#Bess Lomax

Text

Love for the Lomax Legacy

Lovers of American folk music know and revere the name of Lomax. For over a century and four generations this family has devoted itself to the discovery, preservation, and dissemination of the People’s Voice.

It began with John A. Lomax (1867-1948). Raised on a Texas farm, with roots in Mississippi and North Carolina, Lomax brought the farm ethic of dawn-to-dusk hard work to the project of…

View On WordPress

#Alan Lomax#American Folks Music#archive#author#Bess Lomax#collector#folk#John Lomax#Library of Congress#producer

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mike Seeger

source: https://www.arts.gov/honors/heritage/mike-seeger

#vintage banjo#fivestringbanjo#gourd banjo#mike seeger#old time music#national endowment for the arts

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Almena Lomax (July 23, 1915 - March 25, 2011) was a leader in African American journalism and founded a Black weekly newspaper in Los Angeles. She was the first Black person to work on the city desk of the San Francisco Chronicle.

She was born in Galveston, Texas. Her father was a postal deliveryman and her mother was a full-time seamstress. In 1917 the Davis family relocated to Chicago before settling in California in the early 1920s.

She graduated from Jordan High School and enrolled in Los Angeles City College where she majored in journalism. She graduated and was hired by editor Charlotta Bass to work for the African American weekly The California Eagle. She worked at a local Los Angeles radio station, where she ran a news/interview broadcast program two times a week.

She acquired a loan from her father-in-law, Lucius W. Lomax Sr., enabling her to start her newspaper, The Los Angeles Tribune. She married Lucius W. Lomax Jr. and the couple had six children before the marriage ended in 1960.

She was a delegate to the DNC. She traveled to Montgomery to write about the ongoing Montgomery Bus Boycott and the emerging Civil Rights Movement. She led protests against an array of Hollywood motion pictures that she and others felt promoted damaging representations of African Americans. Two of those films were Porgy and Bess and Imitation of Life.

After the divorce, she moved with her six children to Tuskegee. She continued to write articles for national magazines such as The Nation. She returned to California and wrote for the San Francisco Chronicle and the San Francisco Examiner. She continued to write on political and social events into the 1990s.

Her daughter Melanie became the president of the Los Angeles Police Commission and a prominent civil rights attorney. Her daughter Michele was a film critic at the San Francisco Examiner. Her son Michael is the national president and CEO of the United Negro College Fund and her son Mark is a Los Angeles attorney. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note

Text

#the almanac singers#woody guthrie#pete seeger#cisco houston#sis cunningham#bess lomax#folk#folk music#*mypost

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

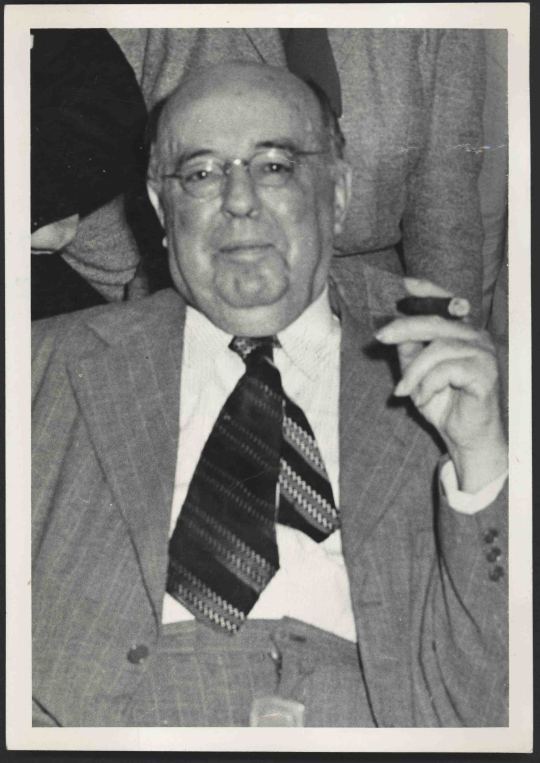

Today we remember the passing of John Avery Lomax I who died January 26, 1948 in Greenville, Mississippi

John Avery Lomax I was an American teacher, a pioneering musicologist, and a folklorist who did much for the preservation of American folk music. He was the father of Alan Lomax (also a distinguished collector of folk music) and Bess Lomax Hawes.

The Lomax family originally came from England with William Lomax, who settled in Rockingham County in what was then "the colony of North Carolina." John Lomax was born in Goodman in Holmes County in central Mississippi, to James Avery Lomax and the former Susan Frances Cooper. In December 1869, the Lomax family traveled by ox cart from Mississippi to Texas. John Lomax grew up in central Texas, just north of Meridian in rural Bosque County. His father raised horses and cattle and grew cotton and corn on the 183 acres (0.74 km2) of bottomland that he had purchased near the Bosque River. He was exposed to cowboy songs as a child. At around nine he befriended Nat Blythe, a former slave hired as a farmhand by James Lomax. The friendship, he wrote later, "perhaps gave my life its bent." Lomax, whose own schooling was sporadic because of the heavy farmwork he was forced to do, taught Blythe to read and write, and Blythe taught Lomax songs including "Big Yam Potatoes on a Sandy Land" and dance steps such as "Juba". When Blythe was 21 years old, he took his savings and left. Lomax never saw him again and heard rumors that he had been murdered. For years afterward, he always looked for Nat when he traveled around the South

Through a grant from the American Council of Learned Societies, Lomax was able to set out in June 1933 on the first recording expedition under the Library's auspices, with Alan Lomax (then eighteen years old) in tow. As now, a disproportionate percentage of African American males were held as prisoners. Robert Winslow Gordon, Lomax's predecessor at the Library of Congress, had written (in an article in the New York Times, c. 1926) that, "Nearly every type of song is to be found in our prisons and penitentiaries" Folklorists Howard Odum and Guy Johnson also had observed that, "If one wishes to obtain anything like an accurate picture of the workaday Negro he will surely find his best setting in the chain gang, prison, or in the situation of the ever-fleeing fugitive." But what these folklorists had merely recommended John and Alan Lomax were able to put into practice. In their successful grant application they wrote, following Odum, Johnson and Gordon's hint, that prisoners, "Thrown on their own resources for entertainment ... still sing, especially the long-term prisoners who have been confined for years and who have not yet been influenced by jazz and the radio, the distinctive old-time Negro melodies." They toured Texas prison farms recording work songs, reels, ballads, and blues from prisoners such as James "Iron Head" Baker, Mose "Clear Rock" Platt, and Lightnin' Washington. By no means were all of those whom the Lomaxes recorded imprisoned, however: in other communities, they recorded K.C. Gallaway and Henry Truvillion.

In July 1933, they acquired a state-of-the-art, 315 pounds (143 kg) phonograph uncoated-aluminum disk recorder. Installing it in the trunk of his Ford sedan, Lomax soon used it to record, at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, a twelve-string guitar player by the name of Huddie Ledbetter, better known as "Lead Belly," whom they considered one of their most significant finds. During the next year and a half, father and son continued to make disc recordings of musicians throughout the South.

John A. Lomax's contribution to the documentation of American folk traditions extended beyond the Library of Congress Music Division through his involvement with two agencies of the Works Progress Administration. In 1936, he was assigned to serve as an advisor on folklore collecting for both the Historical Records Survey and the Federal Writers' Project. Lomax's biographer, Nolan Porterfield, notes that the outlines of the famed WPA State Guides resulting from this work resemble Lomax and Benedict's earlier Book of Texas.

Upon Lomax's departure this work was continued by Benjamin A. Botkin, who succeeded Lomax as the Project's folklore editor in 1938, and at the Library in 1939, resulting in the invaluable compendium of authentic slave narratives: Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery, edited by B. A. Botkin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945).

John A. Lomax served as president of the Texas Folklore Society for the years 1940–41, and 1941–42. In 1947 his autobiography Adventures of a Ballad Hunter (New York: Macmillan) was published and was awarded the Carr P. Collins prize as the best book of the year by the Texas Institute of Letters. The book was immediately optioned to be made into a Hollywood movie starring Bing Crosby as Lomax and Josh White as Lead Belly, but the project was never realized.

In 1932, Lomax met his friend, Henry Zweifel, a rancher and businessman then from Cleburne in Johnson County, while both were volunteers for Orville Bullington's Republican gubernatorial race against the Democrat Miriam Ferguson. Lomax's old enemy, James Ferguson, was virtually running his wife's comeback attempt at the governorship.

Lomax died of a stroke at the age of eighty in January 1948. On June 15 of that year, Lead Belly gave a concert at the University of Texas, performing children's songs such as "Skip to My Lou" and spirituals (performed with his wife Martha) that he had first sung years before for the late collector.

In 2010, John A. Lomax was inducted into the Western Music Hall of Fame for his contributions to the field of cowboy music.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

30-Day Song Challenge, Day 29: A song you remember from your childhood.

But did he ever return? No, he never returned

And his fate is still unlearned

(Shame and scandal)

He may ride forever 'neath the streets of Boston

He's the man who never returned

(The Kingston Trio, “M.T.A.” - written by Jacqueline Steiner and Bess Lomax Hawes!)

#30 day song challenge#1950s music#no i am not actually this old#but my parents had their old records and zero patience for contemporary radio#so i was the only second grader who listed one of her fave bands as#the kingston trio#village-skeptic irl#bb skeptic

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

I just added a sixth song to songs Poet Scarlett needs to know about Boston.

Post here

The additon is:

The Kingston Trio-MTA Charlie

A song from 1949 by Jacqueline Steiner and Bess Lomax Hawes.

Known informally as "Charlie on the MTA", the song's lyrics tell of a man named Charlie trapped on Boston's subway system.

The song became a hit in 1959 when recorded and released by the Kingston Trio, an American folk group.

The song has become so entrenched in Boston lore that the Boston area transit authority named its electronic card based fare collection system the "Charlie Card" as a tribute to this song.

The transit organization, now called the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), held a dedication ceremony for the card system in 2004 which featured a performance of the song by the Kingston Trio and then-governor Mitt Romney.

Did everyone understand the references or lyrics to the other songs?

The Standells-Dirty Water

for Boston Harbor when it was polluted in the 1960′s.

Written by The Standells producer Ed Cobb. The song's Boston and Charles River references are reportedly based on an experience of Cobb and his girlfriend with a mugger in Boston in the mid-1960′s

Also "Frustrated women ... have to be in by twelve o'clock", colleges had curfews for women— and a passing mention of the Boston Strangler — "have you heard about the Strangler? (I'm the man I'm the man)” at the end of song.

"Dirty Water" is beloved by the city of Boston and its sports fans. The song is traditionally played by Boston sports teams following victories. The song is now played not only at Red Sox games, but also those of the Boston Celtics, and the Boston Bruins.

In 1997, "Dirty Water" was decreed the "official victory anthem" of the Red Sox, and is played after every home victory won by the Boston Red Sox.

The surviving Standells have performed the song at Fenway Park from atop the Green Monster.

Also, in 1997 two Boston area music-related chain stores celebrated their joint 25th anniversary by assembling over 1500 guitarists, plus a handful of singers and drummers, to perform "Dirty Water" for over 76 minutes at the Hatch Shell adjacent to the Charles River.

In 2007, "Dirty Water, as sung by the Standells" was honored by official decree of The Massachusetts General Court.

Neil Diamond-Sweet Caroline

The song has been played at Fenway Park, home of Major League Baseball's Boston Red Sox, since at least 1997, and in the middle of the eighth inning at every game since 2002.

On opening night of the 2010 season at Fenway Park, the song was performed by Diamond himself.

In a 2007 interview, Diamond stated the inspiration for his song was John F. Kennedy's daughter, Caroline, who was eleven years old at the time it was released.

Diamond sang the song to her at her 50th birthday celebration in 2007.

In December 21, 2011, in an interview on CBS's The Early Show, Diamond said that a magazine cover photo of Caroline Kennedy as a young child on a horse with her parents in the background created an image in his mind, and the rest of the song came together about five years after seeing the picture.

However, in 2014 Diamond said the song was about his then-wife Marcia, but he needed a three-syllable name to fit the melody.

Neil Diamond performing song at 1st Home game at Fenway Park after the Boston Marathon bombings here

I'm Shipping Up to Boston-Dropkick Murphys

is a song with lyrics written by the folk singer Woody Guthrie. The lyrics from the song were taken from a fragment of paper that was found whilst looking through Woody Guthrie's archives.

The song's simple lyrics describe a sailor who had lost a prosthetic leg climbing the topsail, and is shipping up to Boston to "find my wooden leg."

The Dropkick Murphys put music to the lyrics.

The song gained world-wide attention along with boosting the band's popularity for its use in the 2006 Academy Award-winning Best Picture, The Departed.

The Departed was filmed in Boston.

Ozzy Osbourne-Crazy Train

The New England Patriots football team entrance anthem.

See Ozzy perform song here for the opening of 2005 NFL season

Areosmith-Dream On

They hail from Boston.

1 note

·

View note

Audio

When watching the Bob Dylan documentary "No Direction Home", I was struck by something Dylan said when talking about Woody Guthrie. He said when he first heard Woody, he was impressed by his sound, the sound of the records. He goes on to talk about the lyrics of the songs, but his first mention was the performance. In the many years I have followed Bob, I have had numerous people tell me that they like his songs, but not his voice, that they like to hear others sing them. I have never agreed with that, I believe Dylan is his own best interpreter. The same can be said for Woody, generally regarded as a great songwriter, but overlooked as a performer. For me, a good counter argument is Ramblin' Jack Elliott, who slavishly imitated Guthrie early in his career. Jack doesn't do a lot of political material, which is what most remember of Woody, but he has never moved away from the rough and tumble sound of Guthrie's originals. I once heard Jack say that he hated to hear others sing Woody, because they try to hard, He goes on to say "it's not opera." Jack’s take on “Buffalo Skinners” is an epic example.

youtube

It's well known that in his early days in The Village, that Dylan mimicked Jack as much as he did Woody, and I believe that it was the performance style of Guthrie that impressed him them both the most. Back in the nineties, Smithsonian Folkways Records put out a four part set on Woody, each volume focusing on a particular aspect of his career. Volume 2 was titled "Mule Skinner Blues" and features Guthrie doing traditional and country stuff. I've always loved the disc, and one reason is that Woody as a poet is absent, he is doing material that was around before he came on the scene. On a couple of numbers, he even plays the fiddle. In this context, Woody is part of a tradition of early hillbilly recordings, standing apart from others, but still fitting into the genre. If you listen to this, and then the Carter Family, the link is plain. It's also important to note that although his version of the title track may be inferior to Jimmie Rodgers or Bill Monroe, it was his take on the song that was first heard by folkies, influencing many of the subsequent versions. Much of the stuff on "Mule Skinner Blues" is taken from sessions done in the spring of 1944, well oiled affairs where Woody is joined at times by Cisco Houston, Sonny Terry, Pete Seeger and Bess Lomax.

youtube

Some of the material is sloppy, sounding like an unrehearsed, drunken hootenanny. I believe, however, that it was that sound that ends up being so influential. These recordings were not carefully prepared, but rather impromptu performances of songs they came up with during the sessions. The very nature of that kind of playing gives the records an immediacy that rails against professionally recorded music. There is an intimacy about a performance that was so spontaneous that it will literally never sound that way again that gives these cuts their power. It's obvious that this is the sound the young Bob Dylan and so many others have been influenced by for all these years. Guthrie always had a lot to say, but it's important to pay attention to the way he said it, which was also influential. Woody may have just been doing these sides for the studio fee, but in the process, he ended up making timeless music.

youtube

0 notes

Link

"A scholar, teacher, performer, writer, and filmmaker, Bess established and stewarded the Folk and Traditional Arts program at the National Endowment for the Arts, thus creating a national network of arts organizations to advocate for traditional arts."

Bess Lomax Hawes Digital Collection Launches | Folklife Today

Bess Lomax Hawes Digital Collection Launches. A blog post at "Folklife Today" on 2020-04-22.

0 notes

Text

RIP Jacqueline Steiner, 94, Lyricist Left Charlie on the M.T.A. "But did he ever return, no he never returned And his fate is still unlearned He will ride forever Neath the streets of Boston He's he man who never returned." wrote w Bess Lomax Hawes about a Boston politician. https://t.co/mmkpKljbko

RIP Jacqueline Steiner, 94, Lyricist Left Charlie on the M.T.A.

"But did he ever return,

no he never returned

And his fate is still unlearned

He will ride forever

Neath the streets of Boston

He's he man who never returned."

wrote w Bess Lomax Hawes about a Boston politician. pic.twitter.com/mmkpKljbko

— DenisCampbell (@ClientLoyaltyDC) February 5, 2019

from Twitter https://twitter.com/ClientLoyaltyDC

February 05, 2019 at 10:06PM

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

A LABOR STRIKE and a heart-wrenching tragedy in 1913, Woody Guthrie at a hootenanny in a New York basement in 1945, and Bob Dylan in a recording studio in 1962 — these three seemingly unrelated events provide the framework for Daniel Wolff’s study of industrial violence in the United States, the folk music revival, and the evolution of rock ’n’ roll. Wolff’s narrative is an angry polemic and social commentary. The “mysteries” he explores reveal how economic depression, foreign wars, and racial discrimination shaped the music of two restless and fiery artists. Along the way, he delves into the world of copper mining, revising the official version of the 1913 tragedy in order to set the record straight.

Labor disputes and industrial disasters are not particularly unusual events in American history, but the macabre deaths of 74 people (60 of whom were children between the ages of two and 16) on Christmas Eve in a tall, jammed stairwell of the Italian Hall in strike-ridden Red Jacket, Michigan, in 1913 (renamed Calumet in 1929) was no ordinary catastrophe. Several thousand underground copper miners, mostly Finnish and Italian immigrants, had been on strike for more than six months, but they were running out of strike funds and faced a powerful business-led Citizens’ Alliance. As Christmas drew near, the mining union’s Women’s Auxiliary organized a big Christmas party to make sure that every child of a striking miner would receive a holiday gift. Hundreds of children and parents climbed up the high steps to the second floor ballroom of the Italian Hall and gathered around a large Christmas tree. A young girl played a piano and the crowd quieted down to listen. Although there remains a dispute as to what happened next, it is clear that some person or persons yelled, “Fire!” and that this provoked a mad stampede for the stairwell. Many children tripped and fell headlong down the steep stairs, landing with broken bones in front of the doors. For some reason, the doors would not open. The strikers claimed the anti-union thugs hired by the Alliance held the doors shut; the Alliance later claimed the doors opened to the inside. As more and more tried to escape, the stairway became jammed with panic-stricken children who piled on top of each other, breaking their painfully entangled arms and legs. Soon they began to suffocate. When the doors were finally opened, 74 bodies were carried back up the stairs and laid in rows by the Christmas tree.

The Keweenaw Peninsula is a 70-mile finger of land that juts into Lake Superior at the northernmost point of the state of Michigan. I stepped on the gas pedal and pushed my Chevrolet up to 55, heading south from Copper Harbor, the small town at the top of the peninsula. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is physically separated from the rest of Michigan by the Straits of Mackinac and when you look at a map of the United States you might say, with perfect logic, that the Upper Peninsula really should be part of Wisconsin. Most of the UP is scenic northern forest, but wild, rugged, and largely undeveloped. I’m sure more wolverines live in the UP than humans, but they don’t get counted in the census. US Highway 41 is a six-lane freeway in Milwaukee, but up on the Keweenaw Peninsula it is a narrow two-lane road with tall pine trees standing like soldiers along the edge of the asphalt. Rounding a sharp turn, I suddenly saw five or six whitetail deer directly in front of me. I swerved and missed most of them, but one deer jumped in the same direction as my car, smashed into the hood, broke the windshield, flew over the top, and dashed into the forest. The car was not drivable. After a half hour or so, a Highway Patrolman pulled up to offer assistance. “It happens all the time,” he said. “There are a lot of deer and it can be hard to see them.” He called a tow truck and soon my damaged car was on its way to Snow’s Auto Repair in Calumet, Michigan.

Wolff contextualizes the story of 1913 in a comprehensive history of copper mining in the Upper Peninsula. Native Americans mined copper and used it to make hooks, knives, and jewelry. French explorers and Jesuit missionaries discovered new uses for copper, prospectors searched for more, and industrialists from the East invested large sums to go underground, recruiting thousands of immigrants from Wales, Russia, Italy, and Finland to drill and extract the ore. By reopening the historical record, Wolff resolves lingering mysteries about the tragedy:

Was there a fire? No.

Did someone actually yell “Fire!”? No one ever confessed to it.

Did the strikebreakers deliberately hold the door shut to prevent the children from leaving? No one claimed to have seen anyone hold the doors shut, although the strikers and their families were inside the building.

Did the doors at the bottom of the steps open to the inside, as is so often repeated in official descriptions of the tragedy? No.

It is these rumors and uncertainties that have passed for history, burying the truth under layers of obfuscation that anger Wolff and have led him toward Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. Woody Guthrie wrote (and rearranged) about 1,500 songs, but “1913 Massacre,” with its dark tone, solemnity, and dirge-like tempo, was a uniquely powerful piece of his repertoire. The dry humor and ironic double meanings often found in his compositions are jettisoned as Guthrie reports on the shockingly brutal facts in a matter-of-fact way. It suggests that the full extent of the horror sapped him of emotion. As Wolff correctly notes, we hear nothing about socialism or revolution or even unionism. Instead, Guthrie takes the listener along with him as an observer, a witness to what will unfold. “Take a trip with me back in 1913,” writes Guthrie.

Calumet, Michigan, in the copper country.

I will take you to a place called Italian Hall,

where the miners are having their Christmas ball.

I will take you in a door and up the high stairs,

singing and dancing is heard everywhere,

I’ll let you shake hands with the people you see,

and watch the kids dance around the big Christmas tree.

Guthrie crafted the song based on a memoir written by “Mother” Mary Bloor, an early Socialist and labor organizer well known in political circles for her courage in the face of repression and violence. Bloor’s daughter, Herta Geer, was the wife of Will Geer, the actor and political activist who had befriended Guthrie in Los Angeles in 1939 and introduced him to the local writers, actors, and musicians involved in the growing labor movement and the fight against fascism. Guthrie wrote the song in 1945, about five years after Bloor’s 300-page memoir, We Are Many, appeared. Although her section on Calumet is only a few pages long, it was crammed with detail, much of which Guthrie incorporated into his song.

Wolff uses “1913 Massacre” as an entry point into Guthrie’s life. Despite Guthrie’s self-created persona as the “Political Okie,” with his deliberate misspellings, improper grammar, and “aw shucks” demeanor, Guthrie was not an uncomplicated personality. As he writes his narrative of “1913 Massacre,” Wolff draws out some of those complexities. On the one hand, Guthrie’s situation in 1945 was more stable than ever. He had completed his military service and several tours in the Merchant Marine, and had survived a torpedoing. Working with Moe Asch he was recording scores of songs and beginning a new project called “American Documentary,” which he described as “a kind of musical newspaper,” using songs to illuminate and comment upon current events. His semi-autobiographical novel, Bound for Glory, had received 150 mostly positive reviews and encouraged Guthrie to begin a second novel, Seeds of Man. A song he had written in Los Angeles in 1939, “Oklahoma Hills,” recorded by his cousin Jack Guthrie, reached number one on the folk jukebox list in 1945. That same year, along with Pete Seeger and others, he founded People’s Songs. The United States and the Soviet Union remained united against the Axis powers, unions had made unprecedented progress during the war years, and organized labor emerged for the first time as an important political force at the national level.

But below the surface, Guthrie was troubled. His project with Moe Asch resulted in about 150 recordings, including collaborations with Seeger, Cisco Houston, Bess Lomax Hawes, and Sonny Terry, but the end product, an album entitled Struggle, was not widely distributed. A further recording effort, focused on Sacco and Vanzetti, also proved a disappointment. Wolff describes how Guthrie’s energy and focus began to wane as he succumbed to the debilitating disease that would devour him over the remaining 25 years of his life: “Just dizzy, woozy, blubberdy. And scubberdy and rustlety, tastely […] the soberest drunk I ever got on.” Guthrie’s disease was not accurately diagnosed as Huntington’s chorea until 1952, but he knew that the same inexorable force that had destroyed his mother now held him in its deadly grip. Even as he gathered with Seeger and others to form People’s Songs on New Year’s Eve, 1945, Guthrie must have been beset by deep anxiety. Wolff describes the scene:

They were trying to reinvent the movement, to survive the emerging Cold War, to preserve their hopes and ideals. The meeting soon turned into a hootenanny where everyone sang. When it was Guthrie’s turn, he could have launched into the punchy “Union Maid” or “Roll on, Columbia,” songs of confidence and optimism. Instead he sang a cautionary tune, that slow ballad about the miner’s Christmas that he was now calling 1913 Massacre.

Wolff notes that Guthrie’s productive years coincided almost exactly with the period of the Popular Front against fascism, from 1935 to 1945. That period had ended.

Through the windshield of the tow truck I saw a sign that read “Calumet, Michigan” and immediately recalled the song — a song that’s hard to forget. I had first encountered it on Arlo Guthrie’s album, Hobo’s Lullaby. I remember listening to the song and writing down the lyrics on a sheet of paper, lifting and dropping the needle of the record player a dozen times before I was able to capture all the words accurately. Then I sang the song to myself. And sang it again. And again.

Snow’s Auto Repair was located in the heart of what remained of Calumet after the copper veins were exhausted and the miners left for work out west. The year was 1988, but at Snow’s it seemed more like 1958. The sagging building, the forlorn signage, the old auto repair equipment, and the two elderly mechanics in dreary, oil-stained uniforms all recalled an earlier time. While I waited for the insurance adjuster to arrive and estimate the cost of repairs, I struck up a conversation with one of the mechanics.

“Say, can you tell me where the old Italian Hall is located?” I asked.

“The Italian Hall?” he responded.

“Yes, I’m sure it’s here. This is Calumet, right?”

“That’s right. This is Calumet.”

“Well, I’m just wondering where the Italian Hall is located. I’d like to see it.”

The mechanic raised his arm and pointed his work-worn index finger toward the window, in the direction of a large empty lot across the street. “That’s where it was. They tore it down last year. I guess you’re too late.”

Woody Guthrie appealed to KFVD radio listeners in Southern California and found a new audience among political activists, union organizers, and progressive writers who had never seen a bona fide Okie with left-wing politics. He cultivated his persona in songs, newspaper articles, and Bound for Glory. Even as he branched out into new areas, such as children’s song, Jewish songs, and novels and cartoons, the Okie persona never left him.

Wolff contrasts this with Bobby Zimmerman’s constant reinventions of himself. First the artist who would be Dylan abandoned his early interests in rock and blues for the emerging folk scene and changed his last name. Then, after discovering some Guthrie records from one of his folkie friends in the Dinkytown section of Minneapolis, he immersed himself in the Guthrie persona. He learned all of Guthrie’s songs and limited his performances at coffee houses and parties to the man’s repertoire. He mimicked Guthrie’s guitar style, speech patterns, and clothing. He carefully read Bound for Glory and began to create tall tales about his background, claiming that he was from Albuquerque or Gallup or Illinois — anywhere but Hibbing, Minnesota. “Dylan made himself authentic,” writes Wolff.

He changed who he was to get closer to the truth. Or try to. The sound that eventually came over pop radio — his timed drawl, the rural edge, the off-center sense of humor — was a lot Guthrie. That’s how Dylan became an original — through imitation. It’s as if he ran from his middle-class, mid-20th-century Hibbing and went back to Guthrie’s ’30s. Or as he put it, “I was making my own depression.”

Veteran folkies from the Dinkytown scene who were familiar with Guthrie chided Dylan for going too far with his impersonation. So Dylan went east to find Guthrie, claiming that he hopped freight trains and hitchhiked like Woody, when he actually got a ride from a friend. Dylan’s visits with a dying man in Greystone Hospital have been treated elsewhere, but Wolff captures an important element of this encounter. While Dylan was performing Guthrie’s songs for his idol, who was no longer able to speak, he confronted the reality that Guthrie was effectively gone, that his world of the Depression and his war against fascism had disappeared, that his fervent political dreams had vanished in the wind. Later Dylan would write:

Woody Guthrie was my last idol

he was the last idol because

he was the first idol

I’d ever met

that taught me

face t’ face

that men are men

shatterin’ even himself

as an idol …

Dylan’s confrontation with Guthrie’s demise was the starting point for Dylan’s composition of “Song to Woody,” written only a few days after their first meeting.

The song draws heavily upon Guthrie, using, almost note by note, the haunting, dirge-like melody of “1913 Massacre,” and opening with the line, “Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song,” which is derived from a similar opening Guthrie had used in a poem for Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. The song is a tribute but also a farewell. The lyrics set up comparisons between the Depression-era ’30s and the ’60s, between Guthrie’s old life and Dylan’s new life. “Listen to the song Dylan felt he needed to sing,” writes Wolff, “and you hear a kid who’s come a thousand miles only to discover that what he came for no longer exists.” The song is important for another reason: it marks the commencement of Bob Dylan, the singer-songwriter. Dylan’s first self-titled album included only two original songs — “Talkin’ New York,” a hillbilly’s satirical romp through the big city, and “Song to Woody.” Subsequent Dylan albums contained exclusively Dylan compositions.

Wolff may be right in locating the end of young Dylan’s idolization of Guthrie in “Song to Woody,” but the older folky continued to influence the younger artist. The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and The Times They Are a-Changin’ featured songs with powerful but artful political themes. While hardline politicos in the folk scene complained that Dylan’s songs about old girlfriends meant that he was turning his back on the struggle, those who listened closely to “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” and “The Times They are a-Changin’,” heard Dylan developing on the Guthrie tradition. Still, Dylan was carefully moving away from strictly political themes. Wolff quotes excerpts from a “letter back to Dinkytown,” which Dylan wrote for the 1963 Newport Folk Festival program, in which the artists refuses to answer the standard union organizing question posed in the powerful song written by Florence Patton Reece, “Which Side Are You On?”:

Hey man — I’m sorry —

…

the songs we used t sing an play

the songs written fifty years ago

the dirt farm songs — the dust bowl songs

the depression songs …

Woody’s songs …

when there was a strike there’s only two kind of views

… thru the union’s yes or thru the boss’s eyes

… them two simple sides that was so easy t tell apart

[have become]

A COMPLICATED CIRCLE.

The folk songs showed me the way

an I got nothing but homage an holy thinkin’ for the ol songs and stories

singin an writin what’s on my own mind …

not by no kind of side

not by no kind a category.

Dylan was preparing to reinvent himself again and he was not taking sides.

I turned to the mechanic at Snow’s and asked, “Where are the bricks?”

“What bricks?

“Well, the Italian Hall was made of bricks and they demolished it. So, what did they do with the bricks?”

“They hauled them away.”

“Yeah, but where did they go?”

“You want to know where the brinks are now?”

“Yes, where did they dump the bricks? Do you know?”

“Well, I don’t know why you want to know, but yeah, I know where they dumped them, sure.” He pointed out the window again. “Okay, go north for two stop lights. Then turn left and go until you get to the railroad tracks. Cross the tracks and take the first turn to the left. Keep going about a quarter mile until you see an island of poplar trees on the left. Then take the dirt road on the right for, I don’t know, a hundred yards or so. You’ll see a pile of bricks. If that’s what you’re looking for, that’s where you will find them.”

About a year later I was asked to perform in a Labor Concert in Kenosha, Wisconsin, along with Woody’s son, Arlo. I told Arlo I had learned the song “1913 Massacre” from his recording and that I wanted to give him a brick from the Italian Hall — a reminder of how our past can reemerge from under the weight of obfuscation.

Like the miners of Red Jacket, Michigan, who extracted copper from deep below the surface of the earth, Wolff helps us recover the truth about a tragic episode in our history.

¤

Darryl Holter is a historian, entrepreneur, musician, and owner of an independent bookstore. He has taught history at the University of Wisconsin and UCLA and is an adjunct professor at USC.

The post “I’ll Take You to a Place Called Italian Hall”: On Daniel Wolff’s “Grown-Up Anger” and the Calumet Massacre of 1913 appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2yvkoPA

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

A LABOR STRIKE and a heart-wrenching tragedy in 1913, Woody Guthrie at a hootenanny in a New York basement in 1945, and Bob Dylan in a recording studio in 1962 — these three seemingly unrelated events provide the framework for Daniel Wolff’s study of industrial violence in the United States, the folk music revival, and the evolution of rock ’n’ roll. Wolff’s narrative is an angry polemic and social commentary. The “mysteries” he explores reveal how economic depression, foreign wars, and racial discrimination shaped the music of two restless and fiery artists. Along the way, he delves into the world of copper mining, revising the official version of the 1913 tragedy in order to set the record straight.

Labor disputes and industrial disasters are not particularly unusual events in American history, but the macabre deaths of 74 people (60 of whom were children between the ages of two and 16) on Christmas Eve in a tall, jammed stairwell of the Italian Hall in strike-ridden Red Jacket, Michigan, in 1913 (renamed Calumet in 1929) was no ordinary catastrophe. Several thousand underground copper miners, mostly Finnish and Italian immigrants, had been on strike for more than six months, but they were running out of strike funds and faced a powerful business-led Citizens’ Alliance. As Christmas drew near, the mining union’s Women’s Auxiliary organized a big Christmas party to make sure that every child of a striking miner would receive a holiday gift. Hundreds of children and parents climbed up the high steps to the second floor ballroom of the Italian Hall and gathered around a large Christmas tree. A young girl played a piano and the crowd quieted down to listen. Although there remains a dispute as to what happened next, it is clear that some person or persons yelled, “Fire!” and that this provoked a mad stampede for the stairwell. Many children tripped and fell headlong down the steep stairs, landing with broken bones in front of the doors. For some reason, the doors would not open. The strikers claimed the anti-union thugs hired by the Alliance held the doors shut; the Alliance later claimed the doors opened to the inside. As more and more tried to escape, the stairway became jammed with panic-stricken children who piled on top of each other, breaking their painfully entangled arms and legs. Soon they began to suffocate. When the doors were finally opened, 74 bodies were carried back up the stairs and laid in rows by the Christmas tree.

The Keweenaw Peninsula is a 70-mile finger of land that juts into Lake Superior at the northernmost point of the state of Michigan. I stepped on the gas pedal and pushed my Chevrolet up to 55, heading south from Copper Harbor, the small town at the top of the peninsula. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is physically separated from the rest of Michigan by the Straits of Mackinac and when you look at a map of the United States you might say, with perfect logic, that the Upper Peninsula really should be part of Wisconsin. Most of the UP is scenic northern forest, but wild, rugged, and largely undeveloped. I’m sure more wolverines live in the UP than humans, but they don’t get counted in the census. US Highway 41 is a six-lane freeway in Milwaukee, but up on the Keweenaw Peninsula it is a narrow two-lane road with tall pine trees standing like soldiers along the edge of the asphalt. Rounding a sharp turn, I suddenly saw five or six whitetail deer directly in front of me. I swerved and missed most of them, but one deer jumped in the same direction as my car, smashed into the hood, broke the windshield, flew over the top, and dashed into the forest. The car was not drivable. After a half hour or so, a Highway Patrolman pulled up to offer assistance. “It happens all the time,” he said. “There are a lot of deer and it can be hard to see them.” He called a tow truck and soon my damaged car was on its way to Snow’s Auto Repair in Calumet, Michigan.

Wolff contextualizes the story of 1913 in a comprehensive history of copper mining in the Upper Peninsula. Native Americans mined copper and used it to make hooks, knives, and jewelry. French explorers and Jesuit missionaries discovered new uses for copper, prospectors searched for more, and industrialists from the East invested large sums to go underground, recruiting thousands of immigrants from Wales, Russia, Italy, and Finland to drill and extract the ore. By reopening the historical record, Wolff resolves lingering mysteries about the tragedy:

Was there a fire? No.

Did someone actually yell “Fire!”? No one ever confessed to it.

Did the strikebreakers deliberately hold the door shut to prevent the children from leaving? No one claimed to have seen anyone hold the doors shut, although the strikers and their families were inside the building.

Did the doors at the bottom of the steps open to the inside, as is so often repeated in official descriptions of the tragedy? No.

It is these rumors and uncertainties that have passed for history, burying the truth under layers of obfuscation that anger Wolff and have led him toward Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. Woody Guthrie wrote (and rearranged) about 1,500 songs, but “1913 Massacre,” with its dark tone, solemnity, and dirge-like tempo, was a uniquely powerful piece of his repertoire. The dry humor and ironic double meanings often found in his compositions are jettisoned as Guthrie reports on the shockingly brutal facts in a matter-of-fact way. It suggests that the full extent of the horror sapped him of emotion. As Wolff correctly notes, we hear nothing about socialism or revolution or even unionism. Instead, Guthrie takes the listener along with him as an observer, a witness to what will unfold. “Take a trip with me back in 1913,” writes Guthrie.

Calumet, Michigan, in the copper country.

I will take you to a place called Italian Hall,

where the miners are having their Christmas ball.

I will take you in a door and up the high stairs,

singing and dancing is heard everywhere,

I’ll let you shake hands with the people you see,

and watch the kids dance around the big Christmas tree.

Guthrie crafted the song based on a memoir written by “Mother” Mary Bloor, an early Socialist and labor organizer well known in political circles for her courage in the face of repression and violence. Bloor’s daughter, Herta Geer, was the wife of Will Geer, the actor and political activist who had befriended Guthrie in Los Angeles in 1939 and introduced him to the local writers, actors, and musicians involved in the growing labor movement and the fight against fascism. Guthrie wrote the song in 1945, about five years after Bloor’s 300-page memoir, We Are Many, appeared. Although her section on Calumet is only a few pages long, it was crammed with detail, much of which Guthrie incorporated into his song.

Wolff uses “1913 Massacre” as an entry point into Guthrie’s life. Despite Guthrie’s self-created persona as the “Political Okie,” with his deliberate misspellings, improper grammar, and “aw shucks” demeanor, Guthrie was not an uncomplicated personality. As he writes his narrative of “1913 Massacre,” Wolff draws out some of those complexities. On the one hand, Guthrie’s situation in 1945 was more stable than ever. He had completed his military service and several tours in the Merchant Marine, and had survived a torpedoing. Working with Moe Asch he was recording scores of songs and beginning a new project called “American Documentary,” which he described as “a kind of musical newspaper,” using songs to illuminate and comment upon current events. His semi-autobiographical novel, Bound for Glory, had received 150 mostly positive reviews and encouraged Guthrie to begin a second novel, Seeds of Man. A song he had written in Los Angeles in 1939, “Oklahoma Hills,” recorded by his cousin Jack Guthrie, reached number one on the folk jukebox list in 1945. That same year, along with Pete Seeger and others, he founded People’s Songs. The United States and the Soviet Union remained united against the Axis powers, unions had made unprecedented progress during the war years, and organized labor emerged for the first time as an important political force at the national level.

But below the surface, Guthrie was troubled. His project with Moe Asch resulted in about 150 recordings, including collaborations with Seeger, Cisco Houston, Bess Lomax Hawes, and Sonny Terry, but the end product, an album entitled Struggle, was not widely distributed. A further recording effort, focused on Sacco and Vanzetti, also proved a disappointment. Wolff describes how Guthrie’s energy and focus began to wane as he succumbed to the debilitating disease that would devour him over the remaining 25 years of his life: “Just dizzy, woozy, blubberdy. And scubberdy and rustlety, tastely […] the soberest drunk I ever got on.” Guthrie’s disease was not accurately diagnosed as Huntington’s chorea until 1952, but he knew that the same inexorable force that had destroyed his mother now held him in its deadly grip. Even as he gathered with Seeger and others to form People’s Songs on New Year’s Eve, 1945, Guthrie must have been beset by deep anxiety. Wolff describes the scene:

They were trying to reinvent the movement, to survive the emerging Cold War, to preserve their hopes and ideals. The meeting soon turned into a hootenanny where everyone sang. When it was Guthrie’s turn, he could have launched into the punchy “Union Maid” or “Roll on, Columbia,” songs of confidence and optimism. Instead he sang a cautionary tune, that slow ballad about the miner’s Christmas that he was now calling 1913 Massacre.

Wolff notes that Guthrie’s productive years coincided almost exactly with the period of the Popular Front against fascism, from 1935 to 1945. That period had ended.

Through the windshield of the tow truck I saw a sign that read “Calumet, Michigan” and immediately recalled the song — a song that’s hard to forget. I had first encountered it on Arlo Guthrie’s album, Hobo’s Lullaby. I remember listening to the song and writing down the lyrics on a sheet of paper, lifting and dropping the needle of the record player a dozen times before I was able to capture all the words accurately. Then I sang the song to myself. And sang it again. And again.

Snow’s Auto Repair was located in the heart of what remained of Calumet after the copper veins were exhausted and the miners left for work out west. The year was 1988, but at Snow’s it seemed more like 1958. The sagging building, the forlorn signage, the old auto repair equipment, and the two elderly mechanics in dreary, oil-stained uniforms all recalled an earlier time. While I waited for the insurance adjuster to arrive and estimate the cost of repairs, I struck up a conversation with one of the mechanics.

“Say, can you tell me where the old Italian Hall is located?” I asked.

“The Italian Hall?” he responded.

“Yes, I’m sure it’s here. This is Calumet, right?”

“That’s right. This is Calumet.”

“Well, I’m just wondering where the Italian Hall is located. I’d like to see it.”

The mechanic raised his arm and pointed his work-worn index finger toward the window, in the direction of a large empty lot across the street. “That’s where it was. They tore it down last year. I guess you’re too late.”

Woody Guthrie appealed to KFVD radio listeners in Southern California and found a new audience among political activists, union organizers, and progressive writers who had never seen a bona fide Okie with left-wing politics. He cultivated his persona in songs, newspaper articles, and Bound for Glory. Even as he branched out into new areas, such as children’s song, Jewish songs, and novels and cartoons, the Okie persona never left him.

Wolff contrasts this with Bobby Zimmerman’s constant reinventions of himself. First the artist who would be Dylan abandoned his early interests in rock and blues for the emerging folk scene and changed his last name. Then, after discovering some Guthrie records from one of his folkie friends in the Dinkytown section of Minneapolis, he immersed himself in the Guthrie persona. He learned all of Guthrie’s songs and limited his performances at coffee houses and parties to the man’s repertoire. He mimicked Guthrie’s guitar style, speech patterns, and clothing. He carefully read Bound for Glory and began to create tall tales about his background, claiming that he was from Albuquerque or Gallup or Illinois — anywhere but Hibbing, Minnesota. “Dylan made himself authentic,” writes Wolff.

He changed who he was to get closer to the truth. Or try to. The sound that eventually came over pop radio — his timed drawl, the rural edge, the off-center sense of humor — was a lot Guthrie. That’s how Dylan became an original — through imitation. It’s as if he ran from his middle-class, mid-20th-century Hibbing and went back to Guthrie’s ’30s. Or as he put it, “I was making my own depression.”

Veteran folkies from the Dinkytown scene who were familiar with Guthrie chided Dylan for going too far with his impersonation. So Dylan went east to find Guthrie, claiming that he hopped freight trains and hitchhiked like Woody, when he actually got a ride from a friend. Dylan’s visits with a dying man in Greystone Hospital have been treated elsewhere, but Wolff captures an important element of this encounter. While Dylan was performing Guthrie’s songs for his idol, who was no longer able to speak, he confronted the reality that Guthrie was effectively gone, that his world of the Depression and his war against fascism had disappeared, that his fervent political dreams had vanished in the wind. Later Dylan would write:

Woody Guthrie was my last idol

he was the last idol because

he was the first idol

I’d ever met

that taught me

face t’ face

that men are men

shatterin’ even himself

as an idol …

Dylan’s confrontation with Guthrie’s demise was the starting point for Dylan’s composition of “Song to Woody,” written only a few days after their first meeting.

The song draws heavily upon Guthrie, using, almost note by note, the haunting, dirge-like melody of “1913 Massacre,” and opening with the line, “Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song,” which is derived from a similar opening Guthrie had used in a poem for Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. The song is a tribute but also a farewell. The lyrics set up comparisons between the Depression-era ’30s and the ’60s, between Guthrie’s old life and Dylan’s new life. “Listen to the song Dylan felt he needed to sing,” writes Wolff, “and you hear a kid who’s come a thousand miles only to discover that what he came for no longer exists.” The song is important for another reason: it marks the commencement of Bob Dylan, the singer-songwriter. Dylan’s first self-titled album included only two original songs — “Talkin’ New York,” a hillbilly’s satirical romp through the big city, and “Song to Woody.” Subsequent Dylan albums contained exclusively Dylan compositions.

Wolff may be right in locating the end of young Dylan’s idolization of Guthrie in “Song to Woody,” but the older folky continued to influence the younger artist. The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and The Times They Are a-Changin’ featured songs with powerful but artful political themes. While hardline politicos in the folk scene complained that Dylan’s songs about old girlfriends meant that he was turning his back on the struggle, those who listened closely to “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” and “The Times They are a-Changin’,” heard Dylan developing on the Guthrie tradition. Still, Dylan was carefully moving away from strictly political themes. Wolff quotes excerpts from a “letter back to Dinkytown,” which Dylan wrote for the 1963 Newport Folk Festival program, in which the artists refuses to answer the standard union organizing question posed in the powerful song written by Florence Patton Reece, “Which Side Are You On?”:

Hey man — I’m sorry —

…

the songs we used t sing an play

the songs written fifty years ago

the dirt farm songs — the dust bowl songs

the depression songs …

Woody’s songs …

when there was a strike there’s only two kind of views

… thru the union’s yes or thru the boss’s eyes

… them two simple sides that was so easy t tell apart

[have become]

A COMPLICATED CIRCLE.

The folk songs showed me the way

an I got nothing but homage an holy thinkin’ for the ol songs and stories

singin an writin what’s on my own mind …

not by no kind of side

not by no kind a category.

Dylan was preparing to reinvent himself again and he was not taking sides.

I turned to the mechanic at Snow’s and asked, “Where are the bricks?”

“What bricks?

“Well, the Italian Hall was made of bricks and they demolished it. So, what did they do with the bricks?”

“They hauled them away.”

“Yeah, but where did they go?”

“You want to know where the brinks are now?”

“Yes, where did they dump the bricks? Do you know?”

“Well, I don’t know why you want to know, but yeah, I know where they dumped them, sure.” He pointed out the window again. “Okay, go north for two stop lights. Then turn left and go until you get to the railroad tracks. Cross the tracks and take the first turn to the left. Keep going about a quarter mile until you see an island of poplar trees on the left. Then take the dirt road on the right for, I don’t know, a hundred yards or so. You’ll see a pile of bricks. If that’s what you’re looking for, that’s where you will find them.”

About a year later I was asked to perform in a Labor Concert in Kenosha, Wisconsin, along with Woody’s son, Arlo. I told Arlo I had learned the song “1913 Massacre” from his recording and that I wanted to give him a brick from the Italian Hall — a reminder of how our past can reemerge from under the weight of obfuscation.

Like the miners of Red Jacket, Michigan, who extracted copper from deep below the surface of the earth, Wolff helps us recover the truth about a tragic episode in our history.

¤

Darryl Holter is a historian, entrepreneur, musician, and owner of an independent bookstore. He has taught history at the University of Wisconsin and UCLA and is an adjunct professor at USC.

The post “I’ll Take You to a Place Called Italian Hall”: On Daniel Wolff’s “Grown-Up Anger” and the Calumet Massacre of 1913 appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2yvkoPA

0 notes

Video

youtube

Fourth-generation old-time fiddler and button accordion player Dwight “Red” Lamb is a master of Danish fiddle and accordion traditions, as well as Missouri Valley old-time fiddling. With more than 60 years’ commitment to collection, recording, preservation, and teaching, Lamb has mentored generations of regional and international musicians and is the 2017 recipient of the Bess Lomax Hawes National Heritage Fellowship.

0 notes

Video

youtube

watch the 18 minute doc here: pizza pizza daddy o

21 notes

·

View notes