#Slobodan River

Text

Eurovision 2004 - Number 39 - Slobodan River - "Surrounded"

youtube

They're back - the Ur band of Estonian Eurovision. After last year's experimentation with a televote at Eurolaul, ETV have flipped entirely and this year's competition is 100% televoted. Maybe the outcome of that advisory televote last year was chastening...

You would expect a band as big as well-known in Estonia as Slobodan River to benefit from that, but they are up against a couple of other big names in the competition, so they need a big song.

They've gone with Surrounded, a song about the final straw and telling him just get out. No more lines, excuses or threats, get out. There's an undercurrent of violence both in what lead singer Ithaka Maria has experienced and in what she'll do if her partner doesn't comply with her demand. The song is melodic pop-rock with alternative slant, and given the lyrics, is somewhat non-angry. It's a sing along fun song with an upbeat lilt.

This is all a bit Abba in fact. Even more so because Ithaka Maria and guitarist Tomi Rahula have been married for a while. In fact they've been a couple since she was 13 and he was 16 at high school in 1993. The band was formed with them at the centre with Maria writing many of the songs - this is one of hers. Slobodan River in 2004 are actually having their best year with their album (also called Surrounded) yielding many singles that got to the upper ends of the Estonian charts.

The band split two years later in 2006. Maria and Tomi divorced five years later in 2011. They all went on to much national success in different arenas (as I outlined in for their 2003 song What a Day). That makes this the last time that Slobodan River appeared together in the Estonian national final, but they'd all be back again either solo, as song-writers, in other bands or even as the producer for the entire show! I have no doubt that this blog bit will be linked to many times in the future.

#esc#esc 2004#eurovision#eurovision song contest#istanbul#istanbul 2004#Youtube#national finals#eurolaul 2004#Estonia#Slobodan River#Ithaka Maria#Tomi Rahula#Stig Rästa

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny was pronounced dead by the Russian prison service, most supporters of Russia’s liberal opposition plunged into despair.

Some spoke of a grappling fear from realization that they “are now left one on one with Putin,” while others claimed that with Navalny had died the hope for Russia’s democratic future.

But despite his heroism, Navalny wasn’t Russia’s only hope for democracy.

From the ousting of dictator Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia’s Bulldozer Revolution in 2000 to Ukraine’s 2014 Revolution of Dignity, the most successful nonviolent revolutionary movements in Russia’s neighborhood have been based on grassroots self-mobilization, driven forward not by a single leader, but a shared vision of a better tomorrow.

At least one such movement exists in Russia today.

Not in Moscow, but in Turkic-majority Bashkortostan.

Bashkortostan’s long-running, diverse, and fundamentally nonviolent protest movement might just be Russia’s greatest hope for democratic change right now. Yet, like other popular movements advocating for Indigenous rights and region-level democratization in Russia, it has been sidelined and gravely misinterpreted by Western observers, as well as policymakers who instead continue to favor engagements with Moscow-hailing mainstream Russian liberal opposition.

Russia’s most populous ethnic republic, Bashkortostan is located between the Volga River to the west and the Ural Mountains to the east. Bashkorts, the region’s Indigenous Kipchak Turkic ethnic group conquered by Russians in the 16th century, make up 31.5 percent of the republic’s population. Russians (37.5 percent) and Volga Tatars (24.2 percent) are the two other largest groups, followed by Mari, Chuvash, and Udmurt people.

The first autonomous republic of the Soviet Union, Bashkortostan issued a declaration of state sovereignty in October 1990, though soon went on to sign a federal power-sharing agreement with Moscow. Since Russian President Vladimir Putin took office in 2000, the region has been gradually stripped of nearly all its sovereign rights.

For several days in January, thousands of residents of Bashkortostan came together to protest the imprisonment of Bashkort activist Fayil Alsynov, one of the region’s most vocal advocates for Indigenous rights and a fierce critic of the extractivist colonial policies of the Kremlin and its local cronies.

Up to 5,000 people gathered outside a courthouse in the region’s southeastern town of Baymak on Jan. 15, the day of Alsynov’s expected sentencing on charges of “inciting interethnic hatred.” Likely startled by the size of the crowd outside, Judge Elina Tagirova then postponed the final hearing to Jan. 17.

On Jan. 17, a far larger crowd gathered at the scene again, defying an official warning from regional police, preemptive arrests of activists, and temperatures of minus 21 degrees Celsius in the frozen Urals. Some had made early morning journeys for several hours through snowy roads of southeastern Bashkortostan.

Alsynov’s main supporters are his fellow Bashkorts but others, including ethnic Russians and Volga Tatars, were among the protesters. So were men and women of all ages, white-collar workers, farmers, students, school teachers, opposition politicians, business owners, bloggers, veteran activists, and many others.

Though many of them hoped for a suspended sentence for Alsynov, the activist was eventually sentenced to four years in a penal colony. When the protesters refused to leave the scene following the verdict, riot police used smoke grenades, tear gas, and batons to disperse the crowd. As many as 40 people were forced to seek medical attention following clashes with the police.

Protests in Baymak and a subsequent smaller-scale solidarity rally in Bashkortostan’s capital Ufa have triggered an unprecedentedly large wave of regionwide arrests. The authorities have opened at least 163 administrative and 34 criminal cases against the protesters, according to independent monitor OVD-Info.

At least one of the people detained sustained life-threatening injuries in custody, and two men facing criminal investigation, 37-year-old Rifat Dautov and 65-year-old Minniyar Bayguskarov, died under unclear circumstances.

Russian commentators in both pro-Kremlin and anti-Putin liberal camps were quick to label the protests in Bashkortostan as “riots” with “ethnic nationalist” and “separatist” undertones that seemingly flared up out of the blue. Some even likened the events to the antisemitic riots that swept the capital of Russia’s North Caucasus republic of Dagestan last October.

But the recent protests—as I can say through my years of research there and intimate familiarity with the region’s politics—were neither of these things. Instead of being “nationalistic,” the protests ignited by Alsynov’s imprisonment were a manifestation of deeply rooted discontent with the ruthless exploitation of Bashkortostan’s resources by the Kremlin and its local cronies.

Bashkortostan undertook rapid Soviet industrialization amid the discovery of a vast number of natural resources—including petroleum, natural gas, coal, and limestone—coupled with the relocation of multiple industrial plants from Ukraine, Belarus, and western Russia during World War II.

The scope of environmental damage caused by decades of unchecked industrial development put environmental protection and Indigenous land rights at the forefront of the republic’s fight for independence in the 1990s.

As the republic lapsed from having a plethora of autonomous decision making powers to being fully subjected to the Kremlin’s control in just over three decades, environmental issues persisted along with new restrictions on usage of the Bashkort language and development of Indigenous cultures. This, in turn, expanded support for local environmental and Indigenous rights movements.

The symbiotic relationship between the two movements culminated in the 2020 protests in defense of Kushtau lime stone mountain, which saw Alsynov, a Bashkort rights defender with over a decade of experience, taking a leading role. The subsequent success of the protests brought Alsynov fame and admiration far beyond ethnic Bashkort circles.

Alsynov has played a critical role in the fight against illegal gold mining in Bashkortostan’s scenic and resource-rich Baymaksky district, which the authorities are trying to turn against him.

Bashkortostan’s pro-Kremlin authorities claimed that Alsynov “violated the human dignity” of migrant workers from the Caucasus and Central Asia by referring to them as qara halyq (“black people” in the Bashkort language) and that he called for expulsion of all non-Bashkorts from the republic in a speech made at the protests in April 2023.

Alsynov denied all charges against him, saying his speech was “gravely mistranslated” from his native Bashkort language by a government-affiliated linguistic expert. The activist also clarified that he “didn’t say that [non-Bashkorts] have no right to live or work” in the republic, but instead meant that Bashkorts have to fearlessly protect their native lands as they have no other place to live.

Qara halyq, the Bashkort phrase used by Alsynov, is not a racialized insult but, in fact, an idiom that exists across a number of Turkic languages and is used to refer to ordinary people.

No less absurd than accusations of “nationalism” are the attempts of some observers to present gatherings in Bashkortostan as “riots” instead of nonviolent protests.

From pro-sovereignty protests to standoff at Kushtau to last year’s anti-mining rallies, activists in Bashkortostan have been consistent in using nonviolent resistance methods and demonstrated dedication to maintaining nonviolent discipline in face of worsening repressions and authorities’ attempts to split the movement by offering concessions to its participants.

In building their nonviolent toolkit, Bashkort activists have relied on centuries-long practice of administering self-governance through yiyins, people’s gatherings aimed at resolving key political and social matters that can take place at a level of an individual clan, a village or even a nation.

Unlike traditional male-only yiyins, their modern form is more inclusive, with women now assuming active participation, although male elders and established community leaders still hold considerable influence over proceedings.

Activists in Bashkortostan also demonstrated their commitment to nonviolence during the Jan. 17 rally in Baymak. When agent provocateurs infiltrated the crowd and began throwing snowballs at the security service, protest leaders and experienced participants repeatedly encouraged those around to steer clear from engaging in physical confrontation and largely succeeded in maintaining discipline within the large crowd.

After witnessing the successes achieved by nonviolent movements worldwide and in its immediate surroundings, the Kremlin has been working overtime to suppress nonviolent dissent domestically.

In Bashkortostan, the team of the region’s head, Radiy Khabirov, has repeatedly tried to discredit the movement by portraying its participants as Islamist extremists seeking political destabilization and violent separation from Russia.

“Let’s save Bashkortostan from nazis, wahhabis and those sucking up to the oligarchs,” Khabirov’s infamous ex-PR chief, Rostislav Murzagulov, wrote of the 2020 protest in defense of Kushtau mountain.

A similar propaganda tactic has already been tried and tested by the Kremlin years before in Chechnya, when Moscow—with much success—used the narratives of the war on terror and ever-rising Islamophobic sentiments to justify military intervention into the region and disrepute the Chechen independence movement.

In Bashkortostan’s case, coupled with a lack of independent Indigenous media outlets and platforms willing to amplify voices of Indigenous activists on a countrywide level, this propaganda has proven widely effective.

Unfortunately for the movement’s participants and sympathizers worldwide, much of the analysis and coverage of recent protests in support of Alsynov, too, have been feeding into the government-sanctioned agenda. These reports, for example, made special note of the religious affiliation of protesters and stressed the fact that Bashkort, a movement that Alsynov was formerly part of, was designated “extremist organization” in 2020, while failing to mention that Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation was banned under the same pretext just a year later.

Persistently inaccurate and unflattering coverage of Bashkortostan’s nonviolent protest movement is, perhaps, one of the major reasons dissuading Western policymakers from treating it as a worthy partner.

Yet, as Indigenous activists double down on efforts to raise awareness about the events in Bashkortostan and support arrested activists and their families, the West has a unique chance to reimagine the course of Russia’s democratization and offer a helping hand to the regional movements that need it most.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 11.19 (after 1950)

1950 – US General Dwight D. Eisenhower becomes Supreme Commander of NATO-Europe.

1952 – Greek Field Marshal Alexander Papagos becomes the 152nd Prime Minister of Greece.

1954 – Télé Monte Carlo, Europe's oldest private television channel, is launched by Prince Rainier III.

1955 – National Review publishes its first issue.

1967 – The establishment of TVB, the first wireless commercial television station in Hong Kong.

1969 – Apollo program: Apollo 12 astronauts Pete Conrad and Alan Bean land at Oceanus Procellarum (the "Ocean of Storms") and become the third and fourth humans to walk on the Moon.

1969 – Association football player Pelé scores his 1,000th goal.

1977 – TAP Air Portugal Flight 425 crashes in the Madeira Islands, killing 131.

1979 – Iran hostage crisis: Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini orders the release of 13 female and black American hostages being held at the US Embassy in Tehran.

1984 – San Juanico disaster: A series of explosions at the Pemex petroleum storage facility at San Juan Ixhuatepec in Mexico City starts a major fire and kills about 500 people.

1985 – Cold War: In Geneva, U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Union General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev meet for the first time.

1985 – Pennzoil wins a US$10.53 billion judgment against Texaco, in the largest civil verdict in the history of the United States, stemming from Texaco executing a contract to buy Getty Oil after Pennzoil had entered into an unsigned, yet still binding, buyout contract with Getty.

1985 – Police in Baling, Malaysia, lay siege to houses occupied by an Islamic sect of about 400 people led by Ibrahim Mahmud.

1988 – Serbian communist representative and future Serbian and Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević publicly declares that Serbia is under attack from Albanian separatists in Kosovo as well as internal treachery within Yugoslavia and a foreign conspiracy to destroy Serbia and Yugoslavia.

1994 – In the United Kingdom, the first National Lottery draw is held. A £1 ticket gave a one-in-14-million chance of correctly guessing the winning six out of 49 numbers.

1996 – A Beechcraft 1900 and a Beechcraft King Air collide at Quincy Regional Airport in Quincy, Illinois, killing 14.

1998 – Clinton–Lewinsky scandal: The United States House of Representatives Judiciary Committee begins impeachment hearings against U.S. President Bill Clinton.

1999 – Shenzhou 1: The People's Republic of China launches its first Shenzhou spacecraft.

1999 – John Carpenter becomes the first person to win the top prize in the TV game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?.

2002 – The Greek oil tanker Prestige splits in half and sinks off the coast of Galicia, releasing over 76,000 m3 (20 million US gal) of oil in the largest environmental disaster in Spanish and Portuguese history.

2004 – The worst brawl in NBA history results in several players being suspended. Several players and fans are charged with assault and battery.

2010 – The first of four explosions takes place at the Pike River Mine in New Zealand. Twenty-nine people are killed in the nation's worst mining disaster since 1914.

2013 – A double suicide bombing at the Iranian embassy in Beirut kills 23 people and injures 160 others.

2022 – A gunman kills five and injures 17 at Club Q, a gay nightclub in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Neum: Međunarodni festival podvodnog filma/ Underwater Film Festival 2022

Svi koji vole more, rijeke, bazene, a pritom uživaju u podvodnom filmu i muzici su više nego dobrodošli. Anyone who loves sea, rivers, pools, and also enjoys underwater film and music, are more than welcome to join.

U sklopu manifestacije “Neumsko ljeto” u petak, 19. kolovoza, u 19.30 sati započinje Neum Underwater Film Festival 2022. koji će se održavati u hotelu “Zenit” u Neumu.

Prvu noć Neum Underwater Film Festivala biti će prikazano 27 filmova u službenoj konkurenciji, a ulaz na sve projekcije je slobodan.

“Zaključno s 15. kolovozom 2022. Organizacijski odbor zaprimio je enormno veći broj prijavljenih…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

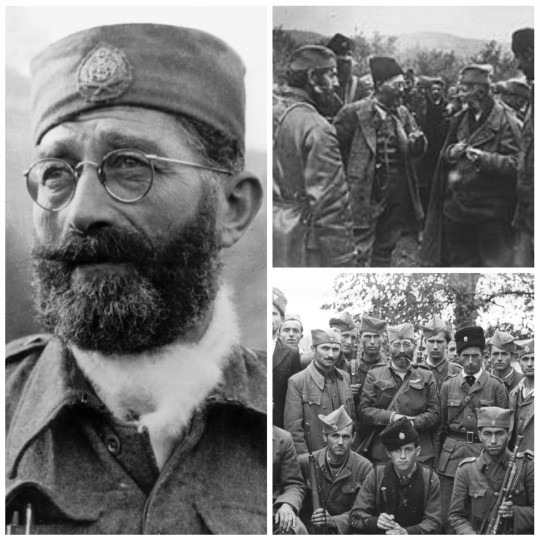

• Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović was a Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. A staunch royalist, he retreated to the mountains near Belgrade when the Germans overran Yugoslavia in April 1941 and there he organized bands of guerrillas known as the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army.

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović was born on April 27th, 1893 in Ivanjica, Kingdom of Serbia to Mihailo and Smiljana Mihailović. His father was a court clerk. Orphaned at seven years of age, Mihailović was raised by his paternal uncle in Belgrade. As both of his uncles were military officers, Mihailović himself joined the Serbian Military Academy in October 1910. He fought as a cadet in the Serbian Army during the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 and was awarded the Silver Medal of Valor at the end of the First Balkan War, in May 1913. At the end of the Second Balkan War, during which he mainly led operations along the Albanian border, he was given the rank of second lieutenant as the top soldier in his class, ranked sixth at the Serbian military academy. He served in World War I and was involved in the Serbian Army's retreat through Albania in 1915. He later received several decorations for his achievements on the Salonika Front. Following the war, he became a member of the Royal Guard of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes but had to leave his position in 1920 after taking part in a public argument between communist and nationalist sympathizers.

He was subsequently stationed to Skopje. In 1921, he was admitted to the Superior Military Academy of Belgrade. In 1923, having finished his studies, he was promoted as an assistant to the military staff, along with the fifteen other best alumni of his promotion. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1930. That same year, he spent three months in Paris, following classes at the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr. Some authors claim that he met and befriended Charles de Gaulle during his stay, although there is no known evidence of this. In 1935, he became a military attaché to the Kingdom of Bulgaria and was stationed to Sofia. On September 6th, 1935, he was promoted to the rank of colonel. Mihailović then came in contact with members of Zveno and considered taking part in a plot which aimed to provoke Boris III's abdication and the creation of an alliance between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, but, being untrained as a spy, he was soon identified by Bulgarian authorities and was asked to leave the country. He was then appointed as an attaché to Czechoslovakia in Prague.

His military career almost came to an abrupt end in 1939, when he submitted a report strongly criticizing the organization of the Royal Yugoslav Army. Among his most important proposals were abandoning the defence of the northern frontier to concentrate forces in the mountainous interior; re-organizing the armed forces into Serb, Croat, and Slovene units in order to better counter subversive activities; and using mobile Chetnik units along the borders. Milan Nedić, the Minister of the Army, was incensed by Mihailović's report and ordered that he be confined to barracks for 30 days. Afterwards, Mihailović became a professor at Belgrade's staff college. In the summer of 1940, he attended a function put on by the British military attaché for the Association of Yugoslav Reserve NCOs. The meeting was seen as highly anti-Nazi in tone, and the German ambassador protested Mihailović's presence. Nedić once more ordered him confined to barracks for 30 days as well as demoted and placed on the retired list. These last punishments were avoided only by Nedić's retirement in November. In the years preceding the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia, Mihailović was stationed in Celje, Drava Banovina (modern Slovenia). At the time of the invasion, Colonel Mihailović was an assistant to the chief-of-staff of the Yugoslav Second Army in northern Bosnia. He briefly served as the Second Army chief-of-staff prior to taking command of a "Rapid Unit" (brzi odred) shortly before the Yugoslav High Command capitulated to the Germans on April 17th, 1941.

Following the invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia by Germany, Italy, Hungary, a small group of officers and soldiers led by Mihailović escaped in the hope of finding Yugoslavian units still fighting in the mountains. After skirmishing with several Ustaše and Muslim bands and attempting to sabotage several objects, Mihailović and about 80 of his men crossed the Drina River into German-occupied Serbia. Mihailović planned to establish an underground intelligence movement and establish contact with the Allies, though it is unclear if he initially envisioned to start an actual armed resistance movement. For the time being, Mihailović established a small nucleus of officers with an armed guard, which he called the "Command of Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army". After arriving at Ravna Gora in early May 1941, he realized that his group of seven officers and twenty-four non-commissioned officers and soldiers was the only one. He began to draw up lists of conscripts and reservists for possible use. His men at Ravna Gora were joined by a group of civilians, mainly intellectuals from the Serbian Cultural Club, who took charge of the movement's propaganda sector. The Chetniks of Kosta Pećanac, which were already in existence before the invasion, did not share Mihailović's desire for resistance. In order to distinguish his Chetniks from other groups calling themselves Chetniks, Mihailović and his followers identified themselves as the "Ravna Gora movement". The stated goal of the Ravna Gora movement was the liberation of the country from the occupying armies of Germany, Italy and the Ustaše.

Mihailović spent most of 1941 consolidating scattered remnants and finding new recruits. In August, he set up a civilian advisory body, the Central National Committee, composed of Serb political leaders including some with strong nationalist views such as Dragiša Vasić and Stevan Moljević. Mihailović first established radio contact with the British in September 1941, when his radio operator raised a ship in the Mediterranean. On September 13th, Mihailović's first radio message to King Peter's government-in-exile announced that he was organizing Yugoslavia remnants to fight against the Axis powers. Mihailović also received help from officers in other areas of Yugoslavia, such as Slovene officer Rudolf Perinhek, who brought reports on the situation in Montenegro. Mihailović sent him back to Montenegro with written authorization to organize units there. Mihailović's strategy was to avoid direct conflict with the Axis forces, intending to rise up after Allied forces arrived in Yugoslavia. Mihailović's Chetniks had had defensive encounters with the Germans, but reprisals and the tales of the massacres in the Axis puppet state of Croatia made them reluctant to engage directly in armed struggle, except against the Ustaše in Serbian border areas. By the end of August, Mihailović's Chetniks and Josep "Tito" Broz's Partisans began attacking Axis forces, sometimes jointly despite their mutual diffidence, and captured numerous prisoners. On October 28th, 1941 Mihailović received an order from the Prime Minister of the Yugoslav Government in exile Dušan Simović who urged Mihailović to avoid premature actions and avoid German reprisals. Mihailović discouraged sabotage due to German reprisals (such as more than 3,000 killed in Kraljevo and Kragujevac) unless some great gain could be accomplished. Instead, he favoured sabotage that could not easily be traced back to the Chetniks. His reluctance to engage in more active resistance meant that most sabotage carried out in the early period of the war were due to efforts by the Partisans, and Mihailović lost several commanders and a number of followers who wished to fight the Germans to the Partisan movement.

Even though Mihailović initially asked for discreet support, propaganda from the British and from the Yugoslav government-in-exile quickly began to exalt his feats. The creation of a resistance movement in occupied Europe was received as a morale booster. Mihailović soon realized that his men did not have the means to protect Serbian civilians against German reprisals. The prospect of reprisals also fed Chetnik concerns regarding a possible takeover of Yugoslavia by the Partisans after the war, and they did not wish to engage in actions that might ultimately result in a post-war Serb minority. Mihailović's strategy was to bring together the various Serb bands and build an organization capable of seizing power after the Axis withdrew or were defeated, rather than engaging in direct confrontation with them. In contrast to the reluctance of Chetnik leaders to directly engage the Axis forces, the Partisans advocated open resistance, which appealed to those Chetniks desiring to fight the occupation. On September 19th, 1941, Tito met with Mihailović to negotiate an alliance between the Partisans and Chetniks, but they failed to reach an agreement as the disparity of the aims of their respective movements was great enough to preclude any real compromise. In mid-November, the Germans launched an offensive against the Partisans, Operation Western Morava, which bypassed Chetnik forces. Having been unable to quickly overcome the Chetniks, faced with reports that the British considered Mihailović as the leader of the resistance, and under pressure from the German offensive, Tito approached Mihailović with an offer to negotiate, which resulted in talks and later an armistice between the two groups on November 21st. Mihailović did not resume radio transmissions with the Allies before January 1942. In early 1942, the Yugoslav government-in-exile reorganized and appointed Slobodan Jovanović as prime minister, and the cabinet declared the strengthening of Mihailović's position as one of its primary goals. On January 11th, Mihailović was named "Minister of the Army, Navy and Air Forces" by the government-in-exile.

In Montenegro, Mihailović found a complex situation. The local Chetnik leaders, Bajo Stanišić and Pavle Đurišić, had reached arrangements with the Italians and were cooperating with them against the communist-led Partisans. Mihailović later claimed at his trial in 1946 that he was unaware of these arrangements prior to his arrival in Montenegro, and had to accept them once he arrived. Mihailović believed that Italian military intelligence was better informed than he was of the activities of his commanders. He tried to make the best of the situation and accepted the appointment of Blažo Đukanović as the figurehead commander of "nationalist forces" in Montenegro. While Mihailović approved the destruction of communist forces, he aimed to exploit the connections of Chetniks commanders with the Italians to get food, arms and ammunition in the expectation of an Allied landing in the Balkans. Having become more and more concerned with domestic enemies and concerned that he be in a position to control Yugoslavia after the Allies defeated the Axis, Mihailović concentrated from Montenegro on directing operations, in the various parts of Yugoslavia, mostly against Partisans, but also against the Ustaše and Dimitrije Ljotić's Serbian Volunteer Corps (SDK). During the autumn of 1942, Mihailović's Chetniks at the request of the British organization sabotaged several railway lines used to supply Axis forces in the Western Desert of northern Africa. Adolf Hitler wrote to Benito Mussolini on February 16th, 1943, demanding that in addition to the partisans be pursued the chetniks who possessed "a special danger in the long-term plans that Mihailovic's supporters were building." Hitler adds: "In any case, the liquidation of the Mihailovic movement will no longer be an easy task, given the forces at its disposal and the large number of armed Chetniks". From the beginning of 1943, General Mihailovic prepared his units for the supports of Allied landing on the Adriatic coast. General Mihailovic hoped that the Western Alliance would open the Second Front in the Balkans.

Mihailović had great difficulties controlling his local commanders, who often did not have radio contacts and relied on couriers to communicate. He was, however, apparently aware that many Chetnik groups were committing crimes against civilians and acts of ethnic cleansing; according to Pavlowitch, Đurišić proudly reported to Mihailović that he had destroyed Muslim villages, in retribution against acts committed by Muslim militias. While Mihailović apparently did not order such acts himself and disapproved of them, he also failed to take any action against them, being dependent on various armed groups whose policy he could neither denounce nor condone. Many terror acts were committed by Chetnik groups against their various enemies, real or perceived, reaching a peak between October 1942 and February 1943. Chetnik ideology encompassed the notion of Greater Serbia, to be achieved by forcing population shifts in order to create ethnically homogeneous areas. Chetniks forces engaged in numerous acts of violence including massacres and destruction of property, and used terror tactics to drive out non-Serb groups. Mihailović was certainly aware of both the ideological goal of cleansing and of the violent acts taken to accomplish that goal. In November 1942, Captain Hudson cabled to Cairo that the situation was problematic, that opportunities for large-scale sabotage were not exploited because of Mihailović's willingness to avoid reprisals and that, while waiting for an Allied landing and victory, the Chetnik leader might come to "any sound understanding with either Italians or Germans which he believed might serve his purposes without compromising him", in order to defeat the communists. A British senior officer, Colonel S. W. Bailey, was then sent to Mihailović and was parachuted into Montenegro on Christmas Day. His mission was to gather information and to see if Mihailović had carried out necessary sabotages against railroads. During the following months, the British concentrated on having Mihailović stop Chetnik collaboration with Axis forces and perform the expected actions against the occupiers, but they were not successful. In January 1943, the SOE reported to Churchill that Mihailović's subordinate commanders had made local arrangements with Italian authorities, although there was no evidence that Mihailović himself had ever dealt with the Germans. Bailey reported that Mihailović was increasingly dissatisfied with the insufficient help he was receiving from the British. Mihailović's movement had been so inflated by British propaganda that the liaison officers found the reality decidedly below expectations.

On February 28th, 1943, in Bailey's presence, Mihailović addressed his troops in Lipovo. Bailey reported that Mihailović had expressed his bitterness over "perfidious Albion" who expected the Serbs to fight to the last drop of blood without giving them any means to do so, had said that the Serbs were completely friendless, that the British were holding King Peter II and his government as virtual prisoners, and that he would keep accepting help from the Italians as long as it would give him the means to annihilate the Partisans. The British officially protested to the Yugoslav government-in-exile and demanded explanations regarding Mihailović's attitude and collaboration with the Italians. Mihailović answered to his government that he had had no meetings with Italian generals. Also in early 1943, the tone of the BBC broadcasts became more and more favourable to the Partisans, describing them as the only resistance movement in Yugoslavia, and occasionally attributing to them resistance acts actually undertaken by the Chetniks. During the Allied invasion of Italy the Italians heavily supported the Chetniks in the hope that they would deal a fatal blow to the Partisans. The Germans disapproved of this collaboration, about which Hitler personally wrote to Mussolini. At the end of February, shortly after his speech, Mihailović himself joined his troops in Herzegovina near the Neretva in order to try to salvage the situation. The Partisans nevertheless defeated the opposing Chetniks troops, who were in a state of disarray, and managed to go across the Neretva. In March, the Partisans negotiated a truce with Axis forces in order to gain some time and use it to defeat the Chetniks. While Ribbentrop and Hitler finally overruled the orders of their subordinates and forbade any such contacts, the Partisans benefited from this brief truce, during which Italian support for the Chetniks was suspended, and which allowed Tito's forces to deal a severe blow to Mihailović's troops. In late May, after regaining control of most of Montenegro, the Italians turned their efforts against the Chetniks, at least against Mihailović's forces, and put a reward of half-a-million lire for the capture of Mihailović, and one million for the capture of Tito.

In April and May 1943, the British sent a mission to the Partisans and strengthened their mission to the Chetniks. Mihailović returned to Serbia and his movement rapidly recovered its dominance in the region. Receiving more weapons from the British, he undertook a series of actions and sabotages, disarmed Serbian State Guard (SDS) detachments and skirmished with Bulgarian troops, though he generally avoided the Germans, considering that his troops were not yet strong enough. In Serbia, his organization controlled the mountains where Axis forces were absent. The United States sent liaison officers to join Bailey's mission with Mihailović, while also sending men to Tito. The Germans, in the meantime, became worried by the growing strength of the Partisans and made local arrangements with Chetnik groups, though not with Mihailović himself. From the beginning of 1943, British impatience with Mihailović grew. From the decrypts of German wireless messages, Churchill and his government concluded that the Chetniks' collaboration with the Italians went beyond what was acceptable and that the Partisans were doing the most severe damage to the Axis. By November and December 1943, the Germans had realized that Tito was their most dangerous opponent. At the end of October, the local signals decrypted in Cairo had disclosed that Mihailović had ordered all Chetnik units to co-operate with Germany against the Partisans. The British were more and more concerned about the fact that the Chetniks were more willing to fight Partisans than Axis troops. At the third Moscow Conference in October 1943, Anthony Eden expressed impatience about Mihailović's lack of action. The report of Fitzroy Maclean, liaison officer to the Partisans, convinced Churchill that Tito's forces were the most reliable resistance group. On December 10th, Churchill met King Peter II in London and told him that he possessed irrefutable proofs of Mihailović's collaboration with the enemy and that Mihailović should be eliminated from the Yugoslav cabinet. Also in early December, Mihailović was asked to undertake an important sabotage mission against railways, which was later interpreted as a "final opportunity" to redeem himself. However, possibly not realizing how Allied policy had evolved, he failed to give the go-ahead. This hastened the British's decision to withdraw their thirty liaison officers to Mihailović. The mission was effectively withdrawn in the spring of 1944.

At the end of August 1944, the Soviet Union's Red Army arrived on the eastern borders of Yugoslavia. In early September, it invaded Bulgaria and coerced it into turning against the Axis. Mihailović's Chetniks, meanwhile, were so badly armed to resist the Partisan incursions into Serbia that some of Mihailović's officers, including Nikola Kalabić, Neško Nedić and Dragoslav Račić, met German officers in August to arrange a meeting of Mihailović with Neubacher and to set forth the conditions for increased collaboration. From the existing accounts, they met in a dark room and Mihailović remained mostly silent, so much so that Nedić was not even sure afterwards that he had actually met the real Mihailović. According to British official Stephen Clissold, Mihailović was initially very reluctant to go to the meeting, but was finally convinced by Kalabić. It appears that Nedić offered to obtain arms from the Germans, and to place his Serbian State Guard under Mihailović's command, possibly as part of an attempt to switch sides as Germany was losing the war. Neubacher favoured the idea, but it was vetoed by Hitler, who saw this as an attempt to establish an "English fifth column" in Serbia. As the Red Army approached, Mihailović thought that the outcome of war would depend on Turkey entering the conflict, followed at last by an Allied incursion in the Balkans. He called upon all Yugoslavs to remain faithful to the King, and claimed that Peter had sent him a message telling him not to believe what he had heard on the radio about his dismissal. His troops started to break up outside Serbia in mid-August, as he tried to reach to Muslim and Croat leaders for a national uprising. Mihailović ordered a general mobilization on September 1st; his troops were engaged against the Germans and the Bulgarians, while also under attack by the Partisans. German sources confirm the loyalty of Mihailović and forces under his direct influence in this period. Mihailović's movement collapsed in Serbia under the attacks of Soviets, Partisans, Bulgarians and fighting with the retreating Germans. Still hoping for a landing by the Western Allies, he headed for Bosnia with his staff, McDowell and a force of a few hundred. He set up a few Muslim units and appointed Croat Major Matija Parac as the head of an as yet non-existent Croatian Chetnik army. Nedić himself had fled to Austria. On May 25th, 1945, he wrote to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, asserting that he had always been a secret ally of Mihailović. Now hoping for support from the United States, Mihailović met a small British mission between the Neretva river and Dubrovnik, but realized that it wasn't the signal of the hoped-for landing. McDowell was evacuated on 1 November and was instructed to offer Mihailović the opportunity to leave with him. Mihailović refused, as he wanted to remain until the expected change of Western Allied policy.

With their main forces in eastern Bosnia, the Chetniks under Mihailović's personal command in the late months of 1944 continued to collaborate with Germans. In January 1945, Mihailović tried to regroup his forces on the Ozren heights, planning Muslim, Croatian and Slovenian units. His troops were, however, decimated and worn out, some selling their weapons and ammunition, or pillaging the local population. In April, Mihailović set out for northern Bosnia, on a 280 km-long march back to Serbia, aiming to start over a resistance movement, this time against the communists. His units were decimated by clashes with the Ustaše and Partisans, as well as dissension and typhus. In May, they were attacked and defeated by Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), the successor to the Partisans, in battle of Zelengora. Mihailović managed to escape with 1,000–2,000 men, who gradually dispersed. Mihailović himself went into hiding in the mountains with a handful of men. The Yugoslav authorities wanted to catch Mihailović alive in order to stage a full-scale trial. He was finally caught on March 13th, 1946. The elaborate circumstances of his capture were kept secret for sixteen years. According to one version, Mihailović was approached by men who were supposedly British agents offering him help and an evacuation by aeroplane. After hesitating, he boarded the aeroplane, only to discover that it was a trap set up by the OZNA. The trial of Draža Mihailović opened on June 10th, 1946. His co-defendants were other prominent figures of the Chetnik movement as well as members of the Yugoslav government-in-exile, such as Slobodan Jovanović, who were tried in absentia, but also members of ZBOR and of the Nedić regime. Mihailović evaded several questions by accusing some of his subordinates of incompetence and disregard of his orders. The trial shows, according to Jozo Tomasevich, that he never had firm and full control over his local commanders. A Committee for the Fair Trial of General Mihailović was set up in the United States, but to no avail. Mihailović is quoted as saying, in his final statement, "I wanted much; I began much; but the gale of the world carried away me and my work."

Mihailović was convicted of high treason and war crimes, and was executed on July 17th, 1946 at the age of 53. He was executed together with nine other officers in Lisičiji Potok, about 200 meters from the former Royal Palace. His body was reportedly covered with lime and the position of his unmarked grave was kept secret. In March 2012, Vojislav Mihailović filed a request for his grandfather's rehabilitation in the high court. The announcement caused a negative reaction in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia alike. Former Croatian President Ivo Josipović stated that the attempted rehabilitation is harmful for Serbia and contrary to historical facts. He elaborated that Mihailović "is a war criminal and Chetnikism is a quisling criminal movement". The High Court rehabilitated Draža Mihailović on May 14th, 2015. This ruling reverses the judgment passed in 1946, sentencing Mihailović to death for collaboration with the occupying Nazi forces and stripping him of all his rights as a citizen. According to the ruling, the Communist regime staged a politically and ideologically motivated trial. The revised image of Mihailović is not shared in non-Serbian post-Yugoslav nations. In Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina analogies are drawn between war crimes committed during World War II and those of the Yugoslav Wars, and Mihailović is "seen as a war criminal responsible for ethnic cleansing and genocidal massacres." Monuments to Draža Mihailović exist on Ravna Gora (1992), Ivanjica, Lapovo, Subjel, Udrulje near Višegrad, Petrovo and within cemeteries in North America.

#second world war#world war ii#world war 2#military history#wwii#history#german history#yugoslav partisans#long post#Yugoslavia history#british history#partisans#biography

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consider climate impact on infrastructure suffering repeated flooding: experts

With key infrastructure in the Maritimes and Quebec again threatened by surging waterways, flooding experts say it's past time for fixes that consider worst-case climate change scenarios.

The New Brunswick government announced Wednesday night the closure of portions of the Trans-Canada Highway between Fredericton and Moncton -- for the second year in a row -- forcing detours for car traffic and thousands of trucks that use the trade corridor each day.

And on Thursday afternoon, Quebec officials issued an alert that a hydro dam on the Rouge River was at risk of failure, endangering about 250 people downstream. They ordered an immediate evacuation.

Surging rivers in the province have already been blamed for one death, damage to factories and homes and the closures of many secondary routes.

Slobodan Simonovic, director of engineering studies at the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction, says engineers and the scientific community need to move more swiftly to design infrastructure that accounts for climate change science.

"Go with the conservative prediction of the future. Go with something that is predicting high potential impact," said the civil engineer, who teaches at Western University in Ontario.

The federal climate change report released two weeks ago predicts extreme rainfall events, lasting over several days are expected to increase.

The report also notes that if current global carbon emissions continue, Atlantic Canada will experience a 12 per cent increase in annual precipitation over the next century, and a 30 per cent increase in one-in-10 year storms that produce large downpours of rain.

Blair Feltmate, head of the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation at the University of Waterloo, says efforts are underway at the National Research Council, the Standards Council of Canada, the Canadian Standards Association and his centre to develop fresh standards for infrastructure to adapt to climate change.

Solutions for roads already in place may include building protective berms, diversion channels to take storm waters from highways and holding ponds to keep water in safe locations, he said.

There may also be methods to place natural features near roads to absorb water before it spills onto the pavement, and management systems can be put into place to clear debris in culverts and prevent damming.

"We know what to do to take risk out of the system. The problem is complacency. We're simply not moving fast enough on these files," Feltmate said in an interview. "I think the light is starting to dawn. If we ignore it we do so at our own peril."

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made similar points on Wednesday, while visiting an evacuation centre in the city of Gatineau, Que., near where the Ottawa River jumped its banks.

"It means we have to think about adaptation, mitigation and how we are going to move forward together," he said.

Quebec is struggling with infrastructure problems of its own, as residents of several small islands in the Montreal area have been cut off from the world after officials were forced to close the only bridges linking them to the mainland.

Officials in Laval scrambled to set up dumpsters and emergency services for the 1,000 residents of the Iles-Laval on Thursday after the rising waters forced officials to close a bridge to vehicle traffic.

Across the province more than 2,500 homes were flooded and 2,184 were isolated -- their road or bridge access cut off by water. Some 919 people had been forced to evacuate.

One death has been blamed on the high water thus far, after 72-year-old Louise Seguin Lortie died last Saturday after driving her car into a sinkhole caused by flooding in the Pontiac area, about 30 kilometres northwest of Ottawa.

Kevin Manaugh, a geography professor and member of McGill University's School of Urban Planning, said it's not easy to protect transportation infrastructure in Quebec, where frigid winters, high precipitation and the freeze/thaw cycle form a "unique set of circumstances that makes it harder to plan for things that will last for decades and centuries."

He said that in urban areas especially, planners can turn to technical solutions such as using more permeable paving materials, planting trees and creating large water retention basins to help soak up the water near developed areas.

"The more we build green space and rainwater retention, these are solutions that exist to make sure the land can take more heavy rainfall," he said.

Civil engineer Guy Felio, senior adviser of asset management solutions at Stantec, said the key going forward is to build resilience in the roadways -- allowing them to adapt if rainfall predictions increase even further.

He says designers are now starting to consider the various climate change projections in their work to make highways more resilient.

That doesn't necessarily mean building roads higher and with harder materials -- at much higher costs, he said.

Rather, it may involve purchasing land alongside the highways to allow for holding ponds and other features to be added.

Paul Bradley, a spokesman for New Brunswick's Department of Transportation, said the flooding of the Trans-Canada Highway is the third such event since 2008 that has caused widespread damage.

"It's obvious our circumstances are changing and we need to change as well," he wrote in an email.

"Discussions about how we can reduce the impact of flooding on provincial infrastructure have already taken place."

Al Giberson, the general manager of the MRDC Operations Corp., the operator of the highway, said in a telephone interview that the road's condition will be assessed after the flood recedes.

"In the future, the assessments will have to include what the potential is for events like this ... and solutions will have to be developed for that. How long that takes, I can't answer right now," he said.

-- With files from Morgan Lowrie

from CTV News - Atlantic http://bit.ly/2ZDk8Mw

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The remarkable Mr Vokrri: Kosovo's football rise

New Post has been published on https://thebiafrastar.com/the-remarkable-mr-vokrri-kosovos-football-rise/

The remarkable Mr Vokrri: Kosovo's football rise

Fadil Vokrri (right) is considered the best footballer Kosovo has ever produced

All day the word “miracle” kept coming up. Maybe these thousands of people spilling out into Pristina’s streets have just seen another.

It was September 2016 when Kosovo played their first competitive international football match.

On Saturday, they extended an unbeaten run to 15 games with possibly their most significant result yet – a 2-1 home victory over the Czech Republic. It is the longest such run in Europe.

Kosovo already have a very good chance of reaching Euro 2020. And their next qualifier is against England on Tuesday (19:45 BST). They are relishing the prospect.

This country of about 1.8 million people campaigned for eight years before being admitted as Fifa and Uefa members in 2016. The process began immediately after its declaration of independence from Serbia in February 2008. Some countries – including Serbia – still do not recognise its right to exist.

That such a young and troubled nation from the heart of the Balkans should shine on football’s biggest stages was not the dream of only one man. But there is one figure who is revered here above all others – and his story helps explain the origins of this special team.

He was crucial to Kosovo’s campaign for recognition as a football nation, and is a hero in his country. After his death last year at the age of 57, the national team’s home ground was renamed in his honour: The Fadil Vokrri Stadium.

Like so many people here, Vokrri’s life was marked by the war that still raged in this region only just over 20 years ago. By the bitter cycle of vengeance and counter-vengeance, and the tensions between ethnic Albanians and Serbs that still exist today.

And yet Vokrri was one of very few – perhaps the only one – able to communicate across the deep divides that cost so many lives. Football was his language.

When Vokrri was made president of the Football Federation of Kosovo he was starting from scratch. His offices were two rooms in a Pristina apartment block; two desks and two computers. It was 16 February 2008. Kosovo declared its independence the next day.

Vokrri was in charge of an association with no money, he had a national team that didn’t have the right to play any official matches, in an isolated nation with little infrastructure.

What he did have was his reputation. He was the greatest footballer Kosovo produced – though that title may be challenged soon by the exciting new generation of talent that is emerging.

He was charming, charismatic and convincing. He and general secretary Errol Salihu were the campaigners the country needed.

“When we talked at home at this time, at the very beginning my father was thinking the process would be easy,” says Vokrri’s eldest son Gramoz, 33.

“Now we are recognised as a country, it will be fast, he thought. He soon realised it would be anything but easy, but he didn’t mind it that way.”

Gramoz lives in Pristina now. When he was old enough, he would often accompany his father and help with his work. Like his dad, he is well known in Kosovo’s capital. Conversation is interrupted every five minutes as allies and acquaintances stop to say hello. Many stay much longer. Among them are government officials, football agents, and former generals in the Kosovo Liberation Army.

“My father never made a political declaration in his life and only focused on football. Football is higher than everything else – that was his vision,” he says.

“It allowed my father to help achieve our goal – of entering Uefa and Fifa.”

Vokrri was an adventurous forward with two good feet. If he wasn’t the most prolific goalscorer perhaps his flair and determination made amends. He was loved by the fans. They recognised in him one of their own – even when he wasn’t.

Gramoz Vokrri with his father. This picture was taken around six months before Fadil Vokrri died in June 2018

He grew up in Podujeva, a small city which today lies close to Kosovo’s northern border with Serbia. Back then, just like the rest of Kosovo, it was part of Yugoslavia. He was born in 1960. During his childhood, Yugoslavia was a communist country made up of diverse nationalities, languages and religions, all more or less held together by its charismatic leader Josip Broz Tito.

It was an age when Kosovar Albanians like Vokrri were rarely celebrated. They seldom became symbols of Yugoslav pride. But this talent was impossible to ignore.

Vokrri was the first to play for Yugoslavia – and he would be the only one. His debut came in a 6-1 defeat by Scotland and scored the goal, the first of six in 12 caps between 1984 and 1987.

He had started out at Llapi, his hometown club, before moving to Pristina. In 1986 he went on to Partizan Belgrade and stayed for three years – “the most beautiful” of his career, he said.

They won the league title in 1987 and the cup in 1989. In between, Italian giants Juventus came calling – but Vokrri was forced to turn them down. He hadn’t completed the then-compulsory two years’ military service, and so couldn’t go abroad. He completed his duties while playing for Partizan, fulfilling light tasks during the week in between matches.

But leave the country he would, for reasons that were spiralling out of anyone’s control.

Kosovan boys play football at an Intercampus training session in a refugees’ camp in Albania during the Kosovo war, in June 1998

Many historians place President Tito’s death as the key point in the collapse of Yugoslavia. They say he left behind a power vacuum which would be filled by resurgent rival nationalist factions.

Born in 1986, Gramoz was the first of Vokrri and his wife Edita’s three children. By 1989, the family had decided they could stay in Yugoslavia no longer. Vokrri settled on the idea of leaving for France. In the summer, he signed for Nimes.

“At this time, everyone in Yugoslavia knew that war would happen,” Gramoz says. “They just didn’t know when or where it would start.”

Years of suffering would define the next decade. During the 1990s, Yugoslavia was plunged into a bloody conflict in which as many as 140,000 people were killed.

From this fighting emerged the separate modern territories of today: Serbia, Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and the recently renamed North Macedonia. Kosovo was the last to declare itself an independent nation.

A scene from life in Kosovo’s top flight in the mid-1990s as players wash after a match

Lulzim Berisha was 20 when he took up arms. He joined the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). It was 1998.

For the previous six years he had been in Pristina, still living under Yugoslav rule but playing football in what was an unofficial Kosovan top flight set up after the establishment of a separatist shadow republic there.

Matches were held on rough pitches in remote, rural locations. Fans would gather on sloping hillsides to watch. Serbian police would stop the players on the way and detain them for hours. But always somehow they managed to get word up the road for the opposition to wait. After the match, players would wash their muddy bodies in a nearby river.

This football league stopped when heavy fighting began in 1998.

“I decided to join the KLA because of my country,” says Berisha. “I had no military experience but I saw many bad things happening here. That was the reason.”

There was now open conflict between Kosovo’s independence fighters the KLA and Serbian police in the region. It led to a brutal crackdown. Civilians were driven from their homes. There were killings, atrocities and forced expulsions at the hands of Serb forces.

The key turning point in the war came in 1999. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) had already intervened in Bosnia and it did so again in Kosovo. A 78-day bombing campaign forced Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic to withdraw troops and allow international peacekeepers in. Milosevic’s government collapsed a year later. He would later be held at the United Nations (UN) war crimes tribunal for genocide and other war crimes carried out in Kosovo, Croatia and Bosnia. In 2006, he was found dead in his cell aged 64, before his trial could be completed.

After Serb forces left Kosovo in 1999, the territory remained under UN rule for nine years. About 850,000 people had fled the fighting. An estimated 13,500 people were killed or went missing, according to the Humanitarian Law Centre(HLC). The HLC, with offices in Pristina and Belgrade, continues to work on documenting the human cost of Yugoslavia’s wars – including the civilian victims of Nato’s bombardment.

As peace returned to the region, so did many of Kosovo’s refugees. Children were named after then UK prime minister Tony Blair – rendered in Albanian as one single first name: Tonibler. There is enormous gratitude in Kosovo to the countries that intervened. Nowhere is it more obvious than on Bill Clinton Boulevard in Pristina, where a giant image of the former US president looks out across the traffic below.

Now 41, Berisha uses few words to describe his life as a soldier and the violence he witnessed.

Lulzim Berisha at the Dardanet cafe and bar in Pristina

Today he is one of the main personalities behind the Kosovo national team’s biggest fan club: Dardanet. The name means “the Dardanians” – the people of an ancient kingdom that ruled here.

Dardanet have just opened a new cafe bar that serves as their headquarters. Opposite an old tile factory whose chimneys rise high into the sky, the call to prayer from a local mosque carries over lively conversation between the animated chain-smokers gesturing in their outside seats. The other fuels are dark black espresso coffee and conversation about football of any kind. Serie A is no longer the most passionately discussed. That would be the Premier League.

Lulzim sucks sharply on his teeth as a staccato point at the end of each short sentence.

“We want every kind of people to come to the stadium. Every game we give 100 tickets for free to female fans. We want families to come,” he says.

On the table next to us, a reel of tickets for the England match in Southampton is unfurled with glee. They arrived that morning. The visas to travel are through too. Lulzim explains there will be a match against an English fan club, England Fans FC, in Hounslow on Monday, before Tuesday’s Euro 2020 qualifier at St Mary’s.

Inside, the walls are packed high with framed photos of Kosovo players, new and old. Vokrri’s image is everywhere. They describe themselves as “Children of Vokrri”. He has become an icon for the fan club. They produce banners, T-shirts and online posts that carry his image under messages such as: “Looking down on us.”

“Vokrri is a legend,” says Berisha. “He is our hero. For everything he did. For the people.”

But pride of place in the fan club bar belongs to the match shirt worn by Valon Berisha when he scored Kosovo’s first goal in official competition. That was a 1-1 draw in Finland, a 2018 World Cup qualifier played in September 2016.

It was the culmination of many years’ hard work. Not so long afterwards, it looked like things would only go downhill.

Vokrri returned to Kosovo from France about five years after the war ended. With him at the helm, football’s world governing body Fifa turned down Kosovo’s first attempts towards membership in 2008. At that point the country had only been recognised by 51 of the UN’s 193 member nations. It seemed a majority would be required.

Instead, they continued to play unofficial matches against unrecognised states: Northern Cyprus, a team representing Monaco, a team representing the Sami people of north Norway, Sweden, Russia and Finland.

The players at this time were drawn almost exclusively from the domestic pool. People who had been forced to flee their homes only a few years ago, or who had taken up arms and fought.

There was another way. One that was still tantalisingly out of reach.

“In 2012, when Switzerland played a match against Albania, 15 of the players on the pitch were eligible to represent Kosovo,” Gramoz says.

“My father was at the game, watching with Sepp Blatter, then the Fifa president. Mr Blatter said to my dad: ‘How are you enjoying the match?’

“He replied: ‘It’s like watching Kosovo A versus Kosovo B.'”

The major step forward came in 2014, when Fifa allowed Kosovo to play friendly matches against its member nations – as long as certain conditions were met. There was still significant opposition from Serbia.

Mitrovica was the location for Kosovo’s first recognised friendly match. This city, with local Albanian and Serbian populations divided in two by the Ibar river, still requires the presence of Nato troops today, 20 years on from their arrival as a peacekeeping force. Oliver Ivanovic, a prominent politician seen as a moderate Kosovo Serb leader, was shot dead outside his party offices there in January 2018.

Albania goalkeeper Samir Ujkani chose to accept a call-up, as did Finland international Lum Rexhepi, Norway’s Ardian Gashi and Switzerland’s Albert Bunjaku. The opposition were Haiti. It finished 0-0.

“For us, it was a big, big victory,” says Gramoz.

“It was a clear message from Fifa. The moment they allowed us to play friendly matches we took that to mean: ‘Don’t stop, you will enter as full members – but we need time to prepare people.’

“Even if we didn’t have the right to play our national anthem, it’s OK. We play football. That was the most important thing.

“First of all friendly games. After that, our delegation was invited to a Uefa congress for the first time. My father went to the Ballon d’Or ceremony. We had indications that the work was going well.”

In May 2016, all the determined efforts, all the canvassing and campaigning done by Vokrri and Eroll Salihu finally came to fruition. Kosovo were admitted as full members, first of Uefa, then of Fifa.

“The whole country stopped. Everything,” says Gramoz. “After independence, it was the biggest thing that’s happened in Kosovo.

“People started throwing fireworks, pouring out into the streets. It was like we won the World Cup.”

At the Uefa vote, there were 28 in favour and 24 against, plus two invalid votes. Serbian Football Federation president Tomislav Karadzic said the result would “create tumult in the region and open a Pandora’s box throughout Europe”. It challenged the ruling at the Court of Arbitration for Sport. Uefa’s decision was upheld.

Now Kosovo had an official national team, it could take part in the upcoming qualifiers for the 2018 World Cup. But what would the team look like?

Kosovo delegation members react emotionally after receiving Uefa membership in May 2016

In June 2016, at the European Championship in France, Albania and Switzerland met again.

Among the Swiss side were Arsenal’s Granit Xhaka and Xherdan Shaqiri, now of Liverpool. Xhaka’s elder brother, Taulant, played for Albania. Each of these – and several more – might have decided to switch allegiances and join the new Kosovo team.

Uefa said it would consider applications to do so on a case-by-case basis. The Swiss FA released a statement complaining that Kosovo was unsettling its players. Gramoz believes Uefa’s strategy was a concession to those member nations worried about losing talent.

“Uefa and Fifa never said publicly that they all had the right to play – even though every application was successful,” he says. “It was very diplomatic.”

Xhaka and Shaqiri – perhaps the two best known eligible players – decided to stay with Switzerland. For those who did make the switch, the process did not go as smoothly as planned.

Five hours before kick-off in Kosovo’s first competitive match, the team was still awaiting clearance for six players – including one of their most promising, Valon Berisha, who had already played 19 times for Norway.

It was 5 September 2016. Eventually the clearance came through. Berisha played and scored the equaliser in a 1-1 draw in Turku on Finland’s west coast. It was an encouraging start, and a hugely emotional moment for players, fans and the country.

But Kosovo were beaten heavily in their next qualifier, 6-0 by Croatia – one of several home ties played in the Albanian city Shkoder. The national stadium in Pristina needed work to meet the required standards.

The draw in their first match against Finland would be their only point of the campaign. Kosovo finished bottom of their group, suffering nine consecutive defeats.

They had got a tough draw and, back then, perhaps it felt like just taking to the field was a victory.

Now the picture is very different indeed.

The day before Saturday’s game there is a thunderstorm in Pristina that flashes back against the black night sky, recalling a very different time from not so long ago. Peace lives here now. Even when the rain does fall it doesn’t bother the children chasing each other along the city’s central street, no matter the risk to their ice creams.

Down below, the stadium’s floodlights are lit. Kosovo are playing the Czech Republic the next day. Something very strange is about to happen.

The following morning, reports surface about arrests the police have made. Eight Czech fans were allegedly found with a drone, a Serbian flag and a banner reading “Kosovo is Serbia”. It seems a revenge stunt was planned.

In 2014, a drone flew over the Belgrade ground hosting a match between Serbia and Albania. It was carrying a banner labelling Kosovo part of “Greater Albania”. There was outrage. A mass brawl broke out on the pitch, fans streamed in from the stands and lashed out at players. The match was abandoned and Albania were eventually awarded a 3-0 default win.

Shortly after news of the arrests breaks, the Dardanet fan group responds. “We invite prudence and restraint,” they say. “Any potential incident could harm Kosovo.”

There is instead a happy ending.

Media playback is not supported on this device

Riot police had to be brought in to restore calm but the Serbia-Albania match was abandoned, as Wendy Urquhart reports

Going into the match, Kosovo are unbeaten in 14 games. Their last defeat was in October 2017. Six of those matches came in the inaugural Uefa Nations League, where performances have already guaranteed them a place in the play-offs for a spot at the Euro 2020 finals.

Georgia, North Macedonia and Belarus are the three other teams likely to contest Kosovo’s section of the play-offs. Only one of those countries recognises Kosovo – its southern neighbour North Macedonia.

Uefa currently keeps Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina apart from Kosovo for security reasons, but all other countries must play them. Uefa will allow a team to request their home fixture be played on neutral territory – as happened when Ukraine and Kosovo met in Poland in a World Cup qualifier in October 2016.

As for what happens should Kosovo reach Euro 2020, four of the 12 nations hosting games in next year’s tournament – Azerbaijan, Romania, Russia and Spain – do not recognize Kosovo’s independence either.

And it is beginning to look like they will make it. They might even end up qualifying automatically.

Come kick-off time, the Fadil Vokrri Stadium is packed. Tickets apparently sold out completely in 15 minutes.

Men in uniform are watching the sky through binoculars from the top of a high building opposite. There are no drones in sight. On the other side, a group of children have outdone them, perched atop an unfinished tower block that stands a good 10 storeys tall. The bent steel tips of its exposed reinforced concrete stretch higher above them still.

The Czechs take the lead. Arijanet Muric, the Nottingham Forest keeper on loan from Manchester City, is beaten by Patrick Schick’s delicate finish inside the box.

But the home fans rally their team. Their passion is raw and irresistible, and it runs through the Kosovo side and harries them forward. There are rash challenges, hurried touches at the vital moment. There is the bravery to persist, the drive to force their opponents back again and again.

Kosovo’s 68-year-old Swiss manager Bernard Challandes – appointed by Vokrri in March 2018 – is the only calm presence around. The whole ground is constantly carried away, including everybody who isn’t Czech in the press box.

Even when Vedat Muriqi gets the equaliser before half-time, Challandes keeps his cool. But when Mergim Vojvoda stabs the home team in front from a short corner there is a volcanic chain reaction of emotions: joy, pride, delight. Challandes cannot resist. The substitutes are up from the bench. The injured players who travelled to be with their team leap forward too – only a little more carefully.

With the final whistle approaching, the Czech Republic fashion four good chances in about three minutes. In extremely polite English totally at odds with the situation, the Kosovan journalist next to me says: “Phew, that was close.”

Five minutes of added time. Superstition kicks in. Fenerbahce striker Muriqi – a huge presence – hauls his team up the pitch, protecting possession like he has been for what seems an eternity. Challandes is gesturing wildly now, like everyone else.

And then the stadium erupts. The players hug each other. Challandes is under a mountain of tracksuited bodies. There is a long and reflective lap of victory. England are next. They cannot wait.

The Dardanet members wave their banners and sing their songs. The Children of Vokrri will go home very happy tonight – eventually.

When Vokrri died last June, having suffered a heart attack, his burial was marked by a special state ceremony in Pristina.

“Some Serbian officials came to his funeral, including the former FA president Tomislav Karadzic. It’s very rare to make a visit like that,” Gramoz says.

“Afterwards, Partizan Belgrade invited me to visit them. I went to Belgrade, and they showed me huge respect. They didn’t care if I was Albanian, they told me I was part of their family, because of my father.

“This is why I think, especially here in this case between Kosovo and Serbia, we should use sports and football to promote relations between the countries.

“It will be a great victory for our national team the day when a Kosovan Serb lines up with us on the pitch.”

Gramoz is perhaps like his father in that he likes to dream. But football can do powerful things. Here it has already done so much.

Kosovo fans celebrate their latest victory. The country has the youngest population in Europe with half its people under the age of 25

Media playback is not supported on this device

The conflict in Europe that won’t go away: Three BBC correspondents explain the Kosovo war two decades on

The ‘Heroinat’ (‘Heroines’) monument in Pristina honours the contribution and sacrifice of every ethnic Albanian woman during the 1998-1999 war in Kosovo

Ibrahim Rugova (left) became president of Kosovo’s separatist republic in 1992. Vokrri’s status as a footballer assisted him in his diplomatic efforts abroad – here the two are pictured in Turkey. Vokrri played for Fenerbahce from 1990-1992

Red Star Belgrade fans display a banner reading: ‘Kosovo is Serbia’ in a Uefa Cup match at home to Bolton in 2007

Fadil Vokrri and his wife and children lived in Montlucon in France during the Kosovo war. Vokrri was the coach of Montlucon FC. Gramoz says his father was constantly checking on family back home

Flamurtari FC’s football stadium in the Kosovo capital of Pristina. They finished sixth in the Kosovan top flight last season

Salihu (L) and Vokrri (R) waiting at the Uefa congress in Budapest in May 2016, when Kosovo was about to be made a member nation

Read More

0 notes

Text

Eurovision 2003 - Number 35 - Slobodan River - "What a Day"

youtube

Welcome to one Estonia's enduring Eurovision legends. Slobodan River is a certain Stig Rästa's first band. He's there, looking very young indeed. Together with another Eesti Laul Eurovision name, Tomi Rahula, producer of the entire competition from 2019 to 2023. Singing is Ithaka Maria aka Maria Rahula completing the band line-up.

For all of them, this is their first time preforming at Eurolaul, but Tomi and Maria have already had two songs competing as song-writers, and one of those songs was a certain Mere Lapsed sung by Koit Toome at Eurovision giving Estonia a 12th place finish in 1998

What a Day is a Baltic indie-pop banger plagued by so much dry ice you can barely make out the backing singers or the band through the mist. Lyrically, well, it's not so subtle. This appears to be a song about alfresco canoodling and woman who seduces the mind out of the subject of the song with her beach-based sexuality. It's... ...direct and to the point.

There are a lot of long-held notes in the chorus along with a heavy rhythmic pulse and a repeating, very standard four-bar chord progression. It's a song that has to move as fast a heart can pound while Maria cries over the top of it. Maria, her red hair and white outfit is not so much the focal point of the performance, as pretty much the only thing we get to see. She seems very pleased at the end of the song.

Maybe the lyrical content or the unrelenting central progression at the song's heart were what led to it only finishing joint 7th of the 10 songs competing at Eurolaul. Obviously this was not the end of the story for any of the band. All of them were back in 2004 as Slobodan River again, thereafter they entered again as individuals, members of new bands and even more often as song-writers. Stig made it to Eurovision stage in 2015, Tomi ran Eesti Laul through some of its more successful years and Maria went on to become Miss Estonia in 2018 at the age of 39 and as a mother of 3.

Before the split up in 2006, they did release one album, 2004's Surrounded featuring many of their best known songs including this one.

#Youtube#esc#esc 2003#eurovision#eurovision song contest#riga#riga 2003#national finals#Eurolaul 2003#Estonia#Slobodan River#Stig Rästa#Tomi Rahula#Ithaka Maria#miss estonia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

MITROVICA, Kosovo—A Kalashnikov fires through the darkness. It’s a short staccato burst upward, north of a bridge that separates two embittered communities living in a fragile peace, more than 22 years after a brutal civil war.

The conflict ended following an unprecedented NATO military air campaign, international sanctions, and the threat of a ground invasion—all to stop the genocidal actions of Serbian nationalist leader Slobodan Milosevic’s forces in Kosovo. By October 2000, in the face of growing opposition, Milosevic resigned from office. A brittle peace and nascent independent Kosovar state then took root in the Western Balkans.

Underlying issues, however, remain unresolved. Particularly in northern Kosovo’s city of Mitrovica, where a proud Serbian minority—surrounded by ethnic Kosovar Albanians—continues to maintain close ties to Belgrade and Moscow, occasionally participating in acts of violent defiance against the ethnic Albanian-led government in Pristina, Kosovo’s capital.

Mitrovica is a city divided. It is separated by the Ibar river. Serbs live north and Albanians south, while waning Bosniak and other minority communities remain stuck in the middle. It is an area rich in natural resources but torn across ethnic, religious, and political lines that prevent them from being exploited. Its demographics also make it ripe for a proxy battle between great powers.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine, things have gotten worse. Police actions from Kosovo’s special operations forces have increased, as have attacks on them—some involving hand grenades and automatic weapons. Politicians have used inflammatory rhetoric. And graffiti marks shabby streets with the symbol “Z” in support of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s so-called special military operation in Ukraine.

“Both sides are fucking us,” a local ethnic Serb police officer said, referring to Kosovo and Serbia, who in turn have allegiances to NATO and Moscow, during a visit to Mitrovica by Serbia’s prime minister, Ana Brnabic. As she left Belgrade, Brnabic’s convoy to Kosovo was joined by the Russian ambassador to Serbia, who was stopped at the border by Kosovo security forces and denied entry.