#3rdcenturyBCE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Carthaginian Army

The armies of Carthage permitted the city to forge the most powerful empire in the western Mediterranean from the 6th to 3rd centuries BCE. Although by tradition a seafaring nation with a powerful navy, Carthage, by necessity, had to employ a land army to further their territorial claims and match their enemies. Adopting the weapons and tactics of the Hellenistic kingdoms, Carthage similarly employed mercenary armies from their allies and subject city-states. Military successes came in Africa, Sicily, Spain, and Italy, where armies were led by such celebrated commanders as Hamilcar Barca and Hannibal. Carthage's military dominance was, though, eventually challenged and bested by the rise of Rome and, following defeat in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), Carthage's days as a regional powerhouse were over.

The Carthaginian Empire

Carthage was founded in the 9th century BCE by settlers from the Phoenician city of Tyre, but within a century the city would go on to found colonies of its own. An empire was created which covered North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and other islands of the Mediterranean. The new territory would be a source of vast wealth and manpower. Conversely, this would also bring Carthage into direct competition not only with local tribes but also contemporary powers, notably the Greek potentates and later Rome. In turn, this created a necessity for large military forces, especially land armies.

Continue reading...

167 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The ancient Greek Theatre. Even on a wet day is stunning!! photo©jadoretotravel #grecoromantheatre #taorminasicily #taorminagreektheatre #ancientgreektheatre #ancientgreektheatreoftaormina #3rdcenturybc #ancientgreeklife #taormina #taorminasicily #discoveringancientsicily #ancientgreece (at Teatro Greco Taormina) https://www.instagram.com/p/B5S1mHXnGWY/?igshid=aa236g67zm75

#grecoromantheatre#taorminasicily#taorminagreektheatre#ancientgreektheatre#ancientgreektheatreoftaormina#3rdcenturybc#ancientgreeklife#taormina#discoveringancientsicily#ancientgreece

0 notes

Photo

📷 Part of the chariot with the helmeted head of a warrior. The head is of a sculptural type characteristic of the work of Lysippos, court sculptor to Alexander The Great. 3rd century BC., Greece?, bronze.(The Immortal Alexander The Great, Hermitage Amsterdam 2010) ▪️ #ancientworld #ancientgreece #chariot #warrior #lysippos #sculptor #bronze #3rdcenturybc #alexanderthegreat #ancienthistory #greece #hermitage #amsterdam #2010 #antiquity #hermitageamsterdam #theimmortalalexanderthegreat

#warrior#lysippos#hermitage#hermitageamsterdam#ancienthistory#antiquity#chariot#ancientworld#bronze#3rdcenturybc#greece#ancientgreece#amsterdam#theimmortalalexanderthegreat#2010#sculptor#alexanderthegreat

85 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Paestum

Paestum, also known by its original Greek name as Poseidonia, was a Greek colony founded on the west coast of Italy, some 80 km south of modern-day Naples. Prospering as a trade centre it was conquered first by the Lucanians and then, with the new Latin name of Paestum, the city became an important Roman colony in the 3rd century BCE. Today it is one of the most visited archaeological sites in the world due to its three excellently preserved large Greek temples.

Founding of the Colony

In the 7th century BCE a second wave of Greek colonization occurred in Magna Graecia and, in c. 600 BCE, colonists from Sybaris in southern Italy founded the colony or city-state (polis) of Poseidonia (meaning sacred to Poseidon) at a spot chosen for its fertile plain, land access through the Lucanian hills, and sea port. According to the ancient historian Strabo, the colonists first built fortifications on the coast before later moving inland to build their city proper. The colony prospered so that by the 6th century BCE there was an important sanctuary (Foce del Sele) and monumental temples dedicated to the Greek goddesses Hera and Athena. The city was planned out in a precise grid pattern and surrounded by walls. The town benefitted from a large agora and became wealthy enough to mint its own coinage and expand its territorial control to the wider countryside. Eventually, Poseidonia administered the plain between the river Sele in the north and the Agropoli promontory to the south.

Continue reading...

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Callimachus of Cyrene

Callimachus of Cyrene (l. c. 310-c. 240 BCE) was a poet and scholar associated with the Library of Alexandria and best known for his Pinakes ("Tablets"), a bibliographic catalog of Greek literature, his poetry, and his literary aesthetic which rejected the epic in favor of shorter works and influenced the later development of Roman literature.

He is considered one of the greatest poets of antiquity, and, through his influence on Roman writers, set the course for Western literary development, especially through his emphasis on brevity and simplicity of form. Among his best-known quotes is "A big book is a big bore," by which he seems to have meant that "less is more" and one should strive to tell one's story as directly and succinctly as possible. Although much has been made of his rejection of Homer, it seems this has been sensationalized. He rejected the standard of literature Homer had come to define but not necessarily the work itself. A similar case could be made for his relationship with the works of Plato, but both authors clearly influenced his own works.

He was never the head of the Library at Alexandria, though this is often claimed, but he may have been the teacher of Apollonius of Rhodes (l. 3rd century BCE), the head librarian after Zenodotus (l. 3rd century BCE) the first librarian at Alexandria. The alleged feud between Callimachus and Apollonius seems to have also been sensationalized and is based on interpretations of fragments of their works as almost nothing is known of the lives of either of them. Apollonius was succeeded as librarian by Eratosthenes (l. c. 276-195 BCE), who may have also been a student of Callimachus.

Although few of his works have survived, he is referenced extensively by later writers who praise his economy of prose and emphasis on an emotional response to personal experience in his poetry. His influence on later writers was enormous, including such notables as Horace, Propertius, Ovid, and Virgil. The details and essential character of his literary aesthetic are still debated today, but not its influence on Western literature.

Family & Early Life

Almost nothing is known of Callimachus' life and most biographical information comes from the Suda (10th century CE), not from his works or those of his contemporaries. He was born to an upper-class family of Cyrene in North Africa and refers to himself as a "son of Battus", meaning Battus I (r. c. 631 to c. 599 BCE), founder of the city of Cyrene and the Battiad Dynasty that developed the surrounding region of Cyrenaica. Callimachus most likely means this reference simply to establish that he is from Cyrene, it does not necessarily mean, as some have claimed, that he was related to the royal house. Scholars Benjamin Acosta-Hughes and Susan A. Stephens give a brief glimpse of his family:

His grandfather, also named Callimachus, was probably the Cyrenean general. Callimachus' sister, Megatima, seems to have married into a high-ranking Cypriot family. A great-grandfather has been identified as Anniceris, a Cyrenean, who, according to an anecdote preserved in Lucian and Aelian, tried to impress Plato by driving his chariot (bound for the Olympic Games) around the periphery of the Academy. Anniceris must have been a man of considerable wealth because he was also said to have ransomed Plato from Dionysius of Syracuse. (4)

Little else is known of Callimachus' early life except that his mother was also named Megatima, he seems to have been educated in Cyrene, and he was living and writing in Alexandria under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (282-246 BCE). Acosta-Hughes and Stephens write:

Callimachus lived the majority of his adulthood during the reign of the second Ptolemy, the period when the Ptolemaic empire was at its height. The Suda tells us that he was an elementary schoolmaster in Eleusis, but if he is already writing for the court in the late 280's BC, his academic career must have been quite brief. In contrast, Tzetzes records that he was a "youth of the court", an official status that is incompatible with elementary school teaching but would fit with a poetic career that seems to have begun in his early twenties. The easiest explanation for the Suda's information is that it was extrapolated from poems in which Callimachus speaks of the schoolroom or schoolmasters. (3)

As a "youth of the court" and later court poet, Callimachus wrote works for Ptolemy I Soter (r. 323-282 BCE), Ptolemy II, and Ptolemy III Euergetes (r. 246-222 BCE). He most likely arrived in Alexandria from Cyrene toward the end of the reign of Ptolemy I. Although it seems he was associated with the Library of Alexandria under Ptolemy II, his position is unclear. He was never the head librarian, and there is no evidence he was involved in acquisitions.

Continue reading...

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Syracusia

The Syracusia was an ancient sailing vessel designed by Archimedes in the 3rd century BCE. She was fabled as being one of the largest ships ever built in antiquity and as having a sumptuous decor of exotic woods and marble along with towers, statues, a gymnasium, a library, and even a temple.

A New Approach

Ancient seafaring is usually perceived as a cabotage maritime navigation. The term comes from the French verb caboter meaning “traveling by the coast.” People of antiquity (Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans) usually sailed following the coastline and did not take the risk of going too far out on the high seas. Nevertheless, there are sources confirming that there were exceptions, and the first of them took place as far back as the 3rd century BCE.

In Sicily, under the ruling of king Hiero II of Syracuse (270 – 215 BCE), a ship with stunning dimensions was built. The material used for the construction of that giant boat equated to the material for 60 regular ships. What was more, that vessel was meant to leave the secure coastal lanes and to cross the Mediterranean Sea. The ship was given a name – Syracusia – and represented what could be called “the first liner of antiquity.”

Continue reading...

110 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ancient Volterra

Volterra (Etruscan name: Velathri, Roman: Volaterrae), located in the northern part of Tuscany, Italy, was an important Etruscan settlement between the 7th and 2nd century BCE. After its destruction by the Romans in the 1st century BCE it became a modest town with the prosperity of its ruling elite into the early imperial period attested by the prodigious number of finely carved alabaster funerary urns in its many rock-cut tombs.

Early Settlement

Settlement on the high sandstone plateau of Volterra began from at least the 10th century BCE. Iron Age peoples of the Villanovan culture, a precursor to the Etruscans, no doubt selected the site for its ease of defence. The site prospered due to the fertile agricultural lands in its territory across the Cecina valley and its rich mineral deposits. Although finds are not as impressive as the coastal Villanovan sites, evidence of a wider trade is found in such foreign imports as Sardinian bronze goods.

Continue reading...

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

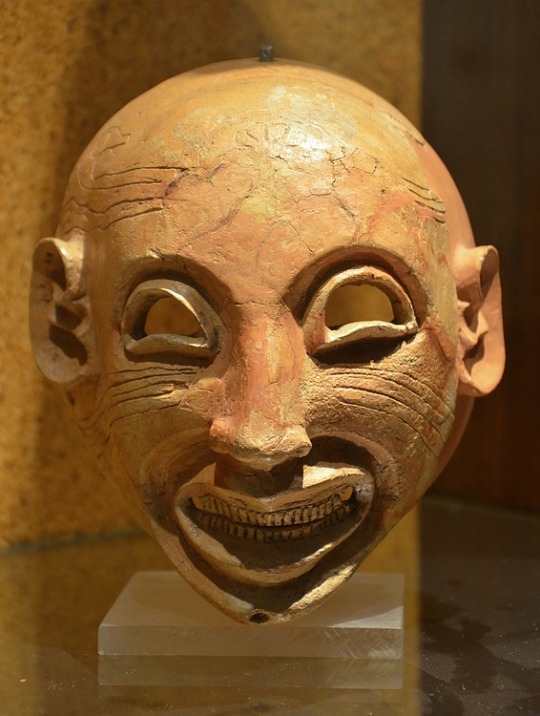

Carthaginian Art

The art of the Carthaginians was an eclectic mix of influences and styles, which included Egyptian motifs, Greek fashion, Phoenician gods, and Etruscan patterns. Precious metals, ivory, glass, terracotta, and stone were transformed into highly decorative objects ranging from everyday utensils to purely ornamental pieces. Just as the Carthaginians imported and exported all manner of trade goods, so too their art reflected their vast network of contacts across the ancient Mediterranean but they would eventually produce their own distinctive art which uniquely blended elements from other cultures. The distinctive qualities of Punic art can be best seen in their stelae, jewellery, sculpture, and masks.

Surviving examples of Carthaginian art are sadly few in comparison to contemporary cultures, and they are further limited in scope by the fact that the majority of artefacts come from a burial context and so are predominantly small in scale and of a religious nature. Secular art and objects produced exclusively for their aesthetic value are rare indeed. Nevertheless, enough examples survive of jewellery, figurines, ceramics, and stonework to hint that the Carthaginians were not as artistically impoverished as earlier historians saw fit to claim.

Influences

Carthage was founded in the 9th century BCE by colonists from the Phoenician city of Tyre. This fact and the city's continued close ties with the mother country meant that art was heavily influenced by that of Phoenicia, at least in its formative years. Just as Phoenicia was itself a melting pot of diverse cultures, its wealth based as it was on maritime trade, so too Carthage would become a cosmopolitan city with visitors, residents, and artists from across the ancient Mediterranean. Egyptian art was particularly influential and many motifs are seen in Carthaginian art such as the goat with head looking backwards beneath a sacred tree or rigid standing female figures. Near Eastern art was another strong influence, seen especially in figurines of the god Melqart/Baal. The influence of Etruscan artists is seen especially in Carthaginian pottery decoration from the 4th century BCE.

Above all, though, Carthage's art took inspiration from the Greek world from the 5th century BCE onwards. Not only were the Carthaginians appreciative collectors of Greek art, taking fine art as booty from their campaigns in Sicily, but they also produced imitative art. There was a large Greek community at Carthage, and many of these must have worked as skilled craftsmen in the workshops of the city. In turn, they would have taught local artists or the next generation. We know of at least one artist whose father was a Greek immigrant but who signed his work as 'Boethus the Carthaginian' and who became so appreciated that his work was dedicated at Olympia.

There is a general problem of identifying the exact origin of many art pieces which is exacerbated by the Punic habit of copying foreign motifs and styles. Traditionally, historians had favoured the view that, at least in general, finer pieces were imported and more rustic art was locally made. This unflattering view is steadily being revised following the discovery of large workshop areas in the city suggesting a healthy export trade and by new archaeological discoveries so that the position that all of the fine art was imported is becoming increasingly untenable.

Continue reading...

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Punic Necropolis of Mahdia

The Punic funerary remains of Mahdia, a series of tombs carved into the rock, date back to a period between the 5th and the 2nd century BCE and are located in the northeast of Tunisia. These tombs are useful for us to understand the acculturation between the local populations known as Libyans and the Phoenicians of eastern origin.

Mahdia

Mahdia is one of the major cities of the ancient Byzacene region and one of the main coastal settlements of the region. The city enjoys exceptional geography and is located on a rock bathed by the sea. This peninsula, about 1.5 kilometres (0.9 mi) long and 400 metres (1300 ft) wide, is attached to the mainland by a narrow sandy strip of land about 170 metres (560 ft) wide.

Mahdia has had many different names throughout its history. It was called Aphrodisium, Alipota, Gummi (the most enduring name), and probably Pharos. Gummi seems to have continued in the Arabised form of Jemma, a place now located in the vicinity. During the Islamic period, the city took its current name of Mahdia. This name is derived from the name of the founder of the Fatimid Dynasty Al-Mahdi (r. 909-934) who settled there and made it the capital of his kingdom from about 920.

The exact location of ancient Mahdia is unknown. The existence of Punic necropolises leads us to believe that there was indeed a Punic settlement corresponding to these necropolises, but we still do not know where exactly. If we examine the relationship between the city of the living and the city of the dead in the Phoenician-Punic world, we could consider locating these necropolises at the periphery of the city. Nothing indicates that the Punic city occupied the same location as the Fatimid city on the Mahdia peninsula; in fact, the name Gummi would correspond to the modern Jemma, which refers to a place outside the walls of the Fatimid city. The Punic tombs, on the other hand, were indeed located on the peninsula.

Continue reading...

26 notes

·

View notes