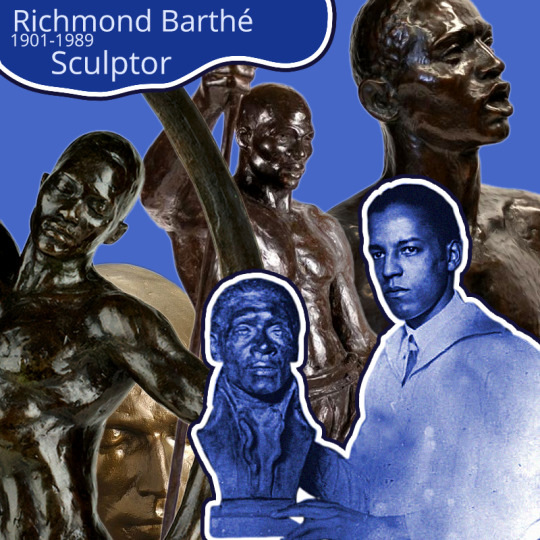

#Richmond Barthé

Text

Paul Robeson

Richmond Barthé, 1974

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

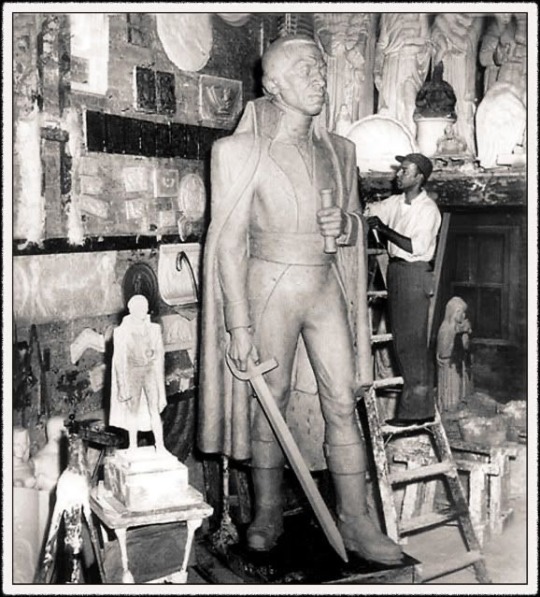

Richmond Barthé working on his Toussaint l’Ouverture sculpture (1950)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"When I was crawling on the floor, my mother gave me paper and pencil to play with. It kept me quiet while she did her errands. At six years old I started painting. A lady my mother sewed for gave me a set of watercolors. By that time, I could draw very well."

Born, James Richmond Barthé in Bay St. Louis Mississippi, he showed an interest and aptitude for the arts early.

Encouraged by his mother, family friends and educators, he continued his interest throughout his youth, exhibiting his work at the Bay St. Louis County Fair at just twelve years old.

He would unfortunately not stay in school, at the age of fourteen after a bout of typhoid fever, he withdrew from school, and when he was well again went to work instead.

The domestic work was as a houseboy for a wealthy family in New Orleans, Louisiana. While it cannot be ignored where he stood at this point in society, his move to New Orleans broadened his culture and allowed him more opportunity to see and understand art. He was introduced to a journalist for a local paper, Lyle Saxon, who tried unsuccessfully to get Richmond into a local art school.

Racism, made this an uphill battle.

But all the while, in his free time, he was still drawing.

In 1924, he donated an oil painting to a Catholic church to be auctioned at a fundraiser. So impressed by his skill, Father Harry F Kane of the Josephites raised money for Richmond to study art. And with not even a high school education, Richmond applied to schools of fine art, and was accepted to the Art Institute of Chicago.

While he is known now as a sculptor, he was largely studying painting in Chicago, and was a very talented portrait artist. He caught the attention of prominent patrons and received many handsome commissions from Chicago's black elite.

But taking an anatomy class with artist Charles Schroeder changed everything. A shift in his interest and career. Richmond had discovered his passion and turned his attentions to sculpture.

After graduating, he would move to New York City, exposing him the Harlem Renaissance at it's peak. Despite the Great Depression, this was still a vibrant time for black artists. The 1930's were some of Richmond's most prolific years.

He had a studio in Harlem briefly, but moved to the more convenient Greenwich Village, allowing him better access to dealers and collectors.

During this time, he could not initially afford to pay models, so he sought his inspiration in the world. Actors, dancers, and other artists.

In 1933 his work was inaugurated at the Rockefeller center and exhibited at the Chicago World's Fair.

The next year, he went abroad, to France with a friend of Harry F Kane.

Richmond would not be exposed to classical art and the black performers in France, even making portraits of Josephine Baker.

He would return to New York, and continue making incredible pieces. He depicted his black subjects with striking realism and incredible poise. His skill garnered him many commissions and even more praise.

In 1939 he had his largest exhibition. 18 bronze sculptures. This success would lead him to win the Guggenheim Fellowship, not once, but twice. In 1940 and 1941.

But with the 40's began World War II.

His work now, was part of war propaganda, the US Office of War Information made a film of Richmond's work. It was shown both in the US and overseas and even received a prize for his inclusion in the Artists for Victory Exhibition.

He was however, not so foolish that he took all this attention at face value. He knew this was the US's response to the Germans racist efforts abroad.

In 1947 he traveled to Haiti. He created massive sculptures of revolutionary leaders Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines. He also designed a new coins for Haiti.

Richmond would grow tired of New York and the tension in the city. He would move to Jamaica and remain there until the 1960's when violence, and the Civil Rights Movement in the US led him back again. He received much attention. His work, once again at the forefront as the Civil Rights Movement continued. He was awarded the key to the city in his home town and a large reception was given to him in New Orleans.

But it was too much, and Richmond, seeking less crowds, traveled Europe for the next five years.

Richmond never married, as he was a gay man. He did have romantic relationships but all were sadly short-lived. Tragic as his letters indicate he greatly desired a long term relationship, a "friend and lover."

In 1977, he returned to the US, settling in Pasadena California and began working on his memoirs.

He was now impoverished and age had taken it's toll on his body. He did not qualify for social security as he had always been an artist and never had a salaried job.

The irony, as outside the social security building in Washington, is a sculpture, by Richmond...

His work was still exhibited, but only occasionally and he was not earning enough to survive.

He did find respite. He befriends the actor James Garner, and Garner would come to his rescue, paying his rent and medical bulls and copyrighting Richmond's work, hiring a biographer to organize and document his work and establishing the Richmond Barthé Trust.

It is thought that a bust of Garner was Richmond's last sculpture.

Richmond Barthé would die, after years of illness March of 1989. He was eighty-eight.

Richmond's work is powerful and not only in the strong sinewy bodies of his full sculptures. His busts are personal and endowed with life, feeling so real and alive that they seem they might just breathe at any moment.

If you would like to learn more about his work and life:

Richmond Barthe Harlem Renaissance Sculptor

Richmond Barthe American Sculptor -Britannica

Richmond Barthe Biography - Encylopedia.comRichmond Barthe: A Distinguished American SculptorJames Richmond Barthe in Harlem

#Richmond Barthé#Richmond Barthe#Black Artist#Black History Month#Black Art History#Art History#American History#Gay Artist#Queer Art History

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical Indigenous Women & Figures [6]:

Queen Nanny: the leader of the 18th century Maroon community in Jamaica, she led multiple battles in guerrilla war against the British, which included freeing slaves, and raiding plantations, and then later founding the community Nanny Town. There are multiple accounts of Queen Nanny's origins, one claiming that she was of the Akan people from Ghana and escaped slavery before starting rebellions, and others that she was a free person and moved to the Blue Mountains with a community of Taino. Regardless, Queen Nanny solidified her influence among the Indigenous People of Jamaica, and is featured on a Jamaican bank note.

Karimeh Abboud: Born in Bethlehem, Palestine, Karimeh Abboud became interested in photography in 1913 after recieving a camera for her 17th birthday from her Father. Her prestige in professional photography rapidly grew and became high demand, being described as one of the "first female photographers of the Arab World", and in 1924 she described herself as "the only National Photographer".

Georgia Harris: Born to a family of traditional Catawba potters, Harris took up pottery herself, and is credited with preserving traditional Catawba pottery methods due to refusing to use more tourist friendly forms in her work, despite the traditional method being much more labour intensive. Harris spent the rest of her life preserving and passing on the traditional ways of pottery, and was a recipient of a 1997 National Heritage Fellowship awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts, which is the highest honor in the folk and traditional arts in the United States.

Nozugum: known as a folk hero of the Uyghur people, Nozugum was a historical figure in 19th century Kashgar, who joined an uprising and killed her captor before running away. While she was eventually killed after escaping, her story remains a treasured one amongst the Uyghur.

Pampenum: a Sachem of the Wangunk people in what is now called Pennsylvania, Pampenum gained ownership of her mother's land, who had previously intended to sell it to settlers. Not sharing the same plans as her mother, Pampenum attempted to keep these lands in Native control by using the colonial court system to her advantage, including forbidding her descendants from selling the land, and naming the wife of the Mohegan sachem Mahomet I as her heir. Despite that these lands were later sold, Pampenum's efforts did not go unnoticed.

Christine Quintasket: also known as "Humishima", "Mourning Dove", Quintasket was a Sylix author who is credited as being one of the first female Native American authors to write a novel featuring a female protagonist. She used her Sylix name, Humishima, as a pen name, and was inspired to become an author after reading a racist portrayal of Native Americans, & wished to refute this derogatory portrayal. Later in life, she also became active in politics, and helped her tribe to gain money that was owed them.

Rita Pitka Blumenstein: an Alaskan Yup'ik woman who's healing career started at four years old, as she was trained in traditional healing by her grandmother, and then later she became the first certified traditional doctor in Alaska and worked for the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. She later passed on her knowledge to her own daughters. February 17th is known as Rita Pitka Blumenstein day in Alaska, and in 2009 she was one of 50 women inducted into the inaugural class of the Alaska Women's Hall of Fame

Olivia Ward Bush-Banks: a mixed race woman of African American and Montaukett heritage, Banks was a well known author who was a regular contributor to the the first magazine that covered Black American culture, and wrote a column for a New York publication. She wrote of both Native American, and Black American topics and issues, and helped sculptor Richmond Barthé and writer Langston Hughes get their starts during the Harlem Renaissance. She is also credited with preserving Montaukett language and folklore due to her writing in her early career.

part [1], [2], [3], [4], [5] Transphobes & any other bigots need not reblog and are not welcome on my posts.

377 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richmond Barthé: Inner Music (Barthé was a gay sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance)

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richmond Barthé

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE FRIDAY PIC is a pair of small bronzes by Richmond Barthé: Feral Benga (1935) and Stevedore (1937) from the little survey at Michael Rosenfeld in New York.

I wrote about the show (and two others) in today's New York Times. (See the text of my Barthé piece, below).

In the Times, I argued that Barthé's work should be seen as a kind of 3D photography, presenting Black people as a "normal" part of the everyday, contemporary reality of prewar America, not needing to be dressed up in the stylish (and often primitivizing) trappings of modernist art. (Or in any of the other stereotypes African Americans were forced to embody.) What I didn't have room to point out (or claim) was that Barthé, a gay man, maybe does the same with his homoerotic images, which also normalize, maybe even naturalize, gay desire and its objects. Only a high-realist style, aligned with the illusionism of photography, had the power to do that.

And here's what I wrote about Barthé in the Times (go to the whole article to read my other two brief reviews):

Richmond Barthé, the great African American sculptor, gets kudos for his realism, but that’s faint praise that damns him: In the 1930s, when his career took off, there were hundreds of artists who had as fine a technique; there are still lots in Times Square, sculpting tourists’ faces in clay.

Looking at the 16 busts and figures in the Barthé survey at Rosenfeld — it’s curated by the British artist Isaac Julien, who has a stunning video in the Whitney Biennial — I realized that it’s best to ignore technique and to think of them as three-dimensional photographs, or as much as you possibly could before the age of 3-D scanners. The sculptures look forward to our technology, not backward at traditional realism.

The best of Barthés’s figures make his Black sitters as directly available as possible to our eyes, the way a photo seems to. There’s no interfering dose of modernist style, which was imbued with stereotypes about Blackness and “primitive” African art that invoked ideas of the “savage” and the “primeval,” or, calling on an opposite set of clichés, of the “Edenic” and “authentic.” Those were applied to African Americans in Barthé’s era, forcing them into cultural pigeonholes.

He gives his subjects more room to breathe.

“African Woman,” from 1935, shows someone whose hairdo may distance her from 1930s America, but she’s not exotic or ancestral. She’s another person of today who happens to come from far away.

The male head in “The Negro Looks Ahead” enacts its title by just being there and looking out onto the world.

Three portraits of Black boys are just three children waiting to grow up, into a world they still imagine might treat them fairly.

6 notes

·

View notes

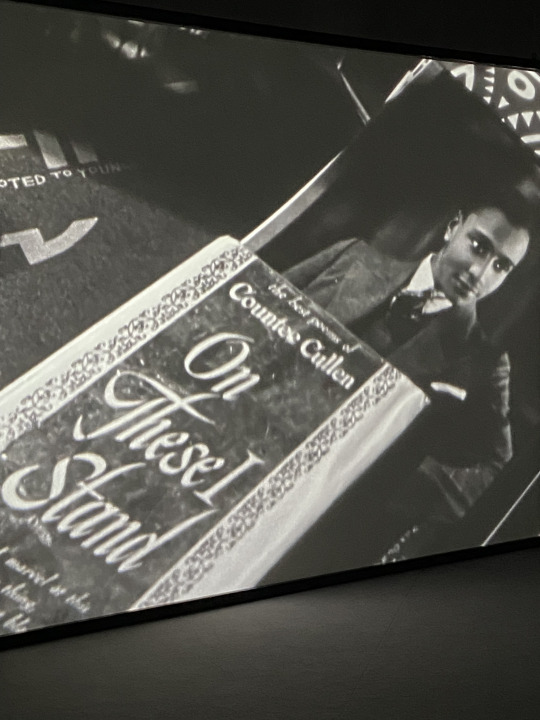

Video

I was really taken by Isaac Julien’s latest film “Once Again...(Statues Never Die)” featured an exhibit dedicated to him a Tate Britain. In a simple room with grey carpet and mirrored walls, the black-and-white film was cast on a multiple screens in a way that didn’t feel gimmicky but enhanced the sensuousness of the viewing experience, allowing us to move through the room and see the film from different angles, enacting--through our very participation--the erotics of looking that museum/studio spaces can provide, as in the cruising we see in scenes between Alain Locke (André Holland) and Richmond Barthé (Devon Terrell). Its meditations on beauty, desire, queerness, and the vexed and complex relationship between African and African-American art, the museum and the archive appealed to me deeply. It felt so fortuitous to see Barthé portrayed as well as one of his sculptures (the Black Madonna above) as I had been working on a longer poem about my relationship to him and his art all year, which I had just sent off to a journal. I might go back and see it again before I go to Istanbul in two weeks.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William Ellisworth Artis (February 2, 1914 – April 3, 1977) was an African-American sculptor, whose favorite medium was clay. The freedom of modeling gave him a broad range of expression. During the latter part of his life, he began to focus on potting. He was a pupil of Augusta Savage and exhibited with the Harmon Foundation. He was featured in the 1930s film A Study of Negro Artists, along with Savage and other artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance, including Richmond Barthé, James Latimer Allen, Palmer Hayden, Aaron Douglas, Lois Mailou Jones, and Georgette Seabrooke. He taught at the Harlem YMCA after finishing high school, then was involved with Works Progress Administration's artist project. He served in the Army during WWII. He earned his academic degrees. He studied at the Art Students League of NY and Syracuse University. After leaving Syracuse, he taught at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in SD. He, with fellow artists Romare Bearden and Selma Burke, were together in the landmark Albany Institute of History and Art exhibit and over the next decade found the black artist making inroads in national exhibits and major galleries. He joined the faculty of Nebraska State Teachers College. He taught at Chadron State College, where he was a Professor of Ceramics, and at Mankato State College, as a Professor of Art. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CoKUW6GLsZ9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

With ‘Gems’ From Black Collections, the Harlem Renaissance Reappears

An ambitious new show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art uncovers work by long-ignored artists with the help of loans from Black colleges and family collections.

Laura Wheeler Waring’s “Girl in Pink Dress,” circa 1927, at the conservation studio of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan. The artist’s grandniece was determined to bring Waring the recognition she deserved.Credit...Gioncarlo Valentine for The New York Times.

By Aruna D’Souza

Feb. 18, 2024

How do you measure the United States in the 20th century without Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington?

You wouldn’t dream of it. The writers, poets, singers and musicians of the movement known as the Harlem Renaissance, centering around the New York neighborhood from 1919 to the end of the 1930s, loom large in the American cultural imagination. The period was when “Harlem became the symbol for the international black city,” as the novelist Ishmael Reed described it.

But what about the painters Laura Wheeler Waring, Charles Henry Alston and Malvin Gray Johnson? Or the sculptor Richmond Barthé? Hardly household names. And while other visual artists — Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, Archibald Motley Jr., Augusta Savage — have long been celebrated, their contributions have until recently been too often treated as a byway, separate from the rest of European and American modernism.

An ambitious new exhibition, “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” opening Feb. 25 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, hopes to shift our view of the time when Harlem, energized by the arrival of thousands of African Americans through the Great Migration, flourished as a creative capital.

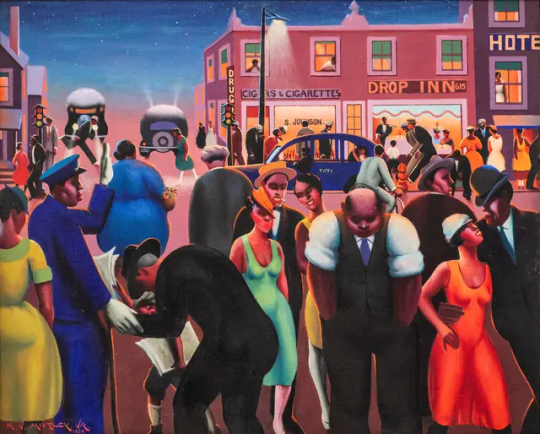

Archibald Motley Jr., “Black Belt” (1934), inspired by jazz culture, was loaned to the Met by the Hampton University Museum, in Virginia.Credit...Estate of Archibald John Motley Jr./Bridgeman Images, via Hampton University.

Maquette of Augusta Savage’s sculpture “Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp),” 1939. A massive version appeared at the 1939 World’s Fair celebrating African African contributions to music. Credit... University of North Florida, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Charles Henry Alston, “Girl in a Red Dress,” 1934. The painting, acquired in 2021 by the Met, is one of 21 objects from the museum’s collection in the show.Credit...Estate of Charles Henry Alston, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“When I was a student, none of the survey courses of 20th century art I took included the Harlem Renaissance,” said Denise Murrell, the show’s curator. “This was the first moment where you have Black artists portraying all aspects of a new, modern city life that’s taking shape in the ’20s through the ’40s. They were so international, spending extended periods of time in Europe and engaging with avant-garde aesthetics. They were in the middle of all of these crosscurrents, not as observers but as participants.”

And after years of being the subject of racial stereotyping, Black artists were able to tell their own stories, Murrell said. “They were trying to define, to be self-defining, to articulate their own sense of who they saw themselves being and becoming.”

Denise Murrell, the curator of the “Harlem Renaissance,” inside the conservation studio with a Waring painting behind her. She hopes the show will highlight the Harlem Renaissance’s central role in American and European modernism.Credit... Gioncarlo Valentine for The New York Times

Murrell, who completed a Ph.D. in art history at Columbia University after a 20-plus year career in finance, joined the Met in 2020. Now she’s taking up the challenge set by Alain Locke, a trailblazing critic during the Harlem Renaissance whose 1925 essay “The New Negro” became a touchstone for Black aesthetics. Locke encouraged artists to draw on African art — not the way European artists were doing, as a form of primitivism, but as an ancestral tradition. At the same time, he insisted that they should work in dialogue with, and show their work alongside, European modernists.

The Met exhibition will include around 160 paintings, sculptures, photographs, as well as books, posters, films and ephemera. Among these will be works by a handful of European modernist painters — Kees van Dongen, Henri Matisse and Edvard Munch among them — who were in dialogue with Harlem Renaissance artists, writers and musicians. The move is intended to underline Murrell’s thesis that this was indeed a trans-Atlantic movement.

‘Stupefying, clueless racism’

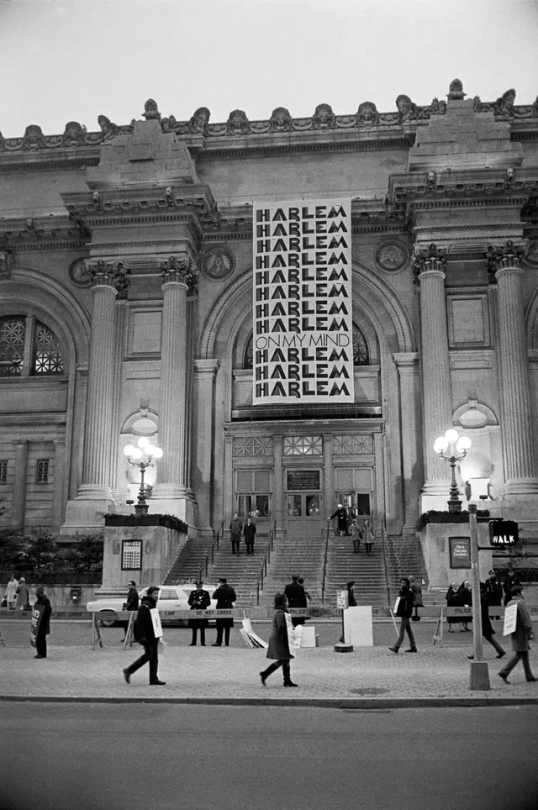

Installation view of “Harlem on My Mind: The Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968,” at the Met, 1969. At left: a mural of James Van Der Zee’s photograph of Adam Clayton Powell Sr., with the Sunday School of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, 1925. On the back wall: a 1925 photograph of a bank board.Credit...The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This is the second time the museum is doing an exhibition about Harlem; the first was in 1969. “Harlem on My Mind” was the brainchild of Thomas Hoving, a new director at the Met, who was anxious to bring diverse audiences into the institution, and an independent curator, Allon Schoener, who had a reputation for novel, multimedia displays that delved into the history of New York City.

Though the museum had collected and displayed African art, it had never broached the subject of African American culture. So it came as a surprise to Black artists, curators and community leaders to discover that “Harlem on My Mind” didn’t include a single painting or sculpture by an African American artist. Instead, Schoener relied on documentary photography, text, sound and other immersive strategies to convey the vitality of Harlem and its people.

The outcry was immediate: Several artists, including Benny Andrews, Camille Billops and Cliff Joseph, formed the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition. They picketed the museum every day, eventually drawing the attention of local news crews.

Demonstrators picketing outside “Harlem on My Mind” at the Met, 1969.Credit... Jack Manning/The New York Times

Murrell let out a sigh when asked about the show. “I was not hired by the Met to do a corrective show to get them over ‘Harlem on My Mind,’ ” she said firmly. “When you realize what the curators of that show were actually saying — ‘Well, there was no fine art in Harlem, so we don’t have to include any artists’ — you can see the stupefying, clueless racism of the endeavor, and that is a historical context that I think we inevitably do have to address.”

One of the bright spots of “Harlem on My Mind,” according to Murrell, was the presence of work by the photographer James Van Der Zee (1886-1983), who chronicled Harlem life during his long and prolific career. In 2021, the museum entered into a partnership with the Studio Museum in Harlem and Van Der Zee’s widow to establish an archive of his work, including 20,000 prints. Murrell’s exhibition will include some that have never before been shown. (The Met’s show comes more than 35 years after the Studio Museum’s own 1987 exhibition on the art of the Harlem Renaissance.)

A legacy built by Black institutions

William H. Johnson, “Woman in Blue,” circa 1943, oil on burlap. Works like this were collected mostly by historically Black colleges and universities like Clark Atlanta University Art Museum.Credit... via Clark Atlanta University Art Museum

Despite the lessons learned from “Harlem on My Mind,” the Met did not prioritize collecting work by African American artists until relatively recently. Only 21 objects in the upcoming show are from the Met’s collection, along with the suite of Van Der Zee’s photographs.

“We have such a spotty collection in terms of African American painting and sculpture, like all other P.W.I.s,” said Murrell, using the acronym for “predominantly white institutions.” To look at the movement in depth, the Met turned to loans from a handful of collectors and museums who have formed a rich repository of work by Black modernists of the early 20th century, including the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Manhattan and the Walter O. and Linda Evans collection in Savannah. (The National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., which also lent works to the Met, had received donations from the Harmon Foundation in the 1960s.)

Jacob Lawrence, “The Photographer,” 1942. Watercolor, gouache and graphite on paper. Lawrence’s painting captures the ethos of the Harlem Renaissance: Black artists and photographers depicting their own communities.Credit...2023 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Aaron Douglas, “Miss Zora Neale Hurston,” 1926, from Fisk University Galleries, Nashville, Tenn. Many artists in the show portrayed writers, musicians and performers of the era, though the artists themselves did not receive the same recognition. Credit...Heirs of Aaron Douglas/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Most important, it meant diving into the holdings of a group of historically Black colleges and universities, which were acquiring works from the start: Fisk University, Howard University, Clark Atlanta University, and Hampton University.

Because many museums at H.B.C.U.s have not had the financial resources or staffing to put their collections online, Murrell traveled to each campus in person to understand the full extent of their holdings. Kathryn Coney-Ali, the co-executive director at Howard University’s Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which lent six pictures, said she was heartened that well-resourced institutions — including the Met, the Getty Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Mellon and Ford Foundations “are seeing that there’s a need to preserve these collections, these assets, these cultural effects, at historically Black colleges and university because they’re gems.”

A family reunited, an artist rediscovered

Inside the Met's conservation studio, from left: Motley’s “Portrait of the Artist's Father,” circa 1922; and three paintings by Waring, “Mother and Daughter" (circa 1927), “Girl in Green Cap” (1930) and “Self Portrait” (1940).Credit...Gioncarlo Valentine for The New York Times

Some of those gems had been tucked away in attics and basements of artists’ families.

Roberta Graves had been on a yearslong mission to interest museums and curators in the work of her great-aunt, Laura Wheeler Waring, who had studied in Philadelphia and Paris and made a name in painting elegant portraits of the Black bourgeoisie and intellectuals starting in the 1920s.

The steward of about 30 of Waring’s paintings, hundreds of watercolors and her archive, Graves had been trying to garner attention for years — to no avail, she said in a phone interview.

In 2014, Graves recalled, a representative from the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia, visited the archive and suggested that, to avoid the headache of trying to find a home for the work, the family “might be better off burning” their Waring holdings. (The museum told The New York Times it had decided not to pursue further conversation about the works in question but that it would never have disparaged an artist’s legacy.) Not even the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Waring’s alma mater, seemed particularly enthused at the time.

Graves was so determined that she teamed up with another great-niece of Waring’s, Madeline Murphy Rabb. The two families — the Warings and the Wheelers — had been involved in a legal battle over the artist’s estate, and relations were strained. That was ancient history, as far as Graves was concerned. “I said, together we’re a much stronger force.”

Rabb had also found that recognition for Waring’s contributions was an uphill battle. “I’ve stalked curators, I’ve stalked presidents of museums,” she said in a phone conversation. “I consider it a responsibility.”

Just before the pandemic shutdown, they connected with Murrell, who had included a work by Waring in “Posing Modernity,” her much-praised exhibition at the Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in 2018.

When the three women finally met in Rabb’s Chicago living room to discuss plans for the Met’s show, there was celebratory dancing, Rabb recalled. The exhibition will now include nine works by Waring, including five paintings lent by Graves and Rabb.

Discoveries and appreciation

Isabelle Duvernois, a conservator at the Met, inspecting Waring’s “Yellow Roses” (undated).Credit...Gioncarlo Valentine for The New York Times

Duvernois cleaning a section of Waring’s “Mother and Daughter,” circa 1927.Credit... Gioncarlo Valentine for The New York Times

Murrell, right, the curator for the show, and Shawn Digney-Peer, a conservator, inspecting Waring’s self portrait, loaned by the artist’s grand-niece, Roberta Graves.Credit... Gioncarlo Valentine for The New York Times

Murrell and her colleagues realized that while some loans — like Aaron Douglas’s 1934 mural “From Slavery to Reconstruction,” part of his series “The Aspects of Negro Life,” normally installed high on a wall at the Schomburg Center — needed only a simple surface cleaning, others required extensive restoration. To stabilize these works, the Met relied on its team of veteran conservators, as well as those of museums around the country, and independent experts.

I met with Isabelle Duvernois and Shawn Digney-Peer in the Met’s conservation lab on the third floor mezzanine. They showed me a circa 1922 portrait that Archibald Motley Jr. made of his father, lent by the artist’s family. The picture is very dark, almost somber — utterly unlike the crowded scenes of jazz age sociability that Motley was best known for. The older man sits, elegantly dressed, in an armchair, with a book in his hand, a painting of a racing scene behind his head, and a small Asian porcelain figurine tucked along the canvas’s edge. It reflects the respect his father commanded in his community more than his actual power — Motley Sr. was a Pullman porter. Duvernois and Digney-Peer were surprised to learn that the tonality, which they first attributed to aging varnish, was entirely intentional on the painter’s part. “When it’s lit well, it doesn’t look dark; it hums,” said Digney-Peer.

“It’s made like an old master painting,” added Duvernois.

In the conservation lab, Waring’s 1930 “Girl in Green Cap,” on loan from Howard University, yielded the biggest surprise: “We saw an unusual passage in the background, so we did some infrared imaging and X-radiography,” Digney-Peer said. There was a second painting underneath — a portrait of two young girls, sitting side by side.

The Met's conservators were surprised to find a fully developed portrait of two girls hidden underneath Waring’s 1930 painting “Girl in Green Cap,” discovered in this radiograph.Credit... Gioncarlo Valentine for The New York Times

Murrell expects this type of conservation work will continue long after the exhibition. “We have the new wing,” she said, referring to the Met’s planned galleries for modern and contemporary art, the Tang Wing, due in 2029, at an estimated cost of $500 million.

“We want to have a very major Harlem Renaissance presence when that reopens,” she said. “We’re going to have acquisitions, and it’ll be an ongoing project.”

It’s hard not to share Murrell’s excitement for the upcoming show, and for its potential to reorient the view of an era scholars thought they knew. “It’s both a celebration of the period, a reintroduction of the period, a new introduction for people of a certain generation and from a certain art historical point of view,” the curator said.

If she’s right, students of succeeding generations will never take survey courses of art history that fail to include the Harlem Renaissance. And Murrell said she is optimistic, as well, that showcasing works from H.B.C.U. collections will “attract new support that goes directly to those museums, so they can build out their infrastructure and show more of what they have.

“There’s no reason a Fisk or a Hampton, with their impressive museums, couldn’t do a show of this scale,” she said, “if they only had the resources.”

Aruna D'Souza writes about modern and contemporary art and is the author of “Whitewalling: Art, Race & Politics in 3 Acts.” In 2021 she was awarded a Rabkin Prize for Art Journalism. More about Aruna D’Souza

0 notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (2/7/24)

Richmond Barthé (African-American, 1901-1989)

Blackberry Woman (1930)

Bronze sculpture, 90.1 x 31.1 x 41.3 cm.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

Barthé took the title "Blackberry Woman" from Wallace Thurman's 1929 book, "The Blacker the Berry: A Novel of Negro Life," a story of the discrimination against dark-skinned women within the African American community. The woman's bare feet, simple cotton dress, and thatched baskets evoke the extreme poverty of Barthé's youth in rural Mississippi where he often saw black women carrying bundles on their heads.

0 notes

Text

Richmond “Jimmie” Barthé (1901-1989), was an African-American sculptor and a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s.

0 notes