#Eudibamus cursoris

Text

I drew tons of dinosaurs for…something. This is one example. Eudibamus cursoris!

0 notes

Text

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part VII: Eudibamus cursoris, the Original Two-legged Runner

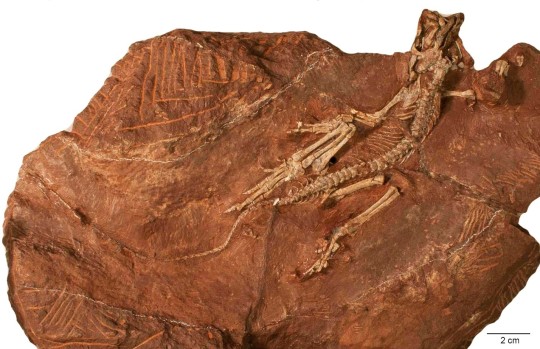

Holotype specimen of Eudibamus cursoris, the most complete bolosaurid reptile known. Photo by the author, 2013.

Stuart Sumida discovered some small bones in the Bromacker quarry in 1993, the same year that the holotype skeleton of Diadectes absitus was found. Dave Berman told me that when Stuart showed them to him, he couldn’t see anything because they were so small. Upon closer examination, Dave, Stuart, and Thomas Martens identified them as those of the captorhinomorph reptile Thuringothyris mahlendorffae. Thomas’ wife Stefani, whose maiden name is Mahlendorff, discovered the first specimen in the Bromacker in 1982, and Thomas and a colleague named it in her honor in a 1991 publication.

The fossil was exposed in several pieces of rock, which Thomas shipped to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) along with the large block of rock containing Diadectes. I didn’t prepare the specimen until several years later, as other projects, including the Diadectes, overshadowed it. Once I began working on it, though, Dave and I realized that it was not Thuringothyris. Indeed, we had no idea what type of animal it was, and our puzzlement grew as I exposed more of it. The identity wasn’t revealed until I had uncovered some very unusual, tiny teeth, which under the high magnification of the preparation microscope appeared to have a bulbous cusp towering over a basin. They looked vaguely familiar to me, but because I couldn’t immediately put a name on them, I rushed to get Dave from his office. Once Dave saw the teeth, he realized that the specimen was a new genus and species in the rare, enigmatic reptile group Bolosauridae.

Tiny teeth of a bolosaurid reptile, Bolosaurus striatus, in lateral (side; left) and occlusal (chewing surface; right) views. The specimen is in the CMNH Vertebrate Paleontology collection. Photos by Spencer Lucas (Research Associate, CMNH).

Until the discovery of Eudibamus cursoris, bolosaurids were represented in the fossil record by two genera, Bolosaurus and Belebey, which were based mainly on poorly preserved skull and fragmentary jaw fossils from Texas and Russia, respectively. Even though bolosaurids had been known since 1878, their relationship to other reptiles was not well understood. The nearly complete anatomy of Eudibamus allowed our team to determine that bolosaurids are the oldest member of the ancient group of reptiles called Parareptilia. This group has no living relatives, except possibly for turtles, a hypothesis that is highly debated by scientists.

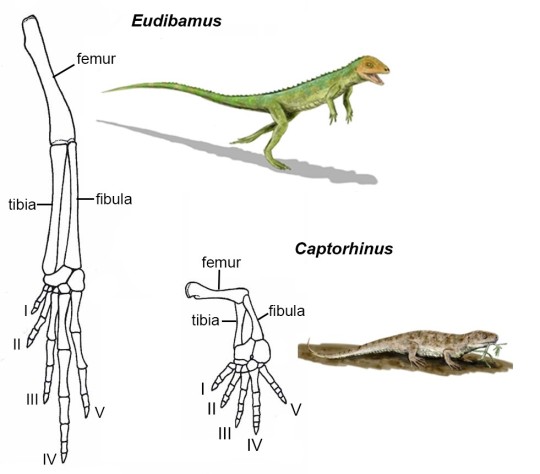

Closeup of front and hind legs of Eudibamus. The hind leg, folded upon itself, is considerably longer than the front leg. Photo by the author, 2013.

When our study of the fossil began, we realized that Eudibamus was very different than other reptiles from that time. Proportions of the limbs and positions of the articulation surfaces on the upper and lower hind leg bones indicated that, in terms of posture, Eudibamus resembled a bow-legged human with a bad back instead of a typical sprawling reptile on four legs. It could stand and locomote on its hind legs in an upright posture (bipedal) with its legs held close together and in the same plane (parasagittal).

Dave was in constant phone communication with team member Dr. Robert Reisz (Professor, University of Toronto at Mississauga). One day Robert called Dave to ask if all the tail had been exposed, because he learned that modern lizards that are able to run bipedally have a long tail to help maintain their balance. The specimen was in Dave’s office and he immediately uncovered more of the tail and then let me finish the task. The tail was indeed very long and extended close to the edge of the block, which I had previously reduced in size. Additionally, we determined that the third, fourth, and fifth toes of the hind foot also were greatly elongated through lengthening of some of the individual toe bones, and that the first and second toes were extremely shortened by the reduction in size of individual toe bones. We hypothesized that when Eudibamus ran bipedally, it would rise on its toes, so that only the tips of the third, fourth, and fifth toes would contact the ground.

Drawing of the hind leg of Eudibamus cursoris (left) and the roughly contemporaneous reptile Captorhinus (right). Leg drawings are scaled to the same torso length of the whole animal. Illustrations of the animals are not to scale. Hind leg drawings are modified from Berman et al., 2000 and animal illustrations are from Wikimedia Commons.

Eudibamus occurred at least 60 million years before other bipedal, parasagittally-running reptiles appeared in the fossil record. This is reflected in its scientific name, which is derived from the Greek “eu,” meaning original or primitive, and “dibamos,” meaning on two legs. “Cursoris” is Latin, meaning runner. Examples of other reptiles using this locomotion mode are the dinosaurs Allosaurus fragilis and Tyrannosaurus rex, which you can view in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition.

So, what was the advantage of being able to run bipedally instead of running on all four legs? Lengthening the hind leg and foot would greatly increase stride length, especially if only the tips of the toes contacted the ground, which is an efficient way to increase speed. Eliminating arm to ground contact while running removes forelimbs from the path of the long-striding hind legs. The bulbous teeth and jaw structure of Eudibamusindicate that it was herbivorous. It seems likely, then, that Eudibamus used its ability to sprint to avoid becoming a tasty meal for a pursuing predator.

Peter Mildner (exhibit preparator at the Museum der Natur, Gotha) made a surprise visit to the Bromacker one afternoon to show us a model of Eudibamus cursoris he’d made. This image shows the model in the present day Bromacker quarry, part of the region it inhabited 290 million years ago. Photo by the author, 2006.

One of our laments is that a fossil trackway preserving Eudibamus walking quadrupedally and then switching to a bipedal gait has yet to be found.

Next time you are at CMNH, make sure you see the cast of the fossil skeleton and a model of Eudibamus that are exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Stay tuned for my next post, which will feature the herbivorous mammal-like reptile Martensius bromackerensis.

For those of you who would like to learn more about Eudibamus, here is a link to the 2000 Science publication in which it was described: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/290/5493/969.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Eudibamus cursoris#Reptiles#Fossils#Vertebrate Paleontology#Bromacker Fossil Project#Natural History

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eudibamus cursoris, a bolosaurid from the Early Permian of Germany (~284-279 mya).

Although very lizard-like in appearance, this animal was actually part of a completely extinct group known as parareptiles -- a diverse group of early sauropsids who were once thought to be the ancestors of turtles, but are now considered to instead be the evolutionary cousins to the true reptiles.

With a total length of about 25cm long (8-10″), the structure and proportions of its limbs suggest it could run fast on its hind legs, making it one of the earliest known examples of bipedal locomotion. Since its teeth were adapted for a herbivorous diet, it wasn’t using its speed to chase down prey but was instead probably sprinting away from predators.

But unlike the sprawling running of some modern lizards, Eudibamus may have been capable of holding its legs in a more upright position directly under its body, convergently evolving a more energy-efficient posture similar to that of later bipedal animals like dinosaurs.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#eudibamus#bolosauridae#procolophonomorpha#parareptilia#art#bipedal#running#gotta go fast

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bromacker Project Part VI: Seymouria sanjuanensis, the Tambach Lovers

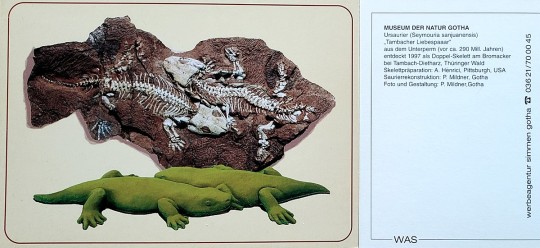

Two exquisitely preserved, nearly complete adult skeletons of Seymouria sanjuanensis that were discovered in the Bromacker quarry in 1997. Photo by Dave Berman.

At lunchtime on the last day of the 1997 field season, Thomas Martens discovered the two exquiste specimens shown above, the only fossils found that year. Thomas had uncovered a piece of the hip region with some attached vertebrae that resembled, once again, those of the ancient amphibian Seymouria. Because our work time was limited, we estimated the length of the specimen and rushed to extract it from the quarry. When we flipped the block over, a few pieces of rock fell out, revealing a series of vertebrae of a second individual in the block. We were thrilled to learn that Thomas had discovered two specimens of Seymouria. We put the rock pieces back in place and quickly finished plastering the block. There was just enough time for Dave, Stuart Sumida, and I to return to our hotel, clean up, quickly pack, and meet Thomas, his family, and his fossil preparator Georg Sommer for a celebratory dinner. What a great way to end the field season.

Working in tight quarters to quickly extract the Seymouria specimens discovered at lunchtime on the last day of the field season. Clockwise from right: Georg Sommer, Dave Berman, and the author. Photo by Stuart Sumida, 1997.

Seymouria had already been known from the Bromacker quarry. Thomas had discovered and identified two skulls in 1985, fossils he brought with him when he came to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) in 1993 to study for six months with Dave Berman under a CMNH-financed fellowship. Both skulls were of juvenile individuals. Of the two known species of Seymouria, Dave and Thomas were excited to discover that the Bromacker skulls were nearly identical to those of Seymouria sanjuanensis. The 1997 lunchtime discovery of the two complete adult specimens confirmed the identification of the Bromacker Seymouria as S. sanjuanensis.

The first discovered species of Seymouria was Seymouria baylorensis, from near Seymour, Baylor County, Texas, from which its name was derived. Seymouria sanjuanensis was first found in San Juan County, Utah, by Dave Berman and the field team he was leading as a graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dave’s advisor, Dr. Peter Vaughn, named it Seymouria sanjuanensis in reference to the county of discovery. Another discovery of five specimens of this species preserved together was made by Dave in New Mexico in 1982.

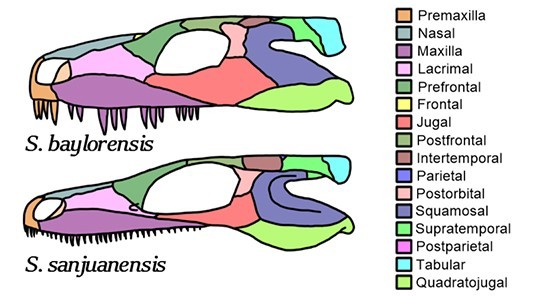

Comparison of the skulls of Seymouria baylorensis (top) and S. sanjuanensis (bottom). The individual bones of the skull are color coded. Skulls scaled to same size. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Seymouria baylorensis is geologically younger than S. sanjuanensis and has a more robust skull, larger and fewer teeth of variable size, and a subrectangular postorbital bone compared to the chevron-shaped postorbital of S. sanjuanensis.

Seymouria is considered a terrestrial amphibian that only returned to water to breed. Its strongly built skeleton provided the support needed to move on land. With its numerous, slender, pointed teeth, S. sanjuanensis most likely ate insects and small land-living vertebrates. We know that the Bromacker Seymouria didn’t consume fish, because not a single fish fossil, scrap of fish fossil, or fish coprolite (fossil poop) has ever been found at the Bromacker quarry. Study of the rock deposits preserving the fossils at the Bromacker indicate a lack of permanent water, which would explain the absence of fish.

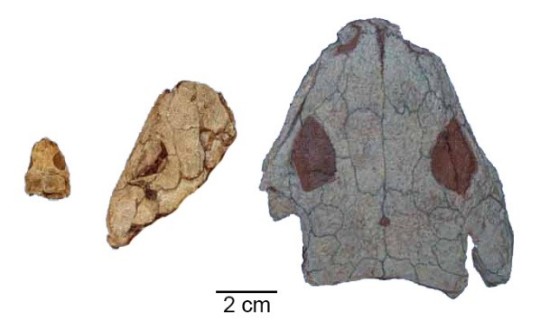

Growth series of skulls of Seymouria sanjuanensis from the Bromacker Quarry showing (left to right) early juvenile, late juvenile, and adult growth stages. Photos by the author, 2006.

Conditions for breeding must have been favorable in the Tambach Basin, the ancient basin where sediments preserving the Bromacker fossils accumulated, because several juvenile specimens of Seymouria are known. The smallest is a skull measuring about 3/4 of an inch long. In a study led by our colleague Josef Klembara (Comenius University, Slovak Republic), we determined that the smallest individual was post-metamorphic—in other words, no longer a tadpole—based on the presence of certain ossified bones in the skull. In tadpoles, these skull elements are cartilaginous; that is, they haven’t yet turned to bone.

Five skeletons of Seymouria sanjuanensis preserved together were discovered in north central New Mexico by Dave Berman in 1982. These specimens are on display in CMNH’s Benedum Hall of Geology, in the “What is a Fossil?” case. Photo by the author, 2013.

The discovery in Germany of the same species of Seymouria previously known only from New Mexico and Utah has important implications in terms of paleobiogeography (the study of the distribution of species in space and time). At the time S. sanjuanensis was alive, the continents were merged to form the supercontinent Pangaea. The presence of S. sanjuanensis across Pangaea, north of a roughly east-west trending mountain range, indicates that climatic or physical barriers (e.g., deserts, inland seas, mountain ranges) didn’t prevent its dispersal.

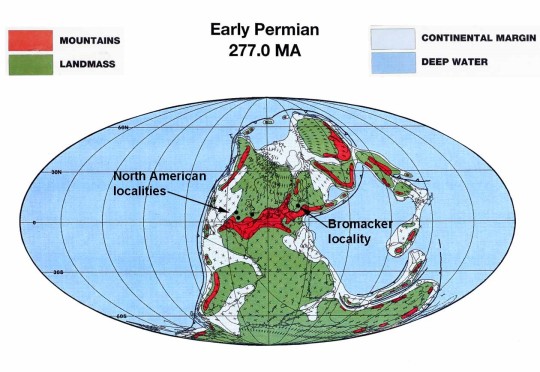

Map showing the arrangements of the continents in the Early Permian. The locality where Seymouria occurs in present-day New Mexico, Texas, and Utah and the Bromacker locality in present-day Germany are indicated. Map modified from Scotese, 1987.

The two Seymouria specimens preserved together were a big hit in the local region in Germany. Museum der Natur (MNG) exhibit preparator Peter Mildner nicknamed them the “Tambacher Liebespaar” (“Tambach Lovers”) after a painting entitled “Gothaer Liebespaar” (“Gotha Lovers”) on exhibit in the Herzogliches Museum of the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein (also the parent organization of MNG). This name caught on and is fondly used by our German friends and colleagues. Peter even made a fleshed-out model of the two Seymouria specimens in their death pose. The proprietor of the hotel in which we stayed hung a copy of the model of the Tambach Lovers and a framed collage of newspaper articles featuring the Bromacker on a wall in one of the hotel rooms, which she named the “Präparation Suite” (i.e. “Preparation Suite” in reference to the preparation of fossils). I often stayed in this room.

The painting entitled “Gothaer Liebespaar” (“Gotha Lovers”), which is on display at Herzogliches Museum of the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha, Germany. Image from Wikimedia Commons and provided by Thomas Martens.

Postcard showing the Tambach Lovers. The postcard was made for and sold by the Museum der Natur, Gotha. Photo of the postcard by the author, 2020.

Stuart Sumida (left) and Heike Scheffel, proprietor of the Hotel Wanderslaben where we stayed (right), with the model of the Tambach Lovers in the “Präparation Suite.” The framed collage to the right of the model holds newspaper articles featuring the Bromacker project. Photo by the author, 2003.

A cast of the Tambach Lovers specimen and a model of Seymouria sanjuanensis are exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Be sure to look for them once the museum re-opens. And stay tuned for my next post, which will feature the unusual bipedal reptile Eudibamus cursoris.

For those of you who would like to learn more about Seymouria sanjuanensis, here is a link to the publication describing the 1997 specimens: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020%5B0253%3AROSSSF%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Bromacker Quarry#Seymouria sanjuanensis#Fossils#Paleontology#Vertebrate Paleontology

34 notes

·

View notes