#Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols

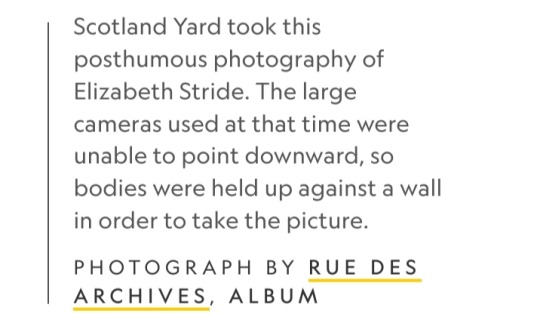

Text

By Parissa DJangi

August 18, 2023

Some say he was a surgeon. Others, a deranged madman — or perhaps a butcher, prince, artist, or specter.

The murderer known to history as Jack the Ripper terrorized London 135 years ago this fall.

In the subsequent century, he has been everything to everyone, a dark shadow on which we pin our fears and attitudes.

But to five women, Jack the Ripper was not a legendary phantom or a character from a detective novel — he was the person who horrifically ended their lives.

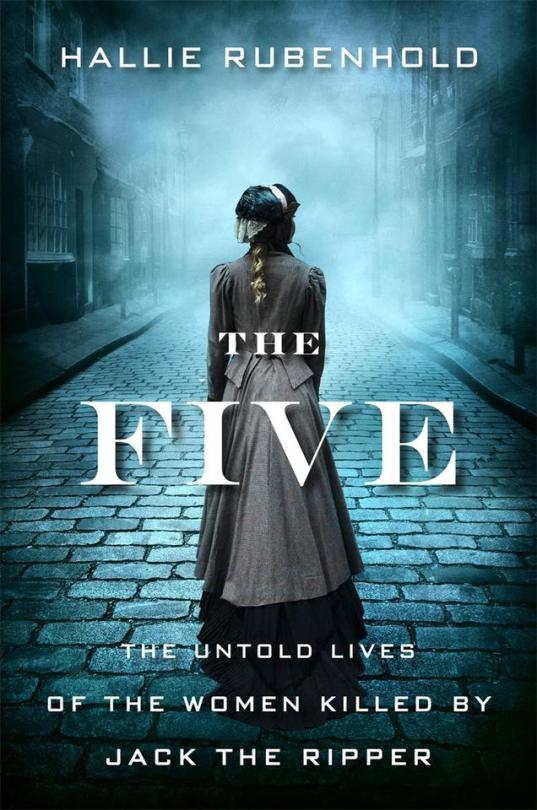

“Jack the Ripper was a real person who killed real people,” reiterates historian Hallie Rubenhold, whose book, The Five, chronicles the lives of his victims. “He wasn’t a legend.”

Who were these women? They had names: Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly.

They also had hopes, loved ones, friends, and, in some cases, children.

Their lives, each one unique, tell the story of 19th-century London, a city that pushed them to its margins and paid more attention to them dead than alive.

Terror in Whitechapel

Their stories did not all begin in London, but they ended there, in and around the crowded corner of the metropolis known as Whitechapel, a district in London’s East End.

“Probably there is no such spectacle in the whole world as that of this immense, neglected, forgotten great city of East London,” Walter Bessant wrote in his novel All Sorts and Conditions of Men in 1882.

“It is even neglected by its own citizens, who had never yet perceived their abandoned condition.”

The “abandoned” citizens of Whitechapel included some of the city’s poorest residents.

Immigrants, transient laborers, families, single women, thieves — they all crushed together in overflowing tenements, slums, and workhouses.

According to historian Judith Walkowitz:

“By the 1880s, Whitechapel had come to epitomize the social ills of ‘Outcast London,’ a place where sin and poverty comingled in the Victorian imagination, shocking the middle classes."

Whitechapel transformed into a scene of horror when the lifeless, mutilated body of Polly Nichols was discovered on a dark street in the early morning hours of August 31, 1888.

She became the first of Jack the Ripper’s five canonical victims, the core group of women whose murders appeared to be related and occurred over a short span of time.

Over the next month, three more murdered women would be found on the streets of the East End.

They had been killed in a similar way: their throats slashed, and, in most cases, their abdomens disemboweled.

Some victims’ organs had been removed. The fifth murder occurred on November 9, when the Ripper butchered Mary Jane Kelly with such barbarity that she was nearly unrecognizable.

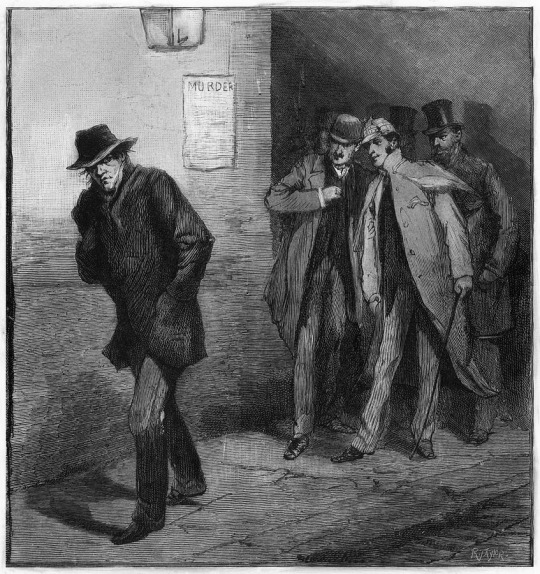

This so-called “Autumn of Terror” pushed Whitechapel and the entire city into a panic, and the serial killer’s mysterious identity only heightened the drama.

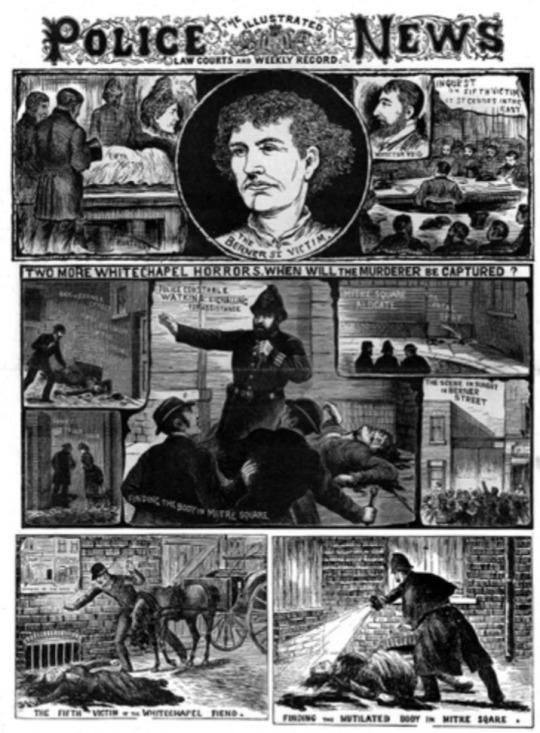

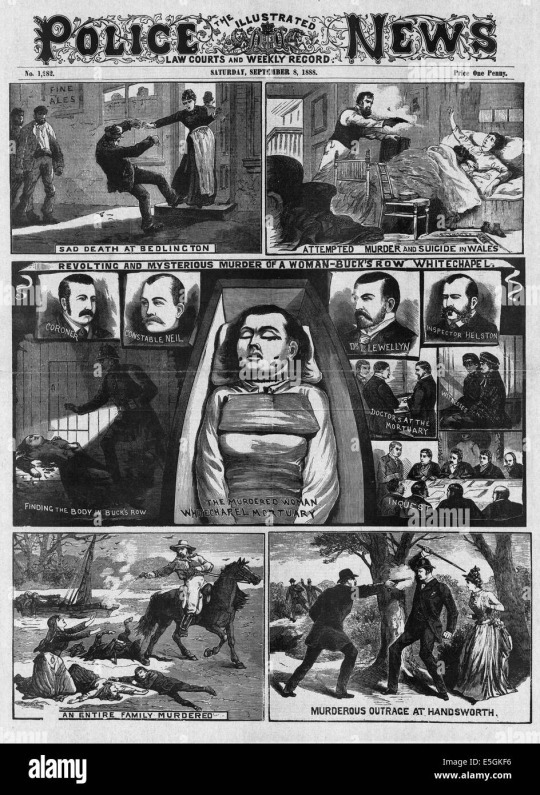

The press sensationalized the astonishingly grisly murders — and the lives of the murdered women.

Polly, Annie, Elizabeth, Catherine, and Mary Jane

Though forever linked by the manner of their death, the five women murdered by Jack the Ripper shared something else in common:

They were among London’s most vulnerable residents, living on the margins of Victorian society.

They eked out a life in the East End, drifting in and out of workhouses, piecing together casual jobs, and pawning their few possessions to afford a bed for a night in a lodging house.

If they could not scrape together the coins, they simply slept on the street.

“Nobody cared about who these women were at all,” Rubenhold says. “Their lives were incredibly precarious.”

Polly Nichols knew precarity well. Born in 1845, she fulfilled the Victorian ideal of proper womanhood when she became a wife at the age of 18.

But after bearing five children, she ultimately left her husband under suspicions of his infidelity.

Alcohol became both a crutch and curse for her in the final years of her life.

Alcohol also hastened Annie Chapman’s estrangement from what was considered a respectable life.

Annie Chapman was born in 1840 and spent most of her life in London and Berkshire.

With her marriage to John Chapman, a coachman, in 1869, Annie positioned herself in the top tier of the working class.

But her taste for alcohol and the loss of her children unraveled her family life, and Annie ended up in the East End.

Swedish-born Elizabeth Stride was an immigrant, like thousands of others who lived in the East End.

Born in 1843, she came to England when she was 22. In London, Stride reinvented herself time and time again, becoming a wife and coffeehouse owner.

Catherine Eddowes, who was born in Wolverhampton in 1842 and moved to London as a child, lost both of her parents by the time she was 15.

She spent most of her adulthood with one man, who fathered her children. Before her murder, she had just returned to London after picking hops in Kent, a popular summer ritual for working-class Londoners.

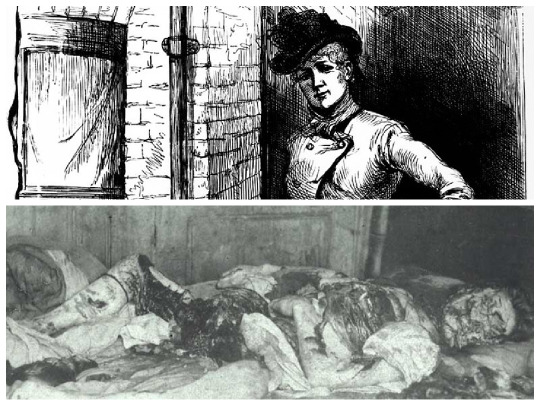

At 25, Mary Jane Kelly was the youngest, and most mysterious, of the Ripper’s victims.

Kelly reportedly claimed she came from Ireland and Wales before settling in London.

She had a small luxury that the others did not: She rented a room with a bed. It would become the scene of her murder.

Yet the longstanding belief that all of these women were sex workers is a myth, as Rubenhold demonstrates in The Five.

Only two of the women — Stride and Kelly — were known to have engaged in sex work during their lives.

The fact that all of them have been labeled sex workers highlights how Victorians saw poor, unhoused women.

“They have been systematically ‘othered’ from society,” Rubenhold says,"even though this is how the majority lived.”

These women were human beings with a strong sense of personhood. According to biographer Robert Hume, their friends and neighbors described them as “industrious,” “jolly,” and “very clean.”

They lived, they loved, they existed — until, very suddenly on a dark night in 1888, they did not.

A long shadow

The discovery of Annie Chapman’s body on September 8 heightened panic in London, since her wounds echoed the shocking brutality of Polly Nichols’ murder days earlier.

Investigators realized that the same killer had likely committed both crimes — and he was still on the loose. Who would he strike next?

In late September, London’s Central News Office received a red-inked letter that claimed to be from the murderer. It was signed “Jack the Ripper.”

Papers across the city took the name and ran with it. Press coverage of the Whitechapel Murders crescendoed to a fever pitch.

Newspapers danced the line between fact and fiction, breathlessly recounting every gruesome detail of the crimes and speculating with wild abandon about the killer’s identity.

Today, that impulse endures, and armchair detectives and professional investigators alike have proposed an endless parade of suspects, including artist Walter Sickert, writer Lewis Carroll, sailor Carl Feigenbaum, and Aaron Kosminski, an East End barber.

"The continued fascination with unmasking the murderer perpetuates this idea that Jack the Ripper is a game,” Rubenhold says.

She sees parallels between the gamification of the Whitechapel Murders and the modern-day obsession with true crime.

“When we approach true crime, most of the time we approach as if it was legend, as if it wasn’t real, as if it didn’t happen to real people.”

“These crimes still happen today, and we are still not interested in the victims,” Rubenhold laments.

The Whitechapel Murders remain unsolved after 135 years, and Rubenhold believes that will never change:

“We’re not going to find anything that categorically tells us who Jack the Ripper is.”

Instead, the murders tell us about the values of the 19th century — and the 21st.

#Jack the Ripper#Hallie Rubenhold#The Five#Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols#Annie Chapman#Elizabeth Stride#Catherine Eddowes#Mary Jane Kelly#19th-century#1800s#Whitechapel#London#Walter Bessant#Judith Walkowitz#Outcast London#East End#Autumn of Terror#Victorian society#Victorian era#Robert Hume#1888#Central News Office#Whitechapel Murders#Whitechapel Murderer#Leather Apron#murder#crime#mystery#unsolved case#National Geographic

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘On the Trail of Jack the Ripper’ by Richard Charles Cobb

‘On the Trail of Jack the Ripper’ by Richard Charles Cobb

Genre: Adult Non-Fiction – True Crime

Published: 2022

Format: Paperback

Rating: ★★★★

I’ve had a fascination with the Jack the Ripper mystery for years. Well, unsolved mysteries generally which started with the disappearance of the Princes in the Tower, and the death of Amy Robsart. But the Jack the Ripper mystery is a lot gorier and more disturbing.

This book discusses the five canonical…

View On WordPress

#Annie Chapman#Catherine Eddowes#Crime#Elizabeth Stryde#History#Jack the Ripper#liz stryde#mary ann nichols#Mary Jane Kelly#Murder#mutilation#neil r storey#Non Fiction#Pen and Sword#Polly Nichols#richard charles cobb#ripper#Serial Killer#True Crime#unsolved#unsolved murders

0 notes

Text

Funny what you hear...

A couple of days ago I found a TV series on YouTube that I haven't seen since 1973: "Jack The Ripper - Barlow & Watt Investigate".

It's an intriguing show, using two of the currently most popular TV policemen: they'd appeared in about three linked-but-separate crossover series, "Z Cars", "Softly Softly" and "Softly Softly Task Force".

However in this instance the crimes they're investigating, and the theories they're examining, are the notorious non-fictional Whitechapel murders.

*****

After about 50 years, watching this Is like seeing it for the very first time, and the very first episode contained the following exchange, which made me laugh a bit.

("Jack" is slang for a policeman, like "Bobby", "Peeler" or "cop", though I think Jack is more regionally North of England, where the Barlow and Watt characters originate.)

Barlow: "They had eight inspectors on the case."

Watt: "And two Lancashire Jacks are worth how many from the south?"

Barlow: "Well, at least we are Jacks. Starting with the evidence, and testing some theories. Not starting with the theory and selecting the evidence…"

*****

Why did I laugh?

It's because Barlow's final observation sums up Patricia Cornwell's infamous approach to her "Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper: Case Closed".

Like any detective-story writer, she started with her chosen perpetrator (artist Walter Sickert) then arranged the rest of the book to "prove" it was 'im wot dunnit.

It's a book crammed full of circumstantial evidence and leap-of-logic speculations such as "...while there is no evidence Sickert was in London on that date, there is no evidence that he wasn't".

Well, duh.

Cornwell goes after her target with such obsession that one reviewer - a lawyer - pointed out that if Sickert had been still alive, the book would have been Exhibit A in a case of malicious libel. (Another comment, however, suggested he would have revelled in such notoriety...)

*****

As for closing the Ripper case or providing solid proof of who he / she / they was or were, it won't happen; the speculation industry is worth too much money and new books, new names and new theories - or old stuff recycled - keep coming out, with the most recent in July of this year (2023).

The only names that really matter are Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols, Anne "Annie" Chapman, Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride, Catherine "Kate" Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly.

They were people, not just names to tick off a check-list.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 1 is officially over!

Congratulations to the actresses who made it to Round 2!

Round 2 will begin on Saturday, May 4th

The winners of Round 1:

Maude Adams

Anna Maria Alberghetti

Julie Andrews

Angela Baddeley

Hermione Baddeley

Lauren Bacall

Olga Baclanova

Pearl Bailey

Josephine Baker

Lucille Ball

Anne Bancroft

Tallulah Bankhead

Theda Bara

Mona Barrie

Jessie Bateman

Polly Bergen

Claire Bloom

Mrs Patrick Campbell

Diahann Carroll

Lina Cavalieri

Helen Chandler

Geraldine Chaplin

Ruth Chatterton

Claudette Colbert

Constance Collier

Gladys Cooper

Katharine Cornell

Phyllis Dare

Zena Dare

Ruby Dee

Judi Dench

Stephanie Deste

Marie Doro

Geraldine Farrar

Maude Fealy

Edwige Feuillère

Susanna Foster

Trixie Friganza

Jane Froman

Eva Gabor

Zsa Zsa Gabor

Mary Garden

Greer Garson

Dusolina Giannini

Hermione Gingold

Dorothy Gish

Lillian Gish

Frances Greer

Mata Hari

Dolores Hart

Olivia de Havilland

Jill Haworth

Audrey Hepburn

Libby Holman

Lena Horne

Sally Ann Howes

Ethel Irving

Diane Keaton

Lisa Kirk

Eartha Kitt

Angela Landbury

Carol Lawrence

Vivien Leigh

Lotte Lenya

Beatrice Lillie

Bambi Linn

Gillian Lynne

Heather MacRae

Jayne Mansfield

Mary Martin

Jessie Matthews

Siobhán McKenna

Meng Xiaodong

Helen Menken

Ethel Merman

Cléo de Mérode

Evelyn Millard

Liza Minnelli

Rita Moreno

Odette Myrtil

Pola Negri

Julie Newmar

Nichelle Nichols

Maureen O’Sullivan

Aida Overton Walker

Anna Pavlova

Bernadette Peters

Lily Pons

Rosa Ponselle

Lee Remick

Diana Rigg

Thelma Ritter

Chita Rivera

Ginger Rogers

Lillian Russell

Rosalind Russell

Diana Sands

Lizabeth Scott

Maggie Smith

Emily Stevens

Susan Strasberg

Barbra Streisand

Yma Sumac

Inga Swenson

Laurette Taylor

Hilda Trevelyan

Monique Van Vooren

Fannie Ward

Ethel Warwick

Elisabeth Welch

Mae West

Anna May Wong

Diana Wynyard

Yoshiko Yamaguchi

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Canonical Five

Case #1: Mary Ann/Polly Nichols

Date of Death: August 31st 1888

Physical Description: 5’2”, brown eyes, high cheekbones, graying dark brown hair

Family Life

Mary Ann was born to Edward Walker and Caroline Walker, being one of three children. Her brothers were named Edward Walker and Frederick Joseph Walker.

Mary Ann was married to William Nichols at age 18 and they had five children together; Edward (1866), Percy (1868), Alice (1870), Eliza (1877), and Henry (1879). The couple eventually separated due to Mary Ann’s alcoholism and prostitution alongside the suspected cheating William underwent with the nurse who helped deliver Henry.

Death

Being the first victim, Mary Ann was the least practiced. She had no organs removed, something that later becomes an MO of JTR, but she was found with a white handkerchief, a comb, and a piece of a mirror. She was missing five teeth, alongside other slash injuries. She was described as lying lengthwise along the street with her left hand touching a gate.

Mary Ann is particularly interesting in her connections to the lore of the show because, clearly, she’s being represented by Virginia seeing as she has all three of the children; Alice, Edward, and Henry. Seeing as Alice is a child in this woman’s life, it rules out the possibility of her being Mother Alice. She also doesn’t align with what we know Mother Virginia to look like, seeing as she has brown eyes and hair, unlike our blonde-haired blue-eyed devil.

What I think this could suggest is that there is an original timeline in which a different version of Mother Virginia had all three children. To me, this is ringing several Creeler bells. The original description of Mary Ann closely resembles both Joyce and Karen in S1 (though Karen is taller than 5’2”). It could apply to either of them, except Joyce only has two children as far as we know. None of her children hold semblance to the seen Creel children outside of the comparisons made between Henward and Will which are intended to explain Vecna’s fascination and crave for him rather than familial implications.

Now, the Wheeler family doesn’t perfectly match the Creel family. Instead of two sons, Karen has two daughters. Nancy has brown hair rather than blonde. Holly is blonde and blue-eyed, but Henry was a boy. Mike fits the least, but at the same time he would be filling the role of Edward as the outcast of the family in combination with his other isolating traits.

Karen potentially being Daughter Virginia from Edward’s timeline would make the Wheelers a direct parallel to this original timeline Creel family. I could drawl on similarities between Alice and Nancy, Edward and Mike, and Holly and Henry (which I might do another post for), but this is all to say that I believe there was an original timeline before Edward was banished. This delves into speculation, but I find it very intriguing that Mary Ann was found with a piece of mirror in her pocket at her death and Edward’s banishment in the show is surrounded by mirror shards. Almost like parallels. Or something.

I have a whole post here discussing why I am almost completely certain that Edward was Jack the Ripper. This first kill is incredibly important as a kick starter, but I’ll admit I’m still unsure of who removed Edward and how it was done. I’m also trying to keep these short, so it’s not as detailed as usual, sorry!!

#trying a different post format for this part#i wanna do silly little case files for the victims so when i try to explain a Potential timeline i can just link stuff#plus people are more likely to read short things#jtr parallels#i think that was the tag?#the canonical five#virginia creel#edward creel

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Canonical Five: Mary Ann Nichols

August 17, 2022

I’ve been not posting as much lately but I wanted to come back with a bang and do Jack the Ripper, one of my favourite true crime cases of all time. However, instead of just doing a post on the entire case I figured I’d do a deep dive into each of the victims.

I know Jack the Ripper most likely had more victims than just these five women, however the Canonical Five has become extremely infamous in this case and each woman deserves their own post in my opinion.

Here we go.

Mary Ann, also known as “Polly” to friends and family, was born Mary Ann Walker on August 26, 1845 in Dean Street, Soho, London. She was the second child of Edward and Caroline Walker.

At 18 years old Mary Ann married a man named William Nichols on January 16, 1864 at Saint Bride’s Parish Church in the City of London. The couple first lived at 30-31 Bouverie Street, but eventually moved In with Mary Ann’s father at 131 Trafalgar Street.

The couple had five children together: Edward John (born in 1866), Percy George (born in 1868), Alice Esther (born in 1870), Eliza Sarah (born in 1877) and Henry Alfred (born in 1879).

Shortly after their fifth child Henry was born, Mary Ann and William moved into their own home at 6 D-Block Peabody Buildings on September 6, 1880, paying a weekly rent. However, this did not last for long and the couple separated with William taking four of their children to live near Old Kent Road.

Mary Ann’s father accused William of leaving Mary Ann due to an affair he supposedly had with the nurse who had been there when their son Henry was born, though William claimed that him and Mary Ann had kept their marriage going for at least three years after this alleged affair. William insisted that the reason for their separation was due to Mary Ann’s heavy drinking and he had only started an affair after Mary Ann had left him. William had told authorities later on that Mary Ann had left him and began practicing sex work.

In 1881, Mary Ann was residing at Lambeth Workhouse, though she left this workhouse on May 31st. She did eventually return to the workhouse on April 24, 1882. She did move back with her father for a period of time in 1883 before moving out again following a quarrel.

Back in these days you legally had to support your wife, despite them being separated, William Nichols would pay Mary Ann a weekly allowance of five shillings until the spring of 1882, when he found out she was working as a sex worker. William stopped making these payments due to this, and explained to the authorities that his wife had deserted him and his family, living with another man and involved in sex work.

William was not required to pay his wife if she was earning money through sex work, so Mary Ann no longer was receiving anything from her husband.

The money Mary Ann did make from sex work was often spent on alcohol.

In April 1888, Mary Ann began working as a domestic servant to Mr and Mrs Cowdry in Wandsworth. However, this did not last long and she left after only working there for 3 months, stealing clothes with her when she left. She lived in a common lodging-house for a period of time before moving to 56 Flower and Dean Street in Whitechapel on August 24, 1888.

Around 11pm on August 30, 1888, Mary Ann was seen walking along Whitechapel Road. She visited the Frying Pan public house in Brick Lane, Spitalfields, leaving at 12:30am on August 31.

By 1:20am, she had returned to her lodging-house, and within the hour she was seen by the deputy lodging house keeper who asked her to pay for her bed for the night there. Mary Ann replied she had no money and she was ordered to leave. She said she would earn money and be back to get her bed.

The last time Mary Ann Nichols was seen alive was by a woman named Emily Holland, where she was seen walking alone down Osborn Street around 2:30am. She was notably drunk according to Emily and at one point was slumped against the wall of a grocery shop.

Emily had tried to get Mary Ann to go back to her lodging-house, but Mary Ann refused telling her she had already earned her money for the bed three times over but had spent it each time. The two parted with Mary Ann walking towards Whitechapel Road.

At 3:40am, a man named Charles Allen Cross found what he believed to be a tarpaulin lying on the ground in front of a gated stable entrance in Buck’s Row, Whitechapel as he was walking to his workplace. Inspecting closer, Cross discovered that it was actually the body of a woman who was laying on her back with her eyes open, her legs straight, and her skirt raised above her knees. Her left hand was touching the gate of the stable entrance.

Another man on his way to work, Robert Paul, saw Cross standing in the road looking at the body and both men examined the body together. Cross had touched the woman’s face which was still warm, then her hands which were cold. Cross thought the woman was dead, but Paul thought she might just be unconscious. The men pulled her skirt down and went to find a policeman. Constable Jonas Mizen was sent to examine the body while the men went on their way to work.

Before Mizen got there, another policeman, John Neil had come across the body and was using a lantern to examine. While he was doing this he got the attention of Constable John Thain who was passing the entrance to Buck’s Row, which Neil shouted, “Here’s a woman with her throat cut. Run at once for Dr Llewellyn.”

Neil found no blood trails with his lantern, and also examined the road but found no marks of wheels.

Surgeon Dr Llewellyn arrived at Buck’s Row at 4am and found two deep knife wounds on the woman’s throat, determining her deceased. The doctor determined she had only been dead for 30 minutes upon discovery, as her body and legs were still warm. He ordered Neil to take the body to the mortuary where he could then further examine her.

Police questioned all the tenants of Buck’s Row, including those who lived on the property closest to where the woman’s body had been discovered. Several residents claimed to be awake at that time but no one heard or saw anything. All police who had been patrolling around the area at that time also claimed to have seen nothing suspicious.

It was discovered that both sides of the woman’s face had been bruised by either a first or the pressure of a thumb before the throat wounds had been inflicted. One of the wounds measured 8 inches in length, and the other one measured to be 4 inches. Both reached back to her vertebral column and were inflicted from left to right.

The woman’s genitals had been stabbed twice, her abdomen mutilated with one deep, jagged wound 2 or 3 inches from the left side. Several incisions had been inflicted across the abdomen, causing her bowels to protrude through. Three or four similar cuts ran down the right side of her body. The knife used was estimated to be at least 6-8 inches long, possibly a cork-cutter or shoemaker’s knife.

Each wound had been violent and in a downward thrusting manner. The doctor believed that whoever did this had some kind of anatomical knowledge. None of the woman’s organs were missing.

Dr Llewellyn estimated that this would have taken the murderer 4-5 minutes to complete. He also believed the woman had been facing her attacker when he held his hand across her mouth before cutting her throat. She would have died instantly and all of her injuries were made by the murderer after she died. The doctor believed this because there was little blood.

The woman had no identification on her at the time of her death, and the only possessions she had was a white pocket handkerchief, a comb, and a piece of mirror. Her petticoats were marked “Lambeth Workhouse P.R.” so they believed that is where she resided. The matron of the workhouse could not identify the body, a workhouse inmate named Mary Ann Monk positively identified the woman as being Mary Ann Nichols at 7:30pm on August 31. Emily Holland had also positively identified her earlier that day.

On September 1, 1888, William Nichols corroborated this discovery as being his estranged wife, stating “I forgive you, as you are, for what you have been to me.”

The first day of the inquest heard testimony from three witnesses. The first was Mary Ann’s father, who claimed his daughter had been separated from William Nichols for about 7 or 8 years. He also said he had not seen his daughter since Easter and she had no known enemies.

Constable John Neil also testified, claiming the actual location of the murder was dimly lit, the closest light being a street lamp shining at the end of the row. Neil also said that Whitechapel Road was pretty busy even at the time of the discovery, so it’s possible that Mary Ann’s killer could have escaped in that direction.

Dr Llewellyn also testified, stating that Mary Ann had 5 missing teeth, a slight laceration on her tongue, a bruise running along the lower part of her jaw on the right side of her face. This could have been caused by a blow from a fist or pressure from a thumb. He further described her injuries and stated that no blood was found on the body or clothes. The injuries may have been done by a left-handed person and all of Mary Ann’s injuries had been done by the same instrument.

A man named Harry Tomkins testified that he had not left his place of work after 1am on August 31 and him and his colleagues did not hear anything suspicious. Tomkins said his workplace was very quiet, but said he was too far away from the crime scene to have been able to hear any cries for help.

Inspector Joseph Helson testified that Mary Ann had not been carried to the location where her body was found, she had been killed there.

William Nichols testified again and claimed to have not seen his wife in three years and that she had left him of her own accord because of her drinking. He stated he had no knowledge of his wife’s whereabouts in the years before her death.

It was determined that if Mary Ann’s murderer was walking around with blood on them after the attack, it would not have looked strange as this was Whitechapel in 1888 and many slaughterhouses were around. It wasn’t strange to see someone with blood on them during this period of time.

By the time the inquest was completed, another murder of similar nature had occurred, with a woman named Annie Chapman being murdered on September 8, 1888. Many consider her to be the second canonical five murder, and she also was found with similar bruising on her face and horrific injuries.

Mary Ann Nichols and Annie Chapman had a lot of similarities, both involved in sex work, being estranged from their husbands, and being around the same age. Annie Chapman’s murder will be discussed in further detail in the second instalment of this series.

A 20 minute deliberation took place, and the jury came back concluding that Mary Ann Nichols had been murdered perhaps by someone she didn’t know.

Mary Ann’s murder had occurred within 300 yards of two previous murders of two other women named Emma Smith and Martha Tabram. All of the murders had occurred within a 5 month period, but they were clearly different. What led many to believe they were committed by the same person was the geographical location, and some do believe that Emma Smith and Martha Tabram are Ripper victims, however many do not.

A reporter named Ernest Parke suggested in the August 31 edition of The Star, that these murders were committed by a single killer. Many others began to adopt this theory as well. In the week after the inquest closed on Mary Ann Nichols, two more women were murdered in similar fashion, Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes.

Any suspicions of a serial killer soon became confirmed as all of the women had been killed by a similar modus operandi, and eventually in October of 1888, the killer named himself Jack the Ripper.

Before any of this however, there was a rumour going around that a local Jewish man named John Pizer known as “Leather Apron” who made footwear from leather may have murdered the women. He was known to carry a knife and did not like sex workers.

There was no direct evidence against him but he was arrested on September 10, 1888. A search of his home was conducted where they found 5 long-bladed knives, however Pizer was soon released after confirmation of his alibis. He later received compensation from at least one newspaper who had named him a murderer.

Mary Ann Nichols was buried on September 6, 1888, with her father, estranged husband and three of her children in attendance. She was buried in the City of London Cemetery. Her coffin had a brass plaque with the inscription, “Mary Ann Nichols, aged 42; died August 31, 1888.”

Mary Ann Nichols is considered the first victim of the canonical five and many consider her the first Jack the Ripper victim. In the next part, the murder of Annie Chapman will be covered.

#unsolved#UNSOLVED MYSTERIES#unsolved case#unsolved murder#unsolved true crime#true crime#Crime#london#jack#the#ripper#victim

32 notes

·

View notes

Link

[ad_1] The still-unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper killed his first known victim on this day in history, Aug. 31, 1888. On this day, a woman named Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols, 43, was found murdered in London's Whitechapel neighborhood. Nichols, who had a known drinking problem and previously worked as a prostitute, was last reported seen around 2:30 a.m. She had told someone that she was going out to make money to pay for lodging, according to the website Jack the Ripper 1888. ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, AUGUST 30, 1984, SPACE SHUTTLE DISCOVERY BLASTS OFF FOR ITS MAIDEN VOYAGEHer body was discovered lying in the streets a little more than an hour later. The man who discovered her, delivery driver Charles Cross, initially thought the body was a disposed tarp. Due to the dark night, neither Cross nor another person he called over to observe the body did not notice that her throat had been deeply slashed, almost to the point of decapitation, said the website. A memorial marker of Mary Ann Nichols, believed to be the first known victim of Jack the Ripper, at the City of London Cemetery. (Loop Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)Shortly thereafter, police constable John Neil encountered the body of Nichols. Neil reported that "there was not a soul about" and that he had earlier been to the area and had not noticed anyone. "I was on the right side … when I noticed a figure lying in the street. It was dark at the time … I examined the body by the aid of my lamp, and noticed blood oozing from a wound in the throat," he told officials during an inquest into Nichols' murder. ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, AUGUST 4, 1892, LIZZIE BORDEN'S FATHER AND STEPMOTHER ARE MURDERED IN MASSACHUSETTS"She was lying on her back, with her clothes disarranged. I felt her arm, which was quite warm from the joints upwards. Her eyes were wide open. Her bonnet was off and lying at her side," he said. Neil then flagged down another police officer, who summoned a doctor. Nichols was officially pronounced dead at 4 a.m., just five days after her 43rd birthday. A 1965 picture of Durward Street, formerly known as Bucks Row. The street was the location of Mary Ann Nichols' murder on Aug. 31, 1888. The street's name was changed months after the murder. (WATFORD/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images)It was later discovered that Nichols' throat was not her only wound: She had been slashed deep in the abdomen and had been disemboweled by her killer, said the website. These injuries were concealed by her clothing. Nichols would not be identified until the following day. ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, JULY 11, 1804, AARON BURR MORTALLY WOUNDS ALEXANDER HAMILTON IN DUELHer murderer, however, is still unidentified all these years later — although there are many theories about the person's identity. Nichols is known as the first of the "canonical five" victims of "Jack the Ripper," a serial killer with an unknown death toll. The last of the "canonical five," Mary Jane Kelly, was discovered murdered on Nov. 9, 1888, said the Encyclopedia Britannica. A scene from the 1959 film "Jack the Ripper." The serial killer's identity is still unknown all these years later. (Paramount/Getty Images)The "canonical five" were so named as they each had their throats slit. The five women were sex workers and were believed to have been soliciting on the nights of their murders, noted the encyclopedia. The name "Jack the Ripper" came from a Sept. 27, 1888 letter sent by the purported killer to the British newspaper Central News Agency. In the letter, the author boasted of quickly killing the women and promising to kill even more, said the website History House. There have been several suspects posited as Jack the Ripper. The letter was signed "Jack the Ripper." As Jack the Ripper is still unknown, he could be responsible for all or some of the canonical five murders. ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, FEB. 16, 1968, FIRST 911 CALL IS MADE, THE EMERGENCY SYSTEM FUELED BY SHOCKING MURDERHe also is suspected of several other killings in the Whitechapel neighborhood, but it is impossible to prove how many were actually committed by Jack the Ripper, authorities have said.There have been several suspects posited as Jack the Ripper: These include a lawyer and teacher named Montague Druitt; a Russian criminal and physician named Michael Ostrog; and a Polish immigrant named Aaron Kosminski, noted Encyclopedia Britannica. Tour guide Joel Robinson, right, leads a group of visitors and tourists on a Jack the Ripper tour in London on Aug. 24, 2020. More than a century after the murders, the crimes still fascinate many people. (TOLGA AKMEN/AFP via Getty Images)Other perhaps more outlandish and less plausible suspects for the Jack the Ripper killings include members of the British royalty as well as American serial killer H.H. Holmes. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTERIn the 135 years since Nichols was found murdered, the Jack the Ripper story continues to fascinate. Locations of the murders and other notable events connected to the victims are stops on the "Jack the Ripper Tour," says its website. CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APPAdditionally, there have been numerous books and movies made about the murders — and speculation continues to this day on just who "Jack" really was. Christine Rousselle is a lifestyle reporter with Fox News Digital. [ad_2]

0 notes

Text

L’invenzione di jack lo squartatore: la vera storia sulle vittime

L’invenzione di jack lo squartatore: la vera storia sulle vittime

Hallie Rubenhold, nel libro Le cinque donne, traccia non solo la storia documentatissima delle vittime del presunto serial killer (Mary Ann Nichols, detta Polly – Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes e Mary Jane Kelly), mettendo in discussione anche l’esistenza stessa di Jack the Ripper, attribuendone la definizione comoda al sensazionalismo dei giornali e alla stessa cultura…

View On WordPress

#Controllo#Corpi#Cultura dello Stupro#Cultura Patriarcale#Diritti#Età Vittoriana#Hallie Rubenhold#Modelli culturali#Moralismo#Stereotipi

0 notes

Photo

Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols (née Walker; 26 August 1845 – 31 August 1888) was the first canonical victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have murdered and mutilated at least five women in the Whitechapel and Spitalfields districts of London from late August to early November 1888.[2][3]

The two previous murders linked to the Whitechapel murderer are unlikely to have been committed by Jack the Ripper, although the murder of Mary Ann Nichols was initially linked to this series, increasing both press and public interest into the criminal activity and general living conditions of the inhabitants of the East End of London.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Ann_Nichols

0 notes

Photo

November 25 is the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. The premise of the day is to raise awareness of the fact that women around the world are subject to rape, domestic violence and other forms of violence; furthermore, one of the aims of the day is to highlight that the scale and true nature of the issue is often hidden.

Between 1873 and 1891 eleven poor and working class women (pictured, Ada Wilson, Emma Elizabeth Smith, Martha Tabram, Annie Chapman, Mary Ann Nichols, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, Mary Jane Kelly, Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie and Frances Coles) were attacked and murdered in London’s East End by a killer(s) who was never caught, and other 7 (including Annie Millwood and Elizabeth Jackson, and 5 unidentified ones) suffered a similar fate. They were murdered just because they were women and their murderer(s) was a misogynistic psycho.

While the killer(s) went onto have a large amount of tours and walks, studies and published works (regarding who he might was, different theories as why he did it), the victims were divided in categories and some of them completely forgotten. So here you find a list of research/non-fiction books about these women, if you are interested to know more about them (the list is going to be updated when new books are published, thanks).

· BEGG, Paul & BENNETT, John (2014): The forgotten victims.

· CHAUVET, Didier (2002): Mary Jane Kelly: La dernière victime.

· FROST, Rebecca (2018): The Ripper’s Victims in Print. The Rethoric Portrayals Since 1929.

· HUME, Robert (2019): The hidden lives of Jack the Ripper’s victims.

· KEEFE, John. E. (2010, revisited 2012): Carroty Nell. The last victim of Jack the Ripper.

· RANDALL, Anthony J. (2013): Jack the Ripper. Blood lines.

· RUBENHOLD, Hallie (2019): The Untold Lives of the Women killed by Jack the Ripper / The Lives of Jack the Ripper’s Women.

· SCOTT, Chris (2005): Will the real Mary Kelly…?.

· SHELDEN, Neal E. (2013): Mary Jane Kelly and the Victims of Jack the Ripper: The 125th Anniversary.

· SHELDEN STUBBINGS, Neal (2007): The Victims of Jack the Ripper.

· WHITTINGTON-EGAN, Richard (2015): Mr Atherstone Leaves the Stage. The Battersea Murder Mystery: A Twisting and Tragic Tale of Love, Jealousy and Violence in the age of Vaudeville.

· YOST, Dave (2008): Elizabeth Stride and Jack The Ripper.

**

You may be interested in the “A Hidden History of Women in the East End: The Alternative Jack the Ripper tour” to know how these women lived in Victorian Whitechapel.

May they never be forgotten.

**

Please note, if you have/know about more books about these women’s LIVES, you may contact me here. Thank you very much.

#victims#books#ada wilson#emma elizabeth smith#Martha Tabram#Annie Chapman#Mary Ann Nichols#polly nichols#elizabeth stride#Catherine Eddowes#mary kelly#rose mylett#Alice McKenzie#Frances coles#emma smith#kate conway#Kate Kelly#mary jane kelly#marie jeannette kelly#Catherine Millett#Clay Pipe#Carroty Nell#november 25#25 november#international day for the elimination of violence against women#special dates#women's rights#Violence against women#women's history#history of women

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’m never gonna let my Jack the Ripper AU die send help

#my art#jack the ripper#monster stomp#ripper row#mary jane kelly#mary ann nichols#au#doodles#traditional art#victorian#polly#marie jeanette kelly

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack the Ripper Walking Tour

Jack the Ripper Walking Tour

While I was in London with a friend back in November we went on a Jack the Ripper walking tour in Whitechapel. It’s something that had been on my bucket list for a while, and I was so excited when I finally got to do it. They’re obviously popular as we saw three other tours when we were out as well! Jack the Ripper is one of those enduring historical mysteries that is still fascinating today, and…

View On WordPress

#1888#Annie Chapman#bucks row#Catherine Eddowes#dorset street#elizabeth stride#goulston street#hanbury street#Jack the Ripper#London#martha tabram#mary ann nichols#Mary Jane Kelly#mitre square#Murder#Places#Polly Nichols#serial killer#ten bells#walking tour#whitechapel

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jack The Ripper: The Murders [Part 1]

Since the story of Jack The Ripper is quite long and complicated, I have divided it into three parts. This is the first part and covers who the victims were and how they were killed.

Introduction

The most famous serial killer is, without a doubt, Jack The Ripper. The story is well-known; brutal murders, anonymous letters, and an unknown killer. This real-life horror story begins on 30 August 1888 in Whitechapel, England.

Mary Ann Nichols

The first victim was 43-year-old Mary Ann Nichols, sometimes called Polly. Polly had gotten married in her late teens and had five children with her husband. Their marriage lasted for 16 years and they parted ways in 1880. It is not known why their marriage ended, but one factor was Polly's alcoholism. Polly left her children with her ex-husband and started working as a part-time maid, but left her occupation to work as a prostitute. She continued to drink heavily and spent most of her money on buying alcohol. Polly spent the remaining amount on housing in different flophouses in Whitechapel.

Polly was last seen alive on the night of 30 August by her roommate from the flophouse she was currently residing in. The roommate noted that Polly was extremely intoxicated and tried to convince Polly to go back to the flophouse, but Polly refused. Polly died a couple of hours later.

Polly's body was found in the early morning of 31 August by a man named Charles Allen Cross. Polly was lying on her back with her eyes open, and Cross was unsure whether she was dead or passed out. He alerted a policeman nearby, and a doctor named Dr. Llewellyn was sent to the crime scene. There was almost no blood at the crime scene, but Dr. Llewellyn quickly realized that Polly was dead. Polly's body was moved to the mortuary where Dr. Llewellyn began his examination. Polly had been dead for about half an hour when she was found, and she had sustained several brutal injuries. Her throat had been cut from ear to ear, her viscera were exposed, and she had been stabbed several times in the vagina. She had sustained these injuries after death, which explained the lack of blood at the crime scene. Polly was identified by her roommates at the flophouse.

It is believed that the perpetrator was interrupted during his horrifying attack since his later murders were far more brutal.

Annie Chapman

The second victim was a 47-year-old woman named Annie Chapman. She was, just like Polly, working as a prostitute at the time of her death and was dependent on alcohol. Annie had previously been married to a man named John James Chapman, with whom she had three children. Annie's eldest daughter died at the age of 22, and her son was born with a disability that made him physically impaired. Annie suffered from depression following her daughter's death and was soon a full-fledged alcoholic. The couple divorced in 1884, and her ex-husband gained custody of their children. It was at this time Annie started selling sex and stayed at various flophouses.

Annie was killed on 8 September 1888, a little over a week after Polly's murder. Around 5 a.m, a witness heard a woman screaming and the sound of someone falling against a fence. Annie's dead body was discovered about one hour later, and she was taken to the mortuary. Annie had sustained similar injuries as Polly, which made the police believe that they had been attacked by the same person.

A woman claimed to have seen Annie shortly before her death. Annie had been talking to a tall man in his 40s with dark hair. It could never be confirmed to 100 percent that the woman she had seen was Annie.

Elizabeth Stride

Elizabeth Stride was born in 1843 in Torslanda, Sweden. She was raised a Christian but went down the path of prostitution early in her life. Elizabeth gave birth to a stillborn child in 1865 and moved to London one year later. She learned to speak English and soon got married to a man named John Thomas Stride. The couple never had any children, and they separated after a couple of years. Elizabeth lived in flophouses until she met a man named Michael Kidney. She moved in with Kidney and lived with him on and off for the remainder of her life. Their relationship was rocky and sometimes violent, and she moved out just a few days before her death. Elizabeth was found dead outside on 30 September 1888. The same doctor who had examined Annie's body carried out the examination of Elizabeth. Her throat had been cut, just like the two previous victims.

Some believe that Elizabeth was not a victim of Jack The Ripper, since her murder did not fit the modus operandi of Jack. For example, her body had not been mutilated, and her turbulent relationship with Michael Kidney suggested that he could be the killer.

Catherine Eddowes

Catherine Eddowes was born in 1842 and had a rough childhood. She was orphaned at the age of 15 and had to start working to support herself. Catherine met Thomas Conway, a former soldier, shortly after the death of her parents. Catherine and Thomas had a relationship for a couple of years which resulted in the couple having three children together. However, she left Thomas and her kids in 1880 and started selling sex to support herself. She barely had enough money to survive, and could not even afford a bed in a flophouse.

Catherine was found dead on 30 September 1888. Her body was found shortly after Elizabeth's body had been discovered and it was determined that the women had been killed roughly one hour apart. Catherine's throat had been cut and she had several wounds on her face. Her abdomen had been cut open and her viscera had been placed on her shoulder. Part of her kidney was missing.

Mary Jane Kelly

The fifth, and possibly the final victim, was Mary Jane Kelly. She was born in Ireland in 1863 but moved to London in 1884. She had previously been married, but her husband had passed away in an accident. Mary supported herself by working as a prostitute and moved into a small apartment in 1888. However, Mary could seldom afford the rent. On 9 November 1888, her landlord sent his assistant to Mary's apartment to collect the rent. The assistant knocked on the door several times, but Mary did not open it. He looked into the apartment via a broken window and saw Mary's dead body lying in her bed. He alerted the police who soon arrived at the crime scene.

Mary had suffered far more brutal injuries than the previous victims. Her throat had been cut and part of her nose, eyebrows, cheeks, and ears had been removed. Her breasts had been removed and her abdomen had been cut open. Mary's breasts and her intestines had been placed around her corpse and she had several wounds on her arms. Her heart had been cut out and part of her right lung had been torn out.

Some people doubt that Mary was a victim of Jack The Ripper. Just like the murder of Elizabeth Stride, there were several inconsistencies in Jack's regular modus operandi. Mary had been killed inside, whereas the other victims had been murdered outside. Mary was also in her mid-20s when she died, but the other victims were in their 40s. Her body was also far more mutilated than the other women.

#tcc#true crime#true crime community#tc original#true crime original#my post#jack the ripper#murder#serial killer#crime#unsolved murder#creepy

179 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Five: The Untold Loves of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper, Hallie Rubenhold

[Indie bookstores|Amazon]

#RadioWest#podcast#books#non-fiction#library#murder#Jack the Ripper#Polly Nichols#Anne Chapman#Elizabeth Stride#Catherine Eddowes#Mary Jane Kelly#mystery#death#history#victims

0 notes

Photo

Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols née Walker (26 August 1845 – 31 August 1888)

Polly was the daughter of a blacksmith born in August 1845 in a cramped 8 foot by 10 foot room in a dilapidated building on Fleet Street. The family of five would have lived together in that single room. Unusually for the era Polly was sent to school until the age of 15 as her father was firm supporter of education and she may have been the only person in her family who could both read and write. In 1852 Polly's mother died of Tuberculosis and as the only girl Polly would have been expected to take on much of her late mother's role in the home, cooking and cleaning and caring for her younger sibling, despite her young age. Sadly none of them was aware that little Fredrick, who was only 3, had been exposed to his mother's disease and he passed away 19 months later.

When Polly was sixteen she met William Nichols who was three years older and they married when she was 18. Within 3 months Polly was expecting her first child. Unfortunately this child died at one year and 9 months old. Within four years Polly had given birth to five children and Polly and William decided to find a place of their own. They were fortunate enough to find lodgings in 1876 in the Peabody Buildings, built by philanthropic American millionaire George Peabody. It was a requirement that tenants had to be clean and of good moral character in order to be successful in their application for housing in Peabody's tenements. In 1878 Polly gave birth to her sixth child and things began to change. Polly left William several times in 1880, returning to her father's property apparently because William "had turned nasty" and she believed her husband was having an affair with a neighbour, Rosetta. Polly had also started to drink, a behaviour that would have led to her being evicted if she had not walked out of her own volition, apparently unable to tolerate her husband’s infidelity any longer. This would have earned Polly a reputation of being unfit and immoral for abandoning her husband and children.

Polly survived by seeking a bed to sleep in at the workhouse, where she would have been fed watered down porridge and expected to work unpicking rope in exchange. Many would rather beg and sleep rough than stay in the workhouse and Polly did end up living on the streets. The work available for women at the time, such as casual domestic service, laundry or factory work was so poorly paid that it was almost impossible to live on. One way for destitute women to find better circumstances for herself, then as it is now, is to find a man who could provide some security. As a woman, Polly could not divorce her husband on the basis of adultery alone, even if she could afford to; although a man could divorce his wife on this basis. William was legally obliged to pay Polly a maintenance as she had proven that she was destitute by entering the workhouse, but he hired a private investigator to establish whether Polly was living with another man, which would absolve him of this financial duty to his wife. Polly was indeed in a relationship with another man and William put his evidence before the Magistrate's Court in 1882 and proved his wife's "adultery without consent". Polly was now without a regular income and deemed to be a "sexually immoral" woman for having a relationship with a man who was not her husband. In an act of true hypocrisy by 1883 William was living in a new address with his five children and Rosetta or "Mrs Nichols" as she was known to her neighbours. Polly was able to seek support from her father and brother but it appears that by this point Polly's taste for drink was well established and possibly further fuelled by her sense of shame caused by her circumstances. Ultimately her drunkenness made life impossible for her family and in 1884 she decided to leave and was once again out on the street.

In 1886 Polly's brother died after a paraffin lamp exploded in his home, setting him on fire. Polly was now the only surviving sibling and the same year her then partner left her for another woman, meaning yet another return to the workhouse. In 1886 as part of a scheme to help destitute women, Polly was placed in a house to be employed as a servant. It is unknown why this broke down but less than 6 months later Polly lost her position. By 1887 Polly was begging on the streets and sleeping rough, frequently in Trafalgar Square with hundreds of other homeless people and living hand to mouth. Police Constables would attempt to move people on and Polly was arrested for refusing to do so and for resisting Police. In 6 years Polly had gone from being a respectable woman, a wife and a mother, to a foul mouthed drunken beggar.

Polly was released in October 1887 on the instruction that she must go into the workhouse or face arrest. Once again Polly found herself in the workhouse until she discharged herself in December. By January the cold and damp took it's toll and Polly was admitted to an infirmary and in April 1888 was transferred to the workhouse yet again. Once again a placement was found for Polly as a servant, by the same Matron at the workhouse who had found her her previous placement in 1886, as when not drunk Polly was well spoken, clean and polite. The family she was placed with in May 1888 bought her clothing and a few personal items such as a hairbrush, combs and pins. As the only servant she had her own room and bed and would have been fed three meals a day. Presumably this would have been like paradise but for unknown reasons Polly absconded in July 1888, taking the clothing and goods she had been provided with her. It is likely that Polly probably pawned these items so that she could pay for food and lodgings. Polly went to Whitechapel, where lodging houses were cheap, which would have allowed her to stretch her newly acquired money further. There she paid for a bed on a nightly basis at a female only lodging house, sharing a room with three other women. She befriended another resident Ellen Holland who testified that Polly stayed at the lodging house until approximately 24 August 1888 when her money seemed to be running out. Once again she was out on the street. On 31 August Polly had been drinking in "The Frying Pan" pub and decided to try her luck securing a bed at the lodging house at around midnight, even though she had drunk away all of her money. Polly was given short shrift and sent on her way by the lodging keeper. At 2:30am she was seen by Ellen Holland, who was returning to the lodging house after watching a large fire at the dry dock. She described Polly as staggering and unable to walk straight due to her intoxication and chatted to her for a few minutes, trying to persuade her to come back to the lodging house with her. Polly refused, as she had no money and possibly also because of the confrontation she had had with the lodging keeper earlier. Ellen Holland is the last person to see Polly alive, other than her killer, as she watched her sway off into the darkness in search of somewhere to sleep for the night. Polly's body was discovered at 3:40am by Charles Allen Cross.

Victorian society assumed that women like Polly living in such circumstances, and walking the streets at night or early hours of the morning, must be earning money by prostituting themselves. However, there is no evidence that Polly was a prostitute; she was never arrested for solicitation and at the coroner's inquest into her murder those who knew her asserted that they had never known her to sell sex for money. This, however, was mostly ignored by the press who widely misreported that Polly was a prostitute. The Police also had a theory that her murder was the work of a "high rip gang" ( a group that extorted money from prostitutes) or alternatively, that it was a lone "prostitute murderer". Therefore, it did not suit their theory, which shaped their entire investigation, for Polly to merely be a homeless drunk trying to find somewhere safe to sleep when she was murdered. And so, Mary Anne 'Polly' Nichols became the first known victim of Jack the Ripper, one of the Canonical Five.

[Source: The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper by Hallie Rubenhold (2019)]

NEXT ->

#TS3#The Sims 3#The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack The Ripper#The Canonical Five#1 of 5

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack The Ripper Part 1 - Mary Nichols

Disclaimer: I do not condone anything I write about in these cases. Every case I cover is for educational purposes. I do not mean any disrespect to anyone covered in this case.

Jack the Ripper

Jack the ripper is one of England’s, possibly the world’s, most infamous criminals. The perpetrator has never been captured or identified. The five canonical murders happened between August 31st and November 9th 1888, although since Jack the ripper was never caught it is unknown if these were the only crimes committed.

The first victim of the ripper is heavily debated; however, it is generally accepted that Mary Nicols is the first canonical victim. Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols was born Mary Ann Walker on 29th August 1845 in SoHo, London. Mary married William Nichols on 16th January 1864 at age 18. The couple had five children. After sixteen years of marriage, they separated due to unknown causes, William moved out of their shared home with four of their kids. After their separation, Mary lived in workhouses and lodging houses and supported herself with her earnings from her prostitution work.

After the separation Mary moved around a couple of workhouses before moving in with her father again. Due to William being legally required to support Mary, she was given five shillings a week for allowance until he was informed, she was working as a prostitute in 1882. Mary spent her remaining years in workhouses and boarding houses.

Mary Nichols was seen alive at various times during the night of the 30th August and early morning on the 31st August, she had been seen at 11pm on Whitechapel Road, 1:20am at her lodging house on Flower and Dean Street and then again at 2:20am by the lodge house keeper. Mary Nichols was last seen alive at 2:30am walking alone down Osborne Street (approx. one hour before her murder). Emily Holland, who reported seeing Mary at this time, said she saw Mary noticeably drunk. Emily tried to convince her to go to a lodging house but she refused as she did not have enough money, the two parted and Mary walked towards Whitechapel Road.

At 3:40am, a man named Charles Allen Cross discovered what he initially believed to be a tarpaulin lying on the ground in front of a stable entrance in Bucks Row, Whitechapel, as he walked to work. Upon inspecting the object, he discovered it was the body of a woman. She lay on her back with her eyes open, legs out straight, her skirt raised above her knees and her left had touching the stable entrance. Robert Paul, a cart driver on his way to work, approached the location and followed Charles Cross to the body. The two men didn’t know whether Mary was unconscious or dead, they pulled her skirt down and searched for a policeman.

When the police and surgeon arrived, Mary Ann Nichols was pronounced dead at the scene.

Mary had two deep knife wounds on her throat as well as seven others, it was thought she had been dead for around 30 minutes due to her body and legs were still warm. No organs were missing. It was thought that all her abdominal injuries would have taken less than five minutes to complete. While examining the crime scene, the police found no blood trails and no marks of wheels.

After a 3 day inquest, Mary’s murder was ruled a “wilful murder against some person or persons unknown”.

Mary Ann Nichols was buried on 6th September 1888 in the City of London Cemetery.

#crime#true crime#jack#jack the ripper#unsolved#unsolved crime#unsolved case#unsolved true crime#england#london

2 notes

·

View notes