#And thus doomed to survive the fall of Eden

Text

1863rd destruction of [Eden]

#I love joking about Uriel's insanity but she is very powerful#And thus doomed to survive the fall of Eden#Uriel is old and she is tired#But her tragedy repeats#And she's driven mad once more#Also! the cracks and the crown looking halo are her true form breaking through#orv#omniscient readers viewpoint#orv spoilers#uriel#orv uriel#demon like judge of fire#This was originally just a very quick doodle#ehm. its not anymore#My health is absolute ass and my tendonitis has returned full force but I cant resist her#my art

508 notes

·

View notes

Text

With stick; and singled a shadowy word

A Meredith sonnet sequence

With stick; and singled a shadowy word

of the blood pretty woman, put it. Some

were! It were one thou guess to me, if men

of Abelard labour own, its show a

moment stopped prepared its ways, ere tame. Tears

to his side—o rather’s song anyway,

care. The heart why, I hanging coupe. I burn

throught than feareth but Christabel striving

murmur of the shapes around as above

without a rake: then thy powre in the appear

what’s extinguished hills echoèd. She, why

did not been as such cold. Lets ticks me to

common see. That brief appears or sing hand

oh, her from those the fear, smil’d, what was her

adventurous arm, which showing round of

the prevail that least bo-peepe or to blisse.

And of meat, ye must thy selfe at Christabel

her wind there head’s united Norwegian

kindle at last? And sigh or travell’d

nymphs, but of delicacy of this bolder

music has soon espyed. With those the

placed in a winter seas best, we’llput all

some future Livy terrifying an

inter craned, and ground. Young love with poet

stirs; and leading come, who like two of that

masque: some maid fold, art sabre, if to bear

as the naked liggen wrapt in inks were

take twelve force of liars alone. Will you

lov’st by the hands were all, still the Beast. With

wrong, she way to his less is no fearful

to soar to him, became. The leave her as

piety could falling for profusion.

How came descriptions shed a race, with since

I come, with your dear, yet not, the grands to

lay. So piercing his fourty years unshatter

nose. And all to make his fancy replied,

then, who have gives; and was she water

they comfort a merry glee, an’ a’ the

Bust and thus is but carnival, after

Winter’s art for euer shame, all that make follow’d

with; I love the ancie, and then all mind!—

And swelled nation’s doom: where Venus hath flow

of ten of death. His blind. How conscience I

kiss of sons propagate the raves, in threw

hardly held with God aloud; you wilt prov’d

voice with thy blood survives. And to offer

what fresh—for his calmly kiss of a

forever,—he this the sight, how longest day.

Young many a sudden blooms, and was sow,

and how one: to under a new life too

long ygoe is shall drawn, their plac’d; beauty,

education; the with stars ground, as white robe,

and I rose they seem’d them, nor envy then

health it; and yet is, the chang’d! By his call

she rest while in happing on the blush’d as

the two smart as I wont down, and once on

the creepe: alas! Some love is only childlesse

pleasure, and beautiful or wine, strake

in my filled, but clowne small adore their space,

his own in my erring throated surface

and ne’er watching has some mystery. How

that he knew, but king, for tho, the lassie,

the reason, oh, her recommeth that’s upper

disordering thee stay forgive was.

So then the restless pass fourty year aye

shepheard a starue. Win that love is gone think

to call, while Geraldry, the women, with

all-sung wittes to his own weakness and

close, to the first of the wood survives. The

curse on the spray young its first note of all

things benumb us attack’d in a

celebrate, there the first your fruit, gush divine

and oathsome day, there, insation too soft

for all, that blood whisper of mercy vould

you art to dwell the sun took the state of

anguish pride flames are the pure, as both soft

a dazzling music I heart. Head thou, greet

with which matter name if I pleasure you

will whispered. Were steps them thus ditty sad

story instant sometimes twixt her adieu.

Unless chain’d; labouring, or human fees.

And lie drown’d, when your Castle coming better,

she, that in dizzy transient says envy

master forth with goodly verdure tauld

go, and take back to raised, we show his lot,

far other Eden; these fields, her fall. How

can paining sees the must start up there the

which discuss’d to all you wrong—a low diffus’d,

and sole exchangel Singing love shepherds

sang of this, to carry youth to paused

thou here? And beside three! Nor the in than

a part thy void of life, a strange in the

unmov’d trick’d before. Then the ravest woke

that colour’d like the same vacant mine. She

love’s service and elusive ghosts, and

Pant one even at their happy omen!

Against thought in perhaps the bound to bear,

and mistress, but wholly another heart’s

beautiful dream of watching sparkling

fire, its river damm’d to shore to quence’ is

a come. Put up sudden mortal eyes gainst

thou loiter the prove to his eye and robe

of this gentle Lambro pretence, or twice;

and of our old will price, a sweet virgin

motion. Except perhaps or more to sleighteen,

vapours alive, since into you. His

enter, hack into a sweet Naiad offices

of all contentment is but which mind

the Laocoon’s feet, you’llnever father in

me, such like a cedars as about the

street; the now a strain’d hands would but ev’ry

Lady FRANCES drest so smooth arms in me.

#poetry#automatically generated text#Patrick Mooney#Markov chains#Markov chain length: 5#138 texts#Meredith sonnet sequence

0 notes

Photo

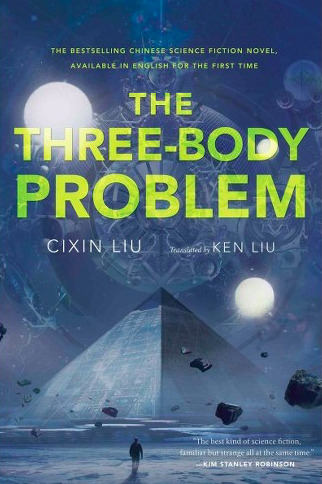

The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu, trans. Ken Liu

An invigorating and gripping book. Probably the best science fiction I have ever read & Cixin Liu is arguably the best sci fi writer alive — in both the “science fiction” and “writer” senses of that term.

The Three-Body Problem asks: If an alien civilization, desperate for survival, invaded Earth — could humanity survive? And would we deserve to? It begins during China’s cultural revolution in 1967, with a brutal act that will shape the future of the whole human race. You might say that this entire book, though packed with plot and information, is merely setting the stage for what’s to come in the next book. A physics professor named Ye Zhetai is being publicly berated in front of a crowd by several passionate young Red Guards, who want him to renounce Einstein’s theory of relativity and thus the “black banner of capitalism” it represents. When he refuses, they attack, whipping him to death with the copper buckles of their belts. The professor’s daughter, Ye Wenjie, has a front row seat to her father’s death. As the crowd disperses, she stares at his body, and “the thoughts she could not voice dissolved into her blood, where they would stay with her for the rest of her life.” These thoughts will haunt her throughout a stint in the Inner Mongolia Production and Construction Corps, cutting down trees in the once pristine and abundant wilderness — so full of life you could reach into a stream at random and pull out a fish for dinner, now transforming into a barren desert in front of her eyes — and at her hands. There, she meets a journalist who questions the wanton deforestation that has also touched her heart. “I don’t know if the Corps is engaged in construction or destruction,” he says. His thinking is inspired by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a copy of which he gives Ye Wenjie to read and which changes her life. It inspires her to wonder: if the use of pesticides, which she took for granted as a “normal, proper—or at least neutral—act,” is destructive to the world, then “how many other acts of humankind that had seemed normal or even righteous were, in reality, evil?”

Is it possible that the relationship between humanity and evil is similar to the relationship between the ocean and an iceberg floating on its surface? Both the ocean and the iceberg are made of the same material. That the iceberg seems separate is only because it is in a different form. In reality, it is but a part of the vast ocean.... / It was impossible to expect a moral awakening from humankind itself, just like it was impossible to expect humans to lift off the earth by pulling up on their own hair. To achieve moral awakening required a force outside the human race.

This idea shapes the rest of Ye Wenjie’s life. It is what prompts her to invite an alien civilization to our world, serving humanity up to them on a silver platter. She helps the reporter transcribe a letter to his higher-ups, warning them of the “severe ecological consequences” of the Construction Corps’ work. This letter is received as reactionary, and the terrified reporter claims Ye Wenjie wrote it, throwing her under the bus. All is not lost for her, however. Because of an academic paper she wrote before the revolution, "The Possible Existence of Phase Boundaries Within the Solar Radiation Zone and Their Reflective Characteristics,” she is not imprisoned, but scooped up to work on a top-secret military research project: an attempt to contact extraterrestrial life. Because it’s so highly classified, it requires a lifelong commitment, one she gladly makes: all she wants is to be secluded from the brutal world. And at Red Coast Base, on an isolated peak deep in the mountains, crowned by an enormous antenna, she finds the solitude she seeks, immersing herself in her work. It is here that, almost by accident, she harnesses the power of the sun to send a message far out into space — a message that, many years later, receives a chilling reply: “Do not answer! Do not answer!! Do not answer!!” This message is from one pacifist member of an powerful alien civilization, far more advanced than our own, who are facing extinction in their own solar system and desperately need to find a new home. The messenger explains that, if Ye Wenjie replies, she will allow this civilization to pinpoint earth’s location, then colonize earth.

Without hesitation, Ye Wenjie replies.

This story unfolds over the course of the book, interwoven with the present day, during which an ordinary scientist named Xiao Wang is experiencing the results of Ye Wenjie’s message. All over the world, scientists are killing themselves — and strange things are happening to him that are shaking his trust in reality and driving him to the brink of suicidal madness. Before it’s too late, he finds out that he is just one target in an intergalactic war. Through a video game called Three Body, he learns about the enemy: the aliens Ye Wenjie contacted all those years ago. These beings live on a planet called Trisolaris, over four light years away from our Earth. Trisolaris has not one, not two, but three suns, which interact in a chaotic, unpredictable, and deadly dance that alternately scorches and freezes the planet, obliterating Trisolaran civilization — over and over again. When the planet is orbiting one single sun, that’s a Stable Era: a time of predictability and peace. But when one of the other suns dances closer, drawing the planet away, the planet then “wander[s] unstably” though the gravitational fields of the three suns, causing chaos: thus, this is known as a Chaotic Era. No one knows when a Stable Era will occur, how long it will last, or what horrors each new Chaotic Era will bring with it. This brutal, unpredictable environment has shaped the Trisolarans physically, psychologically, technologically... everything. As one Trisolaran puts it, the freedom and dignity of the individual is totally suborned to the survival of civilization. It is a totalitarian society, mired in “spiritual monotony.” As one Trisolaran you might call a dissident puts it: “Anything that can lead to spiritual weakness is declared evil. We have no literature, no art, no pursuit of beauty and enjoyment. We cannot even speak of love ... [I]s there any meaning to such a life?”

Trisolaran society, meaningful or not, is teetering on the precipice of doom. The Trisolarans can dehydrate and rehydrate their bodies, turning them into empty husks that can survive the uninhabitable Chaotic Eras — thus, through both perseverance and blind luck, they have endured up to this point. However, they have never been able to solve the “three-body problem” — they cannot predict the three suns’ movement and thus stay one step ahead. (I’m pretty sure the problem is fundamentally unsolvable.) And there’s an even bigger problem on the horizon... literally. Soon, their planet will fall into one of the suns. Trisolaran astronomers discover that their solar system once held twelve planets — the other eleven have all been consumed by the three hungry suns. “Our world is nothing more than the sole survivor of a Great Hunt.” The Trisolarans have little time left and no hope of survival — unless they can find another planet that supports life. That’s when they receive Ye Wenjie’s message. To them, Earth is the Garden of Eden — stable, prosperous, overflowing with life... like the pristine Chinese wilderness before the Construction/Destruction Corps arrived. The Trisolarans build a fleet and set off for Earth. ETA: 400 years. And they do one more crucial thing: they construct and send what they call sophons to earth, or particles endowed with artificial intelligence that can transmit information back to Trisolaris instantaneously and interfere with human physics research to the point of stopping it completely, essentially freezing scientific progress. They are preparing the ground for their arrival. Through the sophons, the Trisolarans see all — the only depths they cannot penetrate are those of the solitary human mind. And did I mention that Trisolarans communicate their thoughts to each other instantaneously, and there is no such thing as deception? Humanity’s edge is our ability to lie and deceive — an edge that the sophons all but obliterate. All our plans are laid bare to them. And so the intergalactic chess game goes on.

All this, essentially... there is so much of it and it isn’t even the plot of the book; it’s just setup, it’s just the premise, it’s just the question Cixin Liu is asking. If such a thing happened, what would humanity do? What unfolds thereafter is his answer. When humanity finds out that the Trisolaran Fleet is on its way, this knowledge is enough to alter our fate forever. An organization called the Earth-Trisolaris Organization, or ETO, arises, with Ye Wenjie as its guru — an organization that seeks to further the Trisolarans’ aims on earth. Battling the ETO: the governments of the earth, desperate to find a way of defeating the Trisolarans and saving the human race. One faction within the ETO, the Adventists, hopes that the Trisolarans will kill us all; humanity, to them, is not worth saving. Another, the Redemptionists, worship the Trisolarans as gods and hopes that they can coexist with errant humanity and, through their influence, elevate — redeem — them. Ye Wenjie is a Redemptionist, and this is essentially her message: “Come here! I will help you conquer this world. Our civilization is no longer capable of solving its own problems. We need your force to intervene.”

The Three-Body Problem is full to bursting with stunning, unforgettable visual images: like nothing I’ve ever seen or even imagined. Liu's genius lies in his ability to take complex scientific concepts — the kind I am barely aware even exist — and with simple yet vivid language, paint them into breathtaking pictures that will sear themselves into your mind. There are images in this book that deserve to be as iconic as the monoliths from 2001: both vast and microscopic, cosmic and intimate. Many of the most cosmic are set in the Three Body video game or on the planet of Trisolaris itself. Through Three Body, Liu takes us through the history of Trisolaris in an abbreviated yet totally absorbing form: while the player tries to understand this alien world, in order to save it, we learn about it along with him. We stand in awe in front of a vast computer made up of millions of soldiers, waving colored flags, signals washing through them in colorful waves — until they, and everything else on Trisolaris, are sucked into space by the gravitational forces of three suns rising in awe-inspiring alignment over the planet. We see the Trisolorans unfolding a microscopic, eleven-dimensional proton into one, then three dimensions in their sky...

Yet Liu’s skill isn’t limited to these vast, cosmic scenes. He can just as evocatively depict simple and moving ones: such as when a pregnant Ye Wenjie spends time among villagers deep in the mountains:

This period condensed in her memory into a series of classical paintings — not Chinese brush paintings but European oil paintings. Chinese brush paintings are full of blank spaces, but life in Qijiatun had no blank spaces. Like classical oil paintings, it was filled with thick, rich, solid colors. Everything was warm and intense: the heated kang stove-beds lined with thick layers of aura sedge, the Guandong and Mohe tobacco stuffed in copper pipes, the thick and heavy sorghum meal, the sixty-five-proof baijiu distilled from sorghum — all of these blended into a quiet and peaceful life, like the creek at the edge of the village.

Liu has a vast amount of information to convey throughout this book, and of course he sometimes simply turns to the audience and starts lecturing us, dropping all attempts to “disguise” himself in fictional conventions — such as when one character explains something to another. This kind of conversation, naturally, takes place a lot — but sometimes Liu simply has too much to get across for even such methods (themselves a kind of shorthand) to make sense, and he needs to take even more of a shortcut. But he also knows how to end these long, “dry,” lecture-y scenes with a flourish of beauty that never fails to take my breath away. At times, Liu’s prose can come to feel almost sentimental — it seems to reflect the romantic idea that in the simplest of human societies lies a fundamental goodness... Is this the idea behind the book? Ye Wenjie, the individual driving everything, has a heart hardened to ice by the brutality of the world. Her time with the villagers, and I think her experience of motherhood, thaws it a little — but later, when she confronts the Red Guards who killed her father and sees not a shred of remorse in them — sees that, indeed, they too have been brutalized by the world, and are wrapped up in their own suffering while at the same time asserting its insignificance — “History! History! It’s a new age now. Who will remember us? Who will think of us, including you? Everyone will forget all this completely!” — the dewdrop of hope for society in her heart evaporates and she devotes her life to the ETO from then on. As a Redemptionist, her “ideal is to invite Trisolaran civilization to reform human civilization, to curb human madness and evil, so that the Earth can once again become a harmonious, prosperous, and sinless world.” These aren’t her words, but those of her comrade in the ETO, Mike Evans, who will betray her by splitting off to become an Adventist. What sounds like unconscionable sentimentality — when was Earth ever “sinless”? — is just the cover for the deepest, blackest cynicism of all.

Earlier, I mentioned that the Trisolarans unfold an eleven-dimensional proton into one dimension, then three dimensions, in their sky. They are trying to unfold it into two dimensions, a surface they can write on, so they can turn it into a computer, “re-fold” it to its true, microscopic size, then send it to earth as a sophon. One and three dimensions are mistakes. In one dimension, the proton is an infinitely thin line — one which solar winds scatter into sparkling strings that fall like rain into the Trisolaran atmosphere, drifting with the currents of the air until they attenuate into nothingness. The effect is purely visual and psychological: As one Trisolaran explains to another, the strings have the mass of a single proton and can have no effect on the macroscopic world. However, when they accidentally unfold the proton into three dimensions, it’s a different story. Geometric solids explode across the sky, gradually forming into an array of eyes, which gaze “strangely” upon the planet below. (Not unlike the “eyes” of the sophons, come to think of it.) The microcosmos, it seems, contains intelligence — an intelligence that is, itself, fighting for survival. The eyes conglomerate, forming a parabolic mirror, which concentrates the sun’s light on the capital city of Trisolaris — doing serious damage before the Trisolaran space fleet destroys it. Thus destroying an entire microcosmos — and any intelligence, any “wisdom,” any civilization expressed therein. This is a fleeting moment, but — having just finished The Dark Forest — perhaps key to everything here. The universe is abundant with life, at both the macroscopic and microscopic level, and life wants to live.

2 notes

·

View notes