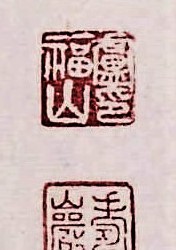

#Zhou Cezong Collection

Text

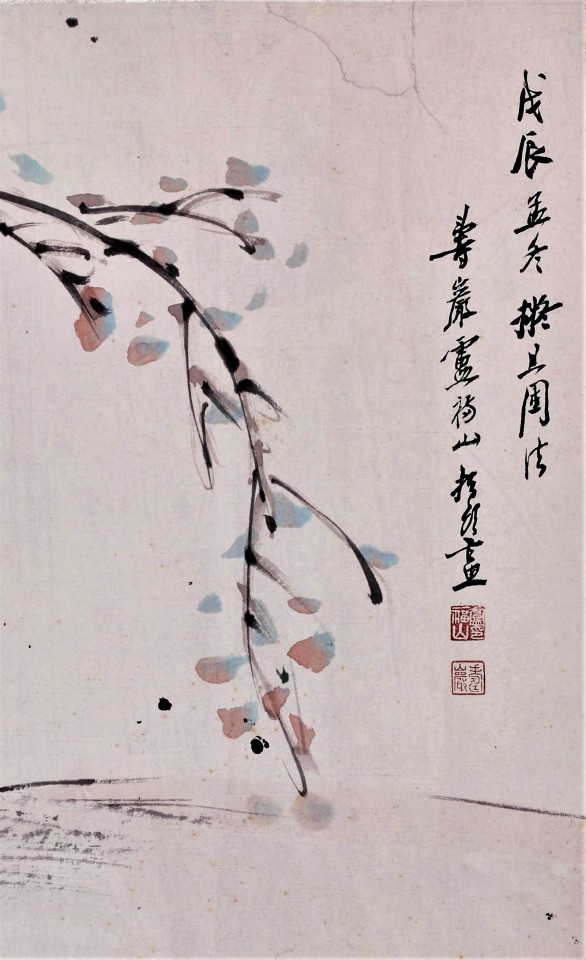

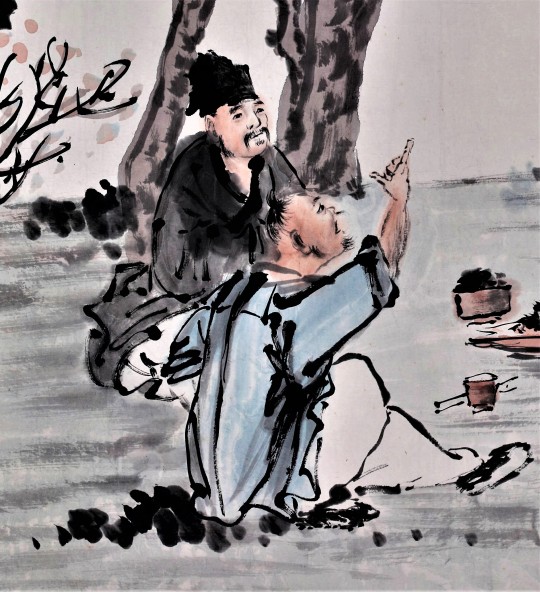

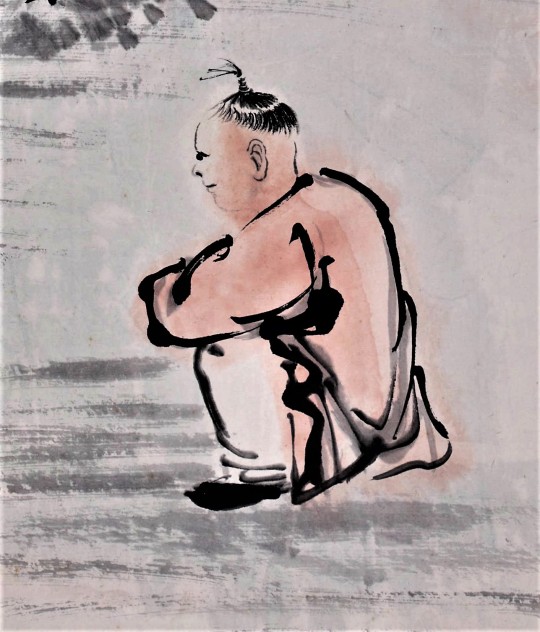

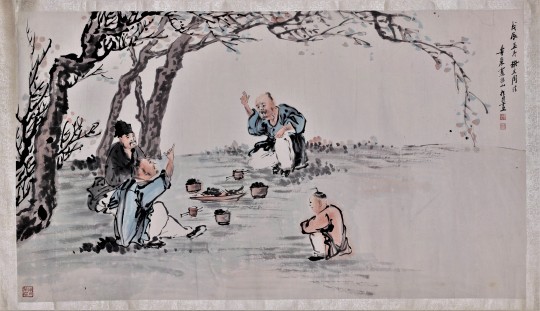

Chinese Finger Painting

Traditional Chinese finger painting uses the tips of the fingers and the nail instead of a brush to paint on surfaces. This style of painting offers a spontaneous and somewhat impressionistic presentation. The painting shown from the early 20th century is drawn from our Tse-Tsung Chow Collection of Chinese Scrolls and Fan Paintings. It appears to depict a rather animated discussion over a picnic meal. The title doesn't help much, it simply notes that this is Fushan Lu's figure finger painting executed in winter.

We know quite a bit about many of the artists in our Chinese calligraphy and painting collection, but we know nothing about Fushan Lu, whose art name is Shouyan. Still, he seems to be a very accomplished finger painter. There are three Chinese seals or chops, one for Fushan Lu, another for Shouyan, and the third for the collector, Zhou Cezong (i.e., Tse Tsung Chow).

View more posts from our Tse-Tsung Chow Collection.

#Chinese finger painting#Chinese paintings#finger painting#Chinese scroll paintings#Chinese art#Fushan Lu#Shouyan#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection#picnic

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Snow Day Thursday

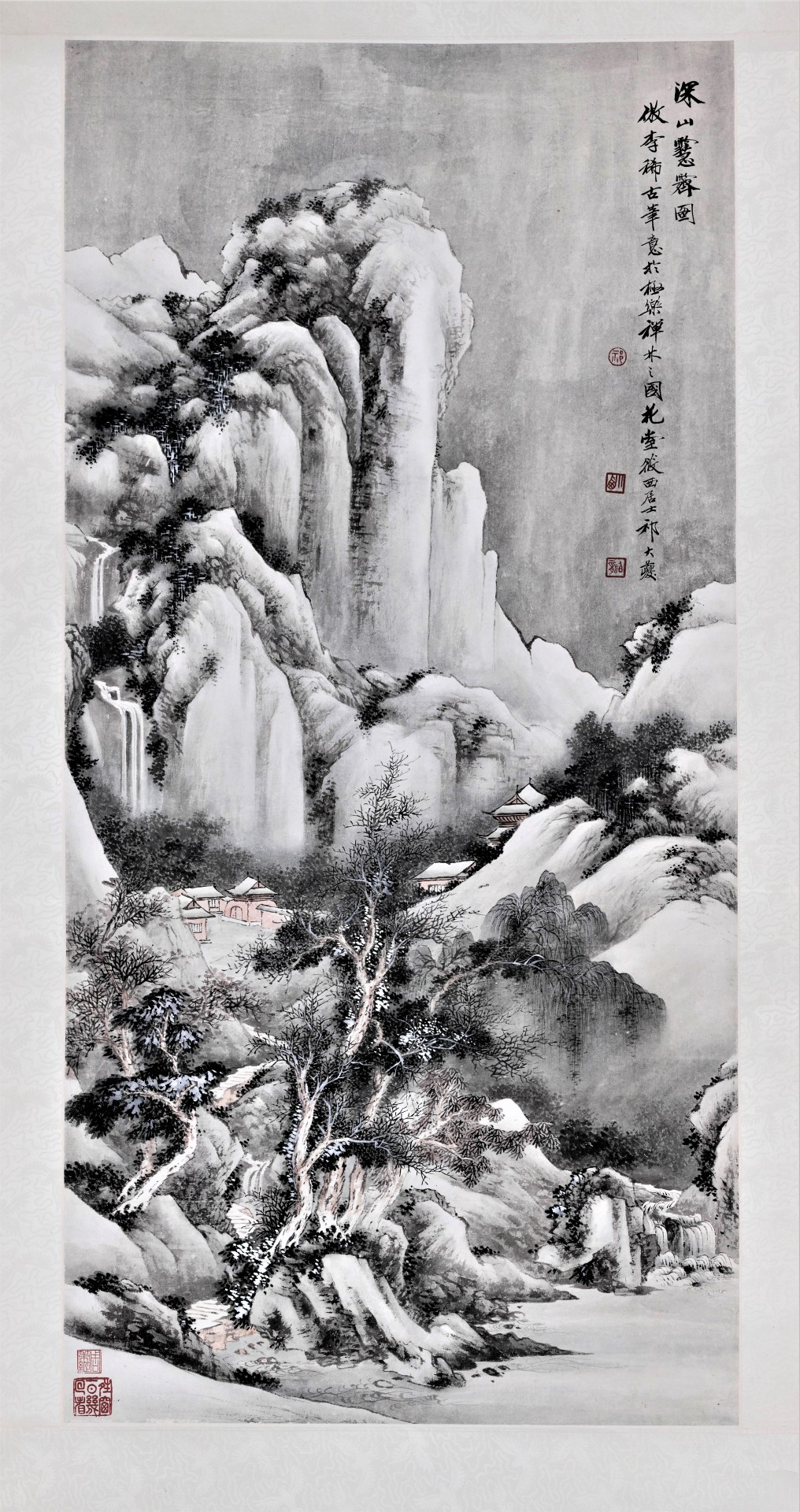

We are being hit by Winter Storm Elliott, so we will be closed for the day and very probably tomorrow as well. To reflect the snowy clime, we present a Chinese scroll painting entitled Qi Dakui's picture of snow in the deep mountains (imitating the brushwork of Li Tang [Xi Gu]) - 祁大夔深山雪霽圖(仿李唐(晞古)筆意, from our Tse-Tsung Chow Collection of Chinese Scrolls and Fan Paintings.

Qi Dakui (1921-1982), known by the pseudonym Xiao Xi Ju Shi, was born in Beijing and specialized in landscape painting. His father, Qi Kun, was also a renowned landscape painter during the beginning of Republic of China. This ink-wash style of painting is known as Shuimo. Here, Qi is emulating the style of the noted 11th-century Chinese painter Li Tang (c. 1050 – 1130).

There are five Chinese seals or chops. They read: 1) 祁 - Qi; 2) 小西 - Xiaoxi; 3) 伯龍 - Bolong; 4) 周策縱 - Zhou Cezong (i.e., Tse Tsung Chow); 5) 晴窗一日幾回春 - Seeing spring scences several times a day from sunny windows.

View more posts from our Tse-Tsung Chow Collection.

#Snow day#Chinese scroll paintings#Chinese art#Qi Dakui#snow in the deep mountains#snow#Li Tang#Shuimo#ink wash painting#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Chinese seals#Winter Storm Elliott

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Figure 1. Jiang Biao’s fan calligraphy, UWM Special Collections (cs 000089).

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work,

Part 10

For the next two weeks, we will focus on the artistic dichotomy of Zheng (正, normative or orthodox) and Qi (奇, unusual or strange ) between five fin de siècle calligraphic fans in our Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work. and the work of calligrapher Fu Shan (1607-1684). Zheng is a conservative style, relying on established styles and techniques. Qi is an idea of originality, requiring artists to break from social and political conventions, and challenging recognized norms. According to art historians Dora Ching and Katharine Burnett, the first half of the seventeenth century witnessed Qi as one the primary markers of Chinese art history, which was represented by Fu Shan and a few others. Fu claimed that he would rather have his calligraphy be awkward, not skillful; ugly, not pleasing; deformed, not slick; spontaneous, not premeditated. However, after 1670, this revolutionary pursuit was held in thrall to the prescribed reiteration of Zheng until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Kang Youwei (1858-1927) made an emotional harangue against the latter’s stultifying nature.

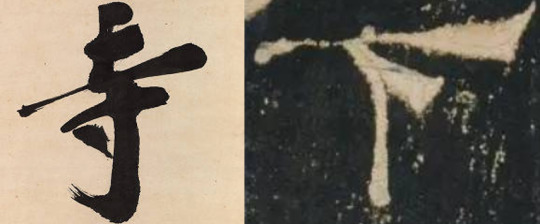

(From left to right): Figure 2 (a): Detail from rom Figure 1; Figure 2 (b): Detail from the Stele of Mount Yi; Figure 2 (c): Detail from Fu Shan’s work.

The fan in Figure 1 is a small seal script (first appeared in Qin Dynasty: 221-207 BCE) written by Jiang Biao (1860-1899), the educational commissioner who worked with Chen Sanli (see my previous blog) during Hunan Reform from 1897 to 1898. The format of his characters (Figure 2a) drew inspiration from the Stele of Mount Yi (Figure 2b), which contains a quintessential small seal script created around 219 BCE. Both of them emphasize a balanced, neat, and standardized form, symbolizing the main features of Zheng.

However, in Fu’s view, Zheng style was the degeneration of Chinese calligraphy, and only by deviating from this orthodoxy can one’s works attain vitality and the spirit of nature. One of his ways to achieve this vitality is to exaggerate parts of his composition. In Figure 2c, he first stylized the top half of the character to a wiry linearity; then he exaggerated the bottom half with a fluffy and ostentatious curvature. By these exaggerations, the character produces a strong visual contrast and awkward rawness, exhibiting a feeling of novelty and surprise.

Figure 3. Jin Nong’s Guanyin (Bodhisattva).

From Zhongguo meishu quanji, Huihua bian 11 中国美术全集, 绘画编, 第11卷 [The Collections of Chinese art: Painting Section, volume 11](Shanghai: Shanghai renmin meishu chubanshe, 1988), 29.

Fu’s exaggerated presentation of Qi is also manifested by another iconoclastic artist Jin Nong (1687-1763) in the middle of Qing Dynasty. As a great literati-artist, Jin’s paintings retained a charismatic, somewhat whimsical flavor which derived in part from his amateurish exaggeration. In Figure 3, the head of Guanyin (Bodhisattva) is foreshortened to a restricted rectangular space, while his swirling and gargantuan drapery is expanded and elongated to a scope that strains credulity. The stark contrast of the proportion between his head and body is reminiscent of Fu’s audacious approach in Figure 2c.

Figure 4. Peng Yunzhang's fan calligraphy, UWM Special Collections (cs 000094).

The second fan (Figure 4) is a clerical script by Peng Yunzhang (1792-1862), a high official in late Qing Dynasty. Derived from small seal writing, the structure of clerical style is undulating and flaring. For instance, the horizontal stroke will begin with a rounded head similar to a silkworm cocoon and end with a wavelike flourish resembling the tail of wild goose (see the last horizontal stroke in Figure 5). This style reached its zenith during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 CE); and it marks the conclusion of ancient pictographic script and heralds the beginning of the current system of writing.

Figure 5. Detail from Figure 4.

Figure 4 is a faithful imitation of the Ode of XiXia Pathway, which is a cliff stele designed to commemorate governor Li Xi’s achievement to construct a pathway along the face of a precipitous cliff around 171 CE. Peng’s fan possesses the easygoing poise and smoothness of the original stele. However, the character in Peng’s writing is too elegant and orthodox (Zheng), bordering on banality and rigidity. On the contrary, Xixia’s character is imbued with improvised kinetic variations.

Specifically, in terms of structure, Peng’s layout is properly arranged and equally spaced (Figure 6a), whereas in Xixia (Figure 6b), imbalance is the leitmotif---at first glance, the three parallel strokes on the top right give a vertiginous illusion and structural disharmony; nonetheless, they echo the three tilting horizontal strokes on the left. By following an invisible diagonal line, Xixia pushes a directional force that invites audiences to view the images from an oblique angle. This diagonal perspective does not run out of control; instead, it is perfectly buttressed by two prominent perpendicular strokes and two arch-like components in the character, thereby bringing a kinetic balance to the overall structure.

(From left to right) Figure 6 (a): Detail from Figure 4; Figure 6 (b): Detail from Ode of XiXia Pathway; Figure 6 (c): Detail from Fu Shan’s work.

As an advocate of Qi, Fu viewed imbalance as a barometer of his pursuit of Qi. Xixia’s masterful control between imbalance (diagonal kinesthetics) and balance (perpendicular buttress) might serve as the epiphany for his experimentation. In Figure 6c, the three skewed strokes on the top and the two leftward cocoon-shaped dots on the left are joined to create an imbalanced diagonal. However, the central 口and its two supporting vertical lines act as a counterweight to stabilize that imbalanced balance. In this case, the unusualness of Qi does not transgress the boundaries of accepted conventions; rather, it just brings a precipitous visual contrast to animate the stereotypical practices.

Figure 7. Eugen Kirchner’s November (from the MOMA collection).

The use of imbalanced balance in a diagonal composition can also be seen in Western paintings. In the aquatint November (Figure 7), Eugen Kirchner (1865-1938) adopts a similar arrow-like diagonal to push the silhouettes of people to their furthest depth (a compositional imbalance). The pronounced diagonal perspective amplifies the blusteriness of the weather (an environmental imbalance), and indicates a sense of dreariness and angst (a phycological imbalance) within the throng. However, the erection of the road sign in the middle right not only works as a supporting counterweight to the composition, but also attenuates the stress from the environmental and phycological imbalance. The road sign is unaffected by the wind and the people move freely to almost a same direction. Here, the imbalanced diagonal is balanced by a vertical sign in regards to the compositional, environmental, and phycological perspective.

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Jingwei#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese fans#Chinese history#art history#Fu Shan#Jiang Biao#Jin Nong#Peng Yunzhang#Eugen Kirchner#Zheng style#Qi style#small seal script#clerical script#Ode of XiXia Pathway#Stele of Mount Yi#Zhou Cezong Collection#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Figure 1. Liu Kunyi’s Portrait

Figure 2. Liu Kunyi’s scroll (UWM Special Collections, cs000103)

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 7

This week we concentrate on a calligraphic hanging scroll (Figure 2) by the late 19th-century Chinese government official Liu Kunyi (1830-1902, Figure 1) from Special Collections’ Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

In previous blogs, I mentioned the interchangeability between artistic style and the artist’s temperament. However, for Chinese masters, the content of the artwork should also be considered. In this scroll, the content reads:

Prune flower will invite butterfly; pile rockery will invite cloud; plant pine will invite zephyr; sow willow will invite cicada; reserve water will invite duckweed; build terrace will invite moon; grow plantain will invite rain; collect book will invite friend; and accumulate morality will invite heaven.

This scroll is executed with the gentle rhythm and measured control---the plumpness of the brush style is partly derived from the semi-cursive writing (Figure 3) of Zhao Lingzhi (1051-1134), with the artistic idiom of Su Dongpo (1037-1101) as the common progenitor. The brushstroke not only reflects the author’s leisure, buoyancy, and composure, but also matches the idyllic scenery and natural vibrancy from the text. According to Qi Gong, the great connoisseur of Chinese painting and calligraphy, it would be improper for calligraphers to use the round and majestic strokes of Yan Zhenqing (709-785) to transcribe a subtle and romantic lyric; likewise, it is objectionable to apply the graceful lines Chu Suiliang (596-658) to depict the coarse utterance of a scoundrel in a drama. Hence, the tripartite fusion within art, temperament, and content is regarded as one of the most complicated topics in Chinese art history.

Figure 3. Zhao Lingzhi ‘s calligraphy (from the Digital Archive of the National Palace Museum)

Figure 4. Detail from Figure 2

Figure 5. Mi Fu’s calligraphy (from ColBase: Integrated Collections Database of the National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan)

It is important to note that apart from this leisurely gentleness, the artwork pulsates with confidence. The Flying White in Figure 4, a white discontinuous streak in the stroke created by the swift movement of the brush, indicates the author’s following of Mi Fu (1051-1107)’s style, which resembles “a swift horse cutting through an encampment (Figure 5).” This confidence is also indicative of Liu’s great success in the late Qing politics.

As the governor-general of Liang Jiang (Jiangshu, Jiangxi, and Anhui Province) and the superintendent of trade for southern ports (Duan Fang, who I mentioned in my last post, was his later successor), Liu was an most important forerunner in initiating the government-lead modernization movement at the beginning of 20th century. On July 1902, Liu and Zhang Zhidong (1837-1909), another powerful viceroy of the country, submitted three joint memorials to the throne advocating new policies in order to achieve political modernization. Though he did not problematize the issue by stipulating specific regulations to practice constitutionalism and promote human rights, his farsightedness compelled the court to make a dramatic reversal in a centuries-long system, and move toward the steady construction of a more powerful modern state.

His confidence might also be connected with his two incredible disobediences to the court: first, in the early spring 1900, he was instrumental in blocking the Empress Dowager’s scheme to depose the Guanxu Emperor---the involvement of governors in the alternations of the throne was unprecedented in Chinese modern history; secondly, on June of the same year, he openly disobeyed the Empress Dowager’s edit to exterminate all foreigners in China. Negotiating with the foreign consulates without the imprimatur from the government, he had the audacity to sabotage the court’s order and assumed responsibility to protect foreign lives and properties within his jurisprudence (Duan Fang did the same thing). His extraordinary courage protected southern China and left it unscathed from the political melee, paving the way for the later reform initiative.

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Jingwei#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese scrolls#Liu Kunyi#Chinese politics#Chinese political reforms#Chinese history#art history#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Figure 1: Kang Youwei’s Portrait

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work

Hi everyone! Recently, I began working in UWM Special Collection as a graduate Art History researcher to investigate some the Chinese art scrolls and fans from the collection. Most of these works came from a donation by Professor Zhou Cezong (1916-2007) and his wife Nancy Wu.

Today I want to introduce you to one important artwork in the collection, a couplet on two scrolls (Figures 2 and 3) that was created by Kang Youwei (1858-1927, see Figure 1) during 1920s. The couplet suggests Kang’s ideology of being a scholar. Flowers and bamboo are used as metaphors for the ideal of the scholar: “Flowers and bamboos symbolize the spirit of elegance and being aloof from worldly pursuits. A status with virtue of grace and being indifferent to fame is where my heart goes to.”

As the leader of the Hundred Days’ Reform (June 11 to September 22, 1898), Kang was one of the most audacious and provocative political figures in Chinese modern history. Before the reform, Guang Xu Emperor asked several high officials negotiating with him. One of them questioned Kang’s plans by saying “how can we change everything overnight?” He replied, with great resolution and courage, “by killing several high officials, then the reforms will run out smoothly!”

Kang was a fervent patriot and constitutionalist. For the reform, he designed a very systematic plan to abolish the old systems and construct a system of modern governance. However, his radicalization ultimately led the reform to failure---the emperor was imprisoned, the leading figures were executed, and Kang was sent into long exile abroad.

In Kang’s later life, he did not continue the momentum of his reforming ambition; instead, he became a reactionary of resistance to forthcoming revolutions. When he heard about the outbreak of the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, he was “distraught,” and cursed it to be abortive. In 1917, he even joined with Zhang Xun (1854-1923) to restore the abdicated emperor. In his opinion, “the rise of the democracy would only increase the violence from the mob;” and only by “returning to the Confucian doctrines (i.e., the symbol of feudal governance)” could the country be saved from damnation.

Our UWM couplet (see Figure 2 and 3) was mounted around 80 years ago and is still in perfect condition. The brush strokes are cursive and succinct, expressing great determination and spontaneity, as if indicating Kang’s ambition to wipe out the old stereotypical practice. The second stamp in second couplet (Figure 4), which is printed upside down and reads “Spending 16 years in exile, travelling all over the world 3 times, visiting 4 continents, passing through 31 countries and walking 600 thousand miles,” is one of the most interesting stamps in the modern Chinese art history, which can also be seen as the summation of author’s controversial and legendary life.

Figure 2: UWM Special Collection (cs ooo114a), the first couplet

Figure 3: UWM Special Collection (cs ooo114b), the second couplet

Figure 4: second seal in the second couplet (cs ooo114b)

-- Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher

#graduate research#Chinese scrolls#Chinese calligraphy#calligraphy#art history#Kang Youwei#couplet#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection#Jingwei

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

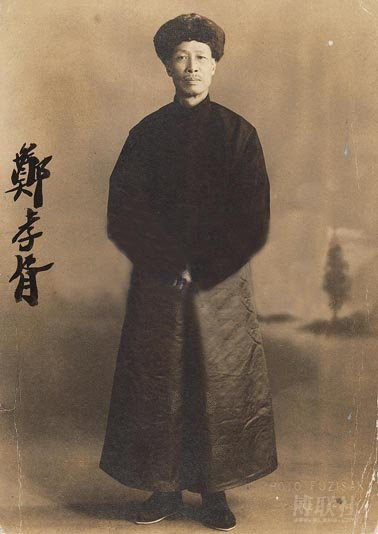

Figure 1. Zheng Xiaoxu’s Portrait (from The Mad Monarchist)

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 9

This week we turn our eye to two undated couplets (Figures 2 and 3) by Chinese statesman, diplomat, and calligrapher Zheng Xiaoxu (1860-1938, Figure 1) from our Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

According to celebrated Chinese writer Lin Yutang (1895-1976, twice nominated for Nobel Prize in Literature), in appreciating Chinese calligraphy, “the meaning is entirely forgotten, and the lines and forms are appreciated in and for themselves.” Thus, let’s skip the literal meaning of these two couplets and just focus on their lines and structures. And hopefully, this focus will help us to date them.

Figure 2. UWM Special Collections (cs 000004)

Figure 3. UWM Special Collections (cs 000054)

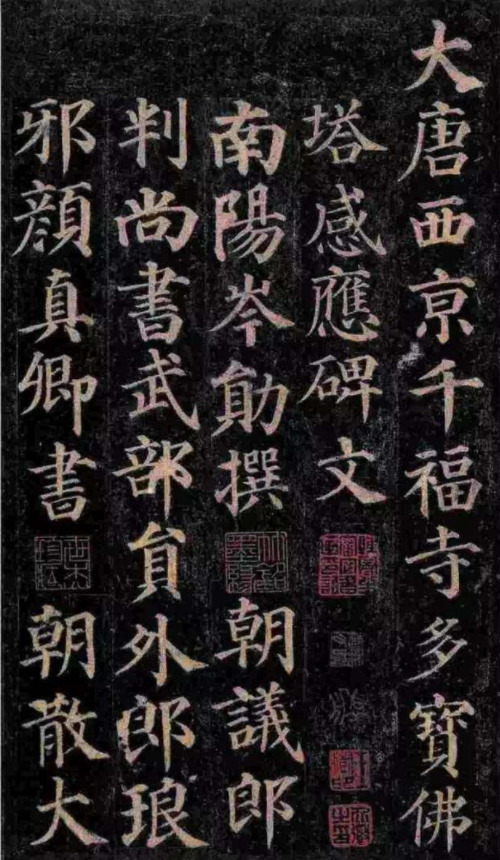

In 1889, Zheng became the protégé of Weng Tonghe (1830-1904), who was Guanxu Emperor’s teacher and one of the most supportive figures of the Hundred Days’ Reform. Influenced by Weng’s artistic taste, Zheng regarded the calligraphy of Tang Dynasty calligrapher Yan Zhenqing (709-785) as a model. In one Zheng’s early calligraphic examples (Figure 4), he exhibited a distinctive, plump, and powerful stroke with a well-knit, balanced structure, which is similar to Yan’s Record of Duobao Pagoda (Figure 5, the forefather of brushwork in standard writing) written in 752. In addition, Zheng imitated Yan’s round brush by adopting “hiding” and “protecting” movement of the brush tip (according to ancient calligraphic theorist Cai Yong, calligraphers should “hide the head” and “protect the tail” of the brushstroke). However, because the turn and thrust is limited, the image is static and frontal, confined to a flat linear schema, and showing rigidity and lassitude.

Figure 4. Zheng’s Early Calligraphy (from this source)

Figure 5. Yan Zhenqing’s Record of Duobao Pagoda (from this source)

Immediately after Xinhai Revolution in 1911, Zheng spent some time in Shanghai with his boon companions such as Chen Sanli, whom I discussed in a previous post, and Shen Zengzhi, whose cursive hanging scroll is also preserved in our Zhou Cezong Collection. During this period, he maintained an eclectic interest in ancient calligraphic rubbings, such as those from stone inscriptions, epitaphs, Buddhist votive stelae, and cliff engravings created in the Han (202 BC-220 AD) and Northern Dynasties (386-581). Our first couplet in Figure 2 is the epitome of his inclusive studies of the stelae. For instance, the longest horizontal stroke of 寺 (Figure 6) presents a dramatic thinning-and-thickening brush movement, which is akin to brush style of the horizontal line in下(Figure 7) from the Stele on Ritual Implements in the Confucian Temple (Liqi Stele, dated 156 CE). According to Yang Shoujing (1839-1915), whose work is also preserved in our collection, this stele has an eccentric instability concealed in the level-headed stability; and a strict denseness hidden in the elegant sparseness. Zheng’s 寺 is the symbol of this contradictory yet complementary comment. Another example of Zheng’s cross-fertilization could be detected in the character “分” and “明” in Figure 8. The rigid 丿 in “分”, and the rugged 𠃌 in “明” can find similar genealogical traits from their counterparts in Figure 9, which is from Yang Dayan Zao Xiang Ji created around 506 AD. Here, Zheng’s previous flat schema has been transformed to some contrasting variations in a sense of two-dimensionality, bringing vitality to the works. Nevertheless, the rigidity still permeates; and ruggedness is also his Achilles’s heel, indicating a smidgen of strenuousness, which is at variance with Chinese artistic standard of naturalness.

Figure 6: Detail from Figure 2. Figure 7: From Liqi Stele (Palace Museum Collection)

Figure 8: Detail from Figure 2. Figure 9: From Yang Dayan (Harvard Collection).

From 1906 to 1907, during the excavation in the deserts of Northern China, Sir Marc Aurel Stein found a group of wooden slips with calligraphic inscriptions written around 98 BC. In 1912, his friend Édouard Émmannuel Chavannes sent the copy of these slips to Luo Zhenyu (1866-1940), whose couplet scroll in Oracle Bone script is also preserved in our Zhou Cezong Collection. Luo invited Wang Guowei (1877-1927, Liang Qichao’s friend), a great sinologist, to collate, edit, and interpret those slips, which became the famous monograph entitled Liu Sha Zhui Jian (The Lost Wooden Slips Excavated in the Flowing Sands) published in 1914.

When Zheng saw this publication, he was enchanted by the calligraphic values of these slips, as he contended that with the finding of these slips, the secrecy of calligraphy would be thoroughly revealed. Generally speaking, compared with the standardized clerical writing in Figure 7, the running or cursive characters on these slips were rendered with undulation and flexibility (see Figure 10 and 11), devoid of axial balance and austere sublimity. By turning and flicking the brush in a silent pirouette on the paper, the slip writer constantly changed in speed and direction, suggesting a strong foreshortening and movement in space. This untrammeled style significantly enlivens Zheng’s artistic idioms. In Figure 12, the slanting angle and the flaring, wavelike motion of the second horizontal stroke bears uncanny resemblance to those of the first horizontal stroke in Figure 10. The brush is fully articulated in a vivacious spontaneity, carrying a natural three-dimensionality.

(From left to right) Figure 10: From Luo Zhenyu, Liu Sha Zhui Jian, p. 65. Figure 11: From Liu Sha Zhui Jian, p. 64. Figure 12: Detail from Figure 3.

From these three works, Zheng shows his audience the evolution of his mimetic representation. For the first phrase (Figure 4), his imitation of Yan was restricted by insipid flatness and slight flexure. After 1911, his exploration to ancient stele rubbings (Figure 2) gave his works a contrasting vitality, though the rigidity still lingers. For the final phrase (Figure 3), the pristine style of the wooden slips provided him a fresh impetus to awaken his vivacity, creating organic relationship in the image.

Figure 13. Three Greek Statues (from ca. 560 BC to 480 BC)

From Wen C. Fong, Art as History: Calligraphy and Painting as One (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 113.

The art historian E. H. Gombrich once made a similar-style comparisons for a group of ancient Greek statues (Figure 13). Naming them as the representation of the “Greek miracle” which illustrated the advancement of Western European civilization, he indicated in pictorial representation, archaic art began from restricted frontal schema, and then moved to the gradual adjustment to the natural appearances. This phenomenon can be equally applied to analyze Zheng’s work, which could be seen as his gradual accumulation of corrections due to the observation of ancient artworks.

Chinese art historian Wen C. Fong proposed the possible reason for this phenomenon. He noted that the disillusionment of the ancient literati with Chinese politics made them “turn away from the world of human affairs” and sought spiritual solace in the pursuit of artistic and literary expression. The impulse to express themselves in art led to the enlivening of Chinese art and civilization. Zheng is the exemplar of this explanation. He was once a most celebrated constitutionalist in the late Qing. After 1911, he lived in Shanghai as a loyalist to the defunct Qing Dynasty until February 1924, when he went to the Forbidden City to serve as a trusted advisor to Puyi (the last Chinese emperor, 1906-1967). Within these thirteen years, he became disillusioned with politics, and began to regard art as his safety valve, thereby pushing the boundaries of his artistic practices.

From these analyses, we can hypothesize that these two couplets in Special Collections were created during the same period of time (1911-1924). Figure 2 was created first, foretelling the coming of the more mature style in Figure 3. Most importantly, these analyses give us a good example to see how the student and scholar of Chinese calligraphy may use brushstroke and structure as evidence to evaluate, authenticate, and date artworks.

After Puyi and Zheng were evicted from the palace in November 1924, they settled in the Japanese concession of Tianjin. In 1931, under Zheng’s arrangement, Puyi went to Manchuria and became the leader of the Manchurian state, Manchukuo. Zheng became the regime’s Prime Minister with Japanese support. This collaboration with the Japanese tarnished the reputation of Zheng’s previous political and artistic achievements.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Jingwei#Chinese scrolls#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese art#Zheng Xiaoxu#Yan Zhenqing#Chinese politics#calligraphy#art history#couplet#Zhou Cezong Collection#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Figure 1. Ruixi’s fan (UWM Special Collections, cs000088)

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 6

This week we focus on a fan painting by Rui Xi (Figure 1) from the Zhou Cezong Collection in order to explore Chinese literati art and and the achievements of Chinese political reformer Duan Fang (1861-1911) in the late Qing period.

Ruixi is not an artist well known to the public. However, his fan painting exhibits many symbolisms of literati art. According to Chen Shizeng (1876-1923, whose father Chen Sanli I discussed in an earlier post), the essence of literati art is to reveal the temperaments and mentalities of the scholar-artist, rather than simply mimicking artistic technique and natural likeness. In this work, the contour lines are rendered by blunt and wiry energy, showing a strong affinity with the archaic look of seal-script calligraphy. The cascading waterfall and the misty atmosphere are imbued with spirituality. The hanging branches on the background cliff are depicted without roots, indicating a brusque and expressive spontaneity. The elegant inscription at the top not only creates a balance for the composition, but also reflects Ruixi’s extraordinary scholastic esthetics. The inscription reads:

I had a sudden whim to write the following inscription. My elder consanguineous brother Duan Fang---what do you think of it? I want to build an elegant house to settle my wife and children. All my eye can see is the sceneries of the mountain; all my ear can hear is the sound of rivulets; all I indulge in are paintings and books; and all I care about are the flowers and grasses. When I am happy, I will stay in a boat; and I will just let the boat take me anywhere. I am excited to have friends around but I am also self-contented when nobody around. Little brother Ruixi.

In this inscription, Ruixi portrays Duan Fang as a relative with a common ancestor. Since Duan Fang was of the Manchus, Ruixi might also have Manchu lineage.

According to Liang Qichao (whom I also posted about earlier), Duan Fang was the strongest Manchu supporter of constitutional reforms. Unlike Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao who liked to harangue with their slogans, he was dedicated to the concrete action of the reform. Playing a decisive role to convince Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) to enact the political reform, he was sent with four other high-ranking officials to visit Japan, the United States, and the principal countries of Europe to study the various systems of parliamentary or constitutional government. The Empress expressed that she would depend on Duan’s suggestions on whether China should implement a parliament and constitution when he returned from this mission. During the trip, the Imperial Constitutional Commission met with President Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of State Elihu Root, and Duan sent items from his personal bronze collection as gifts to various leaders and agencies. In extensive American press coverage, Duan was extolled as “the most active and determined reform leader in the empire.” Moreover, his “bronze diplomacy” also catapulted him to international fame.

Upon his return to China, he clandestinely invited Liang Qichao to draft a two-million-word report on reform under his name. It stressed the necessity and exigency to establish a constitutional government in China, which not only propelled the court to reform, but also sheds light on democratic discourse in the early twentieth century.

In early 1911, the court’s decision to nationalize the railway incited furor and riot in Sichuan Province, which then escalated into the Xinhai Revolution. Duan was entrusted to suppress the opposition. On November 27, a mutiny among his troops revolted against him and he was assassinated. Three months later, the Qing Dynasty collapsed with the abdication of Puyi. According to Thomas Lawton, the noted historian on Chinese art, Duan’s death could be interpreted as a symbol of the fall of imperial China.

Aside from the Freer Gallery and the Nelson-Atkins Museum with their abundant holdings of objects from Duan’s collection, almost every museum in the world with a Chinese collection contains some artifacts that would have once passed through Duan’s hand. One of his most famous bronze collections is showed in Figure 2 and Figure 3, which is now housed in Metropolitan Museum.

Figure 2. Bronze Altar Set

Figure 3. Duan Fang (to our left of bronzes) and the Altar Set

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Chinese fan paintings#Duan Fang#Rui Xi#Chinese politics#Chinese literati art#Chinese bronzes#art history#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection#Jingwei

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

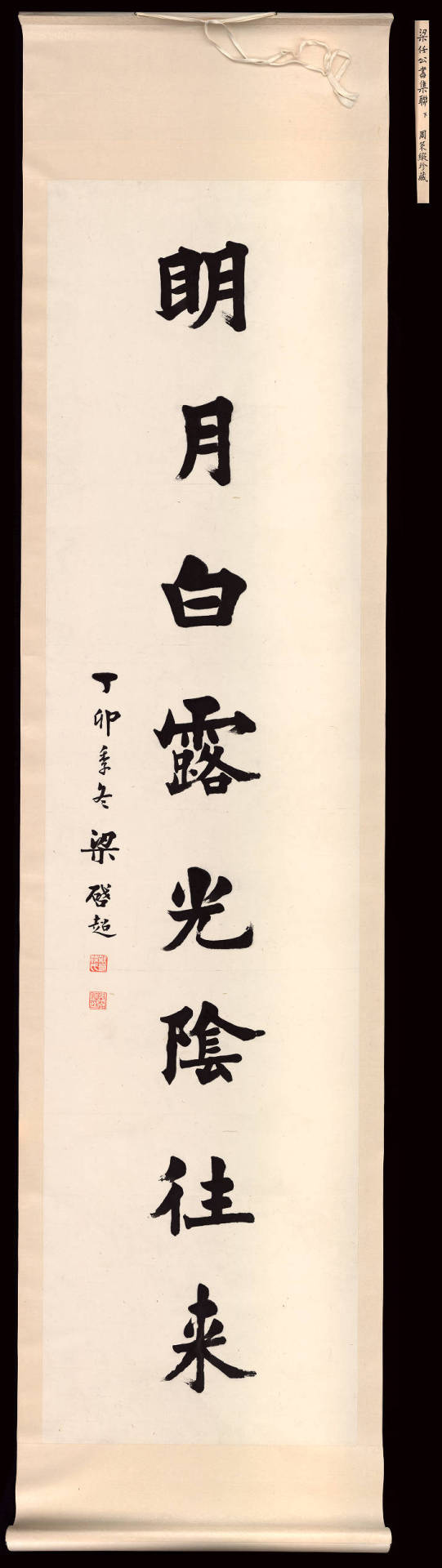

Figure 1. Liang Qichao’s Portrait

Graduate Research:

Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 3

This week I am featuring a two-scroll couplet (figures 2 & 3) by the Chinese politician and master calligrapher Liang Qichao (1873-1929, see Figure 1). The couplet was mounted around 80 years ago, and is still in great condition. It is also one of the largest couplets in our Zhou Cezong Collection. Liang was an eminent calligrapher in modern Chinese history. For him, an important element of the arts was to express one’s disposition and personality, which was indeed resonant with his political principles. The characters were created in a sublime and fastidious fashion with evenly-divided space, which were the embodiments of Chinese standard writings, symbolizing his upright personality. Plus, in the center of a few characters, there were some barely visible X-shaped creases to help him organize his strokes along the axis and diagonal. This tiny detail is also the telling evidence of Liang’s rigor and thoughtfulness.

During the summer 1903, Liang Qichao, the second leading figure in Hundred Days’ Reform (1898), met U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of State John Hay in Washington. At that time, Liang was a wanted fugitive of the Qing court and by this time had spent five years in exile. During their tete-a-tete, John Hay prophesied that China was destined to be a great power, which has come to fruition in the past few years. It is important to note that John Hay’s clairvoyance was not ungrounded; instead, it was based on, at least partially, the unremitting efforts from Liang and his followers.

Before the Hundred Days’ Reform, Liang fervently promulgated the influence of Kang Youwei (1858-1927) in Shiwubao (Times News). However, after the reform was aborted, he developed a relationship with the revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen and became acutely aware of the importance of democratization, and became the chief spokesman for the constitutionalists. Therefore, when Kang was still engaged in saving the monarchy, Liang publicly asked him to retire. In only a few short years, Liang made a radical turn-about by converting from Kang’s staunch acolyte to a vehement dissident. This kind of ideological reversal became a common feature of Liang’s political life. When asked about this predilection for change, he said “these turn-abouts were not driven by any personal interest or impetuosity; instead, they were always coherent with my ideology to be a patriot and save my country.” According to Chinese history scholar Joseph Levenson, Liang’s shifting positions can be explained as fluid adjustments to ever-changing external situations based on his own fixed internal conviction. Thus, Liang could be seen as a political iconoclast who refused to comply with convention, and followed his own disposition and choice.

On March 1927, in the same year that this couplet was produced, Liang’s mentor Kang passed away; later in June, Liang’s soul mate Wang Guowei (1877-1927) drowned himself in the Summer Palace. Two years later, Liang himself was dead at the age of 55. The text of the couplet reads: “spring orchids and autumn chrysanthemums will keep their essence in perpetuity. However, our life is just like the bright moon and the white dew, which will vanish in a trice,” and may reflect his lamentation at the death of his boon companions.

Figure 2. UWM Special Collection (cs 000008a): the first couplet

Figure 3. UWM Special Collection (cs 000008b): the second couplet

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher

#graduate research#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese scrolls#Liang Qichao#Chinese politics#calligraphy#couplet#art history#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection#Jingwei

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Figure 1. Statue of Yan Xiu in Nankai school in Tianjin, China (Photo by Fanghong).

Figure 2. Calligraphic couplet by Yan Xiu, UWM Special Collections (cs 000017).

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 8

This week we focus on an important Chinese calligraphic treatise and on an interesting dichotomy in Chinese art relating to the couplet shown above (Figure 2) by noted Chinese educator and co-founder of Nankai University Yan Xiu (1860-1929, Figure 1) from our Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work. The couplet reads:

A copy of Wang Xizhi’s “Huang Ting Jing” (a copy of Wang’s calligraphic writing) is what I like to emulate. “Biyu”(an ancient musical composition)-like melody is what I usually play in my place. I strive to read various books including very valuable imperial collection. Orthodoxy of Confucianism is the principle I inherit and strictly follow.

In the fourth century, Wei Shuo (272-349), the teacher of Wang Xizhi (303-361, the most famous calligrapher in Chinese history), illuminated seven seminal strokes of calligraphy (Figure 3, see from right to left) in her treatise Diagram of the Battle Array of Brush (translated also as The Picture of Ink Brush):

First Stroke 一 ---Like a line of clouds stretching a thousand miles, indistinct yet tangible.

Second Stroke 、---Like a rock falling from a peak, pounding yet crumbling.

Third Stroke丿---Clean-cut like (the horn of) a rhinoceros and (the tusk of ) an elephant.

Fourth Stroke ㇂---A shot from a crossbow which has one hundred Jun (15 kilograms) in strength.

Fifth Stroke ∣ ---Old vine ten thousand years of age.

Sixth Stroke ㇏--- Breaking wave and rumbling thunder.

Seventh Stroke 𠃌 --- Sinew and joints of a strong crossbow.

Figure 3. Wei Shuo’s Diagram of the Battle Array of Brush, from Lucy Driscoll and Kenji Toda, Chinese Calligraphy (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1935), pp. 41-46.

The brushstrokes from Yan Xiu’s couplet align with the key features of these seven key strokes. They look impregnable and sublime, as if representing troops arrayed for battle, generating an aura of power and uprightness.

Yan’s brush style seems influenced by that of Huang Tingjian (1045-1105), as can be seen in Huang’s Scroll for Zhang Datong. For instance, for the character “書,” Yan (Figure 4: Left) and Huang (Figure 4: Right) commonly conveyed a sense of foreboding compactness and deliberate poise. This common feature indicates both of them had a great understanding of the ancient artistic principles. However, there is one striking difference between these two figures; and this difference reveals an intriguing dichotomy in Chinese art.

Figure 4. Left: Yan’s character from Figure 2; Right: Huang Tingjian’s Scroll for Zhang Datong

As one of the most celebrated calligraphers of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Huang disliked the formality and sophistication of some ancient arts. Instead, he stressed asymmetry, irregularity, and spontaneity in his creation while maintaining a dynamic equilibrium for the whole. In Figure 4 (Right), the first horizontal stroke (as well as the top of the central vertical stroke) breaks the balance of the composition by pushing the character to the top right. Next, the intensity of the second horizontal stroke pulls the dynamism of the word back to the left. The third and fifth horizontal strokes also contribute to this counterbalance by the alterations of their width and angle. Finally, the slim vertical line down to the left is overshadowed by the powerful counterpart to the right, thereby moving the axis to the right again. Here, Huang created an S curvature throughout the word, which is analogous to the contrapposto effect in Michelangelo’s statue of David---although the individual parts lean to different directions, the overall structure maintains an equilibrium. On the contrary, for Yan’s work in Figure 4 (Left), the composition and strokes seem to be uniform and sophisticated with very few contrasting and complementary elements. Bordering on rigidity, his brush was likely to be premediated in a careful plan; and he was faithful in carrying out this plan.

Chinese landscape painting has also undergone a similar dichotomy between dramatic exaggeration and rigid unification. For example, in his famous painting Early Spring, one of the most acclaimed Chinese artists Guo Xi (1020-1090) adopted the same curvilinear undulation and dramatic interpenetration. The landscape, which is depicted by the thickening-and-thinning strokes, emerges and recedes in a dragon-shape composition, indicating not only the rich variety of the scenes, but also a vison of the cosmos and the tension of psychology.

However, art by an orthodox painter, such as Wang Shimin (1592-1680) in the early Qing court, displays a kind of monotony and rigidity. In his The Serenity and Joviality on Pine Cliff, Wang applied similar textual strokes and stippled effect to the whole composition, without any interplay between disequilibrium and equilibrium.

The difference between Song Dynasty vividness and Qing’s rigidity is largely due to political factors. The five capable and enlightened emperors of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) helped to establish an unrivaled cultural and artistic renaissance. By contrast, in Qing Dynasty (1636-1912), under the tight grip of ideology, any aesthetic deviation from the central principles would be regarded as revolution. Therefore, artists had to pander to the tastes of the emperor by following the specific formulas. Gradually, they got themselves into a rut, as a deadening pall would descend upon their creativities. Yan was a high official in the Qing court, so he was inevitably the victim of this stultifying uniformity.

Yan was the most important figure in the modernization of Chinese education, and is regarded as the founding father of Nankai University. In 1902, his trip to Japan culminated in numerous constructions of modern schools (almost at the same time Zhang Jian, whom I discussed in a previous post, promoted education in the southern part of China, so they won laurels as “North Yan, South Zhang”). In 1905, under Yan’s suggestion, the court terminated the imperial examinations, and Yan became the first vice-minister of the Ministry of Education. Under his leadership, the modern Chinese educational system was established. He was assisted by Zhang Yuanji, who I also discussed in a previous post, and Luo Zhenyu, whose couplet scroll in Oracle Bone script is also preserved in our Zhou Cezong Collection.

In 1920, Nankai University student Zhou Enlai (1898-1976, the first premier of the People’s Republic of China) was arrested by the government and later was dismissed from the school for his leadership in a student campaign. Yan created an ad hoc scholarship, and sent Zhou to study in Europe. When he learned that Zhou had become a Communist member in France, he still continued to support the latter’s education because he said “literati should be allowed to have diverse ambitions.”

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Yan Xiu#Chinese scrolls#Chinese calligraphy#calligraphy#art history#Wei Shuo#Wang Xizhi#couplet#Diagram of the Battle Array of Brush#The Picture of Ink Brush#Huang Tingjian#Zhou Cezong Collection#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Jingwei

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Figure 1: UWM Special Collections (cs 000049)

Figure 2: Zhang Yuanji’s Portrait

Figure 3: Detail from Figure 1.

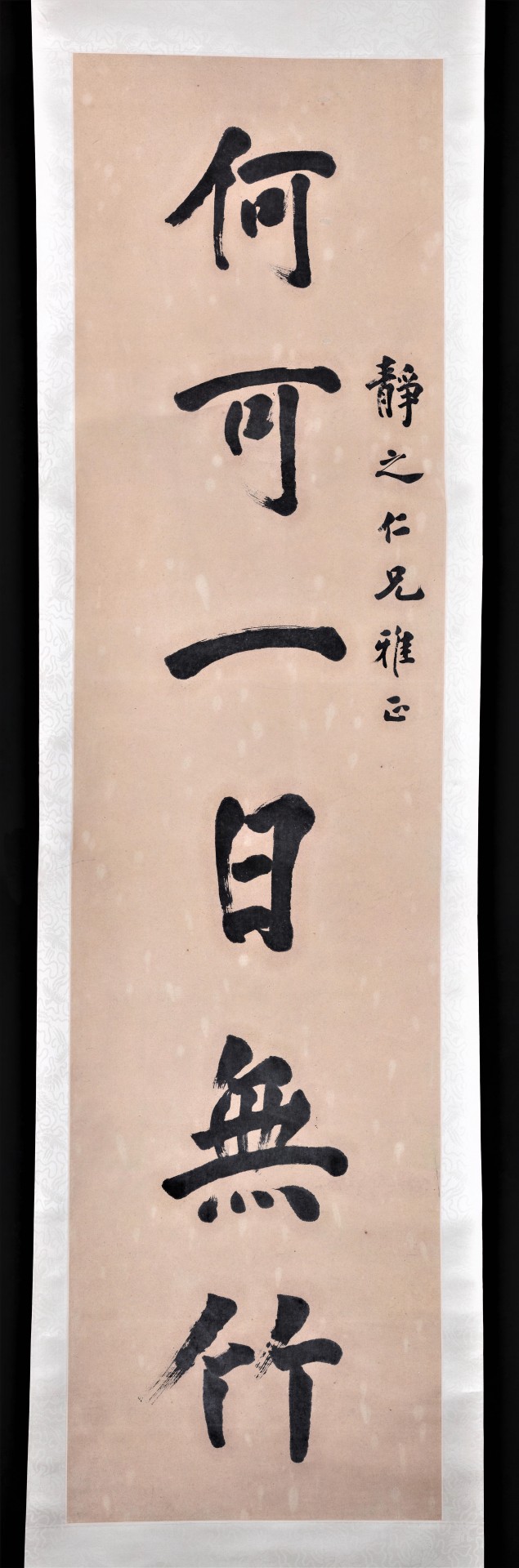

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work

Earlier I discussed the calligraphy of Chinese political reformer Kang Youwei. Today I present a couplet by Kang’s reformer colleague Zhang Yuanji (1867-1959, see Figure 2 ). The content of the couplet shown in Figure 1 reads, “how can I spend my day without the bamboos; and how regrettable that I cannot have ten years to study.” This is the lifelong dream for most traditional Chinese hermits and scholars---bamboo indicates the seclusive retirement and studying is the great enjoyment of their lives. The author Zhang Yuanji, who was the most prominent publisher in Chinese modern history, created this couplet in 1946. As the manager of The Commercial Press, he worked hard in his publishing career to develop educational material for the Chinese people. Dedicated to his publishing career, Zhang had little leisure time to enjoy seclusion, so this couplet symbolizes his ideal to be the hermit.

In 1898, Zhang was a leading figure of Hundred Days’ Reform (June 11 to September 22, 1898). During his private meetings with the Guang Xu Emperor, he expressed his passion to promote education reform, and introduce western culture to China. After the Hundred Days’ Reform was stymied, he transferred his political ambition to publishing. Though he was trained as a traditional Confucian scholar, he had a great liberal mind to embrace new ideas--- by publishing modern textbooks for different levels of education, and translating thousands of academic and literary works from oversees, he was committed to parlaying his publishing success into the rejuvenation and modernization of China. Under his leadership, his company The Commercial Press became the most well-known publishing company in the modern Chinese history.

The ink tonality of this couplet is pale. Its surface is covered with tiny spots, perhaps mildew, which diminished the luster of the ink (see Figure 3). The mildew might be a result of improper preservation, such as leaving the work in a damp corner, or hanging it in a humid environment.

This couplet is from the UWM Tse-Tsung Chow Collection (Zhou Cezong, 1916-2007) of Chinese scroll and fan work.

View more posts from the Tse-Tsung Chow Collection.

-- Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher

#graduate research#Zhang Yuanji#Chinese scrolls#Chinese calligraphy#calligraphy#art history#couplet#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection#Jingwei

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 5

Zhang Jian (1853-1926) was one of the most successful entrepreneurs in modern Chinese history, as well as an eminent leader in constitutional government and Chinese modernization. In a calligraphic scroll from our Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work, Zhang, also an accomplished calligrapher, cites an anecdote from one of Song Dynasty scholar-official Su Dongpo's literary works:

After reading [2nd-century BCE musician and poet] Sima Xiangru’s “Da Ren Fu,” Emperor Wu in West-Han dynasty feels like a deity who can walk on the cloud and travel in the universe. Recent scholars believe themselves to be as talented as Sima Xiangru, so they emulate his works with alacrity. Sima has died and can't make any comment for these emulations. However, I believe these works are just boring and may make audiences feel sleepy and fall out of bed---they could hardly have experience to walk on the cloud.

This calligraphy was dedicated to Yiqing, who followed Zhang in philanthropic activities during the final days of his life. The cursive calligraphic style derives from early Tang Dynasty calligrapher Sun Guoting’s A Narrative on Calligraphy, pulsating with fluidity, confidence, and spontaneity. Influenced by a passion to learn the ancient stele of the late Qing dynasty, however, Zhang also imbued this work with a strong sense of sublimity and equanimity. The integration of these opposing styles can also be seen in his political ambition.

Zhang was the Principal Graduate (the highest-ranking student in the national official examination) in 1894. In the next year, he helped Kang Youwei (1858-1927), whom I posted about earlier, to initiate the Society for Study of National Strengthening in Shanghai. However, he was relatively conservative in his political stance. Therefore, when he knew Kang and Liang Qichao (1873-1929), whom I also posted about, were in the full swing during the Hundred Days’ Reform, he indicated that the reform might have unpredictable consequences and he cautioned Kang and Liang, “don’t act foolhardily.” Being disillusioned by the corruption of the court, he decided to go back to his hometown to create businesses and invest in education. During his life, he set up more than twenty enterprises and three-hundred-and-seventy schools in China. He also founded Nantong Museum in 1905, the first museum in Mainland China. The bust of Zhang Jian shown here stands outside Nantong Museum.

As a businessman, Zhang needed a peaceful environment for his companies, so he did not want to see revolutions. Citing Japanese constitutionalism practiced since the Meiji Reform, he asserted that only constitutionalism could save China from degradation. Therefore, integrating monarchical beliefs and democratic principles became his political ambition, and he determined to transform China into a modern society. Nevertheless, after political unrest, in 1912 Zhang was designated to write the Edict of Abdication for Puyi, the last emperor of China. When the new temporary government was founded, he used his property as the mortgage to stabilize the financial situation of the country.

During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s, Zhang’s tomb was opened and destroyed by the Red Guard. Only one hat, one pair of glasses, one fan, and one small box with the his tooth and hair were found. This “booty” seems so meager in view of his extraordinary prestige and achievements. Based on his accomplishments, he is often honored as one of the “creators of the Republic of China.”

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese scrolls#Zhang Jian#Chinese politics#Chinese political reforms#Su Dongpo#Chinese history#art history#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection#Jingwei

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Figure 2. UWM Special Collections (cs000102)

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 4

This week we focus on a calligraphic scroll from our collection (Figure 2) by the Chinese poet and political reformer Chen Sanli (1853-1937, Figure 1). From the middle of the Qing Dynasty, scholars had a growing interest in the study of ancient stele inscriptions, especially those from the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534). With the obvious trace of chiseling, these steles are characterized by archaism and solemnity. The style of Chen’s hanging scroll, which might be derived from a particular stele shown in Figure 3, was rendered with rigor and solemnity, exhibiting a strong expression of scholastic elegance. Nonetheless, the last vertical stroke of “别” in the first line (the eighth character) exhibits an unexpected angularity, which symbolizes Chen’s ambition to break the precedents and express his own style.

Chen was one of the most eminent Chinese reformers of the nineteenth century. In 1895, Chen’s father Chen Baozhen was promoted to governor of Hunan Province. Afterward, father and son worked together to press a thoroughgoing program of reform. In order to do so, they invited some reform-minded literati such like Jiang Biao (1860-1899) and Liang Qichao (1873-1929) to join in their campaign. Their provincial success won accolades in the nation, thereby encouraging the emperor to implement the reforms nationwide.

However, from late 1897 to early 1898, the reform movement grew increasingly radical. Liang denounced the government openly and prepared Hunan’s independence. In addition, the Western ideals of egalitarianism which the reformers endorsed were contradictory to the core values of the local gentry. Finally, the reformers were gradually expelled. On September 20, 1898, the Empress Dowager (1835-1908) staged a coup against the pro-reform Guang Xu Emperor (1875-1908) and his supporters after the Hundred Days’ Reform. Kang Youwei (1858-1927) and Liang were forced in exile; and Chen and his father were “dismissed forever.”

In fact, Chen was a moderate conservative. What he preferred was a gradual reformation, rather than Kang’s and Liang’s fanatical extremism. After he was dismissed, Chen found his solace in Chinese poetry; and became the spearhead of the Tong-Guang Poetic Style (named after two emperors, Tong Zhi (1856-1875) and Guang Xu). His poetic taste was similar to his moderate political stance---while trying to create uniqueness for his style, he neutralized it with the emulation of the traditional symbolism from some ancient masters. In our UWM collection, Chen’s scroll first follows the common practice in many Song poems to narrate scenery:

After snow stops, it immediately starts drizzling. Living in a desolate place is like settling in another world. The cloud fights with the interchangeable coldness and warmness; and the hill witnesses the contrasting beauty and ungainliness. A rustling noise of dry leaves serves as a cue telling me there are visitors. Water-sounds of a gurgling stream triggers me to play Qin (an ancient Chinese stringed instrument).

But he then finalizes the poem with, “Rains dampen the wings of a solitary eagle, but it will still soar to the twilight,” expressing a bittersweet poignance -- though he had great ambition to make some differences, history didn’t give him ample time to pursue his dream.

Figure 3. Northern Wei stele

View more posts from the Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese scrolls#Chen Sanli#Chinese politics#Chinese poetry#Tong-Guang Poetry#Hundred Days' Reform#Chinese stele#Northern Wei stele#art history#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection#Zhou Cezong Collection#Jingwei

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Chinese Scroll Caturday

This Caturday we present an original Chinese scroll painting of five tigers in a bamboo ravine from the collection of the late UW-Madison professor emeritus of East Asian Languages and Literature Tse-Tsung Chow (Zhou Cezong). The painting was produced in 1930 by the noted Chinese Republic artist Zhang Shanzi (1882-1940). Zhang’s specialties were landscapes, flowers, birds, wild animals, and most especially tigers -- so much so, that he used the pseudonym Tiger Man.

This image is from our digital collection “The Tse-Tsung Chow Collection of Chinese Scrolls and Fan Paintings,” digitized from the original in our holdings of Dr. Chow’s collection of over 120 scroll and fan works.

#Caturday#tigers#Chinese scroll paintings#Tse-Tsung Chow#Zhang Shanzi#digital collections#paintings#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection

191 notes

·

View notes