#UNFCCC COP 25

Text

Climate summit host Spain struggles on environment

#ClimateSummit host #Spain struggles on #environment #ClimateSamurai #Climate

Spain wanted to make a splash on the international scene by agreeing to host next month’s COP25 climate summit at the last minute after Chile pulled out.

But experts say green issues have not been a priority in the country, which has a poor environmental track record.

Only 2.3 percent of all Spaniards consider the environment as one of the country’s main problems, according to the latest…

View On WordPress

#cliamte news#Climate#climate accord#climate action#climate agreement#Climate Challenge#climate change#climate change challenges#climate news#spain#Spain Climate change#UNFCCC COP 25

0 notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from Climate Change News:

Chile plans to use this year’s UN climate talks to focus attention on the world’s most important carbon sponge – the oceans.

Oceans mop up vast amounts (up to 80%) of the CO2 emitted into the atmosphere by humans. The ecosystems they support could provide new, albeit controversial, ways to draw carbon from the air.

But their health and management remains sidelined from the key political forum on climate change, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

That could change this year. Host nation Chile, which has control over almost 18 million sq km of the world’s oceans, is calling this year’s Cop25 UN climate conference in Santiago a “Blue Cop”.

“Time is running out,” Chile’s environment minister and the Cop25 president Carolina Schmidt told the meeting through a video. “This is why Chile has been pushing to highlight this problem. In our vision, there cannot be an effective response to climate change without a global response to ocean issues.”

The UN body of climate scientists, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is due to release a landmark report on the complex linkages between ocean and climate change in September. This is expected to add impetus to Chile’s programme.

What it means to host a “Blue Cop” is still up for debate. Rémi Parmentier, secretary of Because the Ocean, an initiative signed by 23 countries at COP21 in Paris to call for the IPCC report, told Climate Home News “the role of the ocean in mitigating climate change, and the ocean change that it is causing (ocean warming, acidification, deoxygenation, etc) will take centre stage, now and in the future”.

“Ocean and climate are two sides of the same coin: if we want to protect the climate, we must protect the ocean, and vice-versa,” Parmentier said.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On COP-26 hinges credibility of UNFCCC process. It must break impasse between developed and developing world

#GS3#ENVIRONMENT#CLIMATE CHANGE#COP26#UNFCCC

CONTEXT

In the next two weeks, a world desperate for climate solutions will be expecting for a significantly better outcome from the UNFCCC's 26th Conference of Parties in Glasgow than the meeting accomplished two years ago.

Agenda of the Summit

The spectacular failure of COP-25 in Madrid — the conference was postponed last year due to the Covid pandemic — to complete the process of framing rules for the Paris Pact despite going over by nearly two days had shed light on the disconnect between global climate diplomacy and the imperative to reduce GHG emissions.

Unchaining the ghosts of the UNFCCC's longest meeting will necessitate breaking the impasse between India, China, and Brazil, as well as the industrialized countries, over the future of carbon markets.

The latter have obstructed attempts to incorporate pre-Paris pact carbon credits into the historic agreement's rulebook, alleging that many of these credits do not adequately represent emissions reductions.

Even for a process that has frequently been found wanting, the Madrid wrangling constituted a new low, owing partly to the industrialized world's refusal to honour its pledges — financial, technological, and emissions-related.

But, much has happened since December 2019 to need that negotiators in Glasgow do more than conclude the unfinished business of Madrid. The weather has become more unpredictable, the pandemic has required connecting the dots between health and the environment, and the world is in the grip of an energy crisis.

An IPCC assessment issued in August warned that the earth might warm by more over 1.5 degrees Celsius over the next two decades, even if nations began dramatically reducing emissions right once.

These catastrophic warnings have focused attention on the Paris Agreement's voluntary framework for reducing emissions, known as Nationally Determined Contributions. The NDCs have long been criticized for being insufficient to avert a temperature rise of more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-Industrial levels — the more conservative of the Paris Pact's determinants.

With a cataclysmic temperature rise predicted much earlier, wealthy countries, led by the United States, which has re-entered the Paris pact under President Biden, have begun to intensify their earlier calls for more global climate ambition.

The majority of discussions in the run-up to COP-26 have centred on the necessity for all countries to agree to a net-zero carbon emissions target by 2050.

Despite the fact that over 130 countries have made varied commitments to achieve carbon neutrality, it remains a difficult issue that divides rich and poor countries.

The legitimacy of the UN climate process is dependent on how it balances legitimate development claims by nations such as India with the crucial need to reduce global GHG emissions.

Conclusion

Historically, India has been an outspoken supporter of climate justice. The escalating crisis will almost certainly result in demands to reduce its claims. The country's negotiators must remain consistent in their refusal to cede development space. After all, India is on track to reach its Paris targets.

0 notes

Text

Unpacking pre-2020 climate commitments - Hindustan Times

Unpacking pre-2020 climate commitments - Hindustan Times

In the last few years, the discussions on climate ambition have primarily focused on either nationally determined contribution (NDC) targets committed within the framework of the Paris Agreement, or respective countries’ net-zero commitments. While these mid-century ambitions are essential for achieving the 1.5°C global warming target set in the Paris Agreement, it is equally important to study the outcomes of the emission reduction pledges made by developed countries before the Paris Agreement, in the pre-2020 climate regime. The fate of post-2020 negotiations for climate change crucially hinge upon the achievements, gaps, and issues recognised in the pre-2020 period.

However, post-2020 ambitions announced by developed countries have been set without due consideration of their past performance. Concerns continue to be expressed about the implementation of pre-2020 commitments by developing countries and were most recently emphasised in decision 1/CP.23. The issue was also discussed at the 25th Conference of Parties (COP 25) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The cost of unmet climate commitments by developed countries

The significance of pre-2020 climate actions by developed countries can be broadly encapsulated across three dimensions: environmental, political, and economic.

Environmental: The World Meteorological Organization highlighted that the global carbon dioxide concentration has already exceeded 410 parts per million (ppm), impacting our ecosystems, marine life, and increasing the global average temperature to record high levels (WMO 2021). There is a 40% chance that the annual average global temperature would exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels in the next five years (WMO 2021). This 1.5°C marker is identified as a key tipping point1 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) beyond which environmental risks are likely to be extreme (IPCC 2018).

Political: The gaps in pre-2020 climate actions are also of grave concern from an equity perspective. The developing countries have concerns of bearing the burden of tackling the mitigation gaps from the pre-2020 period in the future. Furthermore, it has caused a further fissure between the developed and developing country groupings, contributing to mistrust on the next set of ambitions that were tabled in the negotiations.

Economic: The cost of mitigation efforts is expected to increase significantly in the future compared to the pre-2020 period. According to the World Economic Forum, inactions towards climate change would cost the world $1.7 trillion per year by 2050 (Januta 2021).

Based on the principle of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC), the onus to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for a long time was placed on developed countries (also referred to as Annex I Parties). This principle was operationalised within the UNFCCC through two international climate agreements: the Kyoto Protocol (1997) and the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol (2012). Both these agreements assigned quantified emission reduction targets to developed countries, based on their 1990 emission levels. Under the Kyoto Protocol, an emission reduction target of 5%, based on 1990 levels, was set to be achieved by developed countries in the first commitment period (2008–2012). In contrast, under the Doha Amendment, it was agreed that an emission reduction target of at least 18% would be met by developed countries in the second commitment period (2013–2020).

Mapping emission mitigation achieved by developed countries in the pre- 2020 period. Research focusing on emission reductions in the pre-2020 period has been scarce. As a result, there is little clarity on the performance of developed countries under the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment. To fill this gap, CEEW has undertaken a review of mitigation outcomes for all developed countries vis-a-vis their overall commitment under the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment and the results are presented in this report. This first-of-its-kind accounting evaluation conducted in a developing country seeks to provide a clear picture of the performance of developed countries in the pre-2020 era. It does so by identifying areas of accounting concerns, gaps in achievements vis-à-vis set targets, and based on these, sets forth a framework for easy comparisons among mitigation achievements of developed countries. The key findings of our study are highlighted below.

Pre-2020 outcomes characterised by poor participation and performance

The implementation of the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment witnessed several setbacks. Several developed countries did not participate in these climate agreement discussions. The lack of participation resulted in the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol not coming into force for almost its entire duration (before December 31, 2020).

In the first commitment period (2008–2012), a total of 36 Annex I countries and the European Union pledged emission reduction targets. Some of the notable exceptions were the United States (US) and Canada. Furthermore, Cyprus, Malta, and Kazakhstan were not included among Annex I countries during the first commitment period and so have been mentioned among the non-participating countries in Table ES1. In the second commitment period (2013–2020), the participation fell significantly as other large emitters like Japan and the Russian Federation did not accept the new emission reduction targets of at least 18% compared to their base year levels.

Furthermore, the countries that participated in the discussions on these two agreements also misused the existing accounting provisions to achieve their targets. The outcomes of our study provide a grim picture of the emission reductions that have been achieved by developed countries since 1990. The greenhouse gas emissions from Annex A sources for all Annex I Parties (both industrialised and economies in transition [EIT] countries) declined only by about 14.8% in 2019 compared to their base year emissions levels. This reduction is quite low considering the emission reduction targets were set at a minimum of 18% below the 1990 levels to be achieved by 2020 under the Doha Amendment. More dramatically, the non-EIT Annex I Parties (majorly comprising industrialised countries) witnessed a meagre emission reduction of 3.7% by 2019 compared to their base year emissions levels. Thus, the 14.8% emission reduction was made possible largely due to the contribution of EIT countries, which collectively showed a decline of about 39% below the base year emissions levels.

The impressive 39% reduction in emissions achieved by the EIT countries is not due to emission reduction measures undertaken by them but were due to the economic downturn in the 1990–1997 period, during which the emissions declined by 38%. The economic shock suffered by these countries was the outcome of their transition from a centrally planned economy to a market-based economy. This led to the generation of unearned emissions allowance (equivalent to about 28.4 GtCO2eq) acquired by these countries in the 2008–2020 period. These unearned emissions allowances are also referred to as ‘hot air’, resulting from inflated base year emissions.

Also, the non-participation of the US in both the commitment periods adversely affected the global climate action in more than one way. The United States emitted about 11 and 26% more than their estimated emission allowance in the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment, respectively. Citing US non-participation as the reason, Canada and Japan also withdrew from the climate agreements. New Zealand and the Russian Federation also did not accept new targets in the Doha Amendment. This led to additional usage of carbon space of about 10.9 GtCO2eq by non- participating countries than their estimated emission allowance in the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment. Also, Annex A emissions from the non-participating countries represented about 47% (41.3 GtCO2eq ) in the first commitment period and 71% (96.1 GtCO2eq) in the second commitment period of the total commitment period emissions by all developed countries.

In contrast, the participating countries, especially the European countries, seem to have performed well and emitted significantly less than their emission allowances in the aggregated pre-2020 period. France, Spain, Italy, and the UK collectively are estimated to have unused (left-over) emissions allowance of about 2.3 GtCO2eq by the end of 2020. And collectively, the participating countries have unused carbon space of about 14.4 GtCO2eq. However, these apparent overachievements (14.8 GtCO2eq) of the participating countries are the outcome of unearned emission allowance due to the selection of inflated base year and inclusion of deforestation emissions in their base year emissions. Australia primarily benefitted from adding deforestation emissions to its base year emissions and gained unearned emissions allowance equivalent to 1.4 GtCO2eq.

If the total unearned emissions allowance (14.4 GtCO2eq) of the participating countries is considered, then the overachievement of the participating countries in the 2008–2020 period is almost nullified. On extending these accounting criteria to the non-participating countries, it is observed that, collectively, both the participating and non-participating Annex I countries, under the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment, have emitted about 25.1 GtCO2eq more than their estimated emission allowances in the 2008–2020 period.

Pre-2020 climate actions: ranking the developed countries

As an extension of the pre-2020 analysis, The Council has ranked all the 43 developed countries based on its sincerity and performance in mitigation efforts during the pre-2020 period. This ranking system developed by The Council is unique as it explicitly focuses on the pre-2020 climate agreements: the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol. The purpose of this ranking is threefold:

(1) to provide an independent and comprehensive evaluation of the efforts undertaken by developed countries towards meeting their pre-2020 targets;

(2) to enhance transparency by enabling an easy comparison of pre- 2020 performance among developed countries; and

(3) to identify developed countries that have been climate champions in the pre-2020 period.

In order to compare their pre-2020 mitigation performances, Annex I countries were analysed and rated on their seriousness and faithfulness towards climate action (sincerity), as well as the overall mitigation performance (action) in the pre-2020 period. Figure ES2 highlights the indicators and broad categories against which Annex I countries were analysed and rated.

The ranking reveals that European countries have performed relatively better than non-European countries. Sweden leads the overall action indicator performance with a score of 95%, followed by the UK, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, and the Netherlands. While most of the EIT countries fall in the middle of the ranking order, the non-participating developed countries are placed at the bottom. Some major economies such as the Russian Federation, Turkey, Canada, and the US have scored around 50% and less.

Our ranking makes it clear that developed countries have performed at various levels with respect to their emission reduction targets in the pre- 2020 period. Also, the additional consumption of carbon space (25.1 GtCO2eq) is quite significant and needs to be addressed in order to limit the temperature below 1.5oC by 2100. However, the burden of these gaps emerging from the pre-2020 period should not be transferred to developing countries but distributed among developed countries themselves. Hence, the non-EIT Annex I countries, especially the non-participating countries, should consider revising or enhancing their future targets.

Another way to bridge this pre-2020 gap would be developed countries, which did not participate in the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment, purchasing the unsold certified emission reductions (CERs) and voluntarily cancel the unearned carbon emission allowance. This would be a win-win decision for both developing and developed countries because it would not only increase the demand of CERs in the sluggish market but also help developed countries comply with their pre-2020 targets without carrying them forward (post-2020 period).

Further, it is imperative to strengthen the accounting and compliance mechanism to fill the existing loopholes and ensure misuse of accounting does not occur in the post-2020 climate regimes. The accounting provisions should reflect environmental integrity and should not be curtailed at the convenience of the participating countries. Finally, the easy exit of countries from climate agreement should be restricted as it not only results in additional burden but also undermines the trust in the process of negotiations itself and dissuades other nations from undertaking ambitious target.

The study can be accessed by clicking here

(The study has been authored by Sumit Prasad, Spandan Pandey, and Shikha Bhasin)

.

Source link

0 notes

Text

摆脱贫困和减少碳排放不可得兼,我们还有希望阻止全球变暖吗

50年来,世界所取得的经济上的巨大发展是以地球的长期宜居性为代价的。罗马俱乐部时任主席奥雷利奥·佩切伊曾去往达沃斯,并在1973年年会上向与会者发出警示,称我们已经达到增长的极限。“如果经济和人口继续以现在的速度增长,那么即使拥有先进的技术,地球上环环紧扣的资源——我们都生活于其中的全球自然系统,也就顶多支撑到2100年。”他这样说道。回过头来看,这一看法被证实非常有先见之明。

作为一个组织,世界经济论坛一直坚持把气候变化提上年会议程,但这还不够。我们曾经取得过一些成就:在世界经济领袖非正式会议(IGWEL,一小群政界和商界领导人每年在世界经济论坛上的会面)上,我们迈出了在里约热内卢举办1992年联合国地球峰会的第一步。从20世纪90年代末开始,达沃斯年会成为商界人士和公民社会成员会面的安全场合,尽管环保活动家和跨国公司之间的公开敌意与日俱增。2015年,第21届联合国气候变化大会(COP21)在巴黎召开前夕,一大批全球最大企业的CEO为《巴黎协定》的签署铺平了道路。在一封公开信中,他们承诺“采取自愿行动,减少环境足迹和碳足迹;制定目标,减少温室气体排放和/或能源消耗,同时在供应链和行业层面开展合作”。从本质上讲,他们传达出了这样的信息:他们不会阻碍任何政治协定的达成;���反地,他们意在支持这种协定。尽管如此,无可辩驳的是,我们这些政治、商业和社会领导人在应对气候变化方面做得很失败。为什么会发生这种情况呢?我们应该怎样推动世界扭转这一局势呢?要回答这些问题,重述过去200年来的全球经济发展历程至关重要。正是在这一时期,温室气体被大量排放,如今正在对环境造成不可修复的破坏。正是在这一时期,对环境问题的担忧被当务之急取代,而这些所谓的“当务之急”在如今看来已没有那么重要。我认为,我们只有先理解这一事件��后的逻辑,才能改变经济体系发展的动态机制。

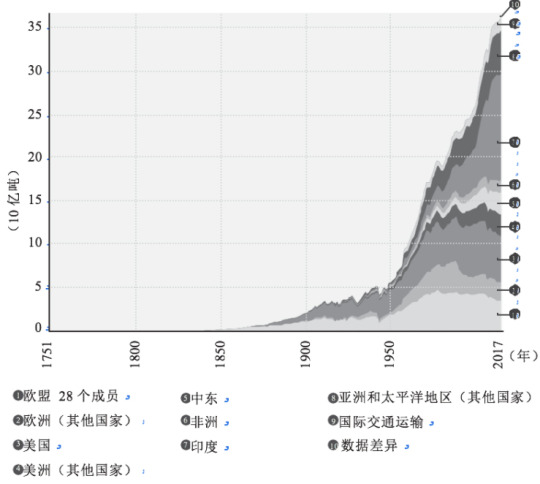

我们无法回到过去,询问先辈为何如此热衷于会导致气候变化的经济活动,但答案不难猜测。从“用数据看世界”(Our World in Data)网站提供的可视化数据可以看出,大概在第一次工业革命蓬勃发展时期,全球温室气体排放开始加速。二氧化碳、甲烷等温室气体能够吸收并释放红外辐射。这些气体是通过燃烧化石燃料产生的,并且聚集在地球大气层中。在第一次工业革命开始后的150年里,火车、轮船、工厂遍布北美和欧洲这两个世界上工业化程度最高的地区,它们所赖以提供动力的发动机几乎无一例外,都是靠燃烧煤炭或者其他化石燃料运转。我们现在知道,煤炭等化石燃料的燃烧正是导致所谓的温室效应的罪魁祸首——大气层中的温室气体吸收来自太阳的辐射热量,并将其锁在大气层中,从而使地球表面变热。那时也有人担心环境问题,多数是担心从烟囱中喷出的气体会危害人体健康。事实上,人们最初开始迁移到达沃斯这种位于阿尔卑斯山上的小镇,正是为了躲避严重的空气污染。他们觉得山上的空气更健康,能够治愈肺结核这类疾病。在19世纪和20世纪的欧洲,肺结核是导致人类死亡的主要病症之一。但直到1988年,人为污染会导致全球变暖的观点仍十分罕见,以至登上了《纽约时报》的头版新闻。

从那之后,应对气候变化的斗争的确势头猛增。在1989—1991年,随着苏联解体、冷战结束,迎来了全球合作机遇。在1992年于里约热内卢举办的联合国地球峰会上,气候变化问题有史以来首次成为国际大会的首要议题。正是在这次会议上,《联合国气候变化框架公约》(UNFCCC)被签署,旨在将温室气体浓度稳定在“防止气候系统受到危险的人为干扰的水平”。三年之后,《联合国气候变化框架公约》首次缔约方大会(COP)在柏林召开。1997年,第三次缔约方大会在日本召开,会上签署了《京都议定书》。《京都议定书》要求35个发达国家(包括欧洲的大部分国家、美国、加拿大、日本、俄罗斯、澳大利亚和新西兰)以1990年的水平为参照减少温室气体排放量。该协议自2008年生效。尽管美国和加拿大相继退出,但其他缔约方确实在想方设法减少排放量。不过,它们的共同努力并不足以扭转更大的趋势。全球温室气体总排放量在21世纪第一个10年持续上升,直到今天。尽管《京都议定书》第二期承诺已经启动,还有一份更加全面的新协议(《巴黎协定》)于2015年在巴黎被签署,但仍然无法阻止这一趋势。

“没有一种神奇的发展模式”

这是为什么呢?既然我们对气候变化的严重后果了然于心,为什么还对此无动于衷呢?要回答这个问题,关键的一点在于,那150多个不在《京都议定书》约束性减排之列的国家发生了什么。这些国家被贴上新兴市场的标签,其中包括印度和中国等。1990—2020年,中国创造了历史上最大的经济奇迹。印度尼西亚作为一个受气候变化影响严重的岛国,近几十年来也理所当然地选择了工业化道路。除此之外,诸如埃塞俄比亚等国,在20世纪80年代遭受着饥荒和赤贫,如今的发展轨迹令全球瞩目。应对气候变化重要且紧迫,但为什么行动起来如此之难呢?比起工业化国家,我们更��从这些国家中找到大部分答案。

这首先可以从数据中看出来。正如前文所述,《京都协定书》确实使那些签署国或批准协定的国家做出了改变。总的来说,欧洲(包括俄罗斯)和北美的二氧化碳排放量从1990年的130亿吨减少至2017年的108亿吨,减幅超过15%。但在世界上的其他地区,包括主要新兴市场,以及印度尼西亚和埃塞俄比亚等正在经历工业化的国家,二氧化碳排放量呈爆炸式增长,从1990年的90亿吨增至2017年的240亿吨,增幅高达150%以上。这导致的结果是,全球排放总量在1990—2017年显著增长,从不到250亿吨增至超过360亿吨。

从排放角度来看,这组数据反映的问题十分严重,但从人类发展的角度来看,它体现出来的是一个发展奇迹。在世界各地,得益于国家的经济发展,许多祖祖辈辈都生活在贫困中的人们在过去30年里得以跻身新晋中产阶层。过去,电力、内燃机等近代发明,以及电灯、洗衣机、冰箱、空调、汽车、摩托车等各种衍生的发明成果对于他们而言都遥不可及,但如今这些东西已经渐渐普及。这就是排放量这枚硬币的另一面。要想找到应对气候变化的可持续性措施,而且要能把所有新兴工业化国家囊括在内,就需要考虑到硬币的这一面。

要想理解这一观点,只需去埃塞俄比亚这样的地方,与其经济及政治利益相关者交谈一番即可。你会发现,应对气候变化的核心难题就在于,同一股力量在帮助人们摆脱贫困、过上体面生活的同时,也在破坏着子孙后代在地球上的生存条件。导致气候变化的温室气体的排放不单是工业家或西方婴儿潮等某一代人的自私造成的,而是整个人类渴望为自己创造一个更好的未来的结果。

我的工作所在地是瑞士的一个湖畔城市日内瓦,这让我联想到另外一个湖畔城市——埃塞俄比亚的阿瓦萨。这座城市正在经历转型,与一个多世纪以前的欧美城市或者近几十年的中国深圳等城市的转型十分相似。不久之前,阿瓦萨还是埃塞俄比亚的一个偏远内陆城市,乘坐汽车或者飞机都很难到达。那里几乎没有高速公路,即便有也崎岖不平,就连性能最好的汽车在上面行驶也会颠簸不断。这种情况在非洲国家屡见不鲜。阿瓦萨本身是一个商业中心,但经营的多是当地自产自销的初级农产品。风景如画的东非大裂谷湖泊是其主要景点及水源地。阿瓦萨与外界几乎隔绝,但其政治和种族动荡并非不为外界所知。暴力事件在过去30年里时有发生,比如,在2002年一场反对地区独立的抗议活动中就有100多人丧生。

在某种程度上,阿瓦萨至今还留有农村印记。装载着农产品的驴车在大街小巷仍然最为常见。但在某些重要层面,阿瓦萨不再是与世隔绝的闭塞地区,而是一个蓬勃发展的工业中心。在城外几公里远的地方,一座建筑场地蓦然可见,如今已成为主要景点,那里就是哈瓦萨工业园,有十几家制造纺织品、服装和其他工业产品的跨国公司坐落于此。每天都有数千名工人往返于这个工业园工作。他们用机器为西方服装品牌制作各种各样的短裤、衬衣和毛衣,生产各类长卷纺织品。而且,出人意料的是,它还为埃塞俄比亚本地市场制作和包装纸尿裤,因为埃塞俄比亚正在经历一波持续的婴儿潮。

去往阿瓦萨也不再是一个难题。有一条新修的马路直通工业园,不久之后还会新修一条多车道公路,连接阿瓦萨与亚的斯亚贝巴以及更远的地方。一座先进的小型支线机场正在建设中,将取代当前用来接待抵达旅客的简陋危房。埃塞俄比亚铁路公司正在运营的一条铁路线,可以直接连通阿瓦萨、首都亚的斯亚贝巴的郊区与邻国吉布提,这是埃塞俄比亚通往东部海洋的通道。所有这些新项目都能助推哈瓦萨工业园打入国内市场、非洲大陆市场乃至全球市场,从而为上万名当地工人带来更多的就业和发展机会。而且,这些投资已见成效。据埃塞俄比亚投资委员会宣布,在2019财年,哈瓦萨工业园和其他几个工业园创下了1.4亿美元的出口纪录,为7万余人提供了就业岗位。这是一个非常瞩目的成功案例。哈瓦萨工业园自启用至今不过三年时间,其他几个工业园的运营时间更短。

对于在那里生活、工作的埃塞俄比亚人而言,工业园改变了他们的命运。一个典型的例子是工业园内宏远(Everest)服饰公司的当地总经理塞纳特·索尔萨。越来越多的埃塞俄比亚人从农村到城市发展,索尔萨正是其中一员。她到阿瓦萨读大学,获得会计学位后,成为一名独立会计师。此后的10多年里,她一直为该地区的一些小公司提供会计服务,积累了大量工作经验。后来,亚洲服装公司宏远服饰入驻工业园,并且要招聘一名当地经理,于是索尔萨果断地抓住了机会。她会说英语,能和中国总经理交流,以前为小公司工作时还积累了一些管理经验。而且,作为一名本地人,她本来就对当地工人比较熟悉。雇用她对宏远服饰公司来说是一个双赢之举:一方面,公司招到了一名文化程度高、具有金融专业知识的经理;另一方面,索尔萨也有机会在跨国公司工作,并在职业上取得进一步发展。

阿瓦萨的工业化对许多当地劳动者来说都是一件好事。宏远服饰在哈瓦萨工业园雇用了2300名工人,其中绝大部分人来自阿瓦萨或周边地区,大约95%的员工都是女性(索尔萨立即指出,她们的最低年龄限制是18岁)。“她们中的多数人以前都没有工作,或者在家庭作坊里干活。”索尔萨说,“她们通常接受过中小学教育,但很多人没能高中毕业。不过做一名加工服装的工人,这些不成问题。”这些工人经过最多为期3个月的上岗培训后,很快就能和世界各地的工人竞争。走在工厂里,你可以看到这样的工作机制:有的生产线在高速运转,有的稍微慢点儿。在每条生产线的末端都有一个记分牌,显示每组工人已经制作的特定服装数量,并与前几周的成果做比较,以示进展情况。午餐时间,工人们聚集在一个单独的房间内就餐。下午5点,会有大巴车将他们载回阿瓦萨市中心。这项工作并不容易,也不会让人特别有成就感,但与大多数人以往所习惯的生活相比仍然存在巨大的变化。这份工作能带来更稳定的收入,能让人们有机会离开影子经济而在实体经济中工作,能带来虽然少但切实的个人发展机会。这些都是工业化在起作用。这是世界各国从农村向城市、从农业社会向工业社会发展的普遍模式。这一过程充满了试错、困难和权衡,但直至今日,这仍是世界上已知的最成功的发展模式。

埃塞俄比亚及其国民已经从工业化政策中获得了回报。过去15年里,埃塞俄比亚的GDP增速平均每年高达10%,其GDP在2003年还不足150亿美元,到2018年已飙升至600多亿美元。就经济增长率而言,埃塞俄比亚堪称“新兴市场”中的闪耀明星,中国达到这么高的增长率是在21世纪初。鉴于大多数埃塞俄比亚国民在千禧年之交时仍然在贫困线上挣扎,经济的高速发展对于他们而言无疑是一道福音。该国的人均GDP几乎增长了两倍,以“不变”美元来衡量,国民人均日收入从2003年的勉强超过50美分攀升至如今的接近2美元。这一飞跃从实际价值来看可能微不足道,但从所谓的购买力平价角度来看,埃塞俄比亚的普通大众已经摆脱了极度贫困。以购买力来衡量,埃塞俄比亚的人均GDP在2003年经济发展刚起步时还不足500美元,而在2018年已经超过了2000美元。

但是,与其他地方一样,埃塞俄比亚也为经济发展付出了环境代价。埃塞俄比亚的二氧化碳排放量的增长几乎与经济增长同步,在2002—2017年增长了2倍。2017年,埃塞俄比亚的二氧化碳排放量为1300万吨。相对而言,这一数字微乎其微,在360亿吨的全球总排放量中几乎可以忽略不计,但这一趋势不容忽视:随着国家越来越富裕,它所制造的污染越来越多。这并不是说埃塞俄比亚和其他新兴市场没有为绿色发展做出努力,也不是说它们的国民不关心全球变暖。早在2011年,埃塞俄比亚政府就发布了绿色经济战略,旨在通过发展适应气候变化的绿色经济,使该国到2025年成为中等收入国家。该战略一方面是要解决森林砍伐问题,因为在埃塞俄比亚这个问题十分严重。根据联合国发布的数据,“20世纪初,该国的森林覆盖面积占国土总面积的35%,进入21世纪,这一数字已经快要跌破4%了”。依照这一战略,埃塞俄比亚在2019年召集了上百万公民,在一天之内种植了3.5亿棵树苗。埃塞俄比亚政府绿色发展战略的另一个重点是,发展可再生能源和/或清洁能源,以扩大现在所剩无几的能源供应。根据国际能源署(IEA)的报告,埃塞俄比亚“在过去20年里已经取得了巨大的进步”,但至今仍只有一半的人能用上电。自1990年以来,水电、生物燃料、风能和太阳能发电量增加了一倍多,它们共占全国能源总供应量的90%。但化石燃料的能源供应量增加了3倍多,1990年在能源总供应量中的占比还不足5%,到2017年这一占比已经翻了一番。这表明,即使在今天,也没有一种神奇的发展模式能让贫穷落后的国家在进行工业化的同时控制碳足迹。经济的发展、生活水平的提升与碳足迹的扩大,三者始终如影随形。

这是全球应对气候变化的核心难题,而且几乎可以肯定的是,之后情况还会变得更糟,直至出现转机。造成这一结果的,不(仅仅)是市场失灵,也不(仅仅)是企业或政府领导力的缺乏,而是人类的本性和天生的欲望——不仅要生存,而且要发展。因此,对于许多收入不稳定的人来说,在气候因素与更好的生活之间根本别无选择,即使后者会给环境带来更大的破坏。如果你用不上电,没有稳定的收入,甚至餐桌上没有可食之物,那么气候变化根本不会在你所考虑的问题之列——尽管从长远来看,气候变化会威胁人类的生存。

这就解释了很多问题。比如,为什么生活在印度尼西亚雅加达海岸附近的人们,即使面对快速下沉的家园,仍然若无其事地进行着日常活动。为了阻止不断上升的海平面淹没整个社区,那里不得不建起大海堤,那是一堵数米高的混凝土墙。当地有一座清真寺被潮水淹没,从而被废弃,从屋顶俯瞰海堤和被淹没的清真寺,形成了一种相当反乌托邦的景象。

这也解释了法国为何会发生所谓的“黄马甲”运动。2018—2019年,数以千计的抗议者走上街头进行示威抗议,给巴黎等数十个城市造成重创,最终让政府加征燃料税的计划落空。他们的口号是:“月底,世界末日:同样斗争。”(Fin du mois, fin du monde: même combat.)从理论上来说,法国政府提出的加征燃油税计划理应给环境带来积极的影响,因为它将激励法国民众减少私家车的使用,而更多地选择其他交通方式。但在实践中,这会使乡村人口进一步被边缘化,而他们本来就因为得不到城市中的教育、工作和积累财富的机会而愤愤不平。

最后,这还解释了为什么帕劳、瑙鲁、特立尼达和多巴哥等岛国一边遭受着海平面上升、极端天气和气温升高等气候变化之苦,一边又是世界上人均二氧化碳排放量最多的国家。以帕劳为例,这个国家因其发展中国家地位而不在《京都议定书》的约束性减排国家之列。尽管如此,该国仍在2015年承诺到2020年减少30%的能源消耗。该国也是第一批签署《巴黎协定》的国家。但按人均计算,帕劳人仍然是世界上最能制造污染的,因为这个岛国主要靠化石燃料发电。这就是这场应对气候变化之战的核心难题。

“我们还有希望吗?”

在考虑解决措施之前,我们有必要先问一句:“我们还有希望吗?”如果人类从骨子里就如此渴望过上更好的生活,而根据过去200年的发展经验,这意味着每个人的碳足迹都会不断扩大,那么即便有更加可持续的气候政策,它们真的可行吗?

这一问题的答案在一定程度上取决于4个关键的大趋势,这些趋势又在不同程度上取决于整个社会以及其中有影响力的个人。

第一个大趋势是城镇化。据联合国统计,截至20世纪60年代,全世界大约2/3的人口都生活在农村地区。29这些人多数生活在发展中国家,在电力、交通或者其他方面的能源消耗非常受限,其碳足迹也十分有限。但是,一场变革已经开始,并将在未来50年内彻底改变全球格局。截至2007年,世界上有一半的人口居住在城市。今天,城市人口占比已经超过55%并在持续增长。这一趋势在世界各地都十分明显,但以亚洲最甚,尤其是中国和印度。在全球,人口超过2000万的超大型城市中有一半左右都位于这两个国家,而且这些超大型城市大多都是由村庄发展而来。例如,在2020年前鲜为世界关注的武汉,是一座拥有1100万人口的大城市,但1950年的武汉还只是由3个小镇构成,人口加起来也不过100万。

城镇化趋势至今丝毫没有减弱的迹象。联合国称,城镇化将于2050年完成。届时,全世界2/3的人口都将生活在城市或大型城市,仅剩1/3的人口生活在农村地区。

乍一看,这一趋势可能会令关心气候变化的人士感到担忧。一些最新或最发达的城市同时也是人均碳足迹最大的城市,比如多哈、阿布扎比、新加坡和中国的香港。底特律、克利夫兰、匹兹堡或洛杉矶等美国著名城市曾率先提出在城市中“汽车为王”的理念,而基于该理念的城市设计似乎与绿色交通、绿色生活背道而驰。但据挪威环境经济学家丹尼尔·莫兰所说,城市带来了大部分的人口碳排放量,其中隐含着一线重大希望。莫兰告诉美国航空航天局地球观测站:“这意味着,只要少数几个地方的市长和政府采取一致行动,就有望大幅减少全国总的碳足迹。”比如,中国的深圳近年来已经实现城市出租车和公交车全面电动化,这对一个拥有1000多万人口的城市来说意义重大。再比如,新加坡通过征收高额购车附加费、严格实施汽车许可证(即拥车证)数量零增长,大幅减少私车出行,也会带来很大的改观。

第二个大趋势是人口变化。在近代历史上的大部分时间,全球人口的快速增长意味着碳排放量也呈螺旋式上升。实际上,1950—2017年,全球碳排放量呈指数级增长,二氧化碳年排放量从50亿吨增至350亿吨。同一时间,世界人口也呈爆炸式增长,从1950年的25亿增至如今的近80亿。西方国家在20世纪五六十年代出现了婴儿潮,随后发展中国家迎来了一波更大的婴儿潮。在这个人口密度更大的世界,人均GDP的不断增长意味着全球二氧化碳排放量受到双重刺激:一是人们的生活更加依赖能源,二是越来越多的人过上了这种生活。因此,即使人们很早之前就开始减排,仅仅是人口增长这一个因素也会导致全球的碳排放量不断上升。

但这种情况同样存在一线希望。尽管世界人口预计在2050年之前会持续增长,但其增长速度日渐放缓。包括意大利、德国以及俄罗斯在内的欧洲大片地区正在经历本土人口结构的崩溃。例如,2018年俄罗斯总人口出现10年来的首次下降。联合国还预测,到2100年俄罗斯人口将减半。东亚国家的情况十分类似。日本人口的减少已尽人皆知。印度很快会超过中国成为世界上人口最多的国家,但即便如此,印度近几十年的生育率也大幅下降。1960年,印度育龄女性平均每人生育6个孩子,到2019年,这一数字减少到两三个。如果这一趋势继续下去,印度人口在未来的某个时间点也会减少。只有非洲大陆的生育率超过2,这表明其人口仍将增长。尽管预期的全球人口结构崩溃会带来一定的挑战,但它也有助于人类应对气候变化。

第三个大趋势是技术进步。这也是一把双刃剑。首先,正是技术进步引发了环境恶化。在19世纪初以及第一次工业革命全面开展之前,人类对环境的影响虽然深刻但仍可逆转。然而,随着工业化浪潮席卷而来,我们开始快速消耗地球上最珍贵的一些自然资源,先是石油和煤炭等能源,后来还包括稀土矿物,甚至包括氦气等气体。与此同时,人类活动的碳足迹变得比以往更大。正是工业化的发展带来了“人类世”(Anthropocene)的概念,它暗示着人类对地球气候变化和生物多样性的减少负有责任。之后的第二次和第三次工业革命给世界带来了内燃机、汽车、飞机和计算机,提高了几十亿人口的生活质量,但也使人类的环境足迹比以往更大。

最近开始的第四次工业革命给我们带来了新的技术成果,比如物联网、5G、人工智能和加密电子货币。从目前来看,第四次工业革命使人类的环境足迹继续扩大。据科学家计算,获取比特币(一种最流行的加密电子货币)所消耗的电力每年会产生22兆~23兆吨二氧化碳,这相当于约旦或斯里兰卡等国一年的排放量。同时,尽管联网设备使我们的能源基础设施变得智能,但不代表它会自动变得环保。为此,消费者和生产者需要有意识地选择绿色能源供应,且高效利用能源。

尽管如此,若想成功遏制气候变化,我们仍然需要让科学和企业创新发挥出重要作用。电动发动机曾长期不被看好,因为比起使用化石燃料的内燃机,它造价高、性能差,但现在电动发动机的性价比正快速提升。电池技术取得的重大进步,意味着风能、水能以及太阳能的普及利用已近在眼前。只要用途得当,计算机以及其他智能设备不会增大能源和资源的消耗,反而有助于节约能源和资源。

但是,在这方面,我们可采取的最快、最有力的措施是排除能源结构中的煤炭和其他化石燃料。不过我们还没做到这一点。事实上,在新兴市场每年仍会新增几十家煤炭工厂。但情况正在改变。美国和欧洲的大型机构投资者越来越不看好煤炭工厂。它们之所以这么做,可能是出于气候变化活动家和客户的压力,也可能只是出于理性考虑——正如英国央行前行长马克·卡尼曾发出的警示,化石燃料工厂终将成为搁浅资产。比起化石能源技术,清洁能源技术的经济可行性在不断提升,受此影响,印度和中国的企业家及政府也开始采取行动,努力实现低碳未来。在这方面,世界经济论坛也在采取行动。在我们举办2020年达沃斯年会之前,我和国际工商理事会主席布莱恩·莫伊尼汉、首席执行官气候领袖联盟联合主席费卡·西贝斯玛一道,邀请参会者加入“净零挑战”(Net Zero Challenge),承诺到2050年或更早实现温室气体排放“净零”目标。许多企业领导人积极响应。

最后一个大趋势是我们自身,或者说是我们不断改变的社会偏好。这一趋势能放大其他所有的趋势,也能终止其他所有的趋势。在现代社会的大部分时期,人类表现出来的偏好是想要更多、更好、更快。考虑到许多西方民众直到19世纪末生活水平还很低,人们渴望更好的生活、渴望把更多的财富转化为消费实属正常。如前文所述,在很大程度上,这种愿望至今在许多发展中国家仍然盛行,这一点无可厚非。只需要到越南、印度、中国或印度尼西亚的繁华城市去看看,你就能理解人类的永恒愿望——日复一日、年复一年、一代又一代地向前发展。

但如今在所谓的发达国家,社会偏好正在发生系统性改变。很多人意识到能源充足的生活方式有着负面影响,因此开始摒弃以往所追求的习惯和产品。财富开始转化为健康。

例如,据彭博社报道,2019年11月,乘坐飞机在德国城市间往来的人数比前一年同期下降了12%。与此同时,德国联邦铁路公司的乘客数量达到了新的高峰。人们认为,这要归因于“坐飞机可耻”(flight shame)这场应对气候变化的平民运动逐渐为大多数人接受。在其他地方,人们渐渐考虑回归公共交通、自行车,或者干脆步行前往目的地,而摒弃汽车出行。伦敦、马德里、墨西哥城等许多城市正在出台限制汽车出行的政策,这不光是出于缓解交通拥堵的考虑,还是基于居民认知的改变——人们越来越觉得城市应当为人服务,而不是为汽车服务。作家笔下的美国人一度把拥有汽车视为长大成人的标志,可就连在这个体现着典型的汽车文化的国家,千禧一代也越来越倾向于不购车。

所有这些演变早在新冠肺炎疫情到来之前就已开始。之后,城市的强制封锁引发了一场小型的交通革命。世界经济论坛城市交通专家桑德拉·卡巴莱罗和城市雷达公司(Urban Radar)的CEO菲利普·拉平在疫情期间写道:“新冠肺炎疫情期间城市实施封锁后,道路被清空,交通运输机构要么完全停止运营,要么大幅减少服务,行人和骑行者得以重回街道和人行道。”从奥克兰到波哥大,从悉尼到巴黎,甚至在我们所居住的城市瑞士日内瓦,都新修了许多自行车道,使人们可以选择更环保和更有益于公众健康的通勤方式。在新冠肺炎疫情期间,欧洲也加速推进火车的回归,还计划在相距较远的城市,比如西班牙巴塞罗那与荷兰阿姆斯特丹之间开通新的卧铺列车。2020年秋,德国交通部部长安德烈亚斯·朔伊尔甚至向其欧洲同僚提议,鉴于以前的“全欧快车”(Trans Europe Express)网络已经无法在国际客运中发挥积极作用,有必要搭建新的“环欧特快”网络取而代之。

显而易见,这些习惯之所以正在发生改变,是因为西方民众越来越意识到,应对气候变化不光是结构性问题,也是个人问题。年青一代更是从投资、学业、出行等各方面付诸行动,其中千禧一代和Z世代表现得尤为突出。他们的投资对象越来越限定于符合ESG45标准的企业,这些企业为“净零”活动做出了具体承诺。他们会购买环境破坏性更小的产品和服务,学习有助于解决气候变化问题的专业,从事不会加重环境问题的工作。这种态度上的转变对社会各阶层都在产生影响。例如,微软承诺抵消其当前、未来乃至以往的二氧化碳排放量。软件服务提供商Salesforce的联合首席执行官、世界经济论坛董事会成员马克·贝尼奥夫在2020年达沃斯年会上宣称,“我们所熟知的资本主义已死”,建议企业坚持利益相关者模式和更好的生态管理。全球著名资产管理公司贝莱德集团的CEO拉里·芬克告诉各位企业领导者和客户,“每个政府、企业和股东都必须直面气候变化问题”,还称自己的公司正在“从其积极管理的投资组合中剔除一些公司的股票和债券,只因这些公司从动力煤生产中获得的收入占比超过 25%”。

在世界经济论坛,我们也看到了这种态度的转变,并且也在积极行动。我们的活动正变得越来越环保。比如,我们采取了激励措施,以鼓励参会者乘火车而不是乘飞机前来,并且承诺抵消碳排放;我们还选用可回收材料,在当地采购食品和饮料。我们之所以做出这些努力,主要是因为我们有着坚定的信念,而且有着保持言行一致的决心,但同时也受到由年青一代主导的社会偏好改变的驱动。我们所做的努力表明了一点,一旦发生气候危机,任何政府、企业或组织都无法做到不受影响。

归根结底,我们应该从这四大趋势中看到希望:气候危机还是可以化解的,生物多样性下降、自然资源减少、各类污染严重等相关的地球危机还有机会扭转。以迫在眉睫的气候变化问题为例,减缓气候变化的速度已经是一个巨大的挑战,不仅需要各国政府通力协作,还需要这个星球上所有的利益相关者共同努力才能应对,更不用说终止气候变化了。我们不能仅依赖某一个利益相关者群体。历经多次推迟和辩论后,170多个国家政府终于达成共识,在《巴黎协定》中定下一个共同目标:将全球气候变暖幅度控制在1.5℃以内。但各国政府迟迟不肯实施各自的气候应对方案——甚至可能根本没有方案。一个原因在于,尽管气候变化问题紧迫,但它仍不是选民的当务之急。另一个原因在于,各国政府并不具备独自行动所需的全部知识或能力。于是,这时候就要看其他利益相关者——企业、投资者、个人以及整个公民社会将如何行动。

从理论上看,我们和他们的核心任务都很简单,那就是尽可能快且尽可能多地减少二氧化碳、甲烷等温室气体的排放。有句谚语是“跟着钱走”,用在气候问题上就是“跟着排放走”。这样一来,我们自然而然就会找到最大的排放源——能源生产。因此,各利益相关者都应当把减排重点放在这方面——用可再生能源替代化石��料,当前的一些超标排放就会自然停止。如果投资者不再投资煤矿工厂,企业和消费者转而使用可再生能源,制造商和其他企业也采取同样的做法,那么就能直接避免数十亿吨二氧化碳的排放。这是每一位利益相关者能做出的最直接也最重要的贡献。

当然,实践的过程会存在许多障碍。如前文所述,短期来看,煤炭、石油和天然气仍比其他能源更廉价。许多发展中国家仍依赖化石燃料,因为这是通往发达国家和工业化的成本最低的路径,就连工业化经济体也很难完全摒弃化石燃料。比如,在美国仍然有新的化石燃料工厂和基建项目在酝酿之中或正在执行。这些国家的企业和公民不得不游走在政府政策之外,有时甚至会违背政策。此外,在许多石油及天然气生产大国,人们在某种程度上已经对石油和天然气提供的廉价能源依赖成瘾。

在减少温室气体排放方面,除了改变能源生产的来源外,第二个主要方法是在世界范围内实施碳定价和“总量管制与交易”制度。通过对排放量定价,或者通过对行业或企业的总排放量及其在市场上可交易的排放额设定上限,单个行为主体就会出于成本考虑而减少碳排放。事实上,当排放的经济成本升高时,以更节能的方式生产、出行或从事其他经济活动将变得更加有利可图。

这并非仅仅是纸上谈兵。欧盟从2005年就开始实行“欧盟碳排放交易体系”(EU ETS)。根据欧盟提供的数据,被限制排放的包括11000多个耗能严重的设施(发电站和工业工厂),以及往返于欧盟国家间的各个航班,被限制的排放量占“欧盟温室气体排放量的45%左右”。据美国国家科学院的研究人员所言,这一制度取得了一定的成效,2008—2016年,该制度累计减少二氧化碳排放量近12亿吨,约占总排放量的3.8%。欧洲的“总量管制与交易”制度是同类制度中规模最大的,但并非绝无仅有。澳大利亚、韩国等国家,以及加利福尼亚州、魁北克省等地,都设有类似的制度。许多其他地方还引入了更加直截了当的碳价格或碳税制度。

碳定价和“总量管制与交易”机制直接作用于排放温室气体最多的主体——能源生产商和大型工业企业,有助于改善能源结构、提高能源效率,是最有力的两大减排举措。但事实上,个体、开明企业和公民社会团体也可以有所作为,即使这意味着他们有时候不得不逆流而上。在世界经济论坛,有一群首席执行官气候领袖多年来一直致力于使其企业采取影响更加深远的自愿行动。他们之所以这么做,是因为他们明白在短期内搭便车毫无意义,一旦到达终点,所有人都将失败。那么,他们如何能够发挥积极作用呢?我们与波士顿咨询公司开展的一项研究表明,他们应围绕三个方面采取行动。

1. 降低排放强度。往往可以通过提高能源利用效率,减少自身经营和供应链活动中的温室气体排放。

2. 调整投资重点。只投资那些能源清洁型企业,并通过实施内部碳价格,揭示某些业务的真实成本。

3. 创新经营模式。通过改革现有模式,寻求绿色发展新机遇。

在这方面,全球集装箱航运巨头马士基集团是绝佳范例,我们会在第九章进行更加深入的案例分析。在企业运营中的温室气体排放强度方面,马士基集团正在试验更加节能的食物冷藏方式,并投入使用少依赖化石燃料、多借助风能的轮船。在投资组合方面,马士基集团将石油业务剥离,转而专注于核心的航运业务。此外,马士基集团还在探索一种新的经营模式,希望把货物运输从“港到港”转变为“门到门”,从而扩大业务范围。这让马士基集团得以在减少运输总排放量的同时,实现持续不断的发展。马士基集团在化石燃料的生产、分销和消耗方面都非常活跃,如果这样的企业都能实现绿色转型,那么绝大多数其他企业也能转型成功。

……

但我们必须意识到,时不我待。有害气体在大气中的累积,就像往只有一个小排水口的浴缸里注水。到某个点时,浴缸即将注满,这时候再缓缓地拧紧水龙头已经来不及了。除非确保再也没有水注入,否则浴缸里的水就会溢出。气候变化也是如此。事实上,世界已经十分接近一个临界点,一旦真的到达这个临界点,即便人们采取极端的措施也无法阻止局势失控。从某种意义上说,2020年出现的唯一的积极迹象是,世界到达临界点的时间被延迟了,因为许多地方连续数月的排放量几乎零增长。未来即便经济充分恢复运转,努力迈向更加美好的后疫情时代的我们,仍需要像这样控制住排放量。

0 notes

Text

Which country will host the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) of Parties (COP-25) meeting on 2 – 13 December 2019?

Which country will host the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) of Parties (COP-25) meeting on 2 – 13 December 2019?

Which country will host the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) of Parties (COP-25) meeting on 2 – 13 December 2019?

A. Geneva, Switzerland

B. Moscow, Russia

C. Santiago, Chile

D. Paris, France

(more…)

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

World getting hotter, more dangerous faster than thought: UN chief - world news

The world is getting hotter and more dangerous faster than previously thought, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said here at the COP 25 climate conference on Wednesday, urging the countries that carbon pollution must stop rising in 2020 to keep the Paris Agreement goals within realistic reach.The Paris agreement was adopted by 195 parties at the UN climate conference “COP 21” held in the French capital in 2015 with an aim to reduce the hazardous greenhouse gas emissions.Nineteen members of the G20, except the US, have voiced their commitment to the full implementation of the deal.“The world is getting hotter and more dangerous faster than we ever thought possible. Irreversible tipping points are within sight and hurtling towards us,” he said while addressing a high-level meeting at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) COP25 in the Spanish capital.“It is a testament to the urgency of the job before us all. The scientific evidence presented in recent weeks has only heightened this urgency,” he said.On December 2, Guterres opened the COP 25 climate summit here, warning that the governments risked sleepwalking “past a point of no return” if they remained idle.The annual negotiations to bolster the 2015 Paris Agreement to curb global warming began in the backdrop of unusually severe climate related disasters this year, from fires in the Arctic, Amazon and Australia to intense tropical hurricanes.In his latest address, Guterres urged the countries that carbon pollution must stop rising in 2020 and start falling to keep the Paris Agreement goals within realistic reach.“We are a very long way behind, but there is still reason to believe we can win this race,” he said.However, he noted that the world has the force of science, new models of cooperation, and a rising tide of momentum for change.“Crucially, we have a global framework in the Paris Agreement to get the job done. We now need to put it fully to work,” he said.He also emphasised that the countries must honour the pledges made in Paris in 2015 to scale up their national climate pledges every five years, starting in 2020.Noting that the next 12 months will be crucial for climate action, he said that in 2020, the world must deliver what the scientific community has defined as a must, else it will pay an “unbearable price.” “That means embarking on the path to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 45 per cent from 2010 levels by 2030 and to achieve net zero CO2 emissions by 2050,” the UN chief said.He noted that this is what the UN expects from the review of national commitments under the Paris Agreement at COP26 next year in Glasgow, UK.“And I hope as many countries as possible will step up this year at COP25,” he said.Guterres also said that lifting ambition over the next 12 months has been the touchstone of this year’s COP.“And it was a centrepiece of the Climate Action Summit I convened in September,” he said.Noting that the world is still a long way from its objective of becoming carbon neutral by 2050, he hoped that “we can limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius.” “We need more ambition, more solidarity and more urgency, he added. PTI SAR PMS PMS

Read the full article

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Age: 14 years old - Born on November 25th 2004 Name: David Henry Francis Wicker Family: 1 older sister who is studying in Germany Studies: Second year of High School - Advanced Sciences oriented High School Articles on Me: https://docs.google.com/document/d/17cEYGScDibzUB6JtDHBvewsLQrWsJMCgtKDsmmoowoo/edit?usp=sharing MY STORY I started school striking at the beginning of January 2019. It was a crazy thing, and it was perceived under different views by people and by my own teachers. Why did I start school striking? Because I felt suffocated. Before I started to get informed, I was aware of something teachers called “Global Warming”, which was described in 1 page of my geography book. But it was described as a solved issue. The way people talked about climate change, it seemed as everything was already “solved” and that the institutions and governments of the world were taking care of it. THE BEGINNING After watching Greta’s speech at the United Nations, I read the IPCC report on the 1.5°C and watched documentaries of David Attenburough and did a small online course on edx on global heating. I had come to learn what was actually happening with our climate. I felt as my own rights were being infringed, and I had no way to release this anger out of me. But fortunately, I do have the possibility to express my opinion. I consider myself a privileged kid, and it would be an insult to those who do not have the same possibilities I have, not to fight for climate justice. And it turns out, the best way to attract attention for us schoolchildren, is to actually “skip” school. So I did it. I joined a group of older students (two girls from university) and together we formed the first “Fridays For Future Torino” chat. On the first Friday of January, we struck. We went into the center of Turin and we just sat in the middle of a plaza with a couple of signs. Some people started taking pictures of us, I remember. We didn’t think of this school strike as something that was going to last long, I personally didn't think we would ever be able to bring any change. But as the weekly strikes continued, the people who joined us were more and more. One friday, we reached over 300 strikers with us. We were indeed slowly bringing a change. In the middle of January, I also got in contact with other activists all over italy, and we formed the “Fridays For Future Italia” group. At the same time, I got in contact with activists from Sweden and other countries, and together we formed the international level of Fridays For Future. Known activists I work with often: Luisa Neubauer from Germany, Anuna De Wever from Belgium, Lily Platt from the Netherlands, Alexandria Villasenor from the USA, Greta Thumberg from Sweden, and many many more activists from many countries! EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT + FIRST GLOBAL STRIKE On the 13th of March I was invited to the European Parliament, along other 59 activists from 20 different european countries. We were invited to attend the climate debate at the parliament and to have a press release shortly after. I was stunned to see with my own eyes how the debate in the european Parliament went: It lasted only 45 minutes, because they had to talk about Brexit. Only 45 minutes dedicated to the most urgent problem of our time, in order to leave more time to other smaller and - to this perspective - insignificant issues. So we organized the first “Global Strike For Future”, the first strike/demonstration with a global extension. People all over the world, fighting for the same cause. We were able to bring to the streets of Italy over 475.000 people. Over 30.000 people in Turin. We, as organizers of these strikes, couldn't believe what we had achieved. Little did we know, THAT was only the beginning. INVITE TO THE SENATE In April, a huge news reached all italian newspapers: Greta Thunberg was going to come to Italy. The Italian Senate of the Republic invited me to the Senate as representative of the italian Fridays For Future movement, and together with Greta Thunberg we went into the Senate. She held a speech in front of the committee, while I gave some interviews to the italian press. It was the first time I met Greta SECOND GLOBAL STRIKE + EU PARLIAMENT OCCUPATION On the 24th of May we held the Second Global Strike For Climate. Our numbers doubled globally. We had captured the attention of media outlets all over the world. On the 24th of May, I had travelled to Brussels for the international demonstration that happened there, as the “delegate” activist from the italian movement. After the demonstrations, we thought to bring it a step further. It was the day before the European Elections, and we had to capture all the attention we could and raise awareness about the climate emergency as much as we could. So we Occupied the European Parliament, and I was the youngest activist there. My parents were still in Italy - they don’t accompany me when I travel for activism, so I travel alone across Europe. It is itself a really long story to tell, so I will not go into details, but I will mention that after the occupation, which lasted 25 hours straight, day and night, we were able to make the delegate of the parliament come down to talk to us, and we gave him a statement from our movement. SMILE MEETING While everyone in Europe was on vacation, we organized our second International meeting, to find common ground, values and goals as a global movement. I was part of the italian delegation for the meeting, and I was in the ending press conference of the meeting. THIRD GLOBAL STRIKE In the week between the 20th and 27th of September, we held the biggest mobilisation that the climate movement had ever seen. Over 8 million people joined the demonstrations worldwide. In My city where I organized the strike in, we brought to the streets over 150.000 people! All of Italy counted over 1.1 million strikers! It was a huge success, which gave us a lot of visibility. In my city we were able to make a motion and get it voted to Declare Climate and Environmental Emergency - this motion passed! Now the local institutions have to give us a report every 2 months, detailing everything the city has done to lower emissions. But even the Third Global Strike was not the end of the movement. We are already organizing a net one, which will happen on the 29th of November worldwide. The aim of this next global strike is to put pressure on the COP 25 in Madrid- Conference of Parties - organized by the UNFCCC. MORE ON Other than the weekly strikes and Global Mobilisations, we organize lots of activities to bring attention to different aspects of the climate emergency. Just 2 weeks ago, I organized a meeting with the Town Mayor and the University of Turin, to bring voices to the indigenous leaders of the Amazon Rainforest, who are getting killed by people wanting to gain more land to plant Soil, in order to grow RED MEAT production. People whose territories are getting destroyed by the meat Industry. After having joined the movement, a lot has changed in my own life. I no longer have “free afternoons”. I spend all my time organizing, doing international conferences and coordination meetings. Due to different time-zones, I often go to sleep at 4:00 in the morning, and in order to follow up on my school work I often do not sleep at all. It is a sacrifice I am willing to make. Also I have implemented some good habits: I no longer use plastic bottles, nor straws and I try to buy food with as least plastics as possible - unfortunately in italy everything is wrapped in layers and layers of plastics, so this is very hard - I no longer take planes and I am pushing my parents so they do the same. Whenever I have to travel, I make sure to use public transport and to take trains or busses instead of planes, even if it means travelling 10 hours in a bus, I am willing to do it - and I have already done it more than once. Some articles on me: https://docs.google.com/document/d/17cEYGScDibzUB6JtDHBvewsLQrWsJMCgtKDsmmoowoo/edit?usp=sharing

0 notes

Text

Cabinet approves negotiating stand of India at COP 25 to UNFCCC

Cabinet approves negotiating stand of #India at #COP25 #ClimateSamurai #UNFCCC #Climate

The Union Cabinet chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Wednesday approved the negotiating stand of India at the forthcoming 25th Conference of Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) announced earlier this month that the meeting known as the 25th Conference of Parties (CoP) will be held…

View On WordPress

#Climate#climate action#climate agreement#climate change#climate news#Conference of Parties#UNFCCC#UNFCCC COP 25#United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

0 notes

Text

Nigerian Delegates Attend Abu Dhabi UN Climate Meeting

Nigeria is among 1,000 delegates from 150 countries participating at the ongoing United Arab Emirates’ Ministry of Climate Change and Environment High-level Climate meeting to discuss emerging political issues on climate change.

Mr Seyifunmi Adebote, the Leader of Nigeria’s Youth Delegate to the meeting made this known in a statement on Sunday, that the event was holding at the Presidential Palace in Abu Dhabi from June 30 to July 1.

Adebote said the meeting was structured to evaluate and strengthen the initiatives, commitments, and achievements that would be announced at the UN Climate Summit in September.

He said that the meeting was also discussing key and emerging political barriers and opportunities for global climate action.

“The UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, who is expected to open the meeting, has remained deeply concerned about the need for world leaders to come up with concrete and realistic plans to enhance their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by 2020.

“It is expected that the Abu Dhabi Climate Meeting will be the global milestone for the United Nations’ Climate Action Summit which will hold in New York, U. S. on Sept. 23.

“Nigeria, being a member country of Youth Engagement and Public Mobilisation, one of the Summit’s nine transformational areas has shown its commitment towards mobilising people to take action on climate change and ensure that young people are integrated and represented. ”

Adebote said that at a youth pre-event briefing, Esther Agbarakwe of the UN Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth welcomed the Nigerian delegates.

Quoting Samira Ibrahim, one of the Nigerian delegates at the youth pre-event briefing as saying, “this event is very important for Nigeria, we are not here to just talk.

“Our job is to show leaders that the ideas and initiatives of young people around the world are driving landmark Climate Actions.

“We want leaders to know the work that is being done, share feedbacks and make stronger commitments that will scale these Climate Actions.”

Adebote, who is also the State Coordinator, International Climate Change Development Initiative, said Nigeria’s delegation to the Climate Meeting was led by Prof. Adeshola Adepoju, the Director-General, Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria.

He said also representing Nigeria at the meeting was Samuel Makwe, First Secretary of the Permanent Mission of Nigeria to the UN; Samira Ibrahim, a climate specialist from the Department of Climate Change.

Adebote said Amina Mohammed, UN’s Deputy Secretary-General; Patricia Espinosa, UNFCCC Executive Secretary; Carolina Schmidt, COP 25 President were expected at the meeting.

Others include Jayathma Wickramanayake, UN Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth, Achim Steiner, UNDP Administrator and over 500 members of the Emirates.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Rumbling in Robes Round 2 – Civil Court Orders Dutch State to Accelerate Climate Change Mitigation

By Kai P Purnhagen, Josephine van Zeben, Hanna Schebesta, and Robbert Biesbroek

On 9 October 2018, the Civil Division of the The Hague Court of Appeal in the Netherlands has delivered its judgment on the appeal of the ‘Urgenda case’ The Court imposed an order to act on the Dutch government to adjust its policy from 20% to achieve a 25% emission reduction by 2020, compared to 1990 levels (paras 51 and 75). The judgment confirmed the initial ruling in favour of Urgenda in 2015.[i] The consequences for Dutch climate, energy and environmental policy and potentially for climate mitigation efforts worldwide are potentially far-reaching, regardless of possible further appeals by the Dutch government. This ruling raises important questions with respect to the interpretation of Dutch and European Union law, their interrelationship, and possible transferability to other national jurisdictions. In this Commentary, we discuss these issues in turn, starting with a brief synthesis of the judgment.

Summary of the Judgment

The judgment concerned the question whether Dutch law requires the Dutch State to design its climate policy in a way that conforms to international obligations and climate science. Whether such an obligation exists depends on the definition of the State’s “duty of care”. In 2015, The Court in the first instance stated that, when interpreting the State’s duty of care under Dutch tort law, the government’s international obligations need to be taken into account.[ii] These include the ‘no harm’ principle of international law and measures taken with the European Union. In this judgment, the Court stipulated that such a “duty of care” can also result directly from Articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), rather than from the interpretation of the civil law provisions. Articles 2 and 8 ECHR respectively protect the right to life and the right to private life, family life, home and correspondence. These articles cover environment-related situations and place both positive and negative obligations on governments to protect parties’ interests.

In determining the State’s emission reduction targets, the Court further relied on information provided by inter alia the IPCC and other scientific reports, the international consensus reflected in the outcome of the UNFCCC COPs, and national policy documents. All these documents, according to the Court, confirm ‘the fact that at least a 25-40% reduction of CO2 emissions as of 2020 is required to prevent dangerous climate change’ (para 51). Though not legally binding in themselves, the combined reading of these documents resulted in the Courts decision to set this as the State’s duty of care (see inter alia paras 45, 73-74).

Assessment

In our assessment of this case, we focus on three aspects relevant for future climate change litigation cases: 1) the use of climate science as a legal argument in the case; 2) the case’s impact on EU law, and 3) the transferability of the case to other jurisdictions.

1) The Use of Climate Science

Interestingly, the climate facts relevant to the case were not contested between the parties. This allowed the Court to use the climate science submitted and agreed between the two parties in their pleadings, in three ways: First, to define the legal limits of the State’s ‘wide margin of appreciation’ under Articles 2 and 8 ECHR in choosing its measures to prevent climate change. This means the Court concludes that based on references to evidence submitted to the court that ‘it is appropriate to speak of a real threat of dangerous climate change, resulting in the serious risk that the current generation of citizens will be confronted with loss of life and/or a disruption of family life’ (para 45). However, the Court’s legal basis for the inclusion of climate science is unclear. Some of the Court’s reasoning (para 43) suggests that the precautionary principle could act as a legal basis here, a principle that is also part of the ECHR’s jurisprudence in Tătar v. Romania. But this would require the State to take effective and proportionate measures, which is not the standard applied by the Dutch Court (para 42).

Second, the Court uses climate science to define the legal limits of the government’s possibility to determine their emission reduction policy. The Court states that ‘the State failed to give reasons why a reduction of only 20% by 2020 (…) should currently be regarded as credible’ (para 52). Such reasons could have been substantiated ‘based on climate science’. Put differently, the Court limits the Dutch’s government’s political discretion in determining its climate policy by subjecting it to a credibility test, which requires the State to justify its policy at the hand of climate science. Also here, the Court fails to outline any legal basis for this claim, including any reference to the Paris Agreement.

Third, and finally, the Court uses climate science to determine whether an order based on Dutch law to 25% reduction by 2020 would violate EU climate law and policy. It stipulates that ‘the EU deems a greater reduction in 2020 necessary from a climate science point of view’ (para 72). Hence, the agreed upon EU-wide reduction target of 20% by 2020 could not be used as a defence by the Dutch State (Effort Sharing Decision 406/2009/EC). This reasoning leads the Dutch Court to overrule a binding political consensus reached at EU level based on climate science, again without references to any legal basis. One could claim that under the EU principles of precautionary or preventive action, new scientific evidence such as the IPCC’s recent Special Report on 1.5 degrees can cause EU legal obligations to be re-evaluated. However, such a re-evaluation would be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU).

In sum, the careless legal reasoning regarding the applicable legal basis for the inclusion of arguments from climate science weaken the generally welcomed approach towards more scientification of legal reasoning in climate law suits.

2) EU Dimension

The Dutch ruling raises several questions, all of which relate directly to the validity of EU law. The legal chain of consequences goes as follows: the Dutch reduction goals are based on the EU’s Effort Sharing Decision and the EU ETS Directive; these goals are considered to be insufficient to discharge the standard of care of the Dutch government under Articles 2 and 8 ECHR; this implies that the Decision and Directive themselves leave the European institutions in violation of fundamental rights of the ECHR, assuming that a violation of the ECHR creates a basis of invalidity of the EU acts.[iii] The Courts’ interpretations of the relevant climate science, specifically its use of this science in establishing a standard of care, relates directly to the principles of precaution and prevention. These two principles are binding on the European legislature in the area of EU environmental policy.[iv] Clear violation or contravention of these principles would be another basis for invalidity.

Moreover, environmental policy is an area of shared competence between the EU and its Member States, where action taken by the EU pre-empts further regulation by the Member States.[v] Within this area, the Treaties earmark climate change as one of the objectives that the EU should pursue.[vi] This combination of competence and objectives means that the Member States’ obligations under the UNFCCC and any related Protocols and Agreements, such as the Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement, tend to be redistributed within the EU and translated into EU legislation. This means that these obligations are not only binding under international law, but that their restatement also results in binding commitments under EU law. This is considered an important strength of the EU Member States’ international commitments: EU law is far more enforceable than international law, leading to the expectation of a higher level of compliance by EU member states.

The emission reduction targets scrutinized by the Dutch courts are the direct result of EU legislation, which redistribute the Member States’ international obligations. They can be traced back to the EU Effort Sharing Decision, which also serves as the basis for the reduction targets of the EU ETS. As the Court rightly states, Member States are empowered to take more ambitious environmental measures in areas where the EU has legislated. Therefore, in theory, the Netherlands could have maintained its 25% reduction target instead of adhering to the EU’s 20% target.[vii] However, these measures need to be notified to the Commission and cannot create barriers to the internal market.[viii] There is a clear risk that national laws aiming at more stringent emission reductions would impact on the EU’s internal market, for instance through raising vehicle emission standards. Moreover, there would be a tangible effect on the EU ETS, even if not in the ways that the Dutch State argued (para 54-55).

However, the State’s objections based on its obligations towards the EU, and the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), were given short shrift (para 54-58). In fact, the Dutch Court does not address any of these questions of EU law, which may be explained by the fact that the CJEU has exclusive jurisdiction over matters of validity of EU law and a preliminary reference to the CJEU would therefore have become necessary. Not engaging with these questions misrepresents the relative division of political and legal power between the EU and the Member States on this issue. It fails to acknowledge that meaningful change to the Dutch, and EU goals, necessitates a EU level challenge.

3) Transferability

The potential effect of the Urgenda judgment on climate change will not depend on its ability to increase Dutch emission reduction targets to 25% by 2020 compared to 1990; the Dutch emissions are simply not impactful enough to make a meaningful difference globally. Instead, environmentalists hope that Urgenda will pave the way for similar judgments across the world, forcing governments into ambitious climate change mitigation policies and tangible actions. The Court’s focus on the ECHR and the EU Treaties, and its omission of the Paris Agreement as explicit legal basis, limits the application of the case beyond a small group of countries for now.

There are at least three issues that limit the transferability of the Urgenda case: first, under Dutch law, the criteria that determine the right to bring a claim to court make it possible for many types of actors to bring a case. For example, whereas most countries, including Turkey, United Kingdom, and Germany, do not allow ‘public interest actions’ to claim rights under the ECHR, the Dutch court now clarified that under Dutch procedural law this is possible (para 36). Standing has been an important barrier for climate cases and this will continue to be true, unless there are changes to national rules of procedure across the world.

Second, the reliance of the Court on the ECHR would seem like a hopeful sign with respect to cases against other signatories to the ECHR. However, the Dutch Court’s interpretation of the duty of care and margin of appreciation of the Dutch government under Articles 2 and 8, particularly its reliance on climate science, does not bind other ECHR parties. In fact, many countries, like the United Kingdom and Germany, do not even consider the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights binding, only advisory. The use of the ECHR by the Dutch Court is therefore persuasive at most. Similarly, the confirmation of the possibility to impose a duty of care, even if stemming from the ECHR, on the government under tort law is not something that is possible in every jurisdiction. The United States’ government, for example, is explicitly shielded from tort claims.

Third, notwithstanding the Court’s decision, the legal and political reality is that the Netherlands is an EU Member State, which determines its climate policy. In order for any actions taken by the Dutch government as a result of the ruling not to violate EU law, they cannot create unjustified barriers to the EU’s internal market. The European institutions, including if necessary the Court of Justice of the EU, are the relevant institutions to decide this, not the Dutch courts. Moreover, the Dutch judgment calls into question the legitimacy of the EU’s climate aims – 20% by 2020 compared to 1990, and 16% specifically for the Netherlands – in light of the climate science used by the Court (see section 1 above). As mentioned, the validity of EU law can only be assessed by the CJEU, which suggests a strong case could be made for a preliminary reference by the Dutch courts to the CJEU. If the deciding court is the Dutch court of last instance, such as the Hoge Raad which decides on the appeal of the current judgment, a strong case could be made for rendering an obligation to submit a preliminary reference to the CJEU. Such a ruling by the CJEU would also greatly widen the impact of the Urgenda litigation as it would extend its effect to all the EU Member States. It remains to be seen whether this will happen in case of a possible appeal.

Regardless of the climate science, international and national goals – not to mention, our actions to achieve these goals – continue to fall short of what is needed. Using every legal avenue – including private law, human rights, and the courts – to fight climate change is a logical and necessary strategy. The challenges this poses for the relationship between the state and the judiciary, the limits of legal doctrine, and the role of climate science in our application of the law, must be faced head-on.

[i] Schebesta, Purnhagen, Dutch government appeals climate law, Nature 526, 506; Josephine van Zeben (2015), “Establishing a Governmental Duty of Care for Climate Change Mitigation: Will Urgenda Turn the Tide?” Transnational Environmental Law, 4, 339-357.

[ii] Marc Loth, “Too big to trail? Lessons from the Urgenda case” Uniform Law Review, Volume 23, Issue 2, 1 June 2018, Pages 336–353; Eleanor Stein & Alex Geert Castermans, “Urgenda v. the State of the Netherlands: The Reflex Effect – Climate Change, Human Rights, and the Expanding Definitions of the Duty of Care”, 13 McGill J. Sust. Dev. L. 303 (2017).

[iii] Since the EU is not a signatory of the ECHR, this violation would not directly undermine the validity of relevant EU law. However, as the interpretation of the EU’s Charter rights are fairly close to that of the ECHR, one could envisage a similar action brought against the EU’s climate goals under Articles 2 and 7 of the Charter for Fundamental Rights (Right to life and Right to private and family life, respectively).

[iv] Article 191(2) TFEU.

[v] See Article 5 TEU, Article 4(2)(e) TFEU and Articles 191-193 TFEU.

[vi] Article 191(1) TFEU, even if the powers of the Member States to enter into international environmental treaties themselves are not, and arguably cannot, be affected.

[vii] Article 193 TFEU.

[viii] E.g. Article 114(5) TFEU.

Rumbling in Robes Round 2 – Civil Court Orders Dutch State to Accelerate Climate Change Mitigation published first on https://immigrationlawyerto.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

UN & Gov Docs: Paris Agreement Roundup

Read The Paris Agreement Text in the six official U.N. Languages:

Arabic

Chinese

English

French

Russian

Spanish

CRS:

Withdrawal from International Agreements: Legal Framework, the Paris Agreement, and the Iran Nuclear Agreement (Feb 9 2017)

Climate Change: Frequently Asked Questions about the 2015 Paris Agreement (Oct 5, 2016)

Paris Agreement: United States, China Move to Become Parties to Climate Change Treaty (Sep 12, 2016)

Climate Change Paris Agreement Opens for Signature (April 25, 2016)

International Climate Change Negotiations: What to Expect in Paris, December 2015 (Nov 27, 2015)

United Nations:

UN Docs: Paris COP21 Information Hub

UN Climate Change Newsroom - Paris Agreement

“COP 21 Paris (30 Nov – 11 Dec) Website

Paris Climate Change Conference Agenda and Documents

The Lima-Paris Action Agenda (COP20)

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment reports

UN & Climate Change

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

COP-25: What are Conference of Parties-25

COP-25: What are Conference of Parties-25

Conference of Parties-25 (COP-25): Under COP-25, a simple analysis is presented of important news / news published daily in leading newspapers like The Hindu, Indian Express, Live Mint, Business Line, Times of India, Business Standard, DNA and PIB. During the preparation of UPSC and other alternative exams, COP-25 is not possible to give 2 to 3 hours to the newspaper. Keeping all these things in…

View On WordPress

#check the role of Conference of Parties (COP) to deal with climate change#Conference of Parties#Conference of Parties-25#Conference of Parties-25 (COP-25)#COP#COP-25#COP-25 Results#How Successful was COP-25?#Significance of COP#The Purpose of COP-25#What are COP-25?#What are COP?#What are UNFCCC and COP?#Why is COP-25 Important?

0 notes

Text

"Guru Gitar Saya Balawan", Gede Putra Bawakan Bali Harmony di Ajang COP 25 UNFCCC Madrid

Juwita Lala "Guru Gitar Saya Balawan", Gede Putra Bawakan Bali Harmony di Ajang COP 25 UNFCCC Madrid Baru Nih Artikel Tentang "Guru Gitar Saya Balawan", Gede Putra Bawakan Bali Harmony di Ajang COP 25 UNFCCC Madrid Pencarian Artikel Tentang Berita "Guru Gitar Saya Balawan", Gede Putra Bawakan Bali Harmony di Ajang COP 25 UNFCCC Madrid Silahkan Cari Dalam Database Kami, Pada Kolom Pencarian Tersedia. Jika Tidak Menemukan Apa Yang Anda Cari, Kemungkinan Artikel Sudah Tidak Dalam Database Kami.

Judul Informasi Artikel :

"Guru Gitar Saya Balawan", Gede Putra Bawakan Bali Harmony di Ajang COP 25 UNFCCC Madrid

Alunan merdu gitar yang dimainkan Gede Putra Witsen (19) asal Bali, di ajang COP 25 UNFCCC atau Konferensi Perubahan Iklim di Kota Madrid

UNIKBACA.COM

0 notes