#Austrian Napoleonic Cavalry

Text

Sergeants Czapka of Uhlan Regiment No. 1 from the Austrian Empire dated to 1806 on display at the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum in Vienna, Austria

Uhlans were light cavalry units that primarily used a lance in battle and the Austrian Empire primarily recruited these soldiers from the Polish lands within the empire. They wore square topped hats called Czapka's which became popular all over Europe during the 19th century.

During the Napoleonic Wars when Napoleon's army crossed the danube the Regiment No. 1 harassed the French army using hit and run tactics rather than meeting them in battle.

Photographs taken by myself 2022

#uniform#cavalry#napoleonic wars#austria#austrian#austrian empire#19th century#fashion#hapsburgs#heeresgeschichtliches museum#vienna#barbucomedie

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colonel Auguste de Colbert-Chabanais, of the 10th Regiment of Chasseurs à Cheval, at the Battle of Elchingen, 14 October 1805

by Alphonse Lalauze

#battle of elchingen#art#alphonse lalauze#france#austria#french#austrian#napoleonic wars#napoleonic#history#europe#european#cavalry#prisoners#auguste de colbert chabanais

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleonic era French light cavalry officers' sabre with the à la Marengo style hilt

This style of sabre hilt, with the rounded langets and semi-S shaped guard. Is one of two types that are associated with the la Marengo type. The other has a similar cross guard but a pommel cap that bends towards the knuckle bow, decorated with a lions' face.

These styles are said to have gained popularity following Consular Napoleon's victory over the Austrians in Jun 1800 at the Battle of Marengo. French sword cutlers purportedly drew their inspiration from the sabre carried by Napoleon during the campaign.

It has been claimed that only officers who had participated in the battle were permitted to carry this style of hilt, however this is unlikely to have been true, given the number of surviving examples.

This sword carries a Solingen made 'export' blade with generic engraving that would originally have been highlighted in gold on a background of blue.

Stats:

Overall Length - 935 mm

Blade Length - 795 mm

Curve - 54 mm

Point of Balance - 140 mm

Grip Length - 125 mm

Inside Grip Length - 105 mm

Weight - 700 grams

#swords#sabre#Napoleonic era#military antiques#antiques#sabres#cavalry swords#military#19th Century#Light cavalry#French military

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was going back through some of your posts about economically improving the various Seven Kingdoms, and you mentioned setting up a military academy in the North and that got me thinking-when did military academies start being a thing in Europe, and were there any examples from a time and place like Westeros, where most combat is fought with melee weapons rather than gunpowder?

Great question!

The first military academy was established by the House of Savoy in Turin in 1678, placing it pretty firmly in the early modern period. So it does fit within the loose boundary I had established for my economic development project.

However, they didn't really become widespread until the middle of the 18th century, as Denmark, Norway, Britain, and especially France established military academies - with the French École Royale Militaire becoming the model for the Prussians, Austrians, and Russians.

Regarding the technology, military academies occupy an interesting place in the early modern military revolution. When the Savoyard academy was first established, Europe was very much in the pike-and-shot period of military history, where you still have a lot of pikemen on the battlefield backing up the musketeers.

However, in the period from 1700-1750 when the military academy really took off, pike formations had disappeared from professional European militaries due to the introduction of the bayonet. Now, this didn't mean that melee weapons disappeared from the battlefield - while dedicated melee combatants were now restricted to the cavalry, throughout the Napoleonic period, it was the bayonet and not the cannon or the musket that was the dominant player on European battlefields.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Marengo was fought on 14th June, 1800 between French forces under the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte and Austrian forces near the city of Alessandria, in Piedmont, Italy.

Surprised by the Austrian advance toward Genoa in mid-April 1800, Bonaparte hastily led his army over the Alps in mid-May and reached Milan on 2nd June. After cutting Melas's line of communications by crossing the River Po and defeating Feldmarschallleutnant (FML) Peter Karl Ott von Bátorkéz at Montebello on 9th June, the French closed in on the Austrian Army, which had massed in Alessandria. Deceived by a local double agent, Bonaparte dispatched large forces to the north and the south, but the Austrians launched a surprise attack on 14th June against the main French army, under General Louis Alexandre Berthier.

Initially, their two assaults across the Fontanone stream near Marengo village were repelled, and General Jean Lannes reinforced the French right. Bonaparte realized the true position and issued orders at 11:00 am to recall the detachment under Général de Division (GdD) Louis Desaix while he moved his reserve forward. On the Austrian left, Ott's column had taken Castel Ceriolo, and its advance guard moved south to attack Lannescs flank. Melas renewed the main assault, and the Austrians broke the central French position. By 2:30 pm, the French were withdrawing, and Austrian dragoons seized the Marengo farm.

Bonaparte had by then arrived with the reserve, but Berthier's troops began to fall back on the main vine belts. Knowing that Desaix was approaching, Bonaparte was anxious about a column of Ott's soldiers marching from the north and so he deployed his Consular Guard infantry to delay it. The French then withdrew steadily eastward toward San Giuliano Vecchio as the Austrians formed a column to follow them, as Ott also advanced in the northern sector.

Desaix's arrival at around 5:30 pm stabilized the French position, as the 9th Light Infantry Regiment delayed the Austrian advance down the main road and the rest of the army reformed north of Cascina Grossa. As the pursuing Austrian troops arrived, a mix of musketry and artillery fire concealed the surprise attack of Général de Brigade (GdB) François Étienne de Kellermann’s cavalry, which threw the Austrian pursuit into disordered flight back into Alessandria, with about 14,000 killed, wounded or captured.

The French casualties were considerably fewer but included Desaix. The whole French line chased after the Austrians to seal une victoire politique (a political victory) that secured Bonaparte's grip on power after the coup.

It would be followed by a propaganda campaign that sought to rewrite the story of the battle three times during his rule.

(Information From Wikipedia)

Painting - THE BATTLE OF MARENGO

Artist(s) : LEJEUNE Louis François (baron)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

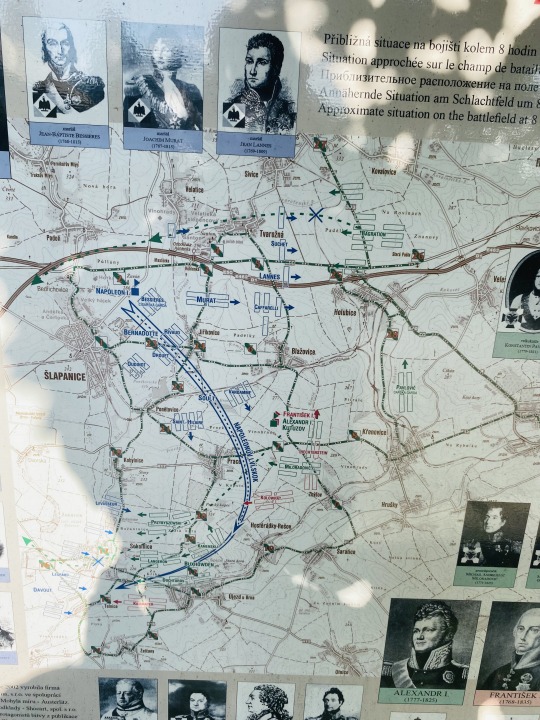

My Trip to Austerlitz (pt. 1)

The sequel to last week’s My Trip to Koniggratz! expect pictures of museums, fields, and heavy MilHist nerdery.

The battle of Austerlitz was fought near Slavkov in what is now the Czech Republic on 2 December 1805 between Napoleon’s French Grande Armée (c. 70,000 strong) and the allied forces of Russia and Austria (c. 90,000). It is generally considered Napoleon’s greatest victory.

The battlefield is big, stretching over thirteen kilometres and incorporating half-a-dozen villages. The main feature is a low ridgeline known as the Pratzen Heights, and the village of Pratzen itself, which sits at its base. There’s a museum on the heights dedicated to the battle.

Needless to say, it has the obligatory uniforms.

And the obligatory cannon. The battle is sometimes known as the battle of the three emperors after Napeoleon, the Russian Tsar Alexander, and the Austiran emperor, Francis II.

Outside is the Cairn of Peace, built in the early 20th century.

Napoleon’s army, outnumbered, had been withdrawing before the Russo-Austrian advance throughout late November 1805. Hoping to lure his enemies into a decisive battle, he deliberately abandoned a strong position on the Pratzen Heights, hoping to lure the Allies into taking it. They duly did.

Napoleon adopted a defensive stance along a stream known as the Goldbach. He deliberately weakened his right flank at the villages of Tilnitz and Sokolnitz, hoping the Allies would try and attack him there while knowing he had reinforcements marching from Vienna bound for that location.

While the Allies were lured off the heights they had first been lured onto, Napoleon would then strike at their weakened centre, taking the ridgeline.

The battle began early on 2 December with an Allied assault on the village of Tilnitz. This quickly spread to neighbouring Sokolnitz. Both locations were the scene of ferocious fighting throughout the day as they were taken and then retaken, possibly as many as five times.

These are barns in Sokolnitz that were using as strong points by both sides, and later as makeshift prisons for captured Russians.

Sokolnitz castle, another centre of the fighting in this southern sector of the battlefield. It’s now an old people’s home.

By mid-morning 3 of the 4 main Allied columns had moved down off Pratzen Heights to attack Tilnitz and Sokolnitz. The 4th was still on the heights however, as it had been disrupted by Allied cavalry who moved through it heading for the north of the battlefield.

General Kutuzov, a veteran Russian commander, didn’t want to leave Pratzen largely undefended, but the Russian Tsar, Alexander, ordered him down. Before he could, however, Napoleon struck.

This is the view from the highest point of the Pratzen heights looking out over Pratzen village towards the French centre. On the day of the battle there was a heavy fog, so it was impossible to see French forces massing for the masterstroke here.

The French advanced and, after overcoming their shock, the Allies scrambled forces to intercept and stop them seizing the ridgeline. Heavy fighting flared in Pratzen village itself, and along the slopes.

This is the view from the opposite side. Napoleon spent the morning on Zuran hill. Here we see what Napoleon would have looking towards the Allied centre on Pratzen Heights.

While all this was happening, fighting also flared in the northern sector of the battlefield, around the villages of Holubitz and Bosenitz. A ferocious cavalry engagement developed in these fields.

The deaths of an estimated 7,000 horses are commemorated here, on ground that now holds a functioning stable.

Both sides fought hard, but the French proved more adept at small-scale tactics, with proper support between infantry and cavalry, while the Allied cavalry tended to fight unsupported.

(There’s going to need to be a part 2 as I can only upload so many images to one post, thanks tumblr)

#austerlitz#battle of austerlitz#history#military history#napoleonic#napoleonic wars#19th century#napoleon

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

O wae is me my hert is sair, tho but a horse am I.

My Scottish pride is wounded and among the dust maun lie.

I used to be a braw Scots grey but now I'm khaki clad.

My auld grey coat has disappeared, the thocht o't makes me sad.

- Royal Scots Greys, poem recited in reaction to the change their scarlet uniforms and grey horses to khaki.

Formed in 1681, the Royal Scots Greys cavalry unit was Scotland's senior regiment. Its long and distinguished service continued until 1971, when it was merged into The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

The regiment was formed as The Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons in 1681 from a number of existing troops of cavalry. Its first action was the suppression of the Earl of Argyll’s rising, launched in 1685 in support of the Duke of Monmouth’s revolt.

Following the Glorious Revolution (1688), the regiment went over to King William III, fighting for him against the Jacobites in Scotland. It was ranked as the 4th Dragoons in 1692.

The following year, the entire regiment attended a royal inspection in London mounted on ‘greys’ (horses with white or dappled-white hair). This gained it the nickname ‘Scots Grey Dragoons’. However, this only became part of its official title in 1877, when it was renamed the 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys).

After a period of home service, it joined the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14). The regiment fought at Schellenberg (1704), Blenheim (1704), the Passage of the Lines of Brabant (1705), Ramillies (1706), Oudenarde (1708), Tournai (1709), Malplaquet (1709) and Bouchain (1711).

It spent a further period on home service until 1742, when it joined the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). The regiment deployed to Germany first, fighting at Dettingen (1743). It then moved to Flanders, where it served at Fontenoy (1745), Rocoux (1746) and Lauffeld (1747).

It’s next major battle honour was at the Battle of Waterloo (1815). This was its only Napoleonic battle honour, at which 201 of its men and 228 of its horses were killed attacking a French infantry brigade. In this attack, Sergeant Charles Ewart captured the French 45th Line Infantry Regiment’s eagle. This later became part of the unit’s cap badge.

A long period of home service followed until the Crimean War (1854-56). There, the regiment won two Victoria Crosses charging uphill against 3,000 Russian cavalry at Balaklava (1854).

On returning home, it saw no further active service until the Boer War (1899-1902) in 1899. During this campaign, it camouflaged its white horses with khaki dye. In the years since Balaclava, much had changed about warfare. Gone were the red coats and bearskin shakos. The Scots Greys would now fight wearing khaki. In fact, with the popularity of wearing khaki that accompanied the start of the Boer War, the Scots Greys went so far as to dye their grey mounts khaki to help them blend in with the veldt. It took part in the Relief of Kimberley, fighting at Paardeberg (1900), before joining the advance to Bloemfontein and later Pretoria, service that included the Battle of Diamond Hill (1900). It also fought in the anti-guerrilla campaign in 1901-02.

After returning home in 1905, the Scots Greys stayed in Britain until August 1914, when it moved to France.

It fought on the Western Front as both cavalry and infantry, winning several battle honours including the Retreat from Mons (1914), Marne (1914), Ypres (1914), Neuve Chappelle (1915), Arras (1917) and Amiens (1918).

According to a report in Scottish newspapers of the time it was decided to paint the horses khaki as their grey coats were too visible to German gunners. This gave rise to a comic poem posted above, of which this is the first verse.

**Royal Scots Dragoon Guards set off from Edinburgh Castle

#royal scots greys#royal scots dragoon guards#regiment#british army#scotland#soldier#horses#horse riding#edinburgh castle#military#traditions#military traditions

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

As an addition to my posts on sword grips, here is a size comparison between the heavy and light cavalry trooper swords of the French and British Napoleonic armies.

From top to bottom:

French Model An XIII Sabre of the line, - used by Dragoons and Cuirassiers

Originally this blade would have been issued with a hatchet point making it slightly longer. However, by 1814 field modifying them into spear points became common and in 1816 this became an official modification, getting retroactively applied to swords in service.

Total Length: 1120mm

Blade Length: 960mm

Sword Weight: 1300 grams

British 1796 Pattern Heavy Cavalry Sword

Based on the Austrian model 1769 the British sword was originally issued with a hatchet tip. However, like their French opponents, field modification into a spear point became common practice to make the sword more effective in the thrust.

Total Length: 1020mm

Blade Length: 890mm

Sword Weight: 1020 grams

French model An XI, - used by ‘Hunters on horse’, Hussars, Lancers, and Mounted Artillery

Introduced in year eleven (1802) of the Revolutionary calendar the AN XI came about as a rationalisation of the different models of light cavalry sabres in service to meet the supply demands of near constant warfare the new French state found itself in.

Total Length: 1010mm

Blade Length: 870mm

Sword Weight: 1190 grams

British 1796 Pattern Light Cavalry Sabre, - used by Light Dragoons and Mounted Artillery

Designed by John Gaspard le Merchant with cooperation from Henry Osborn in response to complaints of British cavalry troopers on the poor performance of their 1788 pattern sabres. Based loosely on Eastern European sabres the 1796 LC proved to be a hard hitting sword and immensely popular.

Total Length: 945mm

Blade Length: 820mm

Sword Weight: 880 grams

#sword#swords#sabre#1796 Pattern#An XIII#An XI#Light Cavalry#Heavy Cavalry#Antiques#British Army#French Army#Napoleonic Wars#Cavalry

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 4: Army life for the Napoleonic infantryman morphing into...

... the battle of Ulm.

This is my fourth and last translated post drawn from an article in the September 2019 issue of Historia magazine, This the same magazine from which I posted eight biographical sketches of Marshals recently. I was inspired to do this by @history-and-arts‘s recent participation in a re-enactment of the battle of Waterloo.

The article is specific to the battle of Ulm, but parts of it described aspects of army life applicable throughout the Napoleonic era.

For the two years preceding this battle, Napoleon had been involved in preparing an invasion of Britain, and had stationed seven army corps along the northern coasts of France and the Flemish coast, Bernadotte holding the easternmost position in Holland, and Augereau the westernmost at Brest. This final post will concern the seven army corps marching to Ulm, and some information regarding the battle itself.

One bit of preliminary information: when historians refer to Boulogne, they don’t mean just the city of Boulogne itself, but the entire seven army corps along the coast facing England. The distance between these corps’ encampments and Boulogne itself, where Napoleon had his headquarters, could be hundreds of kilometres.

The Magnificent Seven (no, not the movie)

Each corps, commanded by a marshal and comprising the different branches of the army - namely the infantry, the cavalry, artillery, and engineers -, followed a separate route in order to speed up movement and facilitate provisioning of supplies. The marches were organized by divisions, each spaced one day apart. Despite these precautions, the marching columns spread over long distances.

From Boulogne to Ulm

August 1805: Napoleon was planning to land in England when Austria's declaration of war caught him by surprise. A third coalition, including Russia, had arisen against him. Without delay, he had to turn his army around and rush to Germany. In order to prevent his enemies from joining forces and outnumbering him, he had to crush the Austrians. The Grande Armee departed from Boulogne on 29 August 1805 and moved in what Napoleon called "seven torrents", covering almost 40 km per day and reaching the Rhine on 25 September. Less than a fortnight later, on 7 October, it crossed the Danube. As a result of the speed of its progress, Napoleon's army trapped the Austrians inside the stronghold of Ulm and forced them to capitulate on 17 October.

This last part of the article is accompanied by a map showing the position of the army corps on September 25, as well as their individual paths to Ulm. In a rough north-north-east line, starting from the south and going north, we have Murat, Lannes, Ney, Soult, Davout, Marmont, and Bernadotte. The seventh “magnificent”, Augereau, is missing. Murat’s path is shown as an assemblage of curlicued arrows, as he was ordered by Napoleon to feign an attack so as to distract the Austrians. To the north, Marmont and Bernadotte seem to have crossed paths at some point, Marmont’s corps taking the northernmost position.

My copy of David G. Chandler’s The Illustrated Napoleon has a similar map on page 44. It includes some differences and additional information. Murat’s movements are shown with similar curlicues, but Marmont’s and Bernadotte’s armies apparently merged in Wurzburg, about 80 miles from Ulm. Augereau’s corps is at least 100 miles away, not surprising since it had the longest distance to travel. Wrede and Deroi are shown fighting with the French at the head of Bavarian troops. I know that Deroi died in batttle, but I’m not sure if it happened at Ulm. Be it as it may, there is a painting showing Deroi being carried off a field of battle.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint-Cyr: A Bad Comrade? Part 2: Context

Last we left off, we covered a potential action of Saint-Cyr’s that could have led to his reputation as a bad comrade. In his 1856 biography of Saint-Cyr, Gay de Vernon gives us the context that Saint-Cyr’s negative reputation came to be through an unfavourable light that Moreau and his circle cast on Saint-Cyr due to his behaviour.

Although Saint-Cyr frequently argued against or forwent Moreau’s orders, Gay de Vernon illustrates the cumulative frustration Saint-Cyr had experienced as Moreau’s premier lieutenant which might have induced him to do so. As premier lieutenant, he was officially authorised to command over all the other generals of division, and commanded the center of Moreau’s Armée du Rhin (p. 170-171, footnotes). It would make sense to me that Saint-Cyr had some degree of authority to question Moreau's orders.

As soon as he first met up with Moreau, Saint-Cyr had quickly taken to critiquing Moreau's special commandment of the reserve; he pressed Moreau to change an unsound, complicated and grossly inconvenient organisation. …

Saint-Cyr had put much insistence in his observations, and expressed his design of resigning if Moreau did not revert to the correct principles of organisation. Moreau, who knowingly deceived him, only responded feebly, with embarrassment, and persisted in his unfortunate resolution; but he managed to persuade Saint-Cyr to at least start the campaign, and Saint-Cyr always reproached himself for this moment of condescension.

The pretensions of the adjutant-général Lahorie and his grave influence on Moreau had committed him to adopting and maintaining this formation of the army.

… On 25 April, the army passed the Rhine; …. During this long journey, Moreau did not leave Saint-Cyr, and the latter remarked, not without bitterness, that the general in chief did not accord him as much confidence as before; he resolved thus not to make any observations from now on, and to content himself with executing, [as quoted from Saint-Cyr’s memoirs of the 1800 campaign,] "as much as is possible in war, the orders he received. Having taken this determination, he did not deviate from it the whole time he remained in the army.” (p. 150)

Although Saint-Cyr's statement somewhat contradicts his later actions, Gay de Vernon’s point is that Saint-Cyr refused to be corrupted by cronyism, and even under what he perceived as a disservice to the army, to follow the orders of his superior officer as far as possible. However, Gay de Vernon's view may also have been tainted by the Napoleonic bias against Lahorie (also spelled La Horie), who seems to have never existed comfortably in Napoleon’s France, for he was implicated in Pichegru's and Moreau's conspiracies and was forced to go into hiding, helped by Victor Hugo's parents (interestingly, Hugo was his godson). He was later executed in 1812, allegedly for conspiring against Napoleon in accomplice with Malet.

In addition to proving Saint-Cyr’s incorruptibility, Gay de Vernon also gives explicit counterexamples to Saint-Cyr’s reputation as a bad comrade.

On 16 May, Kray, profiting skillfully from the occassion offered to him to batter [divisional commander] Sainte-Suzanne, isolated on the left of the Danube, attacked him in person with a corps of 30,000 men, of which 9,000 were cavalry.

[The next part is quoted from Thiers' Histoire de la Révolution Française:] "Fortunately Saint-Cyr came running in haste,… Hearing the cannonade on the left bank, he had sent aides de camp after aides de camp for bringing back the divisions on edge of the Iller to the edge of the Danube. ... The combat of canon-fire [which Saint-Cyr arranged] gave the Austrians inspiration for their retreat, brought them back, relieved Sainte-Suzanne, and spread in the ranks of [the unfortunate French soldiers] a most lively joy, a completely new ardour." (pp. 163-164)

In light of the above two examples, Saint-Cyr did not seem to have acted out of spite for his comrades or to gain glory for himself, but because he was a genuine stickler for regulations and discipline and a believer of efficiency in battle over mindless obedience to a superior command, at least up until the campaign of 1800. Even then, he could make concessions and work for the 'greater good’ the army until its organisation became intolerable for him.

Saint-Cyr's concern for executing "the art of war" perfectly would lead him to clash with Moreau for a final time due to the latter’s confusing leadership. In particular, Moreau decided to cross the Danube on 19 May to face Kray on the other coast of the river.

The troops, full of ardour and confidence, waited to mount the assault the next day, and Saint-Cyr pressed the general in chief to carry out this vigorous decision. Moreau could not bring himself to do so, and brought the army back to the right of the Danube, where it demurred twenty days in a sort of inaction.

Such continuous fumbling, which, after the three victories of Engen, Mösskirch and Biberach, had reduced to powerlessness the best and most numerous of [the French] armies, disgusted Saint-Cyr more and more; he complained openly of these hesitations, of these uncertainties, of the multitude of unmotivated orders and counterorders which diminished the confidence of the the troops and raised the morale of the enemy… when Saint-Cyr had acquired proof that [Moreau] was in no way thinking to modify the organisation of the army, he demanded to resign, on 6 June, and he separated forever from Moreau; they parted almost hurriedly. (P. 164-165)

All in all, Saint-Cyr seemed to be quite a perfectionist: if events did not go according to plan, and no one was listening to his critique and solutions, he was likely to wash his hands of it. To put it more colloquially, his attitude was not malicious and felt more like, "I’m surrounded by idiots. Since they aren’t listening to my advice, I give up on them."

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Officers Shako of the Hussar Regiment No. 5 of the Austrian Empire dated to 1814 on display at the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum in Vienna, Austria

Officers shakos often had a feather to identify them on the battlefield as commanders. Unfortunately that made them more of a taget for the enemy, in this case artillery which destroyed this shako and presumably the offcer wearing it.

In 1814 the Hussar Regiment No. 5 was fighting in Northern Italy and taking part in the sieges of Venice and Mantua where perhaps this officer was struck by the defenders cannon fire.

Photographs taken by myself 2022

#cavalry#uniform#fashion#19th century#napoleonic wars#austria#austrian#austrian empire#military history#hapsburgs#heeresgeschichtliches museum#vienna#barbucomedie

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The French in Passau 1805/6

The formerly independent town of Passau had only been integrated into Bavaria during the secularisation, in 1803. In autumn of 1805, the town saw quite some movement: First the Austrians invaded and occupied the town (because that idiot elector Max Joseph had made an alliance with the French and all that), then all of a sudden the Austrians hastily retreated, and the French came… (Translated from A. Erhard, Geschichte der Stadt Passau (History of Passau), Volume 1, Passau 1862):

On the 1st of November, the French war commissioner Dourgiout arrived in Passau and demanded from the magistrate for the fifth army corps under General Oudinot the following delivery: 100,000 bread rations - 100 oxen - 6000 pints of brandy - 2000 pairs of shoes - [..., lots of more stuff ...] All these items were to be brought as early as 6 o'clock the following morning [...].

But that’s when we have our morning coffee!

Oudinot is in a hurry and can’t wait for those ponderous Bavarians anyway, he just grabs whatever clothes they have managed to pile up and moves on. Next is the division of general Dupont, quartered in the city and causing such a ruckus, that the town’s new military commandant, Barrère, has to issue an order of the day reminding the soldiers that those guys they are currently staying with are allies, not enemies. So be on your best behaviour, if you please!

Dupont’s division moves on except for a garrison of 800 men under Barrère. On 14 November, the city coffers are already empty. And there are still a full two weeks to go until even Austerlitz!

By letter of 27 November to the members of the municipal council, Commander Barrère indicated that he was in financial difficulties and needed an advance. He was sent 50 ducats by a member of the magistrate's office, and 25 ducats to his secretary, with the expression of regret that due to the poor state of public coffers, no larger sum could be provided. Nevertheless, he was respected and popular in Passau because of his willingness to serve and his condescension towards the citizens, and his dismissal at the end of November was heard with general regret.

In the month of December, the headquarters were transferred to Passau under General Verdiere [sic! Verdier?], who appointed his adjutant Mutelé [no clue what name they butchered here] as commander of the town and fortress. This selfish and brutal man demanded a riding horse worth 330 guilders and a precious saddle blanket worth 103 guilders immediately after his arrival, and he received them. His adjutant and secretary also demanded and received gifts in cash. [...]

General Verdiere was a strict and ruthless man who knew neither measure nor aim in his demands on the city, but knew how to clothe them in a pleasing garment. [...]

On 28 December, city commander Mutelé informed the magistrate that the arrival of Emperor Napoleon in Passau was to be expected by the hour [...] On the same day in the evening, Napoleon, returning from Austria, arrived in Passau with Berthier, Duroc and Androissy [sic!] [...] The Emperor stayed only briefly, had some eggs and left again at ten o'clock in the evening. The city had to pay a bill of 175 guilders for catering to his entourage. [...]

380 to 390 Francs, by my makeshift conversion rate.

As more and more troops on the march pass through town and cause unbearable costs, two deputies are sent off to headquarters in order to ask for the troops to be sent on to another road. But no such luck.

On the contrary, the French showed no desire at all to leave Passau, but rather seemed intent on making themselves at home here for a long time to come. However, General Lefebre, who had taken command of the city and fortress at the beginning of February, at least transferred the cavalry to the surrounding countryside at the urgent request of the citizens to relieve the city. In return, however, he demanded a gift of two fine chariot horses, which was granted.

Then there’s a typhus epidemy killing soldiers, doctors and civilians, and as there’s hardly any money left to support the hospitals, Lefebre threatens to quarter the sick with the town folks in their houses - presumably so the disease could spread faster... And as if all that were not enough, now this:

On 6 March, Marshal Soult arrived in Passau from Braunau with three six-horse carriages and his entire general staff and chose the Residenz building as his quarters.

Bugger. THE greatest plunderer of them all (well, minus Masséna. Maybe.) Plus, he’s about to stay for almost five long months…

From now on, better days came for the unfortunate inhabitants of Passau. Marshal Soult, under whom Generals Lefebre and Legrand commanded, distinguished himself from all his predecessors by a friendly and humane demeanour, maintained strict discipline and thus made himself very popular with the inhabitants (411).

What? 👀👀👀 No way! Can’t be! Must be some other Marshal Soult! Probably his non-evil twin bro… oh, wait, let me translate that footnote…

(411) He nevertheless took the most beautiful paintings from the former prince-bishop's residence with him on his departure.

Oh. Okay. Guess it was the real Soult then. 😁

#napoleon's marshals#jean-de-dieu soult#Third Coalition War#bavaria1805#everybody needs a signature move#and a hobby#like nicking paintings

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

1796 Heavy cavalry troopers sword by Dawes in original configuration (although the grip leather has been replaced).

When Major John Gaspard Le Marchant, proposed his new cavalry sabre design with his system of mounted swordsmanship; his intention was for his new sabre to be the universal sabre for the British cavalry (a concept that was 60 years ahead of it's time).

And while his sword was accepted as the 1796 Pattern light cavalry sabre, the officers of the heavy cavalry insisted on a straight bladed design. Falling back on his experiences with the Austrian cavalry in the Low Countries campaign (1793-95) he suggested a sword that was an almost direct copy of their model 1769 pallasch.

While an effective cutting sword, the hatchet tip of the 1796 HC, was not suitable for thrusting and in service these were often re-profiled to have a spear tip. Other changes included removing the langets and narrowing the guard on the inside to prevent wear on the uniform while wearing.

Like it's light cavalry counterpart, the 1796 Pattern sword was also exported to Britain's allies; Portugal and Sweden during the Napoleonic wars.

#sword#back-sword#pallasch#1796 Pattern#1796 pattern heavy cavalry sword#cavalry#British Army#Georgian Era#Napoleonic wars#military antiques#heavy cavalry#John Gasapard Le Marchant

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many things were said, many things were seen - at last we’re approaching the finish line! 🎉

So here comes

Part 3 of the main characters in the Kraft’s painting “Battle of Leipzig”

After all the trouble with an escort of three allied monarchs we have a suitable opportunity for a closing speech - a speech about prominent Austrian military men who participated in the Battle of Leipzig and got their moment of fame on the Kraft’s canvas.

Naturally they are led by their general-commander who presided over allied Russian, Prussian, Austrian and German forces - prince Karl Philipp zu Schwarzenberg, Austrian field marshal and experienced diplomat.

Representative of an ancient, well respected family in Habsburg’s monarchy (Franconian/Bavarian heritage with a pinch of Czech influence, money and - notably - property), he was one of the closest and most loyal Metternich’s associates whose gentleness, pliability and diplomatic skills combined with his influence in the army and utter bravery always came in handy when Klemens wanted to accomplish something on an international arena ever since he became chancellor in 1809.

Same thing goes for the war of 1813-1814: since newly formed Coalition needed a commander, probably an Austrian one as Russians and Prussians needed to ensure Austrian involvement in the business against Napoleon, Metternich simply swept other candidates aside (especially archduke Karl von Teschen who probably was the most successful military commander in the Empire… but indescribable boiling h a t r e d between the imperial family and chancellor lurking behind the back of emperor Franz and gracefully pulling the strings was practically insurmountable) and put in an ally he trusted the most.

Like, you know, find yourself a man who can do both! Because Klemens surely found one for himself. ✒️🗡

(This saying actually suits them soooo well, it’s unbelievable. Sometimes I still can’t comprehend how much of “partners in crime” they were (love their dynamic as much as Metternich’s relationships with Friedrich von Gentz) and I will certainly mention them A LOT in the nearest future!)

But for now that’s more than enough chatter about the commander-in-chief, I guess…

Especially when there is such a wonderful pair of true sweethearts behind his back - Hieronymus von Colloredo-Mansfeld and Friedrich VI von Hessen-Homburg, a field marshal and general of the cavalry in the Austrian service! Both went through the Napoleonic wars from it’s start to the very end. Also they properly illustrate the famous notion of “internationalism” which was common amongst the ranks of Austrian Empire’s officials thanks to the legacy of Holy Roman Empire (R.I.P as Napoleon said it himself… ☠️): Colloredo came from a noble family from Friuli (Northern Italy) and Friedrich’s name says it all for him. :)

Even though they seem completely fine on the canvas, both were severely wounded during a fierce confrontation with the troops of Poniatowski, Augerau and Oudinot which took place on the 18th of October. Friedrich who led his hussars in a battle suffered a serious blow…

Fortunately, Colloredo was able to support him in time! Even though he shared the same fate soon, he decided to hide his injury until the positions of allied forces were finally secured. ✊

In the mean time on Schwarzenberg’s left side we can see a fancy cavalry man - count Ignácz Gyulay, another veteran general.

He practically had one job - to stop Napoleon from escaping Leipzig by blocking the western route.

Did he succeed?

Well, to some extent...

It was not enough though.

But, despite some disappointment, we’ve practically collected them all! Czechs, Germans, an Italian and now a Hungarian! Austrian Empire at it’s finest as usual. ✨

And to top this enormous cake with a sweet cherry, I present to you a complete shot in a dark - this ironical looking military man could be Johann von Klenau, one more field marshal to go! His efforts actually saved the whole battle on it’s first day, since he blocked Murat’s fierce cavalry charge and prevented MacDonald’s from flanking the main army (classic Napoleon’s strategy sense I here, heh).

Now that’s what we call a nice save!

And with this small but important victory which can sometimes change the whole course of events I would love to conclude my vast reflection on the Kraft’s painting. It’s a true masterpiece when it comes to all the tiny details and portrayals of the heroes from a distance past.

Thank you all from the bottom of my heart for your attention to the matter!

(Hope you liked it as well, @microcosme11! That was an incredible opportunity, thank you very much! It’s always a pleasure to dig into all these small nuances and facts. 😌)

Das Ende ❤️🤍❤️

#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#battle of leipzig#völkerschlacht bei leipzig#karl zu schwarzenberg#hieronymus von colloredo-mansfeld#friedrich VI von hessen-homburg#ignácz gyulay#johann von klenau#austrian empire#austrian history#19th century

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Ulm on 16th – 19th October, 1805 was a series of skirmishes, at the end of the Ulm Campaign, which allowed Napoleon I to trap an entire Austrian army under the command of Karl Freiherr Mack von Leiberich with minimal losses and to force its surrender near Ulm in the Electorate of Bavaria.

In 1805, the United Kingdom, the Austrian Empire, Sweden, and the Russian Empire formed the Third Coalition to overthrow the French Empire. When Bavaria sided with Napoleon, the Austrians, 72,000 strong under Mack, prematurely invaded while the Russians were still marching through Poland.

Napoleon had 177,000 troops of the Grande Armée at Boulogne, ready to invade England.

They marched south on 27th August and by 24th September were ready to cross the Rhine from Mannheim to Strasbourg. After crossing the Rhine, the greater part of the French army made a gigantic right wheel so that its corps reached the Danube simultaneously, facing south.

On 7th October, Mack learned that Napoleon planned to cross the Danube and march around his right flank so as to cut him off from the Russians who were marching via Vienna. He accordingly changed front, placing his left at Ulm and his right at Rain, but the French went on and crossed the Danube at Neuburg, Donauwörth, and Ingolstadt.

Unable to stop the French avalanche, Michael von Kienmayer's Austrian corps abandoned its positions along the river and fled to Munich.

On 8th October, Franz Auffenberg's division was cut to pieces by Joachim Murat's Cavalry Corps and Jean Lannes' V Corps at the Battle of Wertingen.

The following day, Mack attempted to cross the Danube and move north. He was defeated in the Battle of Günzburg by Jean-Pierre Firmin Malher's division of Michel Ney's VI Corps which was still operating on the north bank.

During the action, the French seized a bridgehead on the south bank. After first withdrawing to Ulm, Mack tried to break out to the north. His army was blocked by Pierre Dupont de l'Etang's VI Corps division and some cavalry in the Battle of Haslach-Jungingen on 11th October.

By the 11th, Napoleon's corps were spread out in a wide net to snare Mack's army. Nicolas Soult's IV Corps reached Landsberg am Lech and turned east to cut off Mack from Tyrol.

Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte's I Corps and Louis Nicolas Davout's III Corps converged on Munich. Auguste Marmont's II Corps was at Augsburg. Murat, Ney, Lannes, and the Imperial Guard began closing in on Ulm. Mack ordered the corps of Franz von Werneck to march northeast, while Johann Sigismund Riesch covered its right flank at Elchingen. The Austrian commander sent Franz Jellacic's corps south toward Tyrol and held the remainder of his army at Ulm.

On 14th October, Ney crushed Riesch's small corps at the Battle of Elchingen and chased its survivors back into Ulm. Murat detected Werneck's force and raced in pursuit with his cavalry. Over the next few days, Werneck's corps was overwhelmed in a series of actions at Langenau, Herbrechtingen, Nördlingen, and Neresheim. On 18th October, he surrendered the remainder of his troops. Only Archduke Ferdinand Karl Joseph of Austria-Este and a few other generals escaped to Bohemia with about 1,200 cavalry.

Meanwhile, Soult secured the surrender of 4,600 Austrians at Memmingen and swung north to box in Mack from the south. Jellacic slipped past Soult and escaped to the south only to be hunted down and captured in the Capitulation of Dornbirn in mid-November by Pierre Augereau's late-arriving VII Corps. By 16th October, Napoleon had surrounded Mack's entire army at Ulm, and four days later Mack surrendered with 25,000 men, 18 generals, 65 guns, and 40 standards.

Some 20,000 escaped, 10,000 were killed or wounded, and the rest made prisoner.

About 500 French were killed and 1,000 wounded, a low number for such a decisive battle.

In less than 15 days the Grande Armée neutralized 60,000 Austrians and 30 generals. At the surrender (known as the Convention of Ulm), Mack offered his sword and presented himself to Napoleon as "the unfortunate General Mack". Mack was court-martialed and sentenced to two years' imprisonment.

(Information From Wikipedia)

0 notes

Note

If you did an Oscars ceremony for 18th century armies what categories you would have eg. Best light infantry and who would win the awards for each category?

Quite a fun question actually.

Artillery: Without doing the British or Austrian artillery dirty, it's a showdown between France and Prussia for this one (like most of the awards really). The French started pretty strong, but Frederick the Great made vital breakthroughs especially in the use of light and horse artillery. But the Gribeauval system introduced around the time of the American Revolution laid the foundations for Napoleon to excel, so overall France wins this one.

Cavalry: Honestly I'm not hugely proficient on who had the best cavalry over the course of the century (besides the fact it definitely wasn't Britain). France, Prussia or Austria could all take this.

Infantry: Again, it's between France and Prussia. The latter during the Seven Years War gives them a big advantage, but the effectiveness of French infantry during the French Revolution/start of the Napoleonic era claws it back. I think Prussia just takes this one, based mainly on the fact that French reforms adopted lots of the Prussian system after 1763. If the timeline ran to 1815 France would win it. Special mention to Britain though, their win/loss ratio in toe-to-toe line engagements is impressive.

Grenadiers: Really I can't choose here as every nation's grenadiers were pretty badass.

Light Infantry: In terms of light infantry as part of the standing army, I think Britain takes this. They were developed very effectively in the Seven Years War, and they did practically all the hardest fighting during the American Revolution. France comes a pretty close second with Napoleon's great use of skirmisher spam, they really weaponised the light infantry "cloud," but does it really count if you don't have any rifles at all?

Generals and General Staff: This again comes down to France vs Prussia, with France's development of a staff corps from the 1770s onwards winning it for them.

Auxiliaries: The Russians get cossacks, the Austrians Grenzers, the British and French Native Americans. France wins out due to basically running the whole of the North American side of the Seven Years War based on Native allies, offsetting the huge population disparity there and drawing the war out much longer than it potentially should have lasted. Britain coming in second place with the use of Native allies during the Revolution, it wasn't war-winning but it helped the Crown effort a lot more than is popularly realised.

Best Overall Army: A clash between France and Prussia. France coming down a bit off 17th c. domination, a slightly patchy record in the first half of the century but still consistently the most formidable European military. Prussia knocks it out of the park in the Seven Years War, France recovers during the American Revolution and goes on to maintain the title of most powerful European army via the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

Results:

France: 4

Prussia: 1

Britain: 1

31 notes

·

View notes