#Mont Blanc 100th Anniversary

Text

📸 Dave M. Benett

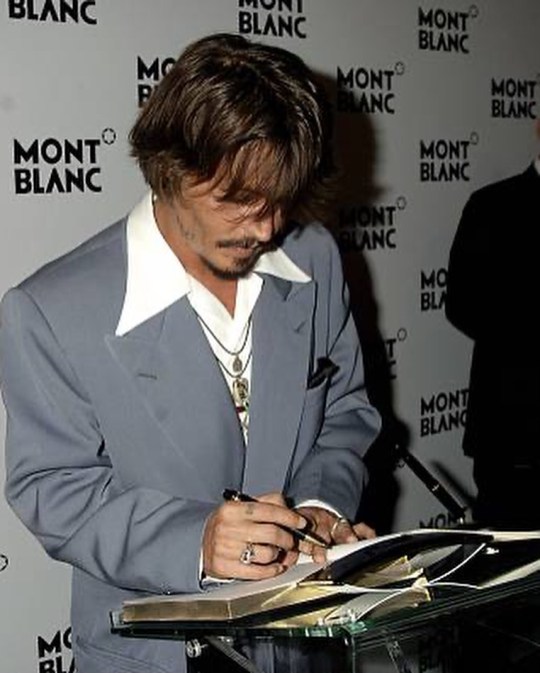

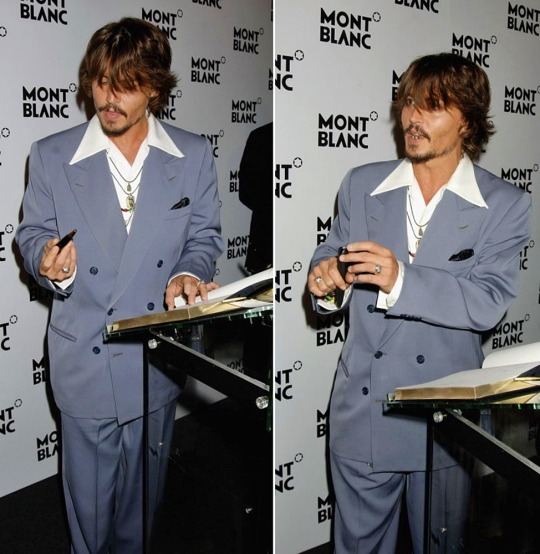

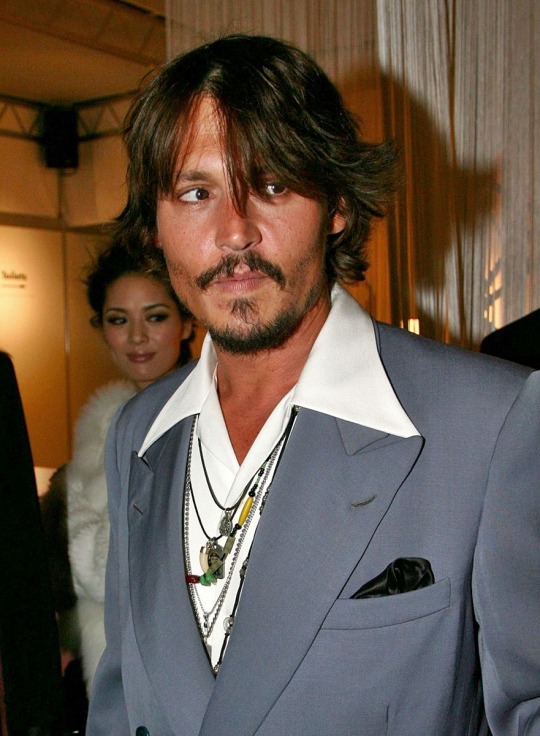

Johnny Depp attends 100th Anniversary gala celebration in a fantastic recreation on the summit of Mont Blanc at the World famous Watch Fair in #Geneva, Switzerland on #April 05, 2006 #pen

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

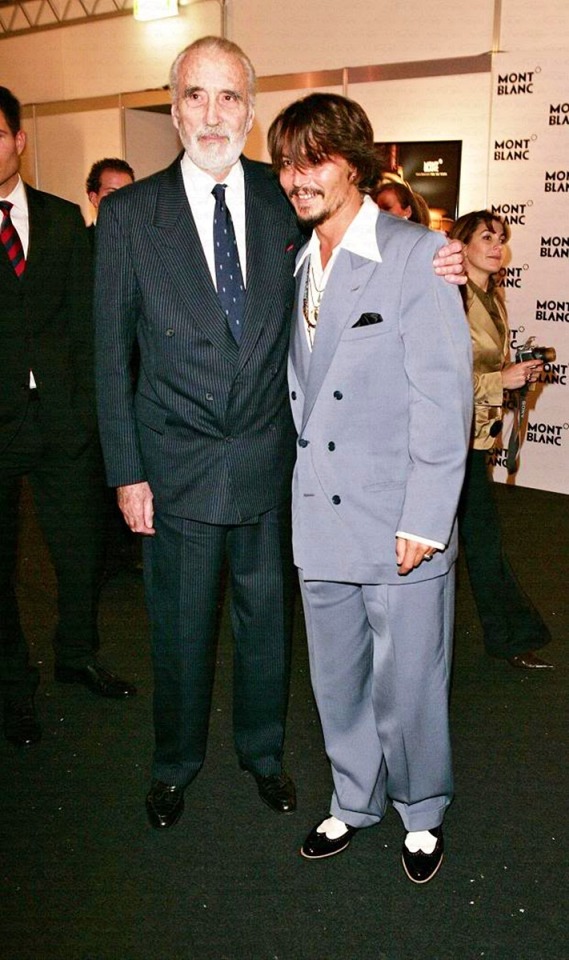

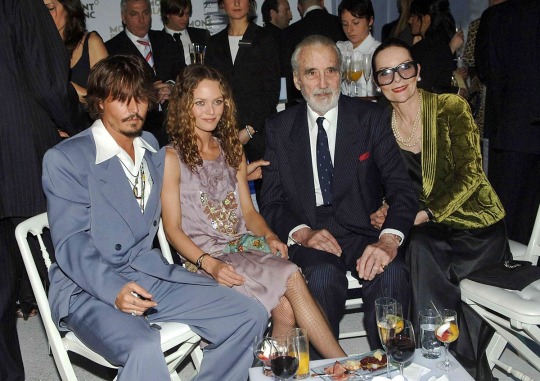

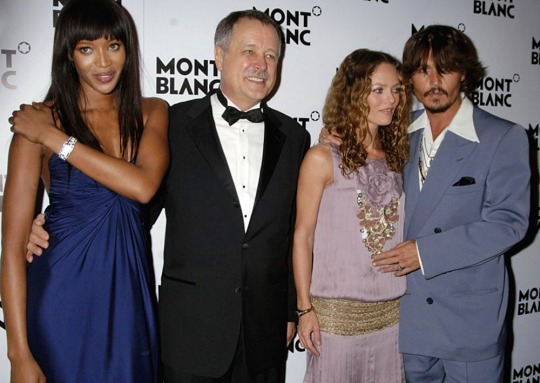

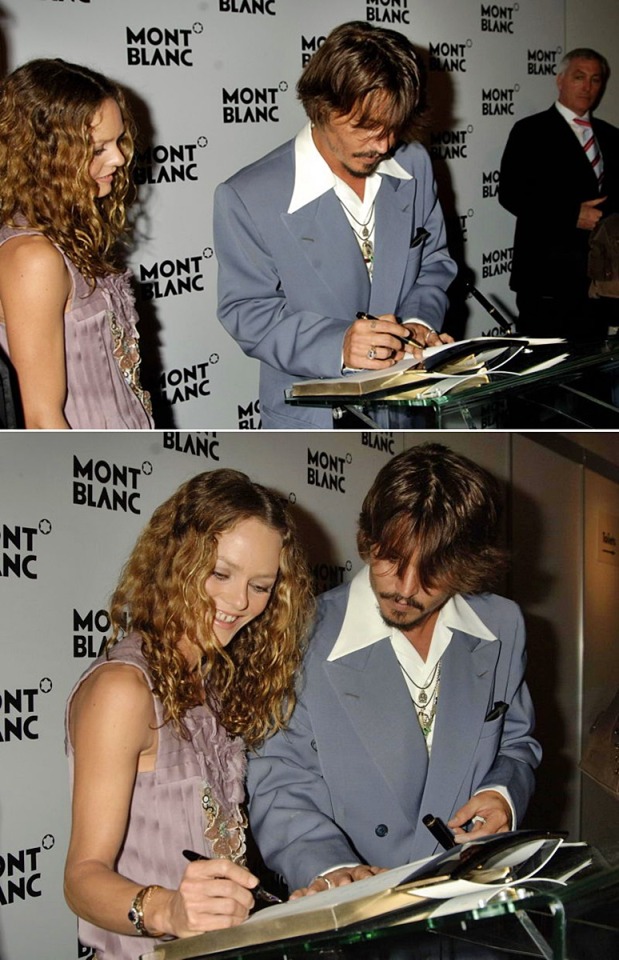

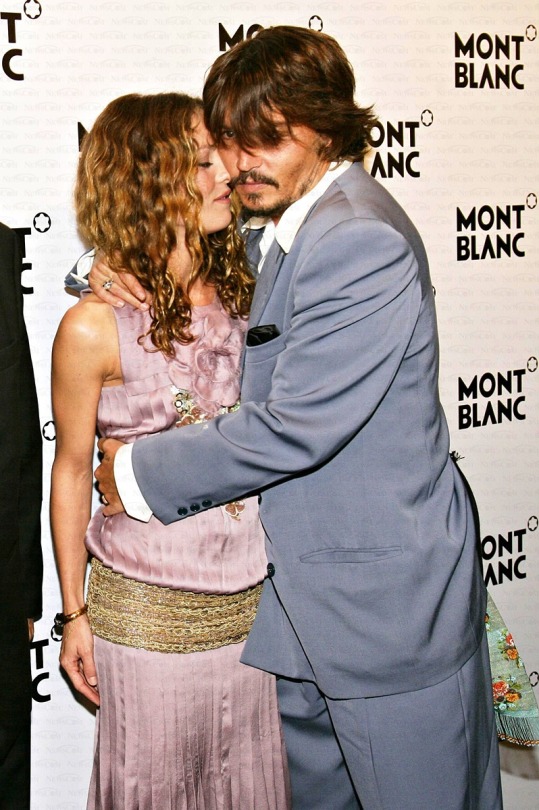

Behind the Scenes: Johnny Depp, Vanessa Paradis, Christopher Lee and his wife Gitte Lee, Naomi Campbell and the CEO of Montblanc Wolff Heinrichsdorff during the the Mont Blanc 100th Anniversary Celebration Gala, 16 years ago, on this day (April 5), at the Palexpo Convention Center, in Geneva, Switzerland.

#Johnny Depp#Vanessa Paradis#April 2006#Christopher Lee#Gitte Lee#Naomi Campbell#Wolff Heinrichsdorff#Geneva#Switzerland#Palexpo Convention Center#Mont Blanc 100th Anniversary#Attending Events

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johnny Depp attends Mont Blanc’s 100th Anniversary Gala Celebration during the Watch Fair in Geneva, Switzerland (April 5th, 2006)

#johnny depp#celeb#icon#actor#musician#john christopher depp ii#ilovejohnnydepp#iloveyoujohnnydepp#marc blanc#Geneva Switzerland#2006#2000s#2000s icons#2000s actors#2000s hollywood#2000s photography

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The silence after the blast: How the Halifax Explosion was nearly forgotten

HALIFAX -- A boy presses his small face up to a cold window pane. It's an early winter morning, and two ships in Halifax harbour are exchanging a cacophony of horn blasts.

Vessels use these loud whistles as they pass, the boy's mom explains.

But today, Dec. 6, 1917, they do not pass.

The Norwegian relief vessel, the SS Imo, collides with a French munitions ship laden with explosives, the SS Mont Blanc. For 19-1/2 minutes, a dazzling display of fireworks captivates onlookers as the Mont Blanc drifts and burns.

The toddler, playing with a toy train on the kitchen window sill, watches the flames engulf the ship -- the last images he will ever see.

At 9:04 a.m., the Mont Blanc blows up with devastating force, its 2,600 tons of explosives levelling swaths of Halifax and Dartmouth, raining down shards of white-hot iron, blowing off roofs and shattering glass -- including the windows of a small wooden house in the city's north-end Richmond neighbourhood.

There, at age two years and seven months, Eric Davidson is blinded in the Halifax Explosion.

"My father was still looking out and all the glass came in on his face and his upper body," his daughter, Marilyn Elliott, said in an interview.

"Doctors looked at him and determined that his eyes couldn't be saved. Both of his eyes were removed that day. In an instant, a little baby, a happy-go-lucky baby, is without sight."

As a little girl, Elliott grew up knowing her father was blinded in the horrific blast that claimed nearly 2,000 lives, injured 9,000 and left 25,000 homeless. But it wasn't a topic that was openly discussed in her family.

The wartime disaster was mentioned in passing, in hushed tones, with a heavy heart.

"My grandmother was a changed woman after the explosion. She grieved the loss of her baby boy's eyesight," Elliott said. "It was a permanent trauma that she carried with her the rest of her life."

A hundred years after the greatest human-made blast before the atomic bomb, the country is commemorating the explosion's centennial with a large memorial service at Fort Needham Memorial Park. Dozens of organizations have received grants for museum and art exhibitions, theatre productions, documentary films and concerts. Canada Post has issued a striking commemorative stamp, a new plaque has been erected, a time capsule created and books published.

But the Halifax Explosion anniversary wasn't always so publicly remembered.

For many years, Dec. 6 passed quietly in this East Coast town, with a small service or private prayers, but no official public ceremony marking one of Canada's worst humanitarian disasters.

In the wake of a deafening blow and billowing white smoke that rose thousands of metres above the harbour, a silence settled over the city: It would take decades before the blackout was lifted, and the heartwrenching stories of the Halifax Explosion told.

"People tried to forget it. You don't carry that stuff around."

Jim Cuvelier, a 101-year-old survivor of the Halifax Explosion, said the disaster wasn't spoken of when he was growing up.

"People tried to forget it. You don't carry that stuff around," said Cuvelier, a baby who was at home on Lady Hammond Road on the outskirts of the blast zone at the time of the disaster. "I never heard them talk about it."

Mothers couldn't bear the deaths of innocent babies. Children disappeared without a trace. Others turned up days later in makeshift morgues. Girls and boys struggled to comprehend being suddenly orphaned. Wives mourned their husbands, killed instantly in harbourfront factories. Soldiers grappled with the insurmountable trauma of watching homes burn to the ground, families still inside, the scent of burning flesh in the air.

"The city was devastated. It was such a cataclysmic event, so traumatic, that I think people probably didn't want to revisit those horrors," said Craig Walkington, chairman of the Halifax Explosion 100th Anniversary Advisory Committee. "It really did do incredible damage. There was virtually no family that wasn't touched by it, whether injuries, fatalities, or a loss in some way."

The horrors witnessed by survivors on that day 100 years ago were, for many decades, unspeakable. The blast wiped out much of Halifax's densely populated north end and parts of Dartmouth, including a Mi'kmaq settlement known as Turtle Grove, and badly damaged the African-Nova Scotian community of Africville.

The shock wave of the explosion was felt as far away as Cape Breton, and windows nearly 100 kilometres away cracked. It was followed by a towering 15-metre tsunami, drowning survivors near the shore and sweeping many bodies out to sea. Upturned cook stoves ignited fires that consumed wooden homes, scorched entire blocks and made the rescue of some injured survivors trapped inside homes impossible.

That night, a blizzard blanketed the city with more than 40 centimetres of snow. "It got cold and the snow buried bodies. The next three days were a horror story," local author and historian Dan Soucoup said. "They found children two or three days later huddled and frozen in the snow."

Relief efforts were badly hampered by the cold and snow. Still, miraculous stories emerged from the rubble.

A soldier walking through the flattened Richmond neighbourhood a day after the explosion heard a faint whimper coming from a burned-out house. He walked through the charred debris and there, protected under an ashpan, he found a baby girl. The 23-month-old orphan, nicknamed 'Ashpan' Annie, was burned but alive.

In some cases, entire families were killed. In others, one survivor lived on. One woman, Mary Jean Hinch, lost 10 children and her husband in the explosion. Pregnant and alone, she was rescued after being pinned under lumber for 24 hours. She and her unborn son were the only survivors in her family.

Other harrowing tales from the front lines speak of near mythical courage. A train dispatcher, Vince Coleman, spent his final minutes warning an incoming train of the impending blast, prompting it to halt in its tracks and saving passengers and crew. In another case, most of the crew aboard the Stella Maris died attempting to attach a line to the Mont Blanc to tow it away from bustling Pier 6.

"He worked for 40 hours removing eyes."

The disaster, towards the end of the First World War, made headlines around the world.

"I have newspapers from all over the world. The Halifax Explosion shared the headlines with the major war-time events. It was not just some local thing," said Janet Kitz, author of several books on the Halifax Explosion.

As stories of the disaster got out, generosity flooded in. Children in Brantford, Ont., gave up their Christmas presents to raise money for the children of Halifax, donating $15,000 for relief efforts. People in Truro, N.S., lined the tracks at the rail station waiting to help the waves of refugees that arrived from Halifax in need of food and shelter.

The city's hospitals were inundated with wounded survivors and several emergency medical stations were set up in schools and clubs. Although aid arrived from across Canada and the United States -- particularly Boston, a city Nova Scotia still thanks every year with a Christmas tree -- many of the first medical responders on the scene hailed from nearby communities. Doctors, nurses and firefighters from across the Maritimes showed up to take on the harrowing task of aiding the injured.

George H. Cox, a doctor and eye specialist from New Glasgow, about 150 kilometres northeast of Halifax, arrived at the Rockingham train station outside Halifax the next day. With the tracks into the city destroyed, he trudged through deep snow to Camp Hill Hospital. Men, women and children lined the corridors, many with glass, pottery, brick, mortar and nails stuck in their eyes. He quickly realized that the large number of ocular injuries required his expertise.

"He worked for 40 hours removing eyes. He had a bucketful of eyes," Soucoup said. "He chased everybody out, slept for three hours, and did that again."

Halifax's mortuaries were also overwhelmed. Bodies, charred and frozen, were stacked like firewood outside funeral homes. Many unidentified corpses were stored in a school basement. Funerals went on for weeks, and services for the unidentified bodies drew thousands of mourners.

"Everything that could go wrong did go wrong."

As the body count climbed, bereaved locals, politicians and newspaper editors began questioning the cause of the blast and demanding to know who was responsible for the calamity. Details of the collision emerged during a judicial inquiry and legal proceedings, though few got the answers they were seeking.

When the Mont Blanc, laden with thousands of tons of explosives, came upon the Imo on the wrong side of the harbour, it asserted its right-of-way using loud whistles -- the very horn blasts that attracted little Eric Davidson.

"The Mont Blanc did have the right to the channel. But the Imo was stuck on a course it couldn't get out of," said Joel Zemel, an author and historian. "By the time they realized it, it was too late to avoid an accident. Everything that could go wrong did go wrong."

The initial investigation pinned the blame on three men: The Mont Blanc's captain, its pilot and the Royal Canadian Navy's chief examining officer in charge of the harbour. Given the Mont Blanc's explosive cargo, it was said that the burden rested with its crew to avoid a collision at all costs.

In the end, however, the Supreme Court of Canada and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London found both the Mont Blanc and Imo were equally to blame for the navigational errors that led to the crash. No one was ever convicted in the disaster.

Yet questions persisted, like why the crew of the Mont Blanc didn't scuttle the ship, or steer it out to sea. "They were criticized heavily for being cowards," Zemel said. "But it would have taken six hours to sink the boat. And they thought they only had 10 seconds, not 19-and-a-half minutes."

The ship's cargo included wet and dry picric acid, TNT, gun cotton, benzol and other ammunition. "They were just a floating bomb. They could have tried to warn people but they didn't want to die. It was run for your life," he said.

"The city went to sleep until the Second World War."

Despite the enormity of the catastrophe, Halifax was forced to slowly pick up the pieces and move on. Swaths of the city had been levelled, and rebuilding was necessary to assuage the misery and anguish of survivors. Tents on the Commons had given way to rows of wood and tarpaper tenements near the current site of the Halifax Forum, but more permanent homes were desperately needed.

Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden promised the full resources of the federal government would be placed at the city's disposal, said Barry Cahill, author, researcher and member of the Halifax Explosion advisory committee.

Nearly $30 million was set aside for the Halifax Relief Commission to assist with medical care, rebuild infrastructure and establish pensions for injured survivors. One of the commission's lasting legacies is Canada's first public-housing project, the Hydrostone development not far from the blast site itself. "They had the good sense to retain a famous English town planner, Thomas Adams," Cahill said. The English-style garden suburb was completed in 1920.

As homes, churches, schools and factories were rebuilt, Halifax residents pushed the terror of the explosion from their minds, in part out of necessity. With hard times ahead, people struggled to get on with their lives.

"It wasn't an easy time in the 20s and 30s. There was a lot of depression here. Economically it was a difficult time in the Maritimes," Soucoup said. "The city went to sleep until the Second World War."

Halifax survivors were also fatigued by the news of endless First World War casualties in Europe.

"People were a wee bit hardened because of war," Kitz said. "The Nova Scotia Highland Regiment was at Passchendaele and several hundred men had been killed and wounded. Each day brought newspaper lists of those killed in action and hospital ships carrying wounded men arrived regularly."

"Somehow you were expected to just get on with it."

It took generations for the disaster to be commemorated. After the one-year anniversary, the city didn't hold another official public memorial until the 50th anniversary in 1967. Church services were observed and small ceremonies organized, but Halifax's collective psyche was not yet ready to publicly recall the calamitous blast that claimed so many lives.

"It could have been too painful in the early days," Elliott said, noting that even after the service in 1967 it once again fell by the wayside. "Why was it forgotten? No one has the answer to that. It could have been a sign of the times. Back then, people didn't like to dwell on misfortune. It wasn't really talked about."

Kitz wonders if the commemoration of the Halifax Explosion would have been different had it happened in another part of the city.

"It happened in the north end of the city, where it was mainly working-class people. If City Hall had been destroyed or the big businesses of the south end had been decimated, it would have been slightly different maybe. It's hard to say. Somehow you were expected to just get on with it. And that's what people did."

It was Kitz's tenacious research that helped change that.

In 1980, she penned an original undergraduate essay on the Halifax Explosion that led her to uncover boxes of mortuary artifacts gathering dust in the dark basement of Province House. She carefully catalogued objects that belonged to the dead, such as a child's Richmond School notebook with the words "Thou Eternity Away Forever" scrawled at the bottom of a page. "I quickly found it wasn't the objects in themselves that were intrinsically interesting. It was the people behind the objects," Kitz said.

She interviewed survivors who had been children in 1917, many of whom had never spoken of the enormous explosion out of respect for the impenetrable grief of their parents.

"Their mothers would never speak of it, because many of the fathers and children had been killed," Kitz said. "For a mother who lost perhaps a husband and two children ... it must have been just appallingly difficult. I don't think the mothers could ever have spoken openly of what they went through."

But older children who had survived the explosion opened up to Kitz about what transpired on that winter day so long ago. "They were eager to share their stories. Many of the younger survivors had very vivid, personal stories," Kitz said. "It wasn't so absolutely desperate for the children. There was almost a pride about being a survivor."

Kitz helped fundraise for a monument to victims of the disaster. In 1985, the Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower was opened at Fort Needham Memorial Park overlooking the explosion site. Survivors and those wishing to pay their respects now had a place to assemble.

Kitz also helped mount an exhibit on the disaster at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in 1987, and two years later her best-selling book Shattered City further revived interest in the explosion.

Elliott, whose father passed away in 2009, offered another theory as to why the city nearly forgot about a seminal event that shaped its history: Survivors simply weren't ready to confront their memories.

"Those impacted the most by the explosion needed time."

from CTV News - Atlantic http://ift.tt/2Asz06E

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halifax Explosion - December 6, 1917

Halifax Explosion – December 6, 1917

Halifax (Nova Scotia, Canada) was devastated on 6 December 1917 when two ships collided in the city’s harbour.

Taken from the Dartmouth side Results of the deadly blast

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion.

On Dec. 6, 1917, the Belgian relief ship Imo rammed into the French munitions vessel Mont-Blanc, which was carrying TNT through the narrowest part of Halifax harbour. A…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

DEC 16-17 from @zuppatheatre — TICKETS ON SALE NOW (link in bio) Part of the Halifax Explosion 100th Anniversary Commemorations • AT THIS HOUR The Deposition of Harbour Pilot Francis Mackey • a site-specific, verbatim theatre performance • In the room where it happened On the days it took place With the words that were spoken 100 years ago • Saturday, December 16th at 2:00pm & 7:30pm • Sunday, December 17th at 2:00pm & 7:30pm • The Halifax Provincial Court 5250 Spring Garden Road • On December 6, 1917, in the narrows of Halifax Harbour, the Belgian Relief vessel IMO collided with an overloaded French munitions ship, Mont-Blanc. The resulting massive explosion wreaked havoc on both sides of the harbour and left at least 2000 people dead. Within hours Ottawa ordered a full investigation. Despite chaos in the city the Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry began the following week at the Halifax Provincial Court on Spring Garden Road. • Using excerpts from the inquiry's transcripts, At This Hour offers a personal account of what happened that terrible morning through the words of Francis Mackey, the pilot on board Mont-Blanc. The charged exchanges between Pilot Mackey and the lawyer representing the owners of IMO, Charles Burchell, reveal how a supposed search for truth became the pursuit of a convenient scapegoat. • Who was to blame? A century later, this question is still unanswered. • Janet Maybee’s book Aftershock - The Halifax Explosion and the Persecution of Pilot Francis Mackey, inspired the creation of At This Hour. • Adaptation and Direction : Ben Stone Sound and Projection Design : Brian Riley History Consultant : Janet Maybee http://ift.tt/2zWSvE6

0 notes

Text

Johnny Depp attends 100th #Anniversary gala celebration in a fantastic recreation on the summit of #Mont Blanc at the World famous #Watch Fair in #Geneva, Switzerland on #April 05, 2006 #pen #Vanessa

1 note

·

View note

Photo

16 years ago (2006), on this day (April 5), Johnny Depp and Vanessa Paradis attended the Mont Blanc 100th Anniversary Gala Celebration, at the Palexpo Convention Center, in Geneva, Switzerland.

> Curiosity:

At that time, Johnny was in the middle of the filming of “Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End” in Bahamas, thus the tanned skin.

#Johnny Depp#Vanessa Paradis#Mont Blanc 100th Anniversary#Geneva#April 2006#Palexpo Convention Center#Switzerland#Lovely Couple#Attending Events

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johnny Depp and Vanessa Paradis attend Mont Blanc’s 100th Anniversary Gala Celebration during the Watch Fair in Geneva, Switzerland (April 5th, 2006)

#johnny depp#celeb#icon#actor#john christopher depp ii#musician#ilovejohnnydepp#iloveyoujohnnydepp#mont blanc#vanessa paradis#geneva switzerland#2006#late 2000s#2000s hollywood#2000s actors#2000s#2000s icons

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johnny Depp attends Mont Blanc’s 100th Anniversary Gala Celebration during the Watch Fair in Geneva, Switzerland (April 5th, 2006)

#johnny depp#actor#celeb#icon#john christopher depp ii#musician#ilovejohnnydepp#iloveyoujohnnydepp#watch fair#mont blanc#Geneva Switzerland#100th#gala#2006#2000s photography#late 2000s#2000s hollywood#2000s actors#2000s#2000s icons

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johnny Depp attends Mont Blanc’s 100th Anniversary Gala Celebration during the Watch Fair in Geneva, Switzerland (April 5th, 2006)

#johnny depp#actor#celeb#icon#john christopher depp ii#musician#ilovejohnnydepp#iloveyoujohnnydepp#mont blanc#watch fair#geneva switzerland#2006#late 2000s#2000s hollywood#2000s actors#2000s icons#2000s

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tourists explore massive blast that levelled Atlantic Canada's biggest city

HALIFAX -- The top tourist draw in Halifax at this time of year has to be its sprawling waterfront boardwalk, which features some of the city's best restaurants, shops and galleries. At one end of the picturesque two-kilometre walkway, you'll find Casino Nova Scotia, and at the other, the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21.

For history buffs, however, the main attraction this year is at the midway point, inside the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

The museum, perhaps best known for its Titanic exhibit, recently opened an expanded display of stories and artifacts commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion.

It was the worst man-made disaster in Canadian history, and its anniversary is being marked in multiple ways in the city, where visitors can find multiple relics and commemorations.

The massive blast, just after 9 a.m. on Dec. 6, 1917, was caused by the collision of a Belgian relief ship and a French munitions vessel carrying TNT through the narrowest part of the harbour.

Entire neighbourhoods were levelled by the resulting shock wave and tsunami. More than 1,600 homes and businesses were destroyed, many of them burning to the ground after their coal stoves tipped over. Windows were broken as far away as Truro, about 100 kilometres away. And the ground shook in P.E.I.

Almost 2,000 people were killed. Another 9,000 were injured, hundreds of them blinded by flying glass.

The maritime museum's latest exhibit is called "Collision in the Narrows." Among other things, it includes twisted metal fragments that were hurled across the city, including a piece of the SS Mont Blanc's rudder hinge, which weighs several hundred kilograms.

The items mostly come from the museum's collection of explosion artifacts, which is still growing 100 years later.

"Every year in the springtime, the frost heaves up pieces of the Mont Blanc," says Roger Marsters, curator of marine history. "We get new offers of donations every year."

To be sure, the city's north end is still marked by the explosion.

Every year on Dec. 6, a memorial ceremony is held at the Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower at Fort Needham, which overlooks the area devastated by the blast.

Craig Walkington, chairman of the Halifax Explosion anniversary advisory committee, says this year's ceremony will pay tribute to those who survived the explosion. Earlier this year, the city issued an invitation to those who survived the blast to come forward for recognition.

At least 18 people, including a 105-year-old woman, have responded to the call, though little is known about who they are, Walkington said.

"We want to recognize those who were alive at the time of the explosion, and hopefully be able to find someone who can actually talk about their own personal memories," Walkington said in an interview.

Not far from the bell tower, which is being refurbished, is the Hydrostone, one of the most tangible legacies of the disaster, known these days for its charming restaurants, shops and cafes. The unusual neighbourhood was built after the explosion in only 10 months.

It includes 324 dwellings -- mostly row houses, some duplexes and a few detached homes -- designed by Montreal architect George Ross. All of the homes are made from tough, fireproof concrete blocks meant to look like cut granite, a welcome feature for tenants who had seen so many wood-frame homes burn to the ground.

The area is also notable for its short, parallel, one-way streets and back lanes. But its most distinctive feature is the wide, grassy boulevards in front of each row of homes.

Other evidence of the explosion is littered across the city.

More than three kilometres from the blast site, in the middle of a residential neighbourhood on Spinnaker Drive, a humble monument provides mute testimony to the incredible power of the explosion. A 500 kilogram hunk of metal -- the shaft from the anchor of the Mont Blanc -- sits atop a granite pedestal in a small, tree-lined park.

Across the harbour, in Dartmouth's north end, a similar monument features a twisted, 500-kilogram cannon from the stern of the ship. It, too, was thrown more than three kilometres.

A new website, called "100 Years 100 stories" (http://ift.tt/2uldPNo), includes an interactive map that shows the various memorials and exhibits across the city.

The website has become a clearing house for all of the events and locations associated with the upcoming anniversary. It also includes stunning archival photos and heartbreaking stories from that grim time.

A grainy 13-minute film shows flattened homes, relief workers trudging through the snow, shattered windows, mangled factories, and wounded people being carried on stretchers to be treated in railway cars.

One of the most touching photos is that of 23-month-old Annie Welsh, who was found in a burned-out home, sheltered by the ash pan of a stove. She would later become known as Ashpan Annie, a well-known resident of Halifax who died at the age of 95 in 2010.

from CTV News - Atlantic http://ift.tt/2vIRbSK

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How the Halifax Explosion led to the creation of the CNIB

The Halifax Explosion claimed thousands of lives, but it also altered the lives of hundreds of others, many of whom lost their sight in the blast.

The tragedy remains the largest mass-blinding incident in Canadian history and led to the creation of the Canadian National Institute for the Blind.

As people pressed their faces to their windows, curious about the flames erupting aboard SS Mont Blanc in Halifax Harbour, they had no idea it would be the last sight they would ever see.

“Many of the people who were blinded were actually, it was because they got shards of glass from the window in their eyes,” explains Jane Beaumont, an archivist for the CNIB.

Roughly 2,000 people were killed when the munitions vessel SS Mont Blanc collided with the SS Imo in Halifax harbour on Dec. 6, 1917. Thirty-seven people were blinded, more than 1,000 eyes were treated for eye injuries, and a couple hundred more had to have their eyes removed.

“I try to imagine instantaneous change in your life when you lose your sight in an accident, the trauma of the explosion, what’s happened to the rest of your family,” says Beaumont. “Perhaps your husband was at work and he’s gone missing, or your husband is in the trenches in Europe.”

She also points out that there were no social services or supports available for victims at that time.

“Adults before this time had very, very few resources, and if they were, if they didn’t have private resources, they were pretty much destined to poverty,” says Beaumont.

As the first province to legislate education for the blind, Nova Scotia was already known for its progressive policy for the blind and visually impaired. However, the Halifax School for the Blind was only for children, and with hundreds of people affected by the Halifax Explosion, and more veterans returning home blinded from battle, there was a need to help adults.

The principal of the school lost his own sight as a teenager, so he understood the challenge of losing one’s sight and adapting to a new life. The son of a doctor from Windsor, N.S., Charles Frederick Fraser was educated at the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts. He would draw on those contacts and their skills to help in the wake of the Halifax Explosion.

“He was a tireless advocate for people who were blinded and he believed that people who had lost their sight or had low vision could lead useful lives and should be given all the tools they need to do that, which wasn’t necessarily the attitude in the rest of the country or the world in general,” says Beaumont.

Fraser helped create the first CNIB, which will mark its 100th anniversary of service next year, on the heels of the 100th anniversary of the disaster that led to the creation of the organization.

With files from CTV Atlantic's Marie Adsett

from CTV News - Atlantic http://ift.tt/2lYa28X

0 notes

Text

Upgrades for commemorative park ahead of Halifax Explosion anniversary

Fort Needham Park is a place where the devastation of the Halifax explosion is permanently remembered and now it’s undergoing a 2.7 million upgrade.

Renovations to the 75-year-old park are scheduled to be completed in time for this year’s commemoration of the explosion’s 100th anniversary.

“There’s still a lot of work left to do, but is coming together fast,” says construction project manager, Jeff Spares.

Bells at the park still ring every hour despite the construction happening around them, but a lot has changed.

Certain areas of the park are closed to the public except for 20 to 30 construction employees who are on the site each day.

The park was designed with specific aspects of the explosion in mind to shed light on particular events that occurred throughout Halifax’s history.

“So this ship wall here represents the Mont Blanc and is constructed to match the exact length of the Mont Blanc ship,” says Spares.

Some of the upgrades include a walk through time – a path lined with a wall that’s the length of two ships, Mont Blanc on one side and Imo on the other.

“This is the Vince Coleman message that he had sent to stop the trains from entering Halifax and this has been transcribed into the wall into Morse code."

Spares says despite it being the centennial anniversary of the explosion, it was also about time the park got a makeover and it’s a way for the park to start over again.

“The playground was old and tired, the memorial bell tower, the lighting was at the end of its life, and in anticipation of the 100th anniversary it was time for a total park refresh,” he says.

Spares says his favourite aspect of the park is the Richmond staircase that runs from Union Street up to the bell tower.

“During the Halifax explosion the community of Richmond was devastated so we've etched the word Richmond into the staircase.”

The names of schools and institutions that were lost in the devastation have been engraved in the railings on the vertical posts attached to the stairs.

The park’s playground has been replaced and the sports field has been updated.

Soon, there will be a wall at the memorial park with the dates 1917 and 2017.

Historian, Blair Beed says he's glad something is being done to mark 100 years.

“It’s an interesting visual,” Beed says. “Of course as a neighbourhood park some people are reticent because it's sort of organically formed, with a rose garden and a football spot, it’s been formulated into a vision and we'll see what the vision ends up being.”

The project has been three or four years in the making and Spares expects it will be completed by Dec. 6.

With files from CTV Atlantic’s Laura Brown.

from CTV News - Atlantic http://ift.tt/2hl4aSI

0 notes

Text

Play highlights racial tensions during Halifax Explosion on 100th anniversary

HALIFAX -- When Lisa Nasson was a young girl growing up on a reserve in Nova Scotia, she learned about the disastrous Halifax Explosion at school -- but its decimating impact on the local Indigenous community was never mentioned.

Years later, the Mi'kmaq actor learned of the destruction of the Turtle Grove Mi'kmaq settlement, which was nestled on the harbour shoreline across from where the munitions vessel SS Mont Blanc collided with the SS Imo, causing a massive blast that devastated the city.

"If I had known there were people like me affected by something so tragic, I would have been able to relate more to the story of the Halifax Explosion," said Nasson, who grew up on Millbrook First Nation, about an hour's drive north of Halifax.

The experiences of Indigenous Peoples and African Nova Scotians on and after Dec. 6, 1917, have been historically underrepresented, although both communities suffered in the aftermath of the wartime explosion that killed 2,000, injured 9,000 and left 25,000 homeless.

A new play seeks to tell those stories ahead of the disaster's 100th anniversary, and although the plot of "Lullaby: Inside The Halifax Explosion" is fictitious, the play's themes about race are not, said Koumbie, the play's director.

"It highlights the racial tensions at that time," Koumbie said during a recent rehearsal. "These characters talk about their backgrounds, their religion and their upbringing."

"Representation is important. We have centuries of seeing a predominantly white male narrative be told over and over again. I think people are tired of being left out ... We learn from our art and from our media and so we need to use that to learn about ourselves and each other."

At least six families were living at Turtle Grove when the Imo, a Norwegian ship bound for Belgium, collided with the Mont Blanc, a French vessel carrying explosive chemicals and ammunition. The resulting blast and tsunami razed Turtle Grove, killing at least nine of its residents and thousands of others in the surrounding area.

Africville was a black community near the Halifax neighbourhood of Richmond -- the hardest hit area in the city's north end.

"Relief efforts that came through the city went right through Africville, but none of that was given to Africville," said Troy Adams, who plays Edward in the play. "These are the types of things many people are not aware of."

Roger Marsters, curator of marine history at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, said the experiences of marginalized communities have been overlooked, in part because historical documentation was not preserved.

"They were not deemed sufficiently important by mainstream society at the time, and as a result, the documentation to tell the stories of other communities just doesn't exist," Marsters said.

"These are important elements of the story that have been almost completely ignored," he said. "If we want to fully and completely understand the impacts of the blast both in 1917 and its continuing legacies today, we need to tell those stories. Without them, we don't understand the blast and its consequences."

"Lullaby: Inside The Halifax Explosion," written by Karen Bassett, follows a black man (Adams), a teenage Mi'kmaq girl (Nasson) and a white woman (Mauralea Austin) in the moments after the explosion.

The play has already been performed before about 30 schools in Nova Scotia. It begins a tour of Nova Scotia theatres on Saturday at Bauer Theatre in Antigonish, N.S., before heading to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax on Nov. 22 for a three-week run.

from CTV News - Atlantic http://ift.tt/2gNiGWe

0 notes