#HistoryOfChess

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why Chess Still Captivates Us After All These Centuries

There’s something about chess that just sticks. Maybe it’s the silence before a move, or the little adrenaline rush when you spot a tactic your opponent didn’t see coming. Whatever it is, chess continues to pull people in—whether they’re playing online, over a board at a café, or even carving their own handmade pieces.

A Game with Ancient Roots

Chess has been around for well over a thousand years. It started in northern India as a game called chaturanga around the 6th century, and over time made its way west through Persia (where it became shatranj) and into Europe.

By the 15th century, the game had morphed into something close to what we play today. The queen got her powerful moves, pawns were allowed to promote, and the game sped up.

Simple Rules, Endless Possibilities

The rules of chess are easy to learn—but mastering the game is a lifelong journey. There are just six types of pieces, and only one objective: checkmate the opponent's king.

But once the game starts, the possibilities explode. Even after just a few moves, there are billions of ways the game can unfold. It’s no wonder even world champions still get surprised.

The Game of Kings, Legends, and Rivalries

Chess has always had a strong presence in history and culture. In medieval Europe, it was seen as a game for the nobility—a way to train the mind for war. Fast-forward to the 20th century, and it became a stage for global politics.

One of the most famous matches in history was the 1972 World Championship between American Bobby Fischer and Soviet Boris Spassky. It wasn’t just a game—it felt like the Cold War played out on a chessboard.

Modern Chess: Digital, Global, Addictive

Chess is having a serious moment right now. Online platforms like Chess.com and Lichess have made it easy to play with anyone, anywhere, any time. And streamers and content creators have turned it into something fun and watchable, even for beginners.

During the pandemic, millions of people picked up the game, and shows like The Queen’s Gambit helped bring it back into the mainstream. Suddenly, chess was cool again—and more accessible than ever.

Chess Meets AI (And Still Wins Our Hearts)

AI has completely changed the way we understand chess. When IBM’s Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov in 1997, it felt like a turning point. Since then, engines like Stockfish and AlphaZero have taken things to a whole new level.

But instead of making the game less interesting, AI has helped players at every level improve. It’s not about beating the machine—it’s about learning from it and applying those insights to your own play.

Why We Keep Coming Back

At the end of the day, chess isn’t just a game. It’s a mirror. It reflects how you think, how you handle pressure, how patient you are. It’s personal. You win, you lose, you grow. And every game feels just a little different.

You don’t need to be a grandmaster to enjoy chess. Whether you’re battling it out in a tournament, teaching a kid their first game, or making your own custom chess set by hand—there’s something satisfying about the game that keeps calling you back.

One Last Thought

Chess is a rare blend of art, sport, and science. It’s ancient, but constantly evolving. Simple enough for a child to learn, but deep enough to spend a lifetime exploring.

And that’s why it’s never going out of style.

Let me know if you want this formatted for a blog, video script, or even an Instagram caption to match your chess set project vibe!

#HistoryOfChess#DigitalChess#ChessOnline#ChessAddict#ChessLovers#ChessCommunity#ChessCulture#ChessVibes

0 notes

Text

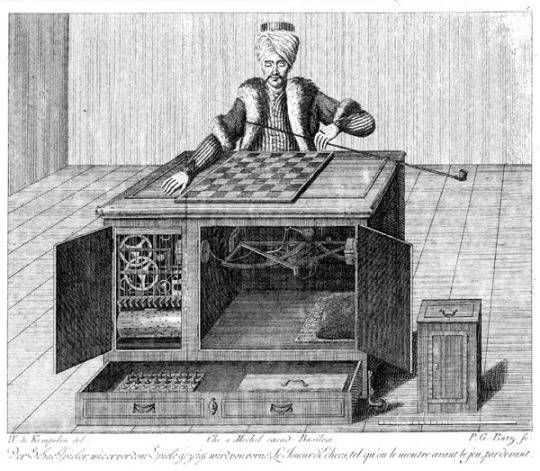

Illusion, Invention, and Apprehension: The Mechanical Chess Master who Stumped (and scared) the World

The game of chess is said to have originated as far back as the 7th century and the earliest known rule book dates back to approximately 840. Over 1000 years later it was still being played, but in all that time no one had ever seen anything like this. This player was a phenomenon. The challengers sat before him and played, engrossed in the game, making all the right moves, and exercising every tactic known to them. He was always silent, still, and played the game with a cool, calm, and collected hand. The reason for this demeanor was obvious, this chess player was not human. This was the Mechanical Turk, a robotic man with a wooden face, dressed in robes and a turban, who sat at a wooden cabinet with a chess board on top. It was bizarre enough to have a chess-playing robot with a running open challenge, but that is not what was so amazing and unnerving to the spectators. What truly stunned them was that no matter who the Mechanical Turk faced, no matter what moves were used and strategy was applied, time and time again the machine beat the man.

The great and mysterious Mechanical Turk was created in 1769 by Wolfgang von Kempelen, an inventor who also happened to be a royal advisor working closely with Empress Maria Theresa of Hungary. After seeing an illusionist perform at Schönbrunn Palace, Kempelen promised the Empress that he could invent something that would far surpass any illusion she had ever seen before. Intrigued by this she allowed him to take a leave of absence to work on the project. He was not gone long. After only six months Kempelen stood before the Empress and the court as his invention was wheeled out, a mechanical man dressed in finery and attached to a four-foot-cabinet with a red and white chess set.

Kempelen explained his creation while opening the various doors and cabinets to the curious eyes of the court. From what they could tell the cabinet was filled with and incredibly complex system of gears, made even more visible by Kempelen illuminating them with a candle. Everyone had an unobstructed view straight through the gears and out the back of the machine, its guts resembling the interior of a massive clock. Then when Kempelen was done with his presentation, it was time for the Mechanical Turk to give his. Kempelen announced he was ready for a challenger.

Charcoal portrait of Kempelen. Image via public domain.

The first man to play against the machine was Austrian courtier Count Ludwig von Cobenzl. The rules were simple, the Mechanical Turk would play using the white pieces and would always make the first move. As the game unfolded it became clear that this was no simple toy. The machine would nod its head a certain number of times depending on the piece being played and it moved its arm and grabbed chess pieces with a disturbingly human manner. It could also communicate through a letter board and did so in multiple languages. It played aggressively, and within a half hour the Count was beaten. He was only the first of many challengers that day to be swiftly and decisively beaten by the Mechanical Turk.

The reaction of the court was a mix of astonishment, suspicion, and confusion. They saw the mechanics, but they also saw it play. How was it possible? As quickly as the players were beaten the theories sprang up with some insisting it was pure trickery and others calling it miraculous. One observer commented on Kempelen, “it seems impossible to attain a more perfect knowledge of mechanics than this gentleman has done.” The mechanical marvel stunned the court, but Kempelen did not share the same enthusiasm about his device. Over time as interest grew in the machine, so did his boredom and disdain with it. People from all over Europe wanted to see it, but Kempelen made up excuse after excuse, saying it needed repairs, saying it was unavailable, anything to avoid bringing it out for a show. He had other projects he wanted to focus on besides this trivial game-playing contraption and in 1774 it was dismantled and retired.

The machine may have been put away, but it was not forgotten. When Joseph II came into sole power in 1780 it was only a year before he called upon Kempelen and ordered him to reassemble the Mechanical Turk to present it to Grand Duke Paul of Russia and his wife while they were visiting Vienna. The Grand Duke loved it, so much so that he told Joseph II that Kempelen should take the machine on a tour around Europe. Kempelen didn’t have much of a choice in the matter, the next two years he was going to be traveling with possibly his most regretted invention.

The grand tour of the Mechanical Turk began in France in 1783 and its reputation brought more skepticism as to how the machine actually worked. A popular theory was that Kempelen hid a child in a secret compartment but that only led to others questioning how a child could be such an intimidating chess player. With the tour through France came some of the machine’s most notable losses, but these were some of the best ranked chess players in the entire world. After playing the machine French composer François-André Danican Philidor, largely considered to be the best chess player of his time, told his son that the game against the mechanical man was “his most fatiguing game of chess ever.” As their time in France came to a close Kempelen’s creation had another high-profile opponent, a chess-playing American by the name of Benjamin Franklin.

After France the next stop on the tour was London where it was on display for the price of five shillings. The audiences were mesmerized by the device. Yes, it was amazing how it played the game, but it went beyond that. The machine seemed to have a human-like ability to interact with whoever it was playing against. Humans are unpredictable, but the machine adapted to every move. Humans can also be dishonest and any time a player attempted to cheat during a game the machine would pick up the piece used in deceit and actually move it back where it belonged before making its own move. Some fully attributed the playing to the supernatural, sometimes sitting as far as possible from the device to avoid the evil spirits powering it. But, as had become usual, for every astonished viewer there was someone who was adamant that it was all just a complicated trick. British author Philip Thicknesse was especially irritated at the notion of the machine’s superpowers. Granted, he gave credit to Kempelen and his brilliance in his invention, but he tried desperately to expose the secrets of the device, firmly believing the theory that it somehow operated under a very real human influence. A 1783 pamphlet shows his frustration with him writing that the thought “That an AUTOMATON can be made to move the Chessmen properly, as a pugnacious player, in consequence of the preceding move of a stranger, who undertakes to play against it, is UTTERLY IMPOSSIBLE…”

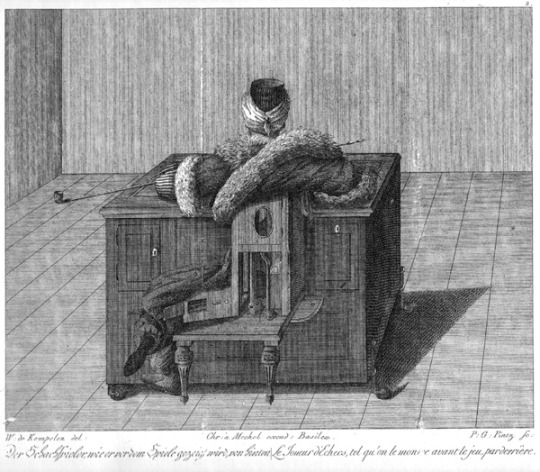

Although a hidden person was probably the most popular theory others believed the movement was somehow controlled by magnets, wires, or some combination of the two. But still, there was the demonstration of the inside of the cabinet before each game. The rumors and speculation followed Kempelen and his machine to their next stops in Germany and Amsterdam. Upon finally returning home Kempelen decided he was done with his famous invention once and for all. The machine was again put into storage inside Schönbrunn Palace. It was still sitting unused when Kempelen died two decades later in 1804 at the age of seventy years old. In perhaps a last attempt to rid himself of it he tried to sell the mechanical man in his final years but could not find a buyer.

Engraving showing the front of the cabinet. Image via public domain.

The mystifying automated man did not see the light of day again until 1805 when Kempelen’s son sold him to Bavarian musician Johann Nepomuk Mälzel for half of his father’s asking price. Mälzel may have had a lot ahead of him, the machine had not run for decades and besides cleaning it up he had to find a way to keep it running. Soon enough though, everything was back in place and the machine was able to continue generating some buzz and collecting victories just as it had since its introduction to the world decades earlier. Mälzel even gave it some updates, installing a mechanical voicebox that would say “check!” upon making its move. Four years after its return to operations the machine faced another high-profile challenger in 1809. But this was no chess master, this was Napoleon Bonaparte.

Many versions of the encounter between the mechanical man and Napoleon were published after the fact and according to one version of events it was a sight to behold. Allegedly the room was arranged so that Napoleon and the machine were seated separately and roped off from each other with Mälzel going between them to make sure all moves were followed. Napoleon disregarded the rules immediately, making the first move against the machine. Mälzel allowed the game to continue but it did not get any better for Napoleon and upon making an illegal move the machine moved his piece back to its original spot. The second time Napoleon tried to make the illegal move the machine removed his piece from the board entirely before continuing to play. When Napoleon attempted a third illegal move the machine decided it had enough. It straightened its arm and with one swift move knocked all the pieces off the board. Like accounts of the match, there are differing reports of Napoleon’s reaction with some saying he was amused and then proceeded to play an honest game, which he then lost, and others saying he returned later for a rematch during which he tried to outsmart the machine by testing it with magnets and trying to obscure its eyes.

For over a decade Mälzel traveled with the machine all over Italy, France, and the United Kingdom (with the exception of a four-year period when the machine was actually sold to someone else and then later purchased back by Mälzel.) Along the way there were some small changes to the act with Mälzel allowing challengers to make the first move and removing the machine’s pawns from the game. After years of successfully parading his device around Europe, it was time to make the jump and bring the marvel to the United States. There was one huge obstacle though, and that was how to make his machine work when he had to leave his secret weapon behind.

Over all these years the most popular theories about the inner workings of the machine said there was a human force behind the mechanical man, others said it had to be a mechanism of magnets or wires. The truth is that all of those guesses were correct.

Since its introduction to the world one of the key parts of the chess challenge was the front of the cabinet being opened and letting the audience see the inside filled with all the gears and pieces that made the machine work on the left side of the cabinet. The right side of the cabinet appeared to be mostly empty, giving the impression there could be nothing hiding inside of it. It was all an illusion. What was invisible to the audience was that the compartment filled with gears did not extend all the way to the back of the cabinet. What lay behind the gears was another compartment where a very human operator could hide and move a sliding seat in order to evade being seen when the presenter opened the doors to the audience. That was the human part of the hoax, then there was the means of seeing the pieces move.

Engraving showing the back of the cabinet. Image via public domain.

The chessboard on the top of the cabinet was very thin and each chess piece had a tiny, strong magnet attached to its base. When they were all put in place on the board above, they corresponded to another magnet underneath that was attached to a string under their places on the board. Each space on the board was also numbered one through sixty-four. These two tactics allowed the person inside the machine to see which pieces moved on the board, where they moved, and which places on the board were affected by a player's movements. The internal magnets were positioned so that outside forces did not influence them which explains how there was no effect when Kempelen would place a large magnet on the side of the board to “prove” that the machine was not run with magnets. The construction of the cabinet was astonishing, but what was even more amazing is that over the years there were multiple chess masters hiding in the machine and playing the games…and none of them ever spilled the secret. With Mälzel looking toward North America he faced the problem of finding a master chess player capable of operating the mechanical man in an entirely different part of the world.

When Mälzel arrived in New York City he was faced with a whole new animal. He had captive audiences, no doubt helped by the newspaper articles advertising his presentations, but he also faced an onslaught of people threatening to tear down the entire act and expose all his secrets. Eventually he reached out to a former operator of the machine, chess master William Schlumberger, and asked if he would travel to the States and resume his role of the unbeatable machine. He obliged and he, Mälzel, and their device began traveling all over the country up and down the east coast, as far west as the Mississippi River, and even touching into Canada. During these latest adventures the machine added at least two more illustrious names to its audience, signer of the Declaration of Independence Charles Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe who went on to write an essay stating that the machine was all an elaborate hoax.

Poster advertising an appearance of the Mechanical Turk. Image via public domain.

It was when the three traveled to Cuba that everything began to unravel for the act that had successfully kept its secrets for decades. While on their second excursion there Schlumberger died of Yellow Fever and then in 1838 Mälzel died at sea while traveling from Cuba back to the United States. The machine eventually fell into the hands of one of Mälzel’s friends who was unsuccessful at auctioning it off. The fate of the chess player was looking bleak until finally an admirer came forward. Poe may have hated the machine when he saw it in Virginia but his personal physician John Kearsley Mitchell now wanted to buy it and restore it to its former glory. After much work the mechanical man was fully restored in 1840, but by now it was over seventy years old. It had traveled the world and stunned millions of people, but the audience for the Mechanical Turk had faded away with the years. The machine was donated to the Chinese Museum of Philadelphia where it eventually disappeared into the collection and was largely forgotten.

On the evening of July 5th 1854 the Chinese Museum caught fire. Dr. Mitchell’s son Silas ran to the scene but by the time he arrived the blaze had already spread too far. The Mechanical Turk, the masterpiece of Wolfgang von Kempelen that traveled the world for decades amazing audiences, the machine that entertained Europe’s royal families and beat Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon Bonaparte, the device that made so many question the limits of invention at a time when industry was shaking the world….was gone. Silas got to the museum only to learn the entire piece was engulfed by flames and destroyed.

Miraculously the secrets of Kempelen’s marvel were somehow kept that way for over seven decades despite the thousands of miles, spectators, and the owners and operators changing hands multiple times. The first official tell-all about the machine was written by Silas Mitchell himself, believing that since the machine was now destroyed there was “no longer any reasons for concealing from the amateurs of chess, the solution to this ancient enigma."

Many accounts and theories of the mysterious chess player were written before its demise, and many were written after. But even after the machine was reduced to dust and Mitchell revealed all there was still a feeling of wonder about it. Multiple copycat machines were made, a play was performed in New York City, and in 1927 a silent film entitled Le Joueur D’Echecs (The Chess Player) debuted in France. Starting in 1984 John Gaughan, a Los Angeles based manufacturer of magician’s equipment began a project to build his own Mechanical Turk. The device was completed five years later and cost over $100,000. Amazingly, there was one piece of the original machine that was not destroyed in the 1854 fire, the chessboard, which was later acquired by Gaughan and used on his machine. The reincarnated chess player was displayed in public for the first time November 1989 at a history of magic conference.

Replica Mechanical Turk. Image via Creative Commons.

When Wolfgang Kempelen returned to the royal court in 1769 he may have thought he was bringing back a simple amusement, but it was far more than an entertaining automated toy. The Mechanical Turk was a marvel and a hoax, an invention and an illusion, and for over seventy years it evoked emotions ranging from delight to rage to absolute terror while forcing people to wonder about the limits of man and machine.

*******************************************************************************

Sources:

How a Phony 18th Century Chess Robot Fooled the World by Evan Andrews history.com/news/how-a-phony-18th-century-chess-robot-fooled-the-world

The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous 19th Century Chess-Playing Machine by Tom Standage (2002)

The Turk, Chess Automaton by Gerald M. Levitt (2000)

#husheduphistory#featuredarticles#chess#chesshistory#historicchessgame#historyofchess#games#gamehistory#boardgamehistory#boardgame#TheMechanicalTurk#inventions#forgottenhistory#weridhistory#strangehistory#oddhistory#historyclass#truthistrangerthanfiction#magic#magichistory#historyofmagic#illusions#famoushoax#hoaxes#history#weirdstort#strangestory#theunknown

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

These mid sized chess pieces from the Philippines are a joy to handle. Hand carved, circa 1950-1970, from Kamagong (darker) and Narra wood, red felted bases and come in their original box. One Kamagong pawn has been replaced. I think they really work well with this board, once set up it’s warming and inviting. The board measures 40 x 40cm. Made from solid oak and walnut. Kamagong is a fruit tree indigenous to the Philippines belonging to the ebony tree family. Like ebony has beautiful subtleties in grain and colour. Traditionally used to make martial arts weapons its is extremely dense and hard, sometimes referred to as “iron wood”, as it is nearly unbreakable. Narra wood is also a local timber, rich mellow yellow colouring, it is also known as red sandalwood. These pieces are slightly bigger to compensate for the higher density and weight of the Kamagong pieces. Since 1984 Narra and Kamagong are considered endangered tree species and protected by Philippine law, making these sets rare. . . . #chess #chessboard #philippines🇵🇭 #oakesandoakes #handmade #slowmade #rarecollection #tabletopgames #queensgambit #chessgambit #historyofchess #chessmusuem #uniquechess #chessnotcheckers #ancientgames #handmadegames #localartisan #artisanmade https://www.instagram.com/p/CoM3bg3oUJ5/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#chess#chessboard#philippines🇵🇭#oakesandoakes#handmade#slowmade#rarecollection#tabletopgames#queensgambit#chessgambit#historyofchess#chessmusuem#uniquechess#chessnotcheckers#ancientgames#handmadegames#localartisan#artisanmade

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The earliest reference of the game occurs in Subandhu's "Vasavadatta" (a classical Sanskrit romantic tale) at the beginning of the seventh century, which tells the popular story of Vasavadatta, the Princess of Ujjayini, and Udayana, King of Vatsa. In this story, the author describes the rainy season as: "The time of the rains played its game with frogs for chessmen (nayadyutair), which, yellow and green in colour, as if mottled with lac, leapt up on the black field (or garden-bed) squares (koshthika)." (a) Macdonell and Thomas have translated it from Sanskrit. The term "nayadyutair" which is translated as chessmen and the comparison of the frogs hopping from plot to plot to the lac-stained chessmen moving from square to square is not inappropriate. (b) It would not be unfair to infer that the two colours are mentioned to indicate the two-handed form of chess (chaturanga). (c) Most interestingly the use of the word "kosht-hiku", a cognate of "kost-higara", for square. The literal meaning of this word is granary or a store-house, which is here used in the technical sense of square of the board. Happy International Chess Day. Source: A History of Chess by Murray, H. J. R. (P.D. 1986) #apastophilic #whatstoday6 #allaboutscience #chess #chessboard #history #historyofchess #chessinindia https://www.instagram.com/p/CC2ZuXfBDAO/?igshid=ouru004zs2ae

0 notes