#How to Lose Everything In Politics (Except Massachusetts)

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Saturday was Joe Biden’s first-ever win in a presidential primary or caucus. It was an awfully big one: Biden won South Carolina by nearly 30 percentage points over Bernie Sanders. And it made for one heck of a comeback: Biden’s lead over Sanders had fallen to as little as 2 to 3 percentage points in our South Carolina polling average in the immediate aftermath of New Hampshire.

What explains the big swing back to Biden in South Carolina? And what does it mean for the rest of the race — and in particular for Sanders, who had entered this weekend as the frontrunner?

Here are five possible explanations — ranging from the most benign for Sanders to the most troubling for his campaign.

Hypothesis No. 1: This was a “dead cat bounce” for Biden because voters were sympathetic to him in one of his best states. It may have been a one-off occurrence.

Remember Hillary Clinton in New Hampshire in 2008? Left for dead by the national media after she lost Iowa to Barack Obama in 2008, she overcame a big polling deficit for an upset win in the Granite State. It didn’t do her much good, though; she won Nevada the next week but badly lost South Carolina two weeks later, eventually losing the nomination to Obama.

There are some similarities to Biden’s position in South Carolina. Like Clinton before New Hampshire, the media all but counted him out of the running after Iowa. Like Clinton in New Hampshire, Biden had a strong debate a few days before the primary along with some emotional moments on the campaign trail. Furthermore, some of the reporting from South Carolina suggests that certain South Carolina voters — especially older whites and African-Americans — felt deep loyalty toward Biden and wanted to keep him in the running.

Degree of concern for Sanders if this hypothesis is true: Low to moderate. If this were truly just a one-off sympathy bounce, then Sanders can live with it. Sure, Bernie missed an opportunity to put the race away with a win — or perhaps even a close second — in South Carolina. But voters rarely just hand the nomination to you without creating a little bit of friction. But if voters in other Super Tuesday states feel the same way that South Carolinians did, the sympathetic moment for Biden may not be over yet.

Hypothesis No. 2: The disparate results so far are simply reflective of the geographic and demographic strengths and weaknesses of the candidates. The notion of “momentum” is mostly a mirage.

If this is the case, you could wind up with a very regionally-driven primary, with Biden doing well in the South but perhaps not so well everywhere else. This is more or less what our model expects to happen, for what it’s worth; it now has Biden favored in every Southern Super Tuesday state except Texas, and he’s an underdog everywhere outside of the South.

The counter to this: Biden clearly did much better in South Carolina counties and precincts that weren’t as emblematic of his base than he had in those kinds of districts in other states. The counter to the counter: Geographic factors pick up a lot of information that demographics alone miss. So his strong performance in certain parts of South Carolina may bode well for how he’ll do in Alabama or North Carolina or Georgia. It may not say much about his performance in Michigan or California, however.

Degree of concern for Sanders if this hypothesis is true: Low to moderate. Sanders led Biden by about 12 points in national polls heading into South Carolina. Moreover, our model — which uses demographics in its forecast — has Sanders ahead. So although Biden has some strong groups and regions, Sanders’s coalition looks as though it’s slightly bigger and broader overall — although a post-South Carolina bounce for Biden or swoon for Sanders could eat into that advantage.

Hypothesis No. 3: The party is finally getting behind Biden. It may or may not work.

Almost half of South Carolina primary voters said that Rep. James Clyburn’s endorsement of Biden was a big factor in their decision. There are some questions about the cause and effect: It may be that Biden voters were pleased with the endorsement and said it was a major factor, even though they were planning to vote for Biden already. Still, Biden did get a big, late surge in the polls following the debate and the endorsement.

Clyburn is also one of the few party bigwigs to have endorsed a candidate. While lots of U.S. representatives, mayors, lieutenant governors and so on have endorsed, not many senators, governors or party leaders have. That leaves open the possibility there could be a surge of endorsements for Biden in the coming days. He’s already scored several major endorsements in Virginia, for instance, which is a Super Tuesday state.

Degree of concern for Sanders if this hypothesis is true: Moderate. The “Party Decides” view of the race treats endorsements and other cues from party leaders as being highly predictive and important. And a surge of endorsements for Biden seems reasonably likely. This could reverse a longstanding period of seeming indifference by party leaders toward Biden as they hoped for Michael Bloomberg or some other alternative to emerge.

But it’s not clear how effective an endorsement surge would be, as few legislators command the respect in their states that Clyburn does. Moreover, although we’re not going to cover it at length here, there’s plenty of room to question how empirically accurate the “Party Decides” is. Meanwhile, endorsements aren’t necessarily what Biden needs; an influx of cash would do him more good.

Hypothesis No. 4: Voters are behaving tactically. Biden was the only real alternative to Sanders in South Carolina, and he may be the only real alternative going forward.

Tactical voting is something you hear a lot about in multi-party systems like the United Kingdom’s, where voters are trying to find the most viable candidate from a number of similar alternatives (for example, from among the various parties that opposed Brexit). The same dynamics potentially hold in multi-candidate presidential primaries, and we’ve already seen evidence of it. In New Hampshire, voters flocked to Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar in the closing days of the campaign and away from Biden and Elizabeth Warren. In South Carolina, tactical voting may have worked in Biden’s favor, instead. Biden was fairly clearly the most viable alternative to Sanders, so voters for candidates like Tom Steyer and Buttigieg may have gravitated toward him in the closing days of the campaign.

Degree of concern for Sanders if this hypothesis is true: High. First, if voters are actively looking for alternatives to Sanders — but just can’t settle on which one is best — that can’t be good news for him, and gives some credence to the “lanes” theory of the race in which the moderate vote could eventually consolidate behind one alternative to Sanders. The South Carolina exit poll had Sanders’s favorability rating at just 51 percent, which is some of the stronger evidence for a ceiling on his support so far.

Moreover, Biden’s strong finish in South Carolina, along with improved debate performances, endorsements, and increasingly favorable media coverage, could make it clear to voters that Biden is the best alternative to Sanders after all, possibly with some exceptions where there are home-state alternatives (Klobuchar in Minnesota and Warren in Massachusetts). If Biden picks up support from tactical voters who had previously backed candidates such as Bloomberg and Buttigieg in polls, that could lead to a larger-than-usual South Carolina bounce.

Hypothesis No. 5: There has already been a national surge toward Biden that is not fully reflected in the polls.

It didn’t get much notice, but polling outside of South Carolina was also pretty favorable to Biden toward the end of last week, including polls that showed sharp improvements for him in states such as Florida and North Carolina. He’s also gotten better results in some national polls lately — climbing back into the low 20s — along with other, not-so-great ones.

The data isn’t comprehensive enough to know for sure. Between the dense cluster of events on the campaign trail (primaries, debates, etc.) and the different races that pollsters are surveying (South Carolina, Super Tuesday, national polls), everything is getting sliced pretty thin. But we do know that Biden made big improvements since the debate in South Carolina polling, the one state where we did have enough data to detect robust trendlines.

Degree of concern for Sanders if this hypothesis is true: High. Suppose that Biden gained 5 or 6 percentage points across the board nationally and in Super Tuesday states as a result of this week’s debate (or other recent factors such as voters’ reaction to coronavirus), but it’s gone largely undetected because there hasn’t been enough polling. If that’s the case, then Biden may already be in a considerably better position than current polling averages and models imply — and then he could get a further bounce from winning South Carolina on top of it. This is a scary possibility for Sanders, and although there isn’t enough data to prove it, there also isn’t much that would rule it out.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ranking Little Women.

“This is a film not about a single woman’s quest for identity or independence, but about the infinite power of a woman’s community.”

Letterboxd is humming with Little Women Cinematic Universe energy, particularly since the trailer for Greta Gerwig’s new version, with its cast pulled straight from the Letterboxd Year in Review, dropped.

“I have a guttural five star type of feeling after the trailer,” writes Leia. “Bi culture is thirst-watching this for Timothée Chalamet and Florence Pugh,” Raph enthuses.

Yeah, we see you watching and re-watching all the previous film adaptations of Louisa May Alcott’s landmark 1868 novel that you can fix your eyeballs on. We’re not ones to doze by the fire; we like adventures. So let us take you on a romp through past Little Women screen adaptations, in which we rank the productions based on our community’s stantastic response to each.

From left: Milton, Daisy & Ruby.

Little Women (1917)

Directed by Alexander Butler

Though the March family lived in the town of Concord, Massachusetts, it was the British who got to the beloved American book first, with this silent film adaptation.

Starring Ruby Miller as Jo March and musical-comedy star Daisy Burrell as Amy March, the film is considered lost, so nobody on Letterboxd will ever be able to confirm how the prolific English actor Milton Rosmer stacked up as rich-boy-next-door Theodore ‘Laurie’ Laurence.

Letterboxd ranking: #7.

Conrad Nagel & Dorothy Bernard.

Little Women (1918)

Directed by Harley Knoles, screenplay by Anne Maxwell

Also considered lost is the first American adaptation, by the brilliantly named Harley Knoles, a British director who spent the 1910s working in the US. Matinee idol Conrad Nagel played Laurie.

Letterboxd ranking: #4. Jo March was played by silent film queen Dorothy Bernard, whose father hailed from New Zealand (as does Letterboxd), therefore this version ranks highly even though there are no Letterboxd ratings or reviews to confirm this fact. Instead, check out D.W. Griffiths’ dark, march-across-the-desert film The Female of the Species, in which “only Dorothy Bernard gives a believable performance” according to Michael.

(An aside: Here’s a list of unseen silent films that actually do exist, but that nobody on Letterboxd has yet seen, apparently.)

From left: George Cukor directs Katharine Hepburn, Joan Bennett, Frances Dee and Jean Parker in ‘Little Women’ (1933). / Photo courtesy MGM

Little Women (1933)

Directed by George Cukor, screenplay by Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heerman

Now we’re getting to the meat & potatoes of Little Women standom. Not that it’s a competition, but Katherine Hepburn is the one Saoirse Ronan needs to beat. Hepburn set the screen standard for gutsy portrayals of Jo March, and appropriately so in this first version with sound because let’s be honest, when the world got to hear Jo March speak those lines aloud for the first time, Hepburn’s voice was the perfect choice.

The prolific Cukor was nominated for the best directing Oscar (he eventually won one in 1964 for My Fair Lady), but it was the screenwriters, married couple Mason and Heerman, who won the Academy Award for their script. (Hepburn also won that year, but not for playing Jo March.)

Letterboxd ranking: #3. “A true gem of depression-era cinema,” writes Taj. “Every single scene in the first half of this film is a pure delight.”

“I’d like to personally thank Katharine Hepburn for being absolutely perfect,” writes Skylar. Morgan concurs: “Hepburn plays Jo with a rough physicality, bold confidence, and a gentle sensibility, standing out in a rather unremarkable movie.”

June Allyson and Rossano Brazzi.

Little Women (1949)

Directed by Mervyn LeRoy, screenplay by Sally Benson, Victor Heerman, Sarah Y. Mason, and Andrew Solt

Why re-write a script that’s already perfect? Mervyn LeRoy’s 1949 Technicolor update lifted most of the screenplay and music from Cukor’s version, throwing in an on-trend acting line-up of June Allyson (Jo), Janet Leigh (Meg), Elizabeth Taylor (Amy) and Margaret O’Brien (Beth).

Never mind who played Laurie in this version (okay, okay, it was hunky Rat-Packing socialite Peter Lawford); the real tea here is the American film debut of Bologna-born Italian great Rossano (The Italian Job) Brazzi, as Professor Bhaer.

Letterboxd ranking: #2. “This is the best Little Women, fight me,” DylanDog declares. “I’m so impressed by the fact that they rewrote/restructured/padded out the 1933 screenplay, assembled a nearly pitch-perfect cast, and made such a fantastic Technicolor remake,” Dino reasons. “We actually see way more of the novel’s subversive gender politics play out here, and Jo’s motivations are much more palpable.”

“Although I also really like the 1933 version, the Hepburn film lacks the warmth I do find in the 1949 adaptation,” Annewithe writes. “I feel that this version conveys the true spirit of the book and is as cozy and warm and loving, and it’s in colour!”

Susan Dey and William Shatner.

Little Women (1978)

Directed by David Lowell Rich, screenplay by Suzanne Clauser

Between 1949 and 1994, all we got was this seventies miniseries adaptation, which flies far under the radar of Letterboxd’s Little Women obsession with only two member reviews.

Susan Dey was a smart choice to play Jo March, given her Partridge Family profile at the time, while Meredith Baxter Birney, who played Meg, went onto huge sitcom fame as Michael J. Fox’s mom in Family Ties. The real curiosity factor here, writes LouReviews, is “the casting of one William Shatner as the Professor, and he’s rather good!”.

Letterboxd ranking: #6. “This story keeps moving me,” is all Sandra had to say, while LouReviews writes “not essential by any means, but if you like the novel, you'll want to see this”.

Winona Ryder and Christian Bale.

Little Women (1994)

Directed by Gillian Armstrong, screenplay by Robin Swicord

It only took 126 years from publication for a woman to get behind the camera of a Little Women film, despite Alcott’s masterpiece long being a prime example of (white privileged) female complexity in storytelling. (Although, it’s fair to note that women have been involved in the scriptwriting for every Little Women film adaptation that we know of.)

Released—as Gerwig’s 2019 update will be—at Christmas, Gillian Armstrong’s version was as star-studded as they come, with 90s it-girl Winona Ryder—fresh off Reality Bites—as Jo March, and Christian Bale as Laurie. Also: Kirsten Dunst, Samantha Mathis and Eric Stoltz, with Susan Sarandon as Marmee.

Letterboxd ranking: #1. Sydney writes: “It’s really tough dealing with the fact that this movie is probably never going to get the respect it deserves.” Well Sydney, we’re happy to make your day. This Little Women is currently the highest-rated on Letterboxd (except for Bale’s facial hair, which is not highly rated by anyone). Thomas Newman’s score is much beloved, and the film is, in Julia’s opinion, “the definitive adaptation!”.

On a recent re-watch, Lauren “was transported back in time to my childhood and for those two hours everything felt simple and safe.” Meanwhile Sally Jane Black, in a thoughtful piece, gets right to the heart of Little Women-love: “This is a film not about a single woman’s quest for identity or independence, but about the infinite power of a woman’s community.”

Little Women (2017)

Directed by Vanessa Caswill, screenplay by Heidi Thomas

Not strictly a film, but well worth a mention, this recent three-part BBC adaptation stars Thurman-Hawke offspring (and Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood flower child) Maya Hawke as Jo March. Emily Watson plays the March matriarch, and—Gerwig connection alert!—Kathryn Newton (Lady Bird’s Darlene) is Amy March.

Letterboxd ranking: #5. Alicia is a fan: “Winona will always be my Jo, but Emily Watson absolutely kills it as Marmee! Just love her FACE!!!! Her pain is your pain; her joy is your joy. Oyyy!”

Bethchestnut was slowly convinced: “A very handsome and loving production, even if there were a lot of things that bothered me about it. Doesn’t help that I watch the 90s version every year. Still made me cry twice.”

Little Women (2018)

Directed by Clare Niederpruem, script by Clare Niederpruem and Kristi Shimek

Released to mark the novel’s 150th anniversary of publication, this version wins points for casting Lea Thompson (Howard the Duck, Back to the Future) as Marmee, but loses points for the weird contemporary update, in which the March sisters inexplicably lose the messy complexity of their far more adventurous 19th-century selves.

Letterboxd ranking: #8. “Who decided casting Ryan from High School Musical was a good idea?” asks Sue.

Also worth seeking out: two different Japanese anime adaptations, the 1981 series Little Women’s Four Sisters (若草の四姉妹), and the 1987 series, Tales of Little Women (愛の若草物語), which aired on HBO in 1988 and is notable for writing in a black character. Not worth a mention: this 1970 TV adaptation.

Greta Gerwig’s ‘Little Women’ opens in cinemas this December.

#little women#greta gerwig#timothee chalamet#saoirse ronan#florence pugh#meryl streep#winona ryder#katherine hepburn#letterboxd

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of my thoughts on the thing.

I’m feeling mostly good about the election. Not great, but not bad, and nothing like The Day After in 2016. Regardless of how you slice it, we’re in a better position today than we were yesterday, even if some of our preferred candidates lost, or our preferred narratives didn’t fully pan out.

I’ll start with the bad. Apparently my moving to a GOP district did not magically flip it blue, which is a bit surprising but OK, whatever. Katie Porter lost, and this is the biggest disappointment of the night for me (I think?) because this district was actually winnable. Mimi Walters, the incumbent, is an uncharismatic, do-nothing who rubber-stamps her party line without fanfare. This county, if not the district, is now majority Democrat, and this election was a chance to rebuke the past two years of Republican governance. But Katie Porter lost, and I think she lost because she ran a bad campaign. I saw very few Porter signs on the streets (and the streets here are FILLED with signs around election time); I knew nothing about what Porter actually stood for (I just found out this morning she supported repealing the gas tax!); and she cancelled on multiple in-person events during the primaries and general. Now, maybe all of her resources were spent in more conservative parts of the district, I don’t know, but I do know that I got multiple people knocking at my door over the past few days, in an ivory tower neighborhood literally filled with liberal professors, asking me to vote for Katie Porter, which seems like misspent energy to me.

Oh well, there’s always 2020.

The senate is a tough loss, especially Heitkamp and very especially McCaskill. But despite media narratives to the contrary, the senate was always an extreme long-shot for the Democrats. The map and schedule were historically difficult, and the fact that Beto actually got within a few points in a race that started out with about a 20 point difference is extraordinary. Sure, it would have been great to take the senate, and it sucks that there are now fewer Dems in the senate than before, but in terms of actual legislative power etc., there’s not really any difference from the status quo. Now the Dems will lose by a slightly higher margin. But at least there’s a check in the House.

Florida and Georgia are bad. And in both cases there’s some electoral irregularities, along with outright vote suppression. Democrats absolutely must make voting access — and gerrymandering and voting machines — a top priority in their agenda, at all levels of government.

The defeat of Prop 10 -- which would have allowed the expansion of rent control in California -- is bad. The margin by which it was defeated is baffling. Who the hell are all these people who really don’t like rent control? And who are all these people voting to force EMTs to remain on call while they take their breaks? And why does California legislate so many stupid things through ballot initiatives?! At least the greedy boomer home-owners didn’t get their tax break.

There’s more bad stuff. Like that everyone I gave money to lost, except one person, and she’s not even in my state (Jacky Rosen in NV). And my longtime nemesis Diane Feinstein took her race handily. And literal white supremacist Steve King narrowly won back his seat in Iowa.

But there’s plenty of good stuff, too.

More women, and especially more women of color, will now be serving in Congress than ever before. Two of them are Muslim American, two of them are Native American. My home state of Massachusetts elected its first Black woman to Congress (uh, why’d it take so long?), and Boston elected a Black woman as District Attorney.

Medicaid expansion passed in Utah, Idaho, and Nebraska.

Scott Walker lost in Wisconsin (which I assume is due to the presence of @tnelms and @suchasuperlady), and Kris Kobach lost in Kansas (!).

Voter turnout was massive, in comparison with previous midterm elections.

Kim Davis, whom none of us should ever have heard of in the first place, was booted from office.

Massachusetts re-affirmed trans rights.

And lots more.

Here’s the thing. The “blue wave” thing was a media construction that was designed to either work or fail spectacularly — that is, there either would be a wave or there wouldn’t. There’s no in-between, mostly because there’s no room in the metaphor for in-betweenness. Focusing on and thinking through stupid metaphors like this -- and then trying to work within those metaphors, like referring to the “blue trickle” or the “blue particles” (har har) -- distracts us from seeing what has actually happened.

And what actually happened is that the Democrats took a lot of seats in the House, despite what is, according to traditional measures (if not direct experience), a really good economy. One of the only tried-and-true metrics that has held over the decades is that the relative health of the economy dictates whether the incumbent party gains or loses seats in an election. If the economy is doing well, the incumbents tend to hold seats or gain some, but if it’s doing badly, they lose. It’s virtually unheard of for incumbents to lose seats when the economy is doing well, but that’s exactly what happened last night, at least in the House.

And look at those Medicaid expansions in very conservative states. Republicans began the campaign by running on only three issues: healthcare, tax cuts, and racism. They basically gave up talking about the tax cuts they passed, because they were very unpopular, and they ended up outright lying about their position on healthcare since, as it turns out, even in red states, people overwhelmingly want affordable healthcare. So all they’re left with is racism. Now I’m not saying this is a good thing, of course. Obviously not. But it demonstrates that the “issues” that the GOP touts are all smoke and mirrors, and the Democratic positions on those are in fact widely preferred. Plainly, all the GOP has at this point is racism. Once we all understand that, and stop pretending like the GOP is a legitimate, issues-based political party, the better equipped we are to organize around them in the future. Which is to say, anti-racism needs to be a basic building block of everything the left, including the Democratic party, puts forward from now on.

Remember, this is all about power, not just aesthetics or feelings (those matter, too, but only really in relation to power). And the medium and long games are just as important, if not more important, than the short ones. The short game played from 2016-2018 wasn’t perfect, but it was a good step forward because the unfettered power of the GOP now has a few more checks on it. There’s another short game to play starting today, and this one is even more important than the one we just finished. As I’ve said before, I have no love for the Democratic party, but for better or worse, they’re the only force we have right now for stopping a political cult from destroying our fragile democracy, so the best thing to do, from point of view, is help them win this game. I really hope they can do it.

21 notes

·

View notes

Link

(The first paper money issued in Massachusetts, in 1690)

In this episode, we look at how further wars with Quebec combined with the introduction of paper money to create big political divisions in mid-18th century Massachusetts.

>>>Direct audio link<<<

(WordPress) (Twitter) (Libsyn) (Podbean) (YouTube) (iTunes)

Transcript and Sources:

Hello, and welcome to Early and Often: The History of Elections in America. Episode 28: Take My Debts Away.

Over the last two episodes, we talked about the history of New England during the early 1700s, a period which was marked by inconclusive fighting with Quebec. Today, we’re going to talk about the next few decades of New England’s history, with a focus on how Massachusetts actually paid for these very expensive wars.

Massachusetts, and the American colonies in general, had always had problems with a shortage of cash, which made it difficult for the economy to function properly and difficult for the government to collect taxes. Without any money, you have to resort to barter, which is terribly inefficient and seriously hinders the functioning of markets, since it becomes prohibitively expensive to trade with anyone at all. And partly as a result of this shortage, the economy wasn’t actually growing that fast, at least in per capita terms.

They had solved -- or tried to solve -- this problem in various ways. Using crops as a commodity money, like tobacco in the Chesapeake, for instance, using foreign currencies, using the Indian currency of wampum, tolerating piracy in order to get some of that pirate gold. There were attempts to set up private banks that could issue money, but they failed.

Massachusetts had just started minting its own coins in 1652, but it wasn’t clear that they had the right to do so, and the practice was ended when their old charter was annulled. You see, Britain didn’t want to let its colonies mint their own coins. Following the mercantilist economic philosophy of the time, they wanted to hoard gold and silver within the mother country, rather than letting it flow out to the colonies, so they made sure that the movement of gold and silver was one way only. This policy hurt the colonies economically, but since they existed solely to serve British interests, who cared?

So when the wars with Quebec started, Massachusetts needed cash more than ever, but cash was in even shorter supply. So the government hit upon the idea of issuing “bills of credit”. That is, paper money. Paper money had been invented in China many centuries ago, but in the West in the 1600s it was still a novel idea. In fact, when the colony first issued paper money in 1690, the idea still hadn’t even been tried in England yet, though it would be in just a few years. So this was an early experiment, at least within the Western world.

The very first issue of paper money was due to that first failed invasion of Quebec. The government hadn’t made any plans to pay their soldiers, incorrectly assuming that they’d be paid out of the plunder they took. But since the expedition was a complete failure, the government suddenly had to scramble to figure out how to pay the near-mutinous troops. They decided on paper money -- basically an IOU. In order to increase confidence in these dubious-seeming IOUs, the government agreed to give a 5% tax break to anyone who paid their taxes with these bills. It worked, and the currency was accepted.

At first things went well enough, despite some initial doubts. The economy became more efficient and grew as a result. Connecticut also started issuing paper money in 1709, and Rhode Island in 1710. So did many of the other colonies further south.

This system was then expanded and fleshed out over the next three decades.

These days, when the government prints money, every $1 bill is equal in value to every other $1 bill no matter what, but back then it was a little more complicated. Back then, the government issued issued money in batches. So one issue of bills might be printed in 1733, and another in 1735. These bills were then lent to colonists, who would then spend that money and circulate it throughout the economy.

But the important thing is that these different issues of bills could each be redeemed at some point in the future by the government. The money had been given out as a loan, and eventually the government would call in that loan, with different issues of money being redeemed at different times. So really there were a bunch of slightly different currencies going around in the economy, rather than one, and they could sometimes vary in value relative to each other.

And because the government, in printing money, was acting as a lender, it could decide to postpone calling in its debts if it so chose. The government could basically say, “No, no, we’re not going to be collecting that money we issued in 1733 just yet, even though we said we were going to do it now.” This postponement meant that there was more money left in circulation, but it also lowered people’s confidence in the money supply, since they worried that they might not be able to use this money to pay their taxes in the future. Both of these effects meant that if you postponed collecting these bills, the value of the currency would depreciate. So, basically inflation. In effect, this is similar to how the government can cause inflation today, just through a different mechanism.

The ability for the government to inflate the currency meant that monetary policy quickly became a central political issue. If you inflate the value of money, if you make it so that a dollar is worth less than it was before, some groups will win while others will lose.

If you’re a debtor, if you owe someone $1000, then depreciation is good for you. That $1000 is now worth less than it was before, which means that in order to pay it back, you don’t have to give up as much. You effectively owe less money than you used to. If, on the other hand. I’m the creditor who loaned you $1000, then depreciation is bad news. The $1000 I was expecting from you is now worth less than it was before, so now I’m poorer than I expected. There are all sorts of other complications to this, of course, but that’s the essence of the idea.

And inflation, or at least high inflation, could cause problems beyond just making some people more or less wealthy than before. For instance, if you’re a debtor and you expect the currency to be worth less in the future, you might postpone payment of your debts until then. It was cheaper to default on your debt and have your creditor take you to court, since by the time the case was resolved, whatever money you owed would be worth so much less. Therefore, big fluctuations in the value of the currency could wreak havoc on all sorts of economic decisions, as well as clogging up the court system.

So that’s one aspect of monetary policy: how much money to print, and how long to keep it in circulation. But there was another complication on top of that: what should this paper money be backed by? Right now, the money was backed by the loans that had been taken out to get it, and by the fact that you could pay your taxes with the money. Some people wanted to expand this system through the creation of a bank which would issue even more money backed by silver and gold.

Another proposal was to create a land bank. That is, a bank which would offer paper money backed by land rather than by gold or silver. Basically, you as a landowner could take out a loan with the bank, secured against your land. In exchange, the bank would give you money which you could spend, and that money would then circulate through the economy, ultimately backed by the land that had been used to secure those loans. There was a lot of land in Massachusetts, and so a land bank would likely mean a huge expansion in the amount of money in the colony.

There were also disputes about who should run such a bank if it was created. Under some proposals it would be private, while in others, it would be run by the provincial government. If the government was in charge, then it would be easier for the colonists to get more money printed than if the bank were private, since governments are naturally more responsive to public pressure.

I know this might be confusing -- inflation, land banks, silver banks, private banks, public banks -- but the important thing is this: whether or not there’d be more money in circulation overall. If you supported printing a lot more money, then you probably supported creating a land bank. That was the political axis at the time: more paper money vs. less paper money. Everything else is just a particular instance of that bigger struggle.

So, which groups supported printing more money and which ones opposed it? Who supported the silver bank or the land bank, and who opposed both of them?

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to know how or why people voted back then. Even today it can be really, really hard to figure out what it is that voters want from their politicians. You can multiply those problems a hundredfold when it comes to the past. There isn’t that much surviving data, and there were no formal parties, so figuring out which faction a politician belonged to -- if he belonged to one at all -- is often a matter of guesswork and interpretation. And on top of all that, politics was much more local back then, which makes generalizations even harder. Did a politician lose reelection because voters changed their mind on some issue? Because of a personal scandal? Because he didn’t do enough glad handing? Because the economy got worse? Because he neglected to get a local bridge repaired? It’s often simply impossible to say, and so we can only speak vaguely about how the political process actually worked. Outside of some exceptional periods, a lot of change seems to have been due to random local variation, rather than any grand ideas or interests that would seem important to us today.

So the most we can do is look for some general patterns that seem to mostly hold. To that end, we need to turn to a man named Thomas Hutchinson. Hutchinson was both a historian and a politician, who became governor of Massachusetts just before the Revolution. I’ll have more to say about him in a later episode, but for now all you need to know is that before he became governor, Hutchinson had begun working on a multivolume history of the colony, one of the more important sources for modern historians.

Anyway, Hutchinson identified three factions which developed in response to these debates over the currency. These three groups would persist in some form for decades, until the American Revolution itself. Not in any organized way, but still recognizable as the same thing.

The smallest faction (but still sizeable) was the one in favor of ending the experiment with paper money altogether and returning to a system of hard currency. There were always those who saw paper money as a dangerous innovation or some kind of scam, including Hutchinson himself. This faction, centered in Boston and some of the coastal towns, was led by big-time merchants and those who did a lot of business with Britain. They would lose money if inflation were higher. Conservatives like the Mather family were members as well. I’ll call this group the non-expansionists.

Another faction, much larger, favored a private bank which would issue currency. According to Hutchinson, "This party, generally, consisted of persons in difficult or involved circumstances in trade, or such as were possessed of real estates, but had little or no ready money at command, or men of no substance at all". So mostly people with assets who just lacked cash, basically. They wanted to make sure the economy had enough money for them to trade. I’ll call this group the moderates.

The third faction, also quite large, favored a public bank. This faction consisted of somewhat poorer farmers and Bostonians. Not the poorest of the poor, but not the comfortably well off either. Throughout the 1700s about 40% of the delegates from the rural areas came from this faction, which I’ll call the populists.

So the more rural you got, and the less rich you were, the more likely you were to favor loose money, which is not too surprising. It’s always been the case that farmers, whose livelihoods can be wrecked by a single bad harvest, are at great risk of falling into debt. And really, this is part of a very long tradition of farmers wanting debt relief. I mean, you can go all the way back 4000 years ago to ancient Mesopotamia, when kings periodically proclaimed jubilees in which all debts were invalidated, as a way of taking pressure off poor farmers. This was just a financially more sophisticated version of the same thing. And we’ll see similar concerns again in the late 1800s, with many farmers trying to move the United States away from a strict gold standard in order to cause inflation.

Merchants, who were often the guys loaning the money to these farmers, were naturally opposed to such debt relief.

However, although paper money was one of the most important issues faced by Massachusetts, it was by no means the only one. Modern historian Marc Egnal, in his book A Mighty Empire: The Origins of the American Revolution, expands upon Hutchinson’s three factions. According to him, the two larger factions, the moderates and the populists, were both expansionists. That is, they didn’t just want to expand the money supply, they also wanted to expand the European presence in America in general, by growing the economy and moving westwards as fast as possible. They were optimists about America and they were more gung-ho about the wars with France, especially the moderates, since it meant further opportunities for expansion and inflation. When the War of Independence came, they were enthusiastic supporters.

The moderates and the populists had different economic interests, which meant that they didn’t always see eye to eye, but in their view of America’s future they were united.

On the other hand, the smaller faction, the non-expansionists, also tended to be more pessimistic about America’s prospects, at least relative to Europe. Thus, they favored policies which maintained their ties with the mother country, rather than desiring to go their own way. They were more skeptical about the wars with France and they often remained Loyalists to Britain during the Revolution.

That’s just one interpretation, but it seems plausible enough on the whole. Sadly, there doesn’t seem to be all that much research on factionalism in colonial times, at least that I could find, so I’ve had to rely on fewer sources than I’d’ve liked, but hopefully nothing is too far off from the truth.

It might be more accurate to call these groups “interests” or even “dispositions” instead of “factions”, since they aren’t really stable coalitions. Instead, different political alliances will emerge out of these groups, depending on what the important issues of the day are. So the moderates and the non-expansionists might form an alliance for a while, before that disintegrates and the moderates instead ally with some of the populists.

Okay! So that’s the basic dynamic that will be playing out over the next few decades: various proposals to print more money, backed especially by rural farmers, and opposed especially by urban merchants.

However, for the first several decades after the introduction of paper money, inflation remained low and the currency was a minor political issue at best. The financial demands of King William’s War hadn’t been that great and so the government hadn’t had to issue that much paper money. It was only with Queen Anne’s War in the 1700s that monetary policy became an ongoing political concern. The government issued more and more money, which of course meant that the value of that currency kept dropping. In fact, Massachusetts often found itself in the weird position of both having an inflated currency and not having enough money to go around, which only lead to further demands to print money. Connecticut had similar problems as well.

As the war came to a close, a split opened up over what the colony should do. A number of colonists proposed that the government should create a land bank, in order to keep issuing more currency even though the war had ended. The idea for a land bank had been around for a few decades, but this was the first time that it gained serious traction. The current governor, Joseph Dudley, was opposed, while the supporters of the land bank controlled the lower house of the General Court.

Now, in addition to the people of Massachusetts, there were a few other groups which also had a say in whether or not to print more money. Obviously the colony’s government itself had an interest in causing inflation to help pay for the wars. You need more money? Just print more money! What could go wrong?

But the British government, which could veto colonial legislation remember, also had a say, and they opposed inflation. They represented the interests of British merchants, who were creditors and thus stood to lose out should the value of colonial currencies be lowered. So Britain not only opposed minting coins, they also opposed printing bills, even when that hurt the colonial economy. Massachusetts wasn’t represented in Britain and so they got the shaft. Britain could and did use its influence to block growth of the money supply, at least sometimes.

But in any case, thanks to local opposition, the land bank idea was not passed into law. Instead, the government just printed more money and kept older money in circulation. That was enough for now. With the temporary end of the wars, the currency fight died down for a while.

In 1715 Governor Dudley was removed from office and soon replaced by Colonel Samuel Shute, who served from 1716 to 1723. Shute, who had been chosen partly for his opposition to the land bank, was not a native New Englander, and his time in office was very contentious, though not because of the land bank or the currency.

Shute quarrelled with the General Court over appointments and over his salary. (Remember the governors didn’t have a permanent salary and so were at the mercy of the legislature if they wanted to get paid.) He tried to veto the lower house’s nominee for Speaker of the House. The lower house objected to this interference in their affairs and cut Shute’s salary by 200 pounds as punishment. The next year they insisted that Shute approve all their legislation before he be given a salary at all.

Shute left for England in 1723 to complain, but he never wound up returning. In his absence, the lieutenant governor, William Dummer, served as acting governor for most of the next 7 years. Under Dummer there was a small war with some Indians, but things mostly remained calm, and the currency remained a minor issue.

The biggest issue of the day was the so-called explanatory charter. Thanks to the disputes between the governors and the General Court over just how powerful the governor actually was, King George I issued an explanatory charter, which was basically an amendment to the Massachusetts charter which had been issued by William and Mary in 1691. This new document clarified certain provisions in the old charter and enhanced the governor’s powers, though it still didn’t give him a fixed salary.

In order to go into effect, the explanatory charter had to be passed by the General Court. This was a contentious issue. Both the moderates and the non-expansionists favored adopting the explanatory charter, but the populists were opposed. In any case, the charter was in fact adopted, though it didn’t change much, really.

The next governor was Jonathan Belcher, who served from 1730 to 1741. Before his appointment as governor he had been serving as the colony’s representative in London. While in England he apparently managed to convince the officials there that, as a native, he might have better luck in convincing the assembly to give the governor a permanent salary. However, he was no more successful than his predecessors had been.

Over the 1730s, the currency situation gradually worsened, thanks mostly to Governor Belcher.

Belcher had been given specific instructions by the Board of Trade about what to do with the money supply. They wanted him to phase out all paper money over an eleven year period and move Massachusetts back entirely to a gold and silver economy. This was an extremely ambitious policy, to say the least, and it would have led to a huge contraction in the money supply. However, the General Court resisted the plan. The Board of Trade may have been responding to the interests of English creditors, but the legislature was responding to the interests of Massachusetts debtors.

As a result of this standoff, much less money was issued for a few years. Instead, the bills that were already in circulation were kept in circulation for longer, which led to further economic problems.

Governor Belcher was in a difficult position. When he came to an agreement with the General Court to print more money, the Board of Trade threatened to remove him from office. They still wanted Belcher to get rid of paper money altogether. There simply seemed to be no position which would satisfy both the legislature and the Board of Trade.

He tried to come up with a compromise position, issuing a new government currency backed by silver and gold, while taking the old currency out of circulation. However, people just hoarded the new currency, since it was seen as more valuable, even as the old currency was being eliminated. Thus Massachusetts was left without much cash at all. (In economics, that’s known as Gresham’s law: bad money drives out good. If people have two currencies to choose from, they’ll all hoard the more valuable one and it may disappear from circulation altogether.)

As the money supply once again became an important issue, Massachusetts once again became divided over whether to create a bank to issue more currency. The populists supported the creation of a land bank, while the other two factions supported the creation of a bank which would be backed by silver.

However, neither proposal got enough support in the General Court to pass, and presumably the governor would’ve had to veto them anyway. So instead of a public bank run by the government, some of the colonists decided to form a private bank instead. Both a private land bank and a private silver bank were created. The silver bank was supported by merchants, who opposed the land bank. However, the land bank proved widely popular among everyone else. It soon had almost a thousand subscribers and its currency went into circulation. Even a few moderates decided to participate in the land bank.

However, the Board of Trade continued to oppose any measures which would lead to currency depreciation, even if it wasn’t being done by the government itself. So they put pressure on Governor Belcher to quash these banks, and he did what he could to stop them, by forbidding all lawyers and government employees from doing business with the land bank and firing all those who did.

That wasn’t enough to stop the land bank’s growth however, and in the elections of 1741, supporters of the land bank became a majority in the General Court, as well as winning many local elections. But whatever the people thought about it, they didn’t have the final say. Back in London, Parliament passed legislation which essentially banned the land bank. A firm reminder of who really controlled Massachusetts these days. And so the colony’s money supply continued to see-saw back and forth haphazardly. Not good for business.

Around this time, Belcher fell from power and was removed from office, although not really because of the currency dispute. Instead, it was because his patrons back in England had themselves fallen from power, so that when his enemies mobilized against him, there was no one in London to look after his interests. Again, politics in Massachusetts had become a function of petty disputes within the British government.

Belcher’s replacement was William Shirley, who would serve as governor for most of the next 15 years, during the entirety of King George’s War, and the beginning of the French and Indian War.

Shirley had been born in England, but he went to Massachusetts in 1731, not out of any Puritan conviction -- which would have been an anachronism at this point -- but as an ambitious lawyer looking to make his way in society. Upon arrival he soon joined the faction opposed to Governor Belcher, and after Belcher was removed managed to get himself appointed to the job, thanks to his connections back in England, which I guess proved superior to Belcher’s connections.

Shirley did his best to be cooperative with the General Court. He brought up the issue of a permanent salary, but only briefly and only once, just to get it out of the way.

He was conciliatory towards the populists and he managed to get some of them on his side, but as far as the land bank goes his hands were tied by Parliament. He had no choice but impose regulations on the land bank which caused it to swiftly collapse, which of course only led to further economic woes. For example, Samuel Adams, Sr., father of the famous revolutionary Samuel Adams, lost most of his wealth.

It was not a popular move. John Adams, the future president, who was a child at the time, said that the attack on the land bank was even more hated by the colonists than the hated Stamp Act would be.

Things seemed to be going from bad to worse, but before the economy could totally collapse or anything, something happened which interrupted all of these problems: another war with France.

So now it’s time to jump back to English politics, and catch up with the last few decades of events.

When we last left England, the War of the Spanish Succession had come to an end and Queen Anne had just died. Because she had no surviving children and because Catholics were now legally barred from becoming king or queen, the throne now passed to her second cousin, George I, of the House of Hanover. The Hanovers were a moderately important German dynasty, who, up until now, had basically nothing to do with Britain.

As a foreigner who didn’t speak the language that well and spent a lot of time in his native country, King George was naturally less involved in British politics than his predecessors had been, further strengthening Parliament’s control.

Anne had favored the conservative Tory party, but George was concerned by their connection to the Jacobites, the supporters of the Stuart dynasty’s claim to the throne and opponents of the Glorious Revolution. There weren’t that many Jacobites left, but they were still seen as a threat to King George’s legitimacy. So instead he favored the Whigs, who entered a period of political dominance which would last decades.

Under William and Anne, elections to Parliament had been held every three years, which led to a hothouse political atmosphere, where both the Whigs and the Tories fought it out in the press day after day. But in 1716 Parliament passed the Septennial Act, which meant that now elections only had to be held every seven years. This was partly just a power grab by the Whigs, designed to keep themselves in office longer, but it did have the effect of calming things down considerably.

It also helped that Europe was entering a period of relative peace. Louis XIV had died in 1715, after 72 years on the throne, so French ambitions were reduced for the time being. England and France even wound up as allies for a while.

The most important political development under George I was the creation of the office of prime minister. Previously, there had never been a single person in charge of government other than the king himself. Well, now there was, at least unofficially. That man was Robert Walpole. Walpole was a Whig who had joined Parliament in 1701 and gradually risen to prominence. Thanks in part to his deft handling of a financial crisis known as the South Sea Bubble, by 1721 he had become the leading figure in the cabinet, a position he held for the next two decades. There had been leaders in the cabinet before, but this was unprecedented.

This was a new way of doing things, a new center of power in which a member of Parliament was placed in charge of the government, permanently dependant on Parliamentary support to get anything done.

Walpole was very skillful at handling Parliament, he was cautious in his ambitions, and he had good luck in general, allowing him to stay in power for so long. The Tory party receded into near-irrelevance. The political scene was as calm as it had been for the better part of a century.

George I died in 1727 and was succeeded by his son George II. Nothing much changed. The new king continued his father’s policies and even kept Robert Walpole on as prime minister. Walpole continued his grip on power and Britain continued its headlong transformation into a commercial empire. Peace was maintained thanks to the temporary alliance with France.

Walpole’s rule was controversial, and he was subject to constant attacks in the press. Often he was accused of corruption. He was corrupt, though probably not more so than his predecessors. He just had such power that most of the corruption and patronage in the realm flowed through his hands, which made him a very obvious target. But despite the constant antagonism, Walpole’s skills were such that he managed to survive each crisis as it came up, keeping both Parliament and King on his side each time.

But they say that all political careers end in failure, and Walpole was no exception. After 30 years of relative peace, war returned. At first the conflict was small, just a trade dispute with Spain known as the War of Jenkins’ Ear. The impact on the American colonies was minimal.

However, the struggle went badly for Britain and Walpole took the blame. In the elections of 1741 he nearly lost his majority and it was clear that his support was continuing to erode. Soon, he would no longer be able to control Parliament. The writing was on the wall and so Walpole resigned. There were some attempts to prosecute him for corruption, but they came to nothing.

His two decades as Prime Minister had set a whole bunch of new precedents for British politics, not unlike the presidency of George Washington in America. A new form of government was being worked out on a practical level.

Anyway, I’m mentioning all this stuff about English politics partly just to point out that nothing similar was happening in America. There were powerful politicians in the colonies, of course, but none who could be called a prime minister, no one who relied on the support of the legislature in the same way. And neither were the same political factions present in America. By the time of the Glorious Revolution, the colonies and the mother country were set firmly on different political trajectories, even though they remained attached for the better part of a century afterwards.

Anyway, although Walpole was gone, the war continued. Actually, a much bigger war was brewing in Europe, one that would swallow up the war with Spain. This bigger war, the War of the Austrian Succession, was, as you probably guessed, fought over the question of who should rule Austria. The main claimant for the throne, the one backed by Britain, was Maria Theresa, mother of Marie Antoinette. France, however, hoping to weaken Austria, backed a different candidate. And so a new war was on, for the future of Central Europe. Once again Britain and France were at war.

But the colonists didn’t care about Central Europe. All that mattered to them was that they were at war with Quebec again. In America, the conflict was known as King George’s War, a name which made perfect sense at the time, but is a bit confusing these days given that there were three more King Georges in a row after the first one.

Anyway, because of the war, the Board of Trade reversed its opposition to paper money for the time being, since they needed Massachusetts to have a functioning economy in order to fight the French. The land bank was still dead, but the government was printing a whole lot more money, so the problems of the last decade temporarily vanished.

This had the effect of scrambling the alliances between the populists, moderates, and non-expansionists. Instead of paper money, they were now fighting over the war effort. Governor Shirley was taking aggressive action against Quebec, with the support of the moderates and many populists, while the non-expansionists and some populists opposed him.

Things had really changed since the Glorious Revolution. Now, New Englanders could be downright patriotic about their place in the British empire, at least when the British weren’t annoying them with bad policy decisions. So many Americans took to the war with gusto.

The English had captured the French fort at Port Royal in the last war, but the French had since built an even stronger fort, Louisbourg, a few hundred miles further up the coast. It had 250 cannons and walls 30 feet high. From this fort they could disrupt English shipping and fishing in the region. But the English had intelligence that the fort was undermanned and so Governor Shirley decided to launch an attack, with the assistance of the British and the other colonies.

Astonishingly, considering the colonists’ track record, the attack was a success. The force they sent struggled for the first month of the siege, but then they managed to capture an incoming French warship carrying supplies and weapons for the fort. The French surrendered soon after that.

France tried to send a force to retake Louisbourg, but in a surprising reversal of how things normally went, the French expedition turned out to be a disaster. The French didn’t even manage to reach their destination.

Other than the siege of Louisbourg, the war was mostly just normal raiding back and forth, as well as some privateering at sea. Thankfully, it was a brief war, lasting only 4 years, at least in the colonies.

Once again, I don’t think there’s any need to get into how the war went in Europe. The British-backed Maria Theresa became Empress of Austria, but it was just as inconclusive as the wars of the last generation. However, in the final peace treaty, the fort of Louisbourg was returned to the French, which must have severely stung the pride of the New Englanders.

But probably the most important impact of the war in Massachusetts was that the colony now had massive debt and a currency which was worth only like a tenth of what it had been worth a few decades ago. It’s not the worst example of hyperinflation in world history, but it wasn’t exactly a great track record either.

Governor Shirley, who had been the one inflating the currency to fund the war effort, now reversed course and tried to pull things back. This also meant a change in his allies. He shifted away from the populists and towards the non-expansionists. In fact, he shifted hard in the other direction.

The British government had agreed to reimburse Massachusetts for some of its war expenses, and it was proposed to use that money to buy back all the paper currency left in circulation and return Massachusetts to a hard money standard of just silver and gold.

Paper money was still popular with many of the colonists, but thanks to all of the problems that there had been, the plan won enough support to pass. And so in 1750 Massachusetts ended its experiment with paper money. Not only that, in 1751 the British Parliament passed an act which prohibited the colonies from printing any paper money that wasn’t backed up by gold or silver.

Now, that didn’t mean that the colonists had come up with another solution to replace paper money. Far from it. The switch back to silver and gold meant that once again there wasn’t nearly enough currency to go around and the economy suffered as a result. But for the time being, thanks mostly to British pressure, there was nothing to be done about it. Paper was dead.

It’s safe to say that this first experiment with paper currency was a failure, at least in Massachusetts. Though in some other colonies it went better. What accounts for this failure?

Well, firstly I think that Massachusetts was torn between two forces: popular support for inflation and British opposition to inflation. The back and forth between those two sides meant that the amount of money in circulation kept fluctuating, and the colonists faced an always uncertain economic future. How much would your money be worth in a year? How could you know? And in general, it’s going to be hard to have a paper currency if you’re a colony and your home government is against the idea. Massachusetts simply had limited sovereignty.

Secondly, the monetary system was much too open to popular pressure. These days, America’s monetary system is controlled by unelected officials at the Federal Reserve, while in Massachusetts the decision to print money was made by elected officials. Back then elected officials weren’t as responsive to public opinion as they are today, but officials certainly were aware of what their constituents wanted, and they acted accordingly.

And thirdly, paper money was a novel experiment and no one really knew what they were doing yet.

Taken together, all of this lead to a very unstable system, with periods of rapid expansion of the monetary supply matched by correspondingly rapid contractions, neither of which were good for the economy as a whole. Sometimes there was so little money in circulation that New Englanders had to resort to barter. Arguably, paper money was still better than having no currency at all, but it definitely didn’t work as intended.

Better luck next time.

Next episode, we’ll look at the history of Rhode Island during this period, and how a regional rivalry there led to a different sort of factionalism. So join me next time on Early and Often: The History of Elections in America.

If you like the podcast, please rate it on iTunes. You can also keep track of Early and Often on Twitter, at earlyoftenpod, or read transcripts of every episode at the blog, at earlyandoftenpodcast.wordpress.com. Thanks for listening.

Sources:

Revolutionary New England, 1691-1776 by James Truslow Adams

The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Volume 3 by Thomas Williams Bicknell

Currency and Banking in the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay, Part II: Banking by Andrew McFarland Davis

A Mighty Empire: The Origins of the American Revolution by Marc Egnal

Thomas Hutchinson and the Province Currency by Malcolm Freiberg

A Land of Liberty?: England, 1689–1727 by Julian Hoppit

The History of the Province of Massachusetts-Bay: From the Charter of King William and Queen Mary in 1691, Until the Year 1750 by Thomas Hutchinson

Colonial Rhode Island -- A History by Sydney V. James

Adjustment to Empire: The New England Colonies 1675-1715 by Richard R. Johnson

Colonial Massachusetts -- A History by Benjamin W. Labaree

A Polite and Commercial People: England 1727-1783 by Paul Langford

The American Colonies in the Eighteenth Century, Volume I by Herbert L. Osgood

The American Colonies in the Eighteenth Century, Volume II by Herbert L. Osgood

History of New England, Volume IV by John Gorham Palfrey

Currency Policies and Legal Development in Colonial New England by Claire Priest

Old Lights and New Money: A Note on Religion, Economics, and the Social Order in 1740 Boston by Rosalind Remer

Succession Politics in Massachusetts, 1730-1741 by John A. Schutz

Colonial Connecticut -- A History by Robert J. Taylor

The Land-Bank System in the American Colonies by Theodore Thayer

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Are The Chances Of The Republicans Winning The House

New Post has been published on https://www.patriotsnet.com/what-are-the-chances-of-the-republicans-winning-the-house/

What Are The Chances Of The Republicans Winning The House

Opinionhow Can Democrats Fight The Gop Power Grab On Congressional Seats You Won’t Like It

WATCH: Democrats ‘have a good chance of winning the White House, Sen. Lindsey Graham

Facing mounting pressure from within the party, Senate Democrats finally hinted Tuesday that an emboldened Schumer may bring the For the People Act back for a second attempt at passage. But with no hope of GOP support for any voting or redistricting reforms and Republicans Senate numbers strong enough to require any vote to cross the 60-vote filibuster threshold, Schumers effort will almost certainly fail.

Senate Democrats are running out of time to protect Americas blue cities, and the cost of inaction could be a permanent Democratic minority in the House. Without resorting to nuclear filibuster reform tactics, Biden, Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi may be presiding over a devastating loss of Democrats most reliable electoral fortresses.

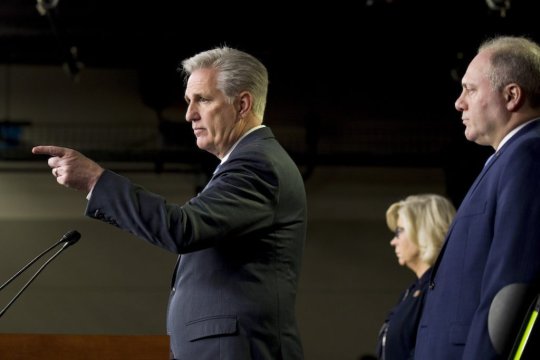

Mcconnell: House Senate Gop Wins In 2022 Would Check Biden

Addison Mitchell McConnellHouse approves John Lewis voting rights measureThe Hill’s 12:30 Report – Presented by AT&T – Pelosi’s negotiates with centrists to keep Biden’s agenda afloatMcConnell urges Biden to ignore Aug. 31 Afghanistan deadlineMORE on Thursday pledged that if Republicans win back control of Congress next year they could be a check against the Biden administration, forcing it into the political center.

McConnell, speaking at an event in Kentucky, said that American voters have a “big decision” to make in 2022, when control of both the House and Senate are up for grabs.

“Do they really want a moderate administration or not? If the House and Senate were to return to Republican hands that doesn’t mean nothing happens,” McConnell said.

“What I want you to know is if I become the majority leader again it’s not for stopping everything. It’s for stopping the worst. It’s for stopping things that fundamentally push the country into a direction that at least my party feels is not a good idea for the country,” he added. “And I could make sure Biden makes his promise … to be a moderate.”

Democrats are trying to keep their majorities in both the House, where they have a nine-seat advantage, and the Senate, which is evenly split but where they have the majority since Vice President Harris is able to break ties.

The Cook Political Report rates both the Pennsylvania and North Carolina seats as toss-ups, and Johnson’s seat as “lean R.”

What To Know About The Gops Chances Of Regaining The House

This month, the National Republican Congressional Committee ran a poll regarding the most competitive seats up for grabs during next years congressional midterms. The findings were quite telling and spell bad news for Democrats maintaining their current and slim majority.

For starters, in districts categorized as Trump/Democratic, the unfavorable rating of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi hits a whopping 60%. This comes on top of the revelation that 57% of U.S. voters believe that Bidens stimulus aid is failing to provide the necessary relief for themselves and their relatives.

With the American Jobs Plan, were going to bring quality, affordable high-speed internet to every single American no matter where they live.

President Biden

In regards to the U.S. economy and jobs in America, 46% of polled Americans stated that they favor Republicans more than Democrats. Just 41% claimed that they have more faith in Democrats than Republicans when it comes to U.S. jobs and the economy.

Finally, three-quarters of Americans described the ongoing Southern border crisis as a significant problem in the nation.

Don’t Miss: Which Region In General Supported The Democratic Republicans

Will Republicans Take The House In 2022

The odds that the Republicans will take the House of Representatives in 2022 are currently unknown, and sportsbooks haven’t posted lines to this effect just yet. As the races near, of course, the top Vegas election betting sites will have odds for every contested seat in the US House.

When betting, it’s important to weight various factors that will affect the GOP’s ability to win a majority in the House, such as the party affiliation of the sitting President, the laws that have been passed recently, and any scandals that might tarnish either side. The Republican party won all 27 US House seats graded as “toss-ups” in 2020, chipping away at the Democratic House majority, and should that trend continue, the GOP could easily flip the lower chamber.

Possible 2010 Or 2014 Midterm Repeat

Big bets on policy also don’t necessarily pay off at the ballot box, a lesson Democrats learned a decade ago when they passed the Affordable Care Act. President Barack Obama’s domestic policy achievement also helped decimate congressional Democratic majorities in the 2010 and 2014 midterm elections.

It’s just one reason why Republicans feel good about their chances in 2022, along with structural advantages like the redistricting process, where House districts are redrawn every decade to reflect population changes. Republicans control the process in more states and are better positioned to gain seats.

“This deck is already stacked, because they’ve been gerrymandering these districts,” Maloney says. “And now they’re trying to do even more of it and add to that with these Jim Crow-style voter suppression laws throughout the country.”

He maintains that efforts among Republican-led state legislatures to enact more voting restrictions show the party has a losing policy hand for the midterm elections.

You May Like: Why Do Republicans Wear Blue Ties

National View: Republican Resurgence In 2022 Already On The Horizon

Reading the political tea leaves 18 months in advance is as tricky as making a weather forecast for the same timeframe. But every so often, circumstances combine to increase the odds in the forecasters favor. Looking ahead to next years midterms is one of them. Because if things continue on their current course, Nov. 8, 2022, will be a very good night for Republicans around the country.

For starters, history is on the GOPs side going into the campaign. Theres a long track record of the incumbent presidents party losing seats during a midterm election. In fact, since 1934, only two presidents have enjoyed an increase in their partys numbers in the House and Senate: Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934 and George W. Bush in 2002.

Excluding those two exceptions, losses are big for the party that occupies 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Especially for first-term presidents and particularly in the House. Consider Presidents Donald Trump , Barack Obama , Bill Clinton , Ronald Reagan , and Gerald Ford . All were shellacked at the ballot box, resulting in significantly fewer members of their party in the House of Representatives.

According to FiveThirtyEight, the GOP also has a turnout advantage in midterms. Under Republican presidents since 1978, the GOP has enjoyed a plus-one shift toward party identification for those who vote in midterm elections. That margin swells to plus-five under Democratic presidents.

Opinion: The House Looks Like A Gop Lock In 2022 But The Senate Will Be Much Harder

Redistricting will take place in almost every congressional district in the next 18 months. The party of first-term presidents usually loses seats in midterms following their inauguration President Barack Obamas Democrats lost 63 seats in 2010 and President Donald Trumps Republicans lost 40 in 2018 but the redistricting process throws a wrench into the gears of prediction models.

President George W. Bush saw his party add nine seats in the House in 2002. Many think this was a consequence of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on America nearly 14 months earlier, but the GOP, through Republican-led state legislatures, controlled most of the redistricting in the two years before the vote, and thus gerrymandering provided a political benefit. Republicans will also have a firm grip on redistricting ahead of the 2022 midterms.

The Brennan Center has found that the GOP will enjoy complete control of drawing new boundaries for 181 congressional districts, compared with a maximum of 74 for Democrats, though the final numbers could fluctuate once the pandemic-delayed census is completed. Gerrymandering for political advantage has its critics, but both parties engage in it whenever they get the opportunity. In 2022, Republicans just have much better prospects. Democrats will draw districts in Illinois and Massachusetts to protect Democrats, while in Republican-controlled states such as Florida, Ohio and Texas, the GOP will bring the redistricting hammer down on Democrats.

Don’t Miss: How Many Republicans Voted For Impeachment

House Passes $35t Budget Framework After 10 Dem Moderates Cave To Pelosi

The House Democrat in charge of making;sure the party retains control of the chamber after next years midterm elections is warning that a course correction is needed or they could find themselves the minority again with current polling showing the Democrats would lose the majority if elections were held now.

Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney, the chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, told a closed-door lunch last week that if the midterms were held now, Republicans would win control of the House, Politico reported Tuesday.

Maloney advised the gathering that Democrats have to embrace and promote President Bidens agenda because it registers with swing voters.

We are not afraid of this data Were not trying to hide this, Tim Persico, executive director of the Maloney-chaired DCC,;told Politico;in an interview.

If use it, were going to hold the House. Thats what this data tells us, but we gotta get in action,;Persico said.

Maloney, in an interview with NPR, said issues like climate change, infrastructure, the expanded child tax credits, immigration policies and election reforms will;attract voters next fall.

Were making a bet on substance, Maloney said. Whats the old saying any jackass can kick down a barn, it takes a carpenter to build one. Its harder to build it than to kick it down. And so were the party thats going to build the future.

Maloneys dire warning failed to surprise some Democrats who have been sounding similar alarms.;

House And Senate Odds: Final Thoughts

Democrats have ‘good chance’ to win White House: Senior Republican

There is less than 1% equity on the notion that Democrats will win the House and lose the Senate, because while New Hampshire could move in a weird, contradictory manner, if Democrats win the House, the nation will be sufficiently blue that they hold all three of Nevada, Arizona, and Georgia, and they will gain Pennsylvania too.

Races are too nationalized and partisanship too entrenched for the Senate GOP to outrun a national environment blue enough to win the House, which means you can get a Democratic Congress for another term at $0.21. Its a better value than the House outright market for almost no extra risk, and thats the best kind of value.

Don’t Miss: What Are The Main Differences Between Democrats And Republicans

Big Odds For Republicans To Win Back The House Of Representatives Next Year

The internal consultation of the National Republican Congressional Committee revealed that their party has favorable conditions to retake the majority of seats in the House of Representatives in the mid-term elections to be held next year.;

Contributing to these good predictions is that voters prefer Republicans as their leaders, and the increased unfavorability of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, according to data provided by the NRCC website on April 26.;

Even the decennial census results are on the side of a Republican triumph because the data presented by the Census Bureau show that they gained seats in the new distribution, although it is not definitive.;

Likewise, throughout the 100 days of the Biden administration at the helm of the White House, Americans have become alerted to the convenience of changing the political course.;

In this regard, NRCC spokesman Mike Berg commented in a statement, The Democrats dangerous socialist agenda is providing the perfect roadmap for Republicans to regain the majority.

Among voters most pressing considerations are the border crisis and the rampant illegal immigration that the Biden and the Democrat open border policies have fostered.;

At least 75% of voters see the border situation as a crisis or significant problem, while 23% say the border is a minor problem or not a problem at all.

Thus, 57% of voters do not believe that the CCP Virus stimulus approved by Biden is helping them and their families.