#SAI W20 Abstraction 06 Reconsideration

Photo

Last week, Irene made a painting that functioned as a graphic music score; it was a visual interpretation of one of her own compositions. I went in search of other examples of such scores, which I will share over the next few posts. At top we see examples from Tibet, possibly created in the 19th century. These are followed by a different form of notation: a drawing recording dancers’ movements in a ballet. More examples from this book of choreographic notation can be found at the source link below.

Tibetan MS 42, leaves from a yang-yig musical score, Wellcome Collection, London, U.K.

Tibetan yang-yig notation, date unknown. Dulduityn Danzanravjaa collection, Sainshand, Mongolia. Source.

Raoul-Auger Feuillet (1659 or 60-1710). Page 78: “Balet” from Choregraphie, 1700. Source.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The top two images show works by composers attached to Fluxus, an international, cross-disciplinary, experimental art movement. These visual scores appeared in this particular form in a 1963 publication created by movement organizer George Maciunas. Improvisational musician LaDonna Smith published her visual collage in 1980 and described it as “automatic drawing as a means of composing music.”

Yasunao Tone (Japanese b. 1935). Anagram for Strings 1961. Ink and typewriting on transparentized paper, 8 1/4 x 11 11/16 inches. Source.

Toshi Ichiyanagi (Japanese b. 1933). Music for Electric Metronome 1960. Ink and typewriting on transparentized paper, 11 3/16 x 15 3/16 inches. Source.

LaDonna Smith (American b. 1951). PARTBE 1980. Published in Heresies Magazine #10: “Women and Music,” New York, 1980. Image source here.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Claire B. Cotts (American b. 1964). Cotts’ forced drips add an element of intentional artifice to this imagery. They function as linear patterns allowing multiple colors to mix optically, and often act as a bridge between the different painted shapes.

Loblolly. Acrylic on canvas, 64 x 80 inches. Source.

The World, From Above & Below. Acrylic on panel, 72 x 48 inches. Source.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Brice Marden (American b. 1938). Marden’s aesthetic makes heavy use of correction and revision, the corrections themselves becoming structural components of the finished image.

Cold Mountain 2 1989-1991. Oil on linen, 108 1/8 x 144 1/4 inches. Source.

Hydra Diptych 1991. Ink, ink wash, and gouache on two joined pieces of Arches Satine paper joined with Japanese paper; 14 x 16 3/4 inches. Source.

Dragons 2000-04. Ink on paper, 40 1/2 x 29 3/4 inches. Source.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I spent some time this week thinking about the uses of drips in abstract painting. They can serve as a visual reminder of the fluid nature of paint while also acting as structural elements. The drips in Twombly’s acrylic painting have a very different visual effect than those in Bluhm’s oil. Johns frequently worked in wax, which drips more slowly and sets up more quickly. The drips in Flag allude to Abstract Expressionist painting techniques and also complicate the work’s odd relationship to image--it’s a painting of a flag that has the proportions and appearance of an actual flag, accurate but full of visual reminders of the artist’s hand.

Cy Twombly (American 1928-2011). Sans titre (Gaète) 2007. Acrylic, wax crayon on wood panel, 99 1/4 x 217 1/4 inches. Museum Brandhorst, Munich. Source.

Norman Bluhm (American 1921-1999). Unknown Nature 1956. Oil on canvas, 51 x 76 1/2 inches. Source.

Jasper Johns (American b. 1930). Flag 1954-55. Encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted on plywood, three panels; 42 1/4 x 60 5/8 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Flag 1954-55 (detail). Photo by Steven Zucker. Source.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

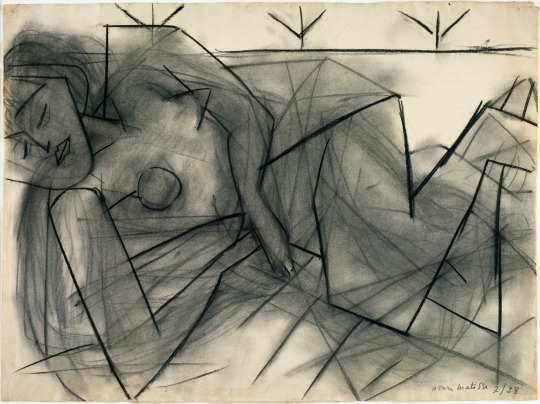

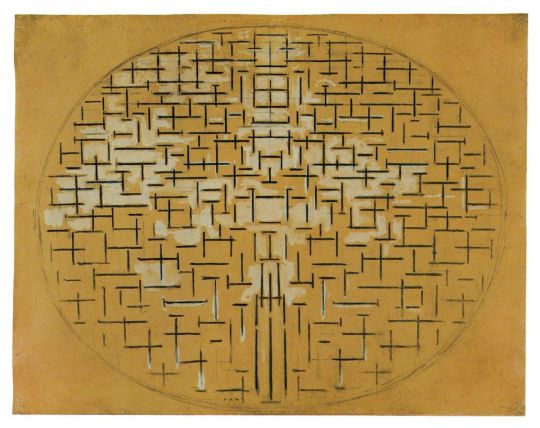

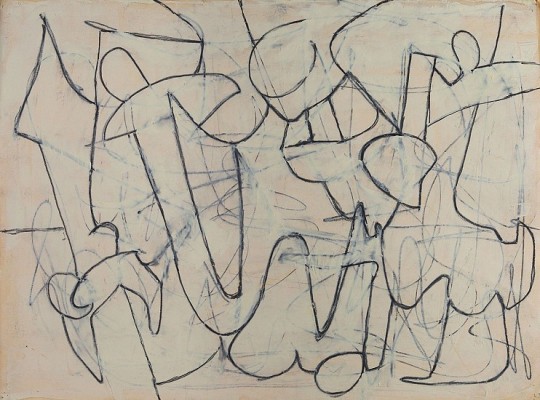

Four Modernist painters whose reconsidered marks remain visible. Matisse’s web of erased charcoal lines shows us that this single drawing had many iterations, while Mondrian’s changes are more modest (and, presumably, have become more noticeable as the paper has yellowed over time). Charlotte Park gives us two examples showing how reconsideration was an important part of developing her improvisational imagery.

Henri Matisse (French 1869-1954). Reclining Nude July 1938. Charcoal on paper, 23 5/8 x 31 7/8 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Piet Mondrian (Dutch 1872-1944). Pier and Ocean 5 (Sea and Starry Sky) 1915 (inscribed 1914). Charcoal and watercolor on paper, 34 5/8 x 44 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Source.

Charlotte Park (1918-2010). Untitled (50-67) c. 1950. Gouache and oil on paper, 18 x 24 inches. Source.

Untitled (60-14) c. 1960. Gouache on paper, 11 3/4 x 14 1/4 inches. Source.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Richard Diebenkorn (American 1922-1993). Like Marden, Diebenkorn chose to make his corrections in paint colors that often contrasted with the color of the ground. The lines in the 1970 drawing are almost entirely covered over, but the gray paint calls attention to what he’s done.

Untitled (Ocean Park Series) 1974. Opaque watercolor, acrylic, and graphite; 28 7/8 x 21 1/8 inches. The Morgan Library and Museum, New York.

Untitled 1970. Charcoal, gouache, and watercolor on paper; 23 3/8 x 19 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Untitled (Ocean Park) 1977. Acrylic, gouache, watercolor, cut-and-pasted paper, and pencil on cut-and-pasted paper; 18 5/8 x 33 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Amy Sillman (American b. 1955). Here’s how Sillman describes her process of painting and revision:

I have a really complicated procedure. I will attempt to overcome, paint out, destroy, erase, undo as I do things. My work is painted and destroyed 100 times before anyone besides me ever sees it. The result is a complicated surface that has been touched in many ways, with a strong sense of attachment and antagonism. (Source.)

Nose 2010. Oil on canvas, 90 x 84 inches. Source.

B 2007. Oil on canvas, 45 x 39 inches. Source.

Duel 2011. Oil on canvas, 90 1/2 x 84 1/2 inches. Source.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Iannis Xenakis (Greek, lived in France, 1922-2001). Two of Xenakis’ remarkable visual scores. Mycenae Alpha was meant to be realized on an electronic device designed to convert visual images into sound. Compare Study for Terretektorh with the Cy Twombly drawing that follows it.

Mycenae Alpha (for mono tape, composed on the UPIC system) 1978.

Study for Terretektorh c. 1965-66. Color pencil on paper, 8 1/2 x 11 3/4 inches. Iannis Zenakis Archives, Bibliothèque national de France. Source.

Cy Twombly (American 1928-2011). Untitled 1969. Oil-based house paint, wax crayon, and graphite on canvas; 78 1/2 x 94 1/2 inches. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

0 notes

Photo

John Cage (American 1912-1992). Cage was a composer who incorporated chance happenings into performances of his music, but these accidents were always contained by some sort of structuring device. The score for Fontana Mix contained sheets of printed linear artwork as well as transparent overlays and instructions on how to use these documents to generate a unique performance. Cage was friendly with many visual artists, and used chance operations to create paintings of his own. The watercolor seen here was made with a feather dipped in paint, tracing around river stones collected by the composer.

Score for Fontana Mix 1958. Source.

New River Watercolor, Series 1, #3 1988. Watercolor on paper, size unknown. Source.

0 notes