#I think children being born in places like Gaza is different because it's the survival of an oppressed people even in the terrible situation

Text

as someone born into a bad situation with someone who had things wrong with them personally & genetically that they passed onto me! I cannot say I am against fully voluntary eugenics for both myself and others

#buzgie ❁#theres literally no ethical way to force it on people but if you have something significantly wrong with you that you will pass on#you should not reproduce#I'm anti natalist in general which a lot of people seem to have some issue with#I think children being born in places like Gaza is different because it's the survival of an oppressed people even in the terrible situation#so I cant exactly judge#but I am a hispanic cracker living in the US of A my mom had a one night stand and had the wrong guy in the delivery room#I wasn't vaccinated until I was 8#I have autism and severe social anxiety to the point where I am a NEET that can't participate in society like a normal person#all because my mom didnt use a condom when she had sex one night! and yes I *will* judge her for that!#I know the specifics of my situation enough to say that I think my mom does not value human life the way she produced me#and I think carelessly having an entire human being in the internet age is disgusting. there is literally no way you can't know this shit#where do babies and STDs come from. quick.

0 notes

Text

The images and videos coming out of Rafah are horrific. Now is not the time for "no words" but I have never in my life seen such destruction and genocidal intent openly displayed while our governments try to convince us that the perpetrators are defending themselves. I was an infant when the Iraq War started, so I never saw the media manipulation or the Bush administration’s tactics firsthand. Studying the Vietnam War under Johnson and Nixon is…I don’t know….it feels different. Everything feels different. It feels like people actually cared, but not for the benefit of the Vietnamese people (many anti-war advocates were, though, I should not discredit them), they cared because they didn’t want to be drafted or they wanted the soldiers home. Those are perfectly valid reasons to protest a war, yes, but Vietnam was the first time we truly saw the civilian impact broadcasted on television. People were completely and utterly horrified, much like they are now. However, the media companies who published such horrific images out of Vietnam are now spreading Israeli propaganda and lying about the civilian impact. Just the other day the Atlantic was justifying the murder of children if they were being used as human shields. It is not alright when innocent children are killed, of course, but why is the murder of "guilty" children justified? Who wields the power to determine if the child is guilty?

Of course, we know that none of the children burnt alive or beheaded in Rafah last night were guilty of any crime other than being born Palestinian in Gaza. This crime was deemed worthy of execution by the terrorist Israeli army. The United States manufactures the bombs that kill them, most European nations turn a blind eye or continue to fund this "army”, the countries that pretend to care are performative at best. Surrounding Arab nations will take in refugees, the existing camps will have to survive with even less resources because UNRWA is underfunded (and probably won’t be renewed in 2026) - and, once again, the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who were lucky enough to escape being burnt alive, flattened by bulldozers, or left to rot in the rubble of bombed shelters are displaced once again, as Gaza’s population was made up of ~80% of people who were displaced from other parts of Palestine.

Fuck Israel. Fuck the complicit Arab nations. Fuck complicit European countries and politicians. Fuck the corporations profiting off of this or supporting Israel’s terrorist army. And, most importantly, fuck the United States and the Biden administration for their continued, unrelenting support.

May the souls of the dozens of Palestinian lives lost last night rest in peace. I keep thinking, of course, about the video of the beheaded child that has been circulating around. I want to get that image out of my head because that child deserved to be remembered for much more than just their corpse. I cry every time I see the artwork of the children crushed by the rubble when Rafah was under siege a few weeks ago. They deserve to be remembered for anything else but their dead bodies.

I’m sorry that this is coming from an Animal Crossing blog of all places. I just have a lot of anger and expressing it through writing like this helps. I keep a private journal with much more explicit, uncensored thoughts, but I want to make my position absolutely clear. No amount of Palestinian violence will ever justify Israel’s response, which is ALWAYS destruction, murder, and ethnic cleansing.

If you demand sources, I have them, and I’m not a pussy. I’ll send you my published papers and articles.

0 notes

Text

If the borders refuse me, I refuse them

(You can read a Swedish translation of this text here.)

I mentioned this project to a friend. She immediately said: You should talk to Ghayath Almadhoun.

Ghayath Almadhoun is a poet whose poetry has touched me. He is also a poet working with several languages, living and writing in many places. Finding a time when we could meet was a challenge, due to his frequent travelling. I’m happy we managed. His account of travelling for work brings together the personal and the political, the funny and the sad, the historical and the present, in extraordinary ways.

Ghayath Almadhoun:

I travel for many reasons that I hardly understand. Some of them started already in childhood. I was born in Damascus, with a Palestinian father and a Syrian mother, in the Yarmouk refugee camp for Palestinians. It was just tents when they founded it in 1948, but now it has become buildings, part of the city. The first questions in my life were: What are we? Why do they say that we are not Syrian but Palestinian? Why, then, am I not in Palestine?

It was very difficult for my father to explain to a six-year-old why land in Asia provided a solution for the antisemitism and racism against the Jews in Europe. But later, things became even more complicated. I discovered that I am not Palestinian-Syrian. I am a Palestinian from Syria. The Palestinian-Syrians are the Palestinians who arrived to Syria in 1948, when Israel occupied eighty per cent of Palestine. As the United States, the Soviet Union and Europe all accepted this, the Arabic governments understood that the land that was occupied had become Israel. As a solution, they gave the refugees all the papers they needed. So those who arrived from Palestine to Syria in 1948 have the same civil rights as the Syrian people.

But our family came after the occupation of Gaza, in 1967. When Israel occupied the Gaza strip, the West Bank, the Golan Heights from Syria, Sinai from Egypt and some parts of Jordan, the international community said: “This is occupation, and Israel should leave.” The Arabic nations then decided to not give any papers to these Palestinians in order to not provide any solutions for Israel.

I found myself growing up without civil rights. I was not allowed to work. I was not allowed to take driving lessons. I was not allowed to leave the country, and if I did leave for any reason, I would not be allowed back. As we were not allowed to own a house, the house is in the name of my mother, who is Syrian. But if she died, the government would take the house and sell it. This, that I couldn’t inherit, was the thing that hurt me the most.

When I understood that I was already born outside, in exile, as they say, I became fascinated by the idea that there are no borders. If the borders refuse me, I refuse them. When I began to study, I also understood that my father was a poet. I began to think about poetry. I felt connected to many Surahs in the Quran, such as The Poet’s Surah, Surah 26. At the end of the Surah, it says:

“And the poets – the deviators follow them;

Do you not see that in every valley they roam

And that they say what they do not do?”

Travelling is the reality of Arab poets, and poetry is very much connected to travelling in the Arabic tradition. Take the most famous Arabic poet El Mutanabbi. In the 800th century, he travelled, but most of all, his poetry travelled. If El Mutanabbi said a poem in Bagdad, the people in Damascus got it in a matter of hours by pigeon. From there, it went everywhere. His poem would arrive in Andalusia within a week. He himself came two months later.

So, I began to write poetry. My friends all went to Beirut, to Jordan or anywhere. They got invitations to go and read there. But I couldn’t travel, because I didn’t have a passport, papers or even an ID. So, the pressure began to build inside. This continued until I turned thirty, in 2008. Then I left the country. I made a sort of fake passport and went to Sweden. After I got a real Swedish passport, it’s: “Catch me if you can!”

The travelling is also connected to my writing. For example, I could visit a place, read about it, discuss it and then I write a poem. I did it for example when Assad used chemical weapons on the suburbs of Damascus. Many people got killed in the first attack with the nerve gas sarin. There were 1,400 deaths, out of which 900 were women and children. I saw these bodies shaking. The pupils of the eyes go small. I started to think about chemicals. And I found that the first chemical attack happened in the city of Ypres in Belgium, on 22 April,1915. I went there for the 100th anniversary of that event. I visited 170 cemeteries. They counted 600,000 graves, and I visited all of them in two weeks. At one gate, they have written the names of all the dead soldiers no matter where they came from – France, England, Canada. They play music in honour of one of them every day and speak about what they know about that specific soldier. They had done this for eighty years without stopping for one single day. Even during the Second World War, they played every day. The problem is that they need 600,000 days to finish the names. I listened to such concerts for fourteen days. Then I wrote a poem that moves between the past and the present, Ypres, Syria and Palestine.

Another time, I went to Antwerp to do research about blood diamonds. But during that month, thousands of people started to drown in the Mediterranean. So, my poem started with blood diamonds and ended with Syrians drowning in the sea. By the way, this is not political poetry, this is my life.

So, all in all: I travel in order to write. I’m making up for what I missed when I was without papers. I’m a travelling poet like in the Quran. And I’m born in no country, so I don’t believe in borders. But the main reason why I’m travelling like I have been doing now, 345 days a year and not even staying in Sweden for a full week, is another.

When I came to Sweden, I accepted Stockholm as my city because Damascus was in the background. Every time I felt tired of being a foreigner, I remembered that Damascus was there, that one day I could go back and feel relief. In 2011, the Syrian revolution began. I really supported it, and it made my hopes of going to Damascus grow. But people I knew got killed, family members, almost all my friends. Cities I knew were destroyed. And the dictatorship won. The country was destroyed. My hopes of ever going back were lower than ever. Damascus disappeared from my background. Everything was shaken. Also, Stockholm didn’t belong to me anymore.

What broke me was my brother. I lost him on 2 April 2016, killed by Assad. I was on tour: I was supposed to spend fifteen days in Holland. The second gig was with Anne Vegter, the poet of the nation. We finished our discussion. I went outside and I put the mobile on. Then my other brother called and told me. I disappeared from the universe for two hours. I woke up with people around me. We went to our friend’s house and I asked him to book me a ticket to Stockholm. The coming twenty-four hours were the most difficult in my life. While the plane was over Denmark, I understood there was something wrong. I wanted to tell the pilot to stop and let me off. Why was I going to Stockholm and not Damascus? Stockholm is even further away from Damascus. What is the difference if I cry in Amsterdam or if I cry in Stockholm?

So I started travelling this way. As I see it, the best way to survive trauma is to be on the road. When you arrive, the problems will come. I noticed this in someone I know who was in Syria for four years during the bombings. He lost all his friends. People died in his arms. ISIS arrested him before he left the country. His trip here took eight months. All that time, he was doing ok. But when he got here, it took forty days and then the post trauma hit him. That made me even more scared. So, I began to ask myself: What will happen if I begin to travel and never let myself arrive? The panic attacks will wait for me to be settled. But what if I don’t settle?

After the death of my brother I wrote a poem. The writing took place in maybe sixty places, twenty countries. If I would sign it with the names of the cities, that would be as long as the poem.

What held me in this is that somebody else paid most of my tickets and travels. In this sense, I survived through poetry twice. On one hand, it’s about writing for survival; writing what hurts me on a paper. But then there are the festivals and the residences and the scholarships bringing me from here to there. Many of these festivals were shocked that I only needed one ticket. Germany pays my ticket from France. Belgium pays my ticket from Germany. Everyone pays only to bring me.

It happens that there are holes in the schedule, maybe even seven days empty. I fill these holes in order to not stay. I ask the festival to make my ticket longer and I pay the hotel myself before I go to the next festival. Or, if the ticket can’t be changed, I book a flight to the Arabic book fairs. In Arabic countries, the book fairs are two to three weeks long. And they schedule them in a systematic way, so they cover the whole year. Any time you want to go to a book fair in an Arabic country, you can. There are around 540 million Arabic-speaking people in the world, in 22 countries with 22 totally different cultures. So, when you go there to sign your book, there will be completely different receptions. You’re a star in Kuwait, they hate you in Libya, and you’re a bestseller in Iraq…

I don’t even remember all the places I have been to, I mix them up. The security personnel in the airport know me and say hello to me. Sometimes I see them in the morning. I go home to throw out the summer clothes and throw in the winter clothes because I’m going to the other side of the planet. Then I see them again in the afternoon.

People understand after a while that if they are trying to stop me, they will lose me. If the train is fast and heavy, you should go with it, not stand in front of it. But the routine with friends is you go to their house, bring wine and cook and they come to you next time. When you are travelling again and again and don't have dinner with them, they are not your friends anymore, in a way. You lose your roots.

It is so good when you arrive in places like sunny California, cornfields and wine. And meeting people, discussing with them, having good food, having intellectual exchanges about philosophy, life, racism, patriarchy, everything I’m interested in. But physically it’s tiring. I have a theory I call The Pillow Theory. There are problems in life such as patriarchy, occupation, capitalism and the differences in the shape of pillows in the hotels. I’m fighting for the right of every person to have a size that fits them.

Because of pillows and tiredness and lost friends, I’ve started to think I need a strategy to travel less. Also, my girlfriend is involved in this. Our idea is to let my mind think that I’m travelling though I’m not, by taking long residencies outside Sweden. So now I have a five-month residency in Amsterdam and after that a whole year at the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin programme, a scholarship. It works, in a way. When I went to Amsterdam, I started longing for Sweden as my country. Because I understood I would be away for long, I became homesick for the first time. And when I feel the thirst for travel I can make it subtler, because technically, I am already travelling. Through this, I started travelling less. Now, I travel only twice a month.

When I travel, I bring my laptop. They asked me in India what I would bring if the house were on fire. I said my laptop, because there is another house inside it. What is a home for a Palestinian born in a refugee camp if not language? It’s something I inherited from my father.

He told me about paradise, the land of milk and honey. When I got my Swedish passport, I went to Palestine. There was nothing. No milk and no honey. It’s only in the dream of the Palestinians. The first time I went there, I was held six and a half hours at the airport. With all the happiness and sadness that I had about being there, finally the Israeli let me in. To this day, I never spoke with my father about that, because they threw him out twice, once from Ashkelon to Gaza in 1948, then from Gaza to Egypt in 1967, and he left his mother there. Until 2012 when she died, he didn’t meet her.

Home is connected to the mother tongue. I miss hearing my name. I used to say to God all the time that I miss Syria and Damascus here in Sweden. But when I asked God to connect me with Syria, he must have misunderstood me. Instead of taking me to Syria, he sent the Syrians to me.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am joined today by Jo Jackson, who has kindly come to tell us all about the books she remembers, as part of the blog tour for Beyond the Margin. Many thanks to Jo for taking the time to talk to us, and to Rachel at Rachel’s Random Resources for inviting me to be a part of the blog tour. Without further ado, over to you Jo.

GUEST POST:

Reading is something I have enjoyed all my life. When I talk to friends who say they never read a book I wonder what they do last thing at night, first thing in the morning, on a hot summer’s day in the shade of the lime tree or on cold wet Sunday afternoons when the log burner is on and its cosy inside.

I don’t have shelves of books. I won’t often read a book twice and I believe books are for sharing not for sitting on a dusty shelf. If you’ve read it and enjoyed it, pass it on and when it comes back to you, pass it on again.

My favourite book is God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy and my favourite author is Gerbrand Backer author of The Twin and Ten White Geese. The books below are books I remember for many different reasons.

Heidi by Joanna Spyri. I read this as a child. I no longer own a copy, but I can still see the illustrations so clearly. The beautiful alpine scenery, Heidi’s self-contained grandfather sitting outside his hut. Heidi snuggling into her attic bed. Then there was Clara, the lonely little girl who because of her illness couldn’t run and play and enjoy the flowers and the sunshine as Heidi did. This is essentially a book about love and how it grows when it’s shared. Perhaps it was reading Heidi that made me want to discover other countries and to always feel at home amongst mountains.

As a teenager on one of my regular visits to the library I brought home John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. This was like something I’d never read before set in a landscape quite alien to me. The story depicts the hardships of a family migrating west from the Oklahoma dust bowl. On one level it’s about family unity, on another about exploitation and greed set against growing political unrest and a rising fear of communism. I’m sure I didn’t articulate those points at the time, but I loved Steinbeck’s poetic prose and his imagery. His characters were brilliantly drawn and whilst I was reading it I was part of the family. Fifty years later it’s those characteristics that still draws me to a book. I devoured every one of his novels and by the time I studied Of Mice and Men at school, Lennie was already a character I would never forget. Recently I found To a God Unknown. Written in 1933 and described as literary fantasy it has a haunting spiritualism. It is a beautiful book. The scene in the glade remains forever with me.

In recent years I have travelled to the beautiful country of Ethiopia and on another occasion camped in the Empty Quarter after travelling through the Oman. These places were special to me because I felt I had already been there after reading Wilfred Thesiger’s wonderful travel books. He was born in 1910 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Life of My Choice is an account of his childhood and how, as he grew older, he became repulsed by the trappings of western life. He travelled extensively with the Bedu people and immersed himself in their way of life. His writing is succinct, descriptive and insightful. I suspect he was a troubled man trying to live at a time when having an unconventional personality was not applauded. He would have been difficult to know being controversial in his views and habits. I may not have liked him, but I wish I’d had the opportunity to know him because his books are wonderful.

My final book has a personal story attached but it is a book I believe everyone should read. Mornings in Jenin by Susan Abulhawa was published in 2006 and explores life in post 1948 Palestine. It shows how love and loyalty can survive amongst the horror of war and why the Middle East question remains as insoluble today as it was then.

It is a meaningful book for me because in 1983 my husband and I and our three children were returning to England after living in Egypt for two years. Our plan was to drive back through Israel and take a ferry from Haifa to Venice before driving home through Europe. The journey out of Egypt was complex and ‘making friendships’ a necessary but slow part of the process along the way. The consequence being we were too late in the day to import the car at the Egyptian/ Israeli border and our only option was to take a taxi to the nearest hotel 70 km away. Our taxi driver, a Palestinian, offered instead to take us the short distance to his house near Gaza, let us sleep there and he would bring us back to the border early the next morning to collect our car, all for the price of the taxi fare.

When we arrived his whole extended family were there to greet us. He and his wife gave up their room and their bed and moved mattresses in for our children to sleep on. We had tea and pastries in the courtyard and anyone in the village who could speak a word of English popped in to say hello. At night he and his brother took us out for a meal and wouldn’t allow us to pay. Before we left in the morning, we had to have our photographs taken with each member of the family and his little daughter had proudly put on her best dress for the occasion.

We remember the kindness of that family with such fondness. As we watch the terrible destruction in the Gaza strip, we often think of them and hope their lives have been spared.

Of course there are many more wonderful books I have read but when I set myself this task these were the first ones to spring to mind. Perhaps you will have enjoyed some of them too.

BLURB:

Is living on the edge of society a choice? Or is choice a luxury of the fortunate?

Joe, fighting drug addiction, runs until the sea halts his progress. His is a faltering search for meaningful relationships.

‘Let luck be a friend’, Nuala is told but it had never felt that way. Abandoned at five years old survival means learning not to care. Her only hope is to take control of her own destiny.

The intertwining of their lives makes a compelling story of darkness and light, trauma, loss and second chances.

PURCHASE LINKS:

Amazon UK

Amazon US

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Jo Jackson reads books and writes them too.

Having worked with some of the most vulnerable people in society she has a unique voice apparent in her second novel Beyond the Margin.

She was a nurse, midwife and family psychotherapist and now lives in rural Shropshire with her husband. She loves travelling and walking as well as gardening, philosophy and art.

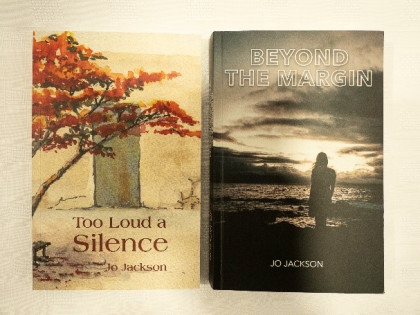

Her first novel Too Loud a Silence is set in Egypt where Jo lived for a few years with her husband and three children. Events there were the inspiration for her book which she describes as ‘a story she had to write’.

SOCIAL MEDIA:

Facebook

Twitter

Website

GIVEAWAY:

Win signed copies of Beyond the Margin and Too Loud a Silence by Jo Jackson. (UK only)

*Terms and Conditions –UK entries welcome. Please enter using the Rafflecopter link below. The winner will be selected at random via Rafflecopter from all valid entries and will be notified by Twitter and/or email. If no response is received within 7 days then Rachel’s Random Resources reserves the right to select an alternative winner. Open to all entrants aged 18 or over. Any personal data given as part of the competition entry is used for this purpose only and will not be shared with third parties, with the exception of the winners’ information. This will passed to the giveaway organiser and used only for fulfilment of the prize, after which time Rachel’s Random Resources will delete the data. I am not responsible for despatch or delivery of the prize.

ENTER HERE

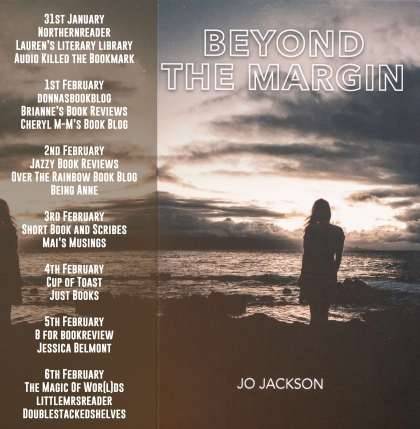

To find out more about Beyond the Margin, have a look at the other blogs taking part in the tour.

@jojackson589 joins me today to talk about some of her favourite books as part of the #blogtour for #beyondthemargin @rararesources #guestpost #bookblogger #fictioncafewriters #spoonshortagebookclub I am joined today by Jo Jackson, who has kindly come to tell us all about the books she remembers, as part of the blog tour for Beyond the Margin.

0 notes

Text

Mozambique: Where HIV Patients Who Have Nowhere to Go Go | Future Planet

At 44 years old, Pauline (*) knew nothing of any crisis. Her four children were healthy and she had a job as a domestic servant at the former governor's daughter's home. It was a demanding life, at six thirty in the morning already in charge of passing the dust and preparing breakfast for others who were not her children, but on her side of Mozambique lives are born like this. “I was fine. He could do anything, however heavy it was. I was just a little magriña. I would wear a dress and a few days later I would have to fix it because it no longer worked for me ”.

On the morning of 2007, when everything stopped being the way it had always been, Pauline got up before the sun, around four, to get 20 kilos of millet ready before going to work. When his shift was over, he would go to the health center to ask about that constant weight loss. “There was some xima —A traditional dish made from corn flour — from the previous day, so the girl would have something to eat even if I came back late. ” In Mozambique one can know the beginning of things, but rarely their end. That afternoon, a nurse looked at his eyes, the ganglia, the shrunken skin.

“You are not feeling well. She is infected with HIV, ”said the doctor after submitting her to medical examinations.

Pauline denied in duplicate. She did not use drugs, nor had there been any other men since her husband's death. Those, they said in massive government campaigns to raise awareness of a population reluctant at the time to be tested, were the most common forms of infection. She was neither in pain nor had she lost an iota of strength. He had only lost 15 kilos.

For not arguing with someone wearing a white coat, Pauline, a mother of four and a sister of 15 in the Gaza border province, took what the doctor told her. 12 hours later, he was back. “I started having diarrhea and feeling bad. I couldn't even stand up. I had to crawl up there. ” Neighbors watched her crawl. No one came to help her. The doctors made him a plaque. I had a major spill.

Mozambique has increased coverage of antiretroviral treatments from 12% to 54% of the affected population between 2010 and 2017 and reduced deaths by 46%

“You have advanced HIV. Your body has little to fight with, so it has scrambled. ”

His CD4 count, the white blood cells that fight infection, hovered around 80 per cubic millimeter. The recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO) at that time was to start treatment when it was less than 300 – today it is urged to treat all patients regardless of their CD4 or when it is below 500 in areas with access limited to antiretroviral treatments. Pauline was immediately booked at the Alto-Maé Reference Center (CRAM). One of those places that those with no place to go go to.

The 90-90-90 margins

From the first hour, the streets of the Cidade de Cimento ooze life. There are queues of university students at the panzinhos. Queues of vehicles to turn the avenue. Plastic queues and memory on the buses and vans that take and bring to Mozambique from Canico. Sooner or later, the queues always pass through the Alto Mae.

The health center is the hub of the city's health system. A succession of sober buildings, somewhat old but always spotless, where nothing is superfluous. Much less space. The waiting rooms are crowded and the health system is not over the top: the advances in health, summarized in the increase in life expectancy in 10 years, up to 58, since 2000, are amazing, but still insufficient. There is less than one bed available for every 1,000 inhabitants and one doctor for every 5,000.

CRAM laboratory technicians performing an HIV test. P. L. O.

One of them, Dr. Gil, is caring for a young man in the last of the buildings of the healthcare complex. Although the architectural geography is identical, this is a different place. CRAM is the last HIV station in Mozambique. “Here we serve the most vulnerable groups, that part of the forgotten population that does not receive any type of assistance,” explains Ana Gabriela Gutierrez, one of the heads of the center launched by Doctors Without Borders in collaboration with the Ministry of Health. .

The healthcare model implemented by the Government following the UNAIDS guidelines 90-90-90 —90% of those infected know their diagnosis, 90% of them receive treatment and 90% of those who receive it reach an undetectable viral load— It has been a success capable of increasing the coverage of antiretroviral treatments from 12% to 54% of the affected population between 2010 and 2017 and of reducing deaths related to the disease by 46%, but it has its margins. Drug users and people with HIV advancing, those with resistance to treatment, Kaposi's sarcoma or opportunistic ailments such as tuberculosis, which is the disease that most kills HIV patients in Mozambique. Those are the CRAM patients.

Currently, the center assists more than 2,500 people, some with up to 10 years of follow-up. Every year, they add an average of 800 new patients. “Some”, says Dr. Gutiérrez, “arrive without symptoms, not even fever, because their bodies are no longer capable of responding to the virus.” Pauline was one of them.

Worse than disease, stigma

Before facing the virus it is necessary to defeat the stigma that surrounds it. “For a long time, HIV was explained as an equation equal to death, and linked to promiscuity,” says Ana Patricia Silva, the coordinator of the MSF psychological program at CRAM.

When Pauline came HIV was still a life sentence. A reason to lose your job or a husband; to be the talk of the neighborhood. “I didn't want to tell anyone, in fact, my little daughter still doesn't know, and I told the three oldest two years ago. I wanted to remain free. Then I had a stroke of fortune: a neighbor was also in the CRAM accompanied his blind sister to receive treatment. If he talked about me, I would talk about them, “he continues. This is how Pauline got your confidant that then, given the high dropout rate, was required to enter the program. It could be a family member, a friend, or a trusted neighbor.

In just 15 days Pauline gained weight and her health improved considerably. I had to take two pills, one at 8:00 and the other at 20:00. The first hour, could not always. “In the house where I worked, you had to leave your bag at the entrance and we couldn't go back to the box office all day. If we did they thought we wanted to steal. So half the days I only took the pill at night. “

When Pauline arrived at the center, HIV was still a life sentence. A reason to lose your job or a husband; to be the talk of the neighborhood

Without knowing it, she had a relapse. Although he did not cough either, he had associated tuberculosis. “One day I fell at work. They told me to go rest. Before going back, I went through the market, but I fell again. A young woman from the neighborhood took me home. The next day I went back to work. 'Go until you recover,' they told me when I fell back down. I was taking the treatment, I was sure it couldn't be due to HIV. ”

Only 54% of the 1.8 million people with HIV in Mozambique receive antiretroviral treatment, and not all follow medical prescriptions. Some because of hunger. Others out of fear. “One of the reasons why in many cases CD4 does not go back is poverty. Here people live day by day, they cannot think about what they will eat tomorrow. Many times they are not aware of what the disease means and only go to the doctor or take the treatment when they feel bad, “emphasizes Dr. Gutiérrez. In Mai Coragem, a play that has rocked consciences in the country, a mother asks her daughter why she has become an alcoholic. “Because I couldn't count that I had HIV.” Only then does his uncle take the floor: “I am also HIV positive.”

The vast majority of families today have a member affected by the disease. That has managed to downgrade malicious comments, but it has not ended discrimination. The third time that Pauline's strength at the employers' house failed, her tray with food falling off, she was fired. The next eight months he spent by the railing, looking for the air denied by tuberculosis. “Without work, at that time I had a hard time, I hardly had anything to eat.” At home they survived on what their older children contributed. But these had a question. How had his mother been infected?

“One day I went to get the Bible and when I opened it I found the green cardboard that was given to people with HIV at that time. I showed it to my children: ‘Come, I was not with anyone. It was his father. ’ They asked me for forgiveness and I did not want to continue stirring the dead. “

This toxic masculinity is widespread in the country. Husbands who take the treatment when they consider it appropriate, but do not tell their wives. “Men have economic power and feel they are in control of the situation,” says the CRAM psychologist. “Rabies?” Pauline intervenes, “no, really what I feel sorry for. If he had told me, we would both have gone to take the treatment and he would still be alive. But since he did not speak… ”

Overcome family fear, Pauline had to defeat the virus. His CD4 had dropped back to 100 per cubic millimeter. I was vomiting and had diarrhea. After two years of treatment, something was wrong.

“You have entered into failure.”

The short answer, the long answer

CRAM has a binary soul. It has a hectic rhythm, that of survival, which is agitated with each new patient. “Early diagnosis is very important, it is what can make a difference,” explains Dr. Gutiérrez. The small laboratory built in the shadow of the main building is the heart of the project: it produces kidney, liver profiles, measures CD4, or possible infections of malaria, syphilis and hepatitis, as well as rapid tests for opportunistic infections such as cryptococcal meningitis. “It is what allows us to give a different response, to implement key treatments,” insist those responsible for MSF at the center.

In less than 24 hours, the patients who attend the CRAM are already receiving the clinical assistance they require. In urgent cases, in less than four. Rapid tests for HIV in the blood or tuberculosis in the urine (TBLAM) are decisive in saving lives today.

It is about recovering the CD4 level of patients and preventing them from dying from opportunistic diseases. “The objective”, summarizes Dr. Gutiérrez, “is that the viral load is undetectable because then it is no longer transmissible.” Achieving this requires a long-term look. A personalized follow-up to adapt to the evolution of the disease. When Pauline's initial treatment stopped working, they started a second-line combination. “I recovered very quickly, going from 200 to 800 CD4 in no time.”

Exterior view of the Alto-Maé Reference Center. P. L. O.

Of the advancing HIV patients seen by the hospital, 60% receive this second-line treatment. 10%, third. In the absence of CRAM, the vast majority of them would have died when the initial treatment was no longer effective. Even Kaposi's sarcoma is no longer synonymous with death thanks to the chemotherapy program launched. The Government has noted the success of this model and second-line treatments for HIV patients are currently available in most public health units.

Today Pauline is a chef at a downtown restaurant. Her bosses are unaware of her status, “they still don't want anyone like that working in the kitchen”, but she has no moral concern: firstly, because, although a large part of society still doubts, the virus is not transmitted by the manipulation of foods. Second, because your viral load is no longer detectable. ‘Undetectable = untransmissible’. In fact, the CRAM viral suppression statistic is excellent: 84% in the second line; 77% in third.

With the current medication, Pauline does not have to worry about a thing. It is enough to take your treatment in the morning, before going to work. “I don't even remember that I'm sick.”

(*) The name has been modified to preserve its identity.

You can follow FUTURE PLANET at Twitter and Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe here to our newsletter.

The post Mozambique: Where HIV Patients Who Have Nowhere to Go Go | Future Planet appeared first on Cryptodictation.

from WordPress https://cryptodictation.com/2020/03/31/mozambique-where-hiv-patients-who-have-nowhere-to-go-go-future-planet/

0 notes

Text

We can wipe out poverty in 1 generation. So what’s holding us back? Greed, maybe?

How We Can Make God, and Each Other,

Happy by Ending Poverty

by Pastor Paul J. Bern

For better phone, tablet or website viewing, click here :-)

Today in the early 21st century, and with 99% of the wealth in America in the hands of 1% of the population, the US has a bigger and wider gap between the richest 1% of American money earners and big business owners and the remainder of working Americans than there is in many supposedly “third world” countries. The widespread and systemic unemployment or underemployment that currently exists in the US job market (including those who have given up and dropped out of the job market) is no longer just an economic problem. It has become a civil rights issue of the highest priority. The US job market has been turned into a raffle, where one lucky person gets the job while entire groups of others get left out in the cold – sometimes literally. I am vigorously maintaining that every human being has the basic, God-given right to a livelihood and to a living wage. There is no such thing under God's laws that say any given person should be unable to support themselves and their families! Anything less becomes a gross civil rights violation. Based on that, I would say those jobless individuals are victims of systemic economic discrimination. And so I further state unreservedly that restarting the civil rights era protests, demonstrations, sit-ins and the occupation of government buildings, or whole city blocks, is the most effective way of addressing the rampant inequality and persistent economic hardship that currently exists in the US.

Fortunately, this has already started here in the US, with the advent of the protests for so many unarmed Black men being killed by police officers. But these protesters are actually somewhat behind the curve. Because, before them there was Occupy Wall St., “we are the 99%” and Anonymous. And before those there was the Arab Spring in Egypt, the summer of 2011 in Great Britain and Greece, plus Libya, Syria and Gaza in the Middle East. So from a political standpoint, the current crop of protesters here in the US have some catching up to do. And yet, that was before the rest of the world got on board protesting globally for the many murdered Americans in Florida, Missouri, New York and elsewhere. So now, like an echo from the fairly recent past, the protests over police violence has echoed across the globe and is still reaching a crescendo.

The least common denominator to all this rage in the streets is that of being economically disadvantaged. “You will always have the poor”, Jesus said, “but you will not always have me” (This was prior to his being crucified). Deuteronomy chapter 15, verses 7-8 state, “If there is a poor man among your brothers.... do not be hardhearted or tightfisted toward your brother. Rather be open handed and freely lend him whatever he needs.” People everywhere find themselves surrounded by wealth and opulence, luxury and self-indulgence, while they are themselves isolated from it. It is one thing to be rewarded for success and a job well done. But it's an altogether different matter to have obscene riches flaunted in your face on a daily basis in order to remind certain people of their alleged inferiority. I think what we really need to do is find a way to end poverty. I can sum up the answer in two words: Free Education. Otherwise those who are poor will always remain so.

Who’s responsible for the poor? Back in the reign of the first Queen Elizabeth, English lawmakers said it was the government and taxpayers. They introduced the compulsory “poor tax” of 1572 to provide peasants with cash and a “parish loaf.” The world’s first-ever public relief system did more than feed the poor: It helped fuel economic growth because peasants could risk leaving the land to look for work in town. By the early 19th century, though, a backlash had set in. English spending on the poor was slashed from 2 percent to 1 percent of national income, and indigent families were locked up in parish workhouses. In 1839, the fictional hero of Oliver Twist, a child laborer who became a symbol of the neglect and exploitation of the times, famously raised his bowl of gruel and said, “Please, sir, I want some more.” Today, child benefits, winter fuel payments, housing support and guaranteed minimum pensions for the elderly are common practice in Britain and other industrialized countries. But it’s only recently that the right to an adequate standard of living has begun to be extended to the poor of the developing world.

In an urgent 2010 book, “Just Give Money to the Poor: The Development Revolution from the Global South”, three British scholars showed how the developing countries are reducing poverty by making cash payments to the poor from their national budgets. At least 45 developing nations now provide social pensions or grants to 110 million impoverished families — not in the form of charitable donations or emergency handouts or temporary safety nets but as a kind of social security. Often, there are no strings attached. It’s a direct challenge to a foreign aid industry that, in the view of the authors, “thrives on complexity and mystification, with highly paid consultants designing ever more complicated projects for the poor” even as it imposes free-market policies that marginalize the poor. “A quiet revolution is taking place based on the realization that you cannot pull yourself up by your bootstraps if you have no boots,” the book says. “And giving ‘boots’ to people with little money does not make them lazy or reluctant to work; rather, just the opposite happens. A small guaranteed income provides a foundation that enables people to transform their own lives.”

There are plenty of skeptics of the cash transfer approach. For more than half a century, the foreign aid industry has been built on the belief that international agencies, and not the citizens of poor countries or the poor among them, are best equipped to eradicate poverty. Critics concede that foreign aid may have failed, but they say it’s because poor countries are misusing the money. In their view, the best prescription for the developing world is a dose of discipline in the form of strict “good governance” conditions on aid. According to The World Bank, nearly half the world’s population lives below the international poverty line of $2 per day. As the authors of Just Give Money point out, that’s despite decades of top-down, neo-liberal, extreme free-trade policies that were supposed to “lift all boats.” In Africa, South Asia and other regions of the developing “South,” the situation remains dire. Every year, according to the United Nations, more than 9 million children die before they reach the age of 5, and malnutrition is the cause of a third of these early deaths.

Just Give Money argues that cash transfers can solve three problems because they enable families to eat better, send their children to school and put a little money into their farms and small businesses. The programs work best, the authors say, if they are offered broadly to the poor and not exclusively to the most destitute. “The key is to trust poor people and directly give them cash — not vouchers or projects or temporary welfare, but money they can invest and use and be sure of,” the authors say. “Cash transfers are a key part of the ladder that equips people to climb out of the poverty trap.” Brazil, a leader of this growing movement, provides pensions and grants to 74 million poor people, or 39 percent of its population. The cost is $31 billion, or about 1.5 percent of Brazil’s gross domestic product. Eligibility for the family grant is linked to the minimum wage, and the poorest receive $31 monthly. As a result, Brazil has seen its poverty rate drop from 28 percent in 2000 to 17 percent in 2008. Data released on December 15th, 2017 by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) shows that nearly fifty million Brazilians, or just over 20 percent of the population, live below the poverty line, and have family incomes of R$387.07 per month – approximately $5.50 a day USD. In northeastern Brazil, the poorest region of the country, child malnutrition was reduced by nearly half, and school registration increased.

South Africa, one of the world’s biggest spenders on the poor, allocates $9 billion, or 3.5 percent of its GDP, to provide a pension to 85 percent of its older people, plus a $27 monthly cash benefit to 55 percent of its children. Studies show that South African children born after the benefits became available are significantly taller, on average, than children who were born before. “None of this is because an NGO worker came to the village and told people how to eat better or that they should go to a clinic when they were ill,” the book says. “People in the community already knew that, but they never had enough money to buy adequate food or pay the clinic fee.” In Mexico, an average grant of $38 monthly goes to 22 percent of the population. The cost is $4 billion, or 0.3 percent of Mexico’s GDP. Part of the money is for children who stay in school: The longer they stay, the larger the grant. Studies show that the families receiving these benefits eat more fruit, vegetables and meat, and get sick less often. In rural Mexico, high school enrollment has doubled, and more girls are attending.

India guarantees 100 days of wages to rural households for unskilled labor, paying at least $1.25 per day. If no work is available, applicants are still guaranteed the minimum. This modified “workfare” program helps small farmers survive during the slack season. Far from being unproductive, the book says, money spent on the poor stimulates the economy “because local people sell more, earn more and buy more from their neighbors, creating the rising spiral.” Pensioner households in South Africa, many of them covering three generations, have more working people than households without a pension. A grandmother with a pension can take care of a grandchild while the mother looks for work. Ethiopia pays $1 per day for five days of work on public works projects per month to people in poor districts between January and June, when farm jobs are scarcer. By 2008, the program was reaching more than 7 million people per year, making it the second largest in sub-Saharan Africa, after South Africa. Ethiopian recipients of cash transfers buy more fertilizer and use higher-yielding seeds.

In other words, without any advice from aid agencies, government, or nongovernmental organizations, poor people already know how to make profitable investments. They simply did not have the cash and could not borrow the small amounts of money they needed. A good way for donor countries to help is to give aid as “general budget support,” funneling cash for the poor directly into government coffers. Cash transfers are not a magic bullet. Just Give Money notes that 70 percent of the 12 million South Africans who receive social grants are still living below the poverty line. In Brazil, the grants do not increase vaccinations or prenatal care because the poor don’t have access to health care. A scarcity of jobs in Mexico has forced millions of people to emigrate to the U.S. to find work. Just Give Money emphasizes that to truly lift the poor out of poverty, governments also must tackle discrimination and invest in health, education and infrastructure.

The notion that the poor are to blame for their poverty persists in affluent nations today and has been especially strong in the United States. Studies by the World Values Survey between 1995 and 2000 showed that 61 percent of Americans believed the poor were lazy and lacked willpower. Only 13 percent said an unfair society was to blame. But what would Americans say now, in the wake of the housing market collapse, the bailout of the banks and the phony economic “recovery”? The jobs-creating stimulus bill, the expansion of food stamp programs and unemployment benefits — these are all forms of cash transfers to the needy. I would say that cash helps people see a way out, no matter where they live. Not only that, the Bible condemns those who refuse to help the poor, as it is written in the Book of Proverbs: “He who oppresses the poor shows contempt for their maker” (chapter 14: 31), and again it is written, “Rich and poor have this in common: The same Almighty God has made them both.” (chapter 22: 2).

0 notes