#Kirk Fordice

Text

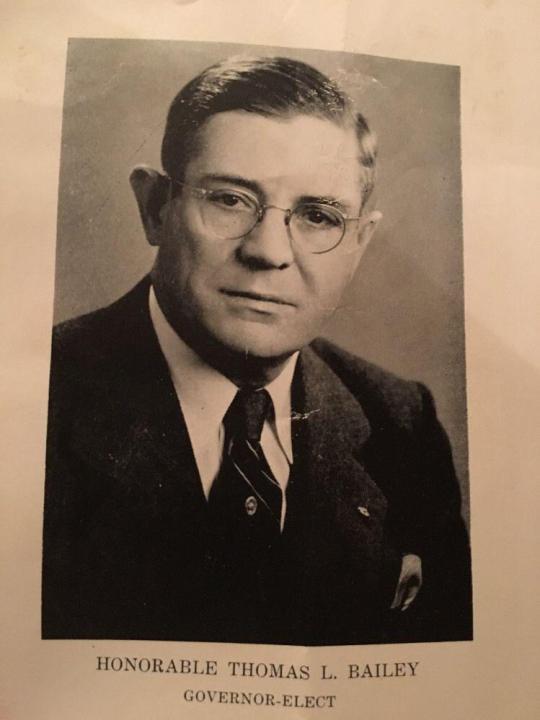

Mississippi Governor DILFs

Phil Bryant, Ross Barnett, Thomas Bailey, Paul B. Johnson Jr., Cliff Finch, Ronnie Musgrove, Fielding L. Wright, Wiliam Winter, James P. Coleman, Haley Barbour, Henry L. Whitfield, Hugh L. White, John Bell Williams, Kirk Fordice, Ray Mabus, Tate Reeves, Paul B. Johnson Sr., William Allain, Bill Waller

#Phil Bryant#Ross Barnett#Thomas Bailey#Paul B. Johnson Jr.#Cliff Finch#Ronnie Musgrove#Fielding L. Wright#Wiliam Winter#James P. Coleman#Haley Barbour#Henry L. Whitfield#Hugh L. White#John Bell Williams#Kirk Fordice#Ray Mabus#Tate Reeves#Paul B. Johnson Sr.#William Allain#Bill Waller#GovernorDILFs

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Process for filling board vacancies is gray area or black hole for state government

Process for filling board vacancies is gray area or black hole for state government

In 1996, former Gov. Kirk Fordice said the debate over whether to confirm the four white males he appointed to the Mississippi college board should …Process for filling board vacancies is gray area or black hole for state government

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Voces de Dios y Patria: Kirk Fordice

Voces de Dios y Patria: Kirk Fordice

Kirk Fordice (1934-2004), como gobernador de Mississippi, afirmó en noviembre de 1992 que:

América es una nación cristiana.

Como se cita en The New York Times, 18 de noviembre de 1992, el gobernador Kirk Fordice iluminó:

Cuanto menos enfatizamos la religión cristiana, más caemos en el abismo del carácter pobre y el caos en los Estados Unidos de América.

Voces de Dios y Patria:…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Attorney General candidate Andy Taggart media tour on the Coast

Attorney General candidate Andy Taggart media tour on the Coast

Andy Taggart announced his candidacy for Mississippi attorney general and kicked off his media tour on the Coast today.

Taggart will run against State Representative Mark Baker and Mississippi Treasurer Lynn Fitch in the Republican primary. Current Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood is stepping down to run for governor.

Taggart served as chief of staff for former Governor Kirk Fordice. He…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

“The less we emphasize the Christian religion the further we fall into the abyss of poor character and chaos in the United States of America.” ~Mississippi Governor Kirk Fordice, November 18, 1992

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Who is Cindy Hyde-Smith? 5 things to know about Cochran's Senate replacement

Visit Now - http://zeroviral.com/who-is-cindy-hyde-smith-5-things-to-know-about-cochrans-senate-replacement/

Who is Cindy Hyde-Smith? 5 things to know about Cochran's Senate replacement

AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis

(Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant appointed Cindy Hyde-Smith, the state’s agriculture commissioner, to the Senate to replace outgoing Sen. Thad Cochran. )

With Sen. Thad Cochran’s impending retirement, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant appointed Cindy Hyde-Smith to the seat.

Cochran, a Republican, announced earlier this year that he would resign April 1 due to health issues. According to state election laws, it’s up to Bryant to appoint a replacement until a special election is held in November.

Hyde-Smith has served as the state’s agriculture commissioner since 2011. She is expected to run in the special election to finish out Cochran’s term.

Read on for a look at Hyde-Smith and her career.

She will be the state’s first female U.S. senator

Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant congratulates Cindy Hyde-Smith after announcing her appointment to the U.S. Senate.

(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Hyde-Smith, 58, is the first female to represent Mississippi in Congress.

Her appointment leaves Vermont as the last state to not have a women in either the U.S. House of Representatives or Senate, according to data from Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics.

Hyde-Smith is a former Democratic state lawmaker

Prior to her election as commissioner of the state’s agriculture and commerce agency, Hyde-Smith served as a state senator for 12 years, from 2000 to 2012.

In the state Senate, Hyde-Smith served as chair of the agriculture committee. Though she was a Democrat, Hyde-Smith would often vote with Republicans, the Clarion Ledger reported. She switched to the Republican Party in 2010.

Her former party affiliation has left some Mississippi Republicans uneasy about her appointment, according to the newspaper.

Andy Taggart, a prominent Republican in the state, alluded to a possibility that Hyde-Smith could be vulnerable to a primary challenger, particularly Chris McDaniel, in November’s special election.

“In 1991, the entire GOP Establishment supported a recent party switcher and statewide office holder in the race for Governor. Instead, Kirk Fordice came roaring out of nowhere and won a three-way primary,” Taggart said on Twitter.

Hyde-Smith is a supporter of President Trump.

She’s been focused on the agriculture industry for a while

Hyde-Smith’s dedication to Mississippi’s agriculture industry started long before she became commissioner. As a state lawmaker, she “became known as a passionate advocate of farmers and ranchers” in the state, her commissioner biography said.

She championed efforts in the state Senate aimed at protecting the agriculture industry, including right-to-farm and property rights, according to her biography.

Hyde-Smith has also received numerous awards related to her work in the agriculture industry, according to her biography, including from the Mississippi Association of Conservation Districts and the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation.

Hyde-Smith and her husband raise beef cattle

Cindy Hyde-Smith (right) stands with her husband, Mike Smith (left) and daughter Anna-Michael Smith (center) as the governor announces her appointment to the U.S. Senate.

(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Along with her husband, Hyde-Smith raises beef cattle on their farm in Brookhaven, Mississippi, about 60 miles south of Jackson. They are also partners in Lincoln County Livestock, which holds cattle auctions.

Hyde-Smith grew up as a tom-boy, riding horses and farming, she told the Delta Business Journal in 2015.

“I loved working with the soil,” Hyde-Smith said. “And it taught me a deep appreciation for the farmer and farming. You grow your food, feed your family and farmers grow the food to feed America. That garden and that concept all those years ago really began my journey into agriculture. Farmers really do feed America.”

Two things made Hyde-Smith fall in love with her husband, she told the Business Journal: he could saddle a horse and he tithed, the act of giving 10 percent to the church.

She has one daughter, Anna-Michael.

She values “different perspectives”

Hyde-Smith told the Delta Business Journal that she had “a few concerns” when she decided to run for agriculture commissioner – especially as she was vying for a job that no woman had held before her.

“I wondered if Mississippi was ready for a female [agriculture commissioner],” she said. “When it came to agriculture; I couldn’t help but wonder if my being a woman would be an issue.”

But Hyde-Smith said she didn’t experience any problems and only a few people ever brought up the fact that she was the first woman in the position.

“There are so many issues that concern farmers that they need a voice, a strong voice, and it doesn’t matter whether that voice comes from a man or a woman, as long as it’s sincere,” Hyde-Smith said.

She told the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture (NASDA) that it’s important to include women in conversations because “it is imperative to have those with different perspectives and viewpoints involved in the discussion so that information from all sides and angels can be heard and considered.”

“Often, women tend to offer a unique perspective when it comes to establishing a vision for the future and vetting possible solutions,” she said. “In many instances, women tend to guide the human side of decision making and can patiently weigh all the circumstances.”

Kaitlyn Schallhorn is a Reporter for Fox News. Follow her on Twitter @K_Schallhorn.

0 notes

Link

Flags of the United States of America, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, and the state of Mississippi hang at the Chahta Enterprises Metal Fabrication plant.

It’s just before 5 p.m., and even though some of the lights have already been switched off, the electric hum from the large overhead fuorescents can still be heard as they slowly cool down. Even in the darkness, three flags can be seen hanging vertically from the rafters. In the center, the American fag. To its right, the state fag of Mississippi. To its left, the flag of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

This is no ordinary metal fabrication facility. Sure, sparks fy brightly as the intense heat from a welding torch makes contact with what will one day be part of an American-made flatbed trailer, an image that could just as easily be seen in industrial cities such as Detroit or Buffalo.

Here at the Chahta Enterprises Metal Fabrication Operation, however, the man behind the mask as sparks cascade around him is a Choctaw Indian. Twenty years ago, he might not have had the opportunity to hold a job like this. But here he is, part of a workforce more than 5,750 strong, all of them employed by the Mississippi Choctaw.

As the few remaining workers finish up on a bright orange trailer, another man emerges from behind a translucent yellow eye-shield. He’s tall and stocky and stands out even among the large machines that fill the room. He has dark skin and even darker, somewhat curly short black hair. His name is Mark Patrick, and he has been Director of Quality and Sales at Chahta Metal Works since the plant opened in 2014.

Patrick is quiet at first. Then I ask if he has any children. Patrick perks up a bit.

He tells me that he has two sons. One recently graduated from the University of Southern Mississippi, using the tribe’s generous college scholarship program to pay for his education. His other son works here at the plant.

Upon completion, a flatbed trailer gets a sticker that shows Chahta Enterprises Metal Fabrication worked on it.

In a sense, Patrick embodies the remarkable resurrection of the Mississippi Choctaw, a group that a century ago was nearly extinct and a little over three decades ago sufered in seemingly hopeless poverty. Today the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is one of Mississippi’s largest employers, one of the nation’s most successful Indian nations, a glittering example of what can happen when government loosens its hold and allows a tribe to run its own affairs. It is a miraculous transformation, one of the greatest minority success stories in American history.

But how? How is it that now, a Choctaw like Patrick is able to send one son to college and give the other son the opportunity to work and sustain himself when just over one generation ago most of the tribe was living in utter poverty, barely making $2,000 a year?

The Choctaw tradition of business can be traced back to the 18th century, back when the Choctaw people had a strong economy based on communal ownership and responsibility. At one time in the South, pidgin Choctaw was the language of commerce. The Choctaw favored business over warfare, the sharing of goods over the shooting of arrows.

Marveling at their affinity for trade, Robert White, author of Tribal Assets, wrote that the Choctaw “were the late 20th-century Japanese of the pre-European South.”

After a series of treaties gradually tore land away from the Choctaw beginning in 1786 with the Treaty of Hopewell, tribal members who were able to avoid Removal, the Choctaw’s preferred term for the “Trail of Tears,” made their living sharecropping.

“Made their living” is a bit of an exaggeration, as thousands of Choctaw sharecroppers were forced into bitter poverty and wretched lives. On its website, the tribe’s own economic development history quotes a congressional investigator’s description of the Mississippi Choctaw in the early 1900s as “the poorest pocket of poverty in the poorest state in the country.”

By 1910, the number of Choctaw in the state had dwindled to just 1,253. In 1918, one-fifth of the remaining population was killed in a flu epidemic. For years, the survivors barely existed in the poor red clay farmland of hill country Mississippi.

In 1945, this tattered remnant fnally won tribal recognition from the federal government. But it took more than federal acceptance for the tribe to emerge from its economic doldrums. During the 1950s, tribal leaders had seen little to no improvement in the desperate living conditions of their people, even with what help they were able to get from the forever financially strapped Bureau of Indian Affairs. Average annual income was $600 per family, with most lucky to make more than $2.50 a day on farm wages.

The tribe needed a savior. It found him in Phillip Martin, whose knack for economic development has since become legend to Native Americans across the land.

Martin started out on the Tribal Council but became chief in 1978. From the beginning, he was convinced that the tribe would never be successful depending on the federal government to save it. With 80 percent of the Choctaw unemployed, Martin knew what the tribe desperately needed most: jobs.

Franklin Taylor (white shirt) and Toby Steve process bed sheets and table cloths at the tribe’s busy commercial laundry.

In 1969, Martin led the tribe to seize upon the one opportunity he could see at the time, federally funded housing. The tribe launched Chahta Development, a construction company. Instead of letting the feds continue to pay contractors to build low-income housing on the reservation, the Choctaw got the feds to pay Chahta Development to build the houses.

The tribe didn’t just begin a construction company that day. It began an economic resurgence that would expand to provide almost 6,000 permanent, full-time jobs and a payroll of more than $100 million. The tribe became one of Mississippi’s major employers, with enough money to establish a scholarship program that pays for a Choctaw’s college education and gives students a stipend to live on as well as a laptop, ultimately preparing them to hold more specialized jobs.

In the two decades ending in 1999, household income on the reservation jumped from $2,500 to $24,000, while unemployment fell to about 2 percent. Between 1985 and 2000, life expectancy in the tribe rose 20 years. It’s only gotten better from there.

Talk to anyone on the reservation about how the tribe was able to pull it of and the conversation goes right back to Phillip Martin. He is revered much like a saint, a Moses fgure leading his people out of a wilderness of poverty and into the promised land of prosperity.

“He was a natural-born leader,” John Hendrix, the tribe’s economic development director, says about Martin as we sit in the conference room of Chahta Enterprises. We’re sitting in building A of the TechParc, a campus of multiple buildings that house Choctaw business and industry. Martin hired Hendrix in 1993 after he had acquired a business degree from Millsaps College. He got the job even though he is not a Choctaw, a regular occurrence at the time, considering more than half of their employees were not Native Americans.

“I think what got (Martin’s) spark was that he was stationed over in Europe after World War II,” Hendrix says. “So he saw Europe rebuild itself after the war, and he came back and said, ‘Well, we can do that, too.’ He wasn’t a micro-manager; he just intuitively knew what needed to be done and he hired the right people for the job.”

Unlike some bosses, Martin was always open to letting people work on new ideas that had potential to better the tribe.

“He had a very entrepreneurial approach to management, and he discouraged red tape and bureaucracy.

“If somebody had an idea, even if it wasn’t directly their job, Martin would let them try it,” Hendrix says. “And if it didn’t work, he didn’t fire them. He had a very flat management structure, and it worked.”

Martin’s Mississippi miracle was nothing less than a revolution. In time, it would inspire other tribes across America to subscribe to his self-help philosophy.

In a state that regularly ranks at the bottom in terms of per capita income, the scope of the Choctaw’s economic influence is impressive. The tribe has 12 businesses, ranging from Defense contracting to growing organic vegetables to commercial laundry services. They have a brand-new health center and three casinos that since the first one opened in 1994 have provided thousands of jobs.

Mark Patrick, behind the welder’s mask, finishing up work on a flatbed trailer.

Martin kicked it of with sheer force of personality. He coaxed the tribe into springing for an industrial park with no tenants in sight. Then he criss-crossed the country for years, buttonholing business executives and trying to sell them on moving to the reservation.

Finally, he lured a plant that hired Choctaws to install the spaghetti-like tangle of wiring in automobiles. He got American Greetings, a billion-dollar player in the lucrative greeting card industry, to move into a 120,000-square-foot plant on the reservation. He talked the neighboring town of Philadelphia into using municipal revenue bonds to help pay for it. He made the tribe a powerful lobbying force in Washington, D.C., where he was a familiar figure in the offices of senators, congressmen and federal agencies. And with that, the empire began to grow. So did the tribe’s reputation, which made it that much easier to recruit industry and key employees.

In 1988, Congress approved the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, which allowed tribes to get into the casino business. Indian gaming took America by storm.

The Choctaw met initial resistance from state government but in 1994, with the help of a new governor, Kirk Fordice, a towering hotel and casino complex rose from the red dirt on an otherwise unremarkable stretch of state highway in rural Neshoba County.

The Silver Star Hotel and Casino is an elaborate gambling palace with four restaurants, entertainment venues, first class hotel and a sea of slot machines and card games. If the Silver Star is not enough excitement, a covered walkway soars guests over the adjacent highway and into a sister casino and hotel complex, the Golden Moon, which opened in 2002. (A third, Bok Homa, is a two-hour drive from the frst two.) Along with two championship golf courses and a water park, they make up the multi-million-dollar Pearl River Resort, which quickly became the tribe’s major source of revenue. An economic impact statement prepared by Mississippi State University once estimated that the resort businesses generated more than $180 million in wages alone.

All of this has given the tribe the ability to take care of itself. And it does. But not, as some tribes do, by giving large annual payments to rank-and-file members. The latest semi-annual check the Choctaw sent to each member was a demure $500. The total annual payment is limited to $1,000 per member.

The day starts early at the greenhouses.

Instead, they do something much more valuable for fellow Choctaws. All that money from this self-made empire gets plowed back into programs and services that are the envy of poorer tribes — a 120-bed nursing home, subsidized housing, transportation, day care, Head Start, food programs for the elderly, programs for those struggling with substance abuse and addiction. If a tribal member needs a job or a house, the tribe can help. It is a business juggernaut and miniature Great Society rolled into one. And, most remarkably, the Choctaw were doing it even before casino gambling came along.

It’s a rainy St. Patrick’s Day in Tucker, not far from Choctaw, where the tribal government is headquartered. The Tucker Elementary School, one of eight reservation schools, is having its annual spring festival inside a gymnasium.

The program has “Halito!” written across the top in dark green. It means “hello” and is heard multiple times as Choctaw children in brightly-colored traditional garb begin to fill forest-green bleachers. Some of the girls’ dresses cost upward of $800. Some are homemade. Many conceal at least 40 safety pins, needed just to hold everything together.

The Choctaw also supply organic vegetables to commercial markets like Whole Foods as far away as Jackson.

The Choctaw Princess, Emily Shoemake, is here, almost at the end of her year-long term. The princess is beautiful, her dress covered in rose print, a crown atop her head and a hand-woven basket held in the crook of her left arm.

Shoemake almost wasn’t able to fulfll her duties as princess. As a mechanic in the 91 Bravo Humvee unit, she was supposed to go off to Army basic training a few weeks into her term. Current Chief Phyliss Anderson wrote a letter pleading her case, and the Army allowed her to report immediately after she finished her term.

The spring festival is meant to showcase the children and traditional Choctaw dances, as well as celebrate their culture. I look inside the program and see a few dances I recognize, like the “Snake Dance,” which mimics the slithering of a snake as dancers hold hands and weave in and out of an ever-changing line. As I scan further inside, I see a name I recognize:

“Invocation — Mark Patrick”

Sure enough, Mark Patrick emerges shortly after the start of the festival to say a prayer in Choctaw. The only words I recognize are “Jesus Christ” and “Amen.” He’s wearing a green shirt for St. Patrick’s Day.

“It’s my day, Patrick,” he jokes after walking over to where I’m leaning up against a padded gym wall.

Patrick is anything but quiet here. He’s a fxture in the Choctaw community. He knows everyone. Speaks to everyone. Waves at everyone. He spots a 14-year-old girl and asks how her driving test is coming along. He asks where her mother is and says he needs to talk to her.

Field Coordinator and Greenhouse Manager Daphne Snow with her precious cargo of fresh produce.

“What did I do?” the girl snaps back. She’s heard this question before.

I ask Patrick how he knows everyone so well, and he tells me he likes doing a lot of community outreach. When he grew up, he says, he had no idea who his father was. His grandmother raised him and wove baskets to support him.

“I just know everybody,” Patrick says. “A lot of the kids look for that father or mother figure or infuence in their lives, and it means a lot to me.”

Patrick watches as children perform the Raccoon Dance. “Some of these kids have no clue what they’re doing or why they’re out there,” he says. “But they’ll realize it soon enough.”

It’s true, and these children don’t know it yet, but the opportunities they have even at this age already outnumber what their parents and grandparents had. An older Choctaw teacher in a magenta zip-up jacket watches her class dance on the Dreamsicle-orange basketball court. She won’t reveal her name. She’s there to watch one of her last classes in 40-plus years of teaching school.

“I feel like I’m watching my grandkids out there now,” she says. “Things have changed so much.”

John Hendrix became the tribe’s director of economic development in 1993 after getting a business degree from Millsaps College.

When I ask how she’s seen the opportunities for children in her classes change over the years, she finally turns to look at me.

She says she’s seen countless children grow up without having a chance. She’s seen kids whose only job opportunities were spending their years behind the wheel of a school bus, kids used to having no hope of a better life.

Things are diferent now. The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians has more jobs than they do working-age Choctaw these days. Average income has risen, education has improved, anyone who needs a home gets one, an economic impact report once pegged the tribe’s contribution to the state GDP at around $1.2 billion, and the chances to succeed have never been higher.

The children dancing and laughing in the middle of this gym on a rainy St. Patrick’s Day are no longer just Choctaw kids. They’re comeback kids.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Ariel Cobbert, Mrudvi Bakshi, Taylor Bennett, Lana Ferguson, SECOND ROW: Tori Olker, Josie Slaughter, Kate Harris, Zoe McDonald, Anna McCollum,

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw and Choctaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at [email protected].

The post Unconquered and Unconquerable: The Resurrection of the Choctaw appeared first on HottyToddy.com.

0 notes

Photo

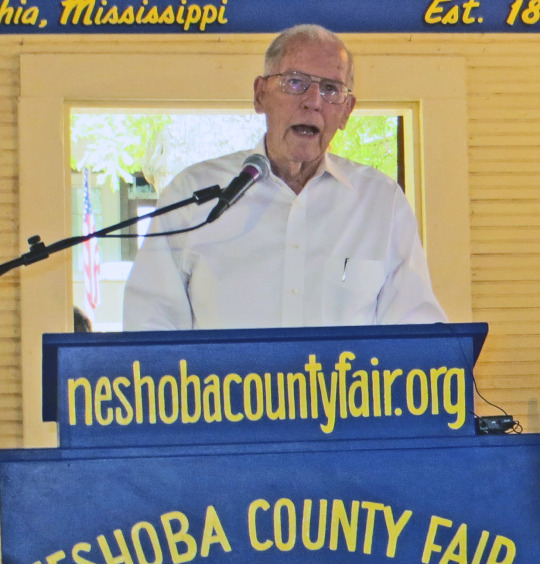

The late controversial Former Gov. Kirk Fordice (R) of The Great State of MS & I ( Nov/1998) We had a very nice talk and I had no idea that he was preparing for a Press Conference soon after that day to disclose he was battling prostate cancer which he beat. He died from leukemia in 2005. (at United States)

0 notes

Photo

January 27, 2017:

One week into his presidency, Donald Trump seems determined to maintain his stance on voter fraud. To do so, he refers to the one source upon which he’s based his claims.

According to his LinkedIn profile, Gregg Philips is currently chairman of AutoGov, Inc., a tool that helps users determine their Medicaid eligibility. He claims to have previously worked as Finance Director for both the Alabama Republican party and for “outspoken conservative” Kirk Fordice’s successful bid for Mississippi Governor in 1991. He then went on to serve as Executive Director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services and of the Mississippi Republican Party, the latter until November 1996. He is otherwise a private citizen who concerns himself with election integrity on a volunteer basis.

He is the founder of VoteStand, an app that purports to be “America’s first online election fraud reporting app [which] provides you with the tools and support you need to quickly report suspected election illegalities as they happen.” The app allows you to take a picture, fill out a form with specific identifying information, and submit it, all of which is geo-located “in order to provide enough evidence to pursue legal action against the person/persons committing the fraud.”

“Once the fraud is found,” the site continues, “you will be able to share your breaking story with the help of some of the biggest social networks around. Your picture may even make our top 10 wall.”

Nowhere does the website explain how many claims are received, how many result in prosecution, or how claims are verified at all.

Note also the dates of each of these tweets: the results Trump says he is “looking forward to” are over two months old.

#trump#voter fraud#gregg phillips#votestand#make america great again#alternative facts#illegal votes

0 notes

Text

Frank Melton

Frank Ervin Melton (March 19, 1949 – May 7, 2009) was the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, United States, from 4 July 2005 until his death on 7 May 2009. Melton, an African American, defeated the city's first black mayor Harvey Johnson, Jr. Melton won 63 percent of the vote in the Democratic primary against Johnson, who had served two terms. Melton quickly swept into action to rid Jackson of drug-related crime, improve economic development, and improve city infrastructure. Since Melton became mayor, he touted economic-development projects totaling over $1.6 billion, creating at least 4,500 jobs in the city. Others pointed out that many of those projects were in the works when he started in office. However he was embroiled in several controversies while being mayor, including questionable power breaches and criminal misdemeanor activity.

Early life

Melton was born in Houston, Texas on March 19, 1949, to his parents Herbert Melton and Marguerite Haynes-Melton, both of whom were active members of the University Presbyterian Church in Houston. Prior to graduation from high school and following in the grid-iron footsteps of one of his earlier Booker T. Washington Eagles quarterback idols, Eldridge Dickey (Tennessee State Univ., Oakland Raiders), Frank was a popular, studious, and disciplined Quarterback for the Eagles. Melton graduated from Booker T. Washington High School. He moved to Nacogdoches, Texas to earn a BA at Stephen F. Austin State University. In college, he took a position with the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, serving as Director of Recreation at its Lufkin State School.

Early career

He entered broadcasting after graduation, first as a Sports Anchor for KTRE TV in Lufkin, Texas and then, in 1977, as general manager of KLTV TV. He climbed the ranks at KLTV TV before becoming president of Buford Television, Inc. In 1984, he became Chairman and CEO of WLBT TV Inc, in Jackson, Mississippi, in which position he remained until 2002.

Melton served as the head of the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics for 14 months, appointed by former Mississippi Governor Ronnie Musgrove in December 2002. Governor Haley Barbour, who defeated Musgrove in the 2003 gubernatorial election, dismissed Melton and other holdover political appointees when he took office. Melton also served in numerous other fields, including serving as the director of the Governor's Criminal Justice Task Force, after being appointed by former Governor Kirk Fordice.

Melton served on the national board of directors for the Broadcast Music Incorporated (BMI), the Liberty Broadcasting Board of Directors, and the NBC Affiliates Board of Directors. He served on the Liberty Broadcasting board of directors; the Wave board of directors, the Community Broadcast Group, and the NBC Affiliates board of directors.

Community work

Melton also worked as a member of the board of directors for United Way and the Jackson Chamber of Commerce. He was an instructor at Jackson State University. He gave numerous speeches in the inner-city high schools and city universities.

As mayor

Melton led drug sweeps and drug raids. The city's narcotics unit was reduced and few drug arrests were made. Many citizens were pleased to see him take this hands-on and vocal approach to addressing the city's problems. Yet many city residents, including the NAACP and the ACLU, have disagreed with the mayor's crime-fighting tactics and what they call illegal and unconstitutional actions. He wore a Jackson Police Department badge and carried a gun.

In April 2006, Melton lambasted Hinds County District Attorney Faye Peterson because she would not put his star witness, Christopher Walker, on the stand to testify against Albert "Batman" Donelson, the alleged leader of the Wood Street Players. The district attorney had to drop Walker from the witness list because the defense provided affidavits showing that Walker had long lived with mayor. Melton had given Walker a copy of his credit card, a car, cash and other assistance. The mayor responded that he was offering Walker "witness protection."

Soon after Donelson was acquitted, Melton held a press conference with Walker, during which he accused the county's first black female district attorney of having an affair with a murdered bail bondsman, an allegation that was not substantiated. Within days of that press conference, federal investigators revoked Walker's probation because he had failed nearly a dozen drug tests during the period leading up to the Donelson trial.

After a series of articles and photographs appeared in spring 2006 showing that Melton was carrying concealed firearms without a permit, and amid increasing editorials calling for authorities to curtail Melton's actions, Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood investigated Melton's actions. On June 1 Hood sent Melton a letter warning of prosecution if he continued to carry weapons into places where they were prohibited, further warning him he was not a police officer. Melton told the Jackson Free Press that he did not have to heed Hood's warning, and continued to carry weapons wherever he wanted. In late July 2006, the head of the ACLU racial profiling division arrived in Jackson to address reports of racial profiling related to Melton's raids and techniques.

In September 2006, Mayor Melton, with his detective bodyguards and a group of youths, called the "lawn crew" because they traveled with Melton, ostensibly to help with neighborhood clean-up, raided half a duplex on Ridgeway Street without a warrant. Witnesses say that Melton attacked much of the rental duplex with a large stick. He cut his hand during the incident and had to go to the hospital for stitches. He reportedly returned with the young men, with sledgehammers to finish destroying that side of the duplex. Police arrested the tenant, Evans Welch, on drug possession, but he was discharged within days for lack of evidence. No warrant was issued for the raid, nor was the owner of the duplex—Jennifer Sutton—notified of any intention to conduct the raid or damage her property. After news of the demolition broke on Sept. 1, both the attorney general and the district attorney investigated the incident.

Melton and bodyguards Michael Recio and Marcus Wright were indicted on September 15, 2006, on multiple felony charges in the Ridgeway Street demolition, including burglary, conspiracy and the inducement of a minor to commit a felony. Melton was also indicted on three gun charges—a felony for carrying his weapon onto a college campus, two misdemeanors for the church and public park—the same day. Later in the year, Melton took a guilty plea on the gun misdemeanors and plead no-contest on the felony. The terms of both his bond and his probation for the gun charges did not allow him to be around firearms, supervise children under 17, leave his home past midnight without 48 hours' prior permission from his probation officer, consume drugs or alcohol, or use police equipment in any way. Melton, Michael Recio and Marcus Wright were acquitted on all counts filed in the Ridgeway Street incident on April 26, 2007. The prosecution dropped the inducement of a minor charge during the trial.

Some civil-rights leaders defended Melton, including Charles Evers, older brother of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers, and Stephanie Parker-Weaver, daughter of the first openly known interracial couple in Jackson. Parker-Weaver helped lead a campaign to convince Jacksonians of Melton's innocence, including a rally at City Hall with signs stating "Vote Melton Not Guilty." He also drew support from many white conservatives in Jackson who appreciated his crime-fighting methods. Prominent businessman Leland Speed, and families of similar conservatives, provided much of Melton's financial support. Melton told some conservatives that he would take the city past race politics, and explained why he ran as a Democrat. "Most of you are Republican," he said. "The reality is, if you're an African American in Jackson, you have to run as a Democrat to win." He added: "I don't like either party." He later on stated he viewed Joseph Stalin, John F. Kennedy, and Mao Zedong as his political influences, which caused him more controversy and cost him support from conservatives.

Other African American leaders, including the president of the state NAACP, Derrick Johnson, and the director of the ACLU of Mississippi, Nsombi Lambright, called for justice for the victims of Melton's unorthodox and illegal crime-fighting strategies. They said he was profiling poor blacks in the city. Those groups are leading an effort to start a civilian review board, in part in response to Melton's methods.

Melton was a member of the Mayors Against Illegal Guns Coalition, an organization formed in 2006 and co-chaired by New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg and Boston mayor Thomas Menino.

On November 16, 2007, Mayor Melton appointed Hinds County Sheriff Malcolm McMillin as Jackson's new police chief, after reassigning the police chief Shirlene Anderson to a new post within his administration. Sheriff McMillin decided to keep his post as Hinds County Sheriff in addition to acting as the chief of the Jackson Police Department, becoming the first person in Mississippi's history to serve as both County Sheriff and City Police Chief. After reviewing the applicable state laws and ethics rules, counsel determined the Sheriff could head both agencies legally and be compensated from both. He was confirmed by the Jackson City Council on a 4-2 vote. In securing McMillin as Police Chief, Mayor Melton promised not to interfere in the operations of the police department and to remain focused on other mayoral duties.

Controversies and criminal proceedings

July 19, 2006 - Jackson Mayor Frank Melton received criticism from advocates for the homeless when he used the city's emergency order to enforce a 10 p.m. curfew for the city's homeless population. According to Michael Stoops, executive director of the National Coalition for the Homeless in Washington, the curfew is the first of its kind in the nation. He also said that it effectively amounts to a modern Jim Crow law.

July 26, 2006 - Frank Melton raises security concerns with US House of Representative, and senior Homeland Security Committee Democrat, Bennie Thompson (MS) when Melton applied for, and was issued, a United States Capitol Police badge and identification card. The card allowed Melton, armed, to bypass security in Federal Buildings, congressional offices and Congress. Wilson Livingood, sergeant-at-arms for the U. S. House, stated in the report to Thompson dated Aug. 17 that Melton showed a Jackson Police Department credential to Capitol police.

August 26, 2006 - See above for Ridgeway incident.

Nov. 15, 2006 - Melton pleaded guilty to two misdemeanors for carrying a weapon into a church and a park, and no contest to a reduced charge on what had been a felony count involving a gun onto the grounds of the Mississippi College School of Law.

March 1, 2007 - Judge Tomie Green issued a warrant for the arrest of Frank Melton. The warrant was issued on the basis of probation violation because Melton resumed going on midnight club raids, while wearing an unofficial badge, among other possible violations.

March 7, 2007 - Frank Melton left the hospital in the early morning and returned home without alerting the Sheriff's Department. After his ankle bracelet alerted his probation officer that he was back at home, the sheriff called and told Melton to turn himself in to Hinds County authorities, where he was put into the medical ward of the jail.

March 8, 2007 - The Mississippi Supreme Court vacated the arrest warrant for Frank Melton, and asked that Hinds County Circuit Judge Tomie Green be recused without explaining the reasons for either decision.

April 24, 2007 - Frank Melton goes on trial for felony charges stemming September 15, 2006 demolition of a house on Ridgeway Street.

April 26, 2007 - Frank Melton is found not guilty on all counts.

February 2, 2009 - Melton's federal civil rights trial for demolishing the Ridgeway house began.

February 24, 2009 - Melton's federal civil rights trial ended in a mistrial when jurors notified the judge that they could not arrive at a verdict. The case was scheduled to be retried on May 11.

Mayoral re-election bid

Melton filed to run for re-election for the 2009 election. However, on March 17, 2009, the Jackson Democratic Municipal Executive Committee disqualified Melton in a unanimous vote because Melton did not meet the city's residency requirements. He did not file homestead exemption on his home in Jackson but on his home in Tyler, Texas, where his wife Ellen lives. The unanimous vote took Melton's name off the ballot for the May 5, 2009 primary.

Melton filed a lawsuit against the Jackson Democratic Municipal Executive Committee to have his name returned to the ballot. On March 26, 2009, Jones County Circuit Court Judge Billy Joe Landrum ordered Melton restored as a Democratic mayoral candidate. Landrum said Melton "overwhelmingly rebutted" the charge by showing documents with his Jackson home address, including his Mississippi driver's license, utility bills and voting records.

On May 5, 2009, Melton lost his bid for re-election, coming in third in the vote totals.

Death

On election night, Melton was rushed to the hospital. He had suffered a cardiac arrest at his Jackson home. He died shortly after midnight on Thursday, May 7, 2009, less than two days after losing the election. His wife, Dr. Ellen Melton, was at his side. He died at St. Dominic Jackson Memorial Hospital in Jackson, MS.

0 notes

Text

“The less we emphasize the Christian religion the further we fall into the abyss of poor character and chaos in the United States of America. ~Mississippi Governor Kirk Fordice, November 18, 1992, The New York Times

View On WordPress

0 notes