#Federal Worker's Compensation Blue Springs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

When it comes to safeguarding federal employees who get sick or injured while working, Federal Worker's Compensation offers significant advantages. For work-related illnesses or injuries, this program, run by the Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP), guarantees that federal employees receive the proper medical attention and compensation. We'll look at the kinds of injuries covered by Federal Workers' Compensation in this blog. If you need any treatment for your work injury or need help with the paperwork of Federal Worker's Compensation Blue Springs, contact Core Medical Center, USA, today.

#Federal Worker's Compensation#Federal Worker's Compensation Blue Springs#Motor Vehicle Accident Injuries Compensation#Blue Springs#USA

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

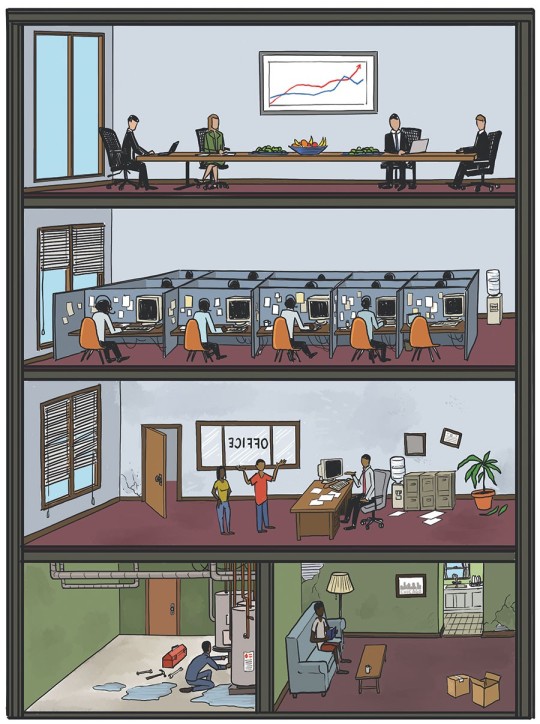

In September the Reader was alerted to two complaints, one filed with the city's Commission on Human Relations and the other with the Illinois Department of Human Rights, detailing discrimination and racist statements made by high-level managers at Pangea, one of Chicago's biggest corporate landlords. Until the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the company was the city's most prolific filer of eviction cases. Its apartment holdings are concentrated largely in Black neighborhoods on the south and west sides of the city and in nearby suburbs, now totaling 9,400 units in 492 buildings. The company also has several thousand more units in Indianapolis and Baltimore.

The complaints were filed by Armando Magana, 45, the chief maintenance supervisor at Pangea in Chicago who'd been with the company since 2010. He's worked in various roles and received promotions and bonuses, most recently in February, Magana writes. "Notwithstanding my exceptional performance, Pangea has repeatedly discriminated against me because of my Hispanic ethnicity and my Mexican national origin. Throughout my employment, Pangea has also subjected me to a hostile work environment based on numerous derisive and derogatory statements made by Pangea's managers and executives regarding my ethnicity and national origin."

Magana's complaint includes several examples of such statements from vice president of operations Derek Reich and CEO Pete Martay. He claims that in 2017 Reich "told me that I should avoid being seen working with an African-American work colleague if I did not want to be viewed in the same way as that 'lazy nigger.'"

Magana details two occasions in 2018 when Reich "suggested hiring 'illegals' because they will accept less compensation," and resisted Magana's recommendations for which employees should get raises, allegedly saying, "'aren't these guys illegal?'"

Further in the complaints he recounts a 2019 meeting in which management for a newly acquired building near Loyola University on the north side was allegedly discussed. "My African American colleague asked, 'who will be managing the building,' to which Mr. Reich responded, 'they've never seen a Regional Manager of your kind in that area.' I asked about getting access to the roof top, to which Mr. Martay stated, 'Yeah I can imagine Armando showing up with his trash can and saying "Hello I'm Armando, the janitor here to clean up after you."'"

Later that year, Magana alleges he "met with Mr. Reich at a property that Pangea had recently begun to manage. During a discussion regarding employee staff assignments, Mr. Reich remarked that 'Mexicans are for custodial and maintenance, Blacks for property management, and Whites for the back office, that's it.'" The following month Magana alleges that Martay said to him, in front of other employees, "I should make you pull your fucking tools back out and make you clean shit out of the fucking tubs, like you used to."

Magana writes that he reported Martay's "derogatory comments" to Reich and both supervisors' comments to Pangea's HR manager Lori Bysong as well as the company's CFO Patrick Borchard and cofounder and former CEO Steve Joung. "Mr. Joung listened to me, then responded by saying that he doubted workplace discrimination was occurring."

Magana claims in the complaint that at the end of 2019 he also had a conversation with Pangea's operations manager Sean McQuade about hiring and pay for new workers, requesting $22/hour for one of them. "Mr. McQuade responded by asking 'Do you know if he's illegal? Do you think he has papers? . . . Do you think this guy is worth $22/hour?'" Again, Magana claims he reported these comments to HR, Pangea's in-house attorney Jennifer Dean, and other supervisors.

"Despite having complained on multiple occasions directly to multiple members of Pangea management, no one at the Company ever responded to, investigated, or otherwise communicated with me regarding my several complaints," Magana writes. "Rather, Mr. Reich continues to make derogatory, discriminatory comments toward me. Specifically, on May 12, 2020, Mr. Reich called me and stated, 'stop treating me like a shine. Last time I checked I was white.'"

In both an internal e-mail obtained by the Reader and in an e-mailed statement from CEO Pete Martay, Pangea has denied Magana's allegations and said he's refused to cooperate in the company's internal efforts to investigate.

"Pangea Properties has zero tolerance for racist or discriminatory behavior," Martay wrote to the Reader. "We take allegations of this nature very seriously. As a result, we hired a neutral investigator to carry out a prompt and thorough investigation and have also engaged legal representation to defend the company against allegations we believe are baseless. The complainant and his witnesses have refused multiple requests to participate in our investigation."

The Reader also presented the company with an opportunity to respond to additional allegations made by ten other current and former employees about Pangea's corporate culture. These included vivid descriptions of demeaning statements by Reich and other supervisors, as well as allegations of segregated and demeaning working conditions. "We categorically deny the claims in the complaint and also the statements made against us by former employees," wrote Martay. Neither Reich nor McQuade, whose conduct Magana also referenced in his complaint, responded to a request for comment.

Hostile work environments are both ubiquitous and difficult to reform. Their toxicity can be hard to pin down and prove on paper, especially when corporate promotions and official praise are interspersed with interpersonal disrespect and disregard. As a reckoning over the prejudices endemic to white-dominated workplaces roils the private and public sectors, employees of color from businesses and institutions as varied as Adidas, LinkedIn, Vogue, the San Francisco health department, and Loyola University have begun speaking out about the racial microaggressions, gaslighting, and harassment that defines office culture for them.

Even as he received glowing performance reviews, Magana could also feel hostility from management. For example, in an August 2013 e-mail obtained by the Reader, Reich wrote a brief note to another regional manager. The subject line read, "Armando was excited about converting to Islam . . . " and inside the body of the e-mail the sentence ended " . . . Until he found out you can't eat pork." Attached was a photo of Magana, grinning, in a little white hat reminiscent of a kufi skull cap.

When asked about the e-mail Magana said he was dismayed at being the target of a crude joke that appeared to be both Islamophobic and about his weight. "I never thought he was gonna take a picture and send it," he said with a grim chuckle as we looked at the image over beers at the nearly deserted patio of the Promontory in Hyde Park. Magana wore a black valve mask and a short sleeve blue polo, apparently unbothered by the biting gusts of wind on that late September afternoon. As he stared at the photo he said the fact that it had been e-mailed was unusual; in his experience Reich rarely left a paper trail of demeaning comments. "It was always phone calls with Derek," Magana said. "He really doesn't like to put anything in e-mail. If you send him an e-mail, he'll call. If you meet him in the field, he'll make those comments."

As documented in his complaints, Magana attempted to have the "discriminatory communications and behavior" he experienced addressed internally, but complaints to HR and leaders of the company didn't help. Finally he started working with attorney Marc Siegel to appeal to external authorities to intervene. The company soon also hired an outside attorney to help handle the situation.

Pangea's lawyers "kept telling [Siegel] that I was exaggerating and they always treated me good and they weren't being racist toward me," Magana told the Reader. "Long story short, I told my attorney I'm not gonna play this game, I'm gonna file this with the state and city and I'm gonna make it public."

By late spring the stress of working at Pangea had intensified due to the coronavirus pandemic. "I broke down because when the COVID started Derek was just calling me every other day, every other day: 'What are you doing?' I'd say 'We're working . . . but we don't have any sanitizing supplies. We don't have masks.'"

Magana said Pangea didn't offer hazard pay. Some field employees took time off because they were scared to go back into the apartment buildings, especially when word got around that tenants were falling ill. Magana says Reich didn't seem to care. "It was like, 'All these guys need to come back to work.' I'm like, 'Derek we're all working, there's some people who took off because they're scared.'"

Magana said that Reich demanded that he choose five of his staff to fire as part of a company effort to reduce the employee headcount to below 500 so that Pangea could qualify for a Paycheck Protection Program loan from the federal government.

He said that in late March Reich called him. "He says, 'You got any shitty people working for you? Give me five.' I'm like, 'I don't have any shitty people working for me.' He's like, 'Well, give me five.'"

The Reader obtained an e-mail Magana sent to Reich the next day, listing four employees who changed positions in the company without being replaced and one who was about to leave Pangea anyway. "There's your four plus one, he's already out the door," Magana recalled thinking. He said that after that he got another phone call from Reich who demanded he name five additional people to fire because Pangea's employee count was at 512.

Magana said he submitted another list of names. "I was destroyed about that," he said. According to records released by the Small Business Administration in July, Pangea was awarded a $5-$10 million loan through the PPP program. They listed an employee count of 494.

By June, Magana needed a break. The stress of the job was getting to him and affecting his family, and he took a leave of absence for a month and a half. "I got kind of depressed, stressed out, I was trying to take care of my health," he said. "I found out my son was depressed, so I had to dedicate myself to him."

Magana said things got worse for him at Pangea after he came back to work in July. There were sudden extra meetings where he was questioned about his work. He felt increasingly micromanaged.

Nevertheless, Magana was still determined to continue working at the company, where he was making $115,000 in salary, got bonuses, and to which he'd devoted a decade of his life. "I'm happy where I'm at, I'm good at what I do, I've done nothing wrong," he said.

Word about Magana's complaint began to get out at Pangea, and e-mails from pseudonymised accounts suddenly appeared in all field employees' inboxes, sharing Magana's complaints and encouraging them to file their own. The company quickly deleted these e-mails from employees' inboxes, however. In a September 30 e-mail to all field employees obtained by the Reader, Martay acknowledged that deletion, adding that the "current employee" who complained about mistreatment "refused to cooperate and will not speak to the independent investigator" Pangea hired to look into the allegations. Though Martay didn't refer to Magana by name in this e-mail, Magana says he felt the CEO's message was meant to undermine him. "We categorically deny the claims made in the complaint and have engaged legal representation to defend the company against them," Martay wrote.

By the beginning of October, Magana felt he could no longer remain at Pangea. "I cannot continue to work under hostile environment with retaliation," he wrote to me in a text message. Though he technically resigned from his job himself, his attorney argues that he was "constructively discharged" by management because of the "discrimination and harassment and retaliation he faced at work."

According to legal precedent established by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 2006 Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway Co. v. White decision, the definition of retaliation for complaints about workplace discrimination is broad. "It could be making your work life more difficult. It could be micromanaging you. It could be icing you out—anything that could make a reasonable person feel dissuaded from bringing a complaint," said Siegel. "It doesn't have to be a termination or written suspension."

0 notes

Photo

Universal Basic Income as replacement for the welfare state. "Every American age 21+ would get a $13k annual grant. The UBI is to be financed by getting rid of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, etc. By 2020, a UBI will be nearly a trillion dollars cheaper than the current system."

A guaranteed income for every American

Replacing the welfare state with an annual grant is the best way to cope with a radically changing U.S. jobs market—and to revitalize America’s civic culture

Charles Murray | June 3, 2016 11:59 am | The Wall Street Journal

When people learn that I want to replace the welfare state with a universal basic income, or UBI, the response I almost always get goes something like this: “But people will just use it to live off the rest of us!” “People will waste their lives!” Or, as they would have put it in a bygone age, a guaranteed income will foster idleness and vice. I see it differently. I think that a UBI is our only hope to deal with a coming labor market unlike any in human history and that it represents our best hope to revitalize American civil society.

A UBI would present the most disadvantaged among us with an open road to the middle class if they put their minds to it.

The great free-market economist Milton Friedman originated the idea of a guaranteed income just after World War II. An experiment using a bastardized version of his “negative income tax” was tried in the 1970s, with disappointing results. But as transfer payments continued to soar while the poverty rate remained stuck at more than 10% of the population, the appeal of a guaranteed income persisted: If you want to end poverty, just give people money. As of 2016, the UBI has become a live policy option. Finland is planning a pilot project for a UBI next year, and Switzerland is voting this weekend on a referendum to install a UBI.

The UBI has brought together odd bedfellows. Its advocates on the left see it as a move toward social justice; its libertarian supporters (like Friedman) see it as the least damaging way for the government to transfer wealth from some citizens to others. Either way, the UBI is an idea whose time has finally come, but it has to be done right.

First, my big caveat: A UBI will do the good things I claim only if it replaces all other transfer payments and the bureaucracies that oversee them. If the guaranteed income is an add-on to the existing system, it will be as destructive as its critics fear.

Second, the system has to be designed with certain key features. In my version, every American citizen age 21 and older would get a $13,000 annual grant deposited electronically into a bank account in monthly installments. Three thousand dollars must be used for health insurance (a complicated provision I won’t try to explain here), leaving every adult with $10,000 in disposable annual income for the rest of their lives.

People can make up to $30,000 in earned income without losing a penny of the grant. After $30,000, a graduated surtax reimburses part of the grant, which would drop to $6,500 (but no lower) when an individual reaches $60,000 of earned income. Why should people making good incomes retain any part of the UBI? Because they will be losing Social Security and Medicare, and they need to be compensated.

The UBI is to be financed by getting rid of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, Supplemental Security Income, housing subsidies, welfare for single women and every other kind of welfare and social-services program, as well as agricultural subsidies and corporate welfare. As of 2014, the annual cost of a UBI would have been about $200 billion cheaper than the current system. By 2020, it would be nearly a trillion dollars cheaper.

Finally, an acknowledgment: Yes, some people will idle away their lives under my UBI plan. But that is already a problem. As of 2015, the Current Population Survey tells us that 18% of unmarried males and 23% of unmarried women ages 25 through 54—people of prime working age—weren’t even in the labor force. Just about all of them were already living off other people’s money. The question isn’t whether a UBI will discourage work, but whether it will make the existing problem significantly worse.

I don’t think it would. Under the current system, taking a job makes you ineligible for many welfare benefits or makes them subject to extremely high marginal tax rates. Under my version of the UBI, taking a job is pure profit with no downside until you reach $30,000—at which point you’re bringing home way too much ($40,000 net) to be deterred from work by the imposition of a surtax.

Some people who would otherwise work will surely drop out of the labor force under the UBI, but others who are now on welfare or disability will enter the labor force. It is prudent to assume that net voluntary dropout from the labor force will increase, but there is no reason to think that it will be large enough to make the UBI unworkable.

Involuntary dropout from the labor force is another matter, which brings me to a key point: We are approaching a labor market in which entire trades and professions will be mere shadows of what they once were. I’m familiar with the retort: People have been worried about technology destroying jobs since the Luddites, and they have always been wrong. But the case for “this time is different” has a lot going for it.

When cars and trucks started to displace horse-drawn vehicles, it didn’t take much imagination to see that jobs for drivers would replace jobs lost for teamsters, and that car mechanics would be in demand even as jobs for stable boys vanished. It takes a better imagination than mine to come up with new blue-collar occupations that will replace more than a fraction of the jobs (now numbering 4 million) that taxi drivers and truck drivers will lose when driverless vehicles take over. Advances in 3-D printing and “contour craft” technology will put at risk the jobs of many of the 14 million people now employed in production and construction.

The list goes on, and it also includes millions of white-collar jobs formerly thought to be safe. For decades, progress in artificial intelligence lagged behind the hype. In the past few years, AI has come of age. Last spring, for example, a computer program defeated a grandmaster in the classic Asian board game of Go a decade sooner than had been expected. It wasn’t done by software written to play Go but by software that taught itself to play—a landmark advance. Future generations of college graduates should take note.

https://youtu.be/TnUYcTuZJpM?t=1m28s

Exactly how bad is the job situation going to be? An Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development study concluded that 9% of American jobs are at risk. Two Oxford scholars estimate that as many as 47% of American jobs are at risk. Even the optimistic scenario portends a serious problem. Whatever the case, it will need to be possible, within a few decades, for a life well lived in the U.S. not to involve a job as traditionally defined. A UBI will be an essential part of the transition to that unprecedented world.

The good news is that a well-designed UBI can do much more than help us to cope with disaster. It also could provide an invaluable benefit: injecting new resources and new energy into an American civic culture that has historically been one of our greatest assets but that has deteriorated alarmingly in recent decades.

A key feature of American exceptionalism has been the propensity of Americans to create voluntary organizations for dealing with local problems. Tocqueville was just one of the early European observers who marveled at this phenomenon in the 19th and early 20th centuries. By the time the New Deal began, American associations for providing mutual assistance and aiding the poor involved broad networks, engaging people from the top to the bottom of society, spontaneously formed by ordinary citizens.

These groups provided sophisticated and effective social services and social insurance of every sort, not just in rural towns or small cities but also in the largest and most impersonal of megalopolises. To get a sense of how extensive these networks were, consider this: When one small Midwestern state, Iowa, mounted a food-conservation program during World War I, it engaged the participation of 2,873 church congregations and 9,630 chapters of 31 different secular fraternal associations.

Did these networks successfully deal with all the human needs of their day? No. But that isn’t the right question. In that era, the U.S. had just a fraction of today’s national wealth. The correct question is: What if the same level of activity went into civil society’s efforts to deal with today’s needs—and financed with today’s wealth?

The advent of the New Deal and then of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society displaced many of the most ambitious voluntary efforts to deal with the needs of the poor. It was a predictable response. Why continue to contribute to a private program to feed the hungry when the government is spending billions of dollars on food stamps and nutrition programs? Why continue the mutual insurance program of your fraternal organization once Social Security is installed? Voluntary organizations continued to thrive, but most of them turned to needs less subject to crowding out by the federal government.

This was a bad trade, in my view. Government agencies are the worst of all mechanisms for dealing with human needs. They are necessarily bound by rules applied uniformly to people who have the same problems on paper but who will respond differently to different forms of help. Whether religious or secular, nongovernmental organization are inherently better able to tailor their services to local conditions and individual cases.

Under my UBI plan, the entire bureaucratic apparatus of government social workers would disappear, but Americans would still possess their historic sympathy and social concern. And the wealth in private hands would be greater than ever before. It is no pipe dream to imagine the restoration, on an unprecedented scale, of a great American tradition of voluntary efforts to meet human needs. It is how Americans, left to themselves, have always responded. Figuratively, and perhaps literally, it is in our DNA.

Regardless of what voluntary agencies do (or fail to do), nobody will starve in the streets. Everybody will know that, even if they can’t find any job at all, they can live a decent existence if they are cooperative enough to pool their grants with one or two other people. The social isolates who don’t cooperate will also be getting their own monthly deposit of $833.

Some people will still behave irresponsibly and be in need before that deposit arrives, but the UBI will radically change the social framework within which they seek help: Everybody will know that everybody else has an income stream. It will be possible to say to the irresponsible what can’t be said now: “We won’t let you starve before you get your next deposit, but it’s time for you to get your act together. Don’t try to tell us you’re helpless, because we know you aren’t.”

The known presence of an income stream would transform a wide range of social and personal interactions. The unemployed guy living with his girlfriend will be told that he has to start paying part of the rent or move out, changing the dynamics of their relationship for the better. The guy who does have a low-income job can think about marriage differently if his new family’s income will be at least $35,000 a year instead of just his own earned $15,000.

Or consider the unemployed young man who fathers a child. Today, society is unable to make him shoulder responsibility. Under a UBI, a judge could order part of his monthly grant to be extracted for child support before he ever sees it. The lesson wouldn’t be lost on his male friends.

Or consider teenage girls from poor neighborhoods who have friends turning 21. They watch—and learn—as some of their older friends use their new monthly income to rent their own apartments, buy nice clothes or pay for tuition, while others have to use the money to pay for diapers and baby food, still living with their mothers because they need help with day care.

“A powerful critique of the current system is that the most disadvantaged people in America have no reason to think that they can be anything else. They are poorly educated, without job skills, and live in neighborhoods where prospects are bleak. “– Charles Murray

These are just a few possible scenarios, but multiply the effects of such interactions by the millions of times they would occur throughout the nation every day. The availability of a guaranteed income wouldn’t relieve individuals of responsibility for the consequences of their actions. It would instead, paradoxically, impose responsibilities that didn’t exist before, which would be a good thing.

Emphasizing the ways in which a UBI would encourage people to make better life choices still doesn’t do justice to its wider likely benefits. A powerful critique of the current system is that the most disadvantaged people in America have no reason to think that they can be anything else. They are poorly educated, without job skills, and live in neighborhoods where prospects are bleak. Their quest for dignity and self-respect often takes the form of trying to beat the system.

The more fortunate members of society may see such people as obstinately refusing to take advantage of the opportunities that exist. But when seen from the perspective of the man who has never held a job or the woman who wants a stable family life, those opportunities look fraudulent.

My version of a UBI would do nothing to stage-manage their lives. In place of little bundles of benefits to be used as a bureaucracy specifies, they would get $10,000 a year to use as they wish. It wouldn’t be charity—every citizen who has turned 21 gets the same thing, deposited monthly into that most respectable of possessions, a bank account.

A UBI would present the most disadvantaged among us with an open road to the middle class if they put their minds to it. It would say to people who have never had reason to believe it before: “Your future is in your hands.” And that would be the truth.

Mr. Murray is the W.H. Brady Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. His book advocating a universal basic income, “In Our Hands: A Plan to Replace the Welfare State,” was first published by AEI in 2006. A revised edition will be out later this month.

This article was found online at: http://ift.tt/1U9bn5O

1 note

·

View note

Text

Division of Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation

It notes that there are division of energy employees occupational illness compensation additionally exceptions within the Social Safety Act for sure federal employees, ministers, and others. Regulatory seize occurs when a state company designed to act in the general public interest instead acts to advance the interests of an essential energy workers compensation program stakeholder group. Requires the President, within a 12 months and no less than each four years thereafter, to enter into a joint agreement with the National Academy of Public Administration and NAS to conduct a policy evaluation of climate change mitigation and adaptation choices. In order for a claim to be accepted under dose reconstruction, NIOSH must discover that there's at least a fifty % chance that the claimant’s most cancers was attributable to occupational radiation exposure. An additional 151 circumstances were denied after dose reconstruction, as a result of NIOSH establishedthat the chance that the claimant’s cancer was associated to their work with radioactive supplies at less than fifty %. It allows eligible claimants to be compensated with out the completion of a NIOSH radiation dose reconstruction or willpower of the chance of causation. Dose reconstruction is used to find out whether to compensate veterans for other diseases. Nationwide, almost two-thirds of the instances involving dose reconstruction have been rejected by the Labor Division.

The availability of claimant information and the need to rework some instances in view of new claimant info or changes to scientific methodologies concerned in determining exposures can also affect processing times. The directive requires each intelligence neighborhood agency to determine policies and procedures that prohibit retaliation and to create a process by way of which the agency's Inspector Normal can assessment personnel or safety clearance choices alleged to be retaliatory. September 2013 and in December 2013. CNG expects to use the remainder of the net proceeds for capital expenditures and common corporate purposes. Resulting from the end of the CTA charge, the CTA regulatory liabilities are categorised as current regulatory liabilities as of December 31, 2013 and the regulatory assets not associated to the CTA are reclassified as long-term regulatory belongings. These rights were subsequently removed via the 2013 NDAA (handed previous to Edward Snowden's disclosures) and not apply. I've been asked to testify due to my prior expertise with implementing similar packages up to now.

All other Local Distribution Adjustment gadgets don't have any affect on Berkshire’s outcomes of operations since they're a move-via. Modifications in those assumptions could have a material impact on pension and different postretirement expenses. Changes to earnings and expense gadgets related to distribution have a direct impact on net revenue and earnings per share. UIL Holdings’ annual revenue tax expense and related effective tax fee is impacted by variations between the timing of deferred tax non permanent difference exercise and deferred tax restoration. No, you don't want an legal professional. The U.S. Advantage Systems Safety Board (MSPB) uses agency legal professionals within the place of "administrative law judges" to decide federal employees' whistleblower appeals. Manager pay may be suspended in situations the place there was a whistleblower reprisal or different crime. If a chimney technician services your home and he falls off your roof and has a significant injury, guess who is required to pay for his medical payments and misplaced work? Principal Accounting Fees and Services.

In spring 2017, we performed an internet survey of 2000 Albertans who had engaged in paid employment in the province in the course of the previous 12 months. Requires covered entities to provide financial assurance to EPA to display that they have the assets to be in compliance when the term offset expires. UI’s credit ranking would have to decline two ratings at Commonplace & Poor’s and three scores at Moody’s to fall below funding grade. Every staff compensation program is an funding. Countermeasures damage compensation program. Virginia Workers’ Compensation Fee employees carry employees' compensation. The Kentucky decision founds unconstitutionality on a distinction between the overwhelming majority of workers and a very small minority, teachers. In the event you have been injured whereas working at the Oak Ridge Division of Vitality facility or other vitality-related organization, contact the EEOICPA attorneys of the Legislation Places of work of Tony Farmer & John Dreiser. Reasons for not refusing unsafe work are related: not wanting to be a troublemaker, feeling nobody would take it critically anyway, stress to maintain working and not knowing about the fitting to refuse. The PC1-IC and PC2-IC programs are for power companies within gasoline distribution, energy transportation, energy development, renewable power, agricultural cooperative, and utilities segments.

A New Compensation Program - Part 2 of 3 Although slowing somewhat during the past year, the renewable power expanded regardless of the global credit crunch specially in the sector of solar, wind and geothermal investment. According to the World Wind Energy Association around 12,000 megawatts of wind power generation capacity were placed in 2008 in addition to 9,740 megawatts of Photovoltaic (PV) solar energy power generation potential. The geothermal sector saw a further 6,000 megawatts of capacity installed and it is considered that 2009 will discover added expansion. One can see the reasoning behind this by going through the signs and symptoms of thyroid storm. People with this disorder will probably experience a heightened heart rate which exceeds 200 beats for each minute, along with palpitations, increased blood pressure, chest pain, and/or shortness of breath. So while I'm an advocate of treating conditions through holistic methods, first thing someone should do with this problem is to navigate to the hospital and receive medical intervention to handle the symptoms. Once the symptoms are under control, it's possible to then start a natural thyroid treatment protocol to assist restore the individual's health back to normal, which I'll discuss shortly. Purple is any shade between red and blue. Violet shades include the purples who have more blue than red. For separating and cleansing energy any shade of violet works extremely well, from the deeper darker shades all the way through lavender. The deeper, darker colors do heavier, deeper cleansing. The lighter lavender hues usually supply a lighter, crisper cleansing.

Strontium-90: Obviously a radioactive isotope of Strontium, Strontium-90 is located in significant amounts in spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste from nuclear reactors. Unfortunately it provides a significantly longer half life than Iodine-131 (28.8 years), and needs better quality treatment to effectively remove from water. Depending on the specific water chemistry, a robust base anion resin (A532E) may be sufficient to get rid of from water, however in more complex situations a nuclear grade anion resin might be necessary. f_auto Most of Japan's tea is grown far on the west in the disaster area. Shizuoka will be the closest major tea producing region which is also alone impacted by radiation. Most with the teas tested from Shizuoka showed trace amounts of radiation, but failed to exceed the security standards set with the government. A few have been discovered to contain radiation in excess in the standards, but only in the dry leaves. Once steeped, rays levels are far below the security limits imposed by the government.

0 notes

Text

House painter and pot farmer from St. Louis resisting Robert Mueller’s Russia probe

Watch Video

ST. LOUIS, Mo. — The way Andrew Miller’s attorneys and associates tell it, he’s just a regular guy with nothing relevant to share with special counsel Robert Mueller.

Miller has worked on and off for Republican political operative Roger Stone for a decade. More recently, he had a gig as a marijuana farmer in California — a business he conducted legally. Now he is working in St. Louis as a house painter. In the summer of 2016, Miller was getting ready for a wedding and was less interested in the presidential election. According to his lawyers, Miller doesn’t know anything about Russian collusion.

Stone was President Donald Trump’s longtime political adviser. He claims his associates are being harassed. One former Stone aide, Sam Nunberg, went on a frantic cable news blitz in the early spring insisting he’d defy his subpoena from Mueller. Another longtime friend of Stone’s, Michael Caputo, compared his interview with special counsel investigators to a “proctology appointment with a very large-handed doctor.”

Stone’s friends and former aides have offered their testimony — except for Miller.

34-year-old Miller, a staunch libertarian, has refused to testify before the grand jury. Instead, he is putting up a constitutional fight challenging Mueller’s authority to oversee the Russia probe. He’s getting an assist from Caputo’s legal defense fund, which is paying for one of Miller’s lawyers, and the conservative National Legal and Policy Center, which is footing the bill for another of Miller’s attorneys. A federal judge has held him in contempt of court for his resistance, positioning him to be jailed if he loses his court cases and still doesn’t comply.

Miller’s legal crusade is set to be the first time that higher federal courts can weigh in on Mueller’s actions as special counsel. If Miller loses his court challenge, then Mueller could have a newer and stronger legal backing behind his work.

“Andrew is just being brave,” said Alicia Dearn, one of Miller’s attorneys. “This is really a matter of principle. This isn’t a matter of him having anything to hide or even wanting to frustrate the special counsel’s office.”

Dearn said that if Miller ultimately loses his court challenge, he will testify rather than go to jail.

In a statement to CNN, Stone described his former aide as a “pugnacious bantam rooster” who is both blunt and genuine in his commitment to personal freedoms.

“He’s a good father, a devoted husband and a loyal friend,” Stone said. “The efforts to squeeze him to bear false witness against me are despicable.”

A spokesman for the special counsel declined to comment.

Miller first got to know Stone through his stepmother, who was Stone’s former personal assistant. In the decade since, he has worked as Stone’s driver, traveling aide and tech guy. He has tended to the fan mail, spam and media requests that flooded the inbox of the StoneZone, the official website for Stone’s clips, quips and columns.

When Kristin Davis — also known as the ‘Manhattan Madam’ for running a high-end prostitution ring — ran for governor of New York in 2010, Stone worked as her campaign strategist and Miller as her campaign manager.

In 2016 — soon after his wedding — Miller accompanied Stone to the Republican National Convention in Cleveland to ferry him around and keep track of his appointments.

The super PAC run by Stone paid $9,000 to A Miller Research — a company run by Miller — during the 2016 election cycle, according to Federal Election Commission reports. Miller’s attorney has said it was compensation for scheduling appointments and media appearances for Stone. Stone has said it was for IT work. Another political group affiliated with Stone paid Miller’s firm $5,000 for “consulting,” according to FEC reports.

Dearn said she isn’t sure what Mueller is looking for when it comes to Stone, but she’s quite certain her client isn’t in possession of it.

“I don’t think that he is the linchpin for whatever it is they’re seeking on Roger Stone,” Dearn said.

Miller’s case is complicated by the fact that he initially cooperated with the special counsel’s investigation. When FBI agents first approached him in May, he spoke with them at his home in St. Louis for two hours without an attorney. At the end of the interview, they handed him grand jury subpoenas for testimony and documents, according to a recent court filing he made.

Afterward, he reached out to Dearn.

The two first met while working for the 2012 Libertarian presidential campaign of former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson, for which she was general counsel and he was a traveling aide.

Dearn put the kibosh on Miller’s plan to meet with investigators a few days later for an informal interview.

After a protracted back and forth between Dearn and Mueller’s team, Miller handed over a tranche of documents. In turn, the government had agreed to limit its search to certain terms such as Stone, WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, Guccifer 2.0, DCLeaks and the Democratic National Committee, according to court filings and interview with attorneys.

Dearn was adamant that Miller not be forced to testify to the grand jury about one topic in specific: Stone. She asked that her client be granted immunity, “otherwise he’s going to have to take the Fifth Amendment,” she said in a court hearing in June.

Aaron Zelinsky, one of Mueller’s prosecutors, noted Miller’s lawyer was making two seemingly contradictory arguments: “On the one hand, that the witness knows nothing, has nothing to hide, and has participated in no illegal activity. On the other hand, that there is a Fifth Amendment concern there.”

In the hearing, Dearn said she was concerned Miller would be asked about his finances and transactions related to political action committees he worked on with Stone.

Dearn said in an interview that she was just being “carefully paranoid” and protecting her client from accidentally committing perjury if he testifies and contradicts something he told investigators back in May without a lawyer present.

Miller “had absolutely no communication with anybody from Russia or with Guccifer or WikiLeaks,” Dearn said in an interview.

By process of elimination, the only thing she believes her client could get caught up on are questions about his financial entanglements with Stone and his super PAC.

Shan Wu, a CNN legal analyst and criminal defense attorney who, for a period, defended former Trump campaign aide Rick Gates in the Russia probe, can see it both ways.

“It’s possible he really does know something and they’re trying to protect him,” by preventing Miller from testifying, Wu said.

Or perhaps Miller really is just a regular guy who knows nothing of interest and that’s what makes him the ideal witness to mount this challenge.

“They’re looking for any vehicle to challenge Mueller,” Wu said of outside groups like the National Legal and Policy Center. “You can pitch this guy as a regular American working stiff who’s being caught up in this.”

That’s exactly how Dearn has cast her client, as a “normal blue-collar kind of guy” who was born and raised in Missouri by a family of liberal union workers.

Miller — a slight man with a hipster-esque style that Stone described as “anti-fashion” — recently decided to give up pot farming and his gig as a volunteer firefighter in California. In May, he moved his family back to his hometown of St. Louis and started painting houses. He wanted his 4-year-old daughter to grow up closer to family and with more readily available playmates than woodsy Lakehead, California, had to offer, friends said.

He hasn’t publicized his plight on television and mainly finds media attention stressful, Dearn said.

“I think that he mostly, despite all of this litigation that’s going on, he mostly wants peace and quiet,” she added.

But challenging Mueller’s authority leaves little room for that.

A DC District Court judge denied Miller’s request to quash his grand jury subpoena. Miller had alleged that Mueller doesn’t have the authority to oversee the Russia probe. But Chief Judge Beryl Howell emphatically wrote that Mueller did and Miller needed to speak to the grand jury. Howell became one of four federal judges who have upheld Mueller’s appointment and constitutional authority amid court challenges.

After Miller skipped out on his scheduled grand jury appearance, he was held in contempt of court earlier this month. His lawyers have filed an appeal and are angling to take their case to the Supreme Court. The appeal isn’t slated to be heard in court until after October 9, raising the question of whether Mueller would move forward in his grand jury investigation sooner without Miller.

In recent days, the indicted Russian company Concord Management and Consulting has tried to jump on board Miller’s appeal, while calling him a “recalcitrant witness” in Mueller’s probe. Miller, in one recent court filing, insists he’s been cooperative.

“This is the best client, I would think, to bring this issue — one who’s not being obstructive but who is being cooperative,” said Paul Kamenar, Miller’s attorney through the National Legal and Policy Center. “Even if we were to lose, we would have done a public service by dispelling any doubts about whether or not special counsels like Mueller are unconstitutional.”

from FOX 4 Kansas City WDAF-TV | News, Weather, Sports https://fox4kc.com/2018/08/26/house-painter-and-pot-farmer-from-st-louis-resisting-robert-muellers-russia-probe/

from Kansas City Happenings https://kansascityhappenings.wordpress.com/2018/08/26/house-painter-and-pot-farmer-from-st-louis-resisting-robert-muellers-russia-probe/

0 notes

Photo

How Income Taxes Work

Provided by your Grain Valley tax preparation office.

The Internal Revenue Service estimates that taxpayers and businesses spend 6.1 billion hours a year complying with tax-filing requirements. To put this into perspective, if all this work were done by a single company, it would need about three million full-time employees and be one of the largest industries in the U.S.¹

As complex as the details of taxes can be, the income tax process is fairly straightforward. However, the majority of Americans would rather not understand the process, which explains why more than half hire a tax professional to assist in their annual filing.²

The tax process starts with income, and generally, most income received is taxable. A taxpayer’s gross income includes income from work, investments, interest, pensions, as well as other sources. The income from all these sources is added together to arrive at the taxpayers’ gross income.

What’s not considered income? Child support payments, gifts, inheritances, workers’ compensation benefits, welfare benefits, or cash rebates from a dealer or manufacturer.³

From gross income, adjustments are subtracted. These adjustments may include alimony, retirement plan contributions, half of self-employment, and moving expenses, among other items.

The result is the adjusted gross income.

From adjusted gross income, deductions are subtracted. With deductions, taxpayers have two choices: the standard deduction or itemized deductions, whichever is greater. The standard deduction amount varies based on filing status, as shown on this chart:

Itemized deductions can include state and local taxes, charitable contributions, the interest on a home mortgage, certain unreimbursed job expenses, and even the cost of having your taxes prepared, among other things.

Once deductions have been subtracted, the personal exemption is subtracted. For the 2017 tax year, the personal exemption amount is $4,050, regardless of filing status.

The result is taxable income. Taxable income leads to gross tax liability.

Fast Fact: No Pencil and Paper. The IRS reports that about 40% of taxpayers use tax preparation software. Source: IRS, 2017

But it’s not over yet.

Any tax credits are then subtracted from the gross tax liability. Taxpayers may receive credits for a variety of items, including energy-saving improvements.

The result is the taxpayer’s net tax.

Understanding how the tax process works is one thing. Doing the work is quite another. Remember, this material is not intended as tax or legal advice. Please consult your Grain Valley or Blue Springs tax professional for specific information regarding your individual situation.

Mike Mead, EA, CTC Alliance Financial & Income Tax 807 NW Vesper Street Blue Springs, MO. 64015 P - 816-220-2001 x201 F - 816-220-2012 AFITOnline.com

Who is Alliance Financial & Income Tax

September 28, 2016

U.S. News and World Report, March 2, 2016

The tax code allows an individual to gift up to $14,000 per person in 2017 without triggering any gift or estate taxes. An individual can give away up to $5,490,000 without owing any federal tax. Couples can leave up to $10,980,000 without owing any federal tax. Also, keep in mind that some states may have their own estate tax regulations.

0 notes

Photo

"Universal Basic Income as replacement for the welfare state. "Every American age 21+ would get a $13k annual grant. The UBI is to be financed by getting rid of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, etc. By 2020, a UBI will be nearly a trillion dollars cheaper than the current system.""- Detail: A guaranteed income for every American Replacing the welfare state with an annual grant is the best way to cope with a radically changing U.S. jobs market—and to revitalize America’s civic culture Charles Murray | June 3, 2016 11:59 am | The Wall Street Journal When people learn that I want to replace the welfare state with a universal basic income, or UBI, the response I almost always get goes something like this: “But people will just use it to live off the rest of us!” “People will waste their lives!” Or, as they would have put it in a bygone age, a guaranteed income will foster idleness and vice. I see it differently. I think that a UBI is our only hope to deal with a coming labor market unlike any in human history and that it represents our best hope to revitalize American civil society. A UBI would present the most disadvantaged among us with an open road to the middle class if they put their minds to it. The great free-market economist Milton Friedman originated the idea of a guaranteed income just after World War II. An experiment using a bastardized version of his “negative income tax” was tried in the 1970s, with disappointing results. But as transfer payments continued to soar while the poverty rate remained stuck at more than 10% of the population, the appeal of a guaranteed income persisted: If you want to end poverty, just give people money. As of 2016, the UBI has become a live policy option. Finland is planning a pilot project for a UBI next year, and Switzerland is voting this weekend on a referendum to install a UBI. The UBI has brought together odd bedfellows. Its advocates on the left see it as a move toward social justice; its libertarian supporters (like Friedman) see it as the least damaging way for the government to transfer wealth from some citizens to others. Either way, the UBI is an idea whose time has finally come, but it has to be done right. First, my big caveat: A UBI will do the good things I claim only if it replaces all other transfer payments and the bureaucracies that oversee them. If the guaranteed income is an add-on to the existing system, it will be as destructive as its critics fear. Second, the system has to be designed with certain key features. In my version, every American citizen age 21 and older would get a $13,000 annual grant deposited electronically into a bank account in monthly installments. Three thousand dollars must be used for health insurance (a complicated provision I won’t try to explain here), leaving every adult with $10,000 in disposable annual income for the rest of their lives. People can make up to $30,000 in earned income without losing a penny of the grant. After $30,000, a graduated surtax reimburses part of the grant, which would drop to $6,500 (but no lower) when an individual reaches $60,000 of earned income. Why should people making good incomes retain any part of the UBI? Because they will be losing Social Security and Medicare, and they need to be compensated. The UBI is to be financed by getting rid of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, Supplemental Security Income, housing subsidies, welfare for single women and every other kind of welfare and social-services program, as well as agricultural subsidies and corporate welfare. As of 2014, the annual cost of a UBI would have been about $200 billion cheaper than the current system. By 2020, it would be nearly a trillion dollars cheaper. Finally, an acknowledgment: Yes, some people will idle away their lives under my UBI plan. But that is already a problem. As of 2015, the Current Population Survey tells us that 18% of unmarried males and 23% of unmarried women ages 25 through 54—people of prime working age—weren’t even in the labor force. Just about all of them were already living off other people’s money. The question isn’t whether a UBI will discourage work, but whether it will make the existing problem significantly worse. I don’t think it would. Under the current system, taking a job makes you ineligible for many welfare benefits or makes them subject to extremely high marginal tax rates. Under my version of the UBI, taking a job is pure profit with no downside until you reach $30,000—at which point you’re bringing home way too much ($40,000 net) to be deterred from work by the imposition of a surtax. Some people who would otherwise work will surely drop out of the labor force under the UBI, but others who are now on welfare or disability will enter the labor force. It is prudent to assume that net voluntary dropout from the labor force will increase, but there is no reason to think that it will be large enough to make the UBI unworkable. Involuntary dropout from the labor force is another matter, which brings me to a key point: We are approaching a labor market in which entire trades and professions will be mere shadows of what they once were. I’m familiar with the retort: People have been worried about technology destroying jobs since the Luddites, and they have always been wrong. But the case for “this time is different” has a lot going for it. When cars and trucks started to displace horse-drawn vehicles, it didn’t take much imagination to see that jobs for drivers would replace jobs lost for teamsters, and that car mechanics would be in demand even as jobs for stable boys vanished. It takes a better imagination than mine to come up with new blue-collar occupations that will replace more than a fraction of the jobs (now numbering 4 million) that taxi drivers and truck drivers will lose when driverless vehicles take over. Advances in 3-D printing and “contour craft” technology will put at risk the jobs of many of the 14 million people now employed in production and construction. The list goes on, and it also includes millions of white-collar jobs formerly thought to be safe. For decades, progress in artificial intelligence lagged behind the hype. In the past few years, AI has come of age. Last spring, for example, a computer program defeated a grandmaster in the classic Asian board game of Go a decade sooner than had been expected. It wasn’t done by software written to play Go but by software that taught itself to play—a landmark advance. Future generations of college graduates should take note. https://youtu.be/TnUYcTuZJpM?t=1m28s Exactly how bad is the job situation going to be? An Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development study concluded that 9% of American jobs are at risk. Two Oxford scholars estimate that as many as 47% of American jobs are at risk. Even the optimistic scenario portends a serious problem. Whatever the case, it will need to be possible, within a few decades, for a life well lived in the U.S. not to involve a job as traditionally defined. A UBI will be an essential part of the transition to that unprecedented world. The good news is that a well-designed UBI can do much more than help us to cope with disaster. It also could provide an invaluable benefit: injecting new resources and new energy into an American civic culture that has historically been one of our greatest assets but that has deteriorated alarmingly in recent decades. A key feature of American exceptionalism has been the propensity of Americans to create voluntary organizations for dealing with local problems. Tocqueville was just one of the early European observers who marveled at this phenomenon in the 19th and early 20th centuries. By the time the New Deal began, American associations for providing mutual assistance and aiding the poor involved broad networks, engaging people from the top to the bottom of society, spontaneously formed by ordinary citizens. These groups provided sophisticated and effective social services and social insurance of every sort, not just in rural towns or small cities but also in the largest and most impersonal of megalopolises. To get a sense of how extensive these networks were, consider this: When one small Midwestern state, Iowa, mounted a food-conservation program during World War I, it engaged the participation of 2,873 church congregations and 9,630 chapters of 31 different secular fraternal associations. Did these networks successfully deal with all the human needs of their day? No. But that isn’t the right question. In that era, the U.S. had just a fraction of today’s national wealth. The correct question is: What if the same level of activity went into civil society’s efforts to deal with today’s needs—and financed with today’s wealth? The advent of the New Deal and then of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society displaced many of the most ambitious voluntary efforts to deal with the needs of the poor. It was a predictable response. Why continue to contribute to a private program to feed the hungry when the government is spending billions of dollars on food stamps and nutrition programs? Why continue the mutual insurance program of your fraternal organization once Social Security is installed? Voluntary organizations continued to thrive, but most of them turned to needs less subject to crowding out by the federal government. This was a bad trade, in my view. Government agencies are the worst of all mechanisms for dealing with human needs. They are necessarily bound by rules applied uniformly to people who have the same problems on paper but who will respond differently to different forms of help. Whether religious or secular, nongovernmental organization are inherently better able to tailor their services to local conditions and individual cases. Under my UBI plan, the entire bureaucratic apparatus of government social workers would disappear, but Americans would still possess their historic sympathy and social concern. And the wealth in private hands would be greater than ever before. It is no pipe dream to imagine the restoration, on an unprecedented scale, of a great American tradition of voluntary efforts to meet human needs. It is how Americans, left to themselves, have always responded. Figuratively, and perhaps literally, it is in our DNA. Regardless of what voluntary agencies do (or fail to do), nobody will starve in the streets. Everybody will know that, even if they can’t find any job at all, they can live a decent existence if they are cooperative enough to pool their grants with one or two other people. The social isolates who don’t cooperate will also be getting their own monthly deposit of $833. Some people will still behave irresponsibly and be in need before that deposit arrives, but the UBI will radically change the social framework within which they seek help: Everybody will know that everybody else has an income stream. It will be possible to say to the irresponsible what can’t be said now: “We won’t let you starve before you get your next deposit, but it’s time for you to get your act together. Don’t try to tell us you’re helpless, because we know you aren’t.” The known presence of an income stream would transform a wide range of social and personal interactions. The unemployed guy living with his girlfriend will be told that he has to start paying part of the rent or move out, changing the dynamics of their relationship for the better. The guy who does have a low-income job can think about marriage differently if his new family’s income will be at least $35,000 a year instead of just his own earned $15,000. Or consider the unemployed young man who fathers a child. Today, society is unable to make him shoulder responsibility. Under a UBI, a judge could order part of his monthly grant to be extracted for child support before he ever sees it. The lesson wouldn’t be lost on his male friends. Or consider teenage girls from poor neighborhoods who have friends turning 21. They watch—and learn—as some of their older friends use their new monthly income to rent their own apartments, buy nice clothes or pay for tuition, while others have to use the money to pay for diapers and baby food, still living with their mothers because they need help with day care. “A powerful critique of the current system is that the most disadvantaged people in America have no reason to think that they can be anything else. They are poorly educated, without job skills, and live in neighborhoods where prospects are bleak. “– Charles Murray These are just a few possible scenarios, but multiply the effects of such interactions by the millions of times they would occur throughout the nation every day. The availability of a guaranteed income wouldn’t relieve individuals of responsibility for the consequences of their actions. It would instead, paradoxically, impose responsibilities that didn’t exist before, which would be a good thing. Emphasizing the ways in which a UBI would encourage people to make better life choices still doesn’t do justice to its wider likely benefits. A powerful critique of the current system is that the most disadvantaged people in America have no reason to think that they can be anything else. They are poorly educated, without job skills, and live in neighborhoods where prospects are bleak. Their quest for dignity and self-respect often takes the form of trying to beat the system. The more fortunate members of society may see such people as obstinately refusing to take advantage of the opportunities that exist. But when seen from the perspective of the man who has never held a job or the woman who wants a stable family life, those opportunities look fraudulent. My version of a UBI would do nothing to stage-manage their lives. In place of little bundles of benefits to be used as a bureaucracy specifies, they would get $10,000 a year to use as they wish. It wouldn’t be charity—every citizen who has turned 21 gets the same thing, deposited monthly into that most respectable of possessions, a bank account. A UBI would present the most disadvantaged among us with an open road to the middle class if they put their minds to it. It would say to people who have never had reason to believe it before: “Your future is in your hands.” And that would be the truth. Mr. Murray is the W.H. Brady Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. His book advocating a universal basic income, “In Our Hands: A Plan to Replace the Welfare State,” was first published by AEI in 2006. A revised edition will be out later this month. This article was found online at: http://ift.tt/2xCvxxj. Title by: RageLionRising Posted By: www.eurekaking.com

0 notes

Text

When it comes to safeguarding federal employees who get sick or injured while working, Federal Worker's Compensation offers significant advantages. For work-related illnesses or injuries, this program, run by the Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP), guarantees that federal employees receive the proper medical attention and compensation. We'll look at the kinds of injuries covered by Federal Workers' Compensation in this blog. If you need any treatment for your work injury or need help with the paperwork of Federal Worker's Compensation Blue Springs, contact Core Medical Center, USA, today.

#Federal Worker's Compensation#Federal Worker's Compensation Blue Springs#Motor Vehicle Accident Injuries Compensation#Blue Springs#USA

0 notes

Text

Troops Who Cleaned Up Radioactive Islands Can’t Get Medical Care

By Dave Philipps, NY Times, Jan. 28, 2017

RICHLAND, Wash.--When Tim Snider arrived on Enewetak Atoll in the middle of the Pacific Ocean to clean up the fallout from dozens of nuclear tests on the ring of coral islands, Army officers immediately ordered him to put on a respirator and a bright yellow suit designed to guard against plutonium poisoning.

A military film crew snapped photos and shot movies of Mr. Snider, a 20-year-old Air Force radiation technician, in the crisp new safety gear. Then he was ordered to give all the gear back. He spent the rest of his four-month stint on the islands wearing only cutoff shorts and a floppy sun hat.

“I never saw one of those suits again,” Mr. Snider, now 58, said in an interview in his kitchen here as he thumbed a yellowing photo he still has from the 1979 shoot. “It was just propaganda.”

Today Mr. Snider has tumors on his ribs, spine and skull--which he thinks resulted from his work on the crew, in the largest nuclear cleanup ever undertaken by the United States military.

Roughly 4,000 troops helped clean up the atoll between 1977 and 1980. Like Mr. Snider, most did not even wear shirts, let alone respirators. Hundreds say they are now plagued by health problems, including brittle bones, cancer and birth defects in their children. Many are already dead. Others are too sick to work.

The military says there is no connection between these illnesses and the cleanup. Radiation exposure during the work fell well below recommended thresholds, it says, and safety precautions were top notch. So the government refuses to pay for the veterans’ medical care.

Congress long ago recognized that troops were harmed by radiation on Enewetak during the original atomic tests, which occurred in the 1950s, and should be cared for and compensated. Still, it has failed to do the same for the men who cleaned up the toxic debris 20 years later. The disconnect continues a longstanding pattern in which the government has shrugged off responsibility for its nuclear mistakes.

On one cleanup after another, veterans have been denied care because shoddy or intentionally false radiation monitoring was later used as proof that there was no radiation exposure.

A report by The New York Times last spring found that veterans were exposed to plutonium during the cleanup of a 1966 accident involving American hydrogen bombs in Palomares, Spain. Declassified documents and a recent study by the Air Force said the men might have been poisoned, and needed new testing.

But in the months since the report, nothing has been done to help them.

For two years, the Enewetak veterans have been trying, without success, to win medical benefits from Congress through a proposed Atomic Veterans Healthcare Parity Act. Some lawmakers hope to introduce a bill this year, but its fate is uncertain. Now, as new cases of cancer emerge nearly every month, many of the men wonder how much longer they can wait.

The cleanup of Enewetak has long been portrayed as a triumph. During the operation, officials told reporters that they were setting a new standard in safety. One report from the end of the cleanup said safety was so strict that “it would be difficult to identify additional radsafe precautions that could have been taken.”

Documents from the time and interviews with dozens of veterans tell a different story.

Most of the documents were declassified and made publicly available in the 1990s, along with millions of pages of other files relating to nuclear testing, and sat unnoticed for years. They show that the government used troops instead of professional nuclear workers to save money. Then it saved even more money by skimping on safety precautions.

Records show that protective equipment was missing or unusable. Troops requesting respirators couldn’t get them. Cut-rate safety monitoring systems failed. Officials assured concerned members of Congress by listing safeguards that didn’t exist.

And though leaders of the cleanup told troops that the islands emitted no more radiation than a dental X-ray, documents show they privately worried about “plutonium problems” and areas that were “highly radiologically contaminated.”

Tying any disease to radiation exposure years earlier is nearly impossible; there has never been a formal study of the health of the Enewetak cleanup crews. The military collected nasal swabs and urine samples during the cleanup to measure how much plutonium troops were absorbing, but in response to a Freedom of Information Act request, it said it could not find the records.

Hundreds of the troops, though, almost all now in their late 50s, have found one another on Facebook and discovered remarkably similar problems involving deteriorating bones and an incidence of cancer that appears to be far above the norm.

A tally of 431 of the veterans by a member of the group shows that of those who stayed on the southernmost island, where radiation was low, only 2 percent reported having cancer. Of those who worked on the most contaminated islands in the north, 20 percent reported cancer. An additional 34 percent from the contaminated islands reported other health problems that could be related to radiation, like failing bones, infertility and thyroid problems.

Between 1948 and 1958, 43 atomic blasts rocked the tiny atoll--part of the Marshall Islands, which sit between Hawaii and the Philippines--obliterating the native groves of breadfruit trees and coconut palms, and leaving an apocalyptic wreckage of twisted test towers, radioactive bunkers and rusting military equipment.

Four islands were entirely vaporized; only deep blue radioactive craters in the ocean remained. The residents had been evacuated. No one thought they would ever return.

In the early 1970s, the Enewetak islanders threatened legal action if they didn’t get their home back. In 1972, the United States government agreed to return the atoll and vowed to clean it up first, a project shared by the Atomic Energy Commission, now called the Department of Energy, and the Department of Defense.

The biggest problem, according to Energy Department reports, was Runit Island, a 75-acre spit of sand blitzed by 11 nuclear tests in 1958. The north end was gouged by a 300-foot-wide crater that documents from the time describe as “a special problem” because of “high subsurface contamination.”

The island was littered with a fine dust of pulverized plutonium, which if inhaled or otherwise absorbed can cause cancer years or even decades later. A millionth of a gram is potentially harmful, and because the isotopes have a half-life of 24,000 years, the danger effectively never goes away.

The military initially quarantined Runit. Government scientists agreed that other islands might be made habitable, but Runit would most likely forever be too toxic, memos show.

So federal officials decided to collect radioactive debris from the other islands and dump it into the Runit crater, then cap it with a thick concrete dome.

The government intended to use private contractors and estimated the cleanup would cost $40 million, documents show. But Congress balked at the price and approved only half the money. It ordered that “all reasonable economies should be realized” by using troops to do the work.

Safety planners intended to use protective suits, respirators and sprinklers to keep down dust. But without adequate funding, simple precautions were scrapped.

Paul Laird was one of the first service members to arrive for the atoll’s cleanup, in 1977. Then a 20-year-old bulldozer driver, he began scraping topsoil that records show contained plutonium. He was given no safety equipment.

“That dust was like baby powder. We were covered in it,” said Mr. Laird, now 60, during an interview in rural Maine, where he owns a small auto repair shop. “But we couldn’t even get a paper dust mask. I begged for one daily. My lieutenant said the masks were on back order so use a T-shirt.”

By the time Mr. Laird left the islands, he was throwing up and had a blisterlike rash. He got out of the Army in 1978 and moved home to Maine. When he turned 52, he found a lump that turned out to be kidney cancer. A scan at the hospital showed he also had bladder cancer. A few years later he developed a different form of bladder cancer.

His private health insurance covered the treatment, but co-payments left him deep in debt. He applied repeatedly for free veterans’ health care for radiation but was denied. His medical records from the military all said he had not been exposed.

“When the job was done, they threw my bulldozer in the ocean because it was so hot,” Mr. Laird said. “If it got that much radiation, how the hell did it miss me?”

As the cleanup continued, federal officials tried to institute safety measures. A shipment of yellow radiation suits arrived on the islands in 1978, but in interviews veterans said that they were too hot to wear in the tropical sun and that the military told them that it was safe to go without them.

The military tried to monitor plutonium inhalation using air samplers. But they soon broke. According to an Energy Department memo, in 1978, only a third of the samplers were working.

All troops were issued a small film badge to measure radiation exposure, but government memos note that humid conditions destroyed the film. Failure rates often reached 100 percent.

Every evening, Air Force technicians scanned workers for plutonium particles before they left Runit. Men said dozens of workers each day had screened positive for dangerous levels of radiation.

“Sometimes we’d get readings that were all the way to the red,” said one technician, David Roach, 57, who now lives in Rockland, Me.

None of the high readings were recorded, said Mr. Roach, who has since had several strokes.

Two members of Congress wrote to the secretary of defense in 1978 with concerns, but his office told them not to worry: Suits and respirators ensured the cleanup was conducted in “a manner as to assure that radiation exposure to individuals is limited to the lowest levels practicable.”

Even after the cleanup, many of the islands were still too radioactive to inhabit.

In 1988, Congress passed a law providing automatic medical care to any troops involved in the original atomic testing. But the act covers veterans only up to 1958, when atomic testing stopped, excluding the Enewetak cleanup crews.

If civilian contractors had done the cleanup and later discovered declassified documents that show the government failed to follow its own safety plan, they could sue for negligence. Veterans don’t have that right. A 1950 Supreme Court ruling bars troops and their families from suing for injuries arising from military service.

The veterans’ only avenue for help is to apply individually to the Department of Veterans Affairs for free medical care and disability payments. But the department bases decisions on old military records--including defective air sampling and radiation badge data--that show no one was harmed. It nearly always denies coverage.

“A lot of guys can’t survive anymore, financially,” said Jeff Dean, 60, who piloted boats loaded with contaminated soil.

Mr. Dean developed cancer at 43, then again two years later. He had to give up his job as a carpenter as the bones in his spine deteriorated. Unpaid medical bills left him $100,000 in debt.

“No one seems to want to admit anything,” Mr. Dean said. “I don’t know how much longer we can wait, we have guys dying all the time.”

0 notes

Text

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) can significantly impair a person's capacity for both cognitive and motor functioning. A customized strategy is needed to navigate the road to recovery, with various therapies being essential in tackling the various obstacles that could come up. If you have any brain injury, then Core Medical Center is here to provide you with Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation along with Psychosocial Support. Our skilled team can help you detect and recover from your injury.

#Psychosocial Support#Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation#Federal Worker's Compensation Blue Springs#Core Medical Center#Blue Springs#USA

0 notes

Text

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) can significantly impair a person's capacity for both cognitive and motor functioning. A customized strategy is needed to navigate the road to recovery, with various therapies being essential in tackling the various obstacles that could come up. If you have any brain injury, then Core Medical Center is here to provide you with Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation along with Psychosocial Support. Our skilled team can help you detect and recover from your injury.

#Psychosocial Support#Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation#Federal Worker's Compensation Blue Springs#Core Medical Center#Blue Springs#USA

0 notes

Text

Core Medical Center stands as a premier medical institution specializing in worker's compensation and work-related injuries in Blue Springs. Our distinguished multidisciplinary team, well-versed in handling worker's compensation cases, delivers outstanding healthcare services. From precise diagnosis to tailoring personalized treatment plans, conducting procedures, therapies, and proficiently managing all documentation and processing for Occupational Injury Claims in Blue Springs, we are dedicated to excellence. Our unwavering support extends to the injured worker and employer throughout the recovery process, ensuring a seamless experience. At Core Medical Center, the synergy of exceptional care and streamlined claims management offers a comprehensive solution for occupational health and well-being in the Blue Springs community. If you opt to get Workers' Compensation Claims Blue Springs or Motor Vehicle Accident Injuries Compensation, contact us. Here you can get the best care and appropriate assistance.

#Workers' Compensation Claims Blue Springs#Motor Vehicle Accident Injuries Compensation#Federal Worker's Compensation Blue Springs#usa

0 notes

Text

Workplace injuries can be disruptive and costly for employees and employers. However, these incidents can be effectively addressed with proper management and support. At Core Medical Center, our specialists provide comprehensive assistance with Federal Worker’s Compensation and Workplace Injury Management Blue Springs. This blog’ll outline seven essential steps to correct workplace injury management.