#Eko and Iko

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

aba abe abh abi abo abu acha ache achi acho achu ada ade adh adi ado adu afa afe afh afi afo afu aga age agh agi ago agu aha ahe ahi aho ahu aja aje aji ajo aju aka ake akh aki ako aku al ala ale alh ali alo alu am ama ame ami amo amu an ana ane ani ano anu apa ape aph api apo apu ar ara are arh ari aro aru asa ase ash asi aso asu ata ate ath ati ato atu ava ave avi avo avu az aza aze azh azi azo azu ba bal bam ban bar baz be bel bem ben ber bez bha bhe bhi bho bhu bi bil bim bin bir biz bo bol bom bon bor boz bu bul bum bun bur buz cha chal cham chan char chaz che chel chem chen cher chez chi chil chim chin chir chiz cho chol chom chon chor choz chu chul chum chun chur chuz da dal dam dan dar daz de del dem den der dez dha dhe dhi dho dhu di dil dim din dir diz do dol dom don dor doz du dul dum dun dur duz eba ebe ebh ebi ebo ebu echa eche echi echo echu eda ede edh edi edo edu efa efe efh efi efo efu ega ege egh egi ego egu eha ehe ehi eho ehu eja eje eji ejo eju eka eke ekh eki eko eku el ela ele elh eli elo elu em ema eme emi emo emu en ena ene eni eno enu epa epe eph epi epo epu er era ere erh eri ero eru esa ese esh esi eso esu eta ete eth eti eto etu eva eve evi evo evu ez eza eze ezh ezi ezo ezu fa fal fam fan far faz fe fel fem fen fer fez fha fhe fhi fho fhu fi fil fim fin fir fiz fo fol fom fon for foz fu ful fum fun fur fuz ga gal gam gan gar gaz ge gel gem gen ger gez gha ghe ghi gho ghu gi gil gim gin gir giz go gol gom gon gor goz gu gul gum gun gur guz ha hal ham han har haz he hel hem hen her hez hi hil him hin hir hiz ho hol hom hon hor hoz hu hul hum hun hur huz

iba ibe ibh ibi ibo ibu icha iche ichi icho ichu ida ide idh idi ido idu ifa ife ifh ifi ifo ifu iga ige igh igi igo igu iha ihe ihi iho ihu ija ije iji ijo iju ika ike ikh iki iko iku il ila ile ilh ili ilo ilu im ima ime imi imo imu in ina ine ini ino inu ipa ipe iph ipi ipo ipu ir ira ire irh iri iro iru isa ise ish isi iso isu ita ite ith iti ito itu iva ive ivi ivo ivu iz iza ize izh izi izo izu ja jal jam jan jar jaz je jel jem jen jer jez ji jil jim jin jir jiz jo jol jom jon jor joz ju jul jum jun jur juz ka kal kam kan kar kaz ke kel kem ken ker kez kha khe khi kho khu ki kil kim kin kir kiz ko kol kom kon kor koz ku kul kum kun kur kuz la lal lam lan lar laz le lel lem len ler lez lha lhe lhi lho lhu li lil lim lin lir liz lo lol lom lon lor loz lu lul lum lun lur luz ma mal mam man mar maz me mel mem men mer mez mi mil mim min mir miz mo mol mom mon mor moz mu mul mum mun mur muz na nal nam nan nar naz ne nel nem nen ner nez ni nil nim nin nir niz no nol nom non nor noz nu nul num nun nur nuz oba obe obh obi obo obu ocha oche ochi ocho ochu oda ode odh odi odo odu ofa ofe ofh ofi ofo ofu oga oge ogh ogi ogo ogu oha ohe ohi oho ohu oja oje oji ojo oju oka oke okh oki oko oku ol ola ole olh oli olo olu om oma ome omi omo omu on ona one oni ono onu opa ope oph opi opo opu or ora ore orh ori oro oru osa ose osh osi oso osu ota ote oth oti oto otu ova ove ovi ovo ovu oz oza oze ozh ozi ozo ozu pa pal pam pan par paz pe pel pem pen per pez pha phe phi pho phu pi pil pim pin pir piz po pol pom pon por poz pu pul pum pun pur puz ra ral ram ran rar raz re rel rem ren rer rez rha rhe rhi rho rhu ri ril rim rin rir riz ro rol rom ron ror roz ru rul rum run rur ruz sa sal sam san sar saz se sel sem sen ser sez sha she shi sho shu si sil sim sin sir siz so sol som son sor soz su sul sum sun sur suz ta tal tam tan tar taz te tel tem ten ter tez tha the thi tho thu ti til tim tin tir tiz to tol tom ton tor toz tu tul tum tun tur tuz uba ube ubh ubi ubo ubu ucha uche uchi ucho uchu uda ude udh udi udo udu ufa ufe ufh ufi ufo ufu uga uge ugh ugi ugo ugu uha uhe uhi uho uhu uja uje uji ujo uju uka uke ukh uki uko uku ul ula ule ulh uli ulo ulu um uma ume umi umo umu un una une uni uno unu upa upe uph upi upo upu ur ura ure urh uri uro uru usa use ush usi uso usu uta ute uth uti uto utu uva uve uvi uvo uvu uz uza uze uzh uzi uzo uzu va val vam van var vaz ve vel vem ven ver vez vi vil vim vin vir viz vo vol vom von vor voz vu vul vum vun vur vuz za zal zam zan zar zaz ze zel zem zen zer zez zha zhe zhi zho zhu zi zil zim zin zir ziz zo zol zom zon zor zoz zu zul zum zun zur zuz

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch "The Disturbing Story Of The Albino Ecuadorian "Circus Slaves" Eko and Iko - Lights Out Podcast #73" on YouTube

youtube

0 notes

Photo

George and Willie Muse were black albino brothers exploited as sideshow freaks in the American south who gained international fame. “It’s the best story in town, but no one has ever been able to get it.” That’s what journalist Beth Macy was told by colleagues when, at the end of the 1980s, she moved to Roanoke, a former railroad town in rural Virginia. The story they were talking about, handed down through generations, was the stuff of marvel and melodrama, of folk horror, of racial terror and its impact on the most vulnerable Americans. It concerned George and Willie Muse, albino brothers who were taken from a tobacco farm in Truevine, near Roanoke in Virginia, by a circus promoter and spent more than a decade touring the country as sideshow freaks.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Congress of Freaks of Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, 1929. The sideshow performers include Eko and Iko, three giants, a snake charmer, a sword swallower (in mid-swallow) and over a dozen more.

Photo: Edward Kelty via LiveAuctioneers

#New York#NYC#vintage New York#1920s#Edward Kelty#Congress of Freaks#freaks#freakshow#circus#Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus#sideshow#Eko & Ilko#sword swallower#snake charmer

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the year 1899, two African-American brothers with albinism were forcibly taken and exploited as performers in a circus.

Renowned as "The Sheep-Headed Men," "The White Ecuadorian Cannibals Eko and Iko," and "The Ambassadors From Mars," George and Willie Muse gained worldwide fame as sideshow performers during the early 1900s. However, the true horrors of their story remained largely unknown to their predominantly white audiences.

Born with a rare form of albinism in the African-American community, the Muse brothers fell victim to a traveling "freak hunter" who targeted them when they were young boys and forcibly abducted them from their home in Virginia. Their distinctive appearance, characterized by African-American albinos with pale blue eyes and blond hair, coupled with their poor vision due to an eye condition often misunderstood as a mental impairment, made them easy targets for exploitation by a traveling circus.

Under the control of their captors, the brothers were compelled to grow out their hair and were sold to various traveling sideshows, including Ringling Bros. Circus. Despite being denied access to education and literacy, as well as being deprived of any financial compensation, George and Willie possessed remarkable musical talents. They could hear a song once and flawlessly reproduce it on any instrument they were handed, be it a guitar, banjo, harmonica, saxophone, or xylophone. Their handlers greatly underestimated their abilities.

Their years of enslavement finally came to an end in 1927 when Ringling Bros. Circus returned to Roanoke, and George recognized their mother among the crowd. Overwhelmed with emotion, George exclaimed, "There's our dear old mother. Look, Willie, she is not dead." This poignant reunion marked the turning point in their lives, bringing an end to their captivity and the beginning of a journey towards reclaiming their freedom and identity.

#african-american#1899 photo#1899#photography#The Sheep-Headed Men#ringling bros circus#african-american history

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

These are the Muse Brothers. Their biological names are George and Willie Muse. They were two albino brothers; the grandsons of former slaves and sons of tobacco sharecroppers born in Roanoke, Virginia, in the 1890’s. In 1899 George and Willie Muse were kidnapped as boys in Truevine, Virginia by bounty hunters and were forced into the circus, labeled as “freak show” performers. Upon their capture, they were falsely told that their mother was dead and that they would never return home .Their owners showcased the brothers in circuses where they were exploited for profit in so-called freak shows. The Muse Brothers became famous across the United States as “Eko and Iko”, the “White Ecuadorian Cannibals”, the “Sheep Headed Men”, the “Sheep Headed Cannibals”, the “Ministers from Dahomey” and “Ambassadors from Mars���.George and Willie were forced to grow their hair into massive “dreadlocks“ which together with their white skin and bluish eyes were exhibited as rarities. They were also billed as “Darwin’s Missing Links” and “Nature’s Greatest Mistakes”. The boys were not permitted to go to school, neither were they paid for their work. They were literally kept in slavery, earning nothing despite thousands of people who paid to see them. Their only rewards were clownish attire they wore for the shows and food meant to keep the ‘assets’ alive.One of their owners had found that George and Willie harboured the ability to play any song on almost any instrument, from the xylophone to the saxophone and mandolin, and that made them even more famous and more valuable ‘assets’ to owners of travelling circuses. However, after all this time, their illiterate mother had not ceased looking for her boys.In the fall of 1927, the brothers were on a tour with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus to Roanoke, little did the boys know they were coming home from which they had disappeared nearly three decades back. It came to their mother’s attention that the The Greatest Show On Earth was in town and she was determined to find them. It was a tough decision to confront the Ringling Brothers who were powerful multimillionaires who also had the attention of the heavyweight politicians and law enforcement agencies.Their mother tracked them down and eventually found the boys working for the Ringling Brothers circus and surprised them while they were on stage and their family reunited, 28 years later since they had gone missing in the very same town. The poor and powerless black woman stood up to police and big shot circus owners and successfully took her sons home.

#BLACKHISTORY

If yall want to read more about it: Here

#Black History Month#George Muse#Willie Muse#The Muse Brothers#Albino Brothers#Albino#Ringling Bros#Circus#Black Men#Black Man#Black History

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

«komi yu panchu iko kumo yameyo gwajo twai eko kai»

“You shouldn’t pick flowers from the same plant twice in a day.”

A proverb in Paiya. Picking flowers for your vases or kwaiko is a springtime tradition. But while picking, be mindful not to remove too many flowers from one plant. Flowers are important to the plant’s growth, so only take one or two per plant. Don’t change too much in one day. Make your changes and let it sit. By rushing you might over look that you’ve picked all the flowers off a plant.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are the Muse Brothers. Their biological names are George and Willie Muse.

They were two albino brothers; the grandsons of former slaves and sons of tobacco sharecroppers born in Roanoke, Virginia, in the 1890’s.

In 1899 George and Willie Muse were kidnapped as boys in Truevine, Virginia by bounty hunters and were forced into the circus, labeled as “freak show” performers. Upon their capture, they were falsely told that their mother was dead and that they would never return home .

Their owners showcased the brothers in circuses where they were exploited for profit in so-called freak shows. The Muse Brothers became famous across the United States as “Eko and Iko”, the “White Ecuadorian Cannibals”, the “Sheep Headed Men”, the “Sheep Headed Cannibals”, the “Ministers from Dahomey” and “Ambassadors from Mars”.

George and Willie were forced to grow their hair into massive “dreadlocks“ which together with their white skin and bluish eyes were exhibited as rarities. They were also billed as “Darwin’s Missing Links” and “Nature’s Greatest Mistakes”.

The boys were not permitted to go to school, neither were they paid for their work. They were literally kept in slavery, earning nothing despite thousands of people who paid to see them. Their only rewards were clownish attire they wore for the shows and food meant to keep the ‘assets’ alive.

One of their owners had found that George and Willie harboured the ability to play any song on almost any instrument, from the xylophone to the saxophone and mandolin, and that made them even more famous and more valuable ‘assets’ to owners of travelling circuses. However, after all this time, their illiterate mother had not ceased looking for her boys.

In the fall of 1927, the brothers were on a tour with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus to Roanoke, little did the boys know they were coming home from which they had disappeared nearly three decades back.

It came to their mother’s attention that the The Greatest Show On Earth was in town and she was determined to find them. It was a tough decision to confront the Ringling Brothers who were powerful multimillionaires who also had the attention of the heavyweight

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

soaring, carried aloft on the wind…continued 13

A story for Xichen and Mingjue, in another time and another place.

The Beifeng, the mighty empire of the north, invaded more than a year ago, moving inexorably south and east.

In order to buy peace, the chief of the Lan clan has given the Beifeng warlord a gift, his second oldest son in marriage. However, when Xichen finds out he makes a plan.

He, too, can give a gift to the Beifeng warlord, and he will not regret it.

Part 1: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 8 / 9 / 10 / 11 / 12 / 13 … HOME

It’s on AO3 here if that’s easier to read.

NOTES: This chapter is Explicit.

For translations of the entirely fictitious Beifeng language, you’ll have to scroll to notes. I’m only going to translate something that’s not clear in the text. Sadly, there’s just not any other good way to do it on Tumblr!

Chapter 13

The weather shifts abruptly in autumn: one day sunny skies and crisp air, the next thick clouds and a biting wind that rolls down from the west. It’s a bittersweet reminder of the Cloud Recesses, but Xichen decides he likes it. He likes wool and fur-lined jackets, he likes the way the clouds are painted in shades of grey, and he likes the patter of rain on the canvas roof of his tent.

He’s busier now, too. The Ikarahu are moving again slowly, so slowly it is nearly imperceptible, but in the last two weeks, Xichen has noticed that the tent lines are shifting. Where he was once on the easternmost edge of the camp, he is now nearly in the middle, and the horse yards have moved from the northwest to the east, closer to Jinlin Tai. There are more in-camp injuries to care for and more battle wounds to heal. The Ikarahu are growing impatient, Xichen thinks, and he wonders how much longer the Jin can withstand the siege.

One evening—Xichen has lost track of the exact days—Huaisang, Qingyang, and Mingjue all come to dinner, and Xichen is immediately suspicious. Qingyang, in particular, has a wicked smirk on her face, and Mingjue looks far too pleased with himself.

“Zewu-Jun, it has come to my attention that you have kept a secret from us,” Huaisang announces.

Xichen’s blood turns to ice. How could they possibly have found out? Would this dissolve the treaty? No. No. Regardless of whether or not he alone changed the terms, the Ikarahu agreed to accept it, to accept him. They must honor it. They must. He stumbles backward a step, and Mingjue reaches out to steady him, a puzzled look on his face.

“Weren’t you going to tell us it was your birthday?” Huaisang continues, and Xichen stares.

His birthday. Is it his birthday? He blinks, thinking. It could be.

“Is it the eighth of the month?” he asks, still numb from the vestiges of prickling fear. If so, he has been here a little over two months. Only two months.

Huaisang nods. “Lucky thing I read treaties to put myself to sleep on lonely nights,” he jokes—Xichen does not flinch—and hands him a square wrapped in brightly striped fabric, followed by Qingyang, who hands him a short bamboo tube.

Xichen has to sit, overwhelmed by the surprise. Birthdays were not important in the Cloud Recesses, although they were usually acknowledged with well wishes and small tokens. He isn’t sure how to react.

“Well?” Qingyang says impatiently, when Xichen doesn’t move. ”Open them!”

Xichen does, fumbling with the pleasure of gifts and the constant surprise of friendship. Qingyang has given him a drawing of himself and Mingjue during that first sword fight. She is a splendid artist and somehow captured the motion of battle with simple, elegant, perfectly placed brushstrokes. Even the negative space inside the brushstrokes speaks of movement and action. Xichen’s robes seem to swirl around him, sword arm arching back, and Mingjue is raising his ipira to block. Xichen touches the expressions on their faces: his looks intent and serious, but there’s the tiniest hint of a smile on Mingjue’s. Xichen is nearly speechless.

“Qingyang, why have I never seen your maps?” he asks, squeezing her hand. “They must be beautiful. This is wonderful, thank you.”

Huaisang’s gift is a book of music Xichen hasn’t seen before, some folk songs and some that look like power lurks in their notes. The pages all seem different, as though they came from different sources, and they are bound in a greenish-blue leather that looks like the deepest water of the river that flows through the Cloud Recesses. Xichen gapes at it. He has no idea how leather could be this shade of blue. It must have been exorbitantly expensive or made by magic. Or both.

“It is too much, Huaisang,” he protests, but Huaisang waves him off.

“Trust me, I owe you more than that. This is the longest we’ve gone without anakau trying to throw me or anyone else off a cliff.”

Xichen has gotten used to Huaisang’s teasing and just smiles.

“Thank you, anati,” he teases back, ruffling his hair and calling him little brother. To his delight, it’s Huaisang who blushes.

“Edas ahora,” Mingjue pulls Xichen to his feet and hands him a long tube with leather straps, itself an intricate marvel. “For you.”

Xichen looks at the wooden tube, the length of an iraho, carved and painted with fantastical beasts—lions with wings, tigers with two heads, fiery birds—all beautiful beyond words. He reverently traces the lines of one coiled dragon before he opens the case. When Xichen pulls out the iraho, all the air vanishes from his lungs. It is so much more than a sword. It is a sublime weapon, perfectly balanced, meant for an emperor or an immortal, not for Xichen. The scabbard and pommel are white jade inlaid with silver in a pattern that seems random, except it reminds him of something, almost like the crackle of frost. The handguard has a blue stone set in the center of the design. And the iraho itself—Xichen has never seen anything like the blade. The metal is cold and pale, rippling in the light as though it is alive.

“What...what is it?” he asks reverently, touching the spine.

Mingjue says something, too many words for Xichen to follow, so Huaisang translates.

“It’s an ice blade,” he says. “Only a few artisans in our country still make them, but this one…” He pauses, choosing his words more carefully than usual. “This one is older and different. It has a name, for one thing, Sikunadis. We think that’s because ‘tadis sikun’ means ‘‘bright heart.’ It has a sister, Kaumadis. ‘Tadis kauma’ is ‘dark heart.’ They’re old enough that we’re not entirely sure.”

He nods to Mingjue, and Xichen realizes that he means the ipira Mingjue carries, which does have a similar pattern of fault lines, now that Xichen thinks about it, except that where Sikunadis is white, Kaumadis’s scabbard and pommel are black. Kaumadis’s blade is dark, although it has the same shifting, undulating appearance, and of course, the stone on its handguard is a deep crimson.

“They were created from the same vein of metal by the same master using the same magic, although as you can see, they took different paths during forging. They can hold magic, maybe even your magic, and they have continued to be in our family for generations.”

Xichen hears the words Huaisang is not saying and fully understands how precious this gift is. It is not one that can be refused, even if he were so inclined, and he is not. He wants to keep this beautiful sword badly, enough that he feels lightheaded with the desire. It occurs to him to wonder when and how Mingjue brought this sword to the Ikarahu camp, but he doesn’t allow himself to consider any of the answers his heart wants to believe most.

Xichen kisses Mingjue lightly, mindful of their audience, but he lingers to rub his nose against Mingjue’s. “Tiras mau, Etikuntiga.”

Judging by the expression on his face, Xichen isn’t sure Mingjue is going to allow Huaisang and Qingyang to stay for dinner—Xichen isn’t even sure he does—but Mingjue relents for the exact amount of time it takes to finish eating and then gives Huaisang a narrow-eyed look that makes Huaisang roll his eyes.

“Ipira’orhew Ikira, you are a tyrant,” he grumbles.

Qingyang grins. She cups her hands and bows deeply. “Happy birthday, my friend.”

Huaisang takes Xichen’s hand and tugs, pulling Xichen down to kiss him on both cheeks. “To long life, swift horses, and blue skies,” he says, and then adds, more softly and mysteriously, “Thank you.”

He shoots Mingjue an aggrieved look, but Mingjue just waves his hand, shooing his brother, and Xichen bites his lip to keep from laughing.

Qingyang doesn’t resist, laughing and draping her arm over Huaisang’s shoulder to lead him away. “Aurakat, I will let you buy me a drink to celebrate our dear friend Xichen’s birthday, and I won’t even complain when you inevitably whine about your tragic love life. Is that acceptable?”

Xichen turns to ask Mingjue why Huaisang had thanked him, but the words are lost and the thought disappears as Mingjue meets him with hungry lips, ravishing his mouth as soon as the tent flap closes. The hands on his body are equally greedy, and Xichen steps into the embrace, wrapping his arms around Mingjue’s neck, pulling him closer, just as eager. Mingjue sweeps Xichen into his arms to carry him to the bed and lay him down, but Xichen stops Mingjue before he can get any further.

“I want to see your hair down.” Xichen touches the braids. “Kami teko parau?”

It’s not quite the right words, but Xichen hopes that between the two languages, it’s close enough. Mingjue’s reaction surprises him. His mouth curves into a wicked smile, and he tips Xichen’s head back, kissing him hard, thrillingly harder than usual, sliding his other hand inside Xichen’s robes to rest on his chest, just above his heart.

“Ani, aitapaho, iko eko paka,” he says, and Xichen hesitates.

“Should I not?” he asks. He’s never seen Mingjue’s hair down, only either tightly coiled or loosely arranged. Perhaps it is not allowed.

Mingjue’s smile broadens. “You may. It is…” The dimples deepen, and Xichen’s heart rate climbs. “It is a sacred vow,” he laughs and turns to settle on the bed between Xichen’s legs.

Xichen still doesn’t know exactly what he means, but he reverently touches the thick cluster of braids and tugs at it, looking for the circular pins that hold it. He collects them in a pile until the braids drop from their tight knot. They’re longer than Xichen expected, falling to Mingjue’s mid-back, and even plaited, they’re soft to touch. He runs his fingers through them and Mingjue makes a humming noise of contentment. Xichen’s fingers yearn to undo all of them, even though there must be close to a hundred. He wavers, still uncertain, and Mingjue looks back at him, eyebrow raised. He takes one of the braids and pulls off the thread that binds it, undoing the plait and shaking his head.

Swiftly, Xichen starts unfastening the rest of the braids. Mingjue seems to be enjoying himself, exhaling like a purring cat and rubbing his hands over Xichen’s legs and inner thighs while he works, occasionally adjusting to lean against Xichen’s groin in a very distracting way.

By the time the last braid is undone, Xichen is nearly breathless with arousal. The unbound length of Mingjue’s hair is as sublimely beautiful as the rest of him, wavy from the braids, with a reddish hue in the golden light of Xichen’s tent.

Xichen sinks his hands into the thick mass, scratching Mingjue’s scalp and running his fingers all the way to the edge. Mingjue turns his face to touch his lips to Xichen’s jaw. It is such a gentle, loving gesture, it ignites an immediacy in Xichen born of more than only lust. His heart, his soft heart, is pounding with unspoken words, and he suddenly needs to feel Mingjue’s skin against his. Xichen tugs at Mingjue’s clothes ineffectively, not exactly pulling any of the right places, but Mingjue obliges him, sliding off his jacket and generously removing his tunic without Xichen even needing to ask.

Kneeling to face Xichen, he shakes his head with mock sorrow. “Your clothes. Too many.”

So Xichen takes Mingjue’s hands and sets them on his belt. “Take them off,” he agrees.

Mingjue has become skilled at unfastening the many layers of robes and underclothes Xichen usually wears, and in exchange, Xichen has started wearing fewer of them. Today, he has only two robes, an undershirt, and the wide-legged pants the Ikarahu prefer. Mingjue grins when he realizes it and pulls Xichen’s shirt off with a flourish that makes him laugh. Mingjue leans forward to kiss Xichen, and his waterfall of hair covers them both, tickling Xichen’s neck and chest, turning the laughter into restless hunger.

“Xichen?” Mingjue asks, brushing his nose against Xichen’s ear, sending tingling sparks surging down his back and neck. “I want…with you...pikodau? Hm...sex?”

He sounds unsure in a way that makes Xichen smile, and he feels a little bad for what Huaisang’s efforts to teach Yuyan to Mingjue must be like. “We have. We do.”

Mingjue’s grin is a sideways tilt of his lips that makes him look charming and boyish, and Xichen tucks a loose strand of wavy hair behind his ear. “Yes, piko. It is good. Pikodau is different sex.” For once, Mingjue is the one who flushes, and he gives up trying to explain. “Trust me?”

Xichen does, especially here in this bed, where Mingjue is always attentive, always accommodating. And that blush, the one that scatters a rosy tint over the creases of Mingjue’s dimples—Xichen finds that he is willing to risk much for that blush. He wraps his arms around Mingjue’s neck and kisses him roughly, not certain what Mingjue is asking for, but certain he can trust him.

As is ever the case, he loses himself in the intensity of Mingjue’s demanding hands and mouth and hardly notices when Mingjue slips his pants down over his hips. He’s surprised when Mingjue rolls him on his stomach, though, and he’s thoroughly shocked when he feels warm breath on his buttocks. This is something new and strange and, he feels, entirely inappropriate. He doesn’t like that he can’t see what Mingjue is doing, but the hands on his back are soothing, even when they angle his hips up, and he relaxes.

Trust, he reminds himself.

“Mingjue, oh, no, please,” he stutters when he feels Mingjue’s tongue graze against his hole, but he leans into it anyway, his body reacting before his thoughts can process. When his dazed mind catches up, he corrects his words so there is absolutely no confusion. “Yes, please, ani.”

The first time Mingjue had touched Xichen there with wet, oil-slicked fingers, Xichen had nearly passed out. He wasn’t entirely innocent—he understood how such a thing could be necessary. It never occurred to him that it was desirable until he had heard himself moaning and pleading for more, and more, even more, and had climaxed with Mingjue’s fingers deep inside him.

Now, though, he doesn’t even recognize the keening sound of his voice. The hard and soft feel of Mingjue’s tongue against him, dipping into him, is worlds and stars beyond his wildest spring dreams. Mingjue wraps a hand around Xichen’s waist, reaching to stroke his cock, too, and Xichen is made of fire, kindling wherever Mingjue is touching him. It’s almost too much to bear, but when he stops, Xichen falls back onto the bed with a disappointed whine he can’t quite suppress. The Ikarahu may not believe in gods, but at this moment, Xichen certainly does.

Mingjue reaches into the pocket of his discarded pants and pulls out a small jar. He pours oil onto his palm, coating his fingers into the small pool and spreading it along the length of his shaft. With courageous effort, Xichen moves his liquid arms and legs so he can watch Mingjue with hazy eyes, understanding now what he was asking for, and debates whether or not this is something he wants. It is not a long debate. It is, in fact, simple. Inexplicable and unlikely as it is, he wants Mingjue, any way he can have him. Every way he can have him. Not only for a treaty, not only for duty, but for himself. What monotony his life would have been, he thinks, if he had not made this choice, and he opens his mouth to tell Mingjue.

But the words dissolve in his throat as Mingjue kisses the corner of Xichen’s knee and asks again, asks with his eyes and his hands and his mouth. “Xichen, yes?”

In answer, Xichen lets his legs relax and fall to the side, a curving smile shaping brazen lines on his face and Mingjue’s hissed curse and groan. “Mingjue, yes.”

Less tenderly than usual, and more like he is fighting his own shaking desire, Mingjue slides his finger inside Xichen, distracting him from the momentary discomfort by kissing his neck and nipping the edge of his collarbone. He curls his other hand around Xichen’s cock again, and there is nothing but the pleasure that shivers in great sheets across his skin. Mingjue’s finger—fingers, now—move inside him, and Xichen is eager to moan, eager to urge Mingjue on with his voice.

“Please, more, touha, ako,” he begs in both languages, and Mingjue chuckles, but it is tinged with an edge of barely restrained frenzy.

“Aitapaho, ek eko mau Sikunadis, my bright heart. Eina katu sima aki akiti eko?” Mingjue tells him between kisses. “Da atem okira auha di teko kiria.”

Xichen is throbbing, the blood in his body threatening to explode out from him. He can not think to translate anymore. He can not. He grabs Mingjue’s face between his hands and looks into his eyes, the nearly black circles wide with surprise.

“Mingjue, stop talking and just fuck me.” He’s never used the word “fuck” before, but this seems like the right time to start. “Etikuntiga...pikodau...ako.”

Mingjue’s groan is half whimper, half sob, and he drops his head to rest on Xichen’s chest, but he shifts, adding more oil, adjusting himself, and adjusting Xichen with trembling hands that are usually so confident and sure. He is hot and hard and wet against Xichen, and Xichen can’t quite comprehend how he can so powerfully want something he’s never experienced.

With a shaky sigh that already sounds overcome, Mingjue enters him, gradually pressing in, and Xichen immediately thinks he’s made a mistake. This will not work. They will not fit this way. The fullness is uncomfortable and unfamiliar and not immediately enjoyable. But Mingjue is slow and patient, despite, Xichen notices, his muscles quivering with the effort. He takes one of Xichen’s hands and kisses the palm, nibbling the tips of Xichen’s fingers, which is enjoyable. Very gently, he leans his hips forward and Xichen gasps at how something uncomfortable can quickly turn into something absolutely imperative.

“Aitapaho? Yes? Ereda sinedi?”

“Oh...…” Xichen manages, arching his back off the bed. It is better now, so much better, and the sparks that burst through him are different, in the way lanterns differ from the sun. “Ani, yes, continue.”

It is the last coherent thought he has, because Mingjue starts to move, pulling out of him and pushing in, and Xichen is consumed. He hadn’t known, he thinks. No one had told him that there could be pleasure like this in the world, that having someone—no, not just someone, Mingjue, only Mingjue—in his bed, in his life, in his body could so unmake him and fulfill him.

The constant fireworks spread out under his skin, and he strokes himself, matching Mingjue’s speed, watching his eyes roll back, his mouth slack with panting desperation. He should not feel such pride in Mingjue’s passion for him, but he does, and a fiercely possessive sliver of his heart wants to see more.

“Ah...Huan...let me...help,” Mingjue says, holding Xichen’s hand in his, sliding along Xichen’s cock with him, repeating his name over and over.

It's the first time Mingjue has ever used his birth name, and he pronounces it with two syllables, as it would be in Orera: who-ahn. Xichen hadn’t even realized how much he missed his name and missed what it meant to have someone know him enough to use it. Family. Friends. Confidants. Even if it is only through sex, even if it does not meant to Mingjue what it means to Xichen, feeling known is indescribable. Even when the sounds run together like nonsense, they still sound like music to Xichen.

Xichen’s breathing is ragged and panting uncontrollably, teetering on the sharp edge between pleasure and release, his mind whirling with thoughts and feelings too immense to capture in words. It will never be exactly this way again. He will change, he has changed, for good or ill, and he wants to capture this moment, this singular moment, to remember it forever, to shield him against the uncertainty of the future.

The sudden vehemence of his orgasm takes Xichen by surprise, flexing muscles across his body, even down to the arches of his feet. Everything feels dull and sharp at once, and he wants more and less, he wants to scream and laugh.

Mingjue’s moans take on new, feral tones that vibrate through Xichen. He falls forward, catching himself on his hands and kisses Xichen madly, furiously. Xichen plunges his hands through Mingjue’s thick hair to the back of his head, anchoring his mouth, and he tastes like the fierce jubilation of love. In three powerful thrusts Xichen feels in his chest, Mingjue climaxes, clutching Xichen tightly to him and filling him with a shocking burst of heat before collapsing against him.

Xichen vows to never move again. When Mingjue tries to shift his weight off of him, Xichen wraps his arms and legs around him and growls a warning, which makes Mingjue laugh weakly.

“No. Stay,” he commands, and Mingjue acknowledges with a chuffing exhale, tucking his head under Xichen’s chin.

Finally, though, even under Mingjue’s enveloping warmth, Xichen gets cold. Reluctantly, he gets up to clean himself and Mingjue before he leaves. It is how their evenings usually end, but this time, when they are done, Mingjue pulls Xichen back down to the bed.

“Wait. I have a gift.”

He gets a clay pot from the pocket of his long wool coat and opens it. The sweet scent of jasmine wafts from the jar and Xichen jerks upright. Mingjue grins at his hopeful expression, seeming pleased with himself. Sitting next to Xichen, Mingjue shows him the jar, and Xichen touches the thick cream inside that smells so powerfully of home, of the jasmine bushes that wind through the Cloud Recesses, the bees that form clouds around the flowers, and somehow also like the waterfall that crashes over the mountain.

“How?” Xichen asks, his heart clutched tightly in the memories the scent carries. “How did you know?”

Mingjue touches Xichen’s hair and leans forward to inhale, nuzzling his nose against the skin behind Xichen’s ear. “It is how you smelled when we met. I could never forget.”

Xichen feels broken open and defenseless, and he doesn’t resist when Mingjue begins to rub the cream onto his back. All he can think about it is how he’s rejected calling this love, even in his own mind. He likes Mingjue, he’s foolishly attracted to him, but Xichen is always aware that he has no real choice but to be here. And he can’t ignore what the Ikarahu are doing—have done—can he?

Mingjue reaches his feet, rubbing them one at a time, and Xichen closes his eyes. He has been shown nothing but kindness, treated with nothing but love. No one here has ever raised a hand or voice to him, belittled his opinions, or treated him like an object to be attained. If he had chosen, would he have chosen any differently? Would he choose anyone else? Would he want a life without Mingjue in it?

Before Mingjue can finish, before he can start to dress, Xichen grabs his hand.

“Ahoraho, will you stay tonight? Stay with me?” he implores, trying out the word—beloved one—and it fits perfectly in his mouth.

The radiant smile Mingjue gives him makes Xichen realize he had only been waiting for Xichen to ask.

Mingjue fits himself against Xichen, threading his fingers through Xichen’s under the warm blankets, and he feels safe, and loved, and wanted. Before Xichen falls asleep, with Mingjue’s breath on the back of his neck, Xichen wonders if this is what having a soulmate is like.

Like a hand linked in his.

Like the steady thump of a heartbeat next to his.

Like a gift he did not even know he wanted.

What more could there possibly be?

Translation Notes:

Tiras mau. = My thanks.

Kami teko parau? = Brush your hair?

Ani, aitapaho, iko eko paka. = Yes, treasured one, only for you.

Aitapaho, ek eko mau Sikunadis, my bright heart. Eina katu sima aki akiti eko? Da atem okira auha di teko kiria. = Treasured one, you are my Sikunadis, my bright heart. What did I do to deserve you? I will die happy in your arms.

Ereda sinedi? = Continue?

#the untamed#cql#the untamed fic#soaring au#nielan#nie mingjue#lan xichen#mdzs#nie huaisang#luo qingyang#happy birthday xichen

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jun 17

Saw a post about the sideshow performers Eko and Iko being kidnapped, remembered sideshow/circus history is one of my interests, did some Googling, and have come to the opinion the book makes a point and should I want to get particular about Eko and Iko and/or people of color in the sideshow and circus I will look in to it.

in the circus performer hierarchy, which would have reflected general American culture at the time, all sideshow performers were at the bottom with the clowns, aerialists and animal trainers were at the top, but everyone got fed, housed, and stood in the same pay line.

If you do get in to the Eko and Iko book throw in one that covers the golden age of the circus which they were part of.

For some disabled people being in a sideshow was the only way to support themselves and they were able to use their savings to buy homes.

It’s a complicated thing.

Now get your freaky asses on the train.

Because Dog Face and Torso Lady are welcome to make all the puppies they want, as long as they get married, in a special performance the circus can charge extra for. That would make a great blow off.

And yes, quite a few bearded ladies were men. Alas it was commented the fakes took “better care” of themselves than the “real women”. And there was a run on real bearded ladies, especially after one shaved and became the tattooed lady.

The golden age of the American circus has some great stuff for writers.

On the home front the big mess has finally been properly taken care of. With smaller ones that need doing I’m still stuck doing busy work or something I can put down.

Wanting to move my art instruction books to the shelf with the art stuff.

Feeling my ability to organize is slowly fading.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

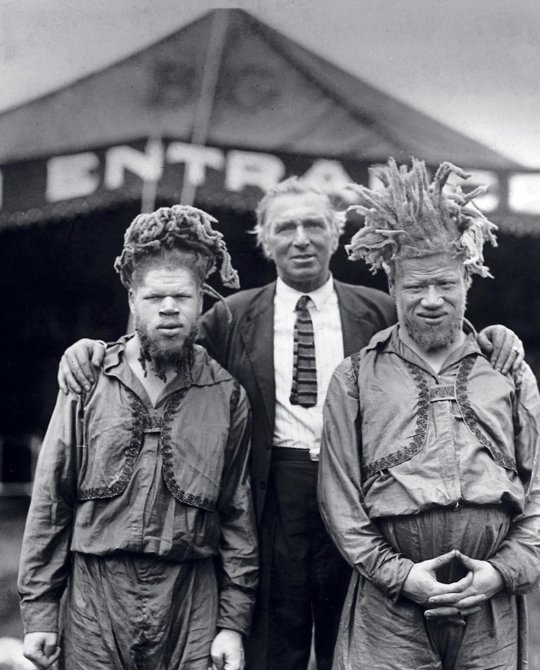

eko e iko, a.k.a. george e willie muse, com um de seus captores, o showman al g. barnes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are the Muse Brothers. Their biological names are George and Willie Muse. They were two albino brothers; the grandsons of former slaves and sons of tobacco sharecroppers born in Roanoke, Virginia, in the 1890’s.

In 1899 George and Willie Muse were kidnapped as boys in Truevine, Virginia by bounty hunters and were forced into the circus, labeled as “freak show” performers. Upon their capture, they were falsely told that their mother was dead and that they would never return home .

Their owners showcased the brothers in circuses where they were exploited for profit in so-called freak shows. The Muse Brothers became famous across the United States as “Eko and Iko”, the “White Ecuadorian Cannibals”, the “Sheep Headed Men”, the “Sheep Headed Cannibals”, the “Ministers from Dahomey” and “Ambassadors from Mars”.

George and Willie were forced to grow their hair into massive “dreadlocks“ which together with their white skin and bluish eyes were exhibited as rarities. They were also billed as “Darwin’s Missing Links” and “Nature’s Greatest Mistakes”. The boys were not permitted to go to school, neither were they paid for their work. They were literally kept in slavery, earning nothing despite thousands of people who paid to see them. Their only rewards were clownish attire they wore for the shows and food meant to keep the ‘assets’ alive.

One of their owners had found that George and Willie harboured the ability to play any song on almost any instrument, from the xylophone to the saxophone and mandolin, and that made them even more famous and more valuable ‘assets’ to owners of travelling circuses. However, after all this time, their illiterate mother had not ceased looking for her boys.

In the fall of 1927, the brothers were on a tour with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus to Roanoke, little did the boys know they were coming home from which they had disappeared nearly three decades back. It came to their mother’s attention that the The Greatest Show On Earth was in town and she was determined to find them. It was a tough decision to confront the Ringling Brothers who were powerful multimillionaires who also had the attention of the heavyweight politicians and law enforcement agencies.

Their mother tracked them down and eventually found the boys working for the Ringling Brothers circus and surprised them while they were on stage and their family reunited, 28 years later since they had gone missing in the very same town. The poor and powerless black woman stood up to police and big shot circus owners and successfully took her sons home.

#BLACKHISTORY

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keren! Seniman Asal Demak, Lukis Soekarno dan KH Maimoen Zoebair dengan Pelepah Pisang

KONTENISLAM.COM - Seniman asal Kabupaten Demak memanfaatkan pelepah pisang menjadi lukisan yang indah. Ia adalah Eko Budiyono, 30, pelukis yang memanfaatkan pelepah pisang. Ia merupakan warga Desa Dukun, Kecamatan Karangtengah, Kabupaten Demak. Dilansir dari Jatengnews.id, Eko mengaku pekerjaan utamanya bukanlah sebagai pengrajin seni, melainkan seorang buruh pabrik di salah satu perusahaan di Demak. “Jadi lukisan ini saya buat untuk tambahan pendapatan saja, bukan sebagai pemasukan utama,” ungkapnya Ketika ditemui di rumahnya Minggu (25/7/2021). Ia bercerita, bakat berseni yang ia miliki memang sudah ada semenjak dahulu masih kecil. Tidak ada latar belakang pendidikan seni yang ia tempuh, karena sampai pada tingkat SMA saja dirinya mengenyam pendidikan. Pada tahun 2009, dirinya juga sudah mencoba membuat beberapa karya seni baik dua dimensi maupun tiga dimensi. “Cuma memang pada waktu itu, saya belum berani untuk menjualnya. Jadi masih sekadar bikin saja,” katanya. Waktu pandemi menghantam Indonesia, Eko juga menjadi salah satu yang terdampak. Ia harus mengundurkan diri karena kondisi keuangan tempatnya bekerja sudah tidak sehat lagi. “Akhirnya untuk menambah pemasukkan, saya berani berjualan karya seni saya ini,” ungkapnya. Untuk saat ini sendiri, Eko mengaku tidak menyetok karya seni terlalu banyak. Dirinya lebih memilih membuat lukisan sesuai dengan pesanan karena warna pelepah pisang yang ia pakai cukup sukar dicari. “Jadi kalau yang saya pakai ini warnanya murni dari pelepah pisangnya, tidak saya buat dengan dikeringkan atau bagaimana. Warnanya bakal awet dan tidak berubah,” ujarnya. Amunisi yang dipakai Eko untuk membuat lukisan pelepah pisang sendiri cukup sederhana. Hanya pelepah pisang, gunting, lem, dan triplek sebagai dasarnya. “Jadi kalau proses pembuatannya saya pilih-pilih dulu pelepah pisang yang cocok. Satu hal yang penting untuk membuat detail wajah kan gelap terangnya. Setelah begitu saya buat gambar dasarnya di triplek, kemudian saya buat wajahnya itu ibarat membuat puzzle, jadi menyesuaikan bagaimana biar wajahnya itu sesuai dengan yang asli,” jelasnya. Untuk saat ini, pangsa pasar pelanggan milik Eko sendiri masih belum terlalu luas. Pembeli masih baru dari sekitar Kabupaten Demak. Cara ia mempromosikan karya seni ciptaannya juga masih terbatas menggunakan akun Facebooknya saja. “Saya belum pakai marketplace seperti Shopee atau bagaimana, soalnya tidak tahu caranya,” katanya. Dalam upaya mempromosikan karya seninya, Eko mengunggah juga ciptaannya di grup pecinta seni di Facebook. Satu unggahan milik Eko bisa disukai sampai delapan ribu orang dan banyak pesan masuk yang menanyakan harga lukisan pelepah pisang miliknya. “Cuma memang terkadang itu sekadar bertanya, kemudian setelah tau harganya tidak memberi kabar lagi. Memang sudah biasa seperti itu,” ujarnya. Untuk karya seni ciptaannya, Eko mematok harga mulai dari Rp150 ribu. Hal ini tergantung kerumitan dan dimensi dari lukisan yang ia buat. Lebih lanjut ia mengatakan proses pembuatan bisa mencapai dua hari karena ia buat di sela-sela waktu bekerja. “Walaupun sudah tidak terlalu mahal begitu ya masih saja ada yang menawar cuma Rp50 ribu,” ungkapnya. Meski kali ini dirinya berfokus membuat karya seni lukisan pelepah pisang, Eko mengaku bisa membuat karya seni lain seperti kapal yang menggunakan bahan dasar batang es krim maupun lukisan dengan media yang lain. Untuk saat ini lukisan pelepah pisang yang tersedia di rumah milik Eko ada tiga. Satu berwajah Presiden Republik Indonesia Pertama, Ir. Soekarno dan dua lainnya memamerkan wajah mendiang sosok pemuka agama kharismatik, KH. Maimoen Zoebair dan KH Hasyim Asy’ari. Meski begitu, tak terbatas melukis wajah, dirinya juga bisa melukis kuda, Ka’bah, bahkan kaligrafi menggunakan bahan pelepah pisang. “Untuk yang ukuran 50×70 sentimeter itu harganya Rp200 ribu, masih belum dengan figuranya. Kalau pakai figura beda lagi harganya,” ungkapnya. Untuk melihat karya seni buatan Eko sendiri masyarakat bisa melihat akun Facebook Iko Tama. Ia bisa membuat lukisan wajah sesuai dengan pesanan. Dirinya bisa dihubungi melalui nomor WhatsApp 08988398369.(suara)

from Konten Islam https://ift.tt/3zzh9pl via IFTTT source https://www.ayojalanterus.com/2021/07/keren-seniman-asal-demak-lukis-soekarno.html

0 notes

Photo

George and Willie Muse. Originally born in Truevine, Frqnklin County, Virginia, the albino grandsons of former slaves, they were just children when a white man , termed a bounty hunter for traveling circuses, aka,, freak shows, lured them from the tobacco field they were working in, with a piece of candy. Sold to the Ringling Brothers and P.T.Barnum Circus- yes, 'The Greatest Show on Earth, they were given the names Eko and Iko. For 13 years, their mother Harriet waited for them to come home, moving from Truevine to Roanoke. VA- long vanished Jordan's Alley in the West End. She finally got her wish in 1927, when the circus rolled into Roanoke. But it wasn't easy, they had money, lots of it and she was a poor working woman. In 1928, it appears that the brothers went back to the circus, their mother having won not only backpay, but a contract and wages- that was still skimmed by the circus- for them. They sent her money out of those wages, that allowed her to buy a small farmhouse to live out her days. Harriet passed of a heart attack in 1942 and was buried in an unmarked grave in a then segregated cemetery. The brothers returned for her funeral. Willie Muse lived to be 108 years old. George Muse died in 1971. Their descendants live in Roanoke and surrounds, to this day. #nofilter #blackhistorymatters #blackhistory #blacklivesmatter #georgeandwilliemuse #p.t.barnumwasracist #thegreatestshowonearthwasnt #blackhistoryweshouldknow #persistandresist #blm #dantesspirit https://www.instagram.com/p/CDZXOjOpMCv/?igshid=1plhmey0y2q4t

#nofilter#blackhistorymatters#blackhistory#blacklivesmatter#georgeandwilliemuse#p#thegreatestshowonearthwasnt#blackhistoryweshouldknow#persistandresist#blm#dantesspirit

0 notes

Text

Eko and Iko movie sounds right.

Harriet Muse, right, and husband, Cabell, far left, with the brothers shortly after she found them at a sideshow in 1927. Photograph by George Davis. The brothers were kidnapped from their home in Virginia to become circus performers. ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

“Black children reared during the postwar baby boom rarely left home without being admonished by their mothers, “y’all stay together now or you might be kidnapped, just like Eko and Iko.” Eko and Iko were the sideshow names of George and Willie Muse, the grandsons of former slaves.” written by Beth Macy for the Washingtonian in 2016.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

soaring, carried aloft on the wind...continued 9

A story for Xichen and Mingjue, in another time and another place.

The Beifeng, the mighty empire of the north, invaded more than a year ago, moving inexorably south and east.

In order to buy peace, the chief of the Lan clan has given the Beifeng warlord a gift, his second oldest son in marriage. However, when Xichen finds out he makes a plan.

He, too, can give a gift to the Beifeng warlord, and he will not regret it.

Part 1: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 8 / 9 … HOME

It’s on AO3 here if that’s easier to read.

NOTES: This story starts out G but will eventually be E for Explicit. (warning in this chapter for reference to prior attempted assault)

For translations of the entirely fictitious Beifeng language, you’ll have to scroll to notes. I’m only going to translate something that’s not clear in the text. Sadly, there’s just not any other good way to do it on Tumblr!

Chapter 9

Qingyang doesn’t come to Xichen’s tent in the morning for lessons, and Xichen only waits for the time it takes to play Tranquility once before he goes to find her.

If it was Huaisang, he wouldn’t be concerned, but Qingyang is always prompt. He considers the possibilities. Even though she spends so much of her day with him, she is still a cartographer, so it’s possible she merely forgot to tell him she would be working on something else. But this is a war. This is an army. He can’t help but worry.

His first thought is to check the command center, where he assumes Huaisang and Mingjue are. But he’s never been, and it’s next to Mingjue’s tent. If he has to ask directions....

No, it makes more sense to go to the tent Qingyang’s shares with some of the other single women in the area of the camp designated for non-military officials. He has, at least, been there once, and if she isn’t there, then he can consider looking for her somewhere else. The commissary perhaps?

He isn’t nervous to see Mingjue, he tells himself, walking through the organized city of tents. He is being logical.

Xichen hesitates on the threshold of the tent he knows is Qingyang’s from the yellow and white peonies painted around the door. It seems intrusive to barge in, but he hears a noise from inside, something close to a sob, and he peeks in, noting the sparse accommodations in this tent. Each woman has a bedroll—thick, but still directly on the ground—and a small trunk, presumably with personal belongings. It makes sense for an army to live lightly, but it makes him wish his own space was a little less ostentatious. What must Qingyang think of him?

He sees her immediately, the source of the sound that had caught his attention. He has grown so accustomed to Qingyang’s cheerful resilience, it is a shock to see her hunched on the edge of her bed, face in her hands, crying.

“Qingyang?” he asks, and she jolts, shooting to her feet and wiping away the tears.

“Xichen, I’m sorry, I’m late. I...I’m fine. Just homesick, I guess,” she stammers, forcing a smile onto her face.

He accepts the lie. If she doesn’t want to tell him, he’s not going to ask. He has already overstepped more than he should have.

“No apology necessary. I was worried for you. Will you come with me and have breakfast? Perhaps we can even track down something more palatable than Beifeng tea,” he tries to joke, and she laughs, thin and wispy, but since she’s making the effort, he chuckles too.

She nods and grabs a long cotton shawl, woven in a bright stripes as the Beifeng women wear. They walk through the rows quietly. Qingyang seems lost in thought, and Xichen doesn’t want to interrupt. Instead, he tucks an arm behind his back and observes the tents they pass.

The encampment is organized into companies, and each company is arranged around a small common area that has at least a fire pit, but many of them have logs to sit on, cooking pots, huge wash tubs, even the occasional tethered horse. The tents are identical, but some of them have personal touches: lanterns over entryways, strings of bells tinkling in the breeze, drawings of horses and birds, mountains and trees around the tent flaps. The army has been here nearly a year, he thinks. Long enough to yearn for home.

Qingyang stiffens and stops, wrapping her shawl more tightly around her body.

“Not that way,” she hisses, and Xichen turns in the direction she is staring.

There is a tall man standing at the end of a row of tents watching them. Watching Qingyang. Xichen knows very few of the Beifeng soldiers by sight—only the guards at his door and a few he’s seen at the hospital. He knows some of the healers, some of the kitchen staff, and the woman who cleans his tent. He has never seen this man. He’s sure he’d remember him. His face looks sculpted by a rough chisel and a hurried artist, distinct and somewhat disquieting. When the man catches sight of Xichen, his expression turns flat and cold.

A warning prickles the back of his neck, and he doesn’t blame Qingyang for wanting to avoid this person. They turn down another row, both hurrying their pace.

“Hewnta!” the man’s deep voice calls from behind him. “Etan Hewnta, iko om touha?

Xichen turns. The man is right on their heels. Xichen doesn’t know the word “Hewnta,” but the man warps it into something spiteful, and he doesn’t need the exact translation to know it’s an insult.

“Dei. Em ereda anha outam,” he says firmly, putting himself between the approaching threat and Qingyang.

Xichen expects the tall man to back down. In only a few scant weeks, he’s grown accustomed to the Beifeng treating him with deference, sometimes even fear. He disliked the implication at first, but there didn’t seem to be anything he could do about it.

He doesn’t expect the man to argue. He definitely doesn’t expect three other people, a woman and two men, to step into the row with the tall man.

Roka ta em ereda kei dikas,” the tall man snarls. “Roka eko em ereda kei dikas hako, egadi.”

It’s easy enough for Xichen to recognize that he’s being cursed without knowing exactly how, but the man looks past him, pointing, aiming his cruelty at Qingyang. She bites her lip and looks away from Xichen, as though hiding the injury means it doesn’t hurt, and there’s too much it reminds him of, too much reflection of his brother in her eyes for Xichen to walk away.

Xichen narrows his eyes and holds up his hand. “Dei,” he repeats. “Ereda irumaka.”

The man roars with laughter, and Xichen is done placating. He grasps the hand still raised toward Qingyang and pushes just enough of his power into the tall man to force him to one knee. The man’s laughter breaks off, replaced with rage, but he stays down.

“Xichen, stop. I don’t care. Damias is always an ass.”

Qingyang tugs his sleeve, and Xichen reluctantly pulls back. A part of him would very much like to hurt this Damias a little more for the tears on Qingyang’s face, but Qingyang is right. It’s better to go.

As soon as he turns away, he hears it. There’s no mistaking the sound of a sword being drawn. Xichen has just enough time to meet Qingyang’s eyes and wordlessly apologize. She didn’t want a confrontation and now there will be one.

Xichen opens his awareness to feel the sword moving through the air, and he ducks in time for it to easily sail over his head. The man is a skilled warrior, though, and recovers almost immediately, pivoting in the narrow space between two tents and sweeping back at Xichen. This time, Damias doesn’t make the same mistake and swings low, twisting at the waist and planting his feet to put more power behind his strike. Xichen sidesteps and kicks his wrist.

It should have sent the blade flying, or at the very least, driven the man’s arm up into the air. It should have ended this stupid, useless fight.

But the man is stronger than Xichen anticipated, and he controls the sword just enough to keep it in his hand.

But Xichen didn’t realize Qingyang had stepped behind him, maybe to stop him, maybe to get out of the way.

But he sees Qingyang too late, only in time to see the sword slash into her, and she falls.

His first instinct is terror for his friend. Slowly, the memory of what he saw solidifies in his mind. He realizes that the sword missed her torso entirely, and the staining blood is from a slice across her leg. Even more slowly, as though the world has paused to give him a chance to perceive the entire scene at once, he sees Damias grin and cock his right arm back, the fingers of his other hand crooking to grasp the Beifeng magic, and Xichen knows he can not let him continue.

He grabs the man’s neck, the only exposed part of his body, and pours all the magic he can muster into him. Xichen has only felt this once, for the merest fraction of a second when his father was teaching him how to use the gift that lives inside him, but he knows it feels like burning alive from the inside out. Damias screams as the full inferno of Xichen’s power tears through him. Xichen lets go almost immediately—he only wants to stop Damias, not kill him—and the man drops to his hands and knees retching, the sword finally falling from his hand.

Xichen looks at the man’s friends running toward him and holds up a hand. The woman skids to a stop, her face a mask of fright and she drops to the ground in supplication, but the other two—

The other two don’t have time to stop.

A black wave of Beifeng magic flows over them, thicker than Xichen has ever seen, the curling smoke arresting their movements like ants drowning in a drop of tree sap. They both scrabble desperate hands at their throats and Xichen realizes the magic is inside them, choking the air from their lungs.

He whirls.

This is the Mingjue he expected when he came to the Beifeng. This Mingjue striding toward him is the pitiless warlord, his eyes too dark to read, his fingers curled around the cloud of magic still holding the soldiers tightly. This Mingjue’s sword is drawn and raised, and he looks fully intent on using it. This Mingjue looks like the demon everyone fears, who came from the mountains and cut a bloody path through Xichen’s country.

Xichen’s gut lurches sideways, and an errant thought—what would he look like with his hair down—wanders through his mind.

But when Mingjue reaches Xichen, his expression shifts from tight-lipped outrage to something that almost looks like fear, and his eyes search Xichen’s face and form, as if looking for something. Xichen realizes that it must have looked like he was being attacked by the soldiers, and a terrible, disgraceful shard of his heart exults in being the one who is defended, the one someone else protects.

Damias groans, and Mingjue’s attention shifts, a predator to prey. His arm raises slightly and Xichen is suddenly afraid for these people. They did a foolish thing, but they don’t deserve to die for it. He wants to stop Mingjue, but he doesn’t have the words to explain, and he needs to help Qingyang.

“Anakau, peimi!”

Xichen has never been so relieved to see Huaisang.

“Ahora’ipa, ka marai ota eko?” Mingjue growls, ignoring Huaisang.

“Ekos, Ipira’orhew Ikira,” Xichen answers. Luckily, “no” is one of the first words he learned.

Mingjue frowns, but he lowers his sword. He doesn’t release the magic, but it seems to ease, the nearly opaque cloud fading to smoke. The woman doesn’t get up, but she starts speaking in rapid Orera, obviously pleading. Pleading for her life, Xichen suspects.

“What happened?” Huaisang asks Xichen urgently, but Xichen pushes past him to get to Qingyang.

“Qingyang, I am so sorry. This is my fault,” Xichen says, kneeling next to her. She’s wearing wide-legged pants, and he shoves them up to her thigh, heedless of propriety. He moves her hand and touches her bloody leg. The injury is a long crease cut across the top of her leg. He wants to cry. He keeps making mistakes, and he doesn’t want to get anyone else hurt.

She smiles wanly at him. “I’m fine.”

He disagrees. The flow of blood has slowed, but she’s still bleeding. He draws a healing line across the wound, trying to make it painless but shaken at how deeply it goes into her muscle. It could have been so much worse. There are life-sustaining vessels in the legs. If the sword had pierced one…

“Xichen, truly, I’m fine,” she repeats, and Xichen realizes he is crying, dripping tears onto her knee. “You can leave the scar if you want,” she tells him. “Girls love scars.”

His laughter is hoarse and shaky, but it’s laughter. She grins at him.

“You need to tell me what happened,” Huaisang repeats, the urgency in his voice catching Xichen’s attention. “Did they attack you?”

It is Qingyang who answers. “Yes. Earlier, Damias tried...well, it doesn’t matter, because he wasn’t successful. He was angry because I’m only half Beifeng. It was just a mistake that we ran into them here, but Damias drew his sword and tried to attack Xichen. The others…” She pauses and frowns. “I don’t know. They didn’t do anything. Maybe they would have tried to stop him.”

“And this?” Huaisang asks, gesturing to her leg.

“This was my fault,” Xichen repeats gloomily.

“This was an accident, Xichen,” Qingyang sighs, sounding irritated.

“Take Qingyang back to your tent now,” Huaisang tells him quietly, not as calm as he appears. “We’ll deal with this.”

Mingjue releases the magic suddenly, and Xichen can feel the relief in the air, like a sudden rain that breaks the humidity of summer or the biting wind of winter giving way to spring. Mingjue shouts something furious, and the woman somehow shrinks further into the ground. The two men are now gasping to breathe, and one of them sags to the ground with the woman, but the other is apparently too slow. Without warning, Mingjue punches him in the jaw, and the man drops like a bucket into a well. Mingjue gestures at the other two people, making it clear that the man should have thought of this himself. He seems angry, yes, but Xichen thinks he also looks profoundly disappointed, and he pauses, wanting—what? To say something soothing? What can he say?

“Xichen, go,” Huaisang says, the tension in his voice prodding Xichen to obey. “I’ll come talk to you later.”

He’s worn out from the healing and from stopping Damias, but Xichen lifts Qingyang and carries her back to his tent, where he insists that she sleep on his bed. She looks like she plans to be stubborn about it, so he brushes a hand across her forehead to push a little bit more warmth into her and make the sleep a little bit more imperative, then sits on a cushion to wait for Huaisang.

Xichen wakes without ever having realized he’d fallen asleep to the sound of raised voices outside his tent. It sends a spike of fear through him before he recognizes them. They get louder, and he’s afraid they’ll wake Qingyang. He pads to the tent flap.

As he expected, Huaisang is yelling, and Mingjue is glowering, arms crossed.

“Huaisang, shhhh. Qingyang is sleeping,” Xichen says, and they both jump.

Huaisang looks instantly contrite. “I’m sorry, I was just saying that.” He glares at Mingjue, the I told you so obvious. “We should be going.”

He pulls Mingjue’s arm, but Mingjue shakes him off and takes a step toward Xichen before he seems to catch himself, hands clenching into fists. Instead of moving closer, he says Xichen’s name like it’s a question, searching Xichen’s expression for an answer.

The answer, Xichen thinks, depends on the exact question, but he thinks Mingjue might be surprised. Xichen isn’t shocked to see the kind of power and violence Mingjue is capable of. This is an army. This is war. It was no more than Xichen had done. Less, even. He looks into Mingjue’s eyes, eyes that look red and bloodshot from unshed or maybe even shed tears, and he thinks Mingjue must have believed he had no choice but to harm his own people for Xichen and Qingyang. And Xichen thinks perhaps he is the more ruthless man, because he would shed no tears to hurt Damias again for whatever he did to make Qingyang cry.

He wishes he had the right words to explain.

Mingjue reaches for Xichen as though he can’t stop himself, but Huaisang interrupts.

“Xichen, tell Qingyang that Damias has been demoted, branded, and sent home without a horse. He won’t bother her again. The others have only been demoted, but they have been strictly ordered to leave you both alone. I’m sorry this happened. It’s not...it’s not how most people think.”

Xichen nods and hesitates before going back inside. Why, he asks himself, is he hesitating?

But he knows why.

Stepping forward, he slips one arm around Mingjue’s waist and rests the other on his chest, above the steady beat of his heart. Stretching, he kisses Mingjue on the cheek. Tiny sparks flit over his chin, his lips, his nose—all the places that graze Mingjue’s skin. The world doesn’t stop spinning, but a breathless part of him wishes it would give him just a little longer to stay here.

“Thank you for being there. Tiras mau,” Xichen says softly, for only Mingjue to hear.

Mingjue closes his eyes and inhales as though it is the answer he was looking for, the only answer he needs. He covers Xichen’s hand on his chest and squeezes, touching his forehead to Xichen’s, a simple gesture that has no right to feel as shockingly intimate as it does. It puts words in Xichen’s mouth that he has to bite back—will you stay, will you come inside, will you kiss me again? Qingyang is still sleeping on his bed. Perhaps it’s for the best. He steps away, and Mingjue’s fingers trail over Xichen’s palm as he finally lets Huaisang pull him away.

Xichen watches them go as something loudly and firmly locks inside his heart.

Notes:

Hewnta! Etan Hewnta, iko om touha? = [Insulting word for person who speaks Yuyan]! Hewnta woman, back for more?

Dei. Em ereda anha outam. = Stop. We’re leaving.

Roka ta em ereda kei dikas. Roka eko em ereda kei dikas hako, egadi. = She doesn’t belong here. You don’t belong here either, [insult for weak man].

Dei. Ereda irumaka. = Stop. Go away.

Anakau, peimi! = Elder brother, wait!

Ahora’ipa, ka marai ota eko? = Ahora’ipa, have they hurt you?

#the untamed#cql#mdzs#soaring au#nielan#nie mingjue#lan xichen#mo dao zu shi#nie huaisang#luo qingyang#the untamed fic

5 notes

·

View notes