaborators. Then for your project in Berlin, relation with people is an important aspect as well. How you would compare your experience working with people in different places and context? Do you find any differences or similarities?

M: I think you have not seen all my works yet. I have just worked with people in the last 2 years. My previous works were focused on bodies and genders. I love to work alone in my studio. Frequent social contact makes me feel uncomfortable.

In 2013 during the residency in South Korea I had the opportunity to meet some Vietnamese illegal workers there. The opportunity enriched my insight into this community and I was very surprised how I learnt from them many things. In 2014 during the residency in Sa Sa Art Project-Phnom Penh, I got the chance to meet the Vietnamese migrants who lived in Cambodia and have no personal/identity papers. They have lived there generations to generations, experienced wars, genocide, starvation, survived and are expecting for good things to happen in the future. Those experiences had evoked my interest for history, people, and matters related to identity and migration. Then I realised that I didn’t know anything about the world around me. Talking and approaching other people taught me many things about life. With the Vietnamese migrants living by the Tonle Sap lake far away in Cambodia, I learnt a lot of history, about the fears and hopeful. Through the living time in Berlin, I learnt to live in a strange cultural environment with the limitation of my English. The local people I work with are from different cultures and in different situation, but still they all have own daily matters to deal with. Sharing is the way to make us stronger.

D: So back to your current project in Belrin, can you tell me a bit about this people? How you meet them?

M: Well the girl that you see now with pink hair. I met her in a flea market near my house. When I first saw her, her outfit looks so impression for me. She looks like a little girl. She wears colorful staff, a lovely bag with kids style and chew candy. She holds her boyfriend’s hand and they look very happy.I think her identity and character are very different to me. So I want to know more about her. I came and talked with her about my project. I asked her to meet again and maybe to take photo in her house. And she said yes, why not? She gave me her e-mail. I visited her flat and talked with her for a long time. We talk and wrote email together. And from that I learned that she had not only one glitter side which I saw. She also suffer from personality disorders, eating disorders, depressions, anxiety, panic attacks since experiences she ever got. So she was not really comfortable with stranger. Her boyfriend was always beside her every time we met. The beautiful and colourful appearance seem to be the way that she used to confront with her problem. When I visit her flat, it looks like a shop. A real shop. She has many staff, colorful things, photos and many unicorns. I got overwhelmed there like I’m coming to another world. I want to look at all her staff, sometimes I was worried that my excitement could be consider as rude gesture. But she showed me her space with a pround and exciting also. It’s a wonderful feeling. I’m really happy with that.

D: Yea, I can see that from the pictures. I’m now comparing her room with your room in Bethanien. I remember that you always wear dark colors for your clothes. So when I see you in this pictures, it feels to me that you are a different person. How does it feel for you when you do the performance by imitating their identity?

M: I don’t feel comfortable. I don’t like performance, dancing, or do anything same in public space. I feel afraid if people looking at me. I don’t feel confidence in my own body. So when I do the performance, I tell everyone to leave.

D: You tell the owner of the house to leave as well?

M: (laughing) Maybe she thinks I’m crazy. She invite me to come to her house, use her clothes and staff. And when I start my performance, I ask her to leave because I was too shy. I feel shy if they stand there and saw me do my performance. And maybe. Maybe if someone try to do performance to look like me, I think I don’t want to see that. It’s like looking at a mirror and I don’t want to see myself. So it’s better for them to go away that room when I do my performance.

D: When you do the performance, you can ask another persons to leave. But in your exhibition, you will put your photo in front of the visitors, in public. What’s your feeling about this? Are you afraid? Do you think, as an artist, you will continue to do performance?

M: Photo is easier for me, cause it’s just show a moment pass. I don’t get the pressure that some one looking at me, judge me. I ever tried to do perform 1 or two time with some friends, and then I decided to give up. It’s too much for me.

D: Now, you already have 4 persons who participate in your project and you will look for more. After four experiences of copying other person’s identity, do you feel any difference in yourself? Is there any change in your self?

M: I’m not sure how my self was impacted, let’s see it later. But this process help me learn more about my self and other people. I’m not good in communicate. I was very afraid when start this project. I’m afraid to meet stranger with different language, afraid to be far away my familiar world, afraid to touch to the private of another one. It was a challenge experience but very interesting.

D: How you come up with this idea?

M: This is my first time in Europe, a place so distant from home geographically and culturally. It is a place where I harbor no past, no judgment, no binding: a place where nobody knows who I am. I am constantly occupied with the idea that I could become anyone here, do any crazy things, and forget about all of the social boundaries and taboos in my homeland. But identities are invisble, strong attached roots. There are morning wakened up, with a muzzy mood in the restroom; listening to the noises downstair in the backyard in a strange language, suddenly I’ve realised that I am in Germany. That feelings repeats many times in my first month, when I saw someone young laying down on the grasses sunbathing, with a bottle of beer holding in hand, or when i walked in a dancing groups of drunk people. Feeling lost/ as an outsider/ as a stranger is obvious and frequently. This project as said above is an adventure of mine in the western, a strange world, in which the questions about cultures, freedom, liberation were raised

D: Can you tell me about the other persons that you’ve met for this project?

M: I’m working together with a punk now. Before my project is focusing on young girl from 25 to 35 years old. I didn’t focus on older people. But this woman made me change. I met her in an afternoon when I walking on street. I just saw her from her back. She look big and strong with a Mohawk and green hair. She was holding hands with one person behind her and walking slowly. It’s look peaceful and lovely. When I overtake them to talking, she introduce her daughter who is 14 years old. You know, I was talking with a punk mother, it’s so interesting. All mother I know, they look serious, gentle, many people think that sacrifice is a quality so they ignor their favourite since their youth, try to look normal like people around. I was very curious about this mother. I learned many things from her ; how she slept with her Mohawk hairs , how she overcame the cancer, how she brought the abandoned animals back home. The living room of her family is small, but they still shared it to the refugees. I feel by her the fulliness of love and liberty.

D: You told me that you also made series of dictionaries which compiled words you’ve learned from your collaborators. What’s your favourite word so far?

M: It can be called “dictionaries” or simply observations of key vocabularies from the conversations with my collaborators. It is kind of a guide map to the constructions of my conversations. For my favourite word so far, I think I will choose Punk. I don’t know what’s punk before. I learned from the punk woman that “To be a punk is more than “a style”, it’s a way of life”. I learned many things from people I’ve met.

D: I like the idea of learning from other people. I think learning is not only from school or teacher. We also learn many things from our mothers, friends, or neighbors. I think your project is also a way of learning from other people’s experience or life. It’s a school of life. Do you have favorite person or experience from your project so far?

M: I think each person is special by their way. So the whole process is very interesting for me. There’s another process on how I meet people. Should I tell you about the process?

D: Yes. Please!

M: Okay. So do you know Tinder? Do you use it?

D: No. I’m afraid that I might meet a criminal or serial killer through Tinder. Maybe I’ll try it when I have more confidence (laughing)

M: As you know, Tinder is a dating application, where people find each other by exchanging photos and some brief informations. I had created many different accounts there. Each one is with a fake name, fake age, fake photos and fake indentities to speak with the men there. With some roles I had many “super like” and flirts, with some I received nothing. There are some who didn’t reply or even broke up the contacts. Appearance is the only thing to get attention there. At first I worried that lies and playing roles like this will take advantadges of the faith and feelings of others: But most of the people I met don’t take the relation on Tinder so serious. There too many choices at a glance. I will use few of the chats for my work. It can be a video installation. Of course all participants will stay anonym.

D: I’m thinking about trust now. I told you that I don’t use Tinder because I don’t believe in stranger. Do you think in this project you have more trust on strangers, on people?

M: I thought when I trust people, they will also trust me. Even I am a liar while using a fake indentity on Tinder, my feelings were true. Probably all of us are liars. All the beautiful, sexy, funny pictures, showing a lot of muscles. What do we want to show by presenting these pictures to other people? Is it the image that we want others to look at? Is it the expectation for attention from others?

D: I think what you said is important. When you trust people, they will believe in you. I can’t imagine if I’m you. I also come from Yogyakarta where almost everyone know each other, especially in the art scene. And I don’t think I can start to interact with stranger when I’m in new city. I imagine you are like jumping to the ocean. You don’t know what will happen. If it will success or fail.

M: Anyway I don’t think that the trust is important here – on Tinder. People don’t looking for trust. They might looking for fun. They also might do like this just for pretend, in order to release and relax from stress of being who they really are. Or maybe they just to find something to fill their lonely.

D: After you told me about your project in Berlin, I start to remember my experience when I did residency in Frankfurt, Germany. At that time, I always feel lonely, but not sad. I’m happy to see new things, places, and having new experiences. But I also feel disconnected. Do you think this project relates to the experience being disconnected in unfamiliar (foreign) place and you want to find connection with the people?

M: Yes. It has improved me to open my mind and my self to connection with the people. In this project, my focus on fake identities raises various questions about identity, culture, and the relationships between humans and social networks. Using this nexus as vantage point, I’m projecting my feelings and analyze the loneliness and the loss caused by migration.

D: You said to me that your project is focusing on the social network. Nowadays, when we talked about social network, we will think of social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter. Yet, there’s also social network through face to face interaction, in real life. And in your project, you mix this two types of connection, digital and real time, through meeting people in the streets and on Tinder. How you would compare this two types of connection?

M: These both connections enable me to get in contact with people whom i rarely meet in my daily life. You must have seen some people in your life on the streets, on train or in the markets who made you curious and wish if only you could know more about them. In a glance of hesitation you both passed by and probably never have the chance to encounter each other again. This project encourage me to touch the life of strangers. I also enjoy to talk with strangers on mobile phone apps. It's like reading a book and free your imagination as far as possible. Our sense won't be limited with either the visual impressions about the appearance, colours, noises or smell. A man on Tinder told me: “If you meet people in real life, they wearing a mask of being friendly and polite. But in the internet, people are very fast on showing their real self. They lose the mask so fast. Because why should you wear a mask, if you never see these people in real.”

D: My last question is on trust. You said people on Tinder, they don’t look for trust. They look for something fun to do. But then, when you talked to someone on the street, it also needs trust. They need to trust you and you need to trust them. So I think your approach is a test of trust. But nowadays, we know that it’s hard to trust other people, strangers on the street, especially with the recent bombing incidents in few places across the world. So what’s your opinion about trust in your project? Do you think we can still have trust to other people?

M: Your question reminded me of my childhood. Sometimes on the days when my mom received her salary, she bought for her 3 kids, each one of us a banana. I usually save for the last. My elder brother was always the one who finished his banana first and came to me asking for one piece of my part. He always promised just to bite a small piece and never kept his words. I was very upset and swore never to trust him again. I will never give him anything again. But then the next time, I still trusted him and gave him mine. I still love to trust people. Even when life is not as simple as losing a piece of the banana. But if I don't have faith in people, I think I will lose more.

0 notes

Text

Numpang as inhabiting threshold (2016)

Essay for Radio KUNCI at ifa Gallery, Berlin, April 2016

What is numpang? A friend of mine has been living in a communal house for his whole life. Once he lived in and took care of the headquarters of an artist-run space in the south of Yogyakarta. He didn’t pay the rent but he took a great deal of care of the house. He was numpang in the artist-run space headquarters, of which he was also a member. Numpang is taking a shelter, living in a place that “belongs” to someone else.

On a daily basis, this friend of mine would clean the house, repair some broken things, or make the house comfortable for other members when they come to visit. The house was a workshop for artists to produce silkscreens or linocuts. It was also the place for them to drink and hangout. After the hangout session ended, they would go home to their own individual places, except for my friend. He stayed in the house, because he lived there. Thanks to my friend’s daily efforts to take care of the house, including cleaning, repairing and rearranging things, it became a convenient space to work together for the collective. So the collective is numpang on my friend’s efforts to take care of the house. Here, numpang becomes a moment of dependency. Something depends on other things in order for certain things to exist.

The city centre of Yogyakarta is a dense area. In a very packed urban kampung (village), the street serves as the extension of houses. In the morning, women gather in the roads in front of their houses, to feed their kids, or do grocery shopping from mobile vegetable sellers. They exchange gossip, interact with each other while taking care of their children or doing other domestic chores. In the afternoon, the men will hang out in a few spots on the street near their homes, to smoke, drink coffee, as well as to gossip. When I passed the road where a group of men and women gathered, I would nod my head while saying “numpang..” Here numpang is a polite gesture that serves as an acknowledgement that I am temporarily using their space and creating a rupture in their time. Although the street belongs to the users, such as myself, I also consider it to be the neighbourhood collective space which I should respect. The collective space is shaped by the porosity of personal and domestic space (home) into public space (roads). These groups of men and women allow me to pass by because they are also numpang in the street. They use it temporarily to gather together.

In another case, a friend lived in someone else’s home for one year although the initial plan was to stay for one month. The owner of the house felt disturbed by this overstaying guest but did not know how to express her resentment. Because in numpang, there’s no written agreement on the rights and responsibilities of each person involved. It is based on trust and generosity. So numpang can easily escalate into parasitic numpang. Yet the uncertainty of numpang can create a space for relationships to grow into something else in the future. But the room to grow comes with consequences, such as insecurity.

This condition of encounters which filled with precarity reminds me of one chapter which entitled Contamination as Collaboration in Anna L. Tsing’s book, The Mushrooms at the End of the World. In this chapter, Tsing wrote about how everyone carries a history of contamination and we are being contaminated by each other through encounters. In Tsing’s own word;