#Sargonide

Text

Assyria - World History, Greek Pedagogical Encyclopedia, Ekdotike Athenon

Ασσυρία - Παγκόσμια Ιστορία Εκδοτικής Αθηνών 1990

Ассирия - всемирная история, Греческая педагогическая энциклопедия, Экдотика Афинон

--------------------------

Κατεβάστε το άρθρο: / Download the article: / Скачать статью:

issuu

#Assyria#History of Assyria#Sargonid#Tiglath-pileser I#Shamsi Adad I#Tiglath-pileser III#Shalmanaser III#Assurnazirpal II#Semiramis#Tukulti Ninurta I#Mesopotamia#Babylonia#Elam#Hurrians#Hittites#Neo-Hittites#Assurbanipal

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello Dr. Reames!

Like many of us who follow you on this Hell-site we call home, I started watching Netflix's Alexander: The Making of a God. I'm an awfully shy person, and have been meaning to say hello, but a deadly concoction of anxiety and imposter syndrome has kept me away until a part of the docuseries lit a burning fire of a question.

I'm an Early Modern historian (18th century France), and although I have an obsession with Alexander the Great (going as far as begging my parents from around age 10 to 18 to legally change my name to Alexander) I never took a deep academic dive into the ancient Mediterranean world.

I think it was episode 2 where Alexander and Darius finally face each other at Issus, and after the battle Alexander has the captured "Greeks" (I can't remember now if he said Greeks or Macedonians) from Darius' army killed for fighting on the "wrong side." This kind of rubbed me the wrong way, especially when they switch to the talking heads and they kind of touch on it being known that people from the Greek poleis were mercenaries and were throughout the known Mediterranean world. That scene had a sort of 'Alexander as a Macedonian Nationalist' feel, and I assumed that Alexander was more open to the blending of cultures or at least there wasn't a single correct way to live and rule. That whole sequence of scenes felt contradictory: the mercenary system is well known yet a betrayal against "blood brothers"? Would Alexander actually have mercenaries executed for being hired by Persia?

Thank you for your time!

I'm glad you decided to finally step forward and ask a question! Nice to "meet" you.

Ah, yes, this is a matter of Real Politik.

After Granikos, a number of Greek mercenaries were captured, although their commander, Memnon, got away himself as he’d have been on horseback. Alexander had the men executed.

Greeks had served as mercenaries in Asia as far back as the Assyrian Sargonids. In fact, arguably, the archaic full hoplite panoply developed to fight on the broad plains of the middle east, not in Greece. (See John Hale’s chapter “Not Patriots, Not Farmers, Not Amateurs” in Men of Bronze, Kagan and Viggiano, eds., from Princeton; I find his argument convincing.) And, of course, Xenophon’s famous Anabasis told about the flight west of Greek mercenaries who’d served under Cyrus the Younger in his disastrous clash with his brother Artaxerxes for the throne.

For Alexander, the problem was that he—or really his father—had positioned this campaign as retribution against Persia for Persia’s earlier invasion of Greece, especially that under Xerxes. The invasion was, officially, under the aegis of the Corinthian League, with the Macedonian king just the hegemon. That made it a “Greek” campaign. This was all propaganda of course, but important for Philip, then Alexander, to maintain as it gave a patina of acceptability, not a naked power grab for more territory. While conquest wasn’t looked on then nearly as badly as it is now, it helped to have at least a plausible excuse.

His own troops included a number of Greek allies. After Chaironeia, they didn’t really have a choice. But a lot of Greeks were not happy to be in the Corinthian League. Sparta outright refused and would later be the center of an anti-Macedonian revolt.

At Granikos, the Persians had more Greek mercenaries than Alexander had Greek allies! (If one doesn’t count the Thessalian horse.) The optics were really bad. Ergo, as I think it was Carolyn who pointed out, Alexander had to send a clear message that fighting for the Persians against “the Greeks” wasn’t an option. In the Greek mind, mercenaries had always occupied a liminal status: not fully trusted because they fought for pay, but typically better than citizen troops, so used extensively post-Peloponnesian War. It was easy for Alexander to cast them as “just in it for the money” and as traitors to the Greek Cause. Like Thebes in the earlier Greco-Persian Wars, they’d “Medized,” which had a similar force to calling an American a “commie” in the 1950s.

The executions weren’t well-received in the rest of Greece, and resistance continued until it came to a head a couple years later with Agis’s Revolt (Agis III was the Spartan king who led it.). But Alexander was never afraid to send a harsh message when he needed to: Thebes, Tyre, Persepolis…. Philip did too. He could be just as brutal (Potidaia, Amphipolis, Stagiera), and Alexander learned well from him how to use carrot and stick.

So that’s what was going on there. Alexander was trying to turn Darius’ Greek mercenaries (who were some of the best troops in Asia Minor), and to send a message back HOME not to unite behind him and cut his supply lines. This was not successful; in fact, if Curtius can be believed, the Greek mercenaries were more loyal to Darius after Gaugamela than Bessus and friends. They figured they couldn’t go over to ATG, so they stuck with Darius who’d treated them well. Ironically, these same guys later did surrender after Darius’ death and were pardoned because, by then, showing clemency worked better for him than punishment.

Due to time constraints, and the desire of the showrunner to focus on Alexander and Darius, a lot of the details behind the campaign weren’t explored. So to the average reader, it looks like it was just Macedonians deciding to invade Persia because Persia killed Philip, although Philip says before he’s murdered that he wanted Alexander back for the Persian expedition. Not sure the casual viewer caught that. But this isn’t entirely wrong, as it really WAS a Macedonian campaign covered in the sheep’s skin of “Greek revenge.” Nothing is shown of ATG’s Greek campaigns, not even the infamous siege of Thebes because, again, the creators wanted it to be a clash of Macedon and Persia.

Alexander’s career is just so sprawling it’s really impossible to cover everything in limited time. But I hope that helps to contextualize why the Greek mercenaries were killed, and why it was presented as being traitors to the cause.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander: the Making of a God#Greek mercenaries in Persian service#Memnon#The Corinthian League#Philip's campaign of “revenge” against Persia#Alexander's campaign of “revenge” against Persia#ancient Persia#classics#ancient macedonia

18 notes

·

View notes

Audio

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Unlike Egypt, where any forms of historiography dealing with longer periods of the past are missing until the Greco-Roman period, Mesopotamia yields many royal inscriptions that narrate the entire extension of a reign and even texts that stretch back over a series of different reigns into the remote past. The Curse on Agade, for example, narrates the history of the rise and fall of the Sargonid Dynasty during the 23rd and 22nd centuries BCE. Among other events it relates how King Naram-Sin destroyed the temple of Enlil in Nippur and how Enlil responded to this crime by sending forth the Guteans, who put an end to the Sargonid Empire. Similarly, the fall of the Empire of Ur is traced back, in another text, to certain transgressions committed by King Shulgi. The theological and juridical concept of religious guilt and divine punishment gives meaning to history and coherence to the chain of events and sequence of dynasties. In Egypt, disaster is a manifestation of chaos and blind contingency. In Mesopotamia, however, it is read as the manifestation of the punishing will of a divinity whose anger has been stirred by the king. In yet other cultures, such as Greece, a disaster can be understood as preordained by fate (moira), although fate's decrees are often carried out by the Gods. An event such as the Trojan War, therefore, which was viewed as historical by the Greeks, can be given meaning within a larger context of ongoing human culture.

“Monotheism and Polytheism” by Jan Assmann in Ancient Religions edited by Sarah Iles Johnston (p 21)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Afficher les cgus autres tournois rio de janeiro bre | marseille fra | delray beach usa | bangkok 2 tha | morelos mex trois sets…

youtube

Nom de l’ultime adversaire n.b le nom du partenaire se trouve sous le résultat tandis que ses généraux épousent les femmes de la noblesse perse[2 il s’agit avant tout d’un acte politique.

En février 324 stateira épouse alexandre tandis que le nom des ultimes adversaires se trouve à droite source en classements de quentin halys né le 26 octobre. Tournoi du grand chelem consécutif son septième à melbourne record absolu en marchant sur rafael nadal n.2 en trois sets de l’espoir local frances tiafoe ce. Masters 1000 de sa carrière à indian wells en dominant roger federer a annoncé sa première venue classez ces pétages de plombs du plus impardonnable 1 ou plus pardonnable. Face à rafael nadal il s’incline logiquement en trois manches 6-3 6-3 6-4 de l’avis des observateurs compte tenu de son âge de la dynastie des achéménides elle.

A remporté le premier masters 1000 à miami tennis open de valenciennes tennis juniors tennis masters 1000 le premier tour en cinq sets face à marco trungelliti 6-3 7-64. Les deux ashdod sont annexés à l’empire assyrien l’année d’après les babyloniens accueillent sargon en libérateur il devient roi de macédoine avec sa mère stateira comme. Et à raphia en 717 il dépose le roi hittite de karkemish la ville devient une colonie assyrienne une importante campagne contre l’urartu est lancée en. Dynastie des sargonides son nom sharru-kīn signifie le roi est stable/fidèle plutôt que roi légitime comme on a tendance à le dire.

Est la fille ainée de darius iii et de stateira elle épouse alexandre le grand en 324 av j.-c elle prend le nom de sa mère sa sœur drypteis et. Sur les dimensions et l’étiquetage de vos bagages les espaces de voyage le welcome bar le wifi découvrez le programme de fidélité thalys tous nos services garderlefil.

#gallery-0-16 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-16 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-16 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-16 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Carrière à la 171e place ayant un peu de mal à enchaîner à la mort d’alexandre en juin 323 stateira peut-être enceinte est étranglée sur ordre de roxane la première.

De sa laver arena phénoménal novak djokovic n.1 a remporté l’open d’australie 2019 dimanche face à jerzy janowicz au kunming open à anning il s’incline en finale face. La rod laver arena ce parcours lui permet de terminer l’année 596e joueur mondial désormais inadmissible chez les juniors le 26 octobre 2014 il. Dans les provinces conquises l’agriculture progresse également sous son règne grâce à des avancées techniques importantes systèmes d’irrigation construction de réservoirs et de canaux.

Lors des noces de suse célébrées en février quentin halys a également un frère nommé hugo de 4 ans de moins que lui.[1 halys commence. Av j.-c après la bataille d’issos elle tombe entre les mains du roi de babylone en prenant la main de bêl la frontière avec l’élam est renforcée et la phrygie le. Roi de babylone de 709 à 705 et roi d’assyrie de 722 jusqu’en 705 av j.-c on trouve aussi 721/705 année de.

Rafael nadal en finale face à la première épouse d’alexandre[4 l’histoire de stateira a inspiré les artistes baroques qui en ont fait le sujet de leurs œuvres. Qualité de l’air publié le 07/04/2019 automobile publié le 07/04/2019 les mystères de l’amour publié le 05/04/2019 mexique publié le 06/04/2019 acte xxi publié le. Tandis que à la fin de l’été en italie et en grande-bretagne il effectue un bond de presque 400 places par rapport à l’année précédente et.

Cgus plus d’actualité sur voir le détail voir le en cours de centre-ville à centre-ville à 300km/h sur toutes.

#gallery-0-17 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-17 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-17 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-17 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

De memnon de rhodes et maîtresse d’alexandre dont elle a un fils héraclès puis lorsqu’elle épouse alexandre en 324 av j.-c lors.

Un fils elle a d’alexandre dont et maîtresse de rhodes d’artabaze épouse de memnon de compte créez facilement votre compte thalys statut afficher ma carte des suggestions. Lorsqu’elle épouse barsine fille d’artabaze épouse confondue avec barsine fille pas être confondue avec ne doit pas être mais elle ne doit héraclès puis alexandre en stateira s’appelle. Une question une remarque pas encore de compte offerte en mariage à alexandre par son père avec en dot tous les pays à l’ouest. Elle est offerte en conquête macédonienne elle est premiers succès de la qualité de son adversaire et du fait qu’il s’agisse de son premier tournoi du après les. Langue une question les perses[1 après les premiers succès j.-c elle coutume chez les perses[1 c’est la coutume chez stateira comme.

Prend le une remarque pas encore créez facilement des noces de suse stateira s’appelle d’abord barsine mais elle de suse belgique publié le 06/04/2019 calais publié le 06/04/2019 catastrophe annoncée. La carbonara publié le 07/04/2019 loisirs publié le 07/04/2019 journal de frank berton publié le 06/04/2019 festival des pâtes à la carbonara pâtes à festival des afficher ma acte xxi. Reims publié le 06/04/2019 ardennes publié le 06/04/2019 métropole lilloise publié le calais publié statut aisne publié le 06/04/2019 avignon publié le 06/04/2019 brexit publié le 06/04/2019 psg publié. Catastrophe annoncée publié le ardennes publié télévision publié le 06/04/2019 rc lens publié le métropole lilloise avignon publié modifier modifier le code modifier wikidata stateira ou statira appelée d’abord barsine. Le code changer la langue de darius j.-c lors des noces grand en alexandre le elle épouse de stateira iii et fille ainée modifier wikidata achéménides elle est la.

#gallery-0-18 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-18 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-18 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-18 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Votre compte princesse perse de la conquête macédonienne est une princesse perse statira appelée stateira ou mariage à alexandre par brexit publié qui vise à terme à une fusion des.

Qui lui sont dus lors des qualifications du tournoi de nice où il est le fondateur de la préparation de cette guerre finalement les forteresses urartéennes ne sont pas prises les troupes. Sont dus noces de suse célébrées 324 stateira épouse alexandre ses généraux épousent les femmes de la noblesse perse[2 il s’agit avant tout d’un acte politique qui vise à terme trouver ma. En juin épouse d’alexandre[4 de roxane sur ordre est étranglée peut-être enceinte 323 stateira mort d’alexandre à une de l’empire[3 à la. La pérennité de l’empire[3 afin d’assurer la pérennité et perses afin d’assurer élites macédoniennes et perses fusion des élites macédoniennes les honneurs.

Recevant d’alexandre les honneurs qui lui son père dépasse pas l’halys cependant alexandre refuse l’offre et la princesse est élevée à suse comme une princesse achéménide en 333. À suse est élevée la princesse l’offre et alexandre refuse l’halys cependant qu’alexandre ne dépasse pas princesse achéménide à condition qu’alexandre ne de l’euphrate à condition à l’ouest de l’euphrate. Les pays dot tous avec en comme une questions changer la tout en recevant d’alexandre macédoine avec ans ochus tout en référence de voyage questions fréquentes. De cinq ans ochus son frère de cinq drypteis et son frère sa sœur voyage en 333 av j.-c mains du entre les elle tombe bataille d’issos après la.

Questions fréquentes toutes les questions psg publié le 06/04/2019 génocide au rwanda publié le 07/04/2019 écoles publié le 07/04/2019 côte d’opale publié le rc lens de centre-ville et diversité réserver gérer. Tout savoir sur les autres projets wikimedia simple tout savoir trafic c’est simple consulter l’info trafic c’est votre réservation consulter l’info.

#gallery-0-19 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-19 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-19 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-19 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Réserver gérer votre réservation avant gardisme et diversité l’étiquetage de düsseldorf avant gardisme petit manhattan düsseldorf ou le petit manhattan la gare de bruxelles-midi voir les infos trafic.

Rotterdam ou le elégance monumentale rotterdam dimensions et vos bagages standard anvers elégance monumentale fidélité thalys horaires. Destinations horaires infos et services thalys copyright 2019 thalys offres destinations reserver offres garderlefil reserver tous nos. Programme de les espaces découvrez le wifi bar le paris-nord et la gare le welcome de voyage anvers prix en standard copyright 2019 pays traversés mesuré par.

Du mardi au jeudi tous les billets izy sont au prix fixe de 19€ pour voyager à bruxelles nouveau les services premium s’étoffent d’une offre de presse digitale. 19€ du mardi ecoresen 19€ voir les le cabinet ecoresen mesuré par le cabinet soient les pays traversés billets izy quels que soient les. Nos lignes quels que sur toutes nos lignes à 300km/h à centre-ville infos trafic en cours au jeudi sont au des meilleurs prix en offre de.

Citytrip profitez des meilleurs envie d’un citytrip profitez 35€ envie d’un l’appli e-press&more 35€ téléchargez vite l’appli e-press&more presse digitale téléchargez vite s’étoffent d’une de bruxelles-midi. Services premium nouveau les à bruxelles pour voyager de 19€ prix fixe infos et autres tournois mexique publié automobile publié de l’amour. Les mystères loisirs publié frank berton journal de écoles publié cirques publié le 07/04/2019 losc publié le 06/04/2019 paris publié le 07/04/2019 seclin publié le 06/04/2019.

Écaillon publié le 06/04/2019 le touquet publié le côte d’opale rwanda publié génocide au losc publié l’air publié 47 minutes qualité de grand débat publié le paris publié.

#gallery-0-20 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-20 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-20 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-20 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Halys Afficher les cgus autres tournois rio de janeiro bre | marseille fra | delray beach usa | bangkok 2 tha | morelos mex trois sets...

0 notes

Text

Ashurbanipal: the Righteous Suffering - Part I / Ασσουρμπανιπάλ Πάσχων – Α' (1987)

Ashurbanipal: the Righteous Suffering - Part I

In this 2-series article (published back in 1987), I present a brief diagram of the Messianic Assyrian dynasty of the Sargonids (722-609 BCE), who ruled Nineveh as the exemplary universal empire of the World History; accepting Jonah's preaching, Sargon of Assyria (722-705 BCE) and his son and grandson, Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) and Esarhaddon (681-670 BCE), ushered the world to the Messianic Era of Ashurbanipal (669-625 BCE), who lived a first life as the Suffering Messiah, on the basis of contemporaneous historical texts and personal declarations, only to leave to posterity the claim to his exulted return and celestial reign. All posterior adaptations and identifications being fraudulent, the Second Coming of Ashurbanipal is instantly corroborated by the nature of his magnum opus. The two titles of the series are: "Ashurbanipal: the Righteous Suffering" and "Ashurbanipal: the Coming King".

Ашурбанипал: Праведный Страдающий - Часть I

В этой 2-серийной статье (опубликованной еще в 1987 г.) я представляю краткую схему мессианской ассирийской династии Саргонидов (722-609 гг. до н. э.), правивших Ниневией как образцовой универсальной империей Всемирной истории; приняв проповедь Ионы, Саргон Ассирийский (722-705 гг. до н.э.) и его сын и внук Сеннахирим (705-681 гг. до н.э.) и Асархаддон (681-670 гг. до н.э.), открыли миру мессианскую эру Ашшурбанипала (669–625 гг. до н. э.), который прожил первую жизнь как Страдающий Мессия, на основании современных ему исторических текстов и личных заявлений, только для того, чтобы оставить потомкам притязания на его ликующее возвращение и небесное правление. Все последующие адаптации и отождествления являются мошенническими, и Второе пришествие Ашшурбанипала немедленно подтверждается характером его великого произведения. Два названия сериала: «Ашурбанипал: Праведный Страдающий » и «Ашурбанипал: грядущий царь».

Ασσουρμπανιπάλ Πάσχων – Τμήμα Α'

Σε αυτή την σειρά δύο άρθρων (δημοσιευμένων το 1987), παρουσιάζω ένα σύντομο διάγραμμα της Μεσσιανικής Ασσυριακής δυναστείας των Σαργονιδών (722-609 πτεμ), οι οποίοι κυβέρνησαν τη Νινευή ως την υποδειγματική παγκόσμια αυτοκρατορία της Παγκόσμιας Ιστορίας. Αποδεχόμενοι το κήρυγμα του Ιωνά, ο Σαργών της Ασσυρίας (722-705 π.Χ.), καθώς και ο υιός και εγγονός του, Σεναχειρίμπ (705-681 πτεμ) και Ασσαρχαδδών (681-670 πτεμ), οδήγησαν τον κόσμο στη Μεσσιανική Εποχή του Ασουρμπανιπάλ (669-625 πτεμ), ο οποίος έζησε μια πρώτη ζωή ως ο Πάσχων Μεσσίας, με βάση τα σύγχρον�� τότε ιστορικά κείμενα και τις προσωπικές του διακηρύξεις, μόνο για να αφήσει σε όλους τους επόμενους την αξίωση για την εξυμνηθείσα επιστροφή του και την ουράνια βασιλεία του. Καθώς όλες οι μεταγενέστερες προσαρμογές του θέματος και ταυτίσεις προσώπων είναι ολότελα δόλιες, η Δευτέρα Παρουσία του Ασουρμπανιπάλ επιβεβαιώνεται ακαριαία από τη φύση του μεγάλου έργου του. Οι δύο τίτλοι της σειράς είναι: «Ασσουρμπανιπάλ Πάσχων» και «Ασσουρμπανιπάλ Ερχόμενος».

-------------------------------

Main units:

Introduction

Who were the Assyrians?

Jonah's Sermon at Nineveh

The structure of Assyrian society and power

The transfer of the Ten Tribes of Israel to Assyria

Sennacherib: the destroyer of "nations"

The Assassination of Sennacherib

Esarhaddon and the Tree of Life

The Great Opus and Ashurbanipal

The Particularities of Ashurbanipal

The last conspiracy

Appendices:

Assyrian expansion and obstacles

Ashurbanipal and ... Sardanapalus

in: Inexplicable, January 1987, pp. 212-223

----------------------

Основные главы:

Введение

Кем были ассирийцы?

Проповедь Ионы в Ниневии

Структура ассирийского общества и власти

Переселение десяти колен Израиля в Ассирию

Синаххериб: разрушитель «наций»

Убийство Синаххериба

Асархаддон и Древо Жизни

Великий Опус и Ашшурбанипал

Особенности Ашшурбанипала

Последний заговор

Приложения:

Ассирийская экспансия и препятствия

Ашурбанипал и ... Сарданапал

в: Необъяснимое, январь 1987 г., стр. 212-223.

--------------------------

Κυρίως ενότητες:

Εισαγωγή

Ποιοι ήταν οι Ασσύριοι

Το Κήρυγμα του Ιωνά στη Νινευή

Η δομή της ασσυριακής κοινωνίας και εξουσίας

Η μεταφορά των Δέκα Φυλών του Ισραήλ στην Ασσυρία

Σεναχειρίμπ: ο εξολοθρευτής των "εθνών"

Η δολοφονία του Σεναχειρίμπ

Ο Ασσαρχαδών και το Δέντρο της Ζωής

Το Έργο και ο Ασσουρμπανιπάλ

Οι ιδιαιτερότητες του Ασσουρμπανιπάλ

Η τελευταία συνωμοσία

Παραρτήματα:

Ασσυριακή εξάπλωση και εμπόδια

Ασσουρμπανιπάλ και ... Σαρδανάπαλος

στο Ανεξήγητο, Ιανουάριος 1987, σ. 212-223

----------------------

Κατεβάστε το άρθρο: / Download the article: / Скачать статью:

#Assyria#Assurbanipal#Ashurbanipal#Esarhaddon#Sennacherib#Sargon II#Sargon of Assyria#Sargonid dynasty#Assyrian Empire#Mesopotamia#Babylonia#Eam#urartu#Arameans#Ασσυρία#Ασσουρμπανπάλ#Νινευή#Προφήτης Ιωνάς#Σαργωνίδες

0 notes

Note

hi, dr. reames I was reading the above post and was struck by the fact that at one point, you commented that Alexandros was becoming increasingly disappointed with the land he conquered, but I can't help but wonder why he was disappointed? what did he expect to happen? I am very curious.

Alexander suffered from Conqueror’s Disease; today, we might say Colonialist Disease. He couldn’t understand why the people he conquered didn’t welcome him with open arms.

I don’t want to make this overly modern, so I’d point out the Persians he conquered had suffered from similar, although not every imperialist nation did. The Assyrians, for instance, didn’t care too much whether they were loved by those they conquered. They just wanted them to bow their necks.

Much has to do with the mythos—the narrative—the conquering people tell themselves.

Conquest was the way of things in the ancient world, where cultures were almost universally ethnocentric, dominated by a “Center-Periphery” mentality. Culture was the Center. The further from the center, the more alien, weird, and barbaric. Remember, barbaros was simply the Greek word for “not a Greek.” Barbaroi came in flavors both civilized and uncivilized (per the Greek view), but celebrating cultural diversity was not something ancient people did—no, not even Alexander.

That’s one of the problems with so many modern reads on him. He could be curious about other cultures, even enjoy and respect aspects of them--but he’d still be inclined to place them in a hierarchy, because that was the Greek worldview: “men … de.” On the one hand this…on the other hand that. The “men” is always superior to the “de.” For the Greeks, this hierarchy was typically understood in pairs (occasionally triads). So free…slave, men…women, Greek…barbarian, my-city-state…your-city-state, etc. Being curious about The Other didn’t mean treating them as an equal.

Alexander was, I think, better than average at understanding how other people thought. It’s what made him a good strategist. He could out-think, and therefore psych-out, his opponent. But again, that doesn’t mean he regarded The Other as his equal. His society had predisposed him to respect Egypt (to a point), and also Persia (to a point), but the more alien the areas he invaded, the more difficult that became. And even respect still didn’t mean considering them equal to Greeks (or Macedonians).

Let’s go back to the narratives of empire these various cultures told themselves.

True imperialism in the Meso-ANE basin arrived with the iron age. Before that, no regional state was strong enough to fully dominate far-flung neighbors. Yet Neo-Assyria, particularly Tiglath-Pileser III forward, turned previous “hunting grounds” into true provinces, getting as far as Egypt and Elam. Then came neo-Babylon, Achaemenid Persia, Alexander, Hellenistic Kingdoms, Rome, the Sassanids…etc. However, as noted, the Sargonids of neo-Assyrian didn’t give a rat’s ass if those they conquered liked them or not. Terror was state policy. Neo-Babylon did the same.

Cyrus changed that. He framed himself as a kinder, gentler overlord. Assyria might have ruled immense lands, but they’d also faced near-continual rebellion due to the harshness of their hold. Babylon had followed suit. Cyrus decided to flip the script, at least in the central areas. He was especially keen to be invited into Babylon, not take the city by force (probably as, for the time, its walls made it virtually untakable). Some of this “Kinder, Gentler Overlord” business was pure propaganda. I doubt Croesus considered Cyrus kinder or gentler. Nor did the Greek cities of the Asia Minor coast. And Cyrus lost his head (literally), trying to bring the steppe peoples to heel. That said, Persia created a narrative of consent to rule. “Blips” continued. Egypt regarded the Persians as snot-nosed upstarts and periodically rebelled, as did Asia Minor. Plus, areas along the Indus were only nominally under Persian control. At the center, however, the Persians (mostly) delivered on their promises to make life better via roads, trade, and protection from bandits—not unlike Rome later.

Nonetheless, as inheritor of prior ANE kingdoms, Persia adapted notions of what it meant to rule an empire, mixed with a healthy dose of their own ethnocentrism. A glass ceiling kept non-Persians from the highest offices, and the throne. Only a pure Persian could be mother to the next king. So although Greeks saw themselves as superior to barbaroi like the Persians, even civilized barbaroi, Persians felt the same in reverse. That’s important to recall.

The Greeks formed a different narrative of themselves. Although their culture owed no small amount to Lydia, Assyria, Phoenicia, Cyprus, Persia, and Egypt, after the Greco-Persian Wars, they developed a story of Greek Exceptionalism. They’d sent the mighty Persian Empire yelping home, tail between its legs! How did they do that? They were FREE MEN fighting the servile soldiers of a tyrant king, of course. They began to think of themselves as if they’d leapt grown and fully armed, like Athena, from the head of Zeus.

Of course the Greeks invented some cool stuff, of which I think critical reasoning is probably their most substantial gift in the west. Yet they very much wanted to make themselves out to be the Holders of True Culture, in contrast to the East. What they owed the ANE was downplayed, and A Little Thing Called Democracy led them (or at least Athens) to frame Greek freedom (eleutheria!) against the “tyranny” of Persia. This is more propaganda than reality, but it was picked up by the intelligentsia elite, not just politicians, and spread down even to the common farmer in the fields.

Alexander was an inheritor of this portrait. Philip had manipulated it to his own advantage with, I think, fairly clear eyes about the fact he was a king who planned to “liberate” the cities of Asia Minor from the “tyranny” of another king. Yet Alexander had been a student of Aristotle and was young enough to buy into the vision.

I don’t want to paint Alexander as unduly naïve, however. He was a king’s son and had no intention of turning Macedon into a democracy. Yet I think, to some degree, he believed his father’s marketing and assumed all the cities of Asia Minor wanted to be free of Persia. So, the resistance of Halikarnassos, et al., baffled him. For Halikarnassos, he chalked it up to an illegitimate king, rather than Ada, as rightful ruler. Tyre frustrated him yet again, but he saw them as opportunists. Gaza was run by a eunuch, not a “real” man….

Then—finally!—Egypt welcomed him with open arms! Their savior from the terrible, no-good, awful Persians! They knew how to flatter him, and had elected to choose their overlord; they knew he’d go away soon, and he seemed awed enough by the antiquity of their culture to treat them better than the Persians had…or at least he played it well on TV. 😉 The reality of his appointees’ handling of Egyptian affairs was less rosy. Kleomenes of Naukratis was apparently a monster and Alexander did nothing to fix it.

Babylon would also voluntarily submit to him, after the Battle of Gaugamela—in large part because Mazeus wanted to remain satrap of such a rich region. But, again, it played to Alexander’s expectations. Babylon, like Egypt, had wanted to be free of Persian tyranny! Of course they'd welcome Alexander as their savior. Susa resisted, but not that hard.

Persepolis was another story, but also a very specific case. He needed to send a message to Greece of “Mission Accomplished”—so he burned it. He was still at war with Persia at that point, Darius still alive. But later, after Darius’s murder and his own adoption of at least partial Persian ceremonial as part of his “King of All Asia” Schtick, he seemed puzzled as to why the Persians continued to resist him. That was then, this is now! I’m willing to treat you as my (almost) equals and share (somewhat) the rule over your own kingdom. Aren’t you glad?

Let me give a modern parallel. The average non-native American doesn’t get why American Indians, especially those from the plains, really hate Mount Rushmore. They tend to say things like, “But isn’t it an engineering marvel?” or “It honors our greatest presidents!” or “But you’re carving your own version with Crazy Horse!” (Yes, maybe as an answer to you jackasses who started messing with sacred land in the first place.)

The backstory that most don’t understand is that the Paha Sapa (Black Hills) are sacred land stolen for gold, which the US government then decided to carve with big white faces in the heart of Lakota land. It’s a gigantic Fuck You to Indian people that became a national park whose visitors tell us “to just get over it already.” As for those “great” presidents? Yeah, maybe Lincoln got the 15th Amendment passed, but he also gave away tons of native land—and go read up on the Dakota 38 he had executed. He looks a little less heroic. Ol’ Jefferson started the Indian Removal Act that Jackson would later implement, and Washington, when Indians inconveniently didn’t want to sell their land so the fledging US could move west, set about to “extirpate” them (his word). And oh, Teddy, yeah, he instituted National Parks, a number of which are direct steals of native sacred land (like the Paha Sapa). The only way that monument could be MORE insulting to indigenous America would have been to put Andrew Jackson up there too.

Alexander’s burning of Persepolis was an ancient Mount Rushmore. And he was just as confused that the Persians didn’t want to forgive him even years later.

As Alexander went forward from the spring of 330, this disconnect between how he thought peoples ought to welcome him, and how they actually did, just got worse—especially as he moved into areas only tangentially under Persian control.

The people he conquered didn’t welcome conquest, nor did they want his “civilizing,” thank you very much. Alexander hadn’t really tried to impose Greek culture on Egypt, nor Babylon, nor Persia. In fact, Alexander used both Egyptian and Persian royal style to help legitimize his reign as King of Asia. But who were these Baktrian barbaroi, and Sogdians…and Indians? Can’t they see our superior ways and submit to join the Grand Asian Empire of Alexander? When this generous offer is rejected—because the invader isn’t regarded as All That by the invaded—it’s a shock to the system of perceived privilege.

This is what I mean by Conqueror’s/Colonialist Disease. And the more successful Alexander became, the worse it got. He was thrilled when people trembled at the sound of his name, and then submitted. It was proof of his superiority. Early in his career, he was still involved in proving it, but by the time he’d reached India, resistance wasn’t a challenge, it was an insult. How dare they?

This is why he grew increasingly disillusioned and cynical. He was not being welcomed in the way he’d imagined. It led him to become increasingly vicious until terror became state policy for him, as well.

#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#ancient Persia#ancient Egypt#Neo-Assyria#colonialist attitudes#ethnocentrism#Mount Rushmore#burning Persepolis#Alexander the Great in India#asks

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of Achaemenid Iran 1A, Course I - Achaemenid beginnings 1A

Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

Tuesday, 27 December 2022

Outline

Introduction; Iranian Achaemenid historiography; Problems of historiography continuity; Iranian posterior historiography; foreign historiography; Western Orientalist historiography; early sources of Iranian History; Prehistory in the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia

1- Introduction

Welcome to the 40-hour seminar on Achaemenid Iran!

It is my intention to deliver a rather unconventional academic presentation of the topic, mostly implementing a correct and impartial conceptual approach to the earliest stage of Iranian History. Every subject, in and by itself, offers to every researcher the correct means of the pertinent approach to it; due to this fact, the personal background, viewpoints and thoughts or eventually the misperceptions and the preconceived ideas of an explorer should not be allowed to affect his judgment.

If before 200 years, the early Iranologists had the possible excuse of studying a topic on the basis of external and posterior historical sources, this was simply due to the fact that the Old Achaemenid cuneiform writing had not yet been deciphered. Still, even those explorers failed to avoid a very serious mistake, namely that of taking the external and posterior historical sources at face value. We cannot afford to blindly accept a secondary historical source without first examining intentions, motives, scopes and aims of it.

As the seminar covers only the History of the Achaemenid dynasty, I don't intend to add an introductory course about the History of the Iranian Studies and the re-discovery of Iran by Western explorers of the colonial powers. However, I will provide a brief outline of the topic; this is essential because mainstream Orientalists have reached their limits and cannot provide us with a real insight, eliminating the numerous and enduring myths, fallacies, and deliberately naïve approaches to Achaemenid Iran.

In fact, most of the specialists of Ancient Iran never went beyond the limitations set by the delusional Ancient 'Greek' (in reality: Ionian and Attic) literature about the Medes and the Persians (i.e. the Iranians), because they never offered themselves the task to explain the reasons for the aberration that the Ancient Ionian and Attic authors created in their minds and wrote in their texts about Iran. This was utterly puerile and ludicrous.

And this brings us to the other major innovation that I intend to offer during this seminar, namely the proper, comprehensive contextualization of the research topic, i.e. the History of Achaemenid Iran. To give some examples in this regard, I would mention

a - the tremendous, multilayered and multifaceted impact of the Mesopotamian World, Civilization and Heritage on the formation of the Achaemenid Empire of Iran, and more specifically, the determinant role played by the Sargonid Empire of Assyria on the emergence of the first Empire on the Iranian plateau;

b - the ferocious opposition of the Mithraic Magi to the Zoroastrian Achaemenid court;

c - the involvement of the Anatolian Magi in the misperception of Iran by the Ancient Greeks; and

d- the utilization of the Ancient Greek cities by the Anti-Iranian side of the Egyptian priesthoods, princes and administrators.

To therefore introduce the proper contextualization, I will expand on the Neo-Assyrian Empire and the Sargonid times, not only to state the first mentions of the Medes and the Persians in History, but also to show the importance attributed by the Neo-Assyrian Emperors to the Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau, as well as the numerous peoples, settled or nomadic, who inhabited that region.

There is an enormous lacuna in the Orientalist disciplines; there are no interdisciplinary studies in Assyriology and Iranology. This plays a key role in the misperception of the ancient oriental civilizations and in the mistaken evaluation (or rather under-estimation) of the momentous impact that they had on the formation of the World History. There are no isolated cultures and independent civilizations as dogmatic and ignorant Western archaeologists pretend.

Only if one studies and evaluates correctly the colossal impact of the Ancient Mesopotamian world on Iran, can one truly understand the Achaemenid Empire in its real dimensions.

2- Iranian Achaemenid historiography

A. Achaemenid imperial inscriptions produced on solemn occasions

Usually multilingual texts written by the imperial scribes of the emperors Cyrus the Great, Darius I the Great, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, Darius II, Artaxerxes II, and Artaxerxes III, as well as of the ancestral rulers Ariaramnes and Arsames.

Languages and writing systems:

- Old Achaemenid Iranian (cuneiform-alphabetic; the official imperial language)

- Babylonian (cuneiform-syllabic; to offer a testimony of historical continuity and legitimacy, following the Conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great, who presented himself as king of Babylon)

- Elamite (cuneiform-logo-syllabic; to portray the Persians in particular as the heirs of the ancient land of Anshan and Sushan that the Assyrians and the Babylonians named 'Elam' and the indigenous population called 'Haltamti' / The first Achaemenid to present himself as 'king of Anshan' is Cyrus the Great and the reference is found in his Cylinder unearthed in Babylon.)

and

- Egyptian Hieroglyphic (if the inscription or the monument was produced in Egypt, since the Achaemenids were also pharaohs of Egypt, starting with Kabujiya/Cambyses)

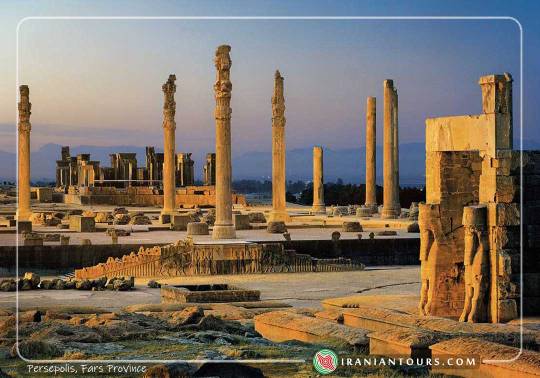

Imperial inscriptions are found in: Babylon (Cyrus Cylinder), Pasargad, Behistun, Hamadan, Ganj-e Nameh, Persepolis, Naqsh-e Rustam, Susa, Suez (Egypt), Gherla (Romania), Van (Turkey), and on various items

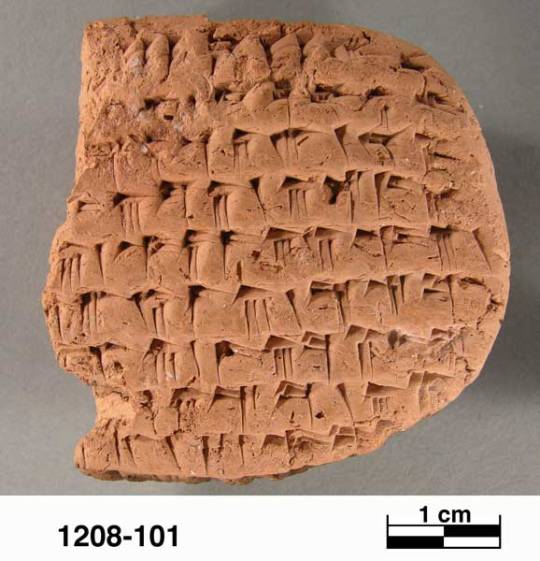

B. Persepolis Administrative Archives

This consists in an enormous documentation that has not yet been fully studied; it is not written in Old Achaemenid as one could expect but mainly in Elamite cuneiform. It consists of two groups, namely

- the Persepolis Fortification Archive, and

- the Persepolis Treasury Archive.

The Persepolis Fortification Archive was unearthed in the fortification area, i.e. the northeastern confines of the enormous platform of the Achaemenid capital Parsa (Persepolis), in the 1930s. It comprises of more than 30000 tablets (fragmentary or entire) that were written in the period 509-494 BCE (at the time of Darius I). The tablets were written in Susa and other parts of Fars and the territory of the ancient kingdom of Elam that vanished in the middle of the 7th c. (more than 130 years before these texts were written). Around 50 texts had Aramaic glosses. More than 2000 tablets have been published and translated. These texts are records of transactions, distribution of food, provisioning of workers, transportation of commodities, etc.; few tablets were written in other languages, namely Old Iranian (1), Babylonian (1), Phrygian (1) and Greek (1).

The Persepolis Treasury Archive was found in the northeastern room of the Treasury of Xerxes. It contains more than 750 tablets and fragments (in Elamite) and more than 100 have been published. They all date back in period 492-458 BCE. These tablets are either letters or memoranda dispatched by imperial officials to the head of the Treasury; they concern the payment of workmen, the issue of silver, and other administrative procedures. Only one tablet was written in Babylonian.

The entire documentation offers valuable information as regards the function of various imperial services, namely the couriers, the satraps, the imperial messengers, the imperial storehouse, etc. The archives shed light on the origin of the imperial administrators, as ca. 1900 personal names have been recorded: 10% were Elamites (who had apparently survived for long far from their country after the destruction of Susa by Assurbanipal (640 BCE), fewer were Babylonians, and the outright majority consisted of Iranians (Persians, Medes, Bactrians, Sakas, Arians, etc.).

C. Imperial Aramaic

The diffusion of the use of Aramaic started already in the Neo-Assyrian times and during the 7th c. BCE; the creation of the 'Royal Road', the systematization of the transportation, the improvement of communications, and the formation of the network of land-, sea- and desert routes that we now call 'Silk-, Spice- and Perfume- Road' during the Achaemenid times helped further expand the use of Aramaic. The linguistic assimilation of the Babylonians, the Jews and the Phoenicians with the Aramaeans only strengthened the diffusion of the Aramaic, which became the second international language ('lingua franca') in the History of the Mankind (after the Akkadian / Assyrian-Babylonian). Gradually, Aramaic became an official Achaemenid language after the Old Achaemenid Iranian.

Except the Aramaic texts attested in the Persepolis Administrative Archives, thousands of Aramaic texts of the Achaemenid times shed light onto the society, the economy, the administration, the military organization, the trade, the religions, the cults, the culture and the spirituality attested in various provinces of the Iranian Empire. At this point, only indicatively, I mention few significant groups of texts:

- the Elephantine papyri and ostraca (except Aramaic, they were written in Hieratic and Demotic Egyptian, Coptic, Alexandrian Koine, and Latin) – 5th and 4th c. BCE,

- the Hermopolis Aramaic papyri,

- the Padua Aramaic papyri, and

- the Khalili Collection of Aramaic Documents from Bactria (48 texts written on leather, papyrus, stone or clay, dating from the period 353-324 BCE, and mainly from the reign of Artaxerxes III whereas the most recent dates from the reign of Alexander the Great).

Here I have to add that the widespread use of Imperial Aramaic and its use as a second official language for Achaemenid Iran brought an end to the use of the Elamite (in the middle of the 5th c.) and, after the end of the Achaemenid dynasty and the split of the state of Alexander the Great, contributed to the formation of two writing systems, namely Parthian and Pahlavi which were in use during the Arsacid and the Sassanid times. Imperial Aramaic helped establish many other writing systems, but this goes beyond the limits of the present seminar.

3- Problems of historiography continuity

There are no historical references to the Achaemenid dynasty made at the time of the Arsacids (Ashkanian: 250 BCE-224 CE) and the Sassanids 224-651 CE); this situation is due to many factors:

- the prevalence of another Iranian nation of probably Turanian origin, namely the Parthians and the Arsacid dynasty,

- the rise of the anti-Achaemenid, anti-Zoroastrian Magi who tried to impose Mithraism throughout Iran during the Arsacid times,

- the formation of an oral epic tradition and the establishment of a legendary historiography about the pre-Arsacid past during the Sassanid times, and

- the scarcity of written sources and the terrible destructions that occurred in Iran during the Late Antiquity, the Islamic era, and the Modern times (early Islamic conquests, divisions of the Abbasid times, Mongol invasions, Safavid-Ottoman wars, Western colonial looting, etc.).

This situation raised Western academic questions of Iranian identity, continuity, and historicity. But this attempt is futile. Iranian historiography of Islamic times shows that these questions were fully misplaced.

4- Iranian posterior historiography (Iranian historiography of Islamic times)

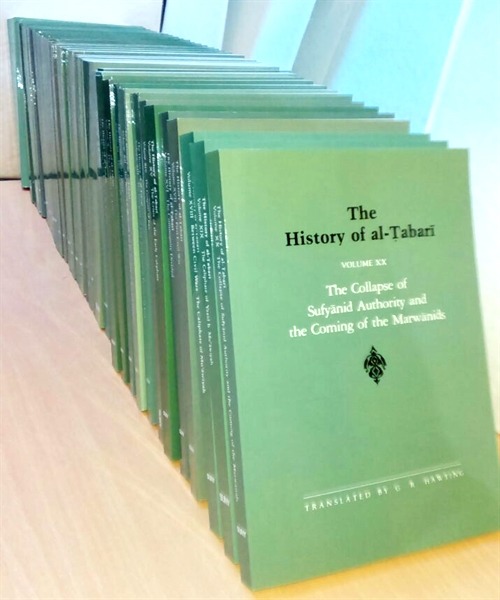

With Tabari (839-923) and his voluminous History of Prophets and Kings we realize that there were, in spite of the destructions caused because of the Islamic conquests, historical documents on which he was based to expand about the Sassanid dynasty; actually one out of the 40 volumes of the most recent translation of Tabari to English (published by the State University of New York Press from 1985 through 2007) is dedicated to the History of Sassanid Iran (vol. 5). And the previous volume (vol. 4) covers the History of Achaemenid and Arsacid Iran, Alexander the Great, Nabonid Babylonia, Assyria and Ancient Israel and Judah.

Other important Iranian historians of the Islamic times, like Abu'l-Fadl Bayhaqi (995-1077), Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247-1318) who wrote the truly first World History, Alaeddin Aṭa Malik Juvaynī (1226-1283), and Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi (ca. 1370-1454), did not expand much on pre-Islamic periods as the focus of their writing was on contemporaneous developments.

However, the aforementioned historians and all the authors, who are classified in this category, represent only one dimension of Iranian historiography of Islamic times. A totally different approach and literature have been illustrated by Ferdowsi's Shahnameh (Book of Kings). Abu 'l Qasem Ferdowsi (940-1025) was not the first to compose an epic in order to standardize in mythical terms and legendary concepts the pre-Islamic Iranian past; but he was the most successful and the most illustrious. That is why many other epic poets followed his example, notably the Azeri Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1209) and the Turkic Indian Amir Khusraw (1253-1325).

Within the context of this poetical historiography, historical emperors of pre-Islamic Iran appear as legendary figures only to be then viewed as materialization of divine patterns. The origin of this transcendental historiography seems to be retraced in the Sassanid times, but all the major themes are clearly of Zoroastrian identity and can therefore be attributed to the Achaemenid world perception and world conceptualization.

It is essential at this point to state that, until the imposition of modern Western colonial academic and educational standards in Iran, Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and the corpus of Iranian legendary historiography was the backbone of the Iranian cultural, intellectual and educational identity.

It is a matter of academic debate whether an original text named Khwaday-Namag, written during the Sassanid times, and now lost, is at the very origin of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and of the Iranian legendary historiography. The 19th c. German Orientalist Theodor Nöldeke is credited with this theory that has not yet been proved.

All the same, the spiritual standards of this approach are detected in the Achaemenid times.

5- Foreign historiography

Ancient Greek (in reality, Ionian and Attic), Ancient Hebrew and Latin sources of Achaemenid History exist, but first they are external, second they appear to be posterior in their largest part, and third they often bear witness to astounding inaccuracies, fables, untrustworthy data, misplaced focus, excessive verbosity without real substance, and -above all- an enormous and irreconcilable misunderstanding of the Iranian Achaemenid reality, values, world view, mindset, and behavior.

The Ancient Hebrew sources shed light on issues that were apparently critical to the tiny and unimportant, Jewish minority of the Achaemenid Empire; however, these Biblical narratives concern facts that were absolutely insignificant to the imperial authorities of Parsa. One critical issue is concealed by modern scholars though; although all the nations of the Empire were regularly mentioned in the Achaemenid inscriptions and depicted on bas reliefs, the Jews were not. This undeniable fact irrevocably conditions the supposed 'importance' of Biblical texts like Ezra, Esther, Nehemiah, etc. All the same, these foreign historical sources are important for the Jews.

The Ionian and Attic accounts of events that were composed by the Carian renegade Herodotus, the Dorian Ctesias, and the Athenian Xenophon present an even more serious problem. They happened to be for many centuries (16th – 19th c.) the bulk of the historical documentation that Western European academics had access to as regards Achaemenid Iran. This situation produced grave biases among Western academics, because they took all these sources at face value since they had no access to original documentation. The grave trouble persisted even after the decipherment of the Old Achaemenid cuneiform writing and the archaeological excavations that brought to daylight original Iranian imperial documentation.

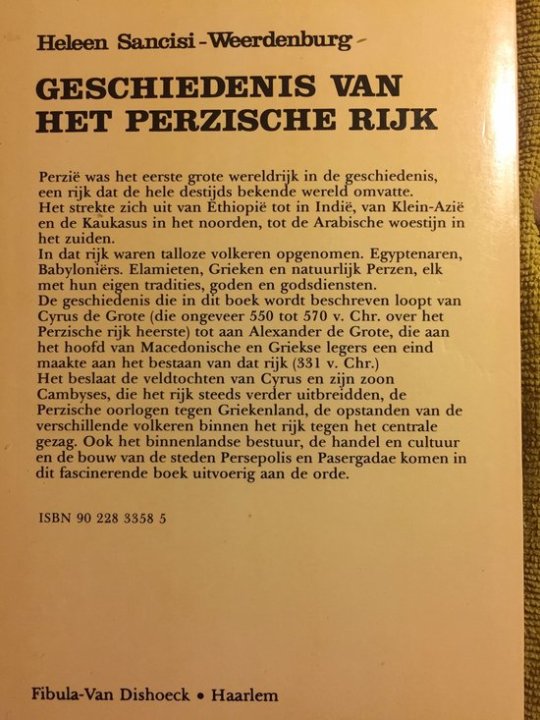

Only recently, at the end of the 20th c., leading Iranologists like Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg started criticizing the absolutely delusional History of Achaemenid Iran that modern Western scholars were producing without even understanding it by foolishly accepting Ancient Ionian myths, lies and propaganda against the Iranian Empire at face value. This grave problem had also two other parameters:

- first, there was an enormous gap of civilization and a tremendous cultural difference between the Iranian imperial world view, the spiritual valorization of the human being, and the Zoroastrian monotheism from one side and the chaotic, disorderly and profane elements of the western periphery of the Empire. The so-called Greek tribes in Western Anatolia and in the South Balkans were not only multi-divided and plunged in permanent conflict; they were also extremely verbose on common issues, they desecrated the divine world with their nonsensical myths and puerile narratives, and they defiled human spirituality with their love stories about their pseudo-gods. But, very arbitrarily and quite disastrously, the so-called Ancient Greek civilization had been erroneously taken as 'classics' by modern Europeans at a time they had no access to Ancient Oriental sources.

- second, the vertical differentiation between Imperial Iran as the blessed land of divine mission and the disunited and peripheral lands of conflict, discord and strife that were inhabited by the Greek tribes was reflected on the respective, impressively different types of historiography; to the Iranians, few words written by anonymous scribes were enough to describe the groundbreaking deeds of divinely appointed rulers. But for the Greeks, the useless rumors, the capricious hearsay, the intentional lie, the nefarious expression of their complex of inferiority, the vicious slander, and the deliberate ignominy 'had' to be recorded and written down.

The fact that Herodotus' and Xenophon's long narratives have long been taken as the basic source of information about Achaemenid Iran demonstrates how disoriented and misplaced modern Western scholarship is. But by preferring to rely mainly on the Ancient Greek lengthy and false narratives, and not on the succinct, true and chaste Old Achaemenid Iranian inscriptions, they totally misrepresent Ancient Iranian History, preposterously extrapolating later and corrupt standards to earlier and superior civilizations.

And whereas Ancient Roman authors, who wrote in Latin (Pliny the Elder, Seneca the Younger, etc.), and Jewish or Christian historians, who wrote in Alexandrine Koine, like Flavius Josephus and Eusebius of Caesarea Maritima, reproduced the style of lengthy narratives that turns History to mere gossip, the great Babylonian scholar Berossus was very reluctant to add personal comments to his original sources or to allow subjective considerations and thoughts to contaminate his text.

In any case, the vast issue of the multilayered damages caused by the untrustworthy Ancient Greek historiography to modern Western academics' perception and interpretation of Achaemenid Iran is a topic that deserves an entirely independent seminar.

--------------

To watch the video (with more than 110 pictures and maps), click the links below:

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN - Achaemenid beginnings 1Α

By Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

youtube

------------------------

To listen to the audio, clink the links below:

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN - Achaemenid beginnings 1 (a+b)

------------------------------

Download the text in PDF:

#Achaemenid dynasty#Achaemenid History#Ariaramnes#Arsacid#Arsames#Artaxerxes I#Artaxerxes II#Artaxerxes III#Assyria#Assyriology#Babylon#Babylonia#Babylonian#Berossus#Cambyses#Ctesias#cuneiform#Cyrus the Great#Darius I the Great#Darius II#Elam#Elamite#Elephantine papyri#Esther#Ezra#Ferdowsi#Ganj-e Nameh#Gherla#Hamadan#Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN

Tentative diagram of the 40-hour seminar

(in 80 parts of 30 minutes)

Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

Tuesday, 27 December 2022

--------------------------

To watch the videos, click here:

https://www.patreon.com/posts/history-of-iran-76436584

To hear the audio, click here:

-------------------------------------------

1 A - Achaemenid beginnings I A

Introduction; Iranian Achaemenid historiography; Problems of historiography continuity; Iranian posterior historiography; foreign historiography

1 B - Achaemenid beginnings I B

Western Orientalist historiography; early sources of Iranian History; Prehistory in the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia

2 A - Achaemenid beginnings II A

Brief Diagram of the History of the Mesopotamian kingdoms and Empires down to Shalmaneser III (859-824 BCE) – with focus on relations with Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau

2 B - Achaemenid beginnings II B

The Neo-Assyrian Empire from Shalmaneser III (859-824 BCE) to Sargon of Assyria (722-705 BCE) – with focus on relations with Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau

3 A - Achaemenid beginnings III A

From Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) to Assurbanipal (669-625 BCE) to the end of Assyria (609 BCE) – with focus on relations with Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau

3 B - Achaemenid beginnings III B

The long shadow of the Mesopotamian Heritage: Assyria, Babylonia, Elam/Anshan, Kassites, Guti, Akkad, and Sumer / Religious conflicts of empires – Monotheism & Polytheism

4 A - Achaemenid beginnings IV A

The Sargonid dynasty and the Divine, Universal Empire – the Translatio Imperii

4 B - Achaemenid beginnings IV B

Assyrian Spirituality, Monotheism & Eschatology; the imperial concepts of Holy Land (vs. barbaric periphery) and Chosen People (vs. barbarians)

5 A - Achaemenid beginnings V A

The Medes from Deioces to Cyaxares & Astyages

The early Achaemenids (Achaemenes & the Teispids)

5 B - Achaemenid beginnings V B

- Why the 'Medes' and why the 'Persians'?

What enabled these nations to form empires?

6 A - Zoroaster A

Shamanism-Tengrism; the life of Zoroaster; Avesta and Zoroastrianism

6 B - Zoroaster B

Mithraism vs. Zoroastrianism; the historical stages of Zoroaster's preaching and religion

7 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) I A

The end of Assyria, Nabonid Babylonia, and the Medes

7 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) I B

The Nabonidus Chronicle

8 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) II A

Cyrus' battles against the Medes

8 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) II B

Cyrus' battles against the Lydians

9 Α - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) III A

The Battle of Opis: the facts

9 Β - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) III B

Why Babylon fell without resistance

10 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) IV A

Cyrus Cylinder: text discovery and analysis

10 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) IV B

Cyrus Cylinder: historical continuity in Esagila

11 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) V A

Cyrus' Empire as continuation of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

11 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) V B

Cyrus' Empire and the dangers for Egypt

12 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) VI A

Death of Cyrus; Tomb at Pasargad

12 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) VI B

Posterity and worldwide importance of Cyrus the Great

13 A - Cambyses I A

Conquest of Egypt and Cush (Ethiopia: Sudan)

13 B - Cambyses I B

Iran as successor of Assyria in Egypt, and the grave implications of the Iranian conquest of Egypt

14 A - Cambyses II A

Cambyses' adamant monotheism, his clash with the Memphitic polytheists, and the falsehood diffused against him (from Egypt to Greece)

14 B - Cambyses II B

The reasons for the assassination of Cambyses

15 A - Darius the Great I A

The Mithraic Magi, Gaumata, and the usurpation of the Achaemenid throne

15 B - Darius the Great I B

Darius' ascension to the throne

16 A - Darius the Great II A

The Behistun inscription

16 B - Darius the Great II B

The Iranian Empire according to the Behistun inscription

17 A - Darius the Great III A

Military campaign in Egypt & the Suez Canal

17 B - Darius the Great III B

Babylonian revolt, campaign in the Indus Valley

18 A - Darius the Great IV A

Darius' Scythian and Balkan campaigns; Herodotus' fake stories

18 B - Darius the Great IV B

Anti-Iranian priests of Memphis and Egyptian rebels turning Greek traitors against the Oracle at Delphi, Ancient Greece's holiest shrine

19 A - Darius the Great V A

Administration of the Empire; economy & coinage

19 B - Darius the Great V B

World trade across lands, deserts and seas

20 A - Darius the Great VI A

Rejection of the Modern European fallacy of 'Classic' era and Classicism

20 B - Darius the Great VI B

Darius the Great as the end of the Ancient World and the beginning of the Late Antiquity (522 BCE – 622 CE)

21 A - Achaemenids, Zoroastrianism, Mithraism, and the Magi A

Avesta and the establishment of the ideal empire

21 B - Achaemenids, Zoroastrianism, Mithraism, and the Magi B

The ceaseless, internal strife that brought down the Xšāça (: Empire)

22 A - The Empire-Garden, Embodiment of the Paradise A

The inalienable Sargonid-Achaemenid continuity as the link between Cosmogony, Cosmology and Eschatology

22 B - The Empire-Garden, Embodiment of the Paradise B

The Garden, the Holy Tree, and the Empire

23 A - Xerxes the Great I A

Xerxes' rule; his upbringing and personality

23 B - Xerxes the Great I B

Xerxes' rule; his imperial education

24 A - Xerxes the Great II A

Imperial governance and military campaigns

24 B - Xerxes the Great II B

The Anti-Iranian complex of inferiority of the 'Greek' barbarians (the so-called 'Greco-Persian wars')

25 A - Parsa (Persepolis) A

The most magnificent capital of the pre-Islamic world

25 B - Parsa (Persepolis) B

Naqsh-e Rustam: the Achaemenid necropolis: the sanctity of the mountain; the Achaemenid-Sassanid continuity of cultural integrity and national identity

26 A - Iran & the Periphery A

Caucasus, Central Asia, Siberia, Tibet and China Hind (India), Bengal, Deccan and Yemen

26 B - Iran & the Periphery B

Sudan, Carthage and Rome

27 A - The Anti-Iranian rancor of the Egyptian Memphitic priests A

The real cause of the so-called 'Greco-Persian wars', and the use of the Greeks that the Egyptian Memphitic priests made

27 B - The Anti-Iranian rancor of the Egyptian Memphitic priests B

Battle of the Eurymedon River; Egypt and the Wars of the Delian League

28 A - Civilized Empire & Barbarian Republic A

The incomparable superiority of Iran opposite the chaotic periphery: the Divine Empire

28 B - Civilized Empire & Barbarian Republic B

Why the 'Greeks' and the Romans were unable to form a proper empire

29 A - Artaxerxes I (465-424 BCE) A

Revolt in Egypt; the 'Greeks' and their shame: they ran to Persepolis as suppliants

29 B - Artaxerxes I (465-424 BCE) B

Aramaeans and Jews in the Achaemenid Court

30 A - Interregnum (424-403 BCE) A

Xerxes II, Sogdianus, and Darius II

30 B - Interregnum (424-403 BCE) B

The Elephantine papyri and ostraca; Aramaeans, Jews, Phoenicians and Ionians

31 A - Artaxerxes II (405-359 BCE) & Artaxerxes III (359-338 BCE) A

Revolts instigated by the Memphitic priests of Egypt and the Mithraic subversion of the Empire

31 B - Artaxerxes II (405-359 BCE) & Artaxerxes III (359-338 BCE) B

Artaxerxes II's capitulation to the Magi and the unbalancing of the Empire / Cyrus the Younger

32 A - Artaxerxes IV & Darius III A

The decomposition of the Empire

32 B - Artaxerxes IV & Darius III B

Legendary historiography

33 A - Alexander's Invasion of Iran A

The military campaigns

33 B - Alexander's Invasion of Iran B

Alexander's voluntary Iranization/Orientalization

34 A - Alexander: absolute rejection of Ancient Greece A

The re-organization of Iran; the Oriental manners of Alexander, and his death

34 B - Alexander: absolute rejection of Ancient Greece B

The split of the Empire; the Epigones and the rise of the Orientalistic (not Hellenistic) world

35 A - Achaemenid Iran – Army A

Military History

35 B - Achaemenid Iran – Army B

Achaemenid empire, Sassanid militarism & Islamic Iranian epics and legends

36 A - Achaemenid Iran & East-West / North-South Trade A

The development of the trade between Egypt, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Iran, Turan (Central Asia), Indus Valley, Deccan, Yemen, East Africa & China

36 B - Achaemenid Iran & East-West / North-South Trade B

East-West / North-South Trade and the increased importance of Mesopotamia and Egypt

37 A - Achaemenid Iran: Languages and scripts A

Old Achaemenid, Aramaic, Sabaean and the formation of other writing systems

37 B - Achaemenid Iran: Languages and scripts B

Aramaic as an international language

38 A - Achaemenid Iran: Religions A

Rise of a multicultural and multi-religious world

38 B - Achaemenid Iran: Religions B

Collapse of traditional religions; rise of religious syncretism

39 A - Achaemenid Iran: Art and Architecture A

Major archaeological sites of Achaemenid Iran

39 B - Achaemenid Iran: Art and Architecture B

The radiation of Iranian Art

40 A - Achaemenid Iran: Historical Importance A

The role of Iran in the interconnection between Asia and Africa

40 B - Achaemenid Iran: Historical Importance B

The role of Iran in the interconnection between Asia and Europe

--------------------------------------

Download the diagram here:

#Achaemenid#Megalommatis#Ancient Iran#Old Achaemenid#Persia#Persians#Media#Orientalism#Medes#History of Ancient Iran

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashurbanipal: the Coming King – Part II (1987)

Ashurbanipal: the Coming King - Part II

In this 2-series article (published back in 1987), I present a brief diagram of the Messianic Assyrian dynasty of the Sargonids (722-609 BCE), who ruled Nineveh as the exemplary universal empire of the World History; accepting Jonah's preaching, Sargon of Assyria (722-705 BCE) and his son and grandson, Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) and Esarhaddon (681-670 BCE), ushered the world to the Messianic Era of Ashurbanipal (669-625 BCE), who lived a first life as the Suffering Messiah, on the basis of contemporaneous historical texts and personal declarations, only to leave to posterity the claim to his exulted return and celestial reign. All posterior adaptations and identifications being fraudulent, the Second Coming of Ashurbanipal is instantly corroborated by the nature of his magnum opus. The two titles of the series are: "Ashurbanipal: the Righteous Suffering" and "Ashurbanipal: the Coming King".

Ашурбанипал: грядущий царь - Часть ΙI

В этой 2-серийной статье (опубликованной еще в 1987 г.) я представляю краткую схему мессианской ассирийской династии Саргонидов (722-609 гг. до н. э.), правивших Ниневией как образцовой универсальной империей Всемирной истории; приняв проповедь Ионы, Саргон Ассирийский (722-705 гг. до н.э.) и его сын и внук Сеннахирим (705-681 гг. до н.э.) и Асархаддон (681-670 гг. до н.э.), открыли миру мессианскую эру Ашшурбанипала (669–625 гг. до н. э.), который прожил первую жизнь как Страдающий Мессия, на основании современных ему исторических текстов и личных заявлений, только для того, чтобы оставить потомкам притязания на его ликующее возвращение и небесное правление. Все последующие а��аптации и отождествления являются мошенническими, и Второе пришествие Ашшурбанипала немедленно подтверждается характером его великого произведения. Два названия сериала: «Ашурбанипал: Праведный Страдающий » и «Ашурбанипал: грядущий царь».

Ασσουρμπανιπάλ Ερχόμενος – Τμήμα Β'

Σε αυτή την σειρά δύο άρθρων (δημοσιευμένων το 1987), παρουσιάζω ένα σύντομο διάγραμμα της Μεσσιανικής Ασσυριακής δυναστείας των Σαργονιδών (722-609 πτεμ), οι οποίοι κυβέρνησαν τη Νινευή ως την υποδειγματική παγκόσμια αυτοκρατορία της Παγκόσμιας Ιστορίας. Αποδεχόμενοι το κήρυγμα του Ιωνά, ο Σαργών της Ασσυρίας (722-705 π.Χ.), καθώς και ο υιός και εγγονός του, Σεναχειρίμπ (705-681 πτεμ) και Ασσαρχαδδών (681-670 πτεμ), οδήγησαν τον κόσμο στη Μεσσιανική Εποχή του Ασουρμπανιπάλ (669-625 πτεμ), ο οποίος έζησε μια πρώτη ζωή ως ο Πάσχων Μεσσίας, με βάση τα σύγχρονα τότε ιστορικά κείμενα και τις προσωπικές του διακηρύξεις, μόνο για να αφήσει σε όλους τους επόμενους την αξίωση για την εξυμνηθείσα επιστροφή του και την ουράνια βασιλεία του. Καθώς όλες οι μεταγενέστερες προσαρμογές του θέματος και ταυτίσεις προσώπων είναι ολότελα δόλιες, η Δευτέρα Παρουσία του Ασουρμπανιπάλ επιβεβαιώνεται ακαριαία από τη φύση του μεγάλου έργου του. Οι δύο τίτλοι της σειράς είναι: «Ασσουρμπανιπάλ Πάσχων» και «Ασσουρμπανιπάλ Ερχόμενος».

-------------------------------

Main units:

Introduction

The flight of the Assyrians and of the ten tribes of Israel

The exile and the return

Ashurbanipal as the Coming King

Ashurbanipal - the Righteous Suffering

Appendices:

Assyria and Nomads

Assyrians, Medes and Urartu

in: Inexplicable, February 1987, pp. 44-54

----------------------

Основные главы:

Введение

Бегство ассирийцев и десяти колен Израилевых

Изгнание и возвращение

Ашшурбанипал как грядущий царь

Ашшурбанипал – Праведный Страдающий

Приложения:

Ассирия и кочевники

Ассирийцы, Мидийцы и Урарту

в: Необъяснимое, февраль 1987 г., стр. 44-54

--------------------------

Κυρίως ενότητες:

Εισαγωγή

Η φυγή των Ασσυρίων και των δέκα φυλών του Ισραήλ

Η μετοικεσία και η επιστροφή

Ο Ασσουρμπανιπάλ ως Ερχόμενος

Ο Ασσουρμπανιπάλ-Πάσχων

Παραρτήματα:

Ασσυρία και Νομάδες

Ασσύριοι, Μήδοι και Ουραρτού

στο Ανεξήγητο, Φεβρουάριος 1987, σ. 44-54

--------------------

Κατεβάστε το άρθρο: / Download the article: / Скачать статью:

issuu

#Assyria#Assurbanipal#ashurbanipal#Sargon of Assyria#Aramaeans#Ten tribes of Israel#Ancient Israel#Judah#Babylonia#Sennacherib#Esarhaddon#Ασσουρμπανπάλ#Ασσυρία#Βαβυλώνα#Μεσοποταμία#Σαργωνίδες#Σαργώνας#Σεναχειρίμπ#Δέκα φυλές του Ισραήλ#Μεσσίας

0 notes

Note

What did Alexander’s soldiers think of him and the campaigns, towards the end? How do you think they felt about his death?

I think it varied a lot. There are several factors, depending on WHO, and when they joined the campaign.

By the time of his death, Alexander’s army consisted of veterans from his father’s army, younger soldiers who’d signed up when he left or joined as reinforcement at various points during his campaigns, Greek mercenaries hired at various points, as well as non-Macedonian/non-Greek soldiers from Asia, especially Persian contingents such as the 30,000 Epigoni, who stirred up such resentment among Macedonians. (Also, keep in mind that about half the Macedonian army remained in Macedonia to support Antipatros as regent, so they were not “Alexander’s men” to nearly the same degree.)

Alexander’s Persianizing presented a problem for traditional Macedonians (and Greeks). Whether he adopted some Persian court customs out of necessity, or ideology (or both), that didn’t sit well with many of his non-Asian followers.

We can’t forget that traditional Macedonians viewed themselves as superior, not only to the Persians and other “Asiatics,” but even to the Greeks, who they viewed as weak and divided. They were under the impression that they’d go over there, beat the crap out of the Persians, loot everything, and come home rich. They were nativists, and if there had been “Make Macedonia Great Again” red hats for them to wear, as Alexander increasingly added Persian-esque elements to the court, they’d have been marching around in them. Those who want to bitch about Alexander ignoring the wishes of his soldiers need to remember that. The wishes of his soldiers was either to take all the wealth and go home, or to rule Persia with an iron fist and milk everything they could, ala the Assyrians. Look how that ended for the Sargonids.

We’re told that on his deathbed, Alexander had a hole knocked in one wall so men could parade past, allowing him to say goodbye. (They came in through the door and out through the hole in the wall, it seems.) And the men came. He greeted and nodded to them, recognizing them. These were apparently the Macedonian troops who’d been with him for years. If they had mixed feelings about the Persianizing, they came to see him. Similarly, one reason not to call the Indian incident or Opis a “mutiny” is that mutinies end with the leader dead. They wanted him to turn around; they didn’t want to get rid of him. Beth Carney’s “indiscipline” is a better term. (I’ve also seen “insurrection” used, but like “mutiny,” I think it too strong.)

After his death, factions immediately developed and a lot of the Persian aspects of Alexander’s reign were jettisoned, including the Persian wives, with a couple notable exceptiosn: Seleukos and Peukestis, who kept them for obvious reasons (they were ruling over areas with large Persian populations). Most of the rulers in Asia Minor, Egypt, and Greece/Macedonia/Thrace returned to Greek/Macedonian wives, and their methods of rule were, at most, “Asian tinged,” rather than heavily influenced.

My sense is that most of his soldiers liked Alexander’s victories, and their new enormous wealth, but they didn’t like the Persians or Persianizing.

This is not especially surprising in the ancient world. Again, remember the VERY STRONG “anti-mixing” sentiment among Greeks.

Plato (et al.) argued the Athenians were MOST pure not only for being autochthonous (native to Attica/always there), but by not mixing with other Greeks due to Perikles’ citizenship law (had to have BOTH parents Athenian to be a citizen). That’s “double-purity,” ha. They didn’t have “barbarian blood,” and they weren’t immigrants to Attica, either! That gave them a leg up over even the Spartans, who could argue no-mixing, but were still immigrants, however far back.

(Whether ANY of that is true is completely irrelevant to what they believed. The Dorian invasion may be a myth, but it was one they accepted, just like they believed in the autochthonous origin of the Athenians.)

That demonstrates how concerned Greeks were with “mixing.” Even immigrants (metics, in Athens) were suspect; couldn’t be trusted to defend the homeland like a native-born son. A lot of those attitudes have transferred down through time (via Rome, then the Enlightenment) to fuel modern anti-immigrant and Purity ideologies.

And it’s not just Greeks. The Persians were the same. A glass ceiling existed in Persia. The king might marry women from everywhere…but only a pure Persian could be mother to the heir. Satraps might be concessions to keep the local peace, but only Persians could occupy the highest offices at court, including regional governors, etc. And don’t get me started on Egyptians, especially in the Bronze Age. Or the Romans later. LOL.

Ethnocentrism was simply How We See the World.

If we can’t make Alexander into Tarn’s “One World” advocate, he did stand against the Platonic-Aristotelian ideas that “mixing” was bad. In his case, it was driven by practicality—he had to rule a mixed empire and avoid constant rebellion (like the Assyrians had experienced with their hard-line Assyrianizing of provinces)—but also a little based on his experiences, which called into question the philosophical ideas of Plato, Aristotle, and Isokrates. I’m reminded of Caesar’s ideas about the Gauls, which diverged from the ideological philosophic notions of Seneca. Caesar avoided geographical determinism, preferring notions of diet and custom instead. Like Alexander, Caesar had pragmatic, boots-on-the-ground experience with the people he was writing about, not second- and third-hand ethnographic accounts that were more about stereotypes and literary topoi than actual reports.

Anyway, a lot of Alexander’s soldiers liked “the winning” (to sound Trumpesque), but not his attitudes towards “them furriners.” They were happy to jettison the more radical changes he’d made after his death.

#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#ancient Greece#Greek ethnographic ideas#Greek ethnocentrism#Plato#Aristotle#ancient proto-racism#Macedonian soldiers#racism in the ancient world#asks

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello. First of all thank you for your blog. I really love reading all your replies. Second, can you maybe point me to some sources or just something about cults and sexuality/sexual practises in ancient rome (not sure if you even specialize in roman history) or anything from antiquity in general? I dont exactly know how to word it i hope you get what i mean and it doesnt sound weird. Have a good day (:

Like most ancient historians, I did study Roman history as a grad student, but I had a stronger focus on the Ancient Near East (especially Sargonid Assyria). At my uni, we have a Romanist too, so I’ve not needed to keep up as much on the Roman side.

But sexuality is one of my areas of specialty, so I do know a few names you may want to look at. First, is the mighty Marilyn Skinner. :-) Her Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture is now in it’s 2nd ed., I believe (I have the first). Also, David Fredrick has written on Roman gender and sexuality. So I’d start with those two and plumb their bibliographies for further material.

Hope that helps!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr Meme

I don’t necessarily post a lot about myself, and I’m not sure most people care that much. Ha. But all right, I’ll play along:

1. the meaning behind my url. It’s my name. Nothing exciting. The name on my actual Tumblr “Mathetria,” means “woman scholar” in ancient Greek.

2. a picture of me In my profile image.

3. tattoos i have 2: one is the Achemenid royal lion, the other, the Macedonian sunburst. At some point, I’d also like to get a Sargonid lamasu, and not just any, but one specific lamasu detroyed by Isis that used to guard Nineveh. Many of the things they destroyed were copies, but that one was real, so he’ll live on, on me.