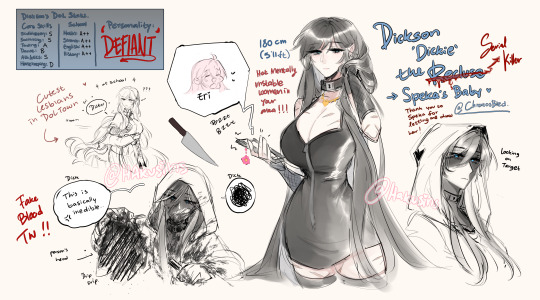

#Dickson the Recluse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Friend's PC sheet + honorable close ups. Dick belongs to @chronosbled (Speka)

Dickson the Recluse (the Serial Killer)

Thank you so much to my dear friend for not only joining me in my struggles in DOL but also adding her adorable child into it!! This is a PC sheet to get everyone introduced to the wonderful (deranged) sweetheart known as Dick, short for Dickson! I'll let my friend do the rest of the introduction~! But Eri is very excited to show off her new (toxic, deranged, abusive, possessive) girlfriend~!

#THANK YOU TO SPEKA FOR LETTING ME HAVE FUN AND DRAW HER PC SHEET FOR HER#UWAUWHUHAUHAHA IM SO EXCITED MY OLD FRIEND HAS GOTTEN INTO DOL AND WE'VE ALREADY PLOTTED SO MUCH OVER IT#OOOHHUGIUIHIUGH IM NOT SHUTTING ABOUT THIS MFER PLEASE EVERYONE LOOK AT THIS BEAUTIFUL CHILD#dol#dol related#degrees of lewdity#dol pc#dickson the recluse#dickson the serial killer#fan art#art#mine#my fan art#my art#chronosbled#AGAIN THANK YOU TO SPEKA!!!!!!!#I CANT WAIT TO POST THE REST OF THE STUFF WE'VE ALREADY DISCUSSED

57 notes

·

View notes

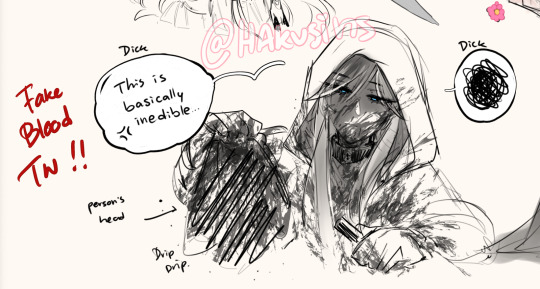

Text

Not Quite by the Book: A Novel Family Life Fiction/Women's Domestic Life Fiction/Contemporary Romance Setting - Massachusetts Publisher : Lake Union Publishing (March 1, 2025) Paperback : 317 pages ISBN-10 : 1662523467 ISBN-13 : 978-1662523465 Kindle ASIN : B0D4R9C5S5 A bookstore owner discovers that life as a recluse isn’t for everyone in this sharp yet sweet novel about how sometimes you need to abandon the quest for love to find your true passion. Emma Rini is in a rut so deep she could shelve books there. While her sister awaits her first baby, and her parents kick off retirement with vow renewals and travel, Emma stays put among the stacks of the family bookshop. In fact, she can’t remember the last time she took a vacation. Or had a romance that hovered above disappointing. When her parents assume she’ll take over the shop for them without a break, she realizes she needs to get away—back to the nineteenth century. Channeling her favorite poet recluse, Emily Dickinson, Emma rents a crumbling manor house outside Amherst where she can learn how to be quietly, blissfully alone. But becoming a world-weary spinster isn’t easy. She can’t start a fire or reason with the bunnies that are destroying the garden. She finds herself sparring constantly with the grumpy-hot architect who is renovating the manor. And then there’s the secret admirer who keeps sending her complicated floral messages… No matter what she does, the outside world keeps knocking, and Emma starts to dream about the future. Will she forgo love for the family legacy? And will she shrink away or become the sort of bold person fortune favors? Dollycas's Thoughts Emma Rini has been left to run the family bookstore while her sister and her husband get ready for the birth of the first child and her parents celebrate another vow renewal and travel while planning to retire from the bookshop soon. These changes won't change anything for Emma because her entire life has been the bookstore. No vacations, no romantic relationships, just shelving and selling books. After she sees her family all having fun without her and assumes she will keep the store going after their retirement Emma hits a breaking point. If she ever has a chance of any "me time", it is now. Emma's favorite poet is Emily Dickinson and she has the chance to stay in a deteriorating manor house in Amherst, Dickinson's hometown, and find her inner Emily. She quickly books a six-week stay. But living a reclusive life isn't as easy as she thought. The manor is cold and can't build a fire. She planted a garden but the rabbits decided it was planted as their lunch. The handyman's visits to help her are contentious. Plus she keeps receiving flowers with unsigned cards. Did she have a secret admirer? She finds herself pulled in several directions. She has some big decisions to make. Does she finally put herself first? or will she return to what she had hoped to leave behind? _____ I have read several of Emily Dickinson's poems over the years so the theme of this story made me excited to read this book. I immediately felt for Emma. Family businesses are hard when everyone is on the same page but horrendous when one person is left responsible for everything. Emma is just like I was, not wanting to make waves, so she holds everything in but I was still upset with her family for making assumptions and decisions and not including her in the conversations. The people she met in Amherst were interesting and felt true to life. She met several at a letter-writing class at the local bookstore and I love the whole idea of the class. Davis, first known as the "handyman" turned out to be her landlord and an architect with a plan to renovate the manor as soon as possible. He is also very easy on the eyes. Plus, he has an adorable dog. Emma tries so hard to do things Emily Dickson did but she does start to open up slowly. She is unsure about a lot of things, putting more pressure on herself every day. Davis also deals with pressure and strife within these pages. I had fun watching them grow right up to the final page. One mystery in the story was evident to me quickly but that didn't lessen my enjoyment of this story. Another was a mystery until it was revealed. Not Quite by the Book is a fun entertaining read. I was drawn in more with each chapter. The pacing was perfect. The world-building created great imagery and loved that the wi-fi was nonexistent in the manor. For me, it was A Perfect Escape. I voluntarily reviewed an Advance Reader Copy. This does not affect my opinion of the book or the content of my review. Thank you to Amazon for providing me with an ARC through their First Reads Program. Your Escape Into A Good Book Travel Agent About Julie Hatcher Julie Hatcher is an award-winning and bestselling author of mystery and romantic suspense. She’s published more than sixty novels since her debut in 2013 and currently writes series as herself, as well as under multiple pen names, for Lake Union Publishing, Harlequin, Kensington, Sourcebooks, and Crooked Lane Books. Julie is the 2022 Maggie Award Winner for romantic suspense, the 2020 Golden Quill Award Winner for Series Romance, a double finalist (and winner) of the 2020 National Readers Choice Award for Romance Adventure, a 2019 double-finalist (and winner) of the Daphne Du Maurier Award for Mystery & Suspense, the 2019 Stiletto Award for Romantic Suspense and the 2019 National Excellence in Romance Fiction Award for romantic suspense. She is a member of national Sisters in Crime, as well as a local board member, a member of Romance Writers of America, International Thriller Writers, Independent Book Publishers Association, Midwest Book Publishers Association, Mystery Writers of America, Women’s Fiction Writing Association, and Novelists Inc. She’s ghostwritten for NYT Bestselling authors and led classes and workshops for numerous writers conferences, libraries and groups on topics from plotting and outlining mysteries, to social media 101. Julie’s recently expanded her industry knowledge and experience by taking the self-publishing plunge. She founded Cozy Queen Publishing LLC in 2020 and coordinated her efforts with a team of professionals from her traditional writing world to launch a new cozy mystery series in September 2021, with 12 titles available now. When Julie's not creating new worlds or fostering the epic love of fictional characters, she can be found in Kent, Ohio, enjoying her blessed Midwestern life. And probably plotting murder with her shamelessly enabling friends. Today she hopes to make someone smile. One day she plans to change the world. Website Facebook Threads Instagram Julie Hatcher also writing as Julie Anne Lindsey, Jacqueline Frost, Bree Baker Disclosure of Material Connection: I received this book free from the publisher. I was not required to write a positive review. The opinions I have expressed are my own. Receiving a complimentary copy in no way reflected my review of this book. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” “As an Amazon Associate, I earn a commission from qualifying purchases.” I am also an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.” Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

George Harrison photographed on March 25, 1966; photo 1 by Nigel Dickson, photo 2 by Robert Whitaker.

“‘I asked to be successful,’ [George] said. ‘I never asked to be famous. I can tell you I got more famous than I wanted to be. I never intended to be the Big Cheese.’” - Evening Standard, 18 March 1966

“People used to say George was a recluse, but he would say: ‘well, I just don't go where you go,’ or ‘I don’t go where the press is, or to those sorts of places.’ We had a lot of friends and had quite a social life. You can put on this other persona and be low key about it. We never traveled with anybody, we just went on our own. George traveled on his own. The less attention you call to yourself the easier it is. That was his philosophy.” - Olivia Harrison, The Australian, March 3, 2005

“My dad was always, ‘Don’t be famous. Don’t envy this. Be a musician, but don’t be famous. You lose all your freedom and you can’t do anything. You have to live a different life.’ We were both private people, and he did a really great job of keeping me out of the press all my life.” - Dhani Harrison, New York Times Syndicate, March 15, 2013 (x)

#George Harrison#quote#quotes about George#quotes by George#1966#1960s#George and fame#The Beatles#George and Olivia#George and Dhani#fits queue like a glove

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflection

Shulk is probably the least person I’ve spent “lives” with. It isn’t because I dislike him but because Dickson and I melded together well. Zanza is, well, Zanza. Shulk did as promised; he shared the wealth he had stolen from Dickson and I about 100 years ago and we bought a secluded manager on the outskirts of colony 7, near the knee of the Bionis. As we first entered, Shulk dropped his belongings on the dusty square dining table left by the previous owners. It was musty, I’ll admit, but I had no complaints. We were promised 2 bedrooms, a common area and an outdoor watershed. The house itself has a nearby pond whose water comes from a cave system and quenches the thirst of the colony for some passerby. I place my belongings in the dusty bedroom.

“It seems quaint,” I say, inspecting the humble furniture and bare walls. There were even dishes, a range, and pots left behind. “Yes, but no running water,” he says and walks across the creaky floor. Shulk hasn’t changed much since we gained our immortality.

Despite being the youngest of about 5 years, he thought a lot about potential problems and plans. Living in that house with him was nice; he kept to himself and cleaned as necessary. The only glaring problem was his reclusiveness and desire to be alone; it never occurred to the colony folk that he and I cohabited. If I brought it up, of course, the first thought was “Oh, so you are the best of friends,” but such was the way with living with another man.

0 notes

Note

Oh my gosh, Rebekah Harkness had such a messy and sad life www(.)nytimes(.)com/1988/05/22/books/is-there-a-chic-way-to-go(.)html?pagewanted=all

Thanks for linking this article! I love reading about her… and yes, she did have a very unique and tragic life. I’d love to watch a documentary about her.

_______________________________________________________________________‘IS THERE A CHIC WAY TO GO?’A week after her death on June 17, 1982, the mortal remains of Rebekah Harkness were toted home by her older daughter Terry in a Gristede’s shopping bag. The ashes were placed in a $250,000 jeweled urn made by Salvador Dali. They didn’t fit: “Just a leg is in there, or maybe half of her head, and an arm,” said one of Rebekah’s friends. Several hours later, the top of the urn - called the Chalice of Life - was somehow, by unknown agencies, uncovered. “Oh, my God,” said a witness. “She’s escaped.”

This post-mortem mischief was going on at Harkness House, the East 75th Street town house headquarters of the Harkness Ballet Foundation, which Mrs. Harkness had modeled on the St. Petersburg Ballet School. The building, according to Craig Unger, the author of this rich-man/eye-of-the-needle biography, was in a state of putrefaction, “crumbling like Tara after the Civil War.” Meanwhile, in her apartment at the Carlyle Hotel, people who called themselves Rebekah Harkness’s friends were pillaging, “grabbing things right and left.”

Rebekah’s younger daughter Edith, a failed suicide who had spent many years in mental institutions, took only her mother’s pills: Seconal, Nembutal, Valium, Haldol, Librium and various painkillers - 40 vials in all. Allen Pierce, Rebekah’s son by the first of her four husbands, was unable to be present. Convicted of murder in the second degree, he was behind the bars of a Florida jail. Bobby Scevers, Rebekah’s lover, 25 years younger than she and a self-declared homosexual, pronounced her children “the most worthless, selfish, useless creatures I’ve ever seen.” (Mr. Scevers has a stunning way of placing himself squarely in the center of every sentence he utters; he appears to believe that Rebekah Harkness’s death happened more to him than to her.) If I report on the demise of the multimillionaire patron of the dance dry-eyed, it is because I am confident in the belief that nothing we say about the dead can prejudice the Defense or tip the Scales of Judgment. I myself wouldn’t give the time of day to anyone who cleaned her pool out with Dom Perignon, put mineral oil in the punch at her sister’s debutante ball and (all in the middle of the Great Depression) got tossed off an ocean liner for shouting obscenities, throwing dinner plates at an orchestra of Filipinos gamely playing the American national anthem, and offending the sensibilities of her fellow passengers by swimming nude - for which actions she counted herself witty. (I do admit, however, that I’d go a long way to read a sentence like this, spoken by Bertrand Castelli, the co-producer of “Hair,” about the time he made love to Rebekah Harkness in her office: “It was as if we were two camels in the desert who suddenly know that the only way to make an oasis is to really talk sense.” After his brief interlude in the oasis, Mr. Castelli was made the artistic director of the Harkness Ballet. “Kiss me,” she commanded. “The others, they just know how to bite.”) Craig Unger, a former editor at New York magazine, appears to be dazzled by all this, although it is sometimes hard to tell whether his breathlessness arises from approval, disapproval, sadness, awe or simple bewilderment. Mr. Unger, who records interviews uncritically and unreflectively, does not permit us to know exactly how he feels about his subject.

Rebekah Harkness was born in 1915 to a rich, emotionally frigid St. Louis family. She was brought up by a nanny who was chosen because she had worked in an insane asylum. She went to Fermata, a South Carolina finishing school that had sheltered Roosevelts, Biddles and Auchinclosses. There she delighted, as she wrote in her scrapbook, in setting out to “do everything bad.’' After her divorce from W. Dickson Pierce, an upper-class advertising photographer, she chose for her second husband the Standard Oil heir William Hale Harkness, who enjoyed a lofty social status, as her own family did not. He appears to have been an embarrassing sort of man; he wrote and privately published a book called ’'Totem and Topees,” which he described as a “conglomeration of uninteresting misinformation,” and followed that with a book called “Ho hum, the Fisherman,” which, he said, did not “have the excuse even of literary merit.” We are told by Mr. Unger - who is an uncomfortable stranger in the world of the rich, unused to deciphering nuances of caste - that the Harknesses’ seven-year marriage was a happy one. Little evidence is given in support of this thesis except that the two wrote a song together called “Giggling With My Feet.”

After she was widowed, Mrs. Harkness renovated her Rhode Island house; she installed 8 kitchens and 21 baths. This arrangement effectively kept her from having to see her three children on anything like a regular basis. She had a salon of sorts. She traveled a lot.

She fancied herself a composer.

She acquired a guru, also a yogi.

She married again. And again.

She was surrounded by a group her son Allen described as “all the fairies flying off the floor, the blackmailing lawyers, the weirdos, the people in the trances.” “We were the favorites,” says a dancer. “We were the loved ones.” In 1961, Rebekah Harkness became the sponsor of the late Robert Joffrey’s small ballet troupe. She did this in grand - if occasionally Marie Antoinette-ish -style. Generous, wasteful, willful, demanding and delusional, she broke with Joffrey to form the Harkness Ballet when he refused to perform the compositions she insisted on writing. In the eyes of many, she had betrayed him. “Costumes, sets, musical scores,” Mr. Unger writes, “many of the best dancers, the entire repertory - even the works choreographed by Joffrey himself - were owned by her foundation.”

“You see,” she said. “Money can buy anything.” It bought her the services of George Skibine, Marjorie Tallchief, Alvin Ailey, Erik Bruhn and Andy Warhol, but it did not guarantee her success. Mr. Unger tells us that under the direction of the dancer-choreographer Larry Rhodes the company began to garner critical raves - whereupon Mrs. Harkness fired him. Soon Clive Barnes was writing that the Harkness Ballet had “descended beyond the necessity of serious consideration,” and in 1975 it folded. She had spent the 1987 equivalent of $38 million on a failed enterprise. She rang J. D. Salinger’s bell dressed as a cleaning lady, having conceived the harebrained scheme that the reclusive writer’s short stories be put to music.

She dyed chocolate mousse blue. She dyed a cat green.

She moved hundreds of thousands of dollars from one bank to another for the pleasure of confusing her accountants. She believed in reincarnation. She filled her fish tank with goldfish and Scotch.

Her daughter Terry gave birth to a severely retarded and disabled child. For a time, Rebekah Harkness appeared to be enamored of the passive child, called Angel. Her passion, such as it was, burned itself out quickly, coincidentally with the baby’s pulling a ribbon out of her hair. Bobby Scevers, Mr. Unger writes, “had no sympathy” for the child. “So absurd,” Mr. Scevers pronounced. “When they started talking about putting the nursery over my room … I just hit the ceiling. I don’t want this screaming baby over my room! … Let the little creature die!” When she was 10 years old, she did.

Her daughter Edith jumped off roofs, swallowed pills and managed not to kill herself. “How should she do it?” Rebekah Harkness asked. “Is there a chic way to go?”

She lived on champagne and injections - Vitamin B, testosterone, painkillers - as a result of which her bathrooms were splattered with blood and her muscles calcified. (“She walked,” an acquaintance said, “like Frankenstein.”) One could almost feel sorry for her.

At the very end, according to Bobby Scevers, as she lay dying of cancer, “It was complete chaos… . It was so wonderful - everybody running around signing wills and trying on different wigs.”

Her daughter Terry hired Roy Cohn in a (failed) attempt to have her will invalidated.

Her daughter Edith killed herself. (“I’m glad Edith is gone,” said the unquenchable Bobby Scevers.

“I can’t believe it took her this long to succeed.”) Her son Allen says the years he spent in prison were the happiest of his life. He likes to talk about blowing people away. Knowing all this (and much, much more; Mr. Unger withholds no ugly or racy detail), what is it exactly that we have learned? That money can’t buy happiness? That even the rich must die? These are facts of which we have already been apprised.

One sometimes wonders if the point of all these poor-little-rich-girl/boy biographies is to lull the rest of us into a false sense of security: She is so unlike us that we are not encouraged to reflect upon our own mortality, the contemplation of which is a healthy and necessary exercise. We are meant to take comfort and a measure of relief from our difference - though, as we know but do not frequently wish to remember, the grave awaits us all.

It would be interesting to see what a social historian, someone familiar with the hierarchies of caste and class in America - or, better yet, a novelist with a theological bent - would make of the raw material Mr. Unger has gathered. I am beginning to think that biography, especially the biography of such a chaotic personality as Rebekah Harkness, needs to be molded and informed by a novelist’s ordering imagination. It might also have been interesting to see how a feminist writer would have assimilated the facts of Rebekah Harkness’s sorry life. Might Mrs. Harkness be seen as a casualty of her own doomed and defiled expectations? Unfit for mothering, unfit for ordinary love, unfit - untrained - to be the caretaker of a great fortune, was she altogether silly or altogether bad? Was she power or pawn? And how in the world did she get that way?

It is possible to write an edifying biography about an unedifying life. Jean Stein and George Plimpton did that brilliantly in “Edie,” the biography of poor Edie Sedgwick. “Blue Blood” is edifying only insofar as it raises questions about what a biography should be. A terrible story is told here. It makes no sense - and no sense is made of it.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

animatedBarbara Stanwyck as Nan Taylor in

Ladies They Talk About aka Recluse (1933) directed by Howard Bretherton & William Keighley

slap duel

Attractive Nan, member of a bank-robbery gang, goes to prison thanks to evangelist Dave Slade...who loves her.

Helen Dickson, bossy

#Barbara Stanwyck#slap duel#Ladies They Talk About#Recluse#1933#Howard Bretherton & William Keighley#Movie Poster

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Emily Dickinson Was Less Reclusive Than We Think

Emily Dickinson, Poems, Boston: Roberts Brothers (1890), Amherst College Archives & Special Collections (image courtesy the Morgan Library & Museum)

Never before have Emily Dickinson’s writings and belongings been brought together like this. Usually tucked away at various libraries and museums, the letters, daguerreotypes, and other ephemera are all under one roof for the first time at the Morgan Library & Museum. The constellation of objects in I’m Nobody! Who are you? The Life and Poetry of Emily Dickinson forms a new understanding of the poet. Mainly, it reveals a far more socially engaged Emily Dickinson than the recluse we’ve believed her to be. In fact, it might even debunk that myth.

Why does high school English introduce the poet as a recluse? Yes, Dickinson chose to socially withdraw in her late 30s, and it’s hard to say exactly why. But she was social before then, and as the many documents on view attest, remained so in some critical ways after her so-called seclusion.

So let’s dig deeper into the story before deciding whether that label is worth keeping. And let’s not pull punches — misogyny has disfigured how Dickinson’s story is told. We’re missing out on a fierce mind when we reduce her to a spinster perseverating alone in her room writing poems to the ether.

Cynthia Nixon and Jennifer Ehle in A Quiet Passion (image © A Quiet Passion/Hurricane Films/Courtesy of Music Box Films)

The new movie on Emily Dickinson, A Quiet Passion, is also on a mission to rewrite the script. When Cynthia Nixon, playing Dickinson, waves her fan and laughs besides a friend, it’s dissonant with what many of us first learned about the poet. The film dramatizes the social web the Morgan exhibition documents with its letters and mementos. Viewing the film before exploring the exhibition is a great way to internalize that Dickinson did, in fact, have a life and — gasp — friends.

So why is Dickinson remembered for her solitude in such a one-dimensional way? Starting in her late 30s, she seldom left her father’s home, where she lived. She never married. And when she was seen about town, she always dressed in white. She started to speak to visitors through her bedroom door instead of face-to-face. When her father died, the funeral took place at the family home, but she remained in her room, creaked the door open, and just listened.

But there are other facts. Chief among them, Dickinson never stopped writing. And from that so-called seclusion, she regularly wrote and mailed letters to friends and family, some of which can be seen at the Morgan. She was prolific. Her famously preserved room was effectively a busy message dispatch center.

Emily Dickinson’s bedroom, featuring the floral wallpaper on view at the Morgan, at the Emily Dickinson Museum (photo by Michael Medeiros, image courtesy the Morgan Library and Museum)

Recluses don’t generally care enough about the outside world or other people to carry on such a voluminous correspondence or always appear in a signature white outfit, now do they? Perhaps, sequestering herself from society was a poetic and artistic choice, designed to attract attention by refusing it.

Dickinson was conscious of the mystery image she was crafting. She even wrote this untitled poem, most likely in 1861, about her persona:

A solemn thing – it was – I said A Woman – white – to be And wear – if God should count me fit – Her blameless mystery –

A hallowed thing – to drop a life Into the mystic well – Too plummetless – that it come back – Eternity – until –

I ponder how the bliss would look – And would it feel as big – When I could take it in my hand – As hovering – seen – through fog –

And then – the size of this “small ” life – The Sages – call it small – Swelled – like Horizons – in my vest – And I sneered – softly – “small”!

There is something prophetic in that last stanza. Amherst townsfolk dismissed the poet’s life as small and pointless, and Dickinson softly sneered at all of them. She read Shakespeare and other great authors, tinkered with language for hours, and traded letters with publishers, which are on view at the Morgan.

So who was the Emily Dickinson behind this persona? It’s the burning question in this show. This gathering of objects gives us clues but few answers. The challenge is that we don’t have clear statements in her own words about the purpose of her seclusion, her thoughts on love, or the goals of her writing in the way that artists and writers make statements today. Much is left cryptic. So it makes it hard to definitely answer the big questions a reviewer or a biographer is supposed to answer. To make matters worse, after she died, her sister Lavinia Dickinson honored a deathbed wish and burned all the letters the poet had received from friends and family.

Photographer unknown, “Emily Dickinson” (ca. 1847), daguerreotype (Amherst College Archives & Special Collections, image courtesy Morgan Library and Museum)

Only one authenticated photographic image of Dickinson survives, and it’s on view at the Morgan. The daguerreotype, which dates to around 1847, required the poet at age 16 to sit still for a long time as the image developed. Because it’s the only authenticated image, it’s taken on an outsized role in representing the poet. Its rigidity and stoicism, likely caused by the daguerreotype process — no one can smile forever — has perpetuated her image as Puritan recluse. Even her siblings complained it was “too solemn, too heavy and that it had none of the play of light and shade in Emily’s face.”

The Morgan is also displaying another, recently discovered daguerreotype that fiercely divides scholars. Some experts believe this image shows Dickinson in her late 20s with Kate Turner, whom some believe was her lesbian lover but all can agree they were at least friends. We know for sure it’s Kate Turner because of comparison with other verified images. It’s harder to confirm the other woman is Dickinson because we only have that one image. It’s even harder to verify these two women had a romance. And when Turner sent her letters from Dickinson to the publishers, she sent copies and not originals. We will never know for sure if she redacted them. Though I’d be wary to make bold claims here and cast a woman who didn’t marry and departed from gender norms as a closeted lesbian. Her father was rich and tolerant enough that she didn’t have to marry to survive. She may have just wanted a room of her own.

“I am nobody, who are you?” Dickinson jests in her famous poem, after which the show is named. As the poem let’s on, mystique entices and intrigues us more than those who loudly flaunt their existence. Perhaps that explains part of the poet’s enduring appeal.

I’m Nobody! Who are you? Are you – Nobody – too? Then there’s a pair of us! Don’t tell! they’d advertise – you know!

How dreary – to be – Somebody! How public – like a Frog – To tell one’s name – to the livelong June – To an admiring Bog!

Emily Dickinson, Untitled (I’m Nobody! Who are you?) Poem in Fascicle 11 (ca. late 1861) (Houghton Library, Harvard University, image courtesy Morgan Library and Museum)

I’m Nobody! Who are you? The Life of Poetry of Emily Dickson continues at the Morgan Library & Museum (225 Madison Ave, Midtown East, Manhattan) through May 28.

The post Emily Dickinson Was Less Reclusive Than We Think appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2qX9TUQ via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

(PCxPC) First fateful meeting between Dick (@chronosbled) and Eri~! Wonder what these two would end up doing later~?

#ok for some reason#tumblr is not letting me tag speka properly#tumblr#TUMBLR#Im gonna beat you tumblr#dont try me#dol#dol related#degrees of lewdity#dol pc#dickson the recluse#dickson the serial killer#eri the veil#fan art#art#mine#my fan art#my art#OUUGUHGHIGUH I LOVE THESE TWO SO MUCH I NEED TO INJECT THEM STRAIGHT INTO MY VEINS SPEKA

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Audiobook has been published on http://www.audiobook.pw/audiobook/secret-garden-11/

Secret Garden

Few children’s classics can match the charm and originality of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, the unforgettable story of sullen, sulky Mary Lennox, the most disagreeable-looking child ever seen. When a cholera epidemic leaves her as an orphan, Mary is sent to England to live with her reclusive uncle, Archibald Craven, at Misselthwaite Manor. Unloved and unloving, Mary wanders the desolate moors until one day she chances upon the door of a secret garden. What follows is one of the most beautiful tales of transformation in children’s literature, as Mary her sickly and tyrannical cousin Colin and a peasant boy named Dickson secretly strive to make the garden bloom once more. A unique blend of realism and magic, The Secret Garden remains a moving expression of every child’s need to nurture and be nurtured&mdash,a story that has captured for all time the rare and enchanted world of childhood.

0 notes

Photo

George Harrison, 1966; photo by Nigel Dickson.

“‘I asked to be successful,’ [George] said. ‘I never asked to be famous. I can tell you I got more famous than I wanted to be. I never intended to be the Big Cheese.’” - Evening Standard, 18 March 1966

“People used to say George was a recluse, but he would say: ‘well, I just don't go where you go,’ or ‘I don’t go where the press is, or to those sorts of places.’ We had a lot of friends and had quite a social life. You can put on this other persona and be low key about it. We never traveled with anybody, we just went on our own. George traveled on his own. The less attention you call to yourself the easier it is. That was his philosophy.” - Olivia Harrison, The Australian, 3 March 2005

“My dad was always, ‘Don’t be famous. Don’t envy this. Be a musician, but don’t be famous. You lose all your freedom and you can’t do anything. You have to live a different life.’ We were both private people, and he did a really great job of keeping me out of the press all my life.” - Dhani Harrison, New York Times Syndicate, 15 March 2013 (x)

#George Harrison#quote#quotes about George#quotes by George#George and fame#1966#1960s#Beatlemania#The Beatles#George and Olivia#George and Dhani#fits queue like a glove

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

cw // suggestive

(PCxPC) Today's serving of DickEri with @chronosbled. I'm just,,,, I'm very yuripilled rn give me a moment guys. Dick discovered what the mysterious pink liquid does...

#UUURHGUHUGHG I GET TO DRAW GIRLS LOVING GIRLS AND BEING TOXIC WITH EACH OTHER#IM HAVING SO MUCH FUN#THE BRAIN JUICES ARE FLOWING RIGHT NOW#BUT IM SO BUSY HUHUHGHUH#ngl im happy with how it turned out but drawing them kissing almost killed me#chronosbled#Dickson the Recluse#Dickson the Serial Killer#Eri the Veil#fan art#art#mine#my fan art#my art#dol#dol related#degrees of lewdity#dol pc#suggestive cw#suggestive

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

{ Not on the right blog, but if it's okay, can I request my girl Dickson in D4 for the expression meme please? }

♡ Send me a DOL Character/PC + Expression! - Deeppink-man Expression Meme (OPEN!)

Hi Hi Speka!! No problem, I'll just tag it here hehehe @chronosbled <3 It's always a pleasure to draw the babygirl!!!

She probably saw Eri 'branding' herself to appease her. Little Pervert.

#ask dean#dean replies#fan art#art#mine#my fan art#my art#chronosbled#dash games#expression meme#dickson the recluse#dickson the serial killer#degrees of lewdity#dol#dol related#dol pc#HUHEUHEUEUHEU I HOPE YOU ENJOY IT SPEKA !!!!! I HAD A LOT OF FUN#i can't believe i said i'll do it once im free but i saw this and went i need to do it NOOOWWWWWW#anyways hehehe enjoy it ~!!

24 notes

·

View notes