#In the parliamentary history of Uttar Pradesh

Text

Honoring a Stalwart: Lal Krishna Advani Receives Bharat Ratna

In a momentous announcement, the Indian government has decided to confer the prestigious Bharat Ratna upon Senior BJP Leader Lal Krishna Advani. This honor comes amidst the nation's jubilation following the consecration of the Ram temple in India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed his delight in sharing the news, acknowledging Advani's monumental contribution to India's development. As the man behind the Ram Janambhoomi movement, Advani's role has been pivotal in shaping India's political landscape.

Advani's journey, spanning nearly a century, embodies dedication and selfless service to the nation. Born in Karachi in 1927, his early years were marked by the turbulence of India's partition. Despite the upheaval, Advani's commitment to a more secular India remained steadfast. His association with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) from a young age instilled in him the motto 'idam-na-mama' - 'This life is not mine, my life is for my nation'.

As BJP Chief in 1989, Advani spearheaded the party's Mandir pledge, setting the stage for his iconic 'Rath Yatra' in 1990. This journey from Somnath in Gujarat to Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh galvanized support for the construction of the Ram temple and reshaped Indian politics. The BJP's electoral fortunes surged under Advani's leadership, culminating in significant gains in the 1996 elections. This marked a watershed moment in Indian democracy, with the BJP emerging as the single largest party in the Lok Sabha.

Advani's parliamentary career, spanning nearly three decades, saw him hold key positions in the government, including Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister during Atal Bihari Vajpayee's tenure. His leadership played a pivotal role in advancing the party's ideology and agenda.

Acknowledging the honor bestowed upon him, Advani emphasized that the Bharat Ratna is not just a personal accolade but a recognition of the ideals and principles he has espoused throughout his life. His unwavering commitment to the nation has been the guiding force behind his actions, from grassroots activism to serving at the highest echelons of government.

Prime Minister Modi hailed Advani's contribution as exemplary, noting his tireless efforts in championing the ethos of 'nation first'. In bestowing the Bharat Ratna upon Advani, the government not only honors his individual achievements but also pays tribute to the millions of BJP workers and leaders who have tirelessly worked towards advancing the party's ideologies.

Advani's journey is a testament to the resilience and fortitude of India's political landscape. From the tumultuous days of partition to the present, he has remained steadfast in his commitment to serving the nation. His leadership has inspired generations of Indians and left an indelible mark on the country's political history.

In conclusion, Lal Krishna Advani's elevation to the ranks of Bharat Ratna is a fitting tribute to his unparalleled contribution to Indian politics. His life story serves as a beacon of hope and inspiration, reminding us of the power of dedication, integrity, and unwavering commitment to the nation. As India celebrates this momentous occasion, it honors not just one man but the enduring spirit of service and sacrifice that defines the nation.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Two years from now, India will hold the most consequential election in its history: the final chance to stop Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s conversion of the world’s largest democracy into an illiberal Hindu-supremacist state. But the vote that may determine the outcome of that election takes place on Oct. 17, when the opposition Indian National Congress party will pick a new leader through an internal election for the first time since 2000.

The secular alternative to Modi’s Hindu-first Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Congress is the only outfit that can match the ruling party’s national recognition and organizational reach. If there is a force that can deny Modi another outright majority in India’s Parliament, if not defeat him squarely, it is Congress. Alas, India’s grand old party has become debilitated by a democratic deficit of its own.

Congress—the party that once negotiated India’s freedom from British rule, inspired a generation of anti-colonial leaders from Asia to Africa, and incubated India’s democratic institutions—has effectively functioned as a hereditary dictatorship led by the Gandhi family for more than five decades. Its degeneration began in the 1960s, when then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi purged her rivals and built a personality cult around herself, reducing the Congress party to her family’s fief. Since then, barring a brief interregnum in the 1990s caused by a death in the family, the Indian National Congress has not known a single leader outside the Gandhi dynasty.

Even now, when the party should be concentrating its energies on choosing the best candidate to lead the fight against Modi in 2024, its leadership race has been eclipsed by a 150-day so-called unity march led by politician Rahul Gandhi. The procession, staged as an historic event, is mostly a means to repair the tattered reputation of Rahul, the fifth-generation family scion who led Congress’s campaigns in parliamentary elections in 2014 and as the party’s president until 2019. Both were resounding victories for the BJP. Rahul even lost the family’s pocket borough in its stronghold in Uttar Pradesh in 2019 and carpetbagged his way into Parliament from southern India at the expense of the left.

Having delivered an electoral calamity for his party in 2019, Rahul did nothing to redeem himself. Between 2015 and 2019, as Modi intensified India’s social transformation—subverting autonomous institutions, consolidating a personality cult, and mainstreaming violent Hindu supremacy—Rahul made 247 overseas trips, an average of about five per month. He was missing on virtually every occasion that Modi’s actions created an opening for the opposition to advance a robust response. As a backbencher, he rarely attends Parliament, asks few questions (he raised none during Modi’s first term), and routinely misses meetings of parliamentary committees.

Despite resigning from the party’s presidency in 2019, Rahul remains its de facto leader , whereas his mother, Sonia Gandhi, wields power as caretaker president. The only significant promotion within the party leadership since 2019 has been of his sister, Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, who has no prior political experience. This state of affairs has allowed Modi, a self-made politician raised by lower-caste parents, to cast himself as the righteous nemesis of the culture of entitlement exemplified by the Gandhis. Modi has portrayed Congress as irredeemably nepotistic and sought to discredit the secular nationalism the party claims to espouse.

None of this has provoked Congress to shed the family dynasty. If anything, criticism of the Gandhis within the party is punished in petty ways. In 2020, when a group of senior leaders urged internal reform, its members were vilified, told to leave the party, and shut out of party posts. The party’s highest administrative body, handpicked by the Gandhis, then passed a motion to strengthen the family’s grip and see off all challenges to its reign. In state elections months later, Congress lost control of one state to the BJP and was routed in others.

Once invincible across India, Congress now governs only two of India’s 28 states. Several experienced and promising young party leaders have left in frustration over the lack of direction under the Gandhis. The family doles out party positions, an arrangement that has ensured its control. But the party’s woes forced the Gandhis to agree to this month’s competitive vote, and Rahul has decided to keep out of the race. His decision has three intended ends: covering up the taint of dynasticism; making Rahul appear self-sacrificing, a patriot uninterested in position; and consecrating him within the party as the supreme authority who does not need a formal title to exercise power.

To avoid an unexpected challenge to their authority, the Gandhi family has nominated a surrogate to contest the party leadership election. Their stand-in is Mallikarjun Kharge, an eminence from southern India who overcame the vicious prejudices directed at him for being a Dalit—a member of a community deemed so impure by the scriptures that they fall outside the hierarchical Hindu caste system—to raise himself up. Worryingly, Kharge is also an obedient 80-year-old Gandhi family acolyte who lost his parliamentary seat in the last election.

His lone challenger is Shashi Tharoor, a member of a dominant yet—strictly speaking—lower caste from southern India. He is perhaps the only figure with the oratorical prowess, charisma, and national profile to rival Modi. As a former high-ranking career diplomat at the United Nations, Tharoor oversaw a complex bureaucracy, supervised efforts to rescue refugees who fled Vietnam by ship and boat at the end of the Vietnam War, helped negotiate the end of hostilities in the former Yugoslavia, and finished close behind Ban Ki-moon in the race for U.N. secretary-general in 2006. An astringent critic of Hindu nationalism, Tharoor has won three successive terms in Parliament despite running in the communist redoubt of Kerala.

Tharoor would be a front-runner to lead almost any centrist party in the world. In the Congress party, however, he faces abuse because he threatens to overshadow Rahul. The party that admires Kharge for his docility portrays Tharoor as a renegade for dissenting from the Gandhi leadership and calling for reforms to democratize the party. Tharoor may be just the disruptive break from the past that Congress needs, but the party appears determined to thwart him. Kharge admitted to advising Tharoor to drop out rather than squander his time on an election. Although Tharoor has traversed the country on budget airlines, Kharge has flown around India on a private plane.

Undeterred, Tharoor has published a detailed blueprint to revitalize Congress. But he faces nearly impossible odds against Kharge, the status quo candidate. Party bosses have turned an indulgent blind eye to officials who have deployed their authority to mobilize support for Kharge—in blatant violation of the election code. Tharoor has even been denied a complete list of the 9,000 eligible voters and their contact details. The results of the election are expected on Oct. 19.

Modi’s “New India” is now widely regarded as the site of democracy’s demise, but it is also paradoxically the setting for democracy’s civic reclamation. From massive nationwide agitation against 2019 legislation that sought to introduce a religious test for citizenship (which has not yet been implemented) to the unremitting protests against controversial agricultural laws that culminated in their repeal last year, the past three years have also been characterized by citizen uprisings against Modi’s sectarian politics.

In “any unrigged pan-Indian electoral college that we can imagine,” the historian Mukul Kesavan recently wrote in Calcutta’s Telegraph, “Tharoor would handily best Kharge.” A victory for Tharoor could boost the party’s sinking fortunes by heralding a departure from its recent decline. Tharoor still may succeed in unifying a fragmented opposition that is weary of the Gandhis. Even if such a coalition cannot vanquish the BJP, it could deprive it of a full majority in Parliament and force it to form a coalition government. Modi is unaccustomed to sharing power, and any such arrangement could temper his worst instincts—if not finish him off completely. But since such a future would be predicated on a reformed Indian National Congress party—and since reform would threaten the Gandhis—a coordinated effort is underway to foil Tharoor’s bid.

What distinguishes India today is not the presence of a strongman leader; it is the absence of an effective opposition capable of converting ordinary citizens’ fury into electoral gains. The Congress party’s leadership election presents the first real opportunity in eight years to end Modi’s attacks on Indian democracy, but the country’s oldest political party appears determined to foil that opportunity. Emancipating Congress from the Gandhis may prove even more challenging than rescuing India from Modi.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) have recommended downgrading India's designation to "Countries with Particular Concern" due to deteriorating conditions of Religious Freedom under the extremist BJP government.

USCIRF is not the only watchdog to have raised this concern and brought attention of the international community towards the crisis situation of religious freedom and the plight of minorities, specially Muslims in India under the current extremist hindutva government led by Narendra Modi.

In July 2019, the United Nations experts expressed their grave concern over the ongoing update of the National Register of Citizens in Assam, India, and its potential to harm millions of people, most of whom belong to minorities. The experts issued warnings on the rise of hate speech directed against these minorities in social media, and the potential destabilizing effects of the marginalization and uncertainties facing millions in this part of the country. In June 2018, more than 4 million people in Assam were excluded from the amended draft National Register of Citizens (NRC) list, in particular Muslims and Hindus of Bengali descent. United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteurs warned that exclusion from the NRC could result in “statelessness, deportation, or pro-longed detention.” and with Home Minister Amit Shah refering to migrants as “termites” to promising to throw them into Bay of Bengal the situation is bleak for these minorities.

It is also not the first time USCIRF have raised this issue, previously in December 2019 the USCIRF suggested sanctions against Indian leadership if the Citizen Amendment Bill (now Act) is passed. In a statement issued in December they said "if the CAB passes in both houses of parliament, the United States government should consider sanctions against the Home Minister and other principal leadership." UNCIRF along with other relevant bodies have been condemning what have happened in India ever since. The country that have claimed itself to be a secular state have seen severe backlash from international community, calling for it to be black listed for violation of religious freedom rights and called as "dangerous for minorities".

In a detailed report published by USCIRF they reported "religious freedom conditions in India experienced a drastic turn downward, with religious minorities under increasing assault. Following the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) re-election in May, the national government used its strengthened parliamentary majority to institute national level policies violating religious freedom across India, especially for Muslims".

Things took a turn for worst in past few months after passing of Citizen Amendment Act. The CAA’s passage in December sparked nationwide protests that police and government aligned groups met with violence; in Uttar Pradesh (UP), the BJP chief minister Yogi Adityanath pledged “revenge” against anti-CAA protestors and stated they should be fed “bullets not biryani.” In December, close to 25 people died in attacks against protestors and universities in UP alone. According to reports, police action specifically targeted Muslims.

Even though this is all came to light mainly after CAA but the history is of India which claims to be a secular state is filled with violence against minorities. Whether it be the communal violence of 1969 (around 700 Muslims killed in a week) or 2002 Gujrat riots where over a 2000 Muslims were killed. In 1984 there riots against Sikh community claimed lives of around 8000-17000 people and the Indian government arrested about 150000 people without due process. Christian churches have been ransacked and Christians forcibly converted to Hinduism. In October 2008 Pope Benedict XVI criticized the continuing anti-Christian violence in India, the Vatican called for an end to the religious violence in Orissa. Even Hindu dalits have been oppressed and subjected to violation of Human Rights in India. The Cow slaughter law and forces conversions have been a tormenting reality for Muslim minority of India where people have been lynched and murdered in front or law enforcement authorities by angry Hindu mobs.

0 notes

Text

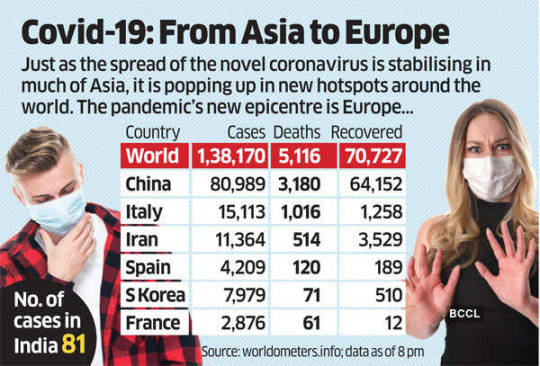

Coronavirus in India: Death toll at 2; States get into lockdown mode

New Post has been published on https://apzweb.com/coronavirus-in-india-death-toll-at-2-states-get-into-lockdown-mode/

Coronavirus in India: Death toll at 2; States get into lockdown mode

New Delhi | Mumbai: A 69-year-old woman from west Delhi suffering from Covid-19 died on Friday, taking the toll to two a day after Karnataka confirmed death of a 76-year-old man on Thursday.

The number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in India rose to 81 and state governments around the country went into battle mode, closing schools and colleges, entertainment venues and malls. Experts said the next month will be vital in determining whether community transmission will happen in the country.

High-profile events like the Indian Premier League (IPL) was postponed by two weeks, while novel coronavirus-related disruptions continued in sectors like aviation and restaurants, as well in bluechip institutions like IIMs, which postponed foreign faculty intakes and cancelled many campus events.

Experts at the Indian Council of Medical Research said community transmission — the disease spreading from people with no travel history to severely affected countries — has to be taken seriously after India has reported two deaths. In Karnataka’s Kalaburagi town, 46 people who were in direct contact with the elderly man who died on Tuesday night were placed under quarantine.

FM, CEA Strike a Positive Note

There was some good news, too. All 112 people admitted to an ITBP quarantine facility in Delhi for over a fortnight tested negative for the novel coronavirus. All of them were evacuated last month from Wuhan in China.

Both finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman and chief economic advisor K Subramanian struck a note of optimism saying the government was in full engagement mode with the industry as well as the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for any specific or broadbased policy response that may be required. Prime Minister Narendra Modi called for a SAARC-wide coordinated response.

“Each department is spending a lot of time to see how best relief can be given,” the FM said, while the CEA said “markets are not reflecting India’s economic fundamentals”.

Army sources told PTI that a man who had returned from Italy this week tested positive at the force’s Manesar quarantine facility in Haryana. Officials in Maharashtra also said two more in Nagpur tested positive for the disease.

Union health ministry officials did not immediately confirm the cases in Maharashtra and Manesar. Giving a breakup, the health ministry said Delhi has reported six positive cases and Uttar Pradesh 10. Karnataka has five patients, Maharashtra 11 and Ladakh three suffering from Covid-19.

Rajasthan, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Jammu and Kashmir, Andhra Pradesh and Punjab have reported one case each. Kerala has recorded 17 cases, including three patients discharged last month after they recovered from the contagious infection with flu-like symptoms. The confirmed cases include 17 foreigners — 16 Italian tourists and a Canadian who was in Uttar Pradesh.

PARLIAMENT SESSION TO GO ON

Responding to speculation over the ongoing Budget Session being shortened, Union parliamentary affairs minister Pralhad Joshi told PTI, “There is no question of curtailing the session.”

While states such as Karnataka, Odisha, Delhi, Bihar and Maharashtra went into virtual shutdown mode, others like Jharkhand, Haryana and Punjab have taken similar precautionary measures.

The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) deferred this year’s IPL cricket tournament from March 29 to April 15. “The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) has decided to suspend IPL 2020 till 15th April 2020, as a precautionary measure against the ongoing novel coronavirus (COVID-19) situation,” said BCCI secretary Jay Shah in a statement.

India’s remaining two one-day matches against South Africa have also been cancelled.

The decision came hours after the Delhi government, which on Thursday announced that schools, colleges and cinema halls would be shut till March 31, said it was also stopping all sports gatherings, including IPL 2020. Jawaharlal Nehru University and Jamia Millia Islamia have suspended classes for now.

Karnataka chief minister BS Yediyurappa on Friday announced a lockdown of universities, malls, cinema theatres, pubs and night clubs for a week and instructed against holding exhibitions, conferences, marriage and birthday parties.

Maharashtra followed suit on the same day with CM Uddhav Thackeray ordering closure of all theatres, gyms, swimming pools, auditoriums from Friday midnight in Mumbai, Pune, Pimpri Chinchwad, Navi Mumbai, Thane and Nagpur.

Airlines reported high numbers of cancellations for domestic flights and expect worse in days to come. And many are shelving plans for leasing aircraft. And India’s restaurateurs have asked the industry body to negotiate with local authorities and malls to reduce payment obligations like rents, given the steep fall in business.

if(geolocation && geolocation != 5 && (typeof skip == 'undefined' || typeof skip.fbevents == 'undefined')) !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', 'https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); fbq('init', '338698809636220'); fbq('track', 'PageView');

Source link

0 notes

Text

Fourth and Fifth Amendment Act, 1955

This article is written by Shanvi Aggarwal, student of (School of Law, Christ Deemed to be University, Bengaluru).

All persons in positions of power ought to be strongly and lawfully impressed with an idea that “they act in trust,” and must account for their conduct to one great master, to those in whom the political sovereignty rests, the people.

– Edmund Burke

Introduction

The Constituent Assembly of India sat for the first time on December 9, 1946, focusing on deliberations on specific features or segments which led to the adoption of the Constitution and a democratic republic. The intention of the constitution-makers can be inferred by the Judiciary’s integral role as a protector of the constitutional values, to undo the harm done by the legislature and the executive. In this article, I would try to highlight the Fourth and Fifth Constitutional Amendments. The rule of law is the bedrock of democracy and is the basic feature of the constitution, which cannot be altered or amended. It is the role of judicial review, to ensure that democracy is inclusive and that there is accountability since India opted for a parliamentary form of democracy, where every section is involved in policy-making and decision-making. The concept of accountability in any republican democracy while exercising public power has to be taken into consideration, irrespective of the extra expressed expositions in the constitution. Therefore, the aim of such emerging constitutional deliberations in India should be to ensure equitable and participative development which is the need of the hour in Indian social-economic-political milieu.

The Fourth Constitutional Amendment Act, 1955

The statement of objects and reasons of the bill aimed to amend Articles 31, 31A and 305 and Ninth Schedule of the Constitution of India.

The landmark decisions of the Supreme Court of India gave a wide meaning to clauses (1) and (2) of Article 31. The deprivation of property in the clause (1) was to be inferred in the widest sense, in order to be valid according to the decisions; provision for compensation under clause (2) of the Article was the intention. Therefore, to re-state the State’s power of compulsory acquisition and requisitioning of private property and distinguish it from cases where the operation of regulatory or prohibitory laws of the State results in “deprivation of property”, it was considered as a necessary step.

The laws which came in as social welfare legislation were taken into consideration to analyse their constitutionality with respect to the Articles 14, 19 and 31 and the Articles 31A and 31B and the Ninth Schedule were enacted by the Constitution (First Amendment) Act. Another proposal was to include in the Ninth Schedule to the Constitution two more State Acts and four Central Acts which fall within the scope of the sub-clauses (d) and (f) of the clause (1) of the revised article 31A.

In Saghir Ahmed v. State of Uttar Pradesh[1], the Supreme Court considered the issue of “whether an Act providing for a State monopoly in a particular trade or business conflicts with the freedom of trade and commerce guaranteed by Article 301”, but left the question undecided. Thus, another proposal was to bring clarity to Article 301.

The History behind Article 31A

In Kameshwar Singh v State of Bihar[2], the Bihar Land Reforms Act, 1950 was held invalid under the Article 14 for it classified the zamindars in a discriminatory manner for the purpose of compensation. The Central Government added into the Constitution, a new provision – Article 31A providing for the acquisition by the state of any estate or of any rights therein, or for the extinguishing or modifying any such rights, no law would be void on the ground of any inconsistency with any of the fundamental rights contained in the Articles 14, 19 and 31.

Article 31 was the only Constitutional Provision providing for compensation. The only exception was that such law should receive the assent of the President. The second proviso to Article 31A (1) refers to the ceiling limits. In the case of Bhagat Ram v State of Punjab[3], the object of this proviso was taken into consideration, it was stated that “a person who is cultivating land personally and it is his source of livelihood, should not be deprived of that land under nay law protected by Article 31A unless the compensation at market rate is given”.

The Constitutionality of Article 31A

In Ambika Mishra v State of Uttar Pradesh[4], the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the clause (a) of the Article 31A (1) on the test of the basic structure. In Minerva Mills v Union of India[5], the Court held that the whole of Article 31A is unassailable on the basis of stare decisis, a quietus that should not allow being disturbed. In Waman Rao[6] and I R Coelho[7], the First Amendment in which the Article 31A was introduced and Fourth Amendment which substituted new clauses to this Article have been held constitutional.

The Section 3 of the Constitution (Fourth Amendment) Act, 1955 which substituted a new clause (1), sub-clauses (a) to (e) for the original clause (1) with retrospective effect, do not violate any of the basic or essential features of the Constitution or its basic structure and was held valid and constitutional within the constituent power of the Parliament of India under the Constitution.

Various other objectives of the Act were:

With respect to the land reform, to fix limits to the extent of agricultural land that may be owned or occupied by any person, the disposal of any land held in excess of the prescribed maximum and the further modification of the rights of the landowners and the tenants in the agricultural holdings.

With respect to the proper plan urban and the rural areas for the beneficial utilisation of the vacant and the wastelands and the clearance of the slum areas.

In the public interest, to take over a commercial or industrial undertaking or other property, in order to secure the better management of the undertaking or property.

The Fifth Constitutional Amendment Act, 1955

It amended Article 3 of the Indian Constitution which provides the Parliament to effect, by law, reorganisation inter se of the states constituting the Indian Union. The Parliament is empowered to enact a law to reorganise the existing states by establishing new states out of the territories of the existing states, by uniting two or more states or parts of states, by uniting any territory to a part of any state, by altering their boundaries; or by separating territory from, increasing or diminishing the area of, or by changing the name of, a state.[8]

The History behind the Amendment

When Article 3 was drafted, the Princely States were not fully integrated and there existed the possibility of reorganisation of states on linguistic basis. Thus, the Constituent Assembly had foreseen that such reorganisation could not be postponed for long.

It did not lay down a time-limit within which the states concerned were to express their views, which could cause delay or even bring the parliamentary legislation to a standstill. The government of India wanted the reorganisation of the states on a linguistic basis which was hampered by the non-expression for any length of time.

Click Above

The Amending Act provided for the President to set a time-limit through which the Parliament could proceed with the matter without waiting for the views of the state concerned. Thus, made the proceedings regarding the reorganisation of states efficient and this propelled the states to check on the issues related to them responsibly. After the amendment, the procedure was changed and the exercise of this power by the Parliament was subject to the following two conditions:

A Bill for any such purpose cannot be introduced in the Parliament except on the recommendation of the President and

If the Bill affects the area, name or boundaries of a State, then before recommending its consideration to the Parliament, the President has to refer the same to the State Legislature concerned.

The Post Amendment Changes

Andhra Pradesh was the first state to be reorganized after independence wherein it was separated from the erstwhile Madras Province. The formation of Andhra Pradesh was one such example of the reorganization which became a reason for the amendment to the said article.

Article 3 provided the State Legislature and the Parliament with the authority to pass the bill of the reorganisation. The purpose was to give an opportunity to the concerned State Legislature to express its views on the proposals contained in the bill.

After the amendment, a lot of confusion surfaced regarding the meaning of the terms “express view of the State Legislature” resulting in a blatant violation of the Article 3 and in a drastic increase in the number of cases. The confusion was finally put to rest by the Apex Court in Babulal Parate v. The State of Bombay[9], when the State Reorganization Bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha. Some of its clauses, precisely Clause 8, 9 and 10, contained a proposal for the formation of the three separate units, namely,

Union Territory of Bombay;

State of Maharashtra including Marathwada and Vidharbha and

State of Gujarat including Saurashtra and Cutch.

The Bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha on the recommendation of the President as required by the proviso to Article 3 of the Constitution. This was then referred to the Joint Select Committee of both the houses which made its report dated July 16, 1956. In furtherance of the Report, some parts of the Bill were amended by the Parliament. On being passed by both the houses, it received the President’s assent and came to be known as the State Reorganisation Act, 1956. Instead of the three separate units, a composite state of Bombay was constituted under Section 8(1) of the Act.

Hence, there is no violation of Article 3 of the Constitution and the Act or any of its provisions are not invalid on that ground.

Conclusion

To conclude it all, the fourth and fifth constitutional amendment came to be a help and has played an effective and efficient role in reorganising the states as per the need. Henceforth, the amendment which brought in the clauses relating to the time limit helped in persuading the state governments as well as the Parliament to seek their attention in the matters related to the state reorganisation.

Bibliography

Case Laws

Ambika Mishra v. State of Uttar Pradesh, I.R. 1980 S.C. 1762 (India).

Babulal Parate v. The State of Bombay, 1960 A.I.R. 51 (India).

Bhagat Ram v. the State of Punjab, I.R. 1970 PH 9 (India).

I R Coelho v. State of Tamil Nadu, (1981) 2 S.C.C. 362 (India).

Kameshwar Singh v. the State of Bihar, I.R. 1953 Pat 167 (India).

Minerva Mills v. Union of India, I.R. 1980 S.C. 1789 (India).

Saghir Ahmed v. State of Uttar Pradesh, 1954 A.I.R. 728 (India).

Waman Rao v. Union of India, (1981) 2 S.C.C 362 (India).

Secondary Sources

Bakshi P.M., The Constitution of India, Universal Law Publishing Co.

Basu D.D., Commentary on the Constitution of India, 8th edn 2008, Vol. 3 Lexis Nexis Buttorworths Wadhwa Nagpur.

Jain M.P., Indian Constitutional Law, 5th edition, 2008, Lexis Nexis, Buttorworths Wadhwa Nagpur.

Seervai, H.M. Constitutional Law of India, A critical Commentary, 4th edn. Universal Law Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.

Shukla V.N., Constitution of India, 10 edn., 2001, Eastern Book Co.

Online Sources

https://ift.tt/2oL0YGR

https://ift.tt/35Ccepz

https://ift.tt/35wJRZQ (Last visited on 03-07-2019).

https://ift.tt/35GtkCz

Vyshnavi Neelakantapillai, “Right to Property under the Indian Constitution” available at https://ift.tt/32kRwIO (Last visited on 03-07-2019).

Endnotes

[1] 1954 AIR 728.

[2] AIR 1953 Pat 167.

[3] AIR 1970 P H 9.

[4] AIR 1980 SC 1762.

[5] AIR 1980 SC 1789.

[6] (1981) 2 SCC 362.

[7] (1981) 2 SCC 362.

[8] M P JAIN, Indian Constitutional Law 8 (Justice Jasti Chelameswar, Justice Dama Seshadri Naidu, 2018).

[9] 1960 AIR 51.

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skill.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

https://t.me/joinchat/J_0YrBa4IBSHdpuTfQO_sA

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

The post Fourth and Fifth Amendment Act, 1955 appeared first on iPleaders.

Fourth and Fifth Amendment Act, 1955 published first on https://namechangers.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Photo

One of the tallest leaders of India's freedom movement, Sucheta Kriplani was a member of the Constituent Assembly of India - the legislative body that drafted India's Constitution. She also went on to become the first woman Chief Minister of the Indian Republic, running the state of Uttar Pradesh (then United Provinces), the largest state in India. One of the most well known moments of parliamentary brilliance is from 14th August 1947, when right before Jawaharlal Nehru's 'Tryst with Destiny' speech, Kriplani led the Assembly into singing Vande Mataram, Saare Jahan Se Acha, and the Indian National Anthem. On her 112th Birth Anniversary, we honour this leading exemplar of patriotism and academic brilliance with this quote from her book. In this quote from 'An Unfinished Biography', Kriplani talks about how she felt unfulfilled until she joined politics to win freedom for her country. #indianpolity #india #feminist #feminism #womanempowerment #history #indianhistory #indianpolitics #british #britishraj #imperial #freedom #independenceday #independentindia #nehru #vandematram https://www.instagram.com/p/BzIoklIH0V1/?igshid=15puw1fiia7nj

#indianpolity#india#feminist#feminism#womanempowerment#history#indianhistory#indianpolitics#british#britishraj#imperial#freedom#independenceday#independentindia#nehru#vandematram

0 notes

Text

Can Sonia Gandhi Make The Congress Win In Lok Sabha Election 2019?

For sure, during the last two decades, Sonia Gandhi has been a potent force in Indian politics. Since the late-1990s when she took over the command of Indian National Congress (INC or Congress), Gandhi has invited both admiration and controversy in different time frames and situations. When Congress-led UPA came to power in 2004, there was much speculation about her becoming the Prime Minister. The nation was divided on whether she could occupy the country's highest post as she is not a natural citizen of India. As the issue was gathering steam, Sonia decided to relinquish the prospective PM-ship and appointed the renowned economist and former Finance Minister Manmohan Singh to lead the Indian government and country. Sonia was admired by her supporters as her decision of giving up the PM-ship was seen as an act of supreme sacrifice, which has very few parallels in the political history of modern India.

On the other hand, Sonia and her son Rahul Gandhi were much blamed for the poor performance of Congress in the 2014 election when the party reached its lowest ever tally since the birth of modern Indian democracy.

Gandhi's active participation in politics began to reduce during the latter half of the UPA government's second term owing to health concerns. She stepped down as the Congress president in December 2017 but continues to lead the party's Parliamentary committee. Although she never held any public office in the government of India, Gandhi has been widely described as one of the most powerful politicians in the country and is often listed among the most powerful women in the world.

Now, as 2019 Lok Sabha election is approaching, there is much speculation about the outcome of this election. There are many people who have pinned their hopes on Sonia Gandhi and her family, believing that Congress may once again regain its lost ground and emerge stronger. Well, there is a lot of speculation about the outcome of the upcoming election. Ganesha has analysed the scenario using the science of Astrology. Read on to know the findings:

Sonia Gandhi Election Details:

Political Party: Indian National Congress (INC or Congress)

Constituency: Raebarely, Uttar Pradesh, India

Date of Election: 6th May 2019

Sonia Gandhi Birth Details:

Date of Birth: 9th December 1946

Birth Time: 9:30 pm (21:30) (Unconfirmed)

Place of Birth: Lusiana, Italy

Astrological Alignment

Ganesha notes that malefic Rahu and Ketu are transiting adversely over natal Moon and Mars respectively. Besides, malefic Saturn is also aspecting her natal Moon. Moreover, she is passing through Ketu Mahadasha which is another adverse sign as per Sonia Gandhi election prediction.

Sonia May Find It Tough

Viewing all the planetary influences, Ganesha feels that Sonia Gandhi will have to work harder to achieve greater success in the upcoming election. She is likely to keep her traditional voters intact. However, due to BJP’s heightened popularity, she may not be able to add on to her votes. Thus, Congress’ performance may not be up to the mark even in the upcoming election. Do you want to boost your career prospects? Buy the 2019 Career Report.

Conclusion

Ganesha believes that Sonia Gandhi will secure her Lok Sabha seat Raebareli and will also strengthen the prospects of her party as seen in Sonia Gandhi horoscope prediction 2019. However, she will have to work very hard even for a small improvement in Congress’ tally. Ganesha foresees a situation which is far from a cakewalk for Congress and Sonia Gandhi.

With Ganesha's Grace,

Acharya Bhattacharya

The GaneshaSpeaks.com Team

#_revsp:GaneshaSpeaks#_lmsid:a0770000005BH3vAAG#astrology#_uuid:f87dced8-942d-3776-aeba-0c0edcd2af3e#_category:yct:001000606#_author:GaneshaSpeaks.com

0 notes

Text

Notification for first phase of Lok Sabha polls issued

NEW DELHI: Notification for the first phase of the Lok Sabha elections was issued on Monday, setting in motion the high-voltage electoral battle where the BJP seeks to return to power amid opposition’s efforts to present a united fight to unseat it.

Polling would be held in 91 parliamentary constituencies spread across 20 states on April 11 under the first of the seven-phase general elections.

The Election Commission Monday issued a notification signed by President Ram Nath Kovind for the first phase of the election.

With the issuance of the notification, the nomination process has begun which would continue till March 25. Scrutiny of the nomination papers will be held on March 26 and the last days of withdrawing nominations is March 28.

By the evening of March 28, a clear picture on the number of candidates in each of the 91 constituencies will emerge.

All parliamentary constituencies in 10 states and Union Territories will go for polling in the first phase.

These include, Andhra Pradesh (25 seats), Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya (two seats each), Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Andaman and Nicobar and Lakshadweep (one seat each), Telangana (17 seats) and Uttarakhand (five seats).

Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal will see polling in all the seven phases.

In the first phase, eight west UP constituencies, two in West Bengal and four in Bihar will go for polls. UP has 80 seats, while West Bengal and Bihar have 42 and 40 Lok Sabha seats respectively.

The Jammu and Baramulla seats in Jammu and Kashmir will also go for polling in the first phase.

The election will pit the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance against mostly different opposition groupings in various states, including of Congress, the Left and regional forces who are continuing to work out a grand alliance to minimise a division of votes against the saffron party.

The BJP has worked out a seat-sharing formula with some new allies and several old partners, by even making concessions in states such as Bihar. However, opposition parties are yet to do so in several states.

While the NDA hopes to make history by coming back to power for a second full term, the Opposition wants to unseat the Modi dispensation by raising questions on its performance on a host of issues, including economic growth, unemployment, corruption and social harmony.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee had led the NDA to back-to-back wins in 1998 and 1999 general elections but he was at the helm for only one full term.

The BJP, which lost three state polls last year, believes its Lok Sabha campaign is back on track following decisions such as 10 per cent quota for the general category poor, money transfer to farmers and a populist budget.

What has injected further confidence into the NDA fold is the fronting of the nationalist plank in the poll campaign after the Indian Air Force’s strikes on terrorist camps in Pakistan following the Pulwama terror attack in which 40 CRPF personnel were killed.

Modi has launched an aggressive campaign accusing the opposition of coming together for the sole purpose of removing him from power, when he is working to “remove poverty, corruption and terrorism”.

He had led the NDA to a sweeping victory in 2014 as it won 336 seats, reducing then incumbent Congress to its lowest total of 44 seats. (AGENCIES)

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

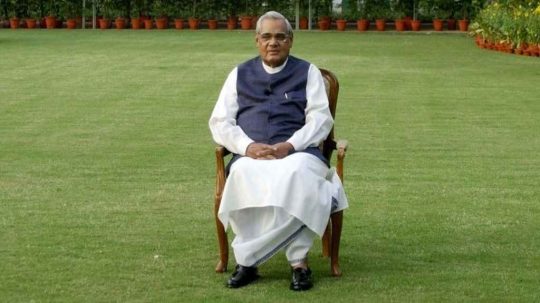

Atal Bihari Vajpayee Biography and Profile

New Post has been published on https://www.politicoscope.com/atal-bihari-vajpayee-biography-and-profile/

Atal Bihari Vajpayee Biography and Profile

Atal Bihari (Shri Vajpayee , Atal Bihari Vajpayee) was Prime Minister of India from May 16-31, 1996, and then again from March 19, 1998 to May 13, 2004. With his swearing-in as Prime Minister after the parliamentary election of October 1999, he became the first and only person since Jawaharlal Nehru to occupy the office of the Prime Minister of India through three successive Lok Sabhas. Shri Vajpayee was the first Prime Minister since Smt. Indira Gandhi to lead his party to victory in successive elections.

Born on December 25, 1924, in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh to Shri Krishna Bihari Vajpayee and Smt. Krishna Devi, Shri Vajpayee brings with him a long parliamentary experience spanning over four decades. He has been a Member of Parliament since 1957. He was elected to the 5th, 6th and 7th Lok Sabha and again to the 10th, 11th 12th and 13th Lok Sabha and to Rajya Sabha in 1962 and 1986. In 2004, he was to Parliament from Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh for the fifth time consecutively. He is the only parliamentarian elected from four different States at different times – UP, Gujarat, MP and Delhi. His legacy as Prime Minister is a rich one that is remembered and cherished even a decade after his term ended. It included the Pokhran nuclear tests, astute and wise economic policies that laid the foundations of the longest period of sustained growth in independent Indian history, massive infrastructure projects such as those related to development of national highways and the Golden Quadrilateral. Few Indian Prime Ministers have left such a dramatic impact on society.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee

Educated at Victoria College (now Laxmibai College), Gwalior and DAV College, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, Shri Vajpayee holds an M.A (Political Science) degree and has many literary, artistic and scientific accomplishments to his credit. He edited Rashtradharma (a Hindi monthly), Panchjanya (a Hindi weekly) and the dailies Swadesh and Veer Arjun. His published works include “Meri Sansadiya Yatra” (in four volumes), “Meri Ikkyavan Kavitayen”, “Sankalp Kaal”, “Shakti-se-Shanti”, “Four Decades in Parliament” (speeches in three volumes), 1957-95, “Lok Sabha Mein Atalji” (a collection of speeches); Mrityu Ya Hatya”, “Amar Balidan”, “Kaidi Kaviraj Ki Kundalian” (a collection of poems written in jail during Emergency); “New Dimensions of India’s Foreign Policy” (a collection of speeches delivered as External Affairs Minister during 1977-79); “Jan Sangh Aur Mussalman”; “Sansad Mein Teen Dashak” (Hindi) (speeches in Parliament, 1957-1992, three volumes); and “Amar Aag Hai” (a collection of poems, 1994).

Shri Vajpayee has participated in various social and cultural activities. He has been a Member of the National Integration Council since 1961. Some of his other associations include –

(i) President, All India Station Masters and Assistant Station Masters Association (1965-70);

(ii) Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay Smarak Samiti (1968-84);

(iii) Deen Dayal Dham, Farah, Mathura, U.P; and

(iv) Janmabhomi Smarak Samiti, 1969 onwards.

Founder-member of the erstwhile Jana Sangh (1951), President, Bharatiya Jana Sangh (1968-1973), leader of the Jana Sangh parliamentary party (1955-1977) and a founder-member of the Janata Party (1977-1980), Shri Vajpayee was President, BJP (1980-1986) and the leader of BJP parliamentary party during 1980-1984, 1986 and 1993-1996. He was Leader of the Opposition throughout the term of the 11th Lok Sabha. Earlier, he was India’s External Affairs Minister in the Morarji Desai Government from March 24, 1977 ,to July 28, 1979.

Widely respected within the country and abroad as a statesman of the genre of Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru, Shri Vajpayee’s 1998-99 stint as Prime Minister has been characterised as ‘one year of courage of conviction’. It was during this period that India entered a select group of nations following a series of successful nuclear tests at Pokhran in May 1998. The bus journey to Pakistan in February 1999 was widely acclaimed for starting a new era of negotiations to resolve the outstanding problems of the sub-continent. India’s honesty made an impact on the world community. Later, when this gesture of friendship turned out to be a betrayal of faith in Kargil, Shri Vajpayee was also hailed for his successful handling of the situation in repulsing back the intruders from the Indian soil.

It was during Shri Vajpayee’s 1998-99 tenure that despite a global recession, India achieved 5.8 per cent GDP growth, which was higher than the previous year. Higher agricultural production and increase in foreign exchange reserves during this period were indicative of a forward-looking economy responding to the needs of the people. “We must grow faster. We simply have no other alternative” has been Shri Vajpayee’s slogan focusing particularly on economic empowerment of the rural poor. The bold decisions taken by his Government for strengthening rural economy, building a strong infrastructure and revitalising human development programmes, fully demonstrated his Government’s commitment to a strong and self-reliant nation to meet the challenges of the next millennium to make India an economic power in the 21st century. Speaking from the ramparts of the Red Fort on the 52nd Independence Day, he had said, “I have a vision of India: an India free of hunger and fear, an India free of illiteracy and want.”

Shri Vajpayee has served on a number of important Committees of Parliament. He was Chairman, Committee on Government Assurances (1966-67); Chairman, Public Accounts Committee (1967-70); Member, General Purposes Committee (1986); Member, House Committee and Member, Business Advisory Committee, Rajya Sabha (1988-90); Chairman, Committee on Petitions, Rajya Sabha (1990-91); Chairman, Public Accounts Committee, Lok Sabha (1991-93); Chairman, Standing Committee on External Affairs (1993-96).

Shri Vajpayee participated in the freedom struggle and went to jail in 1942. He was detained during Emergency in 1975-77.

Widely travelled, Shri Vajpayee has been taking a keen interest in international affairs, uplift of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, women and child welfare. Some of his travels abroad include visits such as – Member, Parliamentary Goodwill Mission to East Africa, 1965; Parliamentary Delegation to Australia, 1967; European Parliament, 1983; Canada, 1987; Indian delegation to Commonwealth Parliamentary Association meetings held in Canada, 1966 and 1994, Zambia, 1980, Isle of Man 1984, Indian delegation to Inter-Parliamentary Union Conference, Japan, 1974; Sri Lanka, 1975; Switzerland, 1984; Indian Delegation to the UN General Assembly, 1988, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993 and 1994; Leader, Indian Delegation to the Human Rights Commission Conference, Geneva, 1993.

Shri Vajpayee was conferred Padma Vibhushan in 1992 in recognition of his services to the nation. He was also conferred the Lokmanya Tilak Puruskar and the Bharat Ratna Pt. Govind Ballabh Pant Award for the Best Parliamentarian, both in 1994. Earlier, the Kanpur University honoured him with an Honorary Doctorate of Philosophy in 1993.

Well known and respected for his love for poetry and as an eloquent speaker, Shri Vajpayee is known to be a voracious reader. He is fond of Indian music and dance.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee

POSITIONS HELD

1951 – Founder-Member, Bharatiya Jana Sangh (B.J.S)

1957 – Elected to 2nd Lok Sabha

1957-77 – Leader, Bharatiya Jana Sangh Parliamentary Party

1962 – Member, Rajya Sabha

1966-67 – Chairman, Committee on Government Assurances

1967 – Re-elected to 4th Lok Sabha (2nd term)

1967-70 – Chairman, Public Accounts Committee

1968-73 – President, B.J.S.

1971 – Re-elected to 5th Lok Sabha (3rd term)

1977 – Re-elected to 6th Lok Sabha (4th term)

1977-79 – Union Cabinet Minister, External Affairs

1977-80 – Founder – Member, Janata Party

1980 – Re-elected to 7th Lok Sabha (5th term)

1980-86– President, Bharatiya Janata Party (B.J.P.)

1980-84, 1986 and 1993-96 – Leader, B.J.P. Parliamentary Party

1986 – Member, Rajya Sabha; Member, General Purposes Committee

1988-90 – Member, House Committee; Member, Business Advisory Committee

1990-91– Chairman, Committee on Petitions

1991- Re-elected to 10th Lok Sabha (6th term)

1991-93 – Chairman, Public Accounts Committee

1993-96 – Chairman, Committee on External Affairs; Leader of Opposition, Lok Sabha

1996 – Re-elected to 11th Lok Sabha (7th term)

16 May 1996 – 31 May 1996 – Prime Minister of India; Minister of External Affairs and also incharge of Ministries/Departments of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Civil Supplies, Consumer Affairs and Public Distribution, Coal, Commerce, Communications, Environment and Forests, Food Processing Industries, Human Resource Development, Labour, Mines, Non-Conventional Energy Sources, Personnel, Public Grievances and Pension, Petroleum and Natural Gas, Planning and Programme Implementation, Power, Railways, Rural Areas and Employment, Science and Technology, Steel, Surface Transport, Textiles, Water Resources, Atomic Energy, Electronics, Jammu & Kashmir Affairs, Ocean Development, Space and other subjects not allocated to any other Cabinet Minister

1996-97 – Leader of Opposition, Lok Sabha

1997-98 – Chairman, Committee on External Affairs

1998 – Re-elected to 12th Lok Sabha (8th term)

1998-99 – Prime Minister of India; Minister of External Affairs; and also incharge of Ministries/Department not specifically allocated to the charge of any Minister

1999- Re-elected to 13th Lok Sabha (9th term)

13 Oct.1999 to 13 May 2004- Prime Minister of India and also in charge of the Ministries/Departments not specifically allocated to the charge of any Minister

Atal Bihari Vajpayee Biography and Profile (BJP)

#Atal Bihari Vajpayee#Atal Bihari Vajpayee Biography and Profile#Atal Vajpayee#Biography and Profile#India#Indian#Shri Vajpayee

0 notes

Text

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS ON AGRARIAN REFORM LEGISLATION

INTRODUCTION

The Supreme Court of India has, in the fifty years since the commencement of the Constitution, made a significant contribution in interpreting constitutional provisions on the right to property, directive principles of state policy and the legislation on agrarian reforms keeping in view an inarticulate premise of land to the tiller. The Indian agrarian reform programme is older than the Constitution. ‘Land to the tiller’ was part of our freedom struggle. The Congress Agrarian Reforms Committee had prepared a detailed programme on agrarian reforms. The aim was to free the agrarian system from exploitative elements. The Permanent Settlement introduced by Lord Cornwallis in 1793 in the then territories of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and subsequently extended to other areas needed to be annulled. All intermediary interests in estates between the actual cultivator and the State needed to be terminated. In the new agrarian structure envisaged by the committee, the cultivators would hold land directly under the State and would pay a fixed sum as land revenue. Tenants under private landlords would enjoy security of tenure and fixity of rent.

HISTORY OF AGRARIAN REFORM

In provinces where the Congress party had come to power under the Government of India Act, 1935, legislation on zamindari, talukdari, malgujari, jagirdari, and other intermediary tenures had been introduced. The Act did not contain guarantee of fundamental rights.

The demand made by the All Parties Conference at Lucknow for inclusion of fundamental rights in the new Constitution was rejected by the Simon Commission. The Joint Parliamentary Committee on the Government of India Bill, 1935 had rejected the idea, but felt it necessary to make a suitable provision in the Act of 1935 for protecting the interests of zamindars and other intermediary tenure holders. The protection was contained in sections 299 and 300 of the Government of India Act, 1935. Thus when the provinces introduced legislation for abolition of zamindaris, etc. they had to comply with the requirements of these sections. The inter-pretation of these provisions by the Federal Court and the Privy Council was there to support the view that the provincial legislatures by enacting suitable legislation were competent to annul the Permanent Settlement Regulations of 1793. The Constituent Assembly while drafting a suitable provision on the protection of right to property as a fundamental right was aware of the working of sections 299 and 300 of the Government of India Act, 1935 and their interpretation by the Federal Court and the Privy Council in cases concerning legislation on land tenures.

Thus after a prolonged debate and discussion it adopted the provision contained in these sections as right to property in article 31 of the Constitution. But the makers of the Constitution made special provision in clauses (4) and (6) of article 31 to protect legislation on agrarian reforms that was either pending before the provincial legislative assemblies or was on the anvil.

Soon after the Constitution come into force, the erstwhile zamindars where zamindaris had been abolished filed writ petitions in various high courts. The High Court of Allahabad upheld the validity of the Uttar Pradesh Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act, 1950. Likewise, the High Court of Nagpur upheld the validity of the Madhya Pradesh Abolition of Proprietary Rights (Estates, Mahals, Alienated Lands) Act, 1950.8 But the High Court of Patna declared the Bihar Land Reforms Act, 1950 as unconstitutional for it violated of article 14, the principle prescribed for payment of compensation to erstwhile zamindars had classified them in separate classes based on their annual net income. This judgement was rendered on 12 March 1951. 9 This provoked a prompt reaction from the government. It was decided to amend the Constitution so as to protect agrarian reform legislation beyond challenge.

Introducing the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill, 1951, B.R. Ambedkar, the then Union Law Minister stated in the Statement of Objects and Reasons: The validity of agrarian reform measures passed by the State legislatures in the last three years has, in spite of the provisions of clauses (4) and (6) of article 31, formed the subject matter of dilatory litigation, as a result of which the implementation of these important measures, affecting large numbers of people has been held up. The main objects of this bill are to insert provisions fully securing the constitutional validity of Zamindari abolition laws in general and certain specified Acts in particular. The bill when passed by Parliament became the Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951. It came into force with retrospective effect from the date of commencement of the Constitution. The amendment inserted articles 31A and 3IB and the Ninth Schedule to the Constitution. Article 31A was in the nature of an exception to article 31. Acquisition by the State of rights in estate shall not be deemed to be void on the ground of being inconsistent with any of the provisions of Part III. The expressions ‘estate’ and ‘rights in relation to an estate’ were also defined therein. Article 3IB provided for validation of Acts and Regulations included in the Ninth Schedule notwithstanding any judgement, decree or order of any court or tribunal to the contrary. The Ninth Schedule at that time contained a list of thirteen enactments. The Bihar Land Reforms Act, 1950 was included at serial number one in this list. The constitutional validity of the (First Amendment) was challenged in the Supreme Court on various grounds. A Constitution bench by a unanimous judgement and order dated 5 October 1951 upheld the validity of the impugned Act.12 Two broad propositions laid down in this judgement may be noted. The court held that an amendment of the Constitution under article 368 is not law within the meaning of article 13 and as such the prohibition in article 13(2) does not apply to an amendment which takes away or abridges a fundamental right. Accordingly, the abridgement of article 31 by newly inserted articles 31A and 3IB was upheld as valid. The court also held that the provision made in articles 31A and 3IB did not directly affect the jurisdiction of High Court and the Supreme Court and as such ratification of the impugned amendment by not less than one half of the states was not required. This shows the court’s anxiety to protect agrarian reform legislation against technical hurdles created by a narrow pedantic view of a constitutional provision.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS ON AGRARIAN REFORM LEGISLATION

The programme of land reforms was one of the major considerations in the schemes of social and economic restructuring of Indian society. The constitution provides fundamental rights (Part-Ill) and Directive Principals of state policy (Part-IV). The programme of agrarian reform was formulated to implement the directive of securing social and economic justice to those who worked on land.

The constitution of India has included the Land reform in State subjects. The Entry 18 of the State List is related to land and rights over the land. The state governments are given the power to enact laws over matters related to land.

The Entry 20 in the concurrent list also mandates the Central Government to fulfil its role in Social and Economic Planning. The Planning Commission was established for suggestion of measures for land reforms in the country. The specific articles of the constitution that pertain to land reforms are as follows:

Article 23 under fundamental rights abolished Begar or forced unpaid labour in India.

Article 38 contains the directive to the state that “State shall strive to promote the welfare of people by securing and promoting as effectively as possible. A social order in which justice, social, economic and political shall reform the institution of national life. And that it shall in particular, strive to minimize the inequalities in income”

Article 39 says that “the state shall direct it policies towards securing the ownership and control of material resources of the community and distributed them as best to sub serve the common good and at the same time ensuring the operation of the economic system not resulting in the concentration of wealth and means of productions to the common detriment”.

Article 48 directed the state to organize agriculture and animal husbandry on modern-scientific lines.

In the pursuance of these directives the land reforms laws aims at breaking the concentration of ownership of land by a few big land lords. The other articles are Articles 14, 19 (1) (f) and 31 and these are important as to the land reforms legislations.

Articles 14 “provide the state shall not deny to any person equality before law and equal protection of laws”.

Article 19 which guarantees to all citizens a number of freedoms, including in clauses (i) (f) the right to acquire, hold and dispose of property which has been deleted by the by forty fourth amendment Act 1978).

Article 31 guaranteed right to property and contained six clauses of which clauses (4) and (6) were particularly designed to protect land reforms legislations.

Article 31 as originally enacted was in the following terms:

(1) No person shall be deprived of his property saved by authority of law.

(2) No property movable or immovable, including any interest in, or in any company owning and commercial or industrial undertaking, shall be taken possession of or acquired for public purposes under any law authorizing the taking of such possession or such acquisition unless the law provides, for compensation for the property taken possession of acquired and either fixes the amount of the compensation or specified the principles on which and the manner in which, the compensation is to be determined and given.

(3) No such law as is referred to in clause (2) made by the legislation of a state shall have effect unless such law having been reserved for the consideration of the president has received his assent.

(4) If any bill pending at the commencement of the constitution in the legislature of the state has after it has been passed by such legislature been reserved for the consideration of the president and has received his assent then, with standing anything in this constitution the law so assented to shall not be called in question in any court on the ground that it contravene the provisions of clauses (2).

(5) Nothing in clause (2) shall affect (a) the provisions to any existing law other than a law to which the provisions of clauses

(6) Apply or (b) the provision of any law which the state may hereafter make:

(i) For the propose of imposing or leaving any tax or penalty

(ii) For promoting public health or prevention of danger to life. In pursuance if any agreement entered into between the Dominion of Indian and the Government of any other country or otherwise with respect to property declared by law to be evacuee property.

(6) Any law of a state enacted not more than eighteen months before the commencement of this constitution may within three months from such commencement be submitted to the president for his certification and thereupon, if the president by public notification so certifies it shall not be called in question in any court on the ground that it contravened the provisions of clause (2) of this article or has contravened the provisions of such sections (2) of the section 299 of the Government of India Act, 1935. The provisions made in clauses (4) and (6) provide inadequate to protect the land reforms laws.

CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT AND CASE LAWS

Hence the constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951 amended article 31 and added new Articles 31 A and .31 B and also added the Ninth schedule to the constitution listing 13 states-land reforms acts and providing that these acts would not be void merely on the ground that they infringed any of the Fundamental rights. The article 31 A, except from the operation of any of the safeguards conferred by the fundamental rights, law providing for acquisition of any “estate” or any right therein, but a state law making such provision required to be submitted to the president for his assent.

In Shankari Prasad v. Union of India[1] the constitutional validity of the first amendment was challenged. The Supreme Court upheld the Validity of the said amendment and in State of Bihar v. Kameshwar Singh[2] the Supreme Court observed that the land reforms legislation of Bihar was in conformity with Directive principles of state policy in order to achieve social justice. Article 31 A brought in by the constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951 was substituted by a more elaborate article by the constitution (Fourth Amendment) act 1955.

The new article had the effect of taking out the protection of the fundamental rights. All those legislation providing for and reforms measures, That is The acquisition by the State of any estate or of any rights therein or the extinguishment or modification of any such rights that is legislation aimed at the abolition of Jagirdars, Zaminadars and other feudal tenures.

By taking over the management of any property by the state for a limited period either in the public interest or in order to secure the proper management of the property, such law is not void because in consistent with or takes away rights of property.

The constitution (Seventeenth Amendment) Act, 1964 inserted a further provision laying down that where law made provision for the acquisition of an estate, and where any land comprised in such estate was held by anyone under personal cultivation, the law had to provide a ceiling limit acquisition could be effected only by payment of compensation not less in amount than the market value. It also amended the definition of the term “estate” to include land under Ryotwari settlement of as well as land held or let for purpose of agriculture of ancillary purposes. The expression land has not been defined. It was to be deducted with reference to the meaning attached to the term “estate”. The Supreme Court took a very liberal stand and proved itself as an active agent of social change. As the definition of an estate in the law relating to land tenures in the different local areas may differ, it is difficult to assign any meaning to the words “its local equivalent” when the estate itself has no fixed meaning.

In Karimbil v. State of Kerala[3] the Supreme Court made it clear that the definition of the term estate was not satisfactory. The provision in Article 31 A (1) (a) is not adequate to protect all measures of land reforms and further amendment of the provision called for. Hence, the Constitution (Seventh Amendment) Act, 1964 by which the definition of estate was further explained to include any land held under Ryotwari settlement. Any land held or let for the purpose of agriculture or for purposes any ancillary thereto, including waste land, forest land, land for posture or sites of buildings and other structure occupied cultivators of land agricultural labourers and village artisans.

None of the amendments to give effect to the aspects of land reform could deter the landlords from approaching the Supreme Court for questioning. The Constitutional validity of these constitutional amendments on legislative and technical grounds alleged that these are not adopted exactly in the Constitution in conformity with the procedure laid down in Article 368.

In Waman Rao v. Union of India[4] the validity of the Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951, which brought into being in the Constitution Article 31-A and 31-B and the Ninth Schedule was questioned. The Supreme Court declared that neither article 31-A and 31-B nor the Ninth Schedule destroyed or damaged the basic structure of the Constitution section 31-B in regarding the variation of certain acts and regulations.

None of the Acts, and regulations specified in the Ninth Schedule nor any of the provisions thereof shall be deemed to be void or ever to have become void on the ground that such Act, Regulation or provision is inconsistent with and takes away or abridges by any of the rights conferred by any provision of this part, and not withstanding any judgement, decree or order of any court or tribunal to the country each of the said Acts, and regulations shall, subject to the power of any competent legislature to repeal or amend it, continue in force.

The Constitution (Twenty-fifth Amendment) Act, 1971 had inserted a new Article 31 C which provided no law officiating social and economic reforms in the terms of Directive Principles contained in Article 39 (B) and (C) shall deem to be void for an alleged inconsistency with Fundamental Rights contained in Article 14, 19 & 31.

Writ petitions were also filed challenging the validity of the Mysore Land Reforms Act 1961 (as amended by Act, 14 of) 1965 which fixed the ceilings on the land holdings and conferred the ownership of surplus land on tenants. The above writ petitions along with some other in challenging petitions were heard by special bench consisting of eleven judges of the Supreme Court. In this case, though the amending Articles were held valid but on different reasoning by majority.

Subba Rao C.J. held that:

The power of the parliament to amend the Constitution is derived from Article 245 and 248 and not from Article 368 there of which only deals with procedure for amendment is a legislative process.

Amendment is law within the meaning of Article 13 of the Constitution and therefore if it takes away or abridges the rights conferred by the part III, it is void.

iii. On the application of the doctrine of prospective over ruling that our decision has prospective operation and therefore the said amendments will continue to be valid.

As the Constitution (Seventh Amendment) Act, holds the validity of the Punjab and Karnataka Land Reforms Act 1961, it cannot be questioned on the ground that they offend article 13, 14 or 31 of the constitution. After this decision the Constitution (Twenty Fourth Amendment) Act, 1971 was passed. In article 13 after the clause (3) a new clause (4) has been inserted stating. “Nothing in this Article shall apply to any amendment of the Constitution made under article 368”.

The Supreme Court manifested itself as an arm of social revolution and showed the need of protecting and preserving not only the land reforms measures against the challenges but also all the relevant amendments of the Constitution. Even though the first and seventeenth amendments were validated by the court by resorting to a novel doctrine of prospective overruling, by declaring that the said amendments and the law protected by them continued to be valid notwithstanding the abridgement of Fundamental Rights.

The Supreme Court contributed its due share in furthering the cause of agrarian reform. C.J. Subba Rao justified the need for protecting the amendments invalidated under the Golak Nath ruling primarily because of the concern for the land reform programmes and he observed that all these were done on the bases of the correctness of the decisions in Shakari Prasad’s case and Sajjan Singh’s case, namely that parliament had the power to amend the Fundamental Rights and the Acts, in regard to estates were outside judicial scrutiny on the ground that they infringed the said rights. The agrarian structure of our country has been revolutionized on the base of the said laws. The court held that the Fundamental Rights are outside the amendatory process if the amendments take away or abridge any of the rights and in Shankari Prasad’s and Sajjan Singh’s case conceded the power of the amendment over part III on an erroneous view of article 13 (2) and Article 368 and to that extent they were not good laws. The judgement proceeded on the following reasoning:

The Constitution incorporates an implied limitation that the fundamental Rights are out of the reach of the parliament.

Article 368 does not contain the power to amend it merely provides procedure for amending the Constitution.

The power to amend the Constitution should be found on the plenary legislative power of the parliament.

Amendments to the Constitution under article 368 or under other articles are made only by parliament by following the legislative process adopted by making in laws.

The contention that the power to amend is a sovereign power and that power is supreme to the legislative power, that does not permit any implied limitations and amendments made in exercise of that power involve political questions which are outside the scope of judicial review cannot be accepted.

The validity of the (Twenty Fourth Amendment) came up for discussion in Keshavanda Bharti v. State of Kerala.[5] Wherein a writ petition was field initially to challenge the validity of the Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963 as amended in 1969. The court held that the 24 amendment was valid and parliament had power to amend any or all the provisions of the constitution including those relating to the fundamental rights. And also the court held that power to amendment is subject to certain inherent limitations, and that parliament cannot amend these provisions of the constitution which affect the basic structure or framework of constitution.

The Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India[6] Supreme Court tested the directive principles as a whole with basic structure theory as propounded in Kesavananda Bharati Case. It is observed that “They (the Fundamental 73 Rights in part III and the Directive Principles of State Policy in Part IV) are like a twin formulas for achieving social revolution. The Indian Constitution is founded on the bedrock of the balance between Part III and Part IV and one should give absolute primacy to over the other is the harmony of the Constitution. This harmony and balance between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles is an essential feature of the basic structure of the Constitution. Those Rights are not an end to them but are means to an end. The end is specified in the Part III of the Constitution.

The Constitution (Forty Second Amendment) Act, 1976, Article 31- C was amended and its protection was extended to all the laws passed in the furtherance of any directive principles. All the Directive Principles were granted supremacy over the Fundamental Rights contained in Articles 14 & 19. Section 31-C says “No law giving effect to the policy of state towards securing all or any of the principles laid down in part IV shall be deemed to be void on the ground that it is inconsistent which takes away or abridges any of the rights conferred by Article -14 or article 19. That it is giving effect to such policy shall be called in question in any court on the ground that it does not give effect to such a policy. Now many Acts, passed by the parliament and the state legislature are constitutionally declared to be valid under Article 31 (b) although they may directly infringe the right to property. As a result of various amendments to the Constitution and by placing all land reforms laws in the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution, it has closed the door of challenging agrarian reform legislation in courts.

The Forty-fourth amendment made Right to property is no longer a fundamental right and article 300-A was added. The 44 Amendment removed the right to property from Part III of the chapter on Fundamental Rights by deleting article 19 (1) (f) and 31 and by inserting article 300-A. The reasons for 44″ amendment is as follows:

The special position sought to be given to fundamental rights, the right to property which has the occasion for more than one amendment of the constitution would cease to be a fundamental rights and become only a legal right. Necessary amendments for this purpose are being made to article 19 and article 31 is being deleted. It would be ensured that the removal of property from the list of fundamental rights would not affect the rights of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice.

Similarly, the right of persons holding land for personal cultivation and within the ceiling limit and to receive compensation at the market value would not be affected.