#Soudanese

Video

youtube

From a normal college student to a Supermodel|Anok Yai|#shorts #anokyai ...

#shorts#anokyai#supermodel#fame#viral#versace#fashion#runway#runwayshow#runwaymodeling#pfw 2024#top model#south soudanese model#modrels

0 notes

Text

Henry Jones Thaddeus - A Soudanese love song, Morocco (1889)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

(not) friendly reminder that Palestinian genocide started 60+ years BEFORE october 7th and is still a thing

(not) friendly reminder that the Soudanese civil war is ocurring while we speak

(not) friendly reminder that Congolese people are poisonned days after days in lithium mines to allow billionaire companies to produce more and more batteries and release useless technological innovations twice a year

(not) friendly reminder that Hawaï asks for independance and the regulation of tourism which destroy the island and increases poverty in the population

(not) friendly reminder that Russian army and government are still attacking Ukrainian people

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today, while walking to teach my lecture class, I had to take care of a Palestinian student who was loosing it in the corridor because the part of Rafah where her family had taken refuge was bombarded by Israel this very morning. She was being conforted by another Palestinian student who was loosing it a little less, because her family is in the West Bank currently. I made sure they were taken in by students services so they could at least be given a private place and more active mental health support than I could give in a corridor.

I'm not saying this to pat myself on the back. I'm saying this because it's been happening all over campus since October, but more in the last two weeks, and not only to a specific demographic of students. This has been happening all over campus to all kinds of students. Because of what's happening in Palestine, and Sudan, and Congo, and the US.

And if obviously right now it's Palestinian and Soudanese students who have it the hardest because of genocidal maniacs in positions of power (I've given trigger warning for colonial violence in my courses all semester because I've had students fall apart on me in class).

But, just before I made it to my office just now, I heard a very average white settler student state that she expects to die in a nuclear war before she has any children.

That's the world we live in folks.

It's a world where young people expect their world to end and others are seeing their world end, being ended.

Now in this hellsite, most of the people here are of that very generation, but there are enough geezers here who might not realize.

Us geezers? We are killing these kids. If we are not killing them literally, we are killing their spirit.

Do you know how many students commit suicide on campus in a average year? On every university campus for that matter? A lot. The number is two digits since September for my uni. How many more students will I have to walk to student services? How many of them will ask me, as the one today asked, if her family being bombed out of existence qualifies for getting Academic Accommodations?

I did not survive the Cold War and Reaganism for these kids to think the same thoughts as we geezers did.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gary K. Wolfe and Liz Bourke Review A Master of Djinn by P. Djèlí Clark

A Master of Djinn, P. Djèlí Clark (Tordotcom 978-1250267689, $ 27.99, 400pp, hc) May 2021. Cover by Stephan Martiniere.

The notion of magic returning to the world has been a familiar trope for so long that it’s nearly become part of the performance repertoire of fantasy writers, like locked-room murders for mystery writers or alien invasions for SF. The idea by itself doesn’t have much air left in it, so the way to make it work is to relegate it mostly to background, and to focus on the setting: the particular kinds of magic involved, and, more importantly, the kind of world that it engenders. P. Djèlí Clark seemed to have figured this out when he introduced us to his alternate 1912 Cairo in “A Dead Djinn in Cairo” in 2016, with its dandy-ish investigator Fatma el-Sha’arawi, her partly supernatural lover Siti, and an advanced, steampunkish Cairo featuring airships, clockwork trams, and automata (rather wonderfully called boilerplate eunuchs) – along with various troublemaking djinns, ghuls, sorcerers, and ifrits. The Ottomans and the British are long gone, and Cairo is one of the world’s great modern metropolises. In Clark’s followup, the Nebula-winning The Haunting of Tram Car 015, the main investigators – again working for the Ministry of Alchemy, Enchantments and Supernatural Entities – are Senior Agent Hamed al-Nasr and his new partner Agent Onsi, giving the tale a familiar veteran cop-and-sharp-newbie overtone. In this one we learn that Egypt is also well in advance of England in terms of women’s suffrage and social equity.

All these characters are back onstage in A Master of Djinn, Clark’s first full-length novel set in this colorful world, in which a Soudanese mystic named al-Jahiz had, 40 years earlier, somehow ruptured the membrane separating the world of djinn from our world, and then disappeared. Like the two earlier stories, it begins as a kind of procedural, as Fatma – now saddled with a junior partner she doesn’t want – investigates the gruesome mass murder of a group of mostly British wannabes calling themselves the Hermetic Brotherhood of Al-Jahiz and supposedly dedicated to “uncovering the wisdom” of the missing wizard. (The echo of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, another band of Brits out to co-opt esoteric teachings from other cultures, might be no accident.) The investigation quickly spirals outward, leading to a mysterious masked figure claiming to be the returned Al-Jahiz, whose nefarious plans threated to disrupt an upcoming World Peace Summit, which, it’s implied, might determine whether or not the First World War develops – although in many ways that’s the least apocalyptic outcome that Fatma must prevent.

Despite the wonderfully imagined progressive Cairo, Clark’s version of djinn-driven steampunk technology, and his ingeniously worked-out hierarchy of supernatural figures, the plot of A Master of Djinn draws on several familiar elements. Fatma makes a terrific heroine, but the new sidekick she resents, Hadia, turns out to be more competent than expected, like many such sidekicks, and while the local police inspector Aasim gets along with Fatma well enough, he sometimes echoes the officious and clueless cops of detective stories. Fatma’s mysterious, sexy, and kick-ass girlfriend Siti – easily the most appealing character in the novel – has secrets of her own, which expose her to some particular dangers. The antagonist shares not only the loopy megalomania of Bond villains, but the same habit of overexplaining the plan at critical junctures – the PowerPoint villain syndrome. And even though Clark plays pretty fair with the rules of a procedural, many readers won’t find it especially challenging to figure out the culprit’s true identity ahead of the detectives. That isn’t really a problem, though, since the novel leaves the procedural issues in the dust by its final third and amps up the spectacle to last-act MCU levels, bringing onstage ancient Egyptian deities, self-replicating ash-ghuls, fiery ifrit lords, giant flying rukhs, a fair amount of collateral civic demolition, and even Kaiser Wilhelm. It’s a huge amount of fun, and Clark handles it all with style, even as he leaves us with some intriguing unanswered questions about the relation of magic to snazzy clockwork technology, or the relation of both to improved human rights and enlightened governance. But then, who’s asking about governance with a giant flaming demon on your tail?

-Gary K. Wolfe

P. Djèlí Clark is writing some of the most interesting novellas and short stories around. A Master of Djinn, his first full-length novel, is set in the same continuity as award-nominated novella The Haunting of Tram Car 015 and the short story “A Dead Djinn in Cairo”, and it’s every bit as good as one might expect from the author of Ring Shout and The Black God’s Drums. A Master of Djinn‘s main character is Fatma el-Sha’arawi from “A Dead Djinn in Cairo”, a dapper, gender-non-comforming and over-achieving female agent from the Cairo office of Egypt’s Ministry of Alchemy, Enchantments, and Supernatural Entities – a good Muslim with a fondness for well-tailored European suits. And for her infidel lover, Siti, a worshipper of Egypt’s old gods.

For 40 years, ever since the mysterious inventor and mystic al-Jahiz poked a hole between worlds and let magic (and the djinn) back into our world, Egypt has led the way in magical and mystical developments, and in incorporating magic with technology. Al-Jahiz disappeared without a trace, but Egypt is now one of the world’s Great Powers, and Cairo is a lively modern city with plenty of problems for the Ministry to investigate.

A Master of Djinn opens with a gathering of an orientalist club – old white men with a fetish for antiquities – and their murder, by means including the magical, by a man-shaped figure all in black. The head of this club was Lord Worthington, whose murder, due to his wealth, is somewhat politically sensitive. He’s survived by two children, a son and a daughter. Fatma is called in to investigate because the kind of magic that kills a dozen people at once is bad news. And that’s before a black-clad person starts appearing in Cairo’s poorer neighbourhoods, claiming to be al-Jahiz returned and agitating against the government, spreading conspiracy theories along with rhetoric. And it seems this “al-Jahiz” can command djinn – though what he wants, beyond murder and unrest, remains uncertain. It will turn out that this mysterious figure wants nothing less than to overturn the whole magical order, and, you know, take over the world.

Meanwhile, Fatma – who’s run off every official partner she’s previously been assigned – has a new partner in the form of Hadia, one of the few other female agents in the Ministry and one who looks up to Fatma, an appreciation that Fatma does her best to stomp into pieces. And Fatma’s in a strange place with her lover Siti: Siti has secrets, is difficult to pin down, may or may not be interested in an actual long-term relationship, and is right in the middle of Fatma’s investigation, helpful and infuriating by turns.

The best way to describe A Master of Djinn is probably absolute gonzo pulp. Anti-colonial, anti-racist pulp (so very unlike old-style pulp), with a thoughtful heart and a deep appreciation for weird and bonkers world building elements. Clark evokes the messiness and complexity of (a version of) Cairo city, a society in constant flux, one that’s still grappling with what the last 40 years of progress mean. A Master of Djinn is one part mystery story, one part political thriller, and five parts action-adventure: Clark has a gift for compelling characters whose flaws as people make them all the more real, and all the more interesting. He has a gift, too, for deft and evocative turns of phrase, telling detail, and the kind of pacing that keeps you reading all in a rush, without ever feeling overly hectic or too fast to take everything in: I read A Master of Djinn in a single afternoon, and it broke a long spell where I had difficulty reading any fiction at all.

A Master of Djinn is doing a lot with class and status, history and myth, racism and race and (post)colonialism, with sex and gender and the pressures of being a first, exceptional role-model; with magic and relationships and community and policing. Mostly, though, it’s having fun. I’m not sure I’d call it a romp when the fate of the world’s at stake, but it’s definitely a rollicking great adventure. Entertaining, thoughtful, and deeply enjoyable, A Master of Djinn is an excellent novel. I recommend it highly.

-Liz Bourke

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I came across your post about the Sahel drought and it was really enlightening. Thank you for sharing! I would really like to know more about the colonial history behind it, do you know of any good books on the topic? I'll do my own research into the topic but I'm not really familiar with the region, so I'd really appreciate any recommendations you may have. I'll also look into articles but as those are less of a time sink, I figure I don't need to ask around about them. Thanks! :)

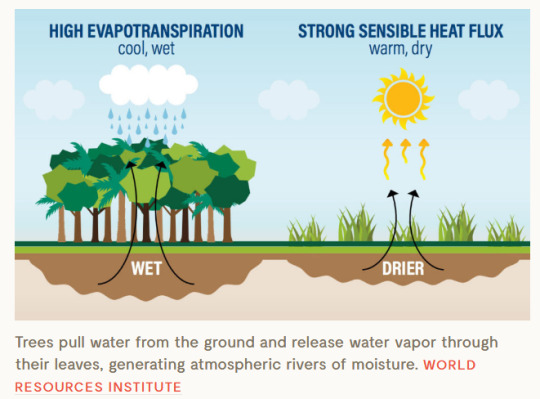

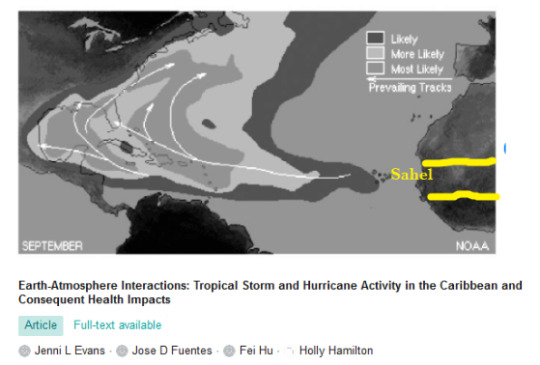

Thank you for your graciousness, the question, and the support. Though, I’m not a good person to ask. (Assuming we’re talking about this post where I claim that local-scale environmental degradation can have dramatic effects on global environmental trends in a short period of time, as in the case of colonial monoculture, deforestation, ungulate herd death, and precipitation in the Sahel, and its wider effects on Caribbean hurricanes, the mid-Atlantic, and global climate?) There is a whole genre of scholarly work about how NGOs, the W0rld B@nk, and I/M/F manipulate contemporary “peripheral places”, especially in Africa (following independence of the 1960s), and how these institutions carry out the work of dispossession, colonization, empire, extraction, etc. But I’m not too familiar with specific authors, scholars, books, etc. And a big disclaimer: I don’t like talking about more-technical environmental history outside of North American environments (or some parts of South America or Pacific Ocean littoral), because I don’t know much, so I don’t want to step too far out of my lane, and I’m only recommending some stuff because (1) of my interest in Holocene animal/plant distribution and extinction (including savanna/woodland/forest dieback and large mammals), and because (2) I’ve had mentors/acquaintances whomst worked with forests/horticulture in West Africa and the Sahel, and they’ve corroborated what the articles (listed below) suggest. In the past decade or two, since the advent of disk horse about “decolonization” and “multispecies justice,” it seems to me that academia is relatively more willing to explicitly identify extractivism/empire as a/the leading force in ecological degradation in a case like the Sahel. But still, to me, it also seems difficult to find scholarly/academic work about colonial and “post-independence” (read: neocolonial) environments in the Sahelian environment specifically because even when an author/academic is “liberal” or vaguely socialist-y or whatever, they still hesitate to fairly identify the colonial/imperial institutions which implemented the catastrophic environmental changes, and they also still frame events and narratives using terms like “underdevelopment” and “carbon sequestration” and “how can West Africans best exploit their environment for success/growth” (in other words, the writers are still focused on supporting extraction/development and “integrating” or “advancing” Africa by Euro-American standards, and are still engaging in a chauvinist or white-savior idea that the outsider/Euro-American “guidance” and “assistance” will “instruct” local communities how to “recover” from the era of more-overt colonization).

Just my opinion, though, from limited exposure. I am horrible with political theory. Anyway, here are some things that might be interesting?

Colonial/imperial/Euro-American role in drought, devegetation, soil death, and ungulate herd loss in the Sahel.

-- The Politics of Natural Disasters: The Case of the Sahel Drought. Edited by M.H. Glantz. 1976.

-- Melissa Leach and James Fairhead. Misreading the African Landscape: Society and Ecology in a Forest-Savanna Mosaic (1996) and Reframing Deforestation: Global Analysis and Local Realities: Studies in West Africa (1998).

-- The Lie of the Land: Challenging Received Wisdom on the African Environment. Edited by Melissa Leach and Robin Mearns. 1996.

-- Tor Benjaminsen and Pierre Hiernaux. “From Dessication to Global Climate Change: A History of the Desertification Narrative in the West African Sahel, 1900-2018.” Global Envionment Vol. 12 No. 4. 2019.

-- Kent Glenzer. “La Secheresse: The Social and Institutional Construction of a Development Problem in the Malian (Soudanese) Sahel, 1900-82.” Canadian Journal of African Studies. October 2013.

-- Hannah Holleman. Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of “Green” Capitalism. 2018.

-- David Anderson. “Depression, Dust Bowl, Demography, and Drought: The Colonial State and Soil Conservation in East Africa during the 1930s.” African Affairs. 1984.

Feedback loops of forest/woodland loss; and self-reinforcing forest dieback in the Sahel:

-- Patrick Gonzalez, Compton Tucker, and Hamady Sy. “A Climate Change Threshold for Forest Dieback in the African Sahel.” November 2006.

-- Fred Pearce. “Rivers in the Sky: How Deforestation is Affecting Global Water Cycles.” July 2018.

-- Peter Bunyard. “How the Biotic Pump Links the Hydrological Cycle and the Rainforest to Climate: Is it Real? How Can We Prove It?” Universidad Sergio Arboleda - Instituto de Estudios y Servicios Ambientales.

Sahel environment/climate affecting mid-Atlantic hurricanes and the Caribbean:

-- Mengqiu Wang et al. “The great Atlantic Sargassum belt.” Science. July 2019.

-- P.J. Lamb. “Large-scale tropical Atlantic surface circulation patterns associated with Subsaharan weather anomalies.” Tellus. 1978.

-- J.M. Prospero and P.J. Lamb. “African droughts and dust transport to the Caribbean: Climate change implications.” Science. 2003.

-- E.A. Shinn et al. “African dust and the demise of Caribbean coral reefs.” Geophysical Research Letters. 2000.

General cultural ecology and environmental history of the Sahel:

-- National Research Council. 1983. Environmental Change in the West African Sahel. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

-- National Research Council. 1983. Agroforestry in the West African Sahel. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

-- Jeffrey A. Gritzner. The West African Sahel - Human Agency and Environmental Change. 1989.

Another source that kinda incorporates many of these allegedly “disparate” aspects (colonization, climate, neocolonial lending institutions, devegetation, ungulate herd ecology, etc.):

A.R.E. Sinclair and J.M. Fryxell. “The Sahel of Africa: ecology of a disaster.” Canadian Journal of Zoology. May 1985.

Abstract: The Sahel is a fragile semiarid region extending through 10 countries south of the Sahara. Wild ungulate populations migrate to make use of nutritious but very seasonal food supplies. In doing this, they maintain a higher population size than they could as sedentary populations. Similarly, migratory pastoralists have traditionally lived with their cattle in balance with the vegetation. This balance was disrupted in the 1950's and 1960's by (i) the settlement of pastoralists around wells, and (ii) the expansion of agriculture north into the pastoralists' grazing lands. Land was lost both from overgrazing and from planting with cash crops coincident with increasing human and cattle populations. This has resulted in continuous famine in various parts of the Sahel since 1968. In addition, widespread soil denudation may be causing climatic changes towards aridity. [...] [Note that the 1950s/1960s settlement change coincides with “independence”.]

Some other stuff:

How devegetation in a seasonal woodland or subtropical/tropical forested area promotes self-reinforcing feedback loop of dieback (from Pearce, “Rivers in the Sky” 2018):

In another post I made about local Sahelian drought’s effects on global climate in far-away places:

The annoying graphic I made in that original post which illustrates the effect of this in the Sahel:

Which might promote hurricanes in the tropical mid-Atlantic:

And which might also promote things like “the largest seaweed bloom ever recorded”:

These noreasterlies, flowing over the Sahel, after traveling the tropical mid-Atlantic, also affect Amazonia:

“Forest species changes” and biodiversity loss in the Sahel, 1960 (independence era) to 2000. Graphic from Patrick Gonzalez, “A Climate Change Threshold ...” 2006:

--

Anyway, again, I’m not a good person to ask about this stuff. I hope some of these articles might be a good starting point to learn more, though.

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Every nation had all the races that fought in the war, except the United States”

“I saw the great victory parade, on July 14th, and I want to tell you— We need lessons, and had you been in the French crowd on July 14 for six hours, as I was, you too would say that we really need lessons. England, France, Belgium, the United States, Serbia, Greece, Italy, China, Japan, Portugal and one or two other nations had their representatives in line. England had Canadians, Australians, Scotch, Londoners, Indians and Africans in line. France had Frenchmen, Soudanese, Senegalese, Madagascans, Moroccans, and every other race that fought under her flag in line. Every nation had all the races that fought in the war, except the United States. Although there were over a thousand African American troops here outside of Paris, the United States was represented only by white men. The French people were very much amazed and put out, for they have not forgotten that three regiments of Black American soldiers were decorated for bravery by the French government. The French papers spoke of it, so I guess General Pershing felt as bad afterwards as I felt during the parade that they did not have at least one lot of fifty men with black faces in line under the stars and stripes.

Must the African American soldiers be ignored after the record made in this war? Their country called for men, and they responded. The color of their skin was not questioned when they were asked to give their lives for the United States. Why were they ignored in the Victory Parade in Paris, July 14, when all other races seem to have had their place?’

July 1919 Victory Parade, in Paris -- The Survey : social, charitable, civic : a journal ... v.42 (1919) – Photos: July 14th 1919 Victory Parade, Senegalese, Zouaves, saphis, and other colonials troops

Note: The U.S. Army banned black American troops from participating in the great victory parade staged by Allied soldiers in Paris on Bastille Day, 1919,

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lilliput and Blefuscu

These so-called Greek states, celebrated in the immortal pages of Thucydides, were but petty cock-pits wherein, like game birds, these historic republics crowed, strutted, and fought each other. Greek war, from the point of view of modern armies, was but the playing at soldiers like the people of Lilliput and Blefuscu. An army which could not defend such a country as Attica from invaders, or the army which having got beneath the Long-walls could not take Athens, can hardly be classed amongst soldiers at all. Scipio or Julius Caesar with one legion would have settled the Peloponnesian war in a few months.

As we behold it from a near height, we see that Athens always was, and always must be, an artificial city, resting entirely on its control of the’ sea and territory beyond sea. There is nothing behind Athens to support a population, and there never can be anything. Indeed in continental Greece itself, with its interminable barren rocks, there is no room for anything but a few herds, and sundry patches of olives, vines, currants, fruits, and tobacco. Continental Greece is in truth a mere mountain rising out of the sea, with a total population less than that of the city of Berlin.

Greece was therefore destined to be a sea power only, and, in recounting its achievements on land, her historians are liable to mislead us altogether. The Spartans no doubt remained for many centuries individually, like Soudanese, ‘first-class fighting men walking tours ephesus.’ But they knew nothing of scientific war, and seem throughout their history to have been commanded by mere drill-sergeants. They were, as a Frenchman irreverently remarked of another brave army, ‘lions led by asses.’ Their stupidity, slowness, incapacity to develop the art of war, their slavish adherence to routine and tradition, prevented them for ever being really effective; and, though they were a race of mere soldiers, they never became a really war-like race. The Athenians, however good at sea, were on land untrustworthy, excitable, undisciplined crowds of civilians.

They had hours of heroism

They had hours of heroism, as at Marathon; but, after all, Marathon was rather a moral victory, won by genius, dan, and a sort of spasmodic patriotism which astonished the victors as much as the defeated. It was hardly a great battle fought out on a regular plan. And, after Marathon, the Athenians did nothing very great on land. Their campaigns were unworthy of notice, and their conduct in the field has that character of unsteadiness which belongs to citizen levies. The Macedonians under Alexander were trained and excellent troops, equal perhaps to anything in ancient war; but the Macedonians were not Greeks. It is melancholy to think how largely the attention of academies and schools is absorbed in these trumpery scuffles which have no scientific interest of their own, and which, from the historical point of view, could have no serious result.

It is the wonderful literary and poetic genius of Greece which has given a halo to these petty manoeuvres. And to the same cause may be traced the singular phenomenon of the revival of Hellenism in the present century, by a people who, as a whole, have but a tincture of Hellenic blood. The process of reviving ancient Greece is still proceeding with immense rapidity, and in curious modes.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

Lilliput and Blefuscu

These so-called Greek states, celebrated in the immortal pages of Thucydides, were but petty cock-pits wherein, like game birds, these historic republics crowed, strutted, and fought each other. Greek war, from the point of view of modern armies, was but the playing at soldiers like the people of Lilliput and Blefuscu. An army which could not defend such a country as Attica from invaders, or the army which having got beneath the Long-walls could not take Athens, can hardly be classed amongst soldiers at all. Scipio or Julius Caesar with one legion would have settled the Peloponnesian war in a few months.

As we behold it from a near height, we see that Athens always was, and always must be, an artificial city, resting entirely on its control of the’ sea and territory beyond sea. There is nothing behind Athens to support a population, and there never can be anything. Indeed in continental Greece itself, with its interminable barren rocks, there is no room for anything but a few herds, and sundry patches of olives, vines, currants, fruits, and tobacco. Continental Greece is in truth a mere mountain rising out of the sea, with a total population less than that of the city of Berlin.

Greece was therefore destined to be a sea power only, and, in recounting its achievements on land, her historians are liable to mislead us altogether. The Spartans no doubt remained for many centuries individually, like Soudanese, ‘first-class fighting men walking tours ephesus.’ But they knew nothing of scientific war, and seem throughout their history to have been commanded by mere drill-sergeants. They were, as a Frenchman irreverently remarked of another brave army, ‘lions led by asses.’ Their stupidity, slowness, incapacity to develop the art of war, their slavish adherence to routine and tradition, prevented them for ever being really effective; and, though they were a race of mere soldiers, they never became a really war-like race. The Athenians, however good at sea, were on land untrustworthy, excitable, undisciplined crowds of civilians.

They had hours of heroism

They had hours of heroism, as at Marathon; but, after all, Marathon was rather a moral victory, won by genius, dan, and a sort of spasmodic patriotism which astonished the victors as much as the defeated. It was hardly a great battle fought out on a regular plan. And, after Marathon, the Athenians did nothing very great on land. Their campaigns were unworthy of notice, and their conduct in the field has that character of unsteadiness which belongs to citizen levies. The Macedonians under Alexander were trained and excellent troops, equal perhaps to anything in ancient war; but the Macedonians were not Greeks. It is melancholy to think how largely the attention of academies and schools is absorbed in these trumpery scuffles which have no scientific interest of their own, and which, from the historical point of view, could have no serious result.

It is the wonderful literary and poetic genius of Greece which has given a halo to these petty manoeuvres. And to the same cause may be traced the singular phenomenon of the revival of Hellenism in the present century, by a people who, as a whole, have but a tincture of Hellenic blood. The process of reviving ancient Greece is still proceeding with immense rapidity, and in curious modes.

0 notes

Photo

Lilliput and Blefuscu

These so-called Greek states, celebrated in the immortal pages of Thucydides, were but petty cock-pits wherein, like game birds, these historic republics crowed, strutted, and fought each other. Greek war, from the point of view of modern armies, was but the playing at soldiers like the people of Lilliput and Blefuscu. An army which could not defend such a country as Attica from invaders, or the army which having got beneath the Long-walls could not take Athens, can hardly be classed amongst soldiers at all. Scipio or Julius Caesar with one legion would have settled the Peloponnesian war in a few months.

As we behold it from a near height, we see that Athens always was, and always must be, an artificial city, resting entirely on its control of the’ sea and territory beyond sea. There is nothing behind Athens to support a population, and there never can be anything. Indeed in continental Greece itself, with its interminable barren rocks, there is no room for anything but a few herds, and sundry patches of olives, vines, currants, fruits, and tobacco. Continental Greece is in truth a mere mountain rising out of the sea, with a total population less than that of the city of Berlin.

Greece was therefore destined to be a sea power only, and, in recounting its achievements on land, her historians are liable to mislead us altogether. The Spartans no doubt remained for many centuries individually, like Soudanese, ‘first-class fighting men walking tours ephesus.’ But they knew nothing of scientific war, and seem throughout their history to have been commanded by mere drill-sergeants. They were, as a Frenchman irreverently remarked of another brave army, ‘lions led by asses.’ Their stupidity, slowness, incapacity to develop the art of war, their slavish adherence to routine and tradition, prevented them for ever being really effective; and, though they were a race of mere soldiers, they never became a really war-like race. The Athenians, however good at sea, were on land untrustworthy, excitable, undisciplined crowds of civilians.

They had hours of heroism

They had hours of heroism, as at Marathon; but, after all, Marathon was rather a moral victory, won by genius, dan, and a sort of spasmodic patriotism which astonished the victors as much as the defeated. It was hardly a great battle fought out on a regular plan. And, after Marathon, the Athenians did nothing very great on land. Their campaigns were unworthy of notice, and their conduct in the field has that character of unsteadiness which belongs to citizen levies. The Macedonians under Alexander were trained and excellent troops, equal perhaps to anything in ancient war; but the Macedonians were not Greeks. It is melancholy to think how largely the attention of academies and schools is absorbed in these trumpery scuffles which have no scientific interest of their own, and which, from the historical point of view, could have no serious result.

It is the wonderful literary and poetic genius of Greece which has given a halo to these petty manoeuvres. And to the same cause may be traced the singular phenomenon of the revival of Hellenism in the present century, by a people who, as a whole, have but a tincture of Hellenic blood. The process of reviving ancient Greece is still proceeding with immense rapidity, and in curious modes.

0 notes

Photo

Lilliput and Blefuscu

These so-called Greek states, celebrated in the immortal pages of Thucydides, were but petty cock-pits wherein, like game birds, these historic republics crowed, strutted, and fought each other. Greek war, from the point of view of modern armies, was but the playing at soldiers like the people of Lilliput and Blefuscu. An army which could not defend such a country as Attica from invaders, or the army which having got beneath the Long-walls could not take Athens, can hardly be classed amongst soldiers at all. Scipio or Julius Caesar with one legion would have settled the Peloponnesian war in a few months.

As we behold it from a near height, we see that Athens always was, and always must be, an artificial city, resting entirely on its control of the’ sea and territory beyond sea. There is nothing behind Athens to support a population, and there never can be anything. Indeed in continental Greece itself, with its interminable barren rocks, there is no room for anything but a few herds, and sundry patches of olives, vines, currants, fruits, and tobacco. Continental Greece is in truth a mere mountain rising out of the sea, with a total population less than that of the city of Berlin.

Greece was therefore destined to be a sea power only, and, in recounting its achievements on land, her historians are liable to mislead us altogether. The Spartans no doubt remained for many centuries individually, like Soudanese, ‘first-class fighting men walking tours ephesus.’ But they knew nothing of scientific war, and seem throughout their history to have been commanded by mere drill-sergeants. They were, as a Frenchman irreverently remarked of another brave army, ‘lions led by asses.’ Their stupidity, slowness, incapacity to develop the art of war, their slavish adherence to routine and tradition, prevented them for ever being really effective; and, though they were a race of mere soldiers, they never became a really war-like race. The Athenians, however good at sea, were on land untrustworthy, excitable, undisciplined crowds of civilians.

They had hours of heroism

They had hours of heroism, as at Marathon; but, after all, Marathon was rather a moral victory, won by genius, dan, and a sort of spasmodic patriotism which astonished the victors as much as the defeated. It was hardly a great battle fought out on a regular plan. And, after Marathon, the Athenians did nothing very great on land. Their campaigns were unworthy of notice, and their conduct in the field has that character of unsteadiness which belongs to citizen levies. The Macedonians under Alexander were trained and excellent troops, equal perhaps to anything in ancient war; but the Macedonians were not Greeks. It is melancholy to think how largely the attention of academies and schools is absorbed in these trumpery scuffles which have no scientific interest of their own, and which, from the historical point of view, could have no serious result.

It is the wonderful literary and poetic genius of Greece which has given a halo to these petty manoeuvres. And to the same cause may be traced the singular phenomenon of the revival of Hellenism in the present century, by a people who, as a whole, have but a tincture of Hellenic blood. The process of reviving ancient Greece is still proceeding with immense rapidity, and in curious modes.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

From Justinian to Isaac Comnenus

The fact is that, for the five centuries from Justinian to Isaac Comnenus, the attacks on the empire, from the European side, at any rate, were the attacks of nomad, unorganised, and uncivilised races on a civilised and highly- organised empire. And in spite of anarchy, corruption, and effeminacy at the Byzantine court, civilisation and wealth told in every contest. Greek fire, military science, enormous resources, and the prestige of empire always bore down wild valour and predatory enthusiasm. Just as Russia dominates the Turkoman tribes of Central Asia, as Turkey holds back the valiant Arabs of her eastern frontier, as Egyptian natives with British officers easily master the heroic Ghazis of the Soudan — so the Roman Empire on the Bosphorus beat back Huns, Avars, Persians, Slaves, Bulgarians, Patzinaks, and Russians. We need only to study the history of Russia and of Turkey to learn how the organising ability, the resources, and material arts of great empires outweigh folly, vice, and corruption in the palace.

4. Of course a succession of victorious campaigns implies a succession of valiant armies; and there is nothing on which we need more light than on the exact organisation and national constituents of those Roman armies which crushed Chosroes, Muaviah, Crumn, Samuel, and Hamdanids. They are called conventionally ‘Greeks’; but during the Heraclian, Isaurian ephesus daily tour, and Basilian dynasties there seem to have been no Greeks at all in the land forces. The armies were always composed of a strange collection of races, with different languages, arms, methods of fighting, and types of civilisation. They were often magnificent and courageous barbarians, conspicuous amongst whom were Scandinavians and English, and with them some of the most warlike braves of Asia and of Europe.

National characteristics

The empire made no attempt to destroy their national characteristics, to discourage their native language, religion, or habits. Each force was told off to the service which suited it best, and was trained in the use of its proper weapons. They remained distinct from each other, and wholly distinct from the civil population. But as they could not unite, they seldom became so great a danger to the empire as the Praetorian guard of the Roman army. The organisation and management of such a heterogeneous body of mercenary braves required extraordinary skill; but it was just this skill which the rulers of Byzantium possessed. The bond of the whole was the tradition of discipline and the consciousness of serving the Roman Emperor.

The modern history of Russia and still more the native armies of the British Empire will enable us to understand how the work ©f consolidation was effected. The Queen’s dominions are at this hour defended by men of almost every race, colour, language, religion, costume, and habits. And we may imagine the composite character of the Byzantine armies, if we reflect how distant wars are carried on in the name of Victoria by Hindoos, Musulmans, Pa- thans, Ghoorkas, Afghans, Egyptians, Soudanese, Zanzibaris, Negroes, Nubians, Zulus, Kaffirs, and West Indians, using their native languages, retaining their national habits, and, to a great extent, their native costume.

The Roman Empire was maintained from its centre on the Bosphorus, somewhat as the British Empire is maintained from its centre on the Thames, by wealth, maritime ascendency, the traditions of empire, and organising capacity — always with the great difference that there was no purely Roman nucleus as there is a purely British nucleus, and also that the soldiery of the Roman Empire had no common armament, and was not officered by men of the dominant race, but by capable leaders indifferently picked from any race, except the Latin or the Greek. Dominant race there was none; nation there was none. Roman meant subject of the Emperor; Emperor meant the chief in the vermilion buskins, installed in the Palace on the Bosphorus, and duly crowned by the Orthodox Patriarch in the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

0 notes

Photo

Lilliput and Blefuscu

These so-called Greek states, celebrated in the immortal pages of Thucydides, were but petty cock-pits wherein, like game birds, these historic republics crowed, strutted, and fought each other. Greek war, from the point of view of modern armies, was but the playing at soldiers like the people of Lilliput and Blefuscu. An army which could not defend such a country as Attica from invaders, or the army which having got beneath the Long-walls could not take Athens, can hardly be classed amongst soldiers at all. Scipio or Julius Caesar with one legion would have settled the Peloponnesian war in a few months.

As we behold it from a near height, we see that Athens always was, and always must be, an artificial city, resting entirely on its control of the’ sea and territory beyond sea. There is nothing behind Athens to support a population, and there never can be anything. Indeed in continental Greece itself, with its interminable barren rocks, there is no room for anything but a few herds, and sundry patches of olives, vines, currants, fruits, and tobacco. Continental Greece is in truth a mere mountain rising out of the sea, with a total population less than that of the city of Berlin.

Greece was therefore destined to be a sea power only, and, in recounting its achievements on land, her historians are liable to mislead us altogether. The Spartans no doubt remained for many centuries individually, like Soudanese, ‘first-class fighting men walking tours ephesus.’ But they knew nothing of scientific war, and seem throughout their history to have been commanded by mere drill-sergeants. They were, as a Frenchman irreverently remarked of another brave army, ‘lions led by asses.’ Their stupidity, slowness, incapacity to develop the art of war, their slavish adherence to routine and tradition, prevented them for ever being really effective; and, though they were a race of mere soldiers, they never became a really war-like race. The Athenians, however good at sea, were on land untrustworthy, excitable, undisciplined crowds of civilians.

They had hours of heroism

They had hours of heroism, as at Marathon; but, after all, Marathon was rather a moral victory, won by genius, dan, and a sort of spasmodic patriotism which astonished the victors as much as the defeated. It was hardly a great battle fought out on a regular plan. And, after Marathon, the Athenians did nothing very great on land. Their campaigns were unworthy of notice, and their conduct in the field has that character of unsteadiness which belongs to citizen levies. The Macedonians under Alexander were trained and excellent troops, equal perhaps to anything in ancient war; but the Macedonians were not Greeks. It is melancholy to think how largely the attention of academies and schools is absorbed in these trumpery scuffles which have no scientific interest of their own, and which, from the historical point of view, could have no serious result.

It is the wonderful literary and poetic genius of Greece which has given a halo to these petty manoeuvres. And to the same cause may be traced the singular phenomenon of the revival of Hellenism in the present century, by a people who, as a whole, have but a tincture of Hellenic blood. The process of reviving ancient Greece is still proceeding with immense rapidity, and in curious modes.

0 notes