#BkMConservation

Photo

Can you help us pinpoint which animal this hide belongs to?

This papier-mâché mask is a recent acquisition, likely originating from Korea. With its four “golden” eyes, this mask likely represents a Bangsangssi character.

Our conservators have identified the methods of construction, but we are still working to identify which animal the damaged skin, which adorns the piece, came from. In the Conservation Lab, we have studied the skin morphology and narrowed down some possible candidates, including: tanuki, golden jackal, binturong, corsac fox, wolverine, or mongolian wolf. But it has been difficult to assess due to insect damage.

We also examined guard hairs from the skin under the microscope. The thick hairs vary in color, have an undulating shape and are roughly 3.98 ± 1.33 cm in length. The cuticle of the guard hair has a flattened distal-scale pattern. The pigment bodies are dispersed throughout the cortex. The medulla is irregularly vacuolated. The thick shield of the root bulb is spade-shaped and larger than the shaft.

If you or someone you know might have ideas for what animal this hide and hair might have belonged to, please drop your theories and reasoning in the comments below until May 23!

#Brooklyn Museum#BkMConservation#art#mask#Korea#korean art#bkmasianart#science#animal skin#animal hide

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

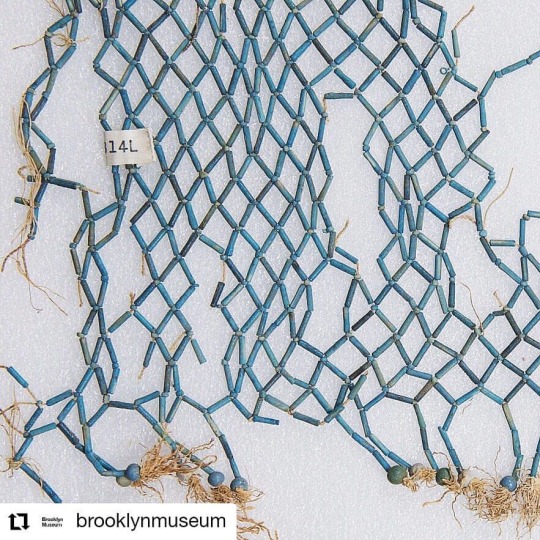

#Repost @brooklynmuseum شبكة القيشاني المصرية القديمة المصنوعة من الخرز #bkmconservation examines the materials and manufacturing of this ancient Egyptian beaded faience net . More at bit.ly/bkmconservation https://www.instagram.com/p/CA9mj2MhdLd/?igshid=pyv2qpplqk9x

0 notes

Photo

The only approach to the Mut Precinct is along the avenue of rams built by Nectanebo II (362-343 BC), the last native Egyptian pharaoh. The sandstone paving is original, even if somewhat worn and broken. Pretty amazing when you consider that it is about 2,400 years old.

As he promised, Abdel Aziz has been sending us regular updates on the column restoration project. By February 21, the work on the east column was in its final stages. As you can see here, the semi-final coating, toned to match the sandstone, has been applied. The herringbone pattern of grooves is to allow the final coat to adhere. A worker, wearing the protective gear, is using a grinder to smooth the surface of the lower column drums cut by Sayyid. The lowest column drums of most columns curved out from the column base, mimicking plants. The worker is grinding the new stone to match the ancient shape.

By February 27, the east column was finished. This is the better-preserved east side of the column.

The other side of the column was in worse condition and essentially had to be rebuilt. The missing parts have been filled in so that it is now complete and stable. Originally there were thin walls between the columns (called “intercolumnar walls”), their junction with the columns marked by a projection on the lowest column drums. The restorers have mimicked this feature on the restored column. Talk about attention to detail.

In our last post on-site, the base of the west column had just been cleared of the deteriorated sandstone. By February 21, a new base had been constructed and one of the restorers was creating a new support for the column drums using baked brick and a cement mixture. We used a similar method to create new bases for the smaller columns in Temple A that we restored in 2019.

It takes time for the cement to cure properly, but by February 27 the two ancient column drums had been mounted on the new column base and the scaffold had been set up, ready to lift the remaining drums into place. Stay tuned for the final installment.

One big attraction for tourists is a dawn balloon ride over the monuments on the west bank: Deir el Bahari, the Valley of the Kings, the Ramesseum and Medinet Habu. We saw as many as 21 balloons at a time this year.

Posted by Richard Fazzini and Mary McKercher

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#bkmconservation#Egypt#BkMMutDig#Mut#temple#excavation#BkMEgyptianArt#archaeology#column#MutDig

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This work by French sculptor François Rude is a ceramic maquette, or scale model, of a sculptural decoration for the Arc de Triomphe, a commission awarded to Rude by the French government in 1833. The final sculpture, Départ des volontaires de 1792 (Departure of the Volunteers of 1792), also known as La Marseillaise, decorates the right pillar on the front of the Arc de Triomphe and is nearly 42 ½ feet tall. It depicts men in classical-style armor, led by a winged female warrior figure. This is a stylized rendering of a real historical event, the Battle of Valmy, where a French citizen army was victorious against Prussian and Austrian forces early in the Revolutionary Wars after the French Revolution.

This maquette is considerably smaller at only 27 ½ inches tall, but what it lacks in size it makes up for in sheer dynamism. The hand of the artist is visible in the roughly modeled surface and the abundant tool and finger marks. Though the figures are not carefully finished, they nevertheless seem alive, in fluid motion. The variegated colors and many inclusions and imperfections in the ceramic body hint to Rude using a lower quality clay which may never have meant to have been fired; sculptors often use clay to work out their thoughts before recycling it to craft the next iteration of their ideas. For whatever reason, however, this piece of sculpting was deemed important enough to be saved by firing it. The many cracks in the piece may have occurred during the firing process due to the impurities in the clay.

Above: detail of rightmost figure, showing toolmarks and fingerprints in the clay

Before conservation could begin on the sculpture, it had to be assessed to determine what prior treatment it had undergone. Thankfully, in this case, we have records of its treatment in 1984, as well as notes from former Brooklyn Museum conservator Jane Carpenter upon its acquisition by the Brooklyn Museum in 1989. Some time before 1984, both of the female figure’s hands had broken off and were lost, as were the proper right hands of two of the male figures. The work had suffered severe damage in the form of a horizontal break across the entire sculpture at the female figure’s waist, and was repaired (along with other cracks and breaks) with tinted plaster, which also covered the entire back surface. Finally, the entire front surface was coated with reddish-brown pigment. In 1984, the plaster and reddish-brown pigment was (mostly) removed, and the back was reinforced with four aluminum brackets adhered with epoxy and cotton tape. Losses along the horizontal break were filled in and inpainted with gouache.

Above: the back side of the maquette before treatment

There were many spots of plaster and reddish-brown pigment that remained from the previous treatments, and there was also something oddly flat and one-dimensional about the color, too. Typically, a conservator will cover as little of the object’s surface as possible when inpainting fill material to match the surrounding area; in this case, it was found that almost the entire surface was coated with gouache! This may have been done to unify the repair work and create a more homogeneous appearance, as the gouache obscured the mottled coloring of the clay. However, this is an important feature in understanding the complicated history of this sculpture as well as its status as a “process object” created as part of a larger work. Though it is unclear what the “original” surface of the maquette may have looked like at the time of its creation, it was determined that removal of the gouache to reveal the current surface was preferable.

Above: removal of gouache with a swab, revealing ceramic surface underneath

Since gouache is soluble in water, cleaning the surface of the maquette was simple yet time-consuming. Small cotton swabs were hand-made, dampened, and carefully rolled across the surface. Along with the gouache, more of the old reddish-brown pigment was removed, though traces still remain in the many crevices. In total, wet cleaning the sculpture took over fifteen hours of work.

Above: before (left) and after (right) inpainting a filled crack

Instead of completely removing and redoing the old fills, which were made of a cellulose-based filler that appeared perfectly stable, they were shaped and resurfaced using an acrylic-based modern product to help them more effectively blend texturally into the surrounding area. Finally, since the color of the fills didn’t perfectly match the ceramic, they were aesthetically integrated with watercolor and gouache (applied only over the fills and not the entire surface!). These materials are easily soluble in water so the piece can be re-treated in the future if necessary. Now, instead of obscuring the complex and interesting surface of the maquette, it can be more fully appreciated as an object that gives unique and intimate insight into a great sculptor’s working processes.

Below: the maquette after treatment

Written by Celeste Mahoney, Assistant Objects Conservator

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#conservation#art conservation#BkMConservation#sculpture#francoise rude#maquette#Arc de Triomphe

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Summer as a Conservation Intern

I’m Carolina Benitez, and this summer I was the conservation intern at the Brooklyn Museum. As a pre-program intern, getting experience in the field can be particularly difficult, and it’s hard to decide which specialty you’re most interested in without having the proper experience first. Working at one of the oldest conservation labs in the US was an incredible experience, and having an open lab meant that conservators working in different specialties work within the same space, making collaboration within the department more feasible.

Through the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Opportunity for Diversity in Conservation Program, I was able to be placed to work at the Brooklyn Museum to properly develop my skills through a variety of projects under several supervisors.

Under the direction of our head of conservation Lisa Bruno, I worked in Objects Conservation with project conservator Celeste Mahoney in order to treat 18th century Rajasthani sandstone balcony pieces to ensure their preparation for our fall exhibition. Removing mortar and inpainting these pieces was incredibly fun, and gave me the opportunity to utilize and develop my skills in manual dexterity and color theory.

In Paintings Conservation, we worked with Mellon Fellow Isaac Messina to create a database of paint swatches from the lab’s pigment collection in order to create a record for further research through technical photography and multiband imaging. I learned how to make paint with deionized water and rabbit skin glue and got to help with photography to learn more about properties within certain pigments.

For my favorite project this summer, I got to examine and carry out treatment of a gelatin silver photograph; a portrait of sculptor William Edmonson by the photographer Consuelo Kanaga. With Associate Paper Conservator Elyse Driscoll, I was able to treat the photograph’s cracked surface with 1% photo grade gelatin. Afterwards, I conducted a dry cleaning of smudging on the surface of the mount with a kneaded eraser, a vinyl eraser, and vinyl eraser crumbs. Finally, I was able to work on the back of the mount in order to remove residual linen tape with 4% methyl cellulose as a poultice.

The most rewarding part of these projects is getting to have a direct hand in preserving important pieces of art history. As an art historian and a museum lover, I feel that learning and seeing objects and artworks can be fulfilling in itself. The most rewarding aspect of this career is knowing that your preservation ensures the protection of history and knowledge for future generations. After my internship, I can say that my experience at the Brooklyn Museum exceeded my expectations, and I am more adequately prepared for my next chapter.

Posted by Carolina Benitez, Conservation Intern

#brooklyn museum#bkmeducation#internship#new york city#nyc#brooklyn#museum#intern#art#conservation#bkmconservation

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

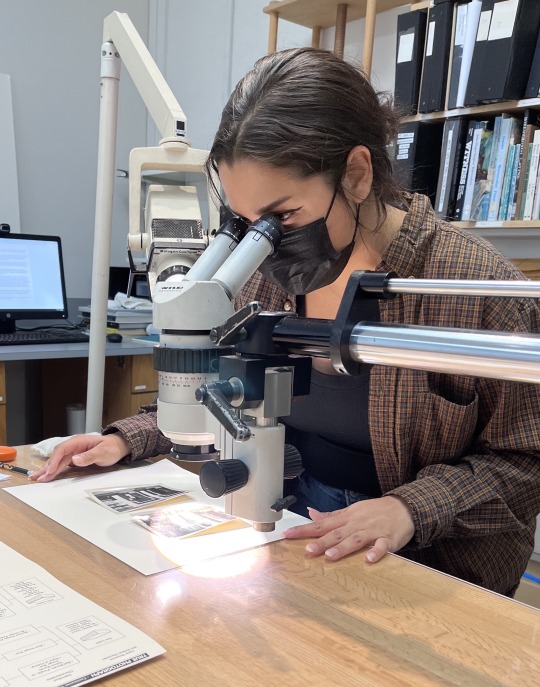

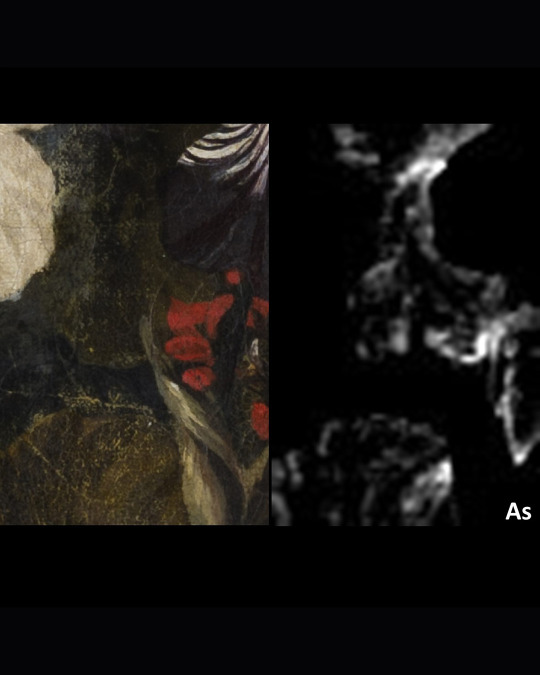

Meanwhile in the Conservation Lab at the Brooklyn Museum… 🌼🔬

The Brooklyn Museum paintings conservators welcomed scientists from the Met’s the Network Initiative for Conservation Science (NICS) to assist with a long-term treatment of a work in the Brooklyn Museum's collection by Mary Moser, a celebrated 18th century artist and one of the only two female founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

Over the course of two and a half days, we analyzed the pigments used by Moser in this painting using a portable X-ray fluorescence scanning system, which allows us to visualize the distribution of chemical elements on an artwork surface without the need to remove a sample. Here you can see the set-up for this scanning process as well as the distribution of arsenic in a yellow flower from the still life painting, which likely indicates the use of the arsenic-based pigment orpiment.

🖼️ Mary Moser (English, 1744-1819). Vase of Flowers, ca. 1780. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Daniel L. Silberberg, 64.92.5 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum). → Courtesy of Ellen Nigro → Elemental map courtesy of NICS

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#Mary Moser#BkMEuropeanArt#painting#bkmconservation#art conservation#conservation#painting conservation#TheDailyNICS#Royal Academy of Arts

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

November 4th is #AskAConservator Day! Conservators around the world will be answering questions about their work in the spirit of sharing knowledge and celebrating the growth of the field, and our #BKMConservation staff would love to hear from you. Our conservation lab is made up of ten conservators, four interns working across paper, painting, and object conservation as well as four Collection Management staff. Our conservators worked on approximately 840 objects and artworks this year while our Collections Management team has worked on multiple large, long-term storage/rehousing projects across all our collections.

Have a question for any of them? Look out for our post and Instagram stories on November 4th. The lab will be answering questions from 9am-5pm EST.

Photos by Maribel Vitagliani and Cindy Ortiz

#askaconservator#art conservation#bkmconservation#conservators#art#museums#paper conservation#painting conservation#object conservation#collection management#objects#artworks#storage#rehousing

277 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In just two short weeks, Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive opens debuting eleven new artworks, in conversation with key works made by the Brooklyn artist since 2017. For several of these works, Khan collaborated with museum conservator Victoria Schussler and curator Ayşin Yoltar-Yıldırım to stage intercessions with objects from our Arts of Islamic World collection. The series’s title “Law of Antiquities” refers to relatively recent global regulations that safeguard cultural objects—such as the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict—but do not afford individuals and communities that same protection. It also refers to guidelines prescribed by Brooklyn Museum conservators for interacting with the artworks, around which Khan constructed the project’s rules of engagement.

See this series and more on October 1, when Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive opens, presented as part of the UOVO Prize for an emerging Brooklyn artist.

Photos by Willa Cosinuke, Sarah DeSantis, and Carmen Hermo

#Baseera Khan#Uovoprize#Uovo#Brooklyn Museum#Uovo Prize#Law of Antiquities#global#regulations#bkmartsofislamicworld#arts of the islamic world#islamic art#conservator#bkmconservation#artist#art#brooklyn#nyc#exhibitions

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Baseera Khan’s Law of Antiquities series, on view in I Am an Archive, the artist’s hands often approach and mimic the positioning of the museum conservator’s hands. While this safeguards the fragile surfaces of these historic collection objects, it also alludes to the way that museum procedures disallow touch and proximity in objects that were very much used and functional, such as the 13th-cenury candle stand (from present-day Iran or Central Asia) and late 19th-century earrings and headdress (from Tafraout, Morocco) pictured here.

Khan designed a set of nitrile gloves, used to protect art objects, for the Law of Antiquities photoshoot. The bespoke gloves layer varied colors, and include collaged black-and-white images of a textile in the collection that was too fragile to be included in the shoot. As Brooklyn Museum conservator Victoria Schussler handled the objects, she wore Khan’s creations.

Behind-the-scenes process photos by Willa Cosinuke, Sarah DeSantis, and Carmen Hermo

#Baseera Khan#Law of Antiquities#contemporaray art#contemporary artist#brooklyn museum#bkmconservation#candle stand#headdress#earings#gloves#bespoke#conservator#conservation#art#artist

16 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

So much happens behind-the-scenes of a Museum, and even more so within a conservation lab. Tune in to our latest video with Lisa Bruno, Carol Lee Shen Chief Conservator, for peek into how we care for our collections—from reversing outdated treatments to stories behind recent projects and what took place when the Museum shut down due to COVID-19.

Video by Anne Sofie Nørskov, Joanne Leonhardt Cassullo Video Fellow Treatments featured: William Williams, Deborah Hall (1766) ⇨ Cecily Brown (British, born 1969). Triumph of the Vanities II, 2018. Purchase gift of John and Barbara Vogelstein in honor of Anne Pasternak © artist or artist's estate ⇨ Assyrian reliefs, Neo-Assyrian Period, reign of Ashur-nasir-pal II, circa 883–859 B.C.E. Funding for the conservation of the Assyrian Reliefs was generously provided through a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project.

#AYearattheMuseum#A Year at the Museum#bkmconservation#conservation#art conservation#art#science#collection care#direct care#treatments#art conservators#museums#art museums

98 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Conservators Ellen Nigro, Natalya Swanson, and Kate Wight Tyler discuss the use of repurposed and recycled materials in artwork and the overlap between Environmental and Art Conservation in this conversation inspired by Earth Day.

KWT: As themes like consumption and climate change are increasingly addressed by artists, we see more use of recycled, reclaimed, discarded, and degradable materials in their work. How has this evolved our role as conservators?

NS: Sustainability-themed art is challenging conservators to adapt our practices, partially because repurposed, reclaimed, and recycled materials tend to be more fragile and often require innovative solutions to preserve signs of use, and partially because it raises bigger concerns about the sustainability of our materials and practices.

El Anatsui’s fabric-like metal tapestries made of recycled liquor-bottle caps and wrappers present interesting challenges. Every time the artwork is installed it is formed into a new shape. Variability is a defining feature of these works, but also requires a lot of handling which wears on the recycled metal tabs. Our conservation strategy includes attaching mesh onto the back of the artwork, which redistributes the weight off the metal tabs without restricting future iterations of the artwork. By using recycled materials and employing local community members to help construct the tapestries, El Anatsui not only comments on consumption and waste practices, but literalizes a foundational sustainability principle of prioritizing community well-being when making decisions. The more I work on this project, the more I wonder how conservators can embed sustainability values into our practices.

EN: The artwork cycle by Hugo McCloud is a collage made of single-use plastic bags adhered to a plywood panel. As a paintings conservator, working with the McCloud has been a different project than what I am used to, since there isn’t any paint used in the artwork. It was an opportunity to collaborate with my colleagues in objects conservation, especially Kate Wight Tyler. Although my education included lessons on plastics and plastic degradation, I haven’t thought about them in a while! Having conversations with Kate really helped me understand the degradation that may happen in this work.

KWT: When components creating an artwork are made for different purposes or already had a use-life it can complicate the terms of preservation. How does caring for these works reiterate and/or contradict the message the artist is trying to achieve?

EN: Cycle is part of a series where McCloud depicts workers in developing countries moving large amounts of materials, often in plastic bags. These works address class, labor, resources, and how they are all intertwined on a global scale. They call attention to the prevalence of plastic in our lives and throughout trade systems.

In this work, as well as others in the series, McCloud uses new bags and plastic sheeting in these works instead of upcycling materials. By doing this, I think he reiterates and highlights the message that plastic is present in many aspects of our lives and throughout global trade. It seems that McCloud wants to make an environmentalist statement by calling attention to the pervasiveness of plastic in the world, but by using new plastic, he is actively participating in the use of single-use materials and contradicting the environmentalist message.

Caring for this work of art involves gathering information from the artist through a questionnaire or an interview to learn about how he views degradation in his work. As conservators, we are trained to decrease the chance of physical change in an object, however, this is not always the best approach for treating works by artists that value degradation or change in the work’s aesthetic over time. We are still in the process of gathering this information. For example, if Hugo McCloud prefers for his work to remain as pristine as possible, we may implement preventive conservation measures like glazing to protect the surface from light, humidity, dust, and other pollutants. However, if he values degradation of the plastic, then we may take a more passive approach to the care of this work.

NS: I’ve been thinking about the question of artist intent in regards to the El Anatsui a lot, and wonder to what extent his emphasis on intersectional environmentalism (a term used synonymously with “sustainability” that only differs in the sense that it underscores the intersectional nature of sustainability work, rather than relegating it to the environmental sector) should affect our decisions as conservators.

Unlike the McCloud piece, El Anatsui’s Black Box embodies sustainable decision making in all aspects, from sourcing recycled materials to employing locals to create the works. Because of this, I’ve been feeling conflicted about our decision to use plastic mesh in our conservation treatment. Like all decisions, the rationale behind our choice was complicated: we needed to use a flexible but strong material that won’t change the physical properties of the artwork; we also wanted to use something that has a long lifetime, so we won’t have to redo the treatment in a few years. The plastic mesh meets all these criteria, but conflicts with the message El Anatsui communicates by making these works.

When conserving conceptual art, conservators sometimes have to make compromises with physical elements to ensure they are preserving what’s important (the concept). It feels like we are grappling with a similar type of problem with sustainability-themed artworks.

KWT: Art Conservation is sometimes confused with Environmental Conservation. In what ways are they connected and how do they differ?

NS: This is a challenging question. Both heritage and environmental conservation are based on the fundamental belief in caring for valued and shared heritage. Both fields are scientifically-oriented professions that use a similar technical language - and although we both use terms like “restoration,” “preservation,” and “conservation,” we mean very different things when we use these terms! Also, both professions believe in and practice collaborative interdisciplinary work.

Perhaps one reason why there are not more overlaps is because our guiding principles are significantly different: environmental conservationists believe in a holistic approach to community well-being achieved through balancing future and present needs; art conservation is primarily concerned with the long-term preservation of cultural property. Sustainability work has shifted away from an expert-driven decision making model, while this is still the dominant approach in heritage conservation. Over the past few years, the boundaries between our profession have gotten more blurry as heritage conservators realize that preservation of the natural environment is critical to long-term care of tangible heritage. We’re still working on how to integrate this thinking into our “best practices,” but there’s widespread agreement that we can begin by creating more space for collaborations and candid dialogue with our environmental conservation colleagues.

EN: As I have worked on the McCloud, I’ve been struck by the difference in how conservators think about plastic degradation versus how environmentalists view it. While the two fields agree on the science of plastic degradation, what is perceived as acceptable or unacceptable is quite different. In the context of art conservation, plastic is a very delicate material and one that easily degrades through exposure to ambient light, humidity, and temperature, and something that may start to change in a relatively short period of time, affecting the function and/or aesthetic of a collection object. However, environmentalists express concern over the timeline of plastic degradation, and highlight that the plastic may not fully decompose for hundreds of years. The two fields have very different ideas about what timeline for degradation is acceptable.

Photos of El Anatsui (Ghanaian, born 1944). Black Block, 2010. Aluminum and copper wire, two pieces. Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of William K. Jacobs, Jr., by exchange, 2013.7a-b. © artist or artist's estate and Hugo McCloud (American, born 1980) cycle, 2020.

#bkmconservation#earth day#hugo mcloud#el anatsui#sculpture#material#resuse#preservation#conservation#environmental conservation#art conservation#environmental#repurporsed#recycled

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today is #AskAConservator Day! To celebrate the growth of the field, our #BkMConservation staff will be answering your questions today from 9am-5pm EST.

The BkM Conservation lab is one of the oldest in the country, starting in 1934 by two pioneer paintings conservators, Sheldon and Caroline Keck. Since then, our lab has expanded and is made up of ten conservators, four interns working across paper, painting, and object conservation as well as four Collection Management staff. Our conservators worked on approximately 840 objects and artworks this year while our Collections Management team has worked on multiple large, long-term storage/rehousing projects across all our collections. Have a question for any of them? Leave it for them here!

Photo by Walter Andersons

#askaconservator#ask a conservator day#art conservation#bkmconservation#art conservators#collection care#museum careers

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In preparation for its display in Jeffrey Gibson: When Fire Is Applied to a Stone It Cracks at Brooklyn Museum, the bronze relief of Charles Rumsey’s Study for Buffalo Hunt needed to be cleaned. It had previously been displayed for years outdoors. It was covered in a thick layer of wax and resin applied over decades as protection. The coatings had turned brown and absorbed dirt. Wax and resin were no longer necessary since they were not original and the object would be indoors. However, the coatings had become impossible to remove except with extremely harsh chemicals like paint stripper. Using a special laser, however, it was possible to remove this coating without dangerous solvents. The old, dark coating is on the left, the cleaned surface on the right.

Posted by Harry DeBauche

#bkmconservation#jeffreygibsonbkm#charles rumsey#clearning#art#science#art conservation#laser#solvents#resin#wax#art museums

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In preparation for reopening, KAWS’ Along the Way, was reinstalled in the lobby. The two massive, wooden figures are made from blocks of Brazilian walnut. Years of display had caused the wood to fade slightly. Aisha De Avila-Shin and Harry DeBauche reapplied an oil and varnish following the artist’s instructions, restoring the objects’ rich color and gloss.

Posted by Harry DeBauche

KAWS (American, born 1974). ALONG THE WAY, 2013. Wood, 216 × 176 × 120 in. (548.6 × 447 × 304.8 cm) overall. Brooklyn Museum; Gift in honor of Arnold Lehman, TL2015.27a–b. © KAWS, courtesy of the Mary Boone Gallery.

#bkmconservation#kaws#brooklyn museum#brooklyn#art#artist#sculpture#companions#installation#art handlers#art conservation#wood

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"William William’s portrait of Deborah Hall is a constant presence in the Conservation Lab while she is undergoing conservation treatment. This painting was purchased at auction by the Brooklyn Museum in the 1940s, and at that time, it was in dire condition. Upon its arrival at the Museum, our Lab’s founding conservator, Sheldon Keck, stabilized the flaking paint and carefully reintegrated the many losses, ensuring Deborah’s portrait would last into the future. Although we cannot continue the current treatment of this painting while we are working from home, I appreciate the time I have to reflect on how precious this artwork is, and how fortunate we are that it has lasted for over 250 years. It reminds me that paintings can be like humans—they are not only delicate and sensitive to their environments, but also surprisingly resilient in difficult times. The treatment and research of this painting is an energizing group effort. One of the best aspects is collaborating with the other paintings conservators at the Museum, and our Assistant American Art Curator, Margarita Karasoulas, as well as our incredible colleagues from Winterthur Museum, Yale University Art Gallery, and Eskenazi Museum of Art at IU. This is all made possible by a Conserving Canvas grant through the Getty Foundation. The conservation and research of this precious painting is a daily joy, and I can’t wait to get back to it!"

Posted by Ellen Nigro, Mellon Fellow, Paintings Conservation

William Williams (American, 1727-1791, active in America 1746-1776). Deborah Hall, 1766. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, 42.45 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

#artforthesociallydistanced#brooklyn museum#museums#coronavirus#social distancing#conservingcanvas#bkmconservation#art conservation#portraiture

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sometimes an artist forgets to sign their artwork. Seems crazy, but it happens a lot. For example, this oil painting by acclaimed 19th-century artist John Singer Sargent is unsigned.

When a painting comes to the collection unsigned, and the artist is living, we can give them an opportunity to sign their work. This recently happened with two pieces added to the collection.

Paintings Conservators Josh Summer and Lauren Bradley with the artist, Constance P. Beaty

Constance P. Beaty the artist who painted this portrait, a gift of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg came to the Conservation lab to sign it just before its recent installation in the American Galleries.

Fred Brathwaite aka Fab 5 Freddy created this work Jack Johnson: I Beat The Great White Hope in 2016 . It was a gift of Sugar Hill Capital Partners in 2017. Upon examination, we realized the painting was unsigned. Fab 5 Freddy recently came in to sign his painting, and being the great showman he is, we couldn’t resist filming it.

youtube

You can see more of Fab 5 Freddy on BBC 2 – A Fresh Guide to Florence with Fab 5 Freddy where he addresses themes similar to those in our recent exhibition One: Titus Kaphar.

Posted by Lisa Bruno

#bkmconservation#brooklyn museum#conservatory#artists#signature#art conservation#fab 5 freddy#brooklyn#museums#art museums#fab five freddy#Fred Brathwaite#Ruth Bader Ginsburg#jack johnson#john singer sargent

280 notes

·

View notes