#That revolves around some of the most brilliant philosophical themes

Text

Having two hardcore fandom obsessions on two WAY different ends of the spectrum at once is killing my brain, help

#On one end it's a huge massive puzzle that is probably made by the developer themselves to reveal something new about a game#That revolves around some of the most brilliant philosophical themes#And then there's the gay brainrot fanfic trope show that makes my shipping brain hop around like an excited birb#Where I've latched onto two extremely messed up characters who own my entire ass#hELP ME!!!!!!!!!!!#Yadda yadda

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

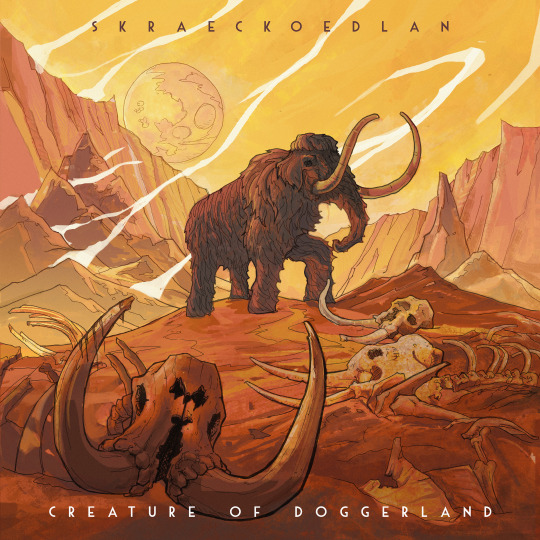

Swedish Sci-Fi Fuzz Freaks Skraeckoedlan Drop Third Single Ahead of ‘Earth’

~Doomed & Stoned Debuts~

Hot damn! This put me in a really good mood today. It's so good to hear new tunes from SKRAECKOEDLAN, the fuzz-drenched progressive stoner-doom outfit from Norrköping -- a city nestled in northeastern Sweden, about an hour-and-a-half's drive from Stockholm. Heavily rooted in the distinctives of their native soil, this three-piece sings entirely in Swedish, presenting a bit of a challenge to English-speakers, but no less an adventure in uncovering the backstory and interpretation of their songs...for nothing is at it seems.

A longtime favorite of Doomed & Stoned readers, the band has been wowing us with some of the most exciting songwriting on God's green earth since 2009. Now, a decade of dedication to anything is an accomplishment, but for a band with talents so laser-focused on their craft as Robert Lamu (guitar, vocals), Henrik Grüttner (guitars, vocals), and Martin Larsson (drums), it's a god damned milestone. The band, aptly named after an enormous prehistoric monster, has treated us to a pair of hefty long-plays already and now they brace for their third, 'Eorþe' (2019) on the esteemed Fuzzorama Records label.

The new record is a dense Lovecraftian tale by science fiction author Nils Håkansson, which he in fact wrote with the intention of having Skraeckoedlan bring to life over the course of these eight songs. It's a remarkable collaboration that is not only literary and musical, but visual, as well. The band worked once again with longtime artist Johan Leion to aid us in unlocking these mysteries of the faded past.

Today, Doomed & Stoned gives you a first listen to "Tentakler & Betar," which catches the narrative of Eorþe as it is nearing its end. The song is characterized by urgent beats, soaring vocal harmonies, weird effects, arpeggios that crawl like agitated spiders, and spirited riffs that fly and sing like the fowls of the air. Let me not fail to mention, too, that the sound is absolutely brilliant. The band tells us this about the number:

"This, the penultimate track of the album, takes us down into the darkness of the earth, as well as the mind. It explores what is left at journey's end and what to do when ambitions have been reached. Standing face to face with your obsessions, where do you go? As the cosmic clock relentlessly ticks, nothing will remain but tentacles and tusks."

February 15th is the date to watch for Skraeckoedlan's triumphant new album. It can be pre-ordered on some delicious looking vinyl variants here.

Give ear...

Some Buzz

Heavy riff power trio Skraeckoedlan are telling tales draped in metaphor. Fuzzy stories buried in melody are cloned into a one of a kind copy of an otherwise eradicated species. Previously found only in Sweden, this cold blooded lizard have once again started to walk the planet that we know as earth. The extinct is no longer a part of the past. Skraeckoedlan is the best living biological attraction, made so astounding that they capture the imagination of the entire planet.

The dinosaurs are believed to have made their first footprints on our earthen floor some 240 million years ago, during what is now known as the Triassic period. Indisputable behemoths and apex predators amongst them, they wandered freely and soared sovereign, ever evolving as the impending Jurassic and Cretaceous eras unfolded. Then, 65 million years ago, it stopped. Be it by asteroid or volcano, the dinosaurs’ fate became one shared with most species ever to inhabit our pale blue dot, extinction.

While Skraeckoedlan translates into something like dinosaur, an analogy better drawn is perhaps one to the great lizards’ descendants, the birds. In their flight there is a, quite literal, escapism to be found. A vital ingredient, encapsulating the bands very being. Although escape, it should be said, not necessarily in the sense of shying away but rather as a recipe for observation and introspection. A kind of fleeing of everyday worries in benefit of larger and hopefully more profound queries A bird’s-eye view, if you will.

"A prelude to the end. The moments of bliss before the imminent doom. We have journeyed to the place where it all unfolds, where the unseen rests and the secrets of the past lay buried. Here we too will become shrouded in mystery, riddles to be solved by those not yet granted a time and place in existence. Whatever the answers, one naked truth stands absolute. None shall leave the Ivory Halls."

Quite a few million years later than their reptilian namesakes, Skraeckoedlan is leaving their own footprints in earth’s soil, albeit not as physically grand. Their self-proclaimed fuzz-science fiction rock is an homage to the riff, vehemently echoing throughout the ages like that of a gargantuan Brachiosaurus striding freely. Equal in weight to the deafening heaviness of a Skraeckoedlan melody, these long-necked colossals further possess in their very defining feature the weapon needed for a complete experience of such melodies. Although strong neck or not, once in concert heads will, regardless of intent, be moving along.

Through their natively sung lyrics Skraeckoedlan invites us to partake in a world of cosmic awe inhabited by mythological beings and prehistoric beasts, like the immense havoc wreaking reptilian awakening from its slumber in the polar ice caps, featured on the debut full-length Äppelträdet (The Apple Tree), or the reclusive great ape Gigantos, solemnly wandering his mountain as one of several entities on the follow-up, Sagor (Tales). Against backdrops like these, underlying themes of the aforementioned big picture-nature are being explored, much in the spirit of, and hugely inspired by, great minds such as Alan Watts and Carl Sagan, fantastic creatures in their own respective rights.

"This song is, more than a part of the concept that is Eorþe, a story about life and the feelings of utter hopelessness our seeming oddity of an existence can often give rise to. It is a song about letting go and leaving behind. It’s about shattering the societal mirror and its reflection of illusionary demands and expectations, leaving your unhindered gaze looking ahead, to where your true calling lies. In short, it is a song about becoming truly free."

Formed in the city of Norrköping in 2009, Skraeckoedlan -- a reference to ‘Godzilla’ in Swedish -- are one of the most ambitious, original and multidimensional bands to emerge from Scandinavia in recent years.

Live shows with the likes of Orange Goblin, Kylesa, Greenleaf and other giants of the genre followed in the wake of Äppelträdet’s success and in 2015, with production underway on their follow-up album Sagor (Translated; ‘Tales’) Skraeckoedlan worked with a number of acclaimed producers including Niklas Berglöf (Ghost, Den Svenska Björnstammen) and Daniel Bergstrand (Meshuggah, In Flames, El Caco).

It wasn’t however until they met producer and technician Erik Berglund that they really found what was missing. Lifting the band to entirely new levels of musicianship, under his tutelage the creative process for Sagor not only left the band with an album they were immensely proud of, but one that sat deservedly at number two in the national Swedish vinyl sales chart in August of 2015.

"This song depicts the now submerged Doggerland as seen from the perspective of one of the mammoths who the continent used to house. In fact, we see through the eyes of Doggerland’s very last mammoth as its time amongst the living draws to a close. We occupy its head as thoughts of death and liberation mixes in a flurry of emotion and contemplation. Its destiny shared with the land upon which it walks, our traveler of tusk and wool journeys towards its final resting place while the North Sea rises ever higher, soon to swallow it all."

Like Galactus-in-reverse, their talent for constructing new worlds from the building blocks of heavy psychedelia and progressive rock is simply awe inspiring, and this February will see the release of their most accomplished vision yet: Eorþe (translated, "Earth").

In collaboration with sci-fi author Nils Håkansson who wrote the story behind the album specifically for Skraeckoedlan, Eorþe is set in the 1920s amid a mystery heavy with Lovecraftian influence and philosophical nuances. As the band explains, “This is by far our most ambitious work of art yet. It’s been a real challenge to do someone else’s story justice whilst making the songs cohesive as well as standing strong on their own. It took a lot of effort, but we’ve done just that.”

Having loyally served as heralds to Nordic folklore and science fiction since their inception, following the release of their early EPs in 2010 the band gained the kind of attention that could only lead on to the creation of a much-admired debut album in Äppelträdet (2011, translated; ‘The Apple Tree’) produced by Oskar Cedermalm from the legendary fuzz band Truckfighters.

Earth by Skraekoedlan

Heading into 2019 with the help of Fuzzorama Records, Skraeckoedlan steer a course to Eorþe, their first album in over three years and undoubtedly their most progressive. With the big metal riffs of ‘Kung Mammut’ riding shotgun alongside the more introspective and explorative moments of songs like ‘Mammutkungens Barn’ and ‘Angra Mainyu’, the trio have cut a definitive and spellbinding record of light and dark.

In addition to the CD and standard vinyl editions, Eorþe will also come in a limited-edition box set which sees the album split across two gatefold vinyl records: Earth: Above and Earth: Below. The set will come packed with pieces of merchandise that revolve around the story and feature alternative artwork.

Follow The Band

Get Their Music

#D&S Debuts#Skraeckoedlan#Norrköping#Sweden#Doom#Metal#Progressive Rock#Stoner Rock#Fuzz#Fuzzorama Records#HeavyBest19#Doomed & Stoned

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

One of the most iconic filmmakers of all time, Andrei Tarkovsky was known for his philosophical themes and lazily-paced long takes, among other memorable tropes. All through his career, the Russian auteur had experimented with several genres, ranging from sci-fi (Stalker, Solaris) to war drama (Ivan's Childhood).

RELATED: Andrey Zvyagintsev & 9 Other Modern Russian Directors Every Movie Fan Should Check Out

His approach towards filmmaking lay heavy emphasis on 'sculpting in time' as Tarkovsky believed that a major motive of cinema is to alter the notions of time. With minimal cuts and long takes, his films succeeded at not looking like different shots arranged in one sequence. Rather, his narratives convey the idea of the passage of time in a seemingly realistic rhythm.

10 There Will Be No Leave Today (1959) - 6.5

Back in the late 1950s, film students Aleksandr Gordon and Andrei Tarkovsky directed this 47-minute-long war drama that recounted an actual incident from Russian history. There Will Be No Leave Today is set in a small Russian town that faces the threat of unexploded bombs from the Second World War. Hence, an army unit is tasked with evacuating the town and safely detonating these bombs.

After being broadcast on Soviet TV in 1959, the student film was then recovered in the 1990s. It offers an early glimpse at Tarkovsky's budding talent at showcasing human emotions and building atmospheric tension.

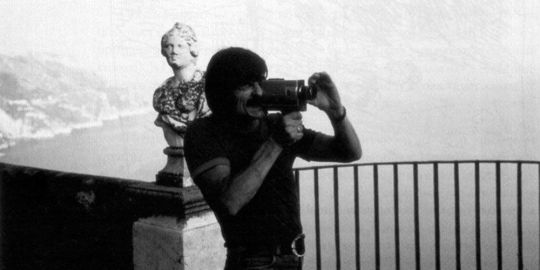

9 Voyage In Time (1983) - 7.3

The only documentary directed by Tarkovsky, Voyage in Time focused on his travels in Italy with screenwriter/co-director Tonino Guerra as they prepared to shoot the former's drama feature Nostalghia.

Voyage In Time serves as an interesting peek into Tarkovsky's psyche as a filmmaker and as a person as he and Guerra delve into philosophical matters among their usual conversations on cinema. Further, the director also touches upon his other influences that include Federico Fellini, Jean Vigo, and several others.

8 The Steamroller And The Violin (1961) - 7.4

The Steamroller And The Violin was Tarkovsky's third diploma film during his student days at State Institute of Cinematography, Moscow. It happens to one of his most emotion-driven films as it explores the friendship between a young violinist (Igor Fomchenko) and an aging steamroller operator (Vladimir Zamansky).

RELATED: 10 Soviet Classic Films That Made An Impact On World Cinema

Facing a general sense of isolation from society, both friends spend their evenings talking to each other about their day-to-day activities. While the boy usually plays his violin, the old man delves into his past telling his friend stories from the War.

7 Mirror (1975) - 8.1

For some cinephiles, Mirror would possibly be Tarkovsky's most enigmatic film largely due to its free-flowing non-linear structure and a sense of storytelling that would resemble the 'stream of consciousness' style of writing (popularized by James Joyce and Virginia Woolf).

In its essence, the film recalls a dying poet's final days as he remembers his life and remnants of Soviet history and society. There's a lot to interpret in Mirror easily making it a film worth multiple viewings. While Tarkovsky authored the screenplay, the film heavily incorporates poems written and recited by his father Arseny Tarkovsky.

6 Solaris (1972) - 8.1

Solaris, along with classics like 2001: A Space Odyssey, can largely be credited in ushering in an age of introspective, thoughtful space sci-fi that focused on human themes rather than just a fascination for the extraterrestrial. Solaris revolves around a space station inhabited by a crew displaying bizarre emotional traits, that are further analyzed by psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis) when he arrives at the station.

RELATED: 10 Sci-Fi Movies That Only Make Sense On A Rewatch

Solaris won the Grand Prix at Cannes and established Tarkovsky as a visionary in sci-fi cinema. Many of his ideas would be further explored in Stalker.

5 Stalker (1979) - 8.1

Just like Solaris, Stalker is a sci-fi tale rooted in philosophical questions. Even though it drew mixed reviews initially, it is yet again regarded as one of the finest sci-fi films today.

Alexander Kaidanovsky plays the ominous 'Stalker,' a man entrusted with transporting people to the 'Zone.' This so-called 'Zone' is a region where anyone's innermost desires can be fulfilled. Despite its thoughtful musings, the film also brims with a thriller-like aura that would keep audiences guessing about the actual nature of the grim, distant future of Stalker.

4 Andrei Rublev (1966) - 8.1

Even though Andrei Rublev is set in medieval Russia, its dominant theme of artistic freedom is very much relevant in present times. The titular personality (Anatoly Solonitsyn) is an iconographer who opposes an oppressive regime while pursuing his art. For its direct jabs at authoritarian states all over the world, Andrei Rublev either faced censorship or a total ban in its initial run.

RELATED: 10 Best Movies About Famous Artists, According To IMDb

Apart from serving as a fictionalized biopic of its protagonist, Tarkovsky's sophomore feature film was a bold case study of Russian society in the fifteenth century, an era characterized by religious power struggles and the eventual transition to Tsardom.

3 The Sacrifice (1986) - 8.1

Offret aka The Sacrifice was Tarkovsky's final directorial effort before he succumbed to terminal lung cancer. The film can be described as magical realism at its finest as it centers around a heavily nuanced take on humanity and religion. In order to stop an impending nuclear holocaust, an intellectual attempts to negotiate with God, a deal that would require a 'sacrifice.'

Opening to rave reviews, the Swedish-language film earned Tarkovsky his second Grand Prix at Cannes along with a BAFTA for Best Film Not In The English Language.

2 Nostalghia (1982) - 8.1

Nostalghia (alternatively released as Nostalgia) was Tarkovsky's first film shot outside the Soviet Union, incorporating some of his own notions of homesickness. It stars Oleg Yankovsky as a writer studying the life of a Russian composer who spent his final days in Italy. While exploring the Italian countryside, he himself goes through bouts of isolation and displacement.

The autobiographical nature in Nostalghia is clear to see with the narrative further adorned with memorable Tarkovsky elements like dream sequences and a hopeless protagonist.

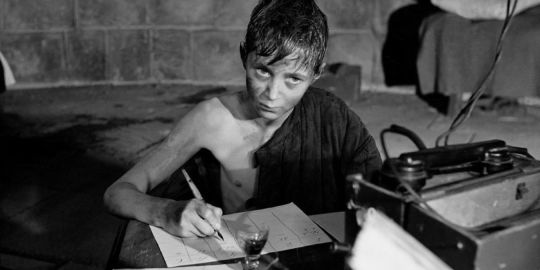

1 Ivan's Childhood (1962) - 8.1

Barring his student films, Ivan's Childhood marked Andrei Tarkovsky's full-fledged directorial debut, going down in cinematic history as one of the best first films ever.

The movie endures as a brilliant example of expressing the human cost of war as it studies wartime trauma from the eyes of an orphaned boy Ivan (Nikolai Burlyayev). Losing his parents to German forces, Ivan struggles to survive as the Second World War rages on affecting both sides of the conflict. A hard-hitting feature, it boldly proclaimed its director's anti-war sentiments.

NEXT: The 10 Best World War II Epics, Ranked

Top 10 Andrei Tarkovsky Movies, According To IMDb | ScreenRant from https://ift.tt/3fSdXNo

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sundance 2019: The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Clemency

Joe Talbot’s “The Last Black Man in San Francisco” is the tale of two friends, Jimmie (Jimmie Fails) and Montgomery (Jonathan Majors), and a Victorian home in the middle of a highly gentrified neighborhood. Jimmie claims that his grandfather built every part of the home back in the 1940s, and he just wants it back in the family. The house, which he goes so far as to paint when its current owner is not home, is more than just a building to him. It’s a heartbreaking symbol for how the whole city he grew up in has changed, and has devalued the lives of men and women like him. But this emotional set-up for the script, co-written by Fails and Talbot, is only just the foundation for what proves to be a singular, luminous American story.

“The Last Black Man in San Francisco” proclaims a next-level brilliance from it opening sequence in which Jimmie and Montgomery speed around San Francisco (Jimmie on his skateboard, Montgomrey sometimes dashing behind him), displaying Talbot's major league precision in color, editing, motion, and music. It gets a true adrenaline from this filmmaking in its first half, going from one visually stunning scene from the next, introducing a wildly new color palette compared to the last. This is the kind of movie that sucks you in with its vision, that begs to be rewatched in order to savor every shot or strange little item in its production design for various living spaces (like the cluttered home of Danny Glover’s supporting character and grandfather to Montgomery). Talbot quickly announces himself as a filmmaker who actively considers everything going on in a frame, and how to define his characters by their surroundings, and the music that accompanies them (a whimsical Joni Mitchell song over the aggressive Greek chorus of men that talk shit outside Grandpa Allen's house is probably the best example). All the while, different tones of storytelling are blended—some beats are extremely funny in their dry manner, others are completely heartbreaking—and “The Last Black Man in San Francisco” remains consistently gorgeous and unpredictable.

Talbot doesn’t lean on this energy the entire time: the second half is more subdued, spending more time in the house, while getting to know the men internally. It’s a crucial choice, as the film would've been exhausting if it went the same speed from start to finish, and it helps the movie go inward, detailing the lives of supporting people like Kofi, a member of that Greek chorus who talks shit about Montgomery and Jimmie being "soft." In more tender moments, Talbot's film observes how these men have a friendship that itself is like a peaceful family, a contrast to the lost relationships they have with their own parents.

A pivotal aspect to this story are Jimmie and Montgomery. They’re two gentle friends who are clearly removed from the aggression that's observed in other black men within this film. They reminded me most of Charlie Brown and Linus from Charles Schultz’s “Peanuts” comics: Along with both of them wearing the same clothes in every day, Majors clings his red drawing book like Linus does with his blanket, while being the introspective, philosophical one. They both have a boyish innocence that is striking, a very specific artistic choice in their acting and in storytelling that works as an honest expression on the film’s contrasting portrayals of masculinity.

Talbot displays perhaps his most confidence with his script (co-written by Talbot and Fails), which is simplified to the two men trying to get the house, fill it with themselves, and hold onto it. He wants you to appreciate the magic of the house, the way that light cuts through in different rooms, its ornate detail from start to finish. Even more, he wants you to recognize and love these characters, too. The film's incredible tension comes from watching Jimmie and Montgomery in this gorgeous city--alongside other larger-than-life individuals--and seeing just how much these men do not have a place in it.

“Clemency” is one of the toughest films playing in the Sundance’s U.S. Dramatic Competition this year, but with its tactful and rich world-building for its story about the death penalty, it’s also one of the best. Writer/director Chinonye Chukwu uses calibrated artistry across the board to tell a sensitive story about a prison warden’s very challenging position of power, its performances providing unforgettable faces for those whose lives circle around capital punishment.

In a stunning opening scene, we see a lethal injection go wrong, requiring different needle placements and horror for those who have been selected to watch. It is not a peaceful route to the required result. All the while, Alfre Woodard’s Warden Bernadine Williams remains impossibly stoic as she stands over the man. It’s just one moment in which you see the control that she has over this place, a woman caught between a clear pride she has for her work that has elements that continue to wear down on her. Throughout the film, Woodard is brilliant in how she shows a woman who does not easily let her guard down in a job that demands so much of her strong spirit, something that affects her relationship with her husband Jonathan (Wendell Pierce) and can be challenged whenever she interacts with the prisoners that she knows more like a caring teacher than someone just working a job. When Bernadine does reach her breaking point, after later seeing the tragedy of her work, it’s a masterful display of a face failing to beat its repressed emotions, and Chukwu holds on her face for a stunning minute-long close-up.

But more than just about Warden Williams and the prison she watches over, the story is about a life we see in the headlines: Aldis Hodge’s Anthony Woods, a man sentenced to death for the killing of a cop, which he insists he didn’t do. Hodge carries on the film’s exhilarating ambition to express feelings that are unconscionable outside of a prison cell, like when he silently processes that he is finally about to die after a visit from Woodard’s character and then aims to smash his head against a concrete wall. Later, he helps “Clemency” show the tragedy of men like Anthony, as he gets a glimmer of hope that he might belong to a family, and clings to that fantasy while waiting on a message of clemency from the governor. One of the best supporting turns at Sundance this year, it's an incredible physical and emotional feat.

Within Chukwu’s impressive work with this material, she populates the story with concrete themes as explored by side characters who revolve around Warden Williams, and fill in the world of “Clemency.” Wendell helps paint a sense of the sometimes silly, but conflicted home that Warden Williams can return to, and has a striking moment in which he quotes Invisible Man to his high school students, while Chukwu shows us glimpses of listening faces. Anthony’s lawyer Marty (Richard Schiff), brings a tenderness to the job as another person who cares about Anthony, providing a friendship to him as much as hope of saving his life. And Michael O’Neill, as Chaplain Kendricks, offers a sense of the spiritual peace that comes with such a job, as if a lifeline for Warden Williams as someone who has also seen the same horrific things that she does on a daily basis. Chukwu unites these characters, vivid and excellent roles for each of these actors, under the theme of finality—all of them proclaim to Warden Williams that they want to retire, as if they have reached their own end with being in the same world as capital punishment.

“Clemency” is that little miracle of filmmaking, a story that answers to unthinkable tonal and narrative challenges it sets for itself by providing a clear vision. The cinematography by Eric Branco becomes its own life source, finding expressive lighting and framing within the drab setting of a prison, making corridors of cells seem all the more endless. Chukwu's film is further proof that great moviemaking is the key to bringing audiences into profound, somber head spaces and places of employment.

from All Content http://bit.ly/2BiY3rX

0 notes

Text

Recension av Stadsdelen av Gonçalo M. Tavares

Tavares’ sketch of the neighborhood, detail

In The Neighborhood, Tavares gathers some of literature's most outstanding authors, or rather his own impressions of them from reading their works, and places them all in the same part of his imaginary town, in the same time frame. In this neighborhood, men like Valéry, Calvino, and Swedenborg live their lives, all with their special quirks and ideas.

The book is both an experiment with literary figures, and a wonderful play on poor logic. Tavares' characters tend to apply strict, theoretical logic to real, chaotic life, making the logic itself exaggerated, distorted, and finally completely illogical. A significant part of the book revolves around this deteriorated state where common sense that's been stretched too far ends up, and it's a lot of fun. Especially Valéry and Swedenborg live their lives in a world where logic can be applied to anything from love and seduction to depression and empathy, with absurd consequences. The rational and reasonable becomes nonsensical in the hands of Tavares.

However, Tavares keeps walking the edge between the absurd and the cliché. Which side he ends up on seems to correlate with the amount of seriousness he puts into his subjects. Those that fall flat all have traces of an attempted profundity, closely followed by the resulting superficiality. The worst offender of this is Mister Calvino. Tavares seems like he can't decide if he wants to parody the types of Coelho and their distinctive, pseudo-self help style, or if he wants to imitate them. When he leans toward the latter, we get clever but ultimately meaningless tales, seemingly completely void of self awareness. On the other hand, the clichéd bits are mixed up with others that are genuinely brilliant, where Tavares throws seriousness and pretensions out the window and simply laughs in our faces. In those moments, The Neighborhood is absolutely magical.

Gonçalo M. Tavares

Mister Brecht is one of those amazing parts where everything just works. Here, Brecht is an Aesop-like figure, if Aesop had been a drunkard, twisting his fables into bitter, uncomfortable parables that sometimes border on the offensive. The absolute zenith of The Neighborhood is Mister Eliot, the densest chapter in the book, where the Eliot of Tavares' fantasies is giving lectures on various verses of famous poets, trying to make some sense out of them. This is absolutely hilarious. Eliot attempts to find ways of making the dismembered poems "saner, more reasonable", finding "logical and sensible alternatives" to the artistic, abstract verses. He treats them as something tangible, analysing their parts and words trying to find something concrete. The very matter-of-factness with which this is done is absolutely wonderful, and reads like playful mockery of those who try to apply the rules of the every-day to literature. This is the way I wish Tavares would write more often.

Ultimately, this seems to be a running theme in the stories of the "misters": logic meets art. Are they really as incompatible as they might seem at first glance? Tavares answers no, and shows us why, especially in the chapters of Misters Eliot and Swedenborg (where the Swedish philosopher and theologian tries to interpret reality by sketching geometrical shapes and their relationships). In this fictional town of Tavares, logic and abstract literature are tightly wound together, and maybe we'll find something completely new in the resulting chaos. The Neighborhood is very hard to rate. The different chapters are pretty inconsistent, and a lot of it is hit-or-miss. At its best, Tavares' writing is fanciful and completely absurd. At its worst, its pretentious. However, the good parts left me wanting more, and so I will definitely seek out some of Tavares' other works. If he is regularly anywhere near his best, I have a literary treasure to look forward to.

(The version I've been reading is a Swedish translation published by Bokförlaget Tranan, and includes the stories of Misters Valéry, Brecht, Eliot, Juarroz, Swedenborg, and Calvino. Hans Berggren's translation seems solid.)

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Hans Berggren och släpptes 2012 av Bokförlaget Tranan. Recensionen ligger sedan 2014 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

0 notes

Text

Contemporary Art & Its Histories Part 2

Despite Hirst’s impassive and disinvolved artistic demeanour and public image, he has a habit of wearing his influences on his sleeve quite boldly, even to a point of possible plagiarism. The same wholly goes for his thematic motifs, a limited range of concepts that almost exclusively involve elements of faith, science, value, and most famously, mortality. His conceptual scope is best described by art critic Sarah Kent who said: “Hirst alludes to heavy topics – health, meaningful living/living death, art as a live entity, the extinction of the individual and the species – with a brilliant, angst-free clarity.” (Kent, 2012).

With the previously discussed For the Love of God, the thematic inspiration is apparent, the enigma of death (in the form of the skull) juxtaposed with the concept of value and preciosity in our society (represented by the diamonds). This quite plainly stated juxtaposition of themes is not an invention of Hirst’s, but is him using a well know theory and practice in the art canon, memento mori. Memento mori (meaning “remember that you have to die” or simply “remember death”) is a Latin Christian theory which revolves around reflecting and being aware of one’s own mortality and, as a result, the transient nature of all physical goods and earthly life which. As an idea it can be traced to the Plato’s dialogue Phædo which recounted the trial and execution of Socrates during his last days, specifically his philosophical lamentations on death and the afterlife. He culminated his thoughts in his discussion on philosophical practice as a whole and described it as: “about nothing else but dying and being dead” (Plato, 360 B.C.E).This philosophical approach to understanding one’s own transient life was manifested in a number of artworks from the classical and early Christian eras all the way up to the modern period, in which the reoccurring objects associated with the still life based theme are adapted to burgeoning and well-established modern methods of artistic representation and style. Now wilting flowers, rotting fruit, near-finished hourglasses, and almost always a signature inclusion of a skull were updated by the new masters and given (ironically) a new sense of life.

Famous modernist works that utilize the thematic imagery of memento mori include Francis Picabia’s oil-on canvas cubist work Portrait of a Doctor and Pablo Picasso’s proto-cubist lithograph Black Jug and Skull (1946) which follow the more traditional artistic sensibilities of previous vanitas works, too much more avant-garde and disconnected works that still hold a common thematic resonance such as Jana Sterbak’s Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic (1987) and Robert Rauschenberg’s Animal Magic (1955-59), all of which involve some element of death juxtaposed with the fleeting physical frivolousness of earthly possessions and the dissonance between them.

An artist whose work captures the element of still life and memento mori well is post-impressionist Paul Cézanne, whose oil paintings during his final period and up to his death in 1906 encapsulated the sense of reflection on his ephermility and inevitable demise that was seen in Plato’s account with Socrates, but where Socrates created dialogue, Cézanne painted. Between the years 1890-1906, Cézanne became withdrawn from portraiture as a result from multiple afflicting events that briefly caused him to leave his usual dwelling of Paris for his hometown, Aix-en-Provenance. Described by Harris (1983) his life was “…outwardly uneventful. He seemed to have been forgotten by the art world, and ceased even to submit his works to the Salon [Salon des Refusés]”. During the final years of his life Cézanne’s isolation was only interrupted by various letters he would send to multiple of his subjects, reading these letters reveals an increased consideration to the artist’s own mortality: "For me, life has begun to be deathly monotonous"; "As for me, I'm old. I won't have time to express myself"; "I might as well be dead." (Cézanne, 1897, 1900, 1905) During the same timeframe his mother passed away and his own heath began deteriorating, both factors being thought as to accelerate his lamentations on death. His climatic resignation of his own life inspired a number of still life watercolours and oils which visually approach the theology and imagery of memento mori. This small series of skull paintings have become some of Cézanne’s best known works, not only for their assaulting yet near-domestic arrangement and deeply personal visuals that almost seem like the skulls were painted as portraits rather than still lifes, but the intriguing and tragic context behind the paintings enhances their visual aspects thoroughly.

On the aspects of still life, it remains another example of an inspiration towards the previously mentioned contemporary artwork that deserves its own discussion. The quite visually sparse and ultimately singular For the Love of God isn’t comparable to the impressionist work of the latter discussed Cézanne, nor the later cubist arrangements of Picasso, both of which are visibly loud and dramatic. Hirst’s work, despite the inclusion of radiant collection of diamonds, is quite tonally subdued and constructed of only a few colours on the brighter side of the monochromatic scale, paired with the sparse use of space, a tightly bunched visual point presented with a lot of surrounding area that creates a certain inflated level of draw towards the main appeal of the piece. This class of visually thinly populated still life became a visible trend in the modernist period, particularly by one artist: Giorgio Morandi. Painter and printmaker Morandi specialized near exclusively in painting still lifes of mundane, decorative objects such as jugs, bottles, vases, bowls, cans, and boxes, all of which were distinguished for their tonal subtlety as well as their unusual, bunched composition of objects tightly gravitated to the direct centre of the painting. Morandi’s mid-1900’s still life works straddle a border between the relatable imagery of modern realism, and the unrecognizable surrealism of the Metaphysical art style, in essence the painting resonate with the viewer due to their understanding of how such objects can exist and be juxtaposed together, but the visual elements of Morandi’s rough near-impressionist style brushwork paired with the filtered and dulled pigments he used to construct the painting adds a certain level of disconnect within the observer. His particular technique and composition is described well by sculptor and contemporary follower of Morandi Tony Cragg (2006): “Artists’ show through their strange ways of life, their physiologies, the processes they go through, they show us something about our rough generalised pictures of realities, they show us something specific, and a new way of seeing. And one can imagine that the world would be a much poorer place without his [Morandi’s] work…”

When creating art a singular inspiration is difficult to pin, and with For the Love of God, there is ultimately too much both visually and thematically to associate with one singular artist or work, but there is undoubtedly a connection with the famous instances of still life artwork in the modern period, both in the thematic standing of Hirst’s works as well as the visual elements he used.

Bibliography

Books

Bostock, D. (1986) Palto’s Phaedo. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Harris, N. (1983) The Art of Cézanne. London: The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited

Cézanne, P. (1897). Letter to Joachim Gasquet. [letter] Translated by Danchev, A. The Letters of Paul Cézanne. London: Thames and Hudson Limited.

Cézanne, P. (1900) Letter to Paul Cézanne Junior. [letter] Translated by Danchev, A. The Letters of Paul Cézanne. London: Thames and Hudson Limited.

Cézanne, P. (1905) Letter to Émile Bernard. [letter] Translated by Danchev, A. The Letters of Paul Cézanne. London: Thames and Hudson Limited.

Coldwell, P. (2006) Morandi's Legacy: Influences on British Art. London: Philip Wilson Publishers

Internet Sources

Savvine, I. (2018) Paul Cézanne Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works. The Art Story. [online] Available at: http://www.theartstory.org/artist-cezanne-paul.htm [Accessed 17th April 2018]

n/a. (2001) Paul Cézanne. Wikipedia [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_C%C3%A9zanne [Accessed 17th-18th April 2018]

Archino, S. (2018) Giorgio Morandi Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works. The Art Story. [online] Available at: http://www.theartstory.org/artist-morandi-giorgio.htm [Accessed 18th April 2018]

n/a. (2004) Giorgio Morandi. Wikipedia [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giorgio_Morandi [Accessed 19th April 2018]

0 notes

Text

Game Review: Zero Time Dilemma

Zero Time Dilemma is an interactive novel/puzzle game concluding the Zero Escape trilogy. It’s out now on PC, PlayStation Vita and Nintendo 3DS. Alan Stock staves off Zero’s memory-loss drug to bring you this spoiler-free review for ComiConverse.

Game Review: Zero Time Dilemma

Virtue’s Last Reward (VLR), the previous instalment in the Zero Escape series, left me desperate for more of this compelling saga. I was addicted to the twisting, complex storylines, great scenarios and memorable characters of these interactive novels. I quickly picked up Zero Escape Dilemma to finish off the storyline – kept hanging from the unresolved ending of VLR. I was curious whether the appeal of the deadly Nonary Games could survive yet another rehash. I was happy to discover that creator Kotaro Uchikoshi manages to keep the series fresh, pander to his fans and tie up loose plot ends, despite some flaws.

The sinister Zero. Credit: Chime

First, a bit of history. It’s actually a miracle that Zero Time Dilemma was made at all. The backstory behind the game’s creation is a tribute to the power of social media. The previous titles in the series; 999 and VLR, hadn’t been very commercially successful. But when passionate fans heard that Uchikoshi’s wish to finish the series was being dismissed for financial reasons, Zero Escape lovers worldwide banded together. They began an online grassroots movement called “Operation Bluebird”, gaining thousands of supporters. This collaborative effort persuaded the publishers to continue Zero Time Dilemma’s development, and reportedly Uchikoshi even used a fan-made vocal track based on a song in VLR during his pitch for the game. It’s a heartwarming tale in the financially cut-throat world of the games industry. Developers Chime included a special message thanking their fans for making the game possible in the credits and Uchikoshi is forever brimming with praise for his loyal fans.

Credit: Chime

For anyone who hasn’t read my previous Zero Escape reviews – what are these games? Primarily they’re interactive novels, with lots of character dialogue and twisting, intertwined plotlines. Breaking up the narrative are escape-the-room puzzle sections, where you explore a small area, solving devious puzzles in order to progress and see the next section of the story. But what makes this saga special, apart from the quality writing and interesting characters, is the clever structure of these games.

During the story, you get to make important decisions – such as who to team up with, or where to go next. The games have multiple endings, and in order to see them, you are able to hop back to decision points in the story and choose different outcomes to see how things change. You can visualise this as a branching flowchart of different possible timelines, which the games let the player see. Some endings can only be accessed by learning information from one timeline, giving you answers allowing you to progress in a different timeline. The idea of multiple timelines, choice and consequence are all tied into the crazy, sci-fi themed narrative.

The tip of the iceberg of the complex timeline trees in the game. Credit: Chime

Zero Time Dilemma continues where VLR left off. I won’t spoil any of these games for you, but be warned that Zero Time Dilemma contains some pretty heavy spoilers for both VLR and 999. Playing them first is highly recommended especially as they’re both brilliant games. The story’s premise this time around will be familiar to anyone who’s played these titles. Nine unfortunate people are imprisoned by the masked villain Zero in a mysterious facility and must play deadly games in order to escape.

The more realistic look of the protagonists really gels well with the subject matter, but preserves the great character design of the previous games. Credit: Chime

Unlike previous games, most of the nine victims already know a bit about each other – they are candidates for a simulated Mars mission who have spent a week getting to know each other. Some returning characters from the series are present – their goal: to foil catastrophic events that will happen if they don’t intervene. Zero has drugged and locked up the cast in an underground bunker explaining the game has “the fates of you, me, and the human race in the balance.” The rules of the game: a single door allows escape, but the only way to unlock it is to enter six passwords. When someone dies, a single password is revealed. So, in order to escape, at least six of the players must die. Each player wears an immovable bracelet, and every 90 minutes, it injects a memory-loss drug into them, making them forget what happened.

Damn Zero, not again! Credit: Chime

This time around, the players are split into three teams, isolated from each other in different wards of the bunker. Each team is put through various trials including the deadly escape-the-room games. In contrast to other Zero Escape games, you view events from a third person perspective instead of playing as one of the protagonists. Your viewpoint hops between the three teams as you see fit.

Mistrust is heavy in the air. One of the nine is an unknown boy called “Q” wearing a bizarre helmet covering his head, who claims to have amnesia. Who is he? Zero’s messages are pre-recorded – could he be among the players? Zero encourages players and teams to betray each other at every turn, to sacrifice others to save themselves. As events turn sour, people die and mysteries thicken.

Q, pictured here, is a great character. Who lies beneath that helmet? Credit: Chime

The dark tone of 999 returns, with a lot of gore, death, shock and plenty of unsettling moments. The atmosphere is thick. It’s even more reminiscent of the movies Saw and Battle Royale than previous outings – no bad thing. But humour’s still present, providing some light relief from the dark – although thankfully it’s been a toned down in quantity compared to 999 and VLR, befitting the serious predicament of the players. The game gives you plenty of difficult decisions, such as who to execute in a no-win situation. Some of these choices must be made within a tight time limit, adding an extra sense of urgency.

I sense this ain’t gonna end well… Credit: Chime

To give an example of the hard decisions and tone of the game (minor scenario spoiler ahead), one memorable escape-the-room scene is also featured as Zero Time Dilemma’s box art. One team is locked in a room. Within, a girl is trapped in a trash incinerator, which is about to start up and burn her alive – with no hope of escape. A man is held strapped to a chair outside the incinerator, a revolver fixed on the frame, muzzle pressed against his head. The gun’s chamber spins – 3 out of 6 of the bullets are live rounds. The last player, a girl, is given a choice that you must make for her. The time before incineration is about to end. The sound of the revolver firing will unlock the incinerator and free the girl inside. Don’t shoot, and she’ll burn. Shoot, and there’s a 50% chance that you’ll blow the brains out of the guy in the chair (due to half of the bullets being live). During this deadline, the characters appeal frantically for you to choose one option or the other. You have only 10 seconds to choose – and you must live with the consequences. Someone will probably die – but who?

Critical decisions are highlighted with much fanfare, a far cry from the stress-free “choose your room” options from earlier games. Credit: Chime

These tense moments are elevated through excellent music. Their impact is also helped by the characters being 3D and animated within the world in this instalment, rather than just overlaid on a flat background. The character animation and facial expressions are stiff (forgivable given the game’s handheld roots), but still make the story much more engaging, together with the cinematic camera angles. The English voice acting is a bit hit-and-miss; some characters are brilliantly voiced, like newcomer boy “Q” who puts to shame the awful child’s voice performance in VLR. But others really don’t hit the mark, either through poor delivery or the voice not really fitting the character. Zero himself is also very quiet in the mix – I recommend turning up the voice volume immediately, or even using subtitles to hear what he’s saying. Fortunately, the writing and translation work is once again excellent. The characters are on the whole are even more believable and likeable than the previous games, feeling much more like real people than the caricatures we’re used to in Zero Escape.

Inside one of Zero Time Dilemma’s many escape rooms. Credit: Chime

The escape rooms are as devious as ever, with some good puzzle design – fortunately not hitting as many difficulty spikes as Virtue’s Last Reward. The room designs tie in nicely with the concepts and themes of Zero Time Dilemma. Continuing Zero Escape tradition, interesting and complex scientific or philosophical theories are explored throughout the story – the game touching for example on topics like the Sleeping Beauty Problem, and Monty’s Dilemma. These brain teasers get the characters (and you) musing about what exactly Zero and his game’s purpose really is – and are great food for thought. They also have a bearing on Zero Time Dilemma’s bold timeline structure.

Puzzles range from the straightforward, like this one, to the more devious. In general their design is good and there’s some good head-scratchers throughout. Credit: Chime

The addition of memory-loss drugs to the story affect the game’s structure in an interesting way. Instead of progressing through the plot in a linear fashion like the last games, here it’s broken into “fragments” that each team experiences. You pick a team, then choose one of the many fragments available, with only a thumbnail image hinting at what it may contain. You play through the fragment and at the end the team is usually injected with both sleeping and memory-loss drugs. The cycle continues – pick a team, play a fragment. After you’ve experienced certain events, more fragments will unlock.

The fragment select screen. Credit: Chime

This means the order in which you experience events will be very different (at least in the first few hours) between players of Zero Time Dilemma. It feels like the movie Memento: you experience the story in the same way that the game characters do – waking up in a situation each time with only a vague idea of when it’s happening, and what horrors might have already occurred but which you’ve forgotten. Of course, the more fragments you play, the more you begin to piece everything together. One fragment may answer mysteries you found in a different fragment – making the narrative experience different for each player until the game becomes more linear. It’s a great idea, but not without its flaws.

Sadly gone are the clever bracelet ideas from the last games, instead they serve just as a device to inject the drugs, and helpfully double up as a watch. What a nice guy Zero is. Credit: Chime

The fragment structure makes the first part of the game a disorientating experience, which is, of course, intentional, but this loss of coherency makes it difficult for the game to build tension and maintain a good narrative pace. It’s only in the later part of Zero Time Dilemma when more linear events start rolling that the story really gets you hooked. Before then, you’re hopping between fragments with the plot a confusing mess of random events with unclear connections. Curiosity will keep you playing, but it’s when the plot becomes less fragmented that the game’s at its most enjoyable. Then you’ll find it very hard to put down. Another problem with the fragment structure is that the game is front-loaded with escape-the-room sections – because most of these are fragments unlocked from the start. Once you’ve seen them, the rest of the fragments play out mostly as interactive narrative meaning the gameplay takes a back-seat.

This game is not for the faint-hearted – there’s some pretty gruesome stuff in here, even if it is cartoonish gore. Perhaps it would have more impact if it was more subtle like 999’s glimpses and descriptions of horrific scenes. Credit: Chime

An in-game flow chart is available to help you track events, timelines, and spot decision paths you’ve missed. However, I found this to be a bit of a lazy crutch and thought it was much better fun to try and piece together the fragments for myself. As the story unfolds, you start to link which fragments occur in which timelines, and you’ll eventually see some of them to their conclusions. After a few endings, in true Zero Escape fashion, the plot goes completely haywire and loads of crazy things happen one after another. Twists and revelations abound, questions are answered, more are raised. All the story strands ultimately intertwine brilliantly. There are even clever puzzles associated with the game’s structure, but I can’t really talk about these without spoiling it for you.

The location design is industrial and fairly boring – the space lacking the flair of 999’s cruise liner setting. Credit: Chime

Unfortunately, there are some story sticking points – locked narrative gates where the game does a poor job of communicating how to progress further. Two in particular spring to mind, where I had to check online how to proceed – I found many others had the same problem. The plot’s fragmentation although interesting, does hurt the game somewhat. Some of the twists and plot resolutions are also either ludicrous or quite hamfisted. Some fans will be annoyed at the how events are wrapped up, and won’t be happy with new plot devices that were introduced to bring this complex trilogy to a close.

The inventory is finally easy to use compared to the previous games, although it’s implementation is still somewhat clunky. Credit: Chime

The final ending will probably disappoint some players, and it’s worth pointing out this is a significantly shorter game than VLR, clocking in around 20-30 hours depending on how many of the fragments you re-play. Some of these problems are due to the time restraint of the game’s short development – half of the writing and event design were done by other people than Uchikoshi (who wrote the entirety of the last two games) and it shows. It’s also important to note that the PC port makes no effort to update the user interface to reflect the changed control scheme, handheld console icons are everywhere – and it has control and performance issues throughout, a poor effort.

Carlos seems like your a boring pretty-boy jock at first, but he really grew on me. Credit: Chime

But overall, regardless of the platform you play on, Zero Time Dilemma is still a highly engaging story that really gets its hooks into you. Some of the plot strands are brilliant and there are plenty of heart-stopping moments, brilliant revelations, clever ideas and “what the heck?!” bombshells. This is what Zero Escape is all about. Add in the new emotive characters, great soundtrack and cinematic direction and it’s really the pinnacle of the overall series in terms of a polished, engrossing movie-like experience. There’s more urgency and pace in this instalment. Zero Time Dilemma feels distinctly different from the previous games, which is good. But unfortunately, partly as a result of the pacing and the fragmented structure, the plot and overall immersion don’t quite live up to its predecessors, even though at times it’s fantastic.

No Zero Escape game would be complete without a ridiculously sexy lady with everything on show – fortunately, the other girls in the game show a lot more class, with Mira here being the least interesting of the bunch. Credit: Chime

Zero Time Dilemma finishes off a superb trilogy with a bang. Crucially, it tries a different angle and attempts to mix up the formula a bit. The return of darker, more serious content is welcome, adding the gritty edge that VLR sorely lacked. It takes a while to warm to, but once you get into it, you’ll find it impossible to stop playing and you’ll want answers to all your questions. It’s with a heavy heart I must bid farewell to the colourful cast and intricate plot of this great series – and I can’t wait to see what Uchikoshi does next.

The post Game Review: Zero Time Dilemma appeared first on ComiConverse.

0 notes