#Kings Island give us Phantom Theater again

Text

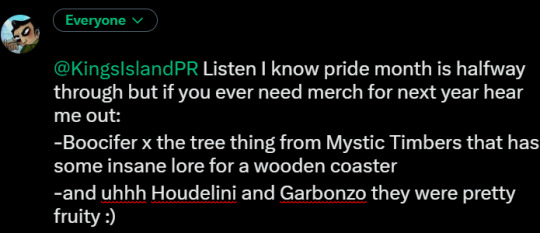

Nothing but bangers on my twitter

#this goes out to the 2 people that are fans of both rides#love Boocifer love Boo Blasters but (and huge chance ill never be able to go because of how far it is)#Kings Island give us Phantom Theater again#love Encore but I wanna see the ride#see the ghosts#and go nuts#Kings Island#Phantom Theater#Boo Blasters#:)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Alberto Savinio’s Pre-Postmodern Grotesque

Alberto Savinio, “Le songe d’Achille (The Song of Achilles)” (1929), private collection, Brescia, courtesy Galleria Tega, (c) 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS) / SIAE, Rome (all images courtesy the Center for Italian Modern Art)

I confess that it took a second trip to the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA), on the occasion of a conversation between Robert Storr and Lawrence Weschler on October 26th, to move past Alberto Savinio’s off-putting style and begin to see his paintings in formal, material terms.

Savinio, in tandem with Louise Bourgeois, is the subject of CIMA’s current exhibition, though he receives sole billing in the show’s title, Alberto Savinio. Bourgeois’ presence is explained on the Center’s website as part of its “practice of introducing work by contemporary artists into its exhibitions.” There are four Bourgeois sculptures and nine small (but historically significant) prints amid some two dozen works by Savinio.

Storr, who has written the recent, well-received book, Intimate Geometries: The Art and Life of Louise Bourgeois (Monacelli Press, 2016), is also the author of Philip Guston (Abbeville Press, 1991), which puts him in a particularly advantageous position, given Guston’s devotion to the work of Savinio’s older brother (by three years), Giorgio de Chirico, and by extension, of Savinio himself, to discuss the affinities between the two artists on display.

Savinio was an Italian artist born, like his brother, in Greece, whose life’s work falls into the tradition of the polymath, a line stretching from Leonardo da Vinci to Pier Paolo Pasolini. Starting off as a composer and pianist (whose wild, dissonant performances nearly destroyed the piano he was playing) and ending up primarily as a theater designer, he is best known for the unclassifiable, untranslatable, polyglot novel Hermaphrodito (1918). (It should be noted that de Chirico was also a prolific writer across a range of genres, from essays and treatises to poetry and novels, as well as autobiographical works under his own name and pseudonyms.)

‘Alberto Savinio’ was also a pseudonym, adopted by Andrea Francesco Alberto de Chirico in 1914 — the year in which Giorgio’s Metaphysical painting was reaching full flower in masterworks such as “The Song of Love,” now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York — in order to clear a professional path beyond the shadow of his famous brother.

Alberto Savinio, “Prometeo (Prometheus)” (1929), private collection, Courtesy Galleria Tega, Milan (c) 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS) / SIAE, Rome

The works in this show span a 10-year period, from 1926 to 1936 (there are also two lithographs from 1945 and ’46) and they answer the foremost question in my mind regarding Savinio’s multifarious activities, which is whether, in his forays into visual art, he was ultimately a dabbler. The exhibition proves that he was not; even when his canvases are jarring to the point of incoherence, he was serious, and he could paint.

In his relaxed and erudite conversation with Weschler, Storr matched Bourgeois (who, he said, hated to be called a Surrealist) and Savinio as kindred spirits residing on “the same archipelago of the grotesque.” He then delved into the derivation of ‘grotesque,’ which comes from the Renaissance-era excavations into the grotte, or caves, that lay to the northeast of the Circus Maximus in Rome, which were actually the buried rooms of the emperor Nero’s enormous Domus Aurea (House of Gold).

What astounded the artists and thinkers of the time — whose culture was based on the classical ideal, attesting to the perfectibility of humankind — was the discovery of Nero’s taste in, as Storr put it, artworks in which “the different orders — vegetable, mineral, human — are confounded.” This “deliberate mixing of codes” represented a form of aesthetic liberation, even if painters could explore it only in the border areas of their official work, never in the main picture. It would take another generation or two before such confounding of orders would become acceptable subject matter, as in the flamboyantly grotteschi paintings of Giuseppe Arcimboldo.

The grotesque is distinguished from dream imagery or expressionist distortion, Storr observed, by the insistent separation between states of being when they come into conflict, a condition in which “things clash [and] resolution is not possible.”

Dissonance is the sound of two or more notes not harmonizing, of tones stubbornly retaining their individual properties to the detriment of euphony. Savinio’s painting carries on the dissonance of his music (he called his style Sincerismo, or Sincerism), preserving the illusionistic character of Renaissance painting while dallying with various degrees of abstraction.

By contrast, his more Surrealistic work, which features animal/human hybrids and other anomalies, falls neatly in line with the Freud-besotted imaginings of Rene Magritte, Max Ernst, and others, thereby embedding itself within a stylistically consistent context, no matter how hard a painting like “Le réveil du Carpophage” (“The Awakening of the Carpophage,” 1930), with its musclebound nude male back and startled tiger’s head, is to look at.

Alberto Savinio, “L’abbandonnée (The Abandoned One)” (1929), private collection, courtesy Galleria Tega, Milan, (c) 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS) / SIAE, Rome

However, in such canvases as “Le fantôme de l’Opéra” (“The Phantom of the Opera,” 1929), “L’abbandonnée” (“The Abandoned One,” 1929), “Monumento ai giocattoli” (“Monument to Toys,” 1930), and “I re magi” (1929, which is translated on the wall label as “The Wise Men,” as in the Christmas story, but is literally “The Sorcerer Kings”), Savinio breaches the wall between realism and abstraction in a way that casts him, to quote Storr, as “everything a modernist should not be.” His abstract shapes, ensconced upon mountaintops, floating on the sea, or drifting across the sky, read as fully developed objects in illusionistic space and not, as the history of modernism would have you think, distillations of form.

This abuse of abstraction, so to speak, in its adulteration of old and new, became precedent-setting for the postmodernist revolt against the strictures of formalism. It also put Savinio on a collision course with the narrative of canonical modernism, of which his brother is a major player. (And on that note, it’s hard not to view the stacked objects of “Monument to Toys” as a sendup — if not an outright mockery — of de Chirico’s Metaphysical still lifes, perhaps taking direct aim at “Playthings of the Prince” from 1915, also at MoMA).

The two siblings were reportedly inseparable in their youth, later on not so much. In his own quirky way, Savinio ventured farther into abstraction than his brother did — de Chirico’s objects, while stripped to their essentials, are always identifiable — without making the leap from traditional tropes to an abstract conception of light and space.

De Chirico’s humanistic, Italianate take on Cubism, however, did exactly that, and to gaze into the crisp space and crystalline color of his greatest compositions is to scrub your vision clean, time and time again. Savinio muddies his approach by interjecting solidly rendered but unnamable geometric and biomorphic shapes into conventional illusionism. The resulting gestalt may be more resonant with the political and cultural corruption our time, but it also abandons the sublime — and the aspirations inherent in it. Rather than build something new, it makes do with the disorder we’ve inherited.

Bourgeois’ sculptures, made between 1984 and 2002, accentuate the contemporaneity of Savinio’s wayward modernism: a six-breasted, two-legged, headless bronze beast echoes Savinio’s animal/human hybrids (“Nature Study,” 1984, cast 1996); two wall reliefs conflate the bodily with the geometric, as spheres emerge from the surface to suggest eyeballs and breasts (“The Trauma Colors” and “He Murders My Eyes, both 1999); and a small, untitled head from 2002 made of red-striped fabric that is so perversely lifelike that it seems almost on the verge of speaking. This last piece, among the most riveting in the show, can be considered formally grotesque as laid out by Storr: it is simultaneously a convincing female head and a wrapped length of cloth. Neither the iconography nor the materials give ground to the other.

As I mentioned at the top of the review, my second visit revised my impressions of Savinio’s skills as a painter. His use of color is especially vibrant, and his textures (as in the studded surface of “The Phantom of the Opera”) are often inventive. While a number of the works on display seem to prefigure Neo-Expressionism, the remarkably tender “Ritratto di bambino” (“Portrait of a Child,” 1927), one of the most formally consistent and aesthetically pleasing pieces in the show, is embedded its own time, the back-to-basics Valori plastici movement, which was aligned with the culturally conservative “return to order” in the wake of World War I.

Alberto Savinio, “L’Île des Charmes (The Charmed Island)” (1928), Regole d’Ampezzo, Museo d’Arte Moderna “Mario Rimoldi,” Cortina d’Ampezzo, (c) 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS) / SIAE, Rome

If “Portrait of a Child” is perhaps the easiest of the works in the show to live with, “L’île des charmes” (“The Enchanted Island,” 1928), a large canvas commissioned for the Paris apartment of the art dealer Léonce Rosenberg, is by far the most impressive. (A companion painting made for the Rosenberg apartment will be added to the exhibition in January).

Its composition — an anti-hierarchical stack of volumetric shapes, several of which resemble tombstones — could serve as a template for Philip Guston’s ungainly piles of shoes, books, lightbulbs, and eyeballs. (It’s intriguing to speculate on whether Guston actually saw this work, but that possibility remains, to my knowledge, unprovable.)

While most of Savinio’s pictures, especially his Surrealist works, display relatively loose brushwork and frequent shifts in texture, “The Enchanted Island” is surprisingly precise and consistent. The naturalistic and abstract elements are linked via patterns of highlights that nail the solidity of the objects while tucking them into an invented, otherworldly space. Though dissonance remains between the geometric shapes and the landscape they inhabit, the artist’s coherent approach, like Bourgeois’ untitled fabric head, manages to avert the nervous tension we find elsewhere, and achieve a sense of balance that allows the viewer to revel unperturbed in the ravishing tonal arrays of yellow, blue, violet, orange, green, and gray.

In his novel Hermaphrodito, whose title evokes a gendered state once considered the irreconcilable combination of opposites, Savinio’s use of multilingual texts undermines any attempt by a single-language translation to preserve the spirit of the work — uncannily foreshadowing current debates about cultural identity, appropriation, and assimilation.

If many of the paintings in this exhibition remain visually fractious, with one style refusing to capitulate to another, the delicately knitted, moodily shimmering surface of “The Enchanted Island” suggests an integration of divisiveness that avoids both banality and Babel. Its ornate, almost cartoonish forms and undulating variations in tonality roil the imagery with a turbulence that stands in the opposite corner from de Chirico’s eternal silence. It exhibits no need to pursue the unitary or the universal, or to indulge in (to poach the title of another MoMA de Chirico) “The Nostalgia of the Infinite.” Its version of reality, its own and ours, is too recalcitrant for that.

Alberto Savinio continues at the Center for Italian Modern Art (421 Broome Street, Lower Manhattan) through June 23, 2018.

The post Alberto Savinio’s Pre-Postmodern Grotesque appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2ytLSJx

via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note