#2009 iranian presidential election protests

Text

The auditory version of the blank sheet is, of course, silence. Protesting wordlessly was a technique employed by Black Americans in July 1917, when an estimated 10,000 citizens, organized by religious groups and the NAACP, marched down Fifth Avenue in Manhattan to protest racial violence and discrimination. As the New York Times reported, “Those in the parade represented every negro organization and church in the city. They marched, however, not as organizations, but as a people of one race, united by ties of blood and color, and working for a common cause.”

In September 1968, tens of thousands of students staged a silent march calling for greater democracy in Mexico. Contradicting the Mexican government’s accusations that they were resorting to violence, the students protested by simply carrying flags. (Around this same time, civil rights activists in the United States wielded flags with similar goals in mind.) “You’re taking the symbols of the regime and exposing the illegitimacy of the regime at the same time,” says David Meyer, a sociologist at the University of California, Irvine.

Other protests have employed more obvious symbols of repression, including handcuffs, blindfolds and gags. The last of these became widespread as a political prop following the trial of the Chicago Seven (originally eight), antiwar protesters who were charged with inciting a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. During the 1969 trial, the judge ordered defendant Bobby Seale to be gagged and chained to his chair.

Decades before football player Colin Kaepernick created a stir by kneeling during the national anthem, Black athletes silently used their status to fight oppression. At the awards ceremony for the 200-meter dash at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos each raised a clenched gloved fist in a call for global human rights.

The operating theory behind silent protests is that when the cause is clear and righteous, there’s no reason to yell about it—a principle demonstrated by more recent examples of silent protests, too. In 2009, a peaceful rally in Iran against unfair elections ended in gunfire and explosions. To vent their fury, hundreds of thousands of Iranians met at Tehran’s symbolic central roadway, Islamic Revolution Street, and marched quietly to Freedom Square, hoping to avoid a police crackdown. In 2011, protesters in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, stood quietly in solidarity with activists detained without trial by the country’s regime. Multiple times in Hong Kong, lawyers have marched in silence to protest Beijing’s incursions into the city’s constitution and legal affairs.

— The History Behind China's White Paper Protests

#suzanne sataline#the history beyond china's white paper protests#history#totalitarianism#oppression#politics#protests#silent protests#silent parade#mexican movement of 1968#chicago seven#1968 olympics black power salute#2009 iranian presidential election protests#2011-2012 saudi arabia protests#2019-2020 hong kong protests#usa#african americans#mexico#iran#saudi arabia#hong kong

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worry grows for Iran athlete who competed without her hijab | AP News

An Iranian competitive climber left South Korea on Tuesday after competing at an event in which she climbed without her nation’s mandatory headscarf covering, authorities said. Farsi-language media outside of Iran warned she may have been forced to leave early by Iranian officials and could face arrest back home, which Tehran quickly denied.

The decision by Elnaz Rekabi, a multiple medalist in competitions, to forgo the headscarf, or hijab, came as protests sparked by the Sept. 16 death in custody of a 22-year-old woman have entered a fifth week. Mahsa Amini was detained by the country’s morality police over her clothing.

The demonstrations, drawing school-age children, oil workers and others to the street in over 100 cities, represent the most-serious challenge to Iran’s theocracy since the mass protests surrounding its disputed 2009 presidential election.

A later Instagram post on an account attributed to Rekabi described her not wearing a hijab as “unintentional,” though it wasn’t immediately clear whether she wrote the post or what condition she was in at the time. The Iranian government routinely pressures activists at home and abroad, often airing what rights group describe as coerced confessions on state television.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iran Tortures Political Dissidents

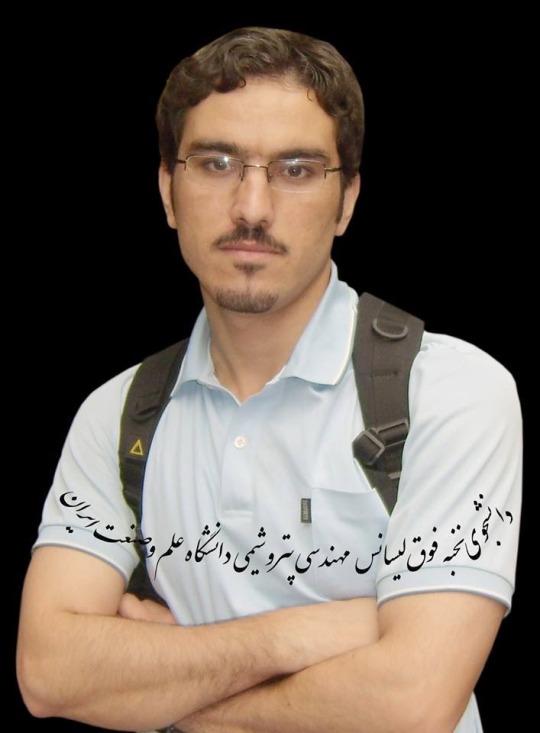

This is Majid Tavakoli. He was one of the heroes of the 2009 protests in Iran. Yes - Iranians have been protesting the Islamic Republic since its inception. The world just didn’t want to know about it.

Majid Tavakoli is an Iranian student leader, human rights activist and political prisoner. He was a student activist and an organizer at Tehran's Amirkabir University of Technology. As some of you may know, the Presidential Election of 2009 in Iran was hotly contested because the Islamic Republic stole the election. Majid Tavakoli was arrested at least 3 times during the protests. The Islamic Republic claimed that he crossed-dressed as a disguise to avoid arrest and in response to such an allegation, a campaign protesting his imprisonment featured men posting photos of themselves wearing hijab.

Majid Tavakoli is once against in Evin prison. He was arrested again during the current protests for woman, life and freedom. Accordingly to reports, Tavakoli has been beaten severely. He was initially in solitary confinement along with other prisoners; however, they are now transferred to another place in Evin prison but no one knows where they are located.

#mahsa amini#jina amini#iran protests#helpiran#freedom for iran#majid tavakoli#protect the prisoners#evin prison#woman life freedom#women's rights#human rights

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The death of Mahsa Amini on 16 September 2022, while in police custody for wearing an “improper” hijab, has triggered what has become the most severe and sustained political upheaval ever faced by the Islamist regime in Iran. Waves of protests, led mostly by women, broke out immediately, sending some two-million people into the streets of 160 cities and small towns, inspiring extraordinary international support.1 The Twitter hashtag #MahsaAmini broke the world record of 284 million tweets, and the UN Human Rights Commission voted on November 24 to investigate the regime’s deadly repression, which has claimed five-hundred lives and put thousands of people under arrest and eleven hundred on trial. The regime’s suppression and the opponents’ exhaustion are likely to slow down the protests, but unlikely to end the uprising. For political life in Iran has embarked on an uncharted and irreversible course.

How do we make sense of this extraordinary political happening? This is neither a “feminist revolution” per se, nor simply the revolt of Generation Z, nor merely a protest against the mandatory hijab. This is a movement to reclaim life, a struggle to liberate free and dignified existence from an internal colonization. As the primary objects of this colonization, women have become the major protagonists of the liberation movement.

About the Author

Asef Bayat is professor of sociology, and Catherine and Bruce Bastian Professor of Global and Transnational Studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His latest books include Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring (2021).

View all work by Asef Bayat

Since its establishment in 1979 Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s, the Islamic Republic has been a battlefield between hardline Islamists who wished to enforce theocracy in the form of clerical rule (velayat-e faqih), and those who believed in popular will and emphasized the republican tenets of the constitution. This ideological battle has produced decades of political and cultural strife within state institutions, during elections, and in the streets in daily life. The hardline Islamists in the nonelected institutions of the velayat-e faqih have been determined to enforce their “divine values” in political, social, and cultural domains. Only popular resistance from below and the reformists’ electoral victories could curb the hardliners’ drive for total subjugation of the state, society, and culture.

For two decades after the 1990s, elections gave most Iranians hope that a reformist path could gradually democratize the system. The 1997 election of the moderate Mohammad Khatami as president, following a notable social and cultural openness, was seen as a hopeful sign. But the hardliners saw the reform project as an existential threat to clerical rule, and they fought back fiercely. They sabotaged Khatami’s government, suppressed the student movement, shut down the critical press, and detained activists. After 2005, they went on banning reformist parties, meddling in the polls, and barring rival candidates from participating in the elections. The Green Movement—protesting the fraud against the reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi in the 2009 presidential election—was the popular response to such a counterreform onslaught.

The Green revolt and the subsequent nationwide uprisings in 2017 and 2019 against socioeconomic ills and authoritarian rule profoundly challenged the Islamist regime but failed to alter it. The uprisings caused not a revolution but the fear of revolution—a fear that was compounded by the revolutionary uprisings against the allied regimes in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, which Iran helped to quell.2 Against such critical challenges, one would expect the Islamist regime to reinvent itself through a series of reforms to restore hegemony. But instead, the hardliners tightened their grip on political power in a bid to ensure their unrestrained hold over power after the supreme leader expires. Thus, once they took over the presidency in 2021 and the parliament in 2022 through rigged elections—specifically, through the arbitrary vetoing of credible rival candidates—the hardliners moved to subjugate a defiant people once again. Extending the “morality police” into the streets and institutions to enforce the “proper hijab” has been only one measure—but it was the one that unleashed a nationwide uprising in which women came to occupy a central place.

Women did not rise up suddenly to spearhead a revolt after Mahsa Amini’s death. Rather, it was the culmination of years of steady struggles against a systemic misogyny that the postrevolution regime established. When that regime abolished the relatively liberal Family Protection Laws of 1967, women overnight lost their right to initiate divorce, to assume child custody, to become judges, and to travel abroad without the permission of a male guardian. Polygamy came back, sex segregation was imposed, and all women were forced to wear the hijab in public. Social control and discriminatory quotas in education and employment compelled many women to stay at home, take early retirement, or work in informal or family businesses.

A segment of Muslim women did support the Islamic state, but others fought back. They took to the streets to protest the mandatory hijab, organized collective campaigns, and lobbied “liberal clerics” to secure a women-centered reinterpretation of religious texts. But when the regime extended its repression, women resorted to the “art of presence”—by which I mean the ability to assert collective will in spite of all odds, by circumventing constraints, utilizing what exists, and discovering new spaces within which to make themselves heard, seen, felt, and realized. Simply, women refused to exit public life, not through collective protests but through such ordinary things as pursuing higher education, working outside the home, engaging in the arts, music, and filmmaking, or practicing sports. The hardship of sweating under a long dress and veil did not deter many women from jogging, cycling, or playing basketball. And in the courts, they battled against discriminatory judgments on matters of divorce, child custody, inheritance, work, and access to public spaces. “Why do we have to get permission from Edareh-e Amaken [morality police] to get a hotel room, whereas men do not need such authorization?” a woman wrote in rage to the women’s magazine Zanan in 1988.3 Then, scores of unmarried women began to leave their family homes to live on their own. By 2010, one in three women between the ages of 20 and 35 had their own household. Many of them undertook what came to be known as “white marriage” (ezdevaj-e sefid), that is, moving in with their partners without formally marrying. These seemingly mundane desires and demands, however, were deemed to redefine the status of women under the Islamic Republic. Each step forward would establish a trench for a further advance against the patriarchy. The effect could snowball.

While many women, including my mother, wore the hijab voluntarily, for others it represented a coercive moralizing that had to be subverted. Those women began to push back their headscarves, allowing some of their hair to show in public. Over the years, headscarves gradually inched back further and further until finally they fell to the shoulders. Officials felt, time and again, paralyzed by this steady spread of bad-hijabi among millions of women who had to endure daily humiliation and punishment. With the initial jail penalty between ten days and two months, showing inches of hair had ignited decades of daily street battles between defiant women and multiple morality enforcers such as Sarallah(wrath of Allah), Amre beh Ma’ruf va Nahye az Monker(command good and forbid wrong), and Edareh Amaken(management of public places). According to a police report during the crackdown on bad-hijabis in 2013, some 3.6 million women were stopped and humiliated in the streets and issued formal citations. Of these, 180,000 were detained. But despite such treatment, women did not relent and eventually demanded an end to the mandatory hijab. Thus, over the years and through daily struggles, women established new norms in private and public life and taught them to their children, who have taken the mantle of their elders to push the struggle forward. The hardliners now want to halt that forward march.

This is the story of women’s “non-movement”—the collective and connective actions of non-collective actors who pursue not a politics of protest but of redress, through direct actions. Its aim is not a deliberate defiance of authorities but to establish alternative norms and life-making practices—practices that are necessary for a desired and dignified life but are denied to women. It is a slow but steady process of incremental claim-making that ultimately challenges the patriarchal-political authority.4 And now, that very “non-movement,” impelled by the murder of one of its own, Mahsa Amini, has given rise to an extraordinary political upheaval in which woman and her dignity, indeed human dignity, has become a rallying point.

Reclaiming Life

Today, the uprising is no longer limited to the mandatory hijab and women’s rights. It has grown to include wider concerns and constituencies—young people, students and teachers, middle-class families and workers, residents of some rural and poor communities, and those religious and ethnic minorities (Kurds, Arabs, Azeris, and Baluchis) who, like women, feel like second-class citizens and seem to identify with “Woman, Life, Freedom.” For these diverse constituencies, Mahsa Amini and her death embody the suffering that they have endured in their own lives—in their stolen youth, suppressed joy, and constant insecurity; in their poverty, debt, and drought; in their loss of land and livelihoods.

The thousands of tweets describing why people are protesting point time and again to the longing for a humble normal life denied to them by a regime of clerical and military patriarchs. For these dissenters, the regime appears like a colonial entity—with its alien thinking, feeling, and ruling—that has little to do with the lives and worldviews of the majority. This alien entity, they feel, has usurped the country and its resources, and continues to subjugate its people and their mode of living. “Woman, Life, Freedom” is a movement of liberation from this internal colonization. It is a movement to reclaim life. Its language is secular, wholly devoid of religion. Its peculiarity lies in its feminist facet.

But the feminism of the movement is not antagonistic to men. Rather, it embraces the subaltern, humiliated, and suffering men. Nor is this feminism reducible to the control of one’s body and the forced hijab—many traditional veiled women also identify with “Woman, Life, Freedom.” The feminism of the movement, rather, is antisystem; it challenges the systemic control of everyday life and the women at its core. It is precisely this antisystemic feminism that promises to liberate not only women but also the oppressed men—the marginalized, the minorities, and those who are demeaned and emasculatedby their failure to provide for their families due to economic misfortune. “Woman, Life, Freedom,” then, signifies a paradigm shift in Iranian subjectivity—recognition that the liberation of women may also bring the liberation of all other oppressed, excluded, and dejected people. This makes “Woman, Life, Freedom” an extraordinary movement.

Movement or Moment

Extraordinary yes, but is this a movement or a passing moment? Postrevolution Iran has witnessed numerous waves of nationwide protests. But this current episode seems fundamentally different. The Green revolt of 2009 was a powerful prodemocracy drive for an accountable government. It was largely a movement of the urban middle class and other discontented citizens. Almost a decade later, in the protests of 2017, tens of thousands of Iranian workers, students, farmers, middle-class poor, creditors, and women took to the streets in more than 85 cities for ten days before the government’s crackdown halted the rebellion.5 Some observers at the time considered the events a prelude to revolution. They were not. For although connected and concurrent, the protests were mostly concerned with sectoral claims—delayed wages for workers, drought for farmers, lost savings for creditors, and jobs for the young. As such, theirs was not a collective action of a united movement but connective actions of parallel concerns—a simultaneity of disparate protest actions that only the new information technologies could facilitate.A larger uprising in December 2019, which was triggered by a 200 percent rise in the price of gasoline, did see a measure of collective action, as different protesting groups—in particular the urban poor and the middle-class poor as well as the educated unemployed and underemployed—displayed a good degree of unity. Their central grievances concerned not only cost-of-living issues but also the absence of any prospects for the future. The protesters came largely from the marginalized areas of the cities and the provinces and followed radical tactics such as setting banks and government offices on fire and chanting antiregime slogans.

The current uprising has gone substantially further in message, size, and make-up. It has taken on a qualitatively different character and dynamics. This uprising has brought together the urban middle class, the middle-class poor, slum dwellers, and different ethnicities, including Kurds, Fars, Lors, Azeri Turks, and Baluchis—all under the banner of “Woman, Life, Freedom.” A collective claim has been created—one that has united diverse social groups to not only feel and share it, but also to act on it. With the emergence of the “people,” a super-collective in which differences of class, gender, ethnicity, and religion temporarily disappear in favor of a greater good, the uprising has assumed a revolutionary character. The abolition of the morality police and the mandatory hijab will no longer suffice. For the first time, a nationwide protest movement has called for a regime change and structural socioeconomic transformation.

Does all this mean that Iran is on the verge of another revolution? At this point in time, Iran is far from a “revolutionary situation,” meaning a condition of “dual power,” where an organized revolutionary force backed by millions would come to confront a crumbling government and divided security forces. What we are witnessing today, however, is the rise of a revolutionary movement—with its own protest repertoires, language, and identity—that may open Iranian society to a “revolutionary course.”

In the first three months after Mahsa Amini’s death, two-million Iranians from all walks of life staged some 1,200 protest actions that spilled over 160 cities and small towns. Friday prayer sermons in the poor province of Sistan and Baluchistan, as well as funerals and burials for victims of the regime’s crackdown in Kurdistan, have brought the most diverse crowds into the streets. University and high-school students have staged sit-ins, defied the mandatory hijab and sex segregation, and performed other courageous acts of resistance, while lawyers, professors, teachers, doctors, artists, and athletes expressed public support and sometimes joined the dissent.6 In cities and small towns, political graffiti decorated building walls before being repainted by municipality agents. The evening chants from balconies and rooftops in the residential neighborhoods continued to reverberate in the dark sky of the cities.

Security forces were frustrated by a mode of protest that combined street showdowns and guerrilla tactics—the sudden and simultaneous outbreak of multiple evening demonstrations in different urban quarters able to disappear, regroup, and reappear again. The fearlessness of these street rebels, many of them young women, overwhelmed the authorities. A revealing video of a security agent showed his astonishment about backstreet young protesters who “are no longer afraid of us” and the neighbors who “attack us with a barrage of rocks, chairs, benches, flowerpots,” or anything heavy from their windows or balconies.7

The disproportionate presence of the young—women and men, university and high school students—in the streets of the uprising has led some to interpret it as the revolt of Generation Z against a regime that is woefully out of touch. But this view overlooks the dissidence of older generations, the parents and families that have raised, if not politicized, these children and mostly share their sentiments. A leaked government survey from November 2022 found that 84 percent of Iranians expressed a positive view of the uprising.8 If the regime allowed peaceful public protests, we would likely see more older people on the streets. But it has not. The extraordinary presence of youth in the street protests has largely to do with the “youth affordances”—that is, energy, agility, education, dreams of a better future, and relative freedom from family responsibilities—which make the young more inclined to street politics and radical activism. But these extraordinary young people cannot cause a political breakthrough on their own. The breakthrough comes only when ordinary people—parents, children, workers, shopkeepers, professionals, and the like—join in to bring the spectacular protests into the social mainstream.

Although some workers have joined the protests through demonstrations and labor strikes, a widespread labor showdown has yet to materialize. This may not be easy, because the neoliberal restructuring of the 2000s has fragmented the working class, undermined workers’ job security (including in the oil sector), and diminished much of their collective power. In their place, teachers have emerged as a potentially powerful dissenting force with a good degree of organization and protest experience. On 14 February 2023, twenty civil and professional associations, led by the teachers’ syndicate, issued a joint “charter of minimum demands” that included the release of all political prisoners, free speech and assembly, abolition of the death penalty, and “complete gender equality.”9 Shopkeepers and bazaar merchants have also joined the opposition. In fact, they surprised the authorities when at least 70 percent of them, according to a leaked official report, went on strike in Tehran and 21 provinces on 15 November 2022 to mark the 2019 uprising.10 Not surprisingly, security forces have increasingly been threatening to shut down their businesses.

The Regime’s Response

The regime is acutely aware and apprehensive of the power of the social mainstream. It has made every effort to prevent mass congregations on the scale of Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring when protesters could see, feel, and show the rulers the enormity of their social power. Protesters in the Arab Spring fully utilized existing cultural resources, such as religious rituals and funeral processions, to sustain mass protests. Most critical were the Friday prayers, with their fixed times and places, from which the largest rallies and demonstrations originated. But Friday prayer is not part of the current culture of Iran’s Shia Muslims (unlike the Sunni Baluchies). Most Iranian Muslims rarely even pray at noon, whether on Fridays or any day. In Iran, the Friday prayer sermons are the invented ritual of the Islamist regime and thus the theater of the regime’s power. Consequently, protesters would have to turn to other cultural and religious spaces such as funerals and mourning ceremonies or the Shia rituals of Moharram and Ramadan.

But the clerical regime would not hesitate to prohibit even the most revered cultural and religious traditions if it deemed them a threat to the “system.” During the Green revolt of 2009, the ruling hardliners banned funerals and prevented families from holding mourning ceremonies for their loved ones. On occasion, authorities even prohibited Shia rituals. This is not surprising. Ayatollah Khomeini, the Islamic Republic’s founding father, had already decreed that the supreme faqih held “absolute authority” to disregard any precept or law, including the constitution or religious obligations such as daily prayers “in the interest of the state.”11 Iran’s clerical rulers would not hesitate to prohibit these cultural and religious rituals, precisely because of their exclusive claim on them. Under this perverse authority, the regime would delegitimize and discard values and practices from which it derives its own legitimacy. For it views itself as the sole legitimate body able to determine what is sacred and what is sin, what is authentic, what is fake, what is right, and what is wrong.

For the regime agents,mass demonstrations of spectacular scale would sound the call of revolution. They do not wish to hear it but cannot help feeling it. For a hum and whisper of revolution is already in the air. It can be heard and felt in homes, at private gatherings, and in the streets; in the rich body of art, literature, poetry, and music borne of the uprising; and in the media and intellectual debates about the meaning of the current moment, organization and strategy, the question of violence, and the way forward.12 The regime has responded with denial, ridicule, anger, appeasement, and widespread violence.

The daily Keyhan, close to the office of the supreme leader, has charged the protesters with wanting to establish “forced de-veiling” and warned that the “Islamic revolution will not go away. . . . So, be angry and die of your fury.”13 The commanders of the key security forces—the military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the Basij militia, and the police—issued a joint statement on 5 October 2022 declaring their loyalty to the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. And the hardline parliament passed an emergency bill on 9 October 2022 “adjusting” the salaries of civil servants, including 700,000 pensioners who in late 2017 had turned out in force during a wave of protests. Newly employed teachers were to receive more secure contracts, sugarcane workers their unpaid wages, and poor families a 50 percent increase in the basic-needs subsidy. Meanwhile, the speaker of the parliament, Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, confirmed that he was prepared to implement “any reform and change for public interest,” including “change in the system of governance” if the protesters abandoned demands for “regime change.”14

Appeasing the population with “salary adjustments” and fiscal measures has gone hand-in-hand with a brutal repression of the protesters. This includes beating, killing, mass detention, torture, execution, drone surveillance, and marking the businesses and homes of dissenters. The regime’s clampdown has reportedly left 525 dead, including 71 minors, 1,100 on trial, and some 30,000 detained. The security forces and Basij militia have lost 68 members in the unrest.15 The regime blames “hooligans” for causing disorder, the internet for misleading the youth, and the Western governments for plotting to topple the government.

A Revolutionary Course

The regime’s suppression and the protesters’ pauseare likely to diminish the protests. But this does not mean the end of the movement. It means the end of a cycle of protest before a trigger ignites a new one. We have seen these cycles at least since 2017. What is distinct about this time is that it has set Iranian society on a “revolutionary course,” meaning that a large part of society continues to think, imagine, talk, and act in terms of a different future. Here, people’s judgment about public matters is often shaped by a lingering echo of “revolution” and a brewing belief that “they [the regime] will go.” So, any trouble or crisis—for instance, a water shortage—is considered a failure of the regime, and any show of discontent—say, over delayed wages—a revolutionary act. In such a mindset, the status quo is temporary and change only a matter of time. Consequently, intermittent periods of calm and contention could continue to possibly evolve into a revolutionary situation. We have witnessed such a revolutionary course before—in Poland, for instance, after martial law was declared and the Solidarity movement outlawed in 1982 until the military regime agreed to negotiate a transition to a new order in 1988. More recently, Sudan experienced a similar course after the dictator Omar al-Bashir declared a state of emergency and dissolved the national and regional governments in February 2019 until the military signed an agreement on the transition to civilian democratic rule with the opposition Forces of Freedom and Change after seven months.

Only radical political reform and meaningful improvement in people’s lives can disrupt a revolutionary course. For instance, holding a referendum about the form of government, changing the constitution to be more inclusive, or implementing serious social programs can dissuade people from seeking regime change. Otherwise, one should expect either a state of perpetual crisis and ungovernability or a possible move toward a revolutionary situation. But a revolutionary situation is unlikely until the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement grows into a credible alternative, a practical substitute, to the incumbent regime. A credible alternative means no less than a leadership organization and a strategic vision capable of garnering popular confidence. It means a collective force, a tangible entity, that is able to embody a coalition of diverse dissenting groups and constituencies and to articulate what kind of future it wants.

There are, of course, local leaders and ad hoc collectives that communicate ideas and coordinate actions in the neighborhoods, workplaces, and universities. Thanks to their horizontal, networked, and fluid character, their operations are less prone to police repression than a conventional movement organization would be. This kind of decentralized networked activism is also more versatile, allows for multiple voices and ideas, and can use digital media to mobilize larger crowds in less time. But networked movements can also suffer from weaker commitment, unruly decisionmaking, and tenuous structure and sustainability. For instance, who will address a wrongdoing, such as violence, committed in the name of the movement? As a result, movements tend to deploy a hybrid structure by linking the decentralized and fluid activism to a central body. The “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement has yet to take up this consideration.

Civil society and imprisoned activists who currently enjoy wide recognition and respect for their extraordinary commitment and political intelligence may eventually form a kind of moral-intellectual leadership. But that too needs to be part of a broader national leadership organization. For a leadership organization—in the vein of Polish Solidarity, South Africa’s ANC, or Sudan’s Forces of Freedom and Change—is not just about articulating a strategic vision and coordinating actions. It also signals responsibility, representation, popular trust, and tactical unity.

This is perhaps the most challenging task ahead for “Woman, Life, Freedom,” but remains acutely indispensable. Because, first, a political breakthrough is unlikely without a broad-based organized opposition. Second, a negotiated transition to a new political order is impossible in the absence of a leadership organization. Who is the incumbent supposed to negotiate with if there is no representation from the opposition? And third, if political collapse occurs and there is no credible organized alternative to an incumbent regime, other organized, entrenched, and opportunistic forces—for example, the military, political parties, sectarian groups, or religious organizations—will move in to shape the course and outcome of a transition. Such forces could claim to represent the opposition and make unwanted deals or might simply fill the power vacuum when authority collapses. Hannah Arendt was correct in observing that the collapse of authority and power becomes a revolution “only when there are people willing and capable of picking up the power, of moving into and penetrating, so to speak, the power vacuum.”16 In other words, if the revolutionary movement is unwilling or unable to pick up the power, others will. This, in fact, is the story of most of the Arab Spring uprisings—Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and Yemen, for instance. In these experiences, the protagonists, those who had initiated and carried the uprisings forward, remained mostly marginal to the process of critical decisionmaking while the free-riders, counterrevolutionaries, and custodians of the status quo moved to the center.17

No one knows where exactly the uprising in Iran will lead. Thus far, the ruling circle remains united even though signs of doubt and discord have appeared within the lower ranks.18 The traditional leaders and grand ayatollahs have mostly stayed silent. But reformist groups have increasingly been voicing their dissent, urging the rulers to undertake serious reforms to restore calm. None of them say that they want a regime change, but they seem to see themselves mediating a transition should such a time arrive. Former president Mohammad Khatami has admitted that the reformist path which he championed has reached a dead end, yet finds the remedy for the current crisis in amending and enforcing the constitution. But a growing number of reformist figures, led by former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi, are calling for a referendum and a new constitution. The hardline rulers, however, remain defiant and show no sign of revisiting their policies let alone undertaking serious reforms. Resting on the support of their “people on the stage,” they aim to hold on to power through pacification, control, and coercion.19

NOTES

1. Azam Khatam, “Street Politics and Hijab in the ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ Movement,” Naqd-e Eqtesad-e Siyasi, 12 November 2022, in Persian.

2. Danny Postel, “Iran’s Role in the Shifting Political Landscape of the Middle East,” New Politics, 7 July 2021, https://newpol.org/the-other-regional-counter-revolution-irans-role-in-the-shifting-political-landscape-of-the-middle-east/.

3. A woman’s letter to Zanan, no. 35 (June 1988), 26.

4. For a detailed discussion of “non-movements,” see Asef Bayat, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013). For an elaboration of how “non-movements” may merge into larger movements and revolutions, see Asef Bayat, Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021).

5. Asef Bayat, “The Fire That Fueled the Iran Protests,” Atlantic, 27 January 2018, www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/iran-protest-mashaad-green-class-labor-economy/551690.

6. Miriam Berger, “Students in Iran Are Risking Everything to Rise Up Against the Government,” Washington Post, 5 January 2023; Deepa Parent and Anna Kelly, “Iranian Schoolgirl ‘Beaten to Death’ for Refusing to Sing Pro-Regime Anthem,” Guardian, 18 October 2022; Celine Alkhaldi and Adam Pourahmadi, “Iranian Teachers Call for Nationwide Strike in Protest over Deaths and Detention of Students,” CNN, 21 October 2022.

7. Video clip circulated on social media of the speech of a security agent, Syed Pouyan Hosseinpour, at the 31 October 2022 funeral ceremony of a Basij member killed during the protests.

8. According to a leaked confidential bulletin of Fars News Agency and a government survey, reported on the Radio Farda website, 30 November 2022, www.radiofarda.com/a/black-reward-files/32155427.html.

9. Radio Farda, 15 February 2023; www.radiofarda.com/a/the-minimum-demands-of-independent-organizations-in-iran-were-announced/32272456.html

10. Reported in a leaked audio of a security official, Qasem Ghoreishi, speaking to a group of journalists from the Pars News Agency, close to the Revolutionary Guards. Reported also on the Khabar Nameh Gooyawebsite on 29 December 2022.

11. Asghar Schirazi, The Constitution of Iran: Politics and the State in the Islamic Republic (London: I.B. Tauris, 1998).

12. For a discussion on poetry, see www.radiozamaneh.com/742605/.

13. Keyhan, editorial, 6 October 2022.

14. Khabarbaan, 23 October 2022, https://36300290.khabarban.com/.

15. Iranian Organization of Human Rights, Hrana, www.hra-news.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Mahsa-Amini-82-Days-Protest-HRA.pdf; https://twitter.com/hra_news/status/1617296099148025857/photo/1. The number of 30,000 detainees is based on a leaked official document reported in Rouydad 24, 28 January, www.rouydad24.ir/fa/news/330219/%D9%87%D8%B2%DB%8C%D9%86%D9%87-%D9%87%D8%B1-%D8%B2%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%A7%D9%86%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%DA%86%D9%82%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA.

16. Hannah Arendt, “The Lecture: Thoughts on Poverty, Misery and the Great Revolutions of History,” New England Review,June 2017, 12, available athttps://lithub.com/never-before-published-hannah-arendt-on-what-freedom-and-revolution-really-mean/.

17. This predicament resulted partly from the “refo-lutionary” character of the Arab Spring. “Refo-lution” refers to the revolutionary movements that emerge to compel the incumbent regimes to reform themselves on behalf of revolution, without picking up the power or intervening effectively in shaping the outcome. See Asef Bayat, Revolution without Revolutionaries: Making Sense of the Arab Spring (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this date in history:

In 323 B.C., Alexander the Great died of fever in Babylon at age 33.

In 1910, former President Theodore Roosevelt cured a severe case of seasickness which overcame his daughter Ethel's dog, Bongo.

In 1944, the first German V-1 "buzz bomb" hit London.

In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Miranda vs. Arizona, ruled that police must inform all arrested people of their constitutional rights before questioning them.

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Thurgood Marshall to the Supreme Court. He became the first African American on the high court in August.

In 1971, The New York Times began publishing top secret, sensitive details and documents from 47 volumes that comprised the history of the U.S. decision making process on Vietnam policy, better known as the Pentagon Papers. Daniel Ellsberg, a former U.S. military analyst, leaked the documents to Times reporter Neil Sheehan.

In 1976, Arizona Republic investigative reporter Don Bolles died as a result of injuries suffered when a bomb blew up his car 11 days earlier. He had been working on an organized crime story at the time of his death.

In 1977, James Earl Ray, convicted assassin of Martin Luther King Jr., was captured in a Tennessee wilderness area after escaping from prison.

In 1983, the robot spacecraft Pioneer 10 became the first man-made object to leave the solar system. It did so 11 years after it was launched.

In 1993, Canada got its first female prime minister when the ruling Progressive Conservative Party elected Kim Campbell to head the party and thus the country.

In 1994, Nicole Brown Simpson, the ex-wife of former football star O.J. Simpson, and her friend Ronald Goldman were found stabbed to death outside her condominium in the Brentwood section of Los Angeles. Simpson was charged with the murders and acquitted in a trial that became a media sensation. A civil court later found him liable in a wrongful-death lawsuit and, in an unrelated robbery case in Nevada, he was convicted in 2008 and sentenced to 33 years in prison.

In 1996, members of the Freeman militia surrendered, 10 days after the FBI cut off electricity to their Montana compound. The standoff lasted 81 days.

In 2000, South Korean President Kim Dae-jung and North Korean leader Kim Jong Il meet for the first-ever inter-Korea summit in Pyongyang.

In 2005, pop superstar Michael Jackson was acquitted by a California jury on charges of child molestation.

In 2009, incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was declared the winner in a disputed Iranian presidential election, touching off widespread clashes between protesters and police.

In 2011, the complete Pentagon Papers, a secret history of the Vietnam War, were made public 40 years after the first leaks were published. The excerpts leaked by Daniel Ellsberg led to a battle with the Nixon administration and a landmark ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court expanding freedom of the press.

In 2012, ousted Tunisian President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, in exile and tried in absentia, was sentenced to life imprisonment for ordering the shooting of protesters.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that human genes cannot be patented.

In 2020, Atlanta police chief Erika Shields resigned after the death of Rayshard Brooks, a Black man, at the hands of a police officer. The officer who shot Brooks, Garrett Rolfe, was fired, but reinstated in May 2021.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 12.27 (after 1940)

1945 – The International Monetary Fund is created with the signing of an agreement by 29 nations.

1949 – Indonesian National Revolution: The Netherlands officially recognizes Indonesian independence. End of the Dutch East Indies.

1966 – The Cave of Swallows, the largest known cave shaft in the world, is discovered in Aquismón, San Luis Potosí, Mexico.

1968 – Apollo program: Apollo 8 splashes down in the Pacific Ocean, ending the first orbital crewed mission to the Moon.

1968 – North Central Airlines Flight 458 crashes at O'Hare International Airport, killing 28.

1978 – Spain becomes a democracy after 40 years of fascist dictatorship.

1983 – Pope John Paul II visits Mehmet Ali Ağca in Rebibbia's prison and personally forgives him for the 1981 attack on him in St. Peter's Square.

1985 – Palestinian guerrillas kill eighteen people inside the airports of Rome, Italy, and Vienna, Austria.

1989 – The Romanian Revolution concludes, as the last minor street confrontations and stray shootings abruptly end in the country's capital, Bucharest.

1991 – Scandinavian Airlines System Flight 751 crashes in Gottröra in the Norrtälje Municipality in Sweden, injuring 92.

1996 – Taliban forces retake the strategic Bagram Airfield which solidifies their buffer zone around Kabul, Afghanistan.

1997 – Protestant paramilitary leader Billy Wright is assassinated in Northern Ireland, United Kingdom.

2002 – Two truck bombs kill 72 and wound 200 at the pro-Moscow headquarters of the Chechen government in Grozny, Chechnya, Russia.

2004 – Radiation from an explosion on the magnetar SGR 1806-20 reaches Earth. It is the brightest extrasolar event known to have been witnessed on the planet.

2007 – Former Pakistani prime minister Benazir Bhutto is assassinated in a shooting incident.

2007 – Riots erupt in Mombasa, Kenya, after Mwai Kibaki is declared the winner of the presidential election, triggering a political, economic, and humanitarian crisis.

2008 – Operation Cast Lead: Israel launches three-week operation on Gaza.

2009 – Iranian election protests: On the Day of Ashura in Tehran, Iran, government security forces fire upon demonstrators.

2019 – Bek Air Flight 2100 crashes during takeoff from Almaty International Airport in Almaty, Kazakhstan, killing 13.

0 notes

Text

Iranian Women you Should Know: Simin Behbahani

Simin Behbahani was a poet, writer, human rights and women rights activist, and a founder of the Iranian Writers' Association, an affiliate of International PEN. She was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature twice, in 1999 and 2002. In 2009, Behbahani received the Simone de Beauvoir Prize for Women's Freedom on behalf of women's rights campaigners in Iran.

Among her many admirers, Behbahani, who died in August 2014, was known as the “lioness of Iran.”

The Iranian Writers’ Association started its activities in 1968 under Iran’s Pahlavi dynasty and was the first professional association for writers in Iran. While writers did not have an easy time under the Shah, since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, members of the association have faced harassment, prison, torture, exile and, of course, censorship. Over a 10-year period, from 1988-1998, intellectuals were targeted in a series of extrajudicial killings that became known as “Chain Murders.” Two of the writers’ association members, Mohammad Mokhtari and Mohammad Jafar Pouyandeh, were murdered, and there were attempts on the lives of a number of others.

Simin Behbahani was born in June 1927 to a literary family. Her father, Abbas Khalili, was a poet, writer and newspaper editor. Her mother, Fakhr Ozma Arghun, was a poet and a member of the progressive Association of Patriotic Women between 1925 and 1929.

Behbahani started writing poetry at 12 and published her first collection when she was 14.

In 1958, she began studying law at Tehran University, but after graduation, she preferred teaching over practicing law.

Before the revolution, Behbahani also wrote lyrics for popular Iranian singers, and she sat on the Iranian National Radio and TV’s Music Council. Themes of patriotism, poverty, freedom of expression and women’s rights run through her lyrics and poetry.

In the summer of 1988, when the Islamic Republic executed countless number of political prisoners without returning their bodies to their families or informing them where they were buried, Simin Behbahani published a poem dedicated to the victims’ mothers.

When police forces gunned down a young woman, Neda Agha Soltan, during the protests that followed the disputed 2009 presidential election, Behbahani dedicated a poem in Soltan’s memory: “Dead you are not, dead you will not be/Always you will live, live with eternal life/You embody the people’s call [Neda].”

On March 20, 2011, to mark the Iranian new year, US President Barak Obama issued a message to the people of Iran, quoting Simin Behbahani: “Old, I may be, but, given the chance, I will learn. I will begin a second youth alongside my progeny. I will recite the Hadith of love of country with such fervor as to make each word bear life.” Obama called Behbahani “a woman who has been banned from traveling beyond Iran, even though her words have moved the world.”

Behbahani’s protests were not limited to her poetry. She participated in rallies supporting causes important to her. Once security agents beat her during a protest staged by women in Daneshjou Park. And when women staged a sit-in in front of parliament to protest against legislation that they believed trampled on their rights, she joined them despite her advanced years.

Behbahani received several awards for her activities in support of human rights, including the 1998 Human Rights Watch Hellman-Hammet Grant and the 2006 Norwegian Authors' Union Freedom of Expression Prize.

In March 2010, she planned to travel to Paris for necessary medical treatment and to deliver an address on the occasion of International Women’s Day. As she was about to board the plane for Paris, she was detained and interrogated throughout the night, although she was in her eighties and nearly blind. Her passport was seized and she was banned from traveling abroad.

Behbahani died at the age of 87 on August 19, 2014 after spending 13 days in a coma. Literary figures and many young fans of her poetry attended her funeral, and social media websites were flooded with praise for her and celebration of her work. Official Islamic Republic radio and television did not even report her death, which was not unexpected, given that she was not a favorite of the Islamic Republic regime, especially among hardliners. Jahan News, a hardline Iranian website, once characterized Behbahani’s writing as treasonous: “Her poetry, with its slanderous and scandalous way of addressing Iranians, only serves to make Iran’s enemies happy.”

But as long as she was alive, Behbahani did not stop defending the undefended and standing up against injustice.

For millions of Iranians inside the country and abroad, Simin Behbahani was the “eloquent voice of conscience,” according to Farzaneh Milani, a scholar of Persian literature at the University of Virginia. “She was the elegant voice of dissent, of conscience, of non-violence, of the refusal to be ideological.”

Realated articles:

A Poet Who Stayed, A Nation’s Conscience

0 notes

Text

14 years ago : Clotilde Reiss jailed in Iran

Clotilde Reiss, a French citizen, was arrested during the protests after the 2009 Iranian presidential elections.

Ms. Reiss, who holds a master’s from Sciences-Po Lille, spent nine months in an Iranian prison. She was eventually released after posting a $280,00 bail.

Reiss’s return to Paris coincided with the French authorities releasing Majid Kakavand, an Iranian engineer accused of buying…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Iranian rock climber Elnaz Rekabi says hijab inadvertently fell off throughout competitors in South Korea

Iranian rock climber Elnaz Rekabi, who competed at an occasion with out sporting a compulsory headband, has launched a message on social media for the primary time since issues had been raised for her security.

Key factors:

The Instagram story mentioned she competed with no hair protecting as a result of it unintentionally fell off

She apologised for “getting everybody frightened” and mentioned she was flying residence to Iran

The BBC reported Elnaz Rekabi left South Korea a day sooner than scheduled

Rekabi, 33, a a number of medallist, mentioned in a put up on her Instagram story on Tuesday that she competed with no hair protecting as a result of her hijab had “inadvertently” fallen off throughout the competitors in South Korea.

Within the Instagram story, she apologised for “getting all people frightened”.

“On account of dangerous timing, and the unanticipated name for me to climb the wall, my head protecting inadvertently got here off,” the story mentioned, in response to a translation from the BBC.

It mentioned that she could be flying residence to Iran “alongside the group based mostly on the pre-arranged schedule”

It’s not clear whether or not the put up was written below duress.

Rekabi’s show with no hijab got here as protests rang out throughout Iran towards the loss of life of Mahsa Amini, who was detained by the nation’s morality police over her clothes and died in custody.

The demonstrations, drawing a variety of Iranians, signify essentially the most severe problem to Iran’s theocracy because the mass protests surrounding its disputed 2009 presidential election.

Elnaz Rekabi competed at a mountaineering competitors in South Korea.(Instagram: elnaz.rekabi/File)

Human rights teams say tons of of individuals have been killed as safety forces crack down on the protests.

The BBC, quoting unnamed “knowledgeable supply”, reported that Rekabi’s cell phone and passport had been seized and her buddies had been unable to contact her since she competed.

Rekabi left Seoul on a Tuesday morning flight, the Iranian embassy in South Korea mentioned, though she was initially scheduled to return on Wednesday, in response to BBC Persian.

IranWire alleged that Rekabi could be transferred to Tehran’s infamous Evin Jail — which was the location of a large hearth this week that killed eight prisoners — after arriving within the nation.

In a tweet, the Iranian embassy in Seoul denied “all of the faux, false information and disinformation” relating to Rekabi’s departure on Tuesday.

However as a substitute of posting a photograph of her from the Seoul competitors, it posted a picture of her sporting a scarf at a earlier competitors in Moscow, the place she additionally took a bronze medal.

Area to play or pause, M to mute, left and proper arrows to hunt, up and down arrows for quantity.

Watch

Period: 5 minutes 48 seconds5m

Considerations for Iranian rock climber who competed with out headband.

ABC/AP

Originally published at Sunshine Coast QLD News

0 notes

Text

Emails: Hillary Clinton plotted with Qatar to establish $100M ‘Voice of America’-like media channel for the Muslim Brotherhood

Hillary Clinton and Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi in 2012

The recent exposure of Hillary Clinton’s emails is arousing resentment in the Arab media in moderate countries as they demonstrate her apparent support for extreme Muslim elements in the Middle East and the chaos caused by the so-called Arab Spring.

Some of the emails from former US Secretary of State Clinton that were recently released as part of President Donald Trump’s election campaign apparently reveal direct American involvement in the Arab Spring events and a deep connection between the Obama administration and Qatar that included a joint effort to establish a media channel and an economic fund to be used by the Muslim Brotherhood as a means of intervention in Arab countries in the region.

One of the emails reveals a plan between Clinton and the Qatari government to establish a media channel with initial funding of $100 million. This plan followed complaints from the Muslim Brotherhood about the weakness of their media system compared to other media outlets.

The idea was to establish a communication channel run by the Muslim Brotherhood and similar to the Voice of America.

The emails revealed that the intention was to place Khairat el-Shater, a senior member of the Muslim Brotherhood and an Islamist activist who ran for president in Egypt, at the head of the media channel and entrust him with the $100 million.

The emails also reveal the depth of the connection between Clinton and the Obama administration and the Qatari Al Jazeera channel as a propaganda mouthpiece that supports political Islam organizations and encourages chaos in Arab countries.

Among other things, it appears that Clinton acted to market a positive image of President Barak Obama through Al Jazeera and portray him as a supporter of Muslim communities.

The emails indicate that Clinton met with the heads of Al Jazeera at the Four Seasons Hotel in Doha, Qatar, during a quick visit that left her no time to visit an American base there. Clinton met the American officers for a brief meeting, after a meeting between her and the directors of Al Jazeera.

The meeting was also attended by senior Qatari government officials and also included the possibility of a reciprocal Qatari visit to the United States.

The exchange of messages shows that Clinton sought to take advantage of the channel and broadcast a 15-minute program in Arabic that would emphasize the Obama administration’s commitment to Muslim communities around the world.

Clinton also asked to meet with Qatari journalists for a discussion on the relationship between the Obama administration and Qatar.

Another issue that emerges from the emails is the launch of an Egyptian-American investment fund, which was also intended to operate in Tunisia, for economic and welfare purposes. Jim Harmon, an American banker close to Obama, was elected to head the fund, but alongside the first $60 million from Egypt, Qatar had pledged a $2 billion aid package to Egypt.

The emails indicate that the Qataris had sought to use the fund to intervene in the affairs of Egypt and Tunisia with money derived from the Muslim Brotherhood’s patronage. One of the emails reveals that Harmon urged Qataris to join the American effort in this matter.

The emails also reveal that in July 2009, one of the US State Department officials met with senior Hamas figures Mahmoud Al-Zahar and Bassem Naim for a meeting in Switzerland, which was also attended by the US Ambassador to the United Nations Thomas Pickering. At the end of the meeting, Naim expressed hopes that it was the beginning of the correction of the injustice that lasted in the three years prior to the meeting.

Another email reveals that Saud bin Faisal, the former Saudi foreign minister, hung up the phone on Clinton when she demanded he not send troops to Bahrain in 2011. It should be noted that the Saudis then acted to save the Bahraini regime from a so-called popular uprising inspired by Shiite organizations affiliated with the Iranian regime.

There are articles in the Arab media stating that the emails are further evidence of the Obama administration’s volatility and lack of support for the Arab regimes alongside incomprehensible support for extremist movements and political Islam.

Articles in the Arab media attack US presidential candidate Joe Biden, stating that he “belongs to the same rotten tree” and that if he wins the world will witness far more serious events than the events of 2011 and the Arab Spring, which the Obama administration promoted as if they were spontaneous popular uprisings.

Articles claim that the email affair exposes Obama’s destructive role and the depth of his ties to Qatar and the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as Al Jazeera’s assistance in these efforts.

The various testimonies indicate that Clinton pulled the strings of the so-called Arab Spring though she knew it was not a spontaneous event and helped promote them through the investment fund as well.

“This is a testament to Obama’s dark chapter,” read one of the Arab articles, “a testimony to American support for political Islam and chaos.”

An article also notes that Biden at the time opposed bin Laden’s assassination.

The Clinton email affair was at the center of the 2016 election in the US, helping Donald Trump to portray his rival as corrupt and unfit for office.

Since then, Trump has been raising the issue and demanding the emails be exposed. Trump expressed frustration that current Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has so far failed to release some of the classified emails and expressed dissatisfaction with him, prompting Pompeo to promise to disclose the emails.

--------------------------------

More via:

Leaked emails: Obama administration’s support to Muslim Brotherhood to dominate media

CAIRO – 12 October 2020: On Thursday, US President Donald Trump expressed displeasure that his Secretary of State had not yet released some emails related to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. A day later, Pompeo vowed to release them.

Arab and Gulf media have later focused on these emails, which are not new, revealing a relation between the US, during the term of former President Barack Obama, and Qatari Al Jazeera as well as the Muslim Brotherhood group.

The emails bring back to mind the role Clinton played in supporting the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood group to reach power and the exposure of the group’s plan at that time to control the media platforms to broadcast its intellectual project.

One of the leaked mails

The outlawed group targeted all high-level state positions, including ministries, and attempted to fully control the Egyptian media, so it launched pro-Muslim Brotherhood channels, broadcast from inside and outside the country.

The group knew that controlling media cannot be achieved except by controlling the building of the Egyptian Radio and Television Union, aka Maspero, the official broadcast building of the Egyptian state.

As a result, the group appointed notorious Salah Abdel-Maqsoud as the information minister.

Abdel Maqsoud was accused of committing three incidents of verbal sexual harassment of female journalists and media figures, during his term.

This prompted female journalists to launch a campaign to remove him from his post, and they submitted a petition to Mohamed Morsi, at the time, to pressure him to dismiss Abdel Maqsoud, but he did not care until the revolution broke out in 2013.

The group also tried to dominate a number of national press institutions by pushing a number of their affiliates to head these institutions.

This caused a number of major writers in independent newspapers to abstain from writing articles, in protest at what they saw as an attempt by the group to control the national media.

This situation continued until the June 30 Revolution in 2013 ousted the president and caused the group to be designated as terrorist.

Al Jazeera

Wadah Khanfar, former director of the Al Jazeera network, appeared in emails with Clinton notifying her with all details taking place regarding the network known for its support to terrorist and extremist groups. The full and direct supervise of Clinton’s staff to Al Jazeera network and its skeptical coverage to the political events, raises a lot of question regarding the whole administration intentions towards the MENA region.

In one of the emails sent by Khanfar, he explains his own opinion of the escalating political events in number of Arab countries, urging the U.S. government to interfere to protect freedoms. These emails were just between the Former Secretary of State and Khanfar as no officials or government members were included in these emails.

One of the leaked mails

48 notes

·

View notes

Link

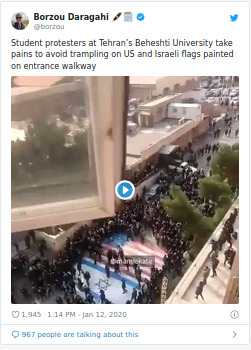

As anti-government protests swept Iran in the aftermath of the downing of a Ukrainian plane, students from Tehran avoided walking on massive American and Israel flags placed on the road in front of them.

Videos circulated on social media showed Iranian students parting as they approached the large flags, taking pains to avoid stepping on them. A few people who did walk over the flags were booed by protesters in the area with chants of "Shame on you."Some reports said that the protesters near the flags chanted "Our enemy is in Iran, not America."

Hillel Neuer, the executive director of NGO UN Watch, tweeted in response "these courageous Iranian students who refuse to trample the U.S. & Israeli flags represent the hope for a better Middle East."Protests spread throughout Tehran and multiple other Iranian cities after the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) took responsibility on Saturday for the downing of a Ukrainian civilian airliner on Wednesday, killing all on board.Families of the Iranian victims from the Ukrainian plane have reportedly been warned not to speak to foreign media at risk of not receiving their relatives' bodies, according to Al-Arabiya. Similar threats to withhold relatives' bodies were used during anti-government protests in November.Robert Macaire, the British ambassador to Tehran, was arrested by security forces amid protesters in Tehran, but was released after a few hours, according to Radio Farda. The ambassador "began to provoke and organize the protesters and was arrested inside a shop after security forces became suspicious of him," according to the Iranian Tasnim news agency. He allegedly filmed the protests.British Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab stated on Saturday that Macaire's arrest "without grounds or explanation is a flagrant violation of international law.""The Iranian government is at a cross-roads moment. It can continue its march towards pariah status with all the political and economic isolation that entails, or take steps to deescalate tensions and engage in a diplomatic path forwards," added Raab.Informed sources told Iran International that civilian flights were allowed on the night of the IRGC's missile attack against US bases in Iraq as a "human shield measure."Videos of the protests showed demonstrators shouting with chants against Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the regime at large. Security forces are present and have used some anti-riot measures such as tear gas, but so far no casualties have been reported. Internet may have been shut off in some parts of Tehran. Some reports claimed that protesters in Tehran tore up pictures of former IRGC Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani.Former speaker of the Iranian Parliament Mehdi Karroubi told Khamenei in a letter that "Undoubtedly, you are not qualified for the leadership as is required by the Constitution," according to Radio Farda.Karroubi also blamed Khamenei for the suppression and murder of protesters in November, vote-rigging in the 2009 presidential elections and political chain murders from 1988-1998. Karroubi has been under house arrest since 2011.

70 notes

·

View notes

Link

Iran is experiencing its deadliest political unrest since the Islamic Revolution 40 years ago, with at least 180 people killed — and possibly hundreds more — as angry protests have been smothered in a government crackdown of unbridled force.

It began two weeks ago with an abrupt increase of at least 50 percent in gasoline prices. Within 72 hours, outraged demonstrators in cities large and small were calling for an end to the Islamic Republic’s government and the downfall of its leaders.

In many places, security forces responded by opening fire on unarmed protesters, largely unemployed or low-income young men between the ages of 19 and 26, according to witness accounts and videos. In the southwest city of Mahshahr alone, witnesses and medical personnel said, Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps members surrounded, shot and killed 40 to 100 demonstrators — mostly unarmed young men — in a marsh where they had sought refuge.

“The recent use of lethal force against people throughout the country is unprecedented, even for the Islamic Republic and its record of violence,” said Omid Memarian, the deputy director at the Center for Human Rights in Iran, a New York-based group.

Altogether, from 180 to 450 people, and possibly more, were killed in four days of intense violence after the gasoline price increase was announced on Nov. 15, with at least 2,000 wounded and 7,000 detained, according to international rights organizations, opposition groups and local journalists.

The last enormous wave of protests in Iran — in 2009 after a contested election, which was also met with a deadly crackdown — left 72 people dead over a much longer period of about 10 months.

Only now, nearly two weeks after the protests were crushed — and largely obscured by an internet blackout in the country that was lifted recently — have details corroborating the scope of killings and destruction started to dribble out.

The latest outbursts not only revealed staggering levels of frustration with Iran’s leaders, but also underscored the serious economic and political challenges facing them, from the Trump administration’s onerous sanctions on the country to the growing resentment toward Iran by neighbors in an increasingly unstable Middle East.

The gas price increase, which was announced as most Iranians had gone to bed, came as Iran is struggling to fill a yawning budget gap. The Trump administration sanctions, mostly notably their tight restrictions on exports of Iran’s oil, are a big reason for the shortfall. The sanctions are meant to pressure Iran into renegotiating the 2015 nuclear agreement between Iran and major world powers, which President Trump abandoned, calling it too weak.

Most of the nationwide unrest seemed concentrated in neighborhoods and cities populated by low-income and working-class families, suggesting this was an uprising born in the historically loyal power base of Iran’s post-revolutionary hierarchy.

Many Iranians, stupefied and embittered, have directed their hostility directly at the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who called the crackdown a justified response to a plot by Iran’s enemies at home and abroad.

The killings prompted a provocative warning from Mir Hussein Moussavi, an opposition leader and former presidential candidate whose 2009 election loss set off peaceful demonstrations that Ayatollah Khamenei also suppressed by force.

In a statement posted Saturday on an opposition website, Mr. Moussavi, who has been under house arrest since 2011 and seldom speaks publicly, blamed the supreme leader for the killings. He compared them to an infamous 1978 massacre by government forces that led to the downfall of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi a year later, at the hands of the Islamic revolutionaries who now rule the country.

“The killers of the year 1978 were the representatives of a nonreligious regime and the agents and shooters of November 2019 are the representatives of a religious government,” he said. “Then the commander in chief was the shah and today, here, the supreme leader with absolute authority.”

The authorities have declined to specify casualties and arrests and have denounced unofficial figures on the national death toll as speculative. But the nation’s interior minister, Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, has cited widespread unrest around the country.

On state media, he said that protests had erupted in 29 out of 31 provinces and 50 military bases had been attacked, which if true suggested a level of coordination absent in the earlier protests. The property damage also included 731 banks, 140 public spaces, nine religious centers, 70 gasoline stations, 307 vehicles, 183 police cars, 1,076 motorcycles and 34 ambulances, the interior minister said.

The worst violence documented so far happened in the city of Mahshahr and its suburbs, with a population of 120,000 people in Iran’s southwest Khuzestan Province — a region with an ethnic Arab majority that has a long history of unrest and opposition to the central government. Mahshahr is adjacent to the nation’s largest industrial petrochemical complex and serves as a gateway to Bandar Imam, a major port.

The New York Times interviewed six residents of the city, including a protest leader who had witnessed the violence; a reporter based in the city who works for Iranian media, and had investigated the violence but was banned from reporting it; and a nurse at the hospital where casualties were treated.

They each provided similar accounts of how the Revolutionary Guards deployed a large force to Mahshahr on Monday, Nov. 18, to crush the protests. All spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution by the Guards.

For three days, according to these residents, protesters had successfully gained control of most of Mahshahr and its suburbs, blocking the main road to the city and the adjacent industrial petrochemical complex. Iran’s interior minister confirmed that the protesters had gotten control over Mahshahr and its roads in a televised interview last week, but the Iranian government did not respond to specific questions in recent days about the mass killings in the city.

Local security forces and riot police officers had attempted to disperse the crowd and open the roads, but failed, residents said. Several clashes between protesters and security forces erupted between Saturday evening and Monday morning before the Guards were dispatched there.

When the Guards arrived near the entrance to a suburb, Shahrak Chamran, populated by low-income members of Iran’s ethnic Arab minority, they immediately shot without warning at dozens of men blocking the intersection, killing several on the spot, according to the residents interviewed by phone.

The residents said the other protesters scrambled to a nearby marsh, and that one of them, apparently armed with an AK-47, fired back. The Guards immediately encircled the men and responded with machine gun fire, killing as many as 100 people, the residents said.

The Guards piled the dead onto the back of a truck and departed, the residents said, and relatives of the wounded then transported them to Memko Hospital.

One of the residents, a 24-year-old unemployed college graduate in chemistry who had helped organize the protests blocking the roads, said he had been less than a mile away from the mass shooting and that his best friend, also 24, and a 32-year-old cousin were among the dead.

He said they both had been shot in the chest and their bodies were returned to the families five days later, only after they had signed paperwork promising not to hold funerals or memorial services and not to give interviews to media.

The young protest organizer said he, too, was shot in the ribs on Nov. 19, the day after the mass shooting, when the Guards stormed with tanks into his neighborhood, Shahrak Taleghani, among the poorest suburbs of Mahshahr.

He said a gun battle erupted for hours between the Guards and ethnic Arab residents, who traditionally keep guns for hunting at home. Iranian state media and witnesses reported that a senior Guards commander had been killed in a Mahshahr clash. Video on Twitter suggests tanks had been deployed there.

A 32-year-old nurse in Mahshahr reached by the phone said she had tended to the wounded at the hospital and that most had sustained gunshot wounds to the head and chest.

She described chaotic scenes at the hospital, with families rushing to bring in the casualties, including a 21 year old who was to be married but could not be saved. “‘Give me back my son!,’” the nurse quoted his sobbing mother as saying. “‘It’s his wedding in two weeks!’”

The nurse said security forces stationed at the hospital arrested some of the wounded protesters after their conditions had stabilized. She said some relatives, fearing arrest themselves, dropped wounded love ones at the hospital and fled, covering their faces.

On Nov. 25, a week after it happened, the city’s representative in Parliament, Mohamad Golmordai, vented outrage in a blunt moment of searing antigovernment criticism that was broadcast on Iranian state television and captured in photos and videos uploaded to the internet.

“What have you done that the undignified Shah did not do?” Mr. Golmordai screamed from the Parliament floor, as a scuffle broke out between him and other lawmakers, including one who grabbed him by the throat.

The local reporter in Mahshahr said the total number of people killed in three days of unrest in the area had reached 130, including those killed in the marsh.

“This regime has pushed people toward violence,” said Yousef Alsarkhi, 29, a political activist from Khuzestan who migrated to the Netherlands four years ago. “The more they repress, the more aggressive and angry people get.”

Political analysts said the protests appeared to have delivered a severe blow to President Hassan Rouhani, a relative moderate in Iran’s political spectrum, all but guaranteeing that hard-liners would win upcoming parliamentary elections and the presidency in two years.

The tough response to the protests also appeared to signal a hardening rift between Iran’s leaders and sizable segments of the population of 83 million.

“The government’s response was uncompromising, brutal and rapid,” said Henry Rome, an Iran analyst at the Eurasia Group, a political risk consultancy in Washington. Still, he said, the protests also had “demonstrated that many Iranians are not afraid to take to the streets.”

Phroyd

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion | Death by Hanging in Tehran

So Kavous Seyed Emami, an Iranian-Canadian university professor and environmentalist, “commits suicide” in Tehran’s Evin prison two weeks after his arrest. His wife Maryam, summoned last Friday, is shown his body hanging in a cell. He is buried four days later in a village north of the capital, without an independent autopsy and after his family has come under intense Revolutionary Guard pressure to accept the official version of events. Instant Cash Loans

Tell me another. Seyed Emami’s death is an outrage and an embarrassment to the Islamic Republic.

I met him in Iran in 2009, on the eve of a tumultuous presidential election that would lead to massive demonstrations and bloody repression. wishing you very Happy New Year 2020. The theocratic regime that promised freedom in 1979 only to deliver another form of repression stood briefly on a knife-edge. Seyed Emami was a thoughtful, mild-mannered man, a sociologist and patriot with a love of nature. The notion that he would hang himself in a prison where they remove even your shoelaces strikes me as preposterous.

“I still can’t believe this,” his son Ramin Seyed Emami, a musician whose stage name is King Raam, wrote on Instagram.

Since anti-government protests began late last year, mainly in poorer areas that had been strongholds of the regime, Seyed Emami is the third case of a supposed suicide while in custody. In him, several of the phobias of Iranian hard-liners found a focus.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Invisible prisoners of Iran

In 2009, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected to a second term in Iran - it was an unprecedented campaign in the history of this country. For the first time, the candidates held live debates on national television, and the turnout, according to official figures, was an unprecedented 85%. https://medium.com/@com548510/invisible-prisoners-of-iran-df6f678c8032