#Musselburgh fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Stigmaria Fossil Stem Carboniferous Coal Measures Scotland UK | Musselburgh Plant Fossil with Certificate

This listing is for a beautifully preserved Stigmaria fossil stem, originating from the Carboniferous Period, specifically the Coal Measures of Musselburgh, near Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. This is a genuine piece of ancient plant life from approximately 310–300 million years ago, dating to the late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) sub-period.

The fossil shown in the photos is the exact specimen you will receive. It has been carefully selected for its distinct features and natural history significance, making it ideal for collectors, educators, and anyone interested in palaeobotany.

Geological & Palaeontological Details:

Fossil Type: Root/stem structure (rhizomorph) of an ancient lycopsid plant

Genus: Stigmaria (likely belonging to the root system of Lepidodendron or Sigillaria)

Order: Lepidodendrales

Geological Period: Carboniferous

Stage: Pennsylvanian (Westphalian)

Stratigraphy: Coal Measures (part of the Scottish Coal Measures Group)

Location: Musselburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

Depositional Environment: Low-lying equatorial swamp and floodplain environments where dense lycopod forests flourished. These environments formed the organic-rich layers that eventually transformed into coal seams.

Morphology & Features:

Stigmaria is characterised by a cylindrical, branching root structure with spirally arranged rootlet scars, forming the distinctive pitted pattern seen on the fossil’s surface

The preserved features show clear detail of the rootlet attachment points that supported anchorage in soft, waterlogged substrates

Typically preserved in grey shale or siltstone, reflecting anoxic burial conditions ideal for fossilisation

Provides key insights into the rooting systems of Carboniferous lycopod trees, the dominant flora of ancient coal-forming forests

Notability: Stigmaria fossils are among the most iconic plant fossils of the Carboniferous. Their distinct morphology and association with Lepidodendron and Sigillaria make them critical to understanding the ecology and evolution of the Earth’s earliest forested ecosystems. This specimen, from the historically significant coalfields near Musselburgh, represents a rare and regionally important find.

Additional Details:

All our fossils are 100% genuine specimens

Includes a Certificate of Authenticity

Photo shows the exact fossil for sale

Scale cube = 1cm – please refer to photos for precise sizing

Whether for education, research, or private display, this specimen offers a tangible connection to the lush primeval landscapes that once covered prehistoric Scotland. A perfect addition to any fossil or palaeobotanical collection.

#Stigmaria#plant fossil#Carboniferous fossil#Coal Measures#fossil stem#root fossil#Lepidodendron root#Musselburgh fossil#Edinburgh fossil#Scottish fossil#UK plant fossil#genuine fossil#fossil with certificate#fossil roots#Carboniferous flora#Stigmaria fossil stem#ancient plant fossil#fossilised roots#fossil collector specimen#Stigmaria rhizome

0 notes

Text

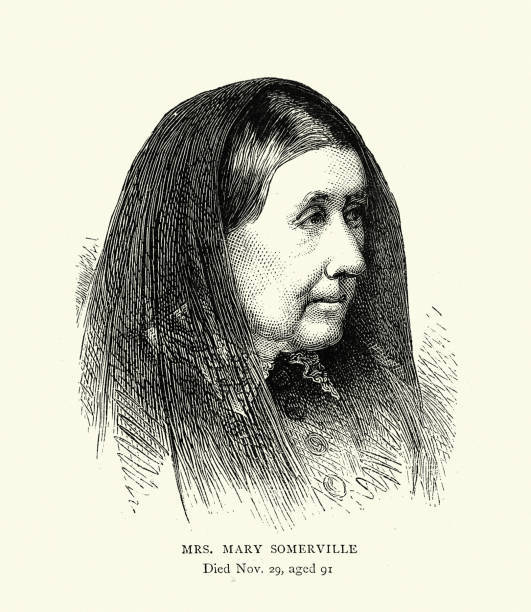

The Scottish Polymath Mary Somerville died on November 28th 1872 in Naples.

Today Somerville’s name lives on in an Oxford college, but her wider legacy is largely forgotten. She is the face of the Royal Bank of Scotland’s £10 banknote – the first non-royal woman to be honoured in this way.

Born in Mary Fairfax, Jedburgh on 26th December, 1790, Somerville grew up in the Fife seaside town of Burntisland. She was fascinated by the natural world from the start, collecting shells and fossils, and observing birds and sea creatures.

When her father returned from the sea, he discovered 8- or 9-year-old Mary could neither read nor do simple sums. He sent her to an elite boarding school, across the Firth of Forth, Miss Primrose's School in Musselburgh.

Miss Primrose was not a good experience for Mary and she was sent home in just a year. She began to educate herself, taking music and painting lessons, instructions in handwriting and arithmetic. She learned to read French, Latin, and Greek largely on her own. At age 15, Mary noticed some algebraic formulas used as decoration in a fashion magazine, and on her own she began to study algebra to make sense of them. She surreptitiously obtained a copy of Euclid's "Elements of Geometry" over her parents' opposition.

Four years after marrying, Mary Somerville and her family moved to London. Their social circle included the leading scientific and literary lights of the day, including Ada Bryon and her mother Maria Edgeworth, George Airy, John and William Herschel, George Peacock, and Charles Babbage. Mary and William had three daughters and a son who died in infancy. They also traveled extensively in Europe.

In 1826, Somerville began publishing papers on scientific subjects based on her own research. After 1831, she began writing about the ideas and work of other scientists as well. One book, "The Connection of the Physical Sciences," contained discussion of a hypothetical planet that might be affecting the orbit of Uranus. That prompted John Couch Adams to search for the planet Neptune, for which is he is credited as a co-discoverer.

Mary Somerville's translation and expansion of Pierre Laplace's "Celestial Mechanics" in 1831 won her acclaim and success: that same year, British prime minister Robert Peel awarded her a civil pension of 200 pounds annually. In 1833, Somerville and Caroline Herschel were named honorary members of the Royal Astronomical Society, the first time women had earned that recognition. Prime Minister Melbourne increased her salary to 300 pounds in 1837. William Somerville's health deteriorated and in 1838 the couple moved to Naples, Italy. She stayed there most of the remainder of her life, working and publishing.

In 1848, Mary Somerville published "Physical Geography," a book used for 50 years in schools and universities; although at the same time, it attracted a sermon against it in York Cathedral.

William Somerville died in 1860. In 1869, Mary Somerville published yet another major work, was awarded a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society, and was elected to the American Philosophical Society.

By 1871, Mary Somerville had outlived her husbands, a daughter, and all of her sons: she wrote, "Few of my early friends now remain—I am nearly left alone." Mary Somerville died in Naples on November 29, 1872, just before turning 92. She had been working on another mathematical article at the time and regularly read about higher algebra and solved problems each day.

Her daughter published "Personal Recollections of Mary Somerville" the next year, parts of a work which Mary Somerville had completed most of before her death.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foraging for a more sustainable world

* This post was written as part of my assessed coursework for Responding to Sustainability Challenges: Critical Debates. It was written on October 1st 2020 *

My challenge is to identify more than human life within my locality and to forage one of these a week to include in a meal. I will focus my search in my garden, at the River Esk and the Musselburgh coast.

I am resistant towards making individual lifestyle changes. I feel the mainstream focus on straws and light switches shifts blame from states and corporations to those relatively less powerful and more constrained by wider rules, systems and levels of access. It shows, as Maniates (2001:33) says, “capitalism’s ability to commodify dissent” which limits our capacity to imagine meaningful responses that live up to the challenge at hand. Therefore, my first thought was to engage in public sphere actions where I can have more influence as part of a community.

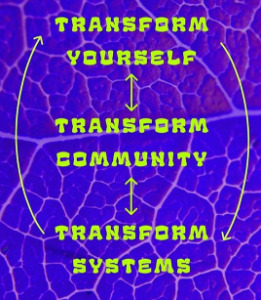

I thought of reflecting on my work with Climate Camp Scotland, a direct action group working against the fossil fuel industry in Scotland and for a Just Transition for workers and communities across the world. A Just Transition is a concept referring to a deliberate effort to prepare for a transition away from carbon economies and to promote socially sustainable jobs (Smith, 2017). The work I do in the group is building conflict processes based within a Transformative Justice (TJ) framework. TJ is a liberatory political approach to different levels of harm that centres safety and healing for survivors, does not rely on state interventions, and seeks to transform the conditions and people that cause harm (Mingus, 2018). I see this as part of social sustainability. Where organising spaces can be emotionally gruelling, risky and force us to confront uncomfortable topics, working on this interpersonal level is important in sustaining public sphere work. TJ has taught me that systems of violence are felt and enacted by each of us; that they seep into our lives. Is this the case with our relationships to the earth? Does that impact how we engage in solution making? What will a Just Transition from ecologically destructive industries look like if we hold an ambivalent relationship to nature?

Image by @ chiara.acu on Instagram

These questions drew me to this challenge. Malm (2013) discusses how fossil fuel production changed time-labour dynamics, throwing them out of sync with earth cycles and into sync with the drive for profit. It feels as though most of our waking hours are directed by demands of our employers, leaving us little time to think of what food we put in our mouths and how to care for our loved ones. Nevermind having the time to know nature. Before lockdown, I only walked back and forth on the same route to the bus stop. During lockdown, I was able to explore. I couldn’t name any of the plants. What I thought were dock leaves weren’t; what I thought were elderberry, were common ivy. This vast disconnect became so clear. Why am I spending hours in meetings and at protests if it is not to retain, rebuild and transform our relationship to each other and the earth?

I hope that naming and eating foods from my locality will help me tend a relationship with my environment rather than being insulated from it. I hope it directs me to taking effective public sphere action by letting me see not only what I am fighting against, but how to transform the conditions that allow the climate crises by healing my relationship to earth.

References

Image by @chiara.acu

Malm, A. 2013, 'The Origins of Fossil Capital: From Water to Steam in the British Cotton Industry’, Historical Materialism, 21(1), 15-68

Maniates, M. 2001, ‘Individualisation: Plant a Tree, Buy a Bike, Save the World?”, Global Environmental Politics, 1(3), 31-50

Mingus, M. 2018, ‘Transformative Justice: A Brief Introduction’, Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective [online], Available at: https://transformharm.org/transformative-justice-a-brief-description/

#foraging#scotland#transformative justice#just transition#plant healing#climate justice#environmentalism

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Scottish Polymath Mary Somerville died on November 28th 1872 in Naples.

Today Somerville’s name lives on in an Oxford college, but her wider legacy is largely forgotten. She is the face of the Royal Bank of Scotland’s £10 banknote – the first non-royal woman to be honoured in this way.

Born in Mary Fairfax, Jedburgh on 26th December, 1790, Somerville grew up in the Fife seaside town of Burntisland. She was fascinated by the natural world from the start, collecting shells and fossils, and observing birds and sea creatures.

When her father returned from the sea, he discovered 8- or 9-year-old Mary could neither read nor do simple sums. He sent her to an elite boarding school, across the Firth of Forth, Miss Primrose's School in Musselburgh.

Miss Primrose was not a good experience for Mary and she was sent home in just a year. She began to educate herself, taking music and painting lessons, instructions in handwriting and arithmetic. She learned to read French, Latin, and Greek largely on her own. At age 15, Mary noticed some algebraic formulas used as decoration in a fashion magazine, and on her own she began to study algebra to make sense of them. She surreptitiously obtained a copy of Euclid's "Elements of Geometry" over her parents' opposition.

Four years after marrying, Mary Somerville and her family moved to London. Their social circle included the leading scientific and literary lights of the day, including Ada Bryon and her mother Maria Edgeworth, George Airy, John and William Herschel, George Peacock, and Charles Babbage. Mary and William had three daughters and a son who died in infancy. They also traveled extensively in Europe.

In 1826, Somerville began publishing papers on scientific subjects based on her own research. After 1831, she began writing about the ideas and work of other scientists as well. One book, "The Connection of the Physical Sciences," contained discussion of a hypothetical planet that might be affecting the orbit of Uranus. That prompted John Couch Adams to search for the planet Neptune, for which is he is credited as a co-discoverer.

Mary Somerville's translation and expansion of Pierre Laplace's "Celestial Mechanics" in 1831 won her acclaim and success: that same year, British prime minister Robert Peel awarded her a civil pension of 200 pounds annually. In 1833, Somerville and Caroline Herschel were named honorary members of the Royal Astronomical Society, the first time women had earned that recognition. Prime Minister Melbourne increased her salary to 300 pounds in 1837. William Somerville's health deteriorated and in 1838 the couple moved to Naples, Italy. She stayed there most of the remainder of her life, working and publishing.

In 1848, Mary Somerville published "Physical Geography," a book used for 50 years in schools and universities; although at the same time, it attracted a sermon against it in York Cathedral.

William Somerville died in 1860. In 1869, Mary Somerville published yet another major work, was awarded a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society, and was elected to the American Philosophical Society.

By 1871, Mary Somerville had outlived her husbands, a daughter, and all of her sons: she wrote, "Few of my early friends now remain—I am nearly left alone." Mary Somerville died in Naples on November 29, 1872, just before turning 92. She had been working on another mathematical article at the time and regularly read about higher algebra and solved problems each day.

Her daughter published "Personal Recollections of Mary Somerville" the next year, parts of a work which Mary Somerville had completed most of before her death.

40 notes

·

View notes