#William Whewell

Text

Every failure is a step to success.

(William Whewell)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dal 1600 lo scopo della scienza divenne quello di accumulare certezze e procedere verso la verità. Nel 1834 venne dallo studioso William Whewell, il termine "scienziato" e, per la prima volta, si iniziò a riflettere su una chiara distinzione tra sapere filosofico e sapere scientifico che diventerà fondamentale per tutto il positivismo. L'uno può portare alla disquisizione di #argomenti di carattere generale e l'altro alla sperimentazione e alla realizzazione di discipline sempre più specifiche e settoriali

#filosofia#storia della filosofia#filosofi#pillole di filosofia#modernità#filosofia moderna#epoca moderna#Positivismo#Scienza#Scienziato#William Whewell#Whewell

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Every failure is a step to success.

William Whewell

0 notes

Text

CoTE opening quotes

a list of the opening quotes in classroom of the elite:

What is evil?- Whatever springs from weakness.

-F W Nietzsche, The Antichrist

It takes great talent and skill to conceal one's talent and skill.

-La Rochefoucauld, Reflections or Sentences and Moral Maxims

Man is an animal that makes bargains: no other animal does this - no dog exchanges bones with one another.

-Adam Smith, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

We should not be upset that others hide the truth from us, when we hide it so often from ourselves.

-La Rochefoucauld, Reflections or Sentences and Moral Maxims

Hell is other people.

-Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit

There are two kinds of lies; one concerns an accomplished fact, the other concerns a future duty.

-Jean Jacques Rousseau, Emile or on Education

Nothing is as dangerous as an ignorant friend; a wise enemy is to be preferred.

-Jean de La Fontaine, Fables

Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.

-Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, Inferno

Man is condemned to be free.

-Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism and Humanism

Every man has in himself the most dangerous traitor of all.

-Kierkegaard, Works of Love

What people commonly call fate is their own stupidity.

-Schopenhauer, Philosophical Writings

Genius lives only one story above madness.

-Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena

Remember to keep a clear head in difficult times.

-Horace, Odes (Carmina)

There are two main human sins from which all the others derive: impatience and indolence.

-Franz Kafka, The Zurau Aphorisms

The greatest souls are capable of the greatest vices as well as of the greatest virtues.

-Rene Descartes, Discourse on Method

The material has to be created.

-Florence Nightingale, subsidiary notes (female nursing into military hospitals in peace and war)

Every failure is a step to success.

-William Whewell, Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy in England

Adversity is the first path to truth.

-G G Byron Don Juan

To doubt everything or to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection.

-H Poincare, Science and Hypothesis

The wound is at her heart.

-Vergil, Aeneid

If you make a mistake and do not correct it, this is called a mistake.

-Anonymous, Analects

People, often deceived by an illusive good, desire their own ruin.

-Niccolo Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy

A man who cannot command himself will always be a slave.

-J W V Goethe, Zahme Xenien

Force without wisdom falls of its own weight.

-Horace, Odes (Carmina)

The worst enemy you can meet will always be yourself.

-F W Nietzsche, Thus spoke Zarathustra

lmk if you'd like explanations as to how these epigraphs relate to the story

#classroom of the elite#CoTe#ayanokoji#kiyotaka ayanokouji#quotes#literature quotes#deep quotes#anime#light novel#anime opening

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Somerville, the world's first scientist.

On December 26th 1780 Mathematician and scientist,Mary Somerville was born in Jedburgh.

Before Mary Sommerville came around, the word "scientist" didn't even exist.

When we think of history’s great scientists, names such as Isaac Newton, Galileo Galilei, or Nicolaus Copernicus likely come to mind. The funny thing is that the term “scientist” wasn’t coined until 1834 — well after these men had died — and it was a Scottish woman named Mary Somerville who brought it into being in the first place.

Mary Somerville was an almost entirely self-taught polymath whose areas of study included math, astronomy, and geology – just to name a few. That Somerville had such a constellation of interests, and possessed two X chromosomes, would signal a need to create a new term for someone like her — and scientific historian William Whewell would do precisely that upon reading her treatise, On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences, in 1834.

After reading the 53-year-old Somerville’s work, he wanted to pen a glowing review of it. He encountered a problem, however: The term du jour for such an author would have been “man of science,” and that just didn’t fit Somerville.

In a pinch, the well-known wordsmith coined the term “scientist” for Somerville. Whewell did not intend for this to be a gender-neutral term for “man of science;” rather, he made it in order to reflect the interdisciplinary nature of Somerville’s expertise. She was not just a mathematician, astronomer, or physicist; she possessed the intellectual acumen to weave these concepts together seamlessly.

Somerville was an intellectual giant of her age. In her mathematical and scientific pursuits, she was able to converse confidently with some of the foremost minds in the natural philosophic community (natural philosophy previously having been the name of scientific endeavour). More so, she was able to do this without attending university, instead acquiring knowledge through her own self-teaching abilities.

Growing up in a lower middle-class household in Scotland, she received a basic education — though this was not any more than was expected of a girl at the time. It was only due to her boundless curiosity in the world around her which she cultivated through various countryside excursions, and through reading the books in her father’s private library, that she was given the spark that became a lifelong love of knowledge and explanation.

As her early academic interests, perceived as boyish, were shunned in the household, she was sent to learn needlework and domestic duties (both of which she met with annoyance). She still attempted to keep up with the more extensive education that boys in her town were provided with (and indeed often surpassed them).

As a maturing young woman of 18, she was introduced into society: attending balls and spectacles in Edinburgh and dancing with nobility. She was outwardly renown as a beauty and was married in 1804 to a wealthy physician.

With her free time as a provincial housewife, she now began to study seriously and continued this after she became a widow three years later. She read the works of Newton, Laplace, Lagrange, and others scientific notables.

By her early thirties, she was solving complex problems and publishing her results in philosophical journals of the time. For this she received awards and public notoriety.

An incredible polymath, she was adept in almost all areas of scientific pursuit. Her interests were so multi-varied and her abilities so keen that she was able to become knowledgeable in mathematics, physics, chemistry, geology, geography, and astronomy, as shown in the vast scope of her publications.

Her works On the connexion of the physical sciences’ and ‘Physical Geography remained staples years after her death. She was also able to speak Latin and Ancient Greek fluently. Biographer Renee Bergland claimed that ‘she was no mere astronomer, physicist, or chemist, but a visionary thinker’, and one who surmounted daunting mental obstacles

Beyond purely academic interests, she somehow also found time to push her political beliefs and aided in the fight to improve the rights of women. John Stuart Mill presented Somerville with his 1868 parliamentary petition for women’s suffrage — of which she provided the first signature.

She eventually became an image in her own right, espousing the ability of women to improve their situation through intellectual pursuit — to gain an equal footing with men in that regard would later be intrinsic to suffragist efforts. Even more so in her long list of achievements, she was tutor to another giant of mathematical science: Ada Lovelace, a pioneering force in computer mechanics.

As shown, Somerville’s life encapsulated so diverse a litany of achievement and she should act as testament to the power of knowledge to break down barriers. Her legacy was so great that her name was given to an Oxford College, one that was among the first to allow women to attend the ancient university. Among the names of those who helped push women’s liberation, she must be ranked as one of the foremost, though this is not understate her incredible scientific achievement. Certainly, the true testament to her legacy came in her obituary which read: ‘whatever difficulty we might experience in the middle of the nineteenth century in choosing a king of science, there could be no question whatever as to The Queen of Science.

467 notes

·

View notes

Text

Months after the publication of Somerville’s Connexion, the English polymath William Whewell — then master of Trinity College, where Newton had once been a fellow, and previously pivotal in making Somerville’s Laplace book a requirement of the university’s higher mathematics curriculum — wrote a laudatory review of her work, in which he coined the word “scientist” to refer to her. The commonly used term up to that point — “man of science” — clearly couldn’t apply to a woman, nor to what Whewell considered “the peculiar illumination” of the female mind: the ability to synthesise ideas and connect seemingly disparate disciplines into a clear lens on reality. Because he couldn’t call her a physicist, a geologist, or a chemist — she had written with deep knowledge of all these disciplines and more — Whewell unified them all into “scientist.” Some scholars have suggested that he coined the term a year earlier in his correspondence with Coleridge, but no clear evidence survives. What does survive is his incontrovertible regard for Somerville, which remains printed in plain sight—in his review, he praises her as a “person of true science.”

Maria Popova, Figuring

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I posted 312 times in 2022

145 posts created (46%)

167 posts reblogged (54%)

Blogs I reblogged the most:

@heaveninawildflower

@detroitlib

@uwmspeccoll

@riesenfeldcenter

@alachualibrary

I tagged 307 of my posts in 2022

Only 2% of my posts had no tags

#reblog - 162 posts

#othmeralia - 125 posts

#rare books - 43 posts

#old books - 33 posts

#othmer library - 29 posts

#chemistry - 23 posts

#digital collections - 23 posts

#science history - 20 posts

#special collections - 18 posts

#history of science - 18 posts

Longest Tag: 75 characters

#reminds me of the jello episode of the rugrats when the carmichaels move in

My Top Posts in 2022:

#5

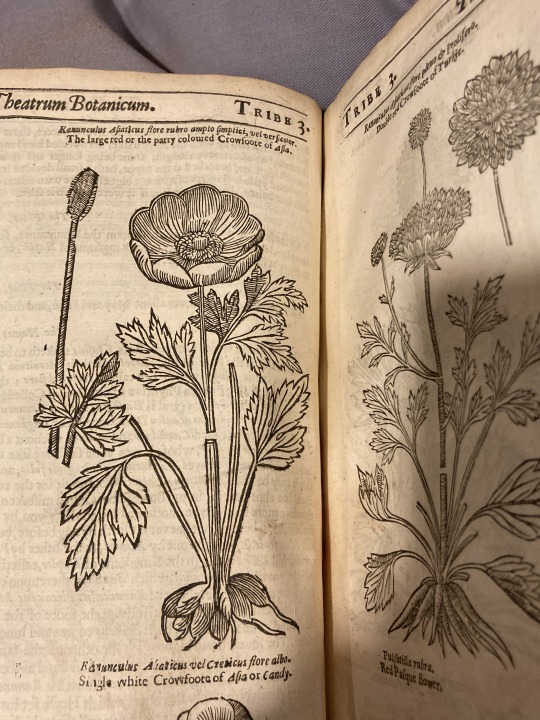

The large red or the party coloured Crowfoote of Asia would be make for such a nice tattoo! This woodcut comes from Theatrum botanicum (1640).

281 notes - Posted April 26, 2022

#4

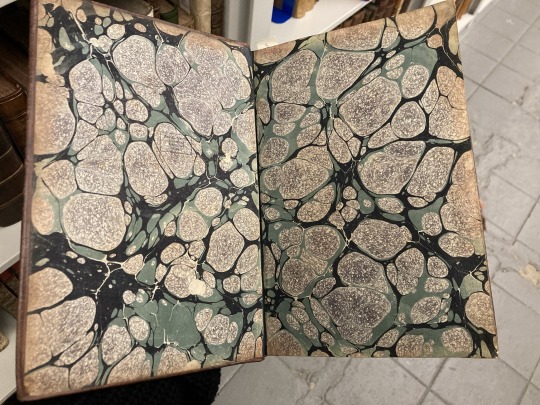

Marbled Monday!

This marbling is found in the English translation of Thaumatographia naturalis. The English title, get ready for this, is An history of the wonderful things of nature : set forth in ten severall classes : wherein are contained : I. the wonders of the heavens, II. of the elements, III. of meteors, IV. of minerals, V. of plants, VI. of birds, VII. of four-footed beasts, VIII. of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. of fishes, X. of man / written by Johannes Jonstonus ; and now rendred into English by a person of quality.

314 notes - Posted January 24, 2022

#3

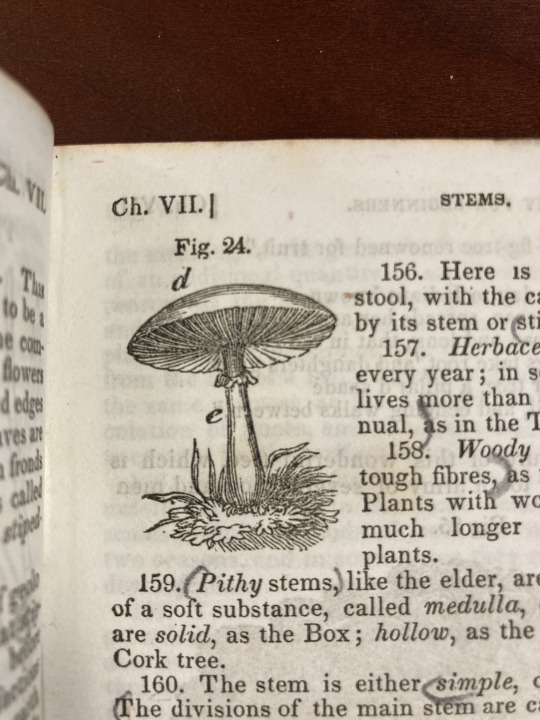

Searching for a little tattoo inspiration? Well we got you covered! This mushroom comes from Botany for beginners (1851). This would be really cute on the side of the ankle!

388 notes - Posted March 8, 2022

#2

The marbled fore-edges on this book are out of this world!

The book is The philosophy of the inductive sciences : founded upon their history by William Whewell (1840).

528 notes - Posted February 7, 2022

My #1 post of 2022

This bookplate never gets old. It's probably our favorite in the collection.

Found in: Traité des embaumemens selon les anciens et les modernes. Avec une description de quelques compositions balsamiques & odorantes ...

596 notes - Posted October 21, 2022

Get your Tumblr 2022 Year in Review →

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday 6 March 1836

7 ¾

11 ½

no kiss fine morning but dull - F34 ½° at 8 at which hour breakfast - A- off to the school at 8 55 I sat reading downstairs till 10 10 the latter ½ (had the former part on Friday) of ‘Six months in a convent: the narrative of Rebecca Theresa Reed, late inmate of the Ursuline convent mount Benedict, Charlestown, Massachusetts 2nd London edition, Reprinted from the American edition, with an Introduction London: Thomas Ward and co. 27 Paternoster Row 1836. William Tyler, printer, Bolt-cont, Fleet street’ 18mo. (or very small 12mo.) pp. 100 + viii pp. of Introduction 25,000 copies sold in Boston in a very few weeks - ‘which sale tended to increase rather than to lessen the demand for’ this little book - a lawless mob ‘has since demolished the building in which Miss Reed was confined’ no wonder! this little book, which bears the stamp of truth, as surely [?] to hold up the convent of Mount Benedict to the hatred of all honest men - ¼ hour looking into travelling books - out at 10 ½ to meet A- met Greenwood - he says something must be done about the Northgate hotel - some beer or something must be sold there, or the licence may be taken away - told G- to make inquiries and see after this - he wants me to let Carr have the hotel - I said C- had neither character nor money and the yellows were all against him saying he was such a party-man - gave Greenwood the key of my walk to look about him and asked him to come up some evening and talk matters over - we met A- at Mytholm and I turned back with her and left G- to look about having told him I hoped to have 18 horse-power to spare after pumping up the coal-water - came in at 11 20 - A- and I a minute or 2 with my father - at accounts till 12 ¼ -then A- and I read prayers to my aunt (in bed) and Oddy and Mary and John in 25 minutes - then sat with A- a little read the 1st 18 pp. of Whewell’s notes on German churches - at the school at 2 ¼ - waited 12 minutes in church till 2 ½ - Mr. Wilkinson did all the duty - preached 14 minutes from Ephesians v.14. called and sat an hour at Cliff hill - Mrs. AW- in good humour and spirits - home at 5 ¾ - dinner at 6 - coffee - read the first 20 pp. of a tour in Germany published in London in 1826 till 9 50 then 10 minutes with my aunt - dull but fair and finish day till 12 at noon - then rain and rainy afternoon - fair now at 10 20 pm and F38°

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since conversations between scientists and historians of science would benefit both, why are they so rare? History provides some insights. For almost two centuries, the increasing specialisation of the sciences has militated against the flow of information between the sciences and the academic humanities (and, indeed, among the sciences themselves). As early as 1834, the polymath scientist-historian William Whewell bemoaned the ‘division of the soil of science into infinitely small allotments’.

The missing conversation

To the detriment of the public, scientists and historians don’t engage with one another. They must begin a new dialogue

0 notes

Text

Alguém ainda se importa com bíblias?

Ciência, cientista. Apenas depois da 2ª G Mundial que a designação foi aceita para se referir ao profissional que se dedica à pesquisa científica, remetendo à famosa imagem do estudioso que fornece explicações com base em experimentos. Quem cunhou o termo foi o britânico William Whewell, em 1833. A partir disso, ele também se tornou um candidato a ser lembrado como um cientista. Mas, definitivamente, ele não é o primeiro da história, por mais que eventualmente atenda aos critérios da denominação. Tales de Mileto, o primeiro cientista Se considerarmos um nome da Grécia Antiga, Tales de Mileto é o que possui maior destaque nesse sentido. Grego, ele viveu entre 624 e 546 a.C. Mais do que famoso por ser o primeiro matemático, Tales também era filósofo, sendo fundador da Escola Jônica, e também se dedicava ao estudo de ciências. Graças a Heródoto, ele ganhou fama por prever a ocorrência de um eclipse solar no ano de 585 a.C. (mas há quem acredite se tratar de uma lenda). Naturalmente, apesar dele reunir tanto conhecimento, não se pode dizer que Tales dominava todos os assuntos. Como exemplo disso, temos o fato dele ter apontado que toda matéria se originava da água. Além disso, Tales, assim como seus conterrâneos, acreditava que a Terra era plana — e isso não é algo que pode diminuí-lo de alguma forma, considerando as informações disponíveis no período. Mas, esse antigo estudioso, ao se debruçar na resolução de problemas práticos e aliar conhecimentos de diferentes campos do saber, acabou sendo associado como o primeiro cientista da história. Contribuições científicas que dialogam Vale dizer ainda que Aristóteles (384 - 322 a.C.), por ter avançado no estudo dos fenômenos naturais, também é considerado por muitos como o primeiro cientista. Roger Bacon (1220 - 1292), mais adiante, ao valorizar o empirismo, também é lembrado da mesma forma. Galileu Galilei (1564 - 1642) ainda é tido como o primeiro desde da era moderna. E em meio a essa busca, há outro nome do mundo árabe que eventualmente é citado. Trata-se de Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazém, na forma latinizada), que viveu entre 965 e 1040. Nascido no Iraque, ao se aprofundar no estudo da luz, ele buscou entender como se dá a refração, e qual trajetória que a luz percorre ao atravessar o olho humano. E ainda que não tenha fornecido todas as respostas, ofereceu um caminho até elas. O trabalho de Ibn al-Haytham influenciou outros grandes nomes, como Johannes Kepler (1571 - 1630). Inclusive, o método adotado pelo árabe remete àquilo que conhecemos hoje como o método científico moderno. No final das contas, ainda que Tales de Mileto seja reconhecido como o primeiro cientista, todos esses nomes abriram portas, permitindo que aqueles que exploravam assuntos relacionados do seu campo de estudo pudessem avançar rumo às próprias descobertas. Dessa forma, com contribuições que dialogam entre si e estão presentes em muitas invenções do mundo contemporâneo, esses cientistas permanecem lembrados por seus esforços.

0 notes

Text

SciZone

Science is a system of knowledge that is concerned with the physical world and its phenomena and that entails unbiased observations and systematic experimentation. Science can be divided into different branches based on the subject of study, such as physical sciences, biological sciences, and social sciences. Science also involves a pursuit of knowledge covering general truths or the operations of fundamental laws.

Some facts about science are:

The word science comes from the Latin word scientia, which means knowledge.

The scientific method is a process of making observations, asking questions, forming hypotheses, testing them, and drawing conclusions.

The first person to use the term scientist was William Whewell in 1833.

The most cited scientific paper of all time is Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent by Oliver H. Lowry and colleagues, published in 1951.

The largest science experiment in the world is the Large Hadron Collider, a particle accelerator that spans the border between Switzerland and France.

SciFunZone

Why did the chicken go to the séance? To get to the other side.

How do you tell the difference between a chemist and a plumber? Ask them to pronounce unionized.

What do you call a fish made of two sodium atoms? 2 Na.

What do you get when you cross a mosquito with a mountain climber? Nothing. You can’t cross a vector and a scalar.

How many physicists does it take to change a light bulb? Two. One to hold the bulb and one to rotate the universe.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Istilah 'ilmuwan' (scientist) dimunculkan pada tahun 1830-an oleh William Whewell (1794-1866), seorang fisikawan dan sejarawan ilmu; sebelumnya ilmuwan dipandang sebagai 'filsuf alam'. Whewell memandang ilmuwan sebagai seseorang yang terlibat dalam peranan sosial yang unik, yang memerlukan proteksi dan memiliki eksistensi otonom dibandingkan anggota masyarakat lainnya.

Referensi: Ziauddin Sardar, “Thomas Kuhn dan Perang Ilmu”, hlm. 7; diterjemahkan dari “Thomas Kuhn and the Science Wars” oleh Sigit Djatmiko, diterbitkan oleh Jendela pada Oktober 2002.

0 notes

Text

Every failure is a step to success.

— William Whewell

0 notes

Quote

"Every failure is a step to success."

https://www.brainyquote.com/authors/william-whewell-quotes

0 notes