#(his art is so varied but always can tell he's sensitive to beauty in plenty of ways from how its drawn)

Text

the way nix draws people- how detail orientated he gets but in an 'i noticed the way they almost smiled about x thing and it was so different from the way they smiled about y thing' and it being true of him in general

sometimes, takes creative liberties and it's almost silly things like 'i can picture this flower that suits them in an certain spot of them' (way he doesn't want to share it cuz fears somebody might be bothered by it/or unsettled- plus dead obvious adoration of whatever nature breathes into his art despite him)

he especially loves realistic moments, where they're just doing whatever and just exist in space (alternatively sometimes sunshiney people are depicted accordingly with some contrasting thing *usually him* in his art)

#<< falling apart at the seams i cant deny >> headcanons#(it goes in hand with how he sees people very nicely)#(he's very people are complicated and actually pretty atune to their positives more than negatives unless has to be)#(his art is so varied but always can tell he's sensitive to beauty in plenty of ways from how its drawn)#(or how he just wants connection so badly)#(nix could take one look at his most damaged siblings and be like the horrors are not all they are)#(not himself though- with himself its like an constant back forth and it shows in usually if draws himself its formless in an way)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hi!!! :D :D :D

“Yeah, when I got to that scene and Pesto said “you start singing, Bjoharn” I paused the game and freaked out for a moment, all “AGDHFMXKDISKSB I GET TO HEAR MY SON SING?????” I love that scene sooooo much ;;o;;”

- We will sing hugging as if we were toasting in a bar XD

“ALSO Pesto just has the most amazing bass skills…like she learns everything by ear and has a great memory for how it goes and seems to know exactly where to put her fingers, and all she needs to be able to do that is to listen to the actual song once and then just a brief recap of it??? Pesto’s bass-playing just kicks a whole lot of ass >o>”

- She could use it to literally hit someone, but she really likes his bass so clearly she isn´t going to, but she can use a skateboard to hit Death or Fam if they hit her on the skateboard 👍

“It’s a great show in my opinion, it’s very interesting! I think it’s by the same people behind the Cornetto trilogy, if you’ve heard of that :o I’d recommend it to anyone who’s interested in that sorta premise ^_^ (…unless they happen to be sensitive to the “eye scream” trope)”

- I would look at all that, if it weren’t that I have a lot of work :,v

Also live-action series don´t appeal to me much, I like animation better ^^

“I watched that entire series before writing this reply, it was a lot of fun to watch! I think I missed any mention he might’ve made about Red Eye, but it’s pretty cool to know that those three guys in the background are creator cameos o:”

- In one part he says the man behind War had to be changed in the switch version for narrative reasons ;)

In the latest version he has a red eye on the shirt, red eyes ( :v ), and a tattoo on his arm identical to the logo that Milky has on his jacket.

“Fandoms are a tricky thing indeed…it feels like NSFW artwork is kinda unavoidable no matter what fandom you’re in, and while I don’t make NSFW stuff myself I know that people are gonna draw what they’re gonna draw, and as long as it isn’t hurting anybody or portraying anything unethical it’s not really my business to call them out on it. However if people are gonna post stuff like that, they should be very responsible about making sure the wrong demographic doesn’t see it, giving plenty of warnings and tagging stuff appropriately, all that stuff. I don’t know what protocol there usually is for that sorta thing, but everyone should make sure that nobody gets scarred for life by anything and that everybody gets along and doesn’t make anybody else feel unsafe!”

- That was just what they didn´t do :) They put their drawings everywhere and in hashtags that had nothing to do :/

Besides, it was the only thing they drew, so if by chance you entered any of the thousands of hashtags that they put, you were going to find a whole block of NSFW

“You shouldn’t have to feel like you’re intruding in fandoms! If your contributions to the PP community are any indication, you probably bring a lot of cool stuff to any fandom you join! Personally I look forward to you submitting things here and I always love seeing your new drawings ^__^ It’s always fun to be able to talk to you about what we both love in the PP verse and swap headcannons and stuff!”

- I also love talking to you, your contributions to fandom are great! I always see your page in whenever I can and I get very excited when I see a new drawing X3 ♥

“Your new drawings are, as always, absolutely brilliant!! I love the reverse AU one (Skeleton Bjørn = very yes) and also the one with you (if that person is you?) hugging Death |D His expression is great, all “yep, this is my life now””

- Thanks ^^ And yep, that little person is like my avatar. If Death were real I would be hugging him all the time. He wouldn´t know how to explain to his mates who I am and what I do there XD

“…I see you brought Pesto with you…might I join you on your quest? I must avenge my viking son >_>”

- You don’t know how happy this drawing made me :D ♥ I was smiling all night ^^ ♥

We are united to protect Bjorn! ♥

-It´s good in your country there are already vaccines for citizens, in my country they came but only for those who work in health and education

Bjorn with the Pesto clothes! I’m going to die of love!!! X3 ♥ ♥ ♥

Love him a lot! ^^

And about the Pesto’s letter: I understood the reference ;) And it’s very funny XD

——–

I want to hug him tightly and never let go ;;u;;

Ah yeah, there’s that too |D But that makes me wonder, do you think that Pesto’s as into skating as the rest of them? I know the developer said that everyone in Hell is obsessed with skateboarding, but the closest thing I could tell that Pesto was passionate about in the game was playing bass, so I’m not certain o:

I totally get that ;;=o=;; I’m also more into animated stuff, there isn’t a lot of live-action stuff that I get attached to but the Cornetto movies are kinda different ^_^ I understand if you’re not into them though, they might be too gory for some people and I know everybody’s preferences vary!

Just replayed the Switch version and I think I found him! Don’t think he had an eye on his shirt though O.o

Assuming you’re talking about DeviantArt, do they not even put a mature content warning on their works? I’ve been away from dA but I know you have to do that if your art is NSFW o_O If they don’t, then that’s super uncool of them >A> And if you’re talking about another site, I…am probably not so knowledgeable :P

I’m so glad to hear that!! It makes me happy to know that you look forward to my art ;;u;; I also get excited seeing new drawings from you, whether it’s here or on the discord ^___^

Bjørn and Milky would have very similar problems with me :P I’d just be hugging Bjørn all day and be all like “don’t hurt my son or I will curse you” to anyone who passes |D

Well seeing your submission made me smile all night, so I guess we’re even ^_^ And yes, the whole world must unite to protect the best boy!!

I only got mine early due to a condition :P

If I’m going to die of anything, it might as well be out of love for my beautiful viking son ♡♡♡ And I figured you would notice that >u>

1 note

·

View note

Text

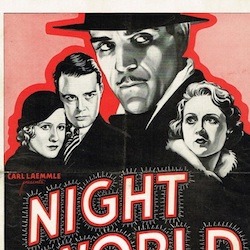

ALL THE WORLD’S A NIGHT CLUB

Clocking in at 58 minutes, Night World (1932) may still hold the record for how much can be packed into an hour of celluloid. This compact tale of one night in the life of a Manhattan hot spot bursts like a Christmas cracker, spewing forth dizzy glamour, drunk humor, risqué antics, weighty melodrama, leg art, poignant tragedy, tap-dancing chorus girls, trigger-happy gangsters, adultery, tender budding love, and wisecracks zinging through the air in a free-for-all. The pace is so accelerated, the shifts in tone so whiplashing, that it plays like one of those condensed-Shakespeare gags; yet, far from jarring, it all blends like a well-shaken cocktail. You’re not sure what you’re drinking, but it goes down easy.

An opening montage offers an apertif of bright lights, dark streets, flowing booze and floozies on the prowl; and a heavy dose of warning in a murder victim felled by a shot, a dirge-like Salvation Army parade, and a little boy saying his prayers—just to remind us that there is such a thing as innocence. Then we arrive at the entrance of Happy’s Club, a whirlpool of frivolous debauchery run by the affable yet sinister Boris Karloff, who calls everyone “big shot” and spends most of his time seething over his faithless, bitchy wife.

The irony of the club’s name is spelled out by Tim (Clarence Muse), the sage black doorman, who says that the nightly revelers are hungry, but not for food, “maybe they don’t know what for.” Inside, in the bright blur of liquor and women and jazz, they think they’re happy, but when they come out, it’s the same cold, sad world. “That’s real starving.” Despite the demeaning dialect (he says things like “I’se a philosophizer”), Tim is an example of the much greater depth and dignity allowed to racial and ethnic minorities in pre-Code Hollywood. They might be the butt of jokes, but they’re also real people; one thread running through the film is Tim’s anxiety over his wife, who is in the hospital. His continually frustrated efforts to find out how she is, and to get away to be with her, come as reminders of that cold, sad world beyond the nightclub.

It’s not a speakeasy (Happy “just serves white rock and ginger ale and hopes nobody dies on the premises”) but the guests bring plenty of their own ammunition. A fat drunk spends the whole movie looking for someone from Schenectady; a giggling, helium-voiced blonde drives her escort to despair; a flamboyant pansy responds to a chorus-girl’s come-on with a sniffy, “That’s Mister Baby to you.” The wised-up girls are always dishing out smart cracks, telling each other how they told him where to get off. George Raft at his most reptilian boasts about winning 11 G’s off “some ump-chays from Philadelphia.” A bootlegger stops in to warn Happy of the consequences of buying his stuff from the wrong supplier. Mrs. Happy slinks around dripping venom, ducking into closets to smooch the dance director.

At the center of the film is the morosely plastered Michael Rand (Lew Ayres), a poor little rich kid who sits alone, punishing himself with bad liquor because his mother shot his father in another woman’s apartment. He’s redeemed by a good angel, chorus girl Ruth Taylor (Mae Clarke), who takes him under her wing after Happy knocks him cold, a cure for his alcoholic jitters. She puts him to bed under a bear-skin rug, pockets his wallet so he won’t get rolled, reintroduces him to the concept of water (“Here, insult your stomach with this.”) Clarke, for once in a movie where no one drags her by the hair or slaps her with a citrus fruit, is lovely: both her beauty and her acting style have a natural, unaffected warmth that’s rare in an era of platinum hair and penciled-on eyebrows. Her goodness—not innocence—makes the dazzle of naughtiness look like cheap tinsel. She’s the glass of water you thirst for after a lot of lousy booze. She can hoof too—Clarke was dancing in nightclubs at age thirteen—and her figure in rehearsal shorts would wake any man out of a three-day drunk.

“You know, they can make it faster than you can drink it,” Ruth tells the sozzled Rand, who replies, “Yeah, but I bet I’ve got them working nights.” (A line recycled by Dan Duryea in The Great Flammarion.) Adorable, boyish and clean-cut, Lew Ayres makes a surprisingly effective, and affecting, drunk—looking forward to perhaps his best performance, as Hepburn’s wastrel brother in Holiday. Perhaps because he doesn’t overdo it: there’s a delicacy and restraint even as he is credibly woozy and sloshed. As Ned Seton, he’s the most appealing character in Holiday, with his bitter intelligence, sensitivity and mordant humor; but he’s also a man without a spine or a hope. When he tells Hepburn, as his unhappy sister, what it’s like to get drunk, she’s enticed by his account of the glow and hyper-clarity, the exciting game of navigating a world where every action is transformed into a challenge—but she’s disappointed and disgusted by his matter-of-fact admission of the final stage, when you pass out. It’s a weakness, a sloppy self-annihilation that she could never accept.

When you make your film debut kissing Garbo, it would seem there’s nowhere to go but down, and Ayres’s pretty face might have doomed him to cloying juvenile roles, but instead he had a few years of varied and surprisingly dark films, starting with the harrowing All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), which instilled the pacifism for which he would later be reviled. He played a ruthless Walter Winchell-like columnist battling racketeers in Okay, America (1932); a cad who knocks up the family maid in Common Clay (1930); even an unlikely gang boss in Doorway to Hell (1930). In Night World, Ayres has two scenes that stand out as unassimilated lumps of Drama: first his encounter with his late father’s mistress, who offers a persuasive defense of adultery, and then his meeting with his mother (a mink-swathed Hedda Hopper). This latter scene is over-written and out of step with the rest of the movie, but also shocking: you don’t expect in such an otherwise lightweight film to see a young man bitterly disown his neglectful mother, and the mother admit she never loved or wanted her son. Hopper’s hard, self-satisfied face is chilling; so much for Mom and apple pie.

The developing romance between Ruth and Michael, by contrast, doesn’t feel rushed or contrived. So much has happened so fast in the film that by the time he asks her to marry him and sail for Bali the next day, it doesn’t seem like an unrealistically hasty move. In its last five minutes Night World kicks into an even higher gear: after one stabbing moment as Tim learns that his wife has died, gangsters burst in with guns blazing, and the new couple’s first kiss looks likely to be their last as they cower before a twitchy, psychotic Jack La Rue. When their lives are saved by the timely entrance of an Irish cop, they and the movie walk over the bodies of the dead for a last few giddy jokes as they set out for their new lives—in a paddywagon.

Just another night on East 53rd Street.

by Imogen Sara Smith

#Imogen Sara Smith#The Chiseler#Night World#Mae Clarke#The Great Flammarion#Doorway to Hell#Pre-Code#Hedda Hopper

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Fen’Sulahn AU sibling bonding for @justanartsysideblog!

Mythal wants them each to have their own territories.

Their own followers.

Dirthamen is not surprised when Falon’Din detests the idea. They are not meant to be separated like that, he insists. They should rule together, should decide things with one another. He does not say as much, but he dislikes the idea that they will live in regions separate of one another. Rule them and be obliged to stay in them, and to spend their days with people who are not Falon’Din.

Of course, they already do this, to varying extents. War has been persistent in their empire, and the territories that they have claimed have not come easily. There are few generals whom Mythal trusts as well as her own children, and many of those equally or even better accomplished at the art of war have fallen to their enemies.

Or… to Mythal, it would seem.

Dirthamen attends the funeral of General Suladahl, along with his siblings. The former Keeper had been among the first to ally their clan with Mythal and Elgar’nan, and to denounce the systems of the clans itself. She had taken up a post as tactician and warleader, had been, so far as he could tell, irrefutably dedicated to their cause, and believed fully that uniting the People and guiding them into a new era of prosperity was not only valorous, but necessary.

She had been his mother’s friend.

Mythal had, so far as the rest of the empire knows, killed the assassins which crept into her dear friend’s bedchambers. She is red-eyed as she oversees the proceedings herself. Her grief seems genuine. Her words of esteem, heartfelt.

But his mother had come to him, afterwards. Her secret keeper. There are some secrets she does not even share with him, but this one, she had. In soft, low words, she had told him. I killed Suladahl. The assassins’ bodies were those of slaves that I took from the camps. She… she was expressing concern, over some of our plans. Foolish concerns, but she would not be dissuaded from them. She threatened your brother and sister.

Dirthamen cannot imagine General Suladahl threatening his siblings.

But, he has never been good with people. And she had possessed many secrets – nearly as many as his mother, and unlike her, she had not been inclined to share them with him.

Next to him, his sister is as red-eyed as their mother. She had liked Suladahl. They had served together on many battlefields, had saved one another’s lives on more than one occasion. Dirthamen does not know if they had been lovers, but they had certainly been friends. Falon’Din had never liked it. He never liked anyone of rank or sway becoming too close to them. He always thought that such people were attempting to come between the three of them.

Perhaps he is not wrong. Perhaps Suladahl had been. It would further explain his mother’s actions. But…

He does not feel well, all throughout the funeral.

Olwyn keeps her composure well enough through the ceremony, but when she is brought forward to plant the seeds that will mark her friend’s grave, her hands tremble, and her misery and grief become too abundant to disguise. Mother whispers to her, her face gentle, and excuses them all from the rituals that follow. They are not needed for them. Falon’Din puts his cloak over Olwyn, to help disguise her upset, and sighs at her.

“You are too sensitive,” he says.

Olwyn gives him a sharp look.

“I do not think you would be so blithe if one of your friends was being buried today,” she counters.

Falon’Din makes a face.

“If it were one of mine, I would not be weeping about it,” he insists. “Grief does not resurrect the dead. We should go and teach our enemies a lesson. Remind them, that for every one of us they take, we will cut down a hundred of them. If not more.”

“The assassins are already dead. Mother killed them,” Olwyn points out. “There is nothing left to do but grieve. So I will.”

Falon’Din sighs again, but he does not argue with her any further. Dirthamen is glad. It is unbecoming to criticize their sister’s feelings – grief must be expressed, so that it does not fester. Tears are not a problem. Unwise actions may be, however. In this, he is on Olwyn’s side, and he would not like for the three of them to fight, now. Falon’Din has been tense enough with the prospect of the division of territories, and arguments between the three of them are exhausting.

They withdraw to Dirthamen’s chambers. Olwyn is only just back from a campaign, and her own are cold and have not been redecorated in the months since she left. And Falon’Din has become increasingly insistent that he does not want his siblings entering his rooms, of late. So they go to Dirthamen’s, which are serviceable, and Olwyn settles onto his couch, and Falon’Din scoffs and huffs but also goes and retrieves some warm tea to help calm her nerves.

Dirthamen sits down beside her.

She lets out a breath, and then leans against his shoulder.

“How did assassins even make it so far into the city?” she wonders. “We have countless wards against such things. I helped make the protections on that room myself. I must have overlooked something…”

Her breaths tremble.

Dirthamen’s secret knowledge scrapes at him. If he tells her, then she will know it was not her fault. But if he tells her, then she will know her friend died by their mother’s hand. He could explain – he could offer Mother’s explanation – but sometimes, even when Dirthamen tries to explain things, his sister still gets angry. Still becomes hurt.

He is clumsy at such things. And their mother bade him to not tell anyone, and especially not tell Olwyn.

You will be tempted to, I know, because you will want her to know the truth. But it would hurt her far worse to think that her friend was conspiring against her, than to simply think that tragedy befell her. Let her mourn someone she loved without the knife of betrayal stinging in her back, as well.

Dirthamen does not want to hurt his sister.

And in the end, it is easier not to speak, than to try and find the words to explain.

“It was not your fault,” he says, instead. Because that is true, and she should know it, at least.

“But if it could happen again… what if they had been even quicker? What if they had killed Mother, too?”

Suladahl and Mythal were of similar prowess on the battlefield. Dirthamen supposes the concept seems reasonable, without all of the available information. The protections on the room were not at fault, however. Olwyn has come to an erroneous – if reasonable – conclusion, but Dirthamen does not know how to correct it.

Falon’Din hands her tea to her, and then folds his arms.

“The room was fine,” he says.

“Impossible,” Olwyn counters. “If it was fine, how did assassins get in?”

Their brother shrugs.

“Traitors,” he asserts. “We have plenty. Mother is too soft-hearted, and forgives too many transgressions. Someone from our side plotted this.”

“Who would ever?” Olwyn argues. “Our soldiers are loyal.”

“My soldiers are not even all loyal, and I have chosen them especially to be loyal,” Falon’Din counters. “But if you want to be stubborn about it, then let us go and check the room ourselves. No one has touched it since the assassins were carted off. That should tell you enough – Mother has probably figured out the same thing that I have. Otherwise, would she not investigate herself?”

Olwyn hesitates.

Dirthamen hesitates, too. Their mother bid him keep her secrets, but she did not say anything about preventing his siblings from seeking out the matter of their own accord.

“Mother was grief stricken, she may not have thought to…” Olwyn ventures, but she does not seem entirely convinced, now. Her brow furrows. She taps one finger against the side of her tea. But after a moment, rather than taking a drink, she sets it down on the small table next to Dirthamen’s couch.

“Alright,” she decides. “Let us go and have a look.”

The three of them venture back out of Dirthamen’s rooms again, and begin to make their way down the corridors of the palace, to where Suladahl’s chambers are. This palace was built along with many of the major structures of the city. Though lately, their parents have been talking of tearing it down, to put something better in its place. A grand conference hall has been suggested. If things go as their mother wishes, she intends for each of them to have their own manors within the city. For housing themselves and their most trusted followers, and of course, one another, when desired.

Dirthamen does not know what he would do with a manor in the city. He supposes his lieutenants can decide most of the matter of what it will be like, and be content with that. He cannot imagine coming to Arlathan for reasons other than to visit with his family; and if he is visiting, then he would he not stay with them?

Falon’Din likes the idea of a palace of his own. Olwyn has not said much about it, except to venture that she does not think rebuilding an already-functional city should be a priority. They have territories to see to as well, after all, and while Arlathan is the jewel of their empire, it cannot possibly house everyone within it. Uncommonly, she had seemed to sway their mother’s opinion on the matter.

At least, for now.

The corridors they trek through are quiet. Suladahl’s rooms were not the only ones in their wing, but the other three influential elves being housed there had requested to be temporarily relocated, in light of the situation. Dirthamen knows that they have been, and where they have gone, and that the area should be empty. The doors into the various quarters are arranged in a circle, with a small, decorative fountain and several benches arrayed around the round courtyard that lets in to them.

Standing next to the fountain is a notably beautiful elf. Dark of hair and elegant of features, dressed in a plain, white gown, with an obsidian necklace hanging in droplets from their throat. Their lips and eyelids are painted white. Discreet, but still in keeping with the trends of the city.

“Melarue,” Olwyn notes, in surprise. “What are you doing here?”

Melarue looks somewhat surprised by their own presence, though Dirthamen is not certain it is sincere. It would be hard to say. The elf is graceful enough in their comportment that he has never seen them express themselves inappropriately. Nor, perhaps, without calculation. After a moment, they incline their head.

“I live here,” they assert, gesturing to one of the doorways. “I had thought to come back and collect some of my things. I do not know how long the investigation into poor Suladahl’s death will take.”

Falon’Din frowns, but Olwyn’s expression twists in sorrow.

“Suladahl always spoke highly of you,” she says.

Melarue inclines their head again, in gracious acknowledgement of the sentiment. Their hair falls freely, like a curtain across their face.

“She saw the best in people,” they say. “Would that the world had accommodated her idealism. She might be with us still.”

Olwyn swallows, heavily. She seems to run out of words, then, and so it is that Falon’Din takes command of the conversation.

“We are here on official business,” he states. “Investigating the area. Most everyone is still at the funeral. One can only imagine why you chose not to remain throughout the ceremony.”

Melarue bows outright, at that.

“I have never been one for funerals,” they reply. “Some find them cathartic. I prefer to mourn in solitude, myself.”

“And of course, you must mourn poor Suladahl so,” Falon’Din scoffs. “Delicate of you not to mention the fact that the two of you were always arguing. I doubt you have shed any tears; but I do not blame you. The woman was insufferable.”

Olwyn makes a sound of protests, and their brother leaves it there.

Melarue’s gaze snaps to his for a moment. Sharper than Dirthamen can recollect seeing it before, but then, they were Cunning, once. And they are obviously more than they seem, even if, like many others, they have never entrusted him with their secrets.

“We may have argued, but I always respected her,” they say.

“Ah. A worthy opponent,” Falon’Din surmises. “But an opponent, even so.”

“Forgive me,” Melarue says. “But if you have business, I would leave you to it. I have matters to see to as well, and I would prefer not to discuss this any longer. Trading barbs is unbecoming, on a day meant to mourn the loss of someone with rare integrity.”

“Of course, I am so sorry…” Olwyn ventures. Melarue only nods, and bows again, and then makes their way through the door they had indicated earlier.

The three of them watch as it clicks shut.

“Suspicious,” Falon’Din decides.

Olwyn rounds on him.

“That was uncalled for!” she snaps. “I know you did not like Suladahl, but I would have thought you better than to speak ill of the dead. You, who has been charged with overseeing so many of their rites!”

Falon’Din folds his arms, and straightens. Annoyed at her scolding.

“I was attempting to get them to implicate themselves more,” he snaps back. “We are looking for a traitor. Melarue lived near to Suladahl, and quarrelled with her, and you know Mother has never trusted them completely. That is why she does not let them leave the city. Melarue could have arranged for Suladahl’s death. Or even for Mother’s. Would you have me ignore the obvious? They probably came back to make certain that the assassins did not leave anything incriminating behind.”

Olwyn’s expression wavers, for just a moment. She glances at the door which Melarue left by. And is still standing behind, according to the whispers from the Dreaming. They are not loud whispers, but Dirthamen is more capable than most of hearing them, and dreams have a way of rustling around elves of a certain quality.

Like Melarue.

Who did not kill Suladahl. Which he well knows.

“That is a harsh allegation,” Olwyn warns their brother.

“Murder does not inspire soft ones,” Falon’Din counters.

“Melarue did not kill Suladahl. Nor arrange her death,” Dirthamen says.

The other two turn to look at him.

“How do you know?” Falon’Din asks, first. Olwyn is relieved enough that, for a moment, he can feel it through their bond and proximity.

Dirthamen cannot give the true answer.

“Mother does not trust them completely,” he says, instead. “They would not be able to manipulate the eluvians, nor the wards upon the palace, without raising alarms. They are innocent.”

Falon’Din snorts at that.

“Not hardly,” he asserts.

“Dirthamen is right,” Olwyn says, rounding on him and folding her own arms in turn. The two look very stubborn, when they do this. Dirthamen wishes that they would not engage in so many confrontations, but, they always have. “If your idea is correct, then it would take someone within Mother or Father’s own circles betraying us for this to come about.”

Falon’Din makes a face, but lets the issue of Melarue go.

“I hope it was General Elase,” he says, instead. “They are always making so much fuss about the work camps.”

“That is a terrible thing to wish for,” Olwyn snaps. “And they make good points, you just do not listen to them well enough. Just because Father-”

“Oh do not start on that again-”

“It is not Elase’s fault that he embarrassed you!”

“He did not embarrass me, he tried to embarrass me, and what’s more-“

Dirthamen settles onto one of the benches, and watches his siblings quarrel. It takes a little more than half an hour for them to get through this particular argument. He focuses on attempting to track the minute progression of shadows cast through the windows, and compare it to the echoes of the space in the Dreaming. He cannot see any trace of what happened to Suladahl, however. The spirits of the area have all been broken. Their fragments removed, and the chamber left quiet.

Mother did that, too, probably.

Eventually, the argument stops, and Falon’Din opens the door to Suladahl’s rooms. Olwyn comes over and takes Dirthamen by the hand, and pulls him into the chamber with her, but stops at the threshold.

Her gaze roves around the room.

“…Oh,” she says.

“What is it?” Dirthamen wonders.

“I did not realize,” she admits. “It is… it is her room. I had lunch with her here, several months ago now. It was the last time we spoke. Right there, at that little table. We had cold summer squash soup, and she told me she was thinking of learning a new instrument. She already played at least a dozen…”

Grief wells up. Though the Dreaming has been wiped clean, it would seem that the space itself still carries too many impressions. Memories. This is an older part of the palace. The courtyard outside had once housed a shrine, he recalls, before the expansion of the city had overtaken it, and converted the temple grounds in the palace ones.

He puts an arm around Olwyn.

“We can leave,” he suggests.

She shakes her head, however. Still looking towards the table. Falon’Din has already left, though. Moving to check the wards instead.

“No,” Olwyn says. “I need to know what happened to her.”

“It was not your fault,” Dirthamen says again, and attempts to instil as much certainty as he can into the words.

Olwyn pauses.

Falon’Din does as well. One of his hands is against the wall. The wards glow beneath it, showing themselves; but before he can finish his assessment, he lets go again, and turns to look at him. Olwyn’s eyes dart across his face, and Dirthamen resists the urge to shift uncomfortably from foot to foot.

“You know what happened,” she says.

He swallows.

“It is a secret,” he says.

Olwyn pushes away from him, as her expression twists with misery. Falon’Din only raises an eyebrow.

“Tell us,” he demands.

“I cannot,” Dirthamen replies.

Falon’Din gestures sharply towards him, as if he has in fact give him all the information he needs.

“There! You see? There is only one person who could compel him to keep a secret from us, and that is Mother. It was an insider. She is probably routing them out even as we speak, and did not want any of us tipping them off. And he knows who it is, which is how he knows it was not Melarue, too.”

Dirthamen loses the battle with himself, and shifts uncomfortably, then. He has given too much away, but Falon’Din’s presumptions have saved most of their mother’s secret, for now. The most important part, at least.

Olwyn looks at him intently.

“You know who it is?” she guesses.

He cannot deny it, but to admit it might be too close to giving up the secret. His sister is good at reading him, however, and draws her own conclusion from his silence.

“You do,” she says, moving closer. One of her hands grips his arm. “Tell me who it was!”

“I cannot,” he replies.

Falon’Din rolls his eyes.

“Please,” Olwyn presses.

“It is no use,” their brother reminds her.

“That is easy for you to say! It is not your friend who is dead!” she snaps back at him, turning to face him. There are tears in her eyes. “If it was Athimel, you would probably already be trying to hit Dirthamen, to get him to tell you!”

Falon’Din grimaces.

“So what? You want to hit him?” he says. “Go on and hit him, then. Perhaps you will have more luck than I do at getting him to betray Mother. The novelty might make your fists sting more, hm? But then do not dare tell me off the next time I do it.”

Olwyn lets go of him so quickly that it is as if his sleeve has burned her.

“No!” she exclaims. The denial rushing out of her, hot and hurried and wet with her tears. A few slip down her cheeks. Dirthamen regrets them. He wishes he could have seen how to handle things, so that she would not be crying in anger and frustration as well as grief, now.

“…No,” Olwyn repeats, swallowing. Her shoulders slump.

Defeated.

“If… if Mother wants it kept secret, for now… then, there must be a reason for it.”

“There is,” Dirthamen confirms.

Falon’Din nods.

“Well. At least now you know it was not your fault,” he concludes. “That was the important part. And you will surely find out who was to blame, when Mother has them brought to the executioner’s block. I will cut their head of myself, if you like.”

Olwyn drops her face into her hands. Tentatively, Dirthamen reaches out to touch her shoulder.

“I am sorry,” he says.

It does not do much good.

~

A month later, General Elase is executed for conspiring against the empire and orchestrating the assassination of General Suladahl.

Falon’Din does, indeed, cut their head off himself. He must argue with their Father for the right to the task, but he obtains it. Olwyn watches grimly as the execution is carried out, and afterwards, their mother takes her away to offer better comfort than Dirthamen’s clumsy offerings would provide.

He cannot help but notice, now, that the only Generals of note who remain are himself, his siblings, and June.

But… if there is a secret behind that, it is not one his mother deigns to share.

15 notes

·

View notes