#Norman Conquest Coin Hoard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

1,000-Year-Old Norman Conquest Coin Hoard Sells for $5.6 Million

A hoard of Norman-era silver coins unearthed five years ago in southwestern England has become Britain’s most valuable treasure find ever, after it was bought for £4.3 million ($5.6 million) by a local heritage trust.

For the group of seven metal detectorists who discovered the 2,584 silver pennies in the Chew Valley area, about 11 miles south of the city of Bristol, it marks a lucrative windfall since they will pocket half that sum. The landowner on whose property the coins were found will receive the other half.

According to South West Heritage Trust, the body that acquired them, the coins date from around 1066-1068, spanning one of the most turbulent periods in English history as the country was successfully invaded for the last time during the Norman Conquest.

One coin, the oldest in the hoard, depicts King Edward the Confessor, who died childless in January 1066, triggering a period of instability since he had promised the throne to three claimants: Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex; Harald Hardrada, King of Norway; and William, Duke of Normandy.

Edward named Harold Godwinson as his successor on his deathbed, but the newly crowned King Harold II faced challenges from the other two claimants to the throne, and he was eventually defeated by William at the Battle of Hastings in October 1066.

The hoard of coins depicts this turmoil as Harold II features on just under half of them while William I (also known as William the Conqueror) features on the rest.

“It comes from a turning point in English history and it encapsulates the change from Saxon to Norman rule,” Amal Khreisheh, curator of archaeology at South West Heritage Trust, said in a video on the organization’s website.

“The hoard was buried in around 1067-1068 on an estate in Chew Valley which later belonged to Giso, the Bishop of Wells. We think it was probably buried for safekeeping during the time of rebellions against William in the South West.

“We know that in 1068, the people of Exeter rebelled against William. At around this time, Harold’s sons returned from exile in Ireland and their forces mounted attacks around the River Avon and then down into Somerset and the Chew Valley,” Khreisheh added.

Finding coins that were in use almost 1,000 years ago is exceptionally rare – this hoard contains twice as many coins from during Harold II’s reign as had previously been found.

The coins will now go on public display at the British Museum in London from November 26, before heading back to museums in southwest England.

#1000-Year-Old Norman Conquest Coin Hoard Sells for $5.6 Million#Norman Conquest Coin Hoard#Norman Conquest#King Edward the Confessor#King Harold II#William Duke of Normand#William the Conqueror#treasure#silver#silver coins#collectable coins#metal detector#metal detecting finds#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A farmer uncovered a rare hoard of 1,000-year-old silver coins in a southwest England field, with a total value of $5.6 million.

The 2,584 coins, featuring both King William I and his predecessor Harold II, were buried during the aftermath of the Norman Conquest.

This discovery is being hailed as one of the most significant in recent years, offering fresh insight into the complex history surrounding the 1066 invasion. After being displayed at the British Museum, the coins will find a permanent home in Somerset.

Read more at link in our bio.

0 notes

Text

Hoard of silver coins dating from Norman Conquest is Britain’s most valuable treasure find ever😳🫢😰👏🏼👍🏻🙏🏼

0 notes

Photo

Huge Anglo-Norman coin hoard discovered in England A massive hoard of over 2500 coins dating back to the eleventh-century has been discovered in southwestern England. It represents the largest discovery of coins from the period following the Norman Conquest in 1066, and preliminary estimates are valuing the hoard at £5 million.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Coin Hoard Offers Evidence of Early Tax Evasion

https://sciencespies.com/history/medieval-coin-hoard-offers-evidence-of-early-tax-evasion/

Medieval Coin Hoard Offers Evidence of Early Tax Evasion

Shortly after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, a wealthy local buried a trove of 2,528 coins in what is now Somerset, England. Featuring the likenesses of both Harold II—the country’s last crowned Anglo-Saxon king—and his successor, William the Conqueror, the hoard is the largest collection of post-Norman Conquest coins found to date. But that’s not all: As the British Museum reports, the medieval money also represents an early example of the seemingly modern practice of tax evasion.

According to a press release from the museum, three of the silver pieces are “mules,” or illegally crafted coins boasting designs from mismatched dies on either side. Two boast Harold’s image on one side and William’s on the other, while the third depicts William and Harold’s predecessor, Edward the Confessor. By re-using an outdated die, the moneyer who made the coins avoided paying taxes on new dies. Per the Guardian’s Mark Brown, the two-faced coin would have been easy to present as legal currency, as most Anglo-Saxons were illiterate and unable to distinguish between the relatively generic royal portraits.

“One of the big debates amongst historians is the extent to which there was continuity or change, both in the years immediately after the Conquest and across a longer period,” Gareth Williams, the British Museum’s curator of early medieval coinage, says in the statement. “Surviving historical sources tend to focus on the top level of society, and the coins are also symbols of authority and power. At the same time, they were used on a regular basis by both rich and poor, so the coins help us understand how changes under Norman rule impacted on society as a whole.”

A mule bearing Edward the Confessor’s image

(Pippa Pearce/© The Trustees of the British Museum)

More

Adam Staples, one of the metal detector enthusiasts who helped unearth the trove, tells Brown that he and partner Lisa Grace were teaching friends how to use the treasure-hunting tool when one member of their party happened upon a silver William coin. Staples calls it “an amazing find in its own right.” But then, there was another signal pointing to another coin. Suddenly, he says, “there were beeps everywhere, [and] it took four or five hours to dig them all up.”

The Telegraph’s Hannah Furness writes that the total value of the find could be upward of £5 million (just over $6 million). However, considering the coins’ condition and potential flooding of the market if the hoard is offered for sale, that value may be overinflated.

For now, the hoard is under the care of the British Museum, which will determine whether it falls under the legal category of “treasure.” (Under the Treasure Act of 1996, individuals in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are required to report finds to their local coroner, who then initiates an investigation.) If the pieces are classified as treasure, the Roman Baths and Pump Room, fittingly located in Bath, has expressed interest in acquiring them.

The coins depict Edward the Confessor, Harold II and William the Conqueror

(Pippa Pearce/© The Trustees of the British Museum)

More

According to the British Museum, the collection contains 1,236 coins bearing Harold’s likeness, 1,310 coins testifying to William’s takeover and various silver fragments. In total, the newly discovered Harold coins outnumber the collective amount known to exist previously by almost double. The William coins, meanwhile, represent more than five times the number of previously recovered pieces issued by the Norman king following his coronation in 1066.

Writing for the Conversation, Tom Licence of England’s University of East Anglia explains that the hoard—sizable enough to pay for an entire army or, alternatively, around 500 sheep—was likely hidden by a member of the nobility hoping to protect his wealth amid a volatile political environment. (Harold ascended to the throne after the death of his childless brother-in-law, Edward the Confessor, but William of Normandy, later William the Conqueror, disputed the king’s claim and soon seized power.)

It remains unclear which of these regimes the aristocrat in question supported, but as Gareth Williams, the British Museum’s curator of early medieval coinage, points out in an interview with the Guardian’s Brown, the key detail is that the person was burying the hoard during a period of instability. He adds, “It is the sort of circumstances in which anyone might choose to bury their money.”

Like this article?

Join us on Facebook or Twitter for a regular update.

#History

0 notes

Text

Huge hoard of Norman coins reveals medieval tax scam | Culture

Huge hoard of Norman coins reveals medieval tax scam | Culture

[ad_1]

A millennium-old tax scam has been revealed with the discovery of thousands of coins in a muddy field that together make up the largest hoard to be unearthed from the immediate post-Norman conquest period.

The British Museumannounced the discovery of the coins from a pivotal moment in English history on Wednesday. Some depict Harold II, the last crowned Anglo-Saxon king of England, and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Rare gold penny in Heritage sale

English super-rarity: the superbly struck 761-year-old gold penny of Henry III that will be offered by Heritage Auctions in January with a grade of MS-63 NGC. (Images courtesy www.ha.com)

Few English coins are as desired as the gold pence of Henry III. Heritage Auctions will be offering an example as part of their NYINC sale in January. And it is not just any 761-year-old Henry III gold penny (S-1376). This one comes graded MS-63 by Numismatic Guaranty Corporation and with a superb provenance.

The penny of 1257 was the first English hammered gold coin struck since the Norman Conquest. It was produced at a time when Henry’s rule was becoming increasingly unpopular. Among other matters, a series of foreign adventures had ended in costly disasters.

One such adventure in 1254 had cost the king a hoard of 2,000 marks of gold. In 1257, accrued debts required him to cash in a second stash. Rather than selling quickly, which could have depressed the gold price, Henry opted to follow the lead of several Italian cities and convert his gold to pennies. London moneyer William of Gloucester was charged with production of these coins.

Unlike the current silver pennies, the obverse showed a full-length figure of King Henry crowned, robed, and seated on his throne. His right hand bears his scepter and his left an orb. About is the inscription HENRIC REX : I.I.I : This design is similar to that of a silver penny of Edward The Confessor (S-1181), who Henry took as his role model.

The reverse features the long cross style introduced by the king for his silver coinage in 1247. The pellets in each angle are reduced in size compared with the silver and a large rose placed between them. The legend gives the moneyer’s name and mint location as WILLEM : ON LVNDEN [William at London].

Each penny was struck on a 22 mm, .995 fine gold flan of 45.2 grains (2.929 grams), i.e. twice the weight of a silver penny. With an exchange rate of 10:1 between gold and silver, the new coins were to be current at 20 pence.

Records show William delivered 37,280 gold pennies valued at 466 marks on Aug. 27, 1257. A further 15,200 worth 190 marks were completed by October the following year.

However, the new coins did not find favor among London’s merchants. For starters, each represented a comparatively large sum of money and hence held little interest for the majority of the population. Secondly, there was concern that if gold became readily available throughout the kingdom, its price could be depressed. Thirdly, the gold coins were perceived as undervalued with respect to silver such they were worth more in the melting pot than the marketplace.

The merchants petitioned the king against having to accept them. Henry responded by issuing a proclamation on Nov. 24 stating no one was obliged to accept his gold pennies and any could be returned to the royal exchange where the bearer would receive the current rate in silver coin – less a halfpenny transaction fee.

This had little effect on the coins’ acceptability. The 2.5 percent fee was disincentive to any canny merchant thinking of cashing them in. Eventually they were recalled, with Henry even paying 24 pence apiece for late arrivals between 1265 and 1270.

A number of the returned coins were used by Henry as Church votive offerings. Two of the known examples surfaced in Italy and may well have been gifted to the Pope.

From 1270 on, the coins effectively dropped from sight for 500 years until recognized by British numismatists in the 18th century.

The number cited as extant has varied from six to eight. Most recently, Lord Stewartby in his 2009 work “English Coins 1180-1551,” states “Seven coins are recorded, from four pairs of dies.” Three of these are unique. Obvious differences are in the beading on the throne and in the arrangement and wording of the reverse legend. London may be given as LVND or LVNDE.

If a hammered gold rarity is not your coin of choice, the Heritage NYINC sale offers much much more. For the ancient collectors, there is one of two known gold staters of Pharnaces II of Pontus in NGC Choice AU 5/5 – 3/5. The Scots among us may be intrigued by a James VI (I of England) gold 20 pounds of 1575 struck in Edinburgh (S-5451), a nice coin in XF-40 NGC.

Or how about one of the very few Edward VIII nickel-brass pattern threepences of 1937 in MS-61 NGC (KM-849, S-4064B)? Perhaps a Napoleon franc l’an 13-A (1804) in MS-64 Professional Coin Grading Service (KM-656.1). Then there is an Alexander III gold 10 rubles of 1894 from St. Petersburg (KM-YA42) that comes in MS-64 NGC.

And that’s just the start. Full details, including estimates, are available at Heritage Auction’s website: www.ha.com.

This article was originally printed in World Coin News. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of World Coins, 1601-1700 is your guide to images, prices and information on coins from so long ago.

• More than 600 issuing locations are represented in the Standard Catalog of World Coins, 1701-1800 .

The post Rare gold penny in Heritage sale appeared first on Numismatic News.

0 notes

Text

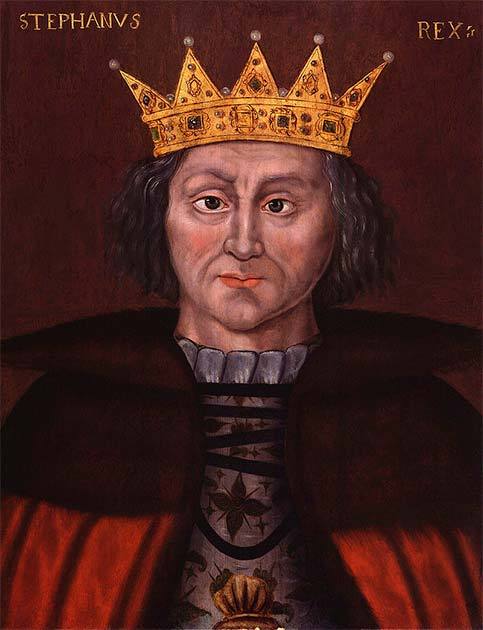

King Stephen 12th Century Rare Penny Hoard Found in England

An unnamed metal detectorist recently discovered a scarce collection of 12th-century silver pennies near the village of Wymondham in the county of Norfolk in eastern England.

This valuable cache of coins included seven pieces minted during the reign of King Stephen and two more dated to the reigns of Stephen’s successors, Henry II and III.

A grandson of William the Conqueror, Stephen took the throne on the death of King Henry I. However most of his reign was spent in a bitter civil war between him and his rival for the throne, Henry’s daughter Matilda.

The find is made up of two pennies, three cut halfpennies and two cut quarters of pennies from Stephen’s reign, as well as two cut quarters of short cross pennies from Henry II and Henry III’s reigns.

The discovery of pennies dating back to King Stephen’s reign is especially noteworthy, as these silver pieces are among the hardest to find of all medieval coins.

The Norfolk Historic Environment Service’s numismatist (coin expert) Adrian Marsden announced the discovery of this remarkable collection of rare coins.

In an interview with the BBC, expressed his opinion that the coins minted during King Stephen’s time had been carried together inside a coin purse, while the other two silver pieces had been lost separately at a later time by another individual.

“I suspect this is a purse loss because you’ve got chopped halves and quarters. With a hoard, you hide the best coins you’ve got,” Dr Marsden said.

The Norman Conquest in 1066 destroyed Anglo-Saxon England’s “very monetised and sophisticated economy… setting the country back at least 100 years,” he said.

When money was scarce in the 11th and 12th centuries, pure silver pennies were crudely chopped into pieces of varying sizes to “reinflate” the money supply (put more money in circulation). Because new coins were not being minted in large quantities during King Stephen’s 12th-century reign, the newly discovered coins are an unusual and thus valuable discovery, even in their less-than-perfect condition.

By Leman Altuntaş.

#King Stephen 12th Century Rare Penny Hoard Found in England#village of Wymondham#coins#silver coins#collectable coins#ancient artifacts#metal detecting#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#middle ages

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2019, in a farmer's field in southwest England, an amateur metal detectorist and six friends found a hoard of more than 2,500 silver coins that had been in the ground for almost 1,000 years.

The coins were valued at $5.6 million and are now bound for several British museums; they are expected to help shed light on the turbulent aftermath of the Norman conquest of England.

Read more at link in bio.

0 notes

Photo

Metal Detectorist Finds Two Rare 14th Century Gold Coins

An English metal detectorist has discovered two rare gold coins dating back to the 14th century.

As Stuart Anderson reports for the Eastern Daily Press, the treasure hunter unearthed the coins in Reepham, a small town in southwest England, in 2019. Together, both coins are worth an estimated £12,000 ($16,650) and someone “at the top of society” probably owned them.

“It seems likely that both coins went into the ground at the same time, either as part of a purse loss or as part of a concealed hoard,” the United Kingdom’s Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) notes in a statement.

One of the finds was a 23-karat gold leopard, which was minted in 1344, and the other coin was a type of noble, which was minted in 1351 or 1352. Both pieces portray Edward III, who tried to bring gold coinage to England in 1344.

The leopard coin, also known as a half florin, was only minted from January to July 1344. Though the 0.12-ounce medallion is considered valuable now, this type of currency was considered a “failure” when it was initially created because the costs of producing the coins were too high; the value given to them was also disproportionate to the cost of silver, per the statement.

According to Live Science’s Laura Geggel, Edward III introduced new coins from 1344 to 1351 to solve these issues, and craftsmen minted the 0.3-ounce noble during this period.

Both coins were relatively well preserved and only had slight scratches, likely a result of agricultural activity. If a local coroner (an independent legal authority) reviews the discoveries, then they may be classified as “treasures,” a term that “refers to bonafide, often metal artifacts that meet … specific archaeological criteria” outlined by the PAS, notes Laura Geggel for Live Science in a separate article.

In the U.K., amateur treasure hunters are required to hand their finds over to local authorities. Current guidelines define treasure relatively strictly, but as Caroline Davies reported for the Guardian last December, the U.K. government is working to expand these parameters to better protect the country’s national heritage items. Objects designated as treasure become the property of the state and may be displayed at national or local museums.

These finds were particularly notable because “hardly any have survived,” notes BBC News. The coins may help experts to understand historical changes to English currency after the Norman Conquest.

“The royal treasury might talk in terms of pounds, shillings and pence, but the physical reality was sacks of silver pennies,” archaeologist Helen Geake tells BBC News. “Then Edward III decided to reintroduce the first gold coins in England since the Anglo-Saxon era—and no-one knows why.”

Eventually, England’s government melted down most of the leopards and recast them. Once the leopard was taken out of circulation, officials replaced it with the noble, which was worth six shillings and eight pence, according to BBC News.

“Almost none [of the leopards] survived because they were all pulled back in and reminted, and this is the first time that we know of that one has been found with another coin,” Geake tells the Eastern Daily Press. “It implies that this leopard is either in circulation or being held onto by someone who thinks it is worth it, which is weird behavior.”

Scholars believe that one reason for the leopard’s uncharacteristically long circulation is that the Black Death came to England in the late 1340s and killed at least one third of the population, which would have distracted government authorities from less immediate issues like coin circulation.

“Usually, the authorities would be keen to remove a withdrawn coin as soon as possible,” but the Black Death probably prevented this from happening.

By Isis Davis-Marks

#Metal Detectorist Finds Two Rare 14th Century Gold Coins#metal detector#metal detecting finds#treasure#gold#collectable coins#23-karat gold leopard#half florin#the noble#Edward III#$$$#money

174 notes

·

View notes