#How does a SPAC acquisition work?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

This Nomilux Article gives detailed information on Special Purpose Acquisition Company(SPAC) in Luxembourg. For Details, Mail us at: [email protected]

#Establishing a SPAC in Luxembourg#Establishing a Special Purpose Acquisition Company(SPAC) in Luxembourg#Special Purpose Acquisition Company in luxembourg#Special Purpose Acquisition Company(SPAC) in Luxembourg#How much does it cost to start a SPAC?#How does a SPAC acquisition work?#Which structure is the most popular for SPACs?

0 notes

Text

Special-Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC): What Is, Definition, Example, Pros and Cons

A special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a type of corporation which became popular in the United States during the late 1990s and early 2000s. It is a public company that raises money by selling shares to investors and then uses that money to make acquisitions of other companies. The goal of a SPAC is to become a large, publicly-traded company.

SPAC definition

A special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a company/business that exists solely to raise money through an initial public offering (IPO) or the goal of acquiring or merging with another business.

Investors in SPACs come from a wide range of sources, including well-known private equity firms and celebrities to the general public. SPACs must complete their acquisition within two years or return investors' cash.

How does SPAC work

SPACs are mostly investor sponsored. The sponsor is typically a private equity firm, venture capital firm, or investment bank that helps to get the company off the ground by investing its own money into the business and taking it public.

The creators of a SPAC sometimes have at least one acquisition goal in mind, but they don't disclose that target during the IPO process to avoid lengthy disclosures.

Once the SPAC completes its IPO, it has 24 months to consummate a merger or acquisition. If the company fails to do so, it will be liquidated and investors will get their money back.

Benefits of SPACs

SPACs have become increasingly popular in recent years as a way for companies to go public without going through the traditional IPO process.

There are several benefits of going public via a SPAC, including a shorter timeline, fewer regulatory hurdles, and greater flexibility in terms of deal structure.

SPACs also tend to be less expensive than traditional IPOs, making them an attractive option for companies with limited resources.

Perhaps most importantly, SPACs provide a way for companies to access the public markets without giving up control of their business.

For all these reasons, SPACs are likely to continue to grow in popularity in the years to come.

Downsides of SPACs

Although there are many advantages to going public via a SPAC, there are also some potential downsides to consider.

One of the biggest risks is that the SPAC may not be able to find a suitable acquisition target within the allotted time frame. If this happens, the SPAC will be liquidated and investors will lose their money.

Another risk is that the acquired company may not be well-managed, which could lead to financial problems down the road.

Finally, there is the possibility that the SPAC may overpay for the acquired company, which could leave shareholders with significant losses.

While there are some potential risks associated with SPACs, they can still be a viable option for companies looking to go public.

Conclusion

SPAC or Special-purpose acquisition company could be a very beneficial way for a company to go public. There are both positives and negatives to using a SPAC but ultimately it could be a great way to avoid the lengthy IPO process. Considering a SPAC might be a great option for your company.

Originally Published Here: Special-Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC): What Is, Definition, Example, Pros and Cons

from Harbourfront Technologies - Feed https://harbourfronts.com/special-purpose-acquisition-company-spac/

0 notes

Photo

What Is SPAC (Special Purpose Acquisition Company)? Don Butler of Thomvest Ventures gives the following SPAC definition: "You can think of it like this: an IPO is basically a company looking for money, while a SPAC is money looking for a company". So, what is SPAC, and how is it connected with an IPO? Let's dive into details and see the advantages and disadvantages of SPAC companies, whether a SPAC investment is a good choice, and which SPAC stocks are performing the best right now. What Is a SPAC and How Does a SPAC Work? A SPAC (special purpose acquisition company) is a company aiming not to... Read full author’s opinion and review in blog of #LiteFinance http://amp.gs/jpYPz

0 notes

Text

In Focus: GM's EV Ambitions

This week I’m picking up where I left off last week, but I'm not digging into a rumor this week, but instead I'm writing about an ideal circulating Wall Street. Again, I’m sticking with the auto industry, and electric vehicles specifically.

In October GM CEO Mary Barra confidently stated that GM could take the lead from Tesla on electric vehicles. At first the statement threw me for a loop, I actually laughed out loud when I heard it. However, after some thought, I started to believe that Mary Barra is right, and that GM could take the lead from Tesla.

In 2020 Tesla sold just under 500,000 electric vehicles, GM sold 6.8 million vehicles during the same year. Slowly, but surely, the majority of vehicles sold by GM are going to be EVs. GM's sales will be assisted by the economics of car buying, which is, I the car buyer would like to buy a Porsche, but I the car buyer can only afford a Chevy. As GM builds out its selection of EVs, it will be finances or lack thereof, and not a superior product that will help GM take the lead in electric vehicles, but what does that mean for the stock price?

GM overtaking Tesla in EV sales won’t translate into a Tesla like valuation for GM. Elon Musk, Tesla’s CEO, has been very adamant that Tesla is a tech company, not a car company. Elon’s sale’s pitch worked well on investors, and in turn investors have bid Tesla’s stock price up and pushed its valuation to over $1 trillion alongside other tech giants like Apple($AAPL) $2.6 trillion, Amazon ($AMZN) $1.8 trillion, Alphabet/Google ($GOOGL) $1.9 trillion, and Microsoft($MSFT) $2.5 trillion. GM could and probably will sell more EVs than Tesla in the near future, but investors will never value GM like Tesla, because we know that GM is not a tech company.

A GM Rebrand

For investors to think of GM like they think of Tesla, GM would need a major rebrand. The company wouldn’t have to change its name, it would only have to change its image. It would need to do techie things in its EVs and gas powered vehicles. GM would need to make owning a GM vehicle an experience and not just a purchase. This is something that Tesla has excelled at.

We've seen brand new Tesla's with the hood misaligned, with malfunctioning door handles, steering issues, and doors that don't open all the way, and yet, the owners still rave about the experience of owning a Tesla. Tesla's constant software updates that add new functionality to their cars was a feature that was unheard of in the automotive industry. To get investors to view GM like they view Tesla, GM has to figure out how to create a Tesla-like owner experience.

To create that Tesla-like owner's experience GM could go on a spending spree and acquire the companies needed to help transform their cars into real Tesla competitors, but I’m not sure if an automobile manufacturer would know what a good tech acquisition is.

GM could also partner with a tech company, which is something I wrote about last week. This seems like the most reasonable scenario, as it would allow GM to be a car company and another company like Apple, Google, Amazon, or another to give the car all the tech bells and whistles of a Tesla.

GM Hasn't Convinced The Markets

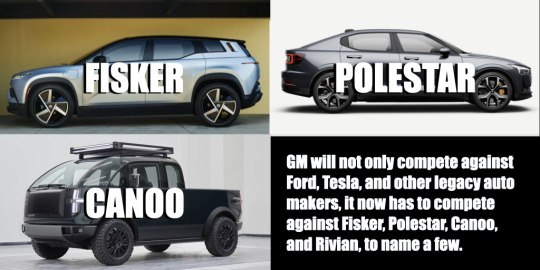

Tesla has made the auto industry a lot more competitive than it was 20 years ago. Investors recently awarded newcomer Rivian ($RIVN) a $100 billion plus valuation, which trumps GM's $86 billion market value. To add insult to injury, Rivian has delivered less than 500 vehicles.

Rivian went public on November 10, 2021 at $78 per share, and within a few days the stock price hit $179 per share before cooling down. Rivian's IPO made investors take a second and third look at other publicly traded EV companies. I'm writing this on November 28, 2021, and during November 2021 Lucid ($LCID) gained close to 30%. Fisker ($FSR) saw a 19% increase. Canoo ($GOEV) increased 50%, Gores Guggenheim ($GGPI), the SPAC that has a planned reverse merger with EV maker Polestar saw a nearly 25% increase, and GM only saw a 9% gain during November. What November's EV stock prices revealed to me is that investors are diversifying their EV bets for second place behind Tesla, and they don't have a strong conviction about GM.

The ideal that GM will take the lead in EVs is conceivable. GM has the infrastructure and resources to build EVs across multiple price ranges, which it will need to do to take the EV lead from Tesla, but I don't think that will translate into a major run up for GM's stock. In order to really compete with Tesla, in order to see a major rise in value, GM has to find a way to better the ownership experience of GM vehicles. If GM can rebrand and make owning a GM vehicle an experience, then I'll consider ranking it up there with Tesla, until then it's just GM, a traditional car maker, doing traditional car maker things.

#GeneralMotors#GM#Electric Hummer#Hummer#GMC#Tesla#Auto#EV#investment education#Financial Education#money#stocks#investing#Apple#Tech#StocksToWatch#StocksToBuy#Canoo#Rivian#Fisker#Polestar

1 note

·

View note

Text

What's a SPAC and how does it help startups in raising money? Decoded

What’s a SPAC and how does it help startups in raising money? Decoded

SPAC is the new buzzword in the deal-making space. It stands for a special-purpose acquisition company and it is a new way for a company to list in public markets. It is becoming very popular with founders in India and abroad. So, what is a SPAC and how does it work? Let’s dive in. A SPAC is essentially a shell company set up with the sole purpose of raising money through an IPO to eventually…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Company That Routes Billions of Text Messages Quietly Says It Was Hacked

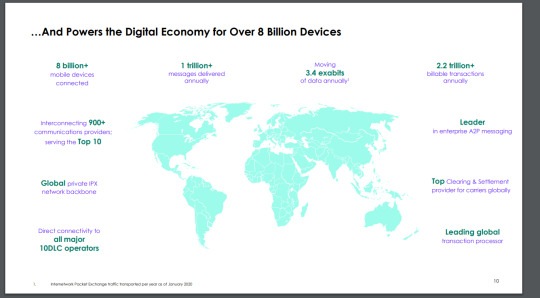

A company that is a critical part of the global telecommunications infrastructure used by AT&T, T-Mobile, Verizon and several others around the world such as Vodafone and China Mobile, quietly disclosed that hackers were inside its systems for years, impacting more than 200 of its clients and potentially millions of cellphone users worldwide.

The company, Syniverse, revealed in a filing dated September 27 with the U.S. Security and Exchange Commission that an unknown "individual or organization gained unauthorized access to databases within its network on several occasions, and that login information allowing access to or from its Electronic Data Transfer (EDT) environment was compromised for approximately 235 of its customers."

A former Syniverse employee who worked on the EDT systems told Motherboard that those systems have information on all types of call records.

Syniverse repeatedly declined to answer specific questions from Motherboard about the scale of the breach and what specific data was affected, but according to a person who works at a telephone carrier, whoever hacked Syniverse could have had access to metadata such as length and cost, caller and receiver's numbers, the location of the parties in the call, as well as the content of SMS text messages.

"Syniverse is a common exchange hub for carriers around the world passing billing info back and forth to each other," the source, who asked to remain anonymous as they were not authorized to talk to the press, told Motherboard. "So it inevitably carries sensitive info like call records, data usage records, text messages, etc. […] The thing is—I don’t know exactly what was being exchanged in that environment. One would have to imagine though it easily could be customer records and [personal identifying information] given that Syniverse exchanges call records and other billing details between carriers."

The company wrote that it discovered the breach in May 2021, but that the hack began in May of 2016.

Do you work or used to work at Syniverse or another telecom provider? Do you have more information about this breach? We’d love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at [email protected], or email [email protected].

Syniverse provides backbone services to wireless carriers like AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and several others around the world. The company processes more than 740 billion text messages every year and has “direct connections” to more than 300 mobile operators around the world, according to its official website. Ninety-five of the top 100 mobile carriers in the world, including the big three U.S. ones, and major international ones such as Telefonica, and America Movil, are Syniverse customers, according to the filing.

To give perspective as to Syniverse’s importance, due to a maintenance update in 2019, Syniverse lost tens of thousands of text messages on Valentine's Day, which meant that the text messages were lost in transit and only delivered months later. Syniverse routes text messages between different carriers both in the U.S. and abroad, allowing people who are on Verizon’s network to communicate with customers who use another carrier. It also manages routing and international roaming between networks, using the notoriously insecure SS7 and Diameter protocols, according to the company's site.

"The world’s largest companies and nearly all mobile carriers rely on Syniverse’s global network to seamlessly bridge mobile ecosystems and securely transmit data, enabling billions of transactions, conversations and connections [daily]," Syniverse wrote in a recent press release.

"Syniverse has access to the communication of hundreds of millions, if not billions, of people around the world. A five-year breach of one of Syniverse's main systems is a global privacy disaster," Karsten Nohl, a security researcher who has studied global cellphone networks for a decade, told Motherboard in an email. "Syniverse systems have direct access to phone call records and text messaging, and indirect access to a large range of Internet accounts protected with SMS 2-factor authentication. Hacking Syniverse will ease access to Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, Amazon and all kinds of other accounts, all at once."

That means the recently discovered and years-long data breach could potentially affect millions—if not billions—of cellphone users, depending on what carriers were affected, according to an industry insider who asked to remain anonymous as he was not authorized to speak to the press.

"With all that information, I could build a profile on you. I'll know exactly what you're doing, who you're calling, what's going on. I'll know when you get a voicemail notification. I'll know who left the voicemail. I'll know how long that voicemail was left for. When you make a phone call, I'll know exactly where you made that phone call from," a telecom industry insider, who asked to remain anonymous as he was not authorized to speak to the press, told Motherboard in a call. "I’ll know more about you than your doctor."

A slide from a Syniverse presentation deck. (Image: Syniverse)

But the former Syniverse employee said that the damage could be much more limited.

"I feel it is extremely embarrassing but likely not the cause of significant damage. It strikes me as a result of some laziness, as I have seen security breaches happen like this a few times," the former employee said. "Because we have not seen anything come out of this over five years. Not saying nothing bad happened but it sounds like nothing did happen."

"Seems like a state-sponsored wet dream," Adrian Sanabria, a cybersecurity expert, told Motherboard in an online chat. "Can't imagine [Syniverse] being a target for anyone else at that scale."

The hack is already raising the alarm in Washington.

“The information flowing through Syniverse’s systems is espionage gold," Sen. Ron Wyden told Motherboard in an emailed statement. "That this breach went undiscovered for five years raises serious questions about Syniverse’s cybersecurity practices. The FCC needs to get to the bottom of what happened, determine whether Syniverse's cybersecurity practices were negligent, identify whether Syniverse's competitors have experienced similar breaches, and then set mandatory cybersecurity standards for this industry.��

“The information flowing through Syniverse’s systems is espionage gold”

In particular, Motherboard asked Syniverse whether the hackers accessed or stole personal data or cellphone users. Syniverse declined to answer that question.

Instead, the company sent a statement that echoed what it wrote in the flining.

"As soon as we learned of the unauthorized activity, we implemented our security incident response plan and engaged a top-tier forensics firm to assist with our internal investigation. We also notified and are cooperating with law enforcement. Syniverse has completed a thorough investigation of the incident which revealed that the individual or organization gained unauthorized access to databases within its network on several occasions and that login information allowing access to or from its EDT environment was compromised for certain customers," the statement read. "All EDT customers have had their credentials reset or inactivated, even if their credentials were not impacted by the incident. We have communicated directly with our customers regarding this matter and have concluded that no additional action is required. In addition to resetting customer credentials, we have implemented substantial additional measures to provide increased protection to our systems and customers."

Syniverse disclosed the breach in an August SEC filing as the company gearing to go public at a valuation of $2.85 billion via a merger with M3-Brigade Acquisition II Corp., a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC). In the document, the company wrote that it "did not observe any evidence of intent to disrupt its operations or those of its customers and there was no attempt to monetize the unauthorized activity. Syniverse did not experience and does not anticipate that these events will have any material impact on its day-to-day operations or services or its ability to access or process data. Syniverse has maintained, and currently maintains, cyber insurance that it anticipates will cover a substantial portion of its expenditures in investigating and responding to this incident."

It's not a household name among customers, but Syniverse is one of the largest companies in the world when it comes to the cellphone infrastructure that helps more well-known companies like Verizon or AT&T to run on a day-to-day basis.

"It is actually surprising that more stuff like this has not happened, considering what a mess Syniverse has become in recent years," the former Syniverse employee told Motherboard in 2019, referring to the Valentine's Day text messaging incident.

The FBI and the FCC did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA) declined to comment.

AT&T, T-Mobile, Vodafone, Telefonica, China Mobile, and America Movil did not respond to a request for comment. Verizon declined to comment.

Subscribe to our new cybersecurity podcast, CYBER. Subscribe to our new Twitch channel.

Company That Routes Billions of Text Messages Quietly Says It Was Hacked syndicated from https://triviaqaweb.wordpress.com/feed/

0 notes

Text

Looking into the Future of a Legal Metaverse?

The Transform Technology Summits start October 13th with Low-Code/No Code: Enabling Enterprise Agility. Register now!

Initially coined in 1992 by Neal Stephenson, the term “ metaverse” comes from his sci-fi novel, Snow Crash, in which humans interact with each other via avatars rendered in three-dimensional virtual space.

As Matthew Ball, the former head of content at Amazon, stated, “The metaverse is a persistent, synchronous and live universe that spans both the digital and physical worlds with total inclusion.” It is described as a digital shared space where everyone can interact seamlessly in a fully immersive, simulated experience. It is the increased permeability of the borders between different digital environments and the physical world. In the metaverse, you can interact with virtual objects in real life with real-time information. A mixture of what is virtual and what is real. A place where people join together to create, work, and spend time together.

It should come as no surprise that tech giants are already all in and building in the metaverse. Games’ Fortnite, Microsoft’s Minecraft, Facebook’s Horizon, and many more are contributors. In fact, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg laid out his vision to transform Facebook from a social media network into a “ metaverse company” in five years. “This is going to be the successor to the mobile internet,” Zuckerberg told shareholders this month. “You’re going to be able to access the metaverse from all different devices and different levels of fidelity from apps on phones and PCs to immersive virtual and augmented reality devices.”

How to engage, work and play in the metaverse

The different types of activities that will take place in the metaverse are limitless. For example, think about COVID-19, where events such as happy hours, weddings, school classes, and work were increasingly taking place with users participating digitally regardless of their actual geographic location. The metaverse presents the opportunity to leverage remote work even further. Virtual conferences and a plethora of tools specifically designed to facilitate collaboration by distributed teams have already come into play.

The metaverse will further offer fully immersive gaming experiences exceeding current Virtual Reality product offerings tenfold. The gaming space seems especially likely to play a role in bringing the metaverse to fruition since video gamers already own some of the most robust computational processors available.

Investing in the metaverse

Companies are continuously trying to up the ante and keep us engaged and entertained.

The “metaverse” is the newest chapter in entertainment, and its growing popularity means investors should at least be familiar with it.

Every day the sector is growing. It’s still unclear what the metaverse will look like, but according to research firm Strategy Analytics, the global metaverse could be worth $280 billion by 2025 and likely grow from there. This market forecast amplifies the interest in metaverse companies bringing new ways to interact with users, which intersects with a world spent indoors and a rise in technological capabilities available to innovators.

With all the buzz surrounding the metaverse, and the rapidly increasing interest from foremost industry leaders, investing in metaverse will undoubtedly be on the rise. Becoming a pioneer in the new has paid off for many; think about all of the Bitcoin millionaires out there. As it stands, the metaverse is shaping up to be the next big wave for investors. Investors, keep an eye on this space.

How does the metaverse change the legal system?

The metaverse is upending our legal and regulatory systems and begs the question of who makes and enforces the rules.

Life is not a game, however. And when you apply old rules to new technology, you will find yourself trying to put a square peg into a round hole. But here goes it:

Intellectual property:when one or more players in a virtual game collaborate to create a virtual good or a virtual world, who owns it? Is it copyrightable? Is it possible to create, protect or enforce a brand inside a virtual world? What strategies can content creators deploy to protect their brands within the virtual world? This is particularly important for consumer-facing businesses.

NFTs: we have all witnessed the cottage industry of value created through tokenization of entertainment, sports, and media personalities and teams through tokenization of non-fungible content. While today the media is focused on entertainment and media content being tokenized in the metaverse, imagine when entire towns, cities, regions, countries, and superstates are created virtually, with the resulting explosion of content. In other words, we have only begun to see the metaverse commercialized through NFTs. Are they securities? Are they currencies? Who regulates? Who can purchase? Who can trade?

Data protection and privacy: as humans spend more and more of their waking (and sometimes sleeping) hours in the metaverse, who owns the resulting data? Who is protecting your identity? What happens if your information or identity is misappropriated? Who is responsible?

These are just examples of the many conundra emanating from the question of who makes the rules and enforces them. Some say that there should be an attempt within every legal system to adapt to the metaverse. Others back the creation of a new legal system specially designed for the metaverse. While the metaverse holds great promise for merchants and investors alike, without a system for design, promulgation, and enforcement of rules, it could be dangerous. For now, the metaverse has been growing in a virtual sandbox. How long will this last? Until the first Meta-tragedy that captures public attention? Or will someone or something lead the charge? The crypto world provides a valuable indicator of what happens when rulemaking remains fully decentralized.

Is a metaverse world far off?

A true metaversemay still be a few years away. In the meantime, Facebook and other pioneers are busy laying the groundwork for a future that permits families, friends, coworkers, and more to meet and interact in shared digital spaces that look and feel authentic. Digital currencies will also be essential.

The metaverse world is in play, and that which is existing separately is gradually coming together. Technology is not proficient enough to support this integrated metaverse just yet, and the reality of its adoption might be a while away. However, the metaverse has the backing of billionaires, talented game designers, and the only rival to the metaverse is life itself.

Louis Lehot is an emerging growth company, venture capital, and M&A lawyer at Foley & Lardner in Silicon Valley. Louis spends his time providing entrepreneurs, innovative companies, and investors with practical and commercial legal strategies and solutions at all stages of growth, from the garage to global.

VentureBeat

VentureBeat’s mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative technology and transact. Our site delivers essential information on data technologies and strategies to guide you as you lead your organizations. We invite you to become a member of our community, to access:

up-to-date information on the subjects of interest to you

our newsletters

gated thought-leader content and discounted access to our prized events, such as Transform 2021: Learn More

networking features, and more

Become a member

About the Author:

Louis Lehot is an emerging growth company, venture capital and M&A lawyer at Foley & Lardner in Silicon Valley. Louis Lehot spends his time providing entrepreneurs, innovative companies, and investors with practical and commercial legal strategies and solutions at all stages of growth, from garage to global. Louis Lehot focuses his efforts on technology, digital health, life science and clean energy innovation. Louis’s clients are public and private companies, financial sponsors, venture capitalists, investors and investment banks, and he has helped hundreds of companies at formation, obtaining financing, solving governing challenges, going public and buying and selling. Louis Lehot is praised by clients, colleagues and industry guides for his business acumen, legal expertise and leadership in Silicon Valley.

Connect with Louis Lehot:

Website: Louis Lehot

Website: Louis Lehot

Chambers: Louis Lehot

LinkedIn: Louis Lehot

Facebook: Louis Lehot

Twitter: Louis Lehot

Instagram: Louis Lehot

YouTube: Louis Lehot

Vimeo: Louis Lehot

Pinterest: Louis Lehot

Ello: Louis Lehot

Magazine Xpert: Louis Lehot

Crunchbase: Louis Lehot

Muckrack: Louis Lehot

Anchor.fm: Louis Lehot

Ideamensch: Louis Lehot

Chief Executive: Louis Lehot

Data Driven Investor: Louis Lehot

Good Men Project: Louis Lehot

Speaker Hub: Louis Lehot

Read the Articles written by Louis Lehot:

Louis Lehot- What to expect for seed and pre-seed stage financing in 2021

Louis Lehot- A Brief Legal Guide To Buying And Selling Shares Of Private Company Stock

Louis Lehot- The IPO Markets Are Changing, And So Is The Lock-up Agreement

Louis Lehot- What are SPACs, and how they are different from IPOs?

Louis Lehot- L2 Counsel Represents AgTech Leader FluroSat In Dagan Acquisition

Louis Lehot- Considering Selling Your Company? Be Clear on Your Fiduciary Duties

Louis Lehot- Incentivizing With Stock Options: What Your Startup Needs To Know About ISOs, NSOs And Other Parts Of The Alphabet Soup

Louis Lehot- Ready To Sell Your Startup In 2021?

Louis Lehot- The State Of The Acqui-Hire In 2021: The Good, The Bad, The Why And What’s Next

Louis Lehot- Leaving Your Job? Don’t Forget Your Stock Options…

Louis Lehot- A Short Primer for Startups on Local Labor and Employment Law Compliance

Louis Lehot- How To Clean Up A Corporate Mess

Louis Lehot- Calculating And Paying Delaware Franchise Taxes — Startups Need Not Pani

0 notes

Text

Boeing Q&A: Staying on track despite pandemic disruption

https://sciencespies.com/space/boeing-qa-staying-on-track-despite-pandemic-disruption/

Boeing Q&A: Staying on track despite pandemic disruption

Ryan Reid spent more than two decades at Boeing before being promoted May 24 to lead its commercial satellite programs.

However, the pandemic brings fresh challenges for the space industry as COVID-19 continues to disrupt and delay critical supply chains.

These supply constraints threaten to hold back an exuberant satellite market that is rushing to meet surging demand for data, amid a flood of investor capital into satellite projects.

Ryan Reid, president of Boeing Commercial Satellite Systems International. Credit: Boeing

SpaceNews caught up with Reid on the sidelines of Satellite 2021 to learn more about how Boeing is managing this juggling act.

Can you give us a sense of how many satellite contracts are out for competing bids right now, and how that compares with previous years?

I would be probably making, at most, an informed guess on that because there’s a [specific] space that we target. I will say that there’s definitely a re-emergence of RFPs this year — and RFIs as well — where I’d say things have been a little quieter in the past couple of years. That’s encouraging to see.

Our customer engagement on the sales side has definitely picked up as well. Some of that is happening, of course, here at the [Satellite 2021] conference. But also ahead of the conference, meeting with customers virtually and, in some cases, meeting in person. It’s been exciting to see things starting to happen again, whereas in the GEO market it’s been a bit quieter over the past few years.

Do you see the industry returning to an average of 20 commercial GEO satellites a year?

I don’t see that happening. That was the long-standing bread and butter of the industry in the broadcast or DTH FSS markets. I think the GEO orbital slots are still the beachfront property, but I think it’s more repurposing those slots and shifting more toward network, data, and not seeing video broadcast or DTH as really growth markets.

I think we’re going to see different kinds of satellites emerge for those spots, but it’s not going to be 20-satellites-a-year … spread around the industry. We haven’t seen that in many years. I don’t anticipate that returning in that way.

Is that why we haven’t really seen many large export credit agency-backed satellite projects, even now that Ex-Im Bank has returned to full service?

When the Ex-Im Bank was kind of on pause, I certainly think that had an impact, but it may have been coincidental with shifts in the market, where a lot of the traditional operators, or I’d say regional operators, were in a situation where the market is changing and these players really needed to pause to look at where to make their next capital investments.

Is Boeing considering competing in the LEO marketplace?

Definitely, we have a non-fully integrated subsidiary, Millennium Space Systems, and they do a lot of work in LEO. I would look at it from the perspective of Boeing focusing on the technologies that are applicable for any orbit. We saw the marketplace transitioning to a data network system, so Boeing has put a lot of work into technology development that is really applicable at GEO, MEO and LEO.

Millennium Space Systems has a lot of expertise and history in the small satellite market. That positions us well to be able to work across whatever orbital regime. It really comes down to what problem or mission you’re trying to solve. Especially in the data market, some missions are well-suited for a network space environment, working across those orbital regimes.

For example, the core technologies we developed for 702X — fully software-defined payloads that we are applying to the O3b mPOWER system [in MEO], and have also applied to the wideband global SATCOM system [(WGS) in GEO] for the U.S. military.

About five years ago, Boeing applied for a license to deploy and operate a LEO constellation. What happened to those plans?

I can’t discuss that too much, but that’s still in play.

You’re still seeking partners?

As we’ve communicated before on that, we are continuing to look for partners, but there is work underway on that … I just can’t speak anymore publicly about it at this time.

Boeing is financially supporting Virgin Orbit’s plan to go public by merging with a special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC), which would raise capital for a constellation of IoT and Earth-imaging satellites. Does that put Boeing in front of the line to build them?

I can’t really comment on that. That’s a strategic investment that Boeing is doing but I’d probably have to refer you over to Virgin Orbit to discuss that.

Pandemic-related component shortages seem to be impacting the whole space industry. How are they affecting your business and what are you doing to mitigate that?

We’re certainly not immune to the impacts of the pandemic, and no pun intended on that. Throughout the pandemic we had well over half of our workforce still on site. There’s a lot of precautions that we took to make that happen and to make that work.

We were largely able to maintain our overall production and design efforts. There have been some supply issues that we’ve had to manage our way through. In this business, supply chain challenges are always something that needs to be worked through. It just might’ve been perhaps to a larger degree over the past 18 months.

Where we’ve had supply challenges through the pandemic, we’ve worked with our suppliers on workaround plans [and adjusting] the program plans and manufacturing schedules, etc., in order to accommodate those to keep our production and design work going, so that we can deliver it to the customers to the best of our ability.

Have these shortages affected the timing of the satellites that operators have ordered to clear C-band spectrum at all?

We’re still on track to delivering the C-band satellites that we’re building for SES right now. One of the main reasons that SES came to us for that was because they knew that we could provide a high confidence delivery schedule. Even through the pandemic, we are still on track to deliver on time.

What are some of the longer-term effects that COVID-19 has had on the industry?

I think one thing that we’ve all experienced is demand for a lot more data. It’s created a shift in how people communicate and how business is done, and all of that has increased the demand for broadband data. Where we see the market moving toward, and certainly where Boeing’s technology is focused, is on providing data and that broadband access from space.

Has it shifted demand for software-defined GEO satellites, versus traditional bent-pipe spacecraft?

I don’t know that I would say the pandemic has made that shift. I think, when you’re talking about needing to have data and network services, that naturally leads you to something that has the kind of flexibility that the software-defined satellites provide, which is why Boeing began investing in this technology many years ago. That has ultimately now come to fruition in the 702X product line.

Something that was well suited for DTH … was not going to lead you to the kind of efficiency and market flexibility that these networks systems really require.

We’ve been building digital satellites probably for well over 20 years. So we’ve always been on the leading edge of doing nontraditional analog satellites, really bringing digital processing into space. It’s always been the dream to make it fully software-defined, so you could change the orbital slot for a satellite, or the coverage area as traffic demand moves around throughout the life of the satellite — being able to just reprogram it, move the power, the bandwidth, change the shape of the beams, what have you. We achieved that with the 702X.

What can you say about the split between software-defined and bent-pipe satellites, and are we heading to a future where all GEOs are software-defined?

I sometimes struggle with ‘all or none’ questions. It depends on what kind of mission one wants to solve. But I think that we will see certainly see software-defined satellites. One of the reasons why Boeing has invested so much into the technology to realize this capability is because we really believe in a networked world, and in a data-centric world you need to have that kind of flexibility.

Bandwidth is such a precious resource. Having that fully software-defined flexibility allows you to maximize the value and the throughput that you can get from this really constrained resource.

What’s a trend in commercial space that people aren’t talking enough about?

I think we’re starting to see a trend that we saw in terrestrial telecom in the space industry, where operators that are transitioning into network service providers — so shifting away from just bandwidth or spectrum wholesalers into managed network service providers — are forming the same kinds of partnerships and business arrangements.

Think of your cellphone, you have an infrastructure that is almost ubiquitous and operators who may own some of those assets are partnering together to provide integrated services.

I think there’s going to be a lot more of that in the future as space turns into essentially an extended network. When we looked at the 702X, we really looked at the satellite as a Layer 2 network switch. It’s a very different way of thinking about satellites as part of the network infrastructure.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

#Space

0 notes

Link

This Nomilux Article gives detailed information on Special Purpose Acquisition Company(SPAC) in Luxembourg. For Details, Mail us at: [email protected]

#Establishing a SPAC in Luxembourg#Establishing a Special Purpose Acquisition Company(SPAC) in Luxembourg#Special Purpose Acquisition Company in luxembourg#Special Purpose Acquisition Company(SPAC) in Luxembourg#How much does it cost to start a SPAC?#How does a SPAC acquisition work?#Which structure is the most popular for SPACs?

0 notes

Text

SPACs, Part V: The Afterlife

We have one more post about SPACs today to explore the final phase of existence for these firms: what happens to a special purpose acquisition company after it acquires an operating company. Or, more simply — where do SPACs go after they die?

A fair number of them go into the software and tech sectors, apparently.

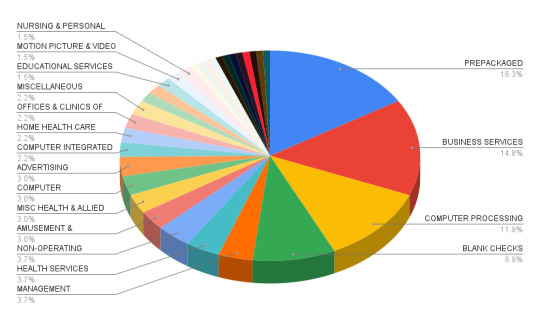

The crack Calcbench research team examined 135 SPACs to see what operating businesses they acquired, and what the balance sheets of those resulting firms looked like. Of those 135 firms, 22 “de-SPACed” into prepackaged software businesses and another 16 went into computer processing and data preparation.

Following a SPAC firm into the operating company beyond isn’t easy, because once the SPAC acquires the target, it ceases to exist. No longer do you have a ticker symbol or other standard identifier that would let an analyst follow the SPAC from its prior form into the new one.

But as a matter of standard procedure, Calcbench does assign a unique identifier to every registrant in our database, SPACs included. So we can follow along and see which operating companies today were SPACs in the past. By examining the resulting firm’s new SIC code, we can see which industries were most popular with SPACs as the SPACs acquired their way into operating company status.

Figure 1, below, is the breakdown for the 135 SPACs we studied. As you can see, the picture quickly gets messy. After prepackaged software, business services, and computer processing, most other industries have only a handful of SPACs entering their lines of work.

Where the Money Goes

We were also curious to see how de-SPAC transactions work in specific instances. So we looked at Diamond Eagle Acquisition Corp., which acquired both online sports betting company DraftKings ($DKNG) and sports betting technology firm SBTech at the same time in April 2020.

Prior to the acquisitions, Diamond Eagle had about $400 million in its coffers to make an acquisition. Executives there struck a deal to acquire DraftKings and SBTech at the end of 2019, and part of the deal included several institutional investors pumping another $304 million into the resulting public company in exchange for stock. That’s known as a PIPE deal (private investment in public equity) and they’re a common part of de-SPAC transactions.

The accounting for de-SPAC transactions, however, is tricky. Essentially, accounting rules treat DraftKings as the acquiring firm, which scooped up both Diamond Eagle and SBTech. So there is no purchase price allocation one can examine to see what the SPAC paid for DraftKings.

Rather, Diamond Eagle and the PIPE investors pumped a total of $704 million into DraftKings and SBTech, and the resulting public company had $1.82 billion in cash on the balance sheet at the end of 2020. (Up from only $76.5 million in 2019.)

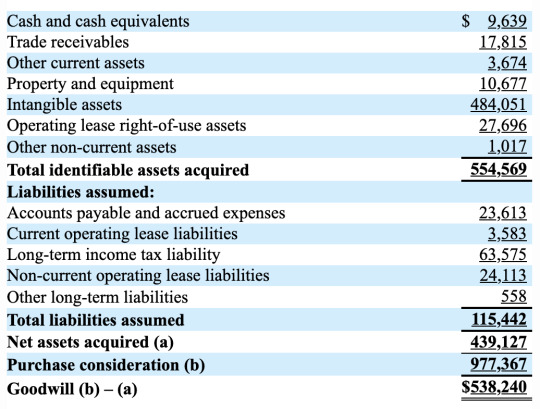

On the other hand, DraftKings also acquired that other business, SBTech — and we do have a purchase price allocation for that one. If you look at the Business Combinations disclosure that DraftKings included in its 10-K from May 3, you find this:

In other words, DraftKings (or Diamond Eagle and its PIPE investors, depending on your point of view) paid $977 million to acquire SBTech, and $538 million of that sum (55 percent) went to goodwill.

You can conduct similar research yourself using our Interactive Disclosures page to research business combinations, with some assistance from the Company in Detail page to analyze the balance sheet.

And if you want more information about tracing SPACs from their pre-acquisition life to post-acquisition existence as a new operating company, using our Calcbench identifier, just drop us a line at [email protected] and we’re happy to help you out.

0 notes

Text

Meet the New SPAC Circus Ringleader: The PIPE Investor

By: Louis Lehot

Since late 2019, when the special purpose acquisition corporation, or SPAC, returned to the public markets with a new twist, a circus of activity has breathed new life into the markets for privately-held emerging growth companies, forcing open a large window for public exits not seen in decades. In this “SPAC 2.0 boom,” sponsors of SPAC vehicles first raised large pools of blind capital in the public markets and then struck deals to buy emerging growth companies for ~10x the cash raised plus rollover equity and a second pile of cash in the form of a PIPE.

What is a PIPE, and why is it used for a de-SPAC merger?

“PIPE” stands for “private investment in a public entity,” often priced at a discount or containing a “sweetener” for the PIPE investor to make a more significant commitment than it would otherwise in the public market. The PIPE fundraising process happens after an LOI for a de-SPAC is signed, but before a definitive merger agreement, and is signed and announced concurrently with the latter. Then the SPAC and the target work together to prepare a joint registration statement and proxy filing on Form S-4 and seek SPAC stockholder approval, which requires the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to review and clear the de-SPAC transaction. Once the de-SPAC merger closes, the company files a resale registration statement to register the shares of common stock and warrants underlying the PIPE.

PIPE investors include investment funds, hedge funds, mutual funds, private equity funds, growth equity funds, and other accredited large institutional and qualified institutional buyers of publicly traded stock. The PIPE is well suited to complement the SPAC in a de-SPAC merger because of the speed of execution and because it does not require advance SEC review and approval.

SPACs have tapped PIPEs to bring in additional capital in a shorter amount of time to close de-SPAC mergers. Because of the nature of the SPAC process, there is often uncertainty surrounding the amount of cash that will be on hand following the merger. When combined with the SPAC proceeds in trust, the funds from the PIPE work together to provide liquidity for sellers and post-closing capital for the business to grow.

To be clear, in SPAC 2.0, the enterprise value of the target is so many multiples of the SPAC proceeds in trust that a PIPE has become ubiquitous to bridge the value gap. The Morgan Stanley data showed that on average, PIPE capital almost tripled the purchasing power of the SPAC, and for every $100 million raised through a SPAC, adding a PIPE added another $167 million.

Raising funds via a PIPE deal is comparable in some ways to an IPO roadshow in that there is a pitch to potential investors. However, PIPE deals are only open to accredited individual investors, and the share price is determined by reference to the de-SPAC merger valuation. When looking for PIPE investors in SPACs, targets look for high-profile names whose investment at a specified helps to validate the deal. This investment by well-respected investors can help to mitigate some of the risks that come with SPACs.

While PIPE deals are seen as an attractive option partly because they avoid many SEC regulations, all the attention SPACs have received, and their incredible spike in popularity has drawn the attention of regulators. This could mean additional regulations are on the horizon for both SPACs and PIPEs. But for now, these two continue to be an attractive combination for those looking to bypass the traditional IPO process.

What is SPAC 2.0 and why is the PIPE investor the ringleader?

SPAC 2.0 was essentially the cash in the SPAC vehicle combined with a new private fundraiser in the form of a PIPE merged into a privately-held emerging growth company. The resulting party for SPAC IPOs, de-SPAC transactions, and even traditional initial public offerings, or IPOs, continued through the end of the first quarter of 2021, with hardly even a little intermission for the first COVID lockdown. According to data compiled by Morgan Stanley, in 2020, PIPEs generated $12.4 billion in additional funding for 46 SPAC mergers.

The SPAC 2.0 structure had something for everyone:

-the emerging growth company got a public exit without having to go through a traditional IPO

-the emerging growth company stockholders got a snap spot-valuation based on three-year out financial projections not available in conventional IPOs

-the emerging growth company got a public acquisition currency in the form of listed stock, validation in the public markets via the stock exchange listing, and cash to the balance sheet to power growth

-stockholders in the emerging growth company could negotiate for some amount of immediate liquidity

-stockholders in the emerging growth company got long-term liquidity via the public trading market

-SPAC stockholders and PIPE investors got access to emerging growth companies that weren’t otherwise going public

-SPAC sponsors made their “carry” in the form of 20% of the equity in the SPAC (pre-dilution) plus warrants in some cases and a path to liquidity with a short lock-up period

-SPAC sponsors could rent out their names, network, and prestige and get a quick exit

While in SPAC 1.0, the SPAC sponsors would take over the target and operate it like a private equity buyout fund for long-term capital growth, in SPAC 2.0, the SPAC sponsors are like bankers, raising capital and then handing over the keys to management of the emerging growth company in exchange for a commission.

But the lights went out for the SPAC party in April 2021 when President Biden appointed a new chair to lead the Securities and Exchange Commission. Upon taking office, new SEC Chair Gary Gensler effectively closed the market for SPACs by announcing a compliance review, putting long-standing SEC policy and rule interpretations in doubt. Transaction participants reported that SEC staffers reviewing their pending transactions started asking questions, requesting changes, and appeared in no hurry to clear pending “de-SPAC” deals.

The market for new issues froze up, and the demand for de-SPAC transactions ground to a halt. The trading index for recently “de-SPAC’ed” public companies dropped double-digit percentage points. Investors started to lick their wounds.

When the SEC began clearing SPAC mergers again in early summer 2021, it was not as simple as just turning lights back on and taking its foot off the brakes. That is because PIPE investors, who provide fresh capital to the company that is merging with a public SPAC vehicle (commonly referred to as a “de-SPAC transaction”), have taken their place as the new ringleaders at the SPAC circus. The amount of capital PIPE investors are willing to put into a de-SPAC transaction at a given valuation and what sweeteners have become the deciding factor as to whether a de-SPAC transaction can get done.

PIPE investors no longer accept transaction terms as proposed and have started to make new commitments contingent on adjusted valuations, redemptions of SPAC sponsor promote securities, and better alignment to create better after-market trading conditions. Knowing what PIPE investors want and how much they will pay has become the new ticket to success in the SPAC market. This makes the PIPE investor the new ringleader in the SPAC 3.0 cycle.

Article originally published on Louis Lehot Official Medium.

About the Author:

Louis Lehot is an emerging growth company, venture capital and M&A lawyer at Foley & Lardner in Silicon Valley. Louis Lehot spends his time providing entrepreneurs, innovative companies, and investors with practical and commercial legal strategies and solutions at all stages of growth, from garage to global. Louis Lehot focuses his efforts on technology, digital health, life science and clean energy innovation. Louis’s clients are public and private companies, financial sponsors, venture capitalists, investors and investment banks, and he has helped hundreds of companies at formation, obtaining financing, solving governing challenges, going public and buying and selling. Louis Lehot is praised by clients, colleagues and industry guides for his business acumen, legal expertise and leadership in Silicon Valley.

Connect with Louis Lehot:

Website: Louis Lehot

Website: Louis Lehot

Chambers: Louis Lehot

LinkedIn: Louis Lehot

Facebook: Louis Lehot

Twitter: Louis Lehot

Instagram: Louis Lehot

YouTube: Louis Lehot

Vimeo: Louis Lehot

Pinterest: Louis Lehot

Ello: Louis Lehot

Magazine Xpert: Louis Lehot

Crunchbase: Louis Lehot

Muckrack: Louis Lehot

Anchor.fm: Louis Lehot

Ideamensch: Louis Lehot

Chief Executive: Louis Lehot

Data Driven Investor: Louis Lehot

Good Men Project: Louis Lehot

Speaker Hub: Louis Lehot

Read the Articles written by Louis Lehot:

Louis Lehot- What to expect for seed and pre-seed stage financing in 2021

Louis Lehot- A Brief Legal Guide To Buying And Selling Shares Of Private Company Stock

Louis Lehot- The IPO Markets Are Changing, And So Is The Lock-up Agreement

Louis Lehot- What are SPACs, and how they are different from IPOs?

Louis Lehot- L2 Counsel Represents AgTech Leader FluroSat In Dagan Acquisition

Louis Lehot- Considering Selling Your Company? Be Clear on Your Fiduciary Duties

Louis Lehot- Incentivizing With Stock Options: What Your Startup Needs To Know About ISOs, NSOs And Other Parts Of The Alphabet Soup

Louis Lehot- Ready To Sell Your Startup In 2021?

Louis Lehot- The State Of The Acqui-Hire In 2021: The Good, The Bad, The Why And What’s Next

Louis Lehot- Leaving Your Job? Don’t Forget Your Stock Options…

Louis Lehot- A Short Primer for Startups on Local Labor and Employment Law Compliance

Louis Lehot- How To Clean Up A Corporate Mess

Louis Lehot- Calculating And Paying Delaware Franchise Taxes — Startups Need Not Panic

0 notes

Text

In Focus: Lordstown Motors, We Wanted It So Bad

In 2003, when the average price of gas was $1.59 per gallon, two guys, Marc and Martin started an electric car company. The following year Marc and Martin connected with an investor named Elon. Two other members, Ian and J.B. would join and make up the founding team of the new electric car company.

Fast forward five years and Elon, the investor, is in full control, and the original two founders Marc and Martin have left the company. The company eventually goes on to become the biggest thing in electric vehicles and the company we all know and love today, Tesla.

Many people aren't aware that Tesla lost its original founders in 2008. Elon Musk has become Tesla, and so today people associate everything Tesla to Elon Musk. But Tesla had its moment where its founders stepped away, and left the investor in charge. Which causes me to wonder, could Lordstown Motors (RIDE) follow in Tesla's footsteps and make what seems like a rough time for the company just a speed bump in its overall history?

Last week Lordstown's CEO Steve Burns and CFO Julio Rodriquez stepped down from the company. The news was the cherry on top of a bad 2021 for Lordstown.

In March Hindenburg Research released a report claiming that Lordstown had misled investors on their production capabilities and the demand for the company's electric truck. According to the Hindenburg report, former employees claim that a Lordstown electric vehicle is several years away from happening. In addition Hindenburg pointed out that the purchase commitments that Lordstown had touted for their Endurance truck were not firm commitments.

After spending months denying the Hindenburg Research report, Lordstown announced in early June that the company has limited capital which would force them to produce half the vehicles originally forecasted by the company . Now add to that the CEO and CFO resigning, and as you can see, it has not been a very good 2021 for Lordstown.

What's Next?

The latest news from Lordstown is that the company has enough cash to last until next May and that production of the Endurance electric truck will start this September. It's decent news to investors, but nothing to write home about after now knowing that those pre-orders that were once celebrated by the company weren't firm commitments to buy. Assuming thatthe Endurance does go into production in September and it turns out to be everything that Lordstown says it will be, it will still take some time after production for the word to spread, which means the company still needs more cash.

Industry analyst Joseph Spak of RBC Capital Markets believes Lordstown needs $2.25 billion between this year and 2025 to remain solvent. Spak presumes the company will get the cash it needs through either government funding or by issuing additional equity. Both options at this point should be in the electric vehicle startup playbook.

Tesla sold new shares to the market twice in 2020. 17 years after the company started, and with thousands of cars produced and on the road it still raised money through issuing additional equity. Andlet's not forget the $465 million loaned to Tesla by the Obama administration back in 2009. The amount pales in comparison to the $50 billion the government loaned GM, but at the time Tesla had sold less than 1,000 vehicles. The loan would be a big catalyst for Tesla's future success.

For Lordstown the only way out of the mess is goingthrough the mess, and the person tasked with leading them temporarily out of the mess is Angela Strand. Strand's resume regarding all things electricis impressive. She co-founded Chanje, a joint venture between Smith Electric Vehicles and FDG Electric Vehicles Ltd, she founded another electric based company In-Charge. She also served as Vice President at Workhorse for a time.

By Strand's side on the management team there's Lordstown's president Rich Schmidt, who previously served as Tesla's Director of Manufacturing Operations between 2012 and 2017, so he's seen some tough times in the electric vehicle business. There's also John Vo, Lordstown's Vice President of Propulsion. Vo served as the Head of Global Manufacturing for Tesla from 2011 to 2017, he's another Lordstown exec who's seen tough times in the EV industry. Finally, Darren Post Lordstown's V.P of Engineering led five new vehicle programs from concept to production while at GM.

The management appears to be familiar with setbacks as well as success, so this current issue shouldn't have anyone on the management team very rattled. The question that investors have to ask themselves though is can this management team execute if they're able to raise the funds they need?

We Wanted It So Bad

Since hearing its former CEO speak about how EV companies prior to Lordstown were only going after the weekend warrior truck owner and not the everyday workman and woman, I was hooked on Lordstown's vision. After seeing the Cybertruck and Nikola's Badger my question was how do the people I know use those trucks to work in? The contractors, the pool service people, and lawn care people, the diving instructors I know need a truck that's functional, not one that just turns heads, and that's what Lordstown promised, a functional electric work truck.

However, what I and many investors who were caught up in Steve Burns' dream forgot was that starting an automobile company is extremely hard. Elon Musk once wrote there are onlytwo American automakers that haven't gone bankrupt, that's Ford (F) and Tesla. It's an extremely difficult business to maneuver, and yet when investors saw an EV company making themselves public we all bought in hoping that it would be the next Tesla.

Tesla's stock price run from $42.12 per share (adjusted for the five-for-one stock split) in 2019 to over $300 per share in August 2020 when it announced its five-for-one stock split hypnotized us all. All of us who missed out on owning Tesla for less than $20 a share in 2011 were hoping Lordstown could be our cheap buy-in to the growing electric vehicle market. We wanted and expected all of the good of Tesla, but never once stopped to consider the bad that Tesla had to endure to get to where they are today.

Following Tesla since 2010, I've seen how close it's come to not making it, and because it did make it I assumed that the path it laid out would be what future EV companies would follow to make the travel from startup to established auto maker less strenuous. But Lordstown wasn't looking to walk in Tesla's shadow, it was looking to create and sell its own technology to a commercial market, and in doing so it was starting from zero and carving out its own path.

I don't know if I'm still in love with Steve Burns' vision or I'm just a hopeless optimist, but I'm still a believer. Right now Lordstown's management nor its investors can think about winning the game, the focus now should be on staying in the game.

I can't think of any manufacturing company that hasn't gone through a financial crisis at some point in their start. I expect all of the startup electric vehicle companies to go through it at some point or another, minus Rivian, who seems to just keep raising money. In 2019 Rivian raised over $2 billion and in 2020 raised another $2.5 billion. According to Business Insider Lordstown received $675 million upon going public by way of a SPAC acquisition.

Also, as amazing as Ford's electric F150 looks, I'm still not convinced that Ford is all in on electric vehicles, and because of this I think the electric commercial truck / fleet truck market is still up for grabs.

Investing in Lordstown is a big leap of faith. Based on all that has been revealed, I think the company should trade at a lower valuation than it currently trades at right now ($1.88 billion). However, with the right CEO and funding this company could be the next big thing in electric vehicles, and then we'll be paying a lot more than $1.88 billion for the company.

My thoughts still go back to the commercial vehicle / fleet vehicle market. Precedence Research valued the commercial vehicle market at $1.51 trillion in 2019, and it expects the market to grow to $2.55 trillion by 2027. I pass so many fleet vehicles on my daily runs, and I know that one day those trucks are going to be electric, and I wonder who will those electric trucks be made by? The market offers a lot of room for a quality electric truck company to grow, but first, Lordstown has to stay in the game.

#ElectricVehicles#Stocks#StockMarket#Investing#Investments#WallStreet#Investment Education#FinancialEducation#LordstownMotors#Tesla#Ford#GeneralMotors#GrowthStocks#Endurance#F150

0 notes

Photo

3 risk trends for the post-COVID economy

During the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses in every sector have faced unprecedented challenges and risks. Almost overnight, companies had to move employees online, alter products, offer new services, implement extensive safety protocols, and come to terms with the possibility of a complete shutdown. This pivot to the “new normal” dramatically altered risk profiles and insurance needs.

Now, with vaccine rollouts underway and many states lifting health restrictions, businesses are feeling optimistic about a future free from the pandemic. But even with herd immunity, we won’t go back to a pre-COVID world.

Now over a year into the pandemic, COVID-19 has sparked a lasting shift in how we do business. The pandemic transformed our business landscape in terms of the way we work and how we evaluate risk. In this article, we are diving into three risk trends to keep in mind as we transition into post-COVID economic recovery.

3 trends in the post-COVID risk landscapeM&A activity sparks financial market volatility

Just after the pandemic started, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) experienced a decline as companies shifted their focus to keeping operations going. According to White & Case, an international law firm, the final quarter of 2019 saw a 77% increase in M&A deals, for a total of more than $540 billion. And “the valuations of these M&As are going up dramatically,” says David Perez, chief underwriting officer of Global Risk Solutions at Liberty Mutual Insurance.

The use of special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) has also changed the M&A landscape, with a trend toward businesses relying on these companies instead of private equity firms. As public corporations listed on the stock exchange, SPACs sole function are to acquire private companies. When a SPAC acquires a company, it avoids the need for a traditional IPO.

The final quarter of 2019 saw a 77% increase in M&A deals, for a total of more than $540 billion.

What does this mean for the market? According to Perez, SPACs have made the market significantly more volatile. “We’ve seen swings of 1,000 points from month to month,” he says, “and that heightens D&O risk.”

“From an insurance perspective, you’re underwriting the company raising the capital, but you don’t always know what company they’ll actually acquire. That leaves a wide range of potential risks to contend with,” says Perez.

Many businesses rely on M&A to grow – and this isn’t a bad thing. But if your business’s growth strategy includes plans for a merger or acquisition, especially by a SPAC, you need to look closely at risk and ensure you have adequate coverage. In hardening insurance markets, like the market for directors and officers (D&O) coverage, collaborating with underwriters is essential to help protect your company during these periods of transition.

A deconditioned and/or untrained workforce drives safety risks

In 2020 and 2021, millions of Americans decided to retire early – often due to the struggle to adapt to remote work, or unexpected job loss. Similarly, McKinsey & Company recently reported that COVID-19 may force up to 25% of U.S. workers to change occupations. This means that as employers recover financially and look to build up their staff in the coming years, they may be looking at a less-skilled or untrained pool of applicants – and that introduces more risk.

“In any job with a high safety risk, like construction, trucking, or manufacturing, untrained workers present tremendous exposure for accidents to occur. A spike in incident frequency and/or severity is probably our biggest concern as economies reopen,” says Perez.

COVID may force up to 25% of U.S. workers to change occupations. So as employers recover financially and look to build up their staff in the coming years, they may be looking at a less-skilled or untrained pool of applicants — and that introduces more risk.

In labor-intensive industries like manufacturing or construction, there’s also a new risk of injury because of deconditioning. Working from home – or not working at all – for more than a year has left many workers with less endurance, flexibility, and strength, according to EHS Today. And those physical changes equate to greater risk of injury on the job.

To address the increased risk of injury from untrained or deconditioned employees, Perez recommends investing in training. “The number one best practice is making sure you have procedures and protocols in place to get your workers trained up appropriately,” he notes. “The more hazardous the occupation, the more time you should allow for the hiring and training process to occur.”

Heightened social responsibility for corporations

A year of dealing with the pandemic didn’t just shift how businesses think about health and safety. Social unrest also shifted how they think about diversity, equity, and inclusion. Committing to environmental and social governance (ESG) is more important than ever – but it also introduces more risk, as consumers demand higher levels of accountability and corporate responsibility.

“Environmental and social governance (ESG) is something that investors are concerned with as well as customers,” says Perez. “Financial institutions are increasingly required to disclose their corporate social responsibility efforts and falling short will be treated much more harshly both in the court of public opinion and in the actual jury box.” Bottom line? Ignorance is no longer an excuse for businesses engaging in unethical or unjust practices

Meeting ESG guidelines can be labor-intensive, as both insurers and insured parties take a closer look at their investment portfolios, vendors, suppliers, and partners. “The insurance industry is going to become a bigger leader, overall, in terms of helping customers manage the transition while recognizing that the importance of ESG in not only the investment side of the house, but also the underwriting side of the house,” says Perez. “Making sure that we’re committed as an industry to ESG is going to be more important every day, every year, going forward.”

Evaluating risk in an uncertain world

While COVID-19 has brought turbulence to the marketplace, there is one certainty: when the pandemic finally subsides, it won’t be a return to “business as usual.” Not only has work culture permanently changed because of the pandemic, but the ongoing hard markets will add additional difficulties for many companies. Companies looking to reduce their risk should work with an insurance provider to help them understand their specific risks in a volatile financial landscape and offer resources and coverage to fit those needs.

For Perez, addressing those challenges is an ongoing priority. At Liberty Mutual, “We continually push education out to the marketplace, providing updates on exposures, risk control measures and legislative changes. We want all of our customers to be informed,” he says.

The future may be uncertain but taking a proactive approach to risk management can help you stay ahead of the curve and avoid rate changes in a fluctuating insurance market. “In general, there’s still a lot of correction that needs to be worked out in the marketplace,” says Perez. “Our goal is always to help clients navigate uncertainty as smoothly as possible by bringing our knowledge and underwriting expertise to bear.”

0 notes

Link