#accepting incontinence is also a two-way street; it will help you have compassion for others with incontinence

Text

the replies on that post make me so sad. you can have issues with unsanitary things and still learn and accept very simple facts about bodily functions. you should be in-touch with your body, even with the ‘gross’ stuff it does.

#i'm not trying to be insensitive to anyone with phobias here but#this is your own body we're talking about#it really does do you good to pay attention to things like severe cramps that could be bowel obstructions#accepting incontinence is also a two-way street; it will help you have compassion for others with incontinence#so they don't have to feel constant shame and guilt about it#like please just think about this and stew on it for a while or something#the sanitizing of our culture and media re: basic bodily awareness is sad

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

OPEN M continues to serve Akron, Summit County with free medical care, food programs

New Post has been published on https://depression-md.com/open-m-continues-to-serve-akron-summit-county-with-free-medical-care-food-programs/

OPEN M continues to serve Akron, Summit County with free medical care, food programs

Jackie Chandler has had medical insurance off and on, depending on her jobs over the years.

So when she hasn’t had insurance, she has relied on the free medical care for her high blood pressure and other ailments at Akron’s OPEN M, a Christian-based ministry and nonprofit. Chandler has also used the food pantry services.

On a recent visit to the medical clinic at OPEN M in Akron’s Summit Lake area, Chandler, 70, was so weak from severe pain in her lower back and lack of appetite that the physician who saw her that evening told her she needed to get to the emergency room. But Chandler was too weak to drive herself.

So Dr. Joseph Rinaldi, a cardiologist at Western Reserve Hospital who volunteers once a month at the clinic, drove Chandler to the emergency room.

“I’m just amazed,” said Chandler recently from her hospital room at Summa Health’s Akron City Hospital, where she was on her sixth day treated for a severe urinary tract infection and severe dehydration. “I was in awe in the whole situation.”

OPEN M Executive Director Christine Curry said it is highly unusual for one of the physicians to drive a patient to the hospital, but shows the level of care and compassion of the professionals who come and volunteer their time.

“It’s definitely atypical, however Dr. Rinaldi is extremely dedicated to the patients at Open M. They truly love him and appreciate that one of the best cardiologists in the region is here. For someone with his reputation to show that kind of care and due diligence speaks volume to what we have here,” Curry said.

Rinaldi said it was the first time in his career he’s ever driven a patient to the hospital, though acknowledged he has wheeled a patient or two to the Western Reserve Hospital emergency room from his office in the hospital.

“She came in and she was obviously sick. I was worried she was dehydrated and was having trouble walking,” said Rinaldi. “She really probably shouldn’t have driven herself to the clinic let alone to the emergency room, which is where I thought she should go.”

Rinaldi said the patients seen at the OPEN M medical clinic don’t have insurance so “the last thing I wanted for her was to get a bill for an ambulance. It was near the end of the clinic. it was on my way home. It really wasn’t a big deal.”

Rinaldi wheeled Chandler into the Summa Emergency room and gave the doctors there a little history before he left. He was suspicious she had a urinary tract infection and nothing related to her heart, which is his specialty. Rinaldi was at OPEN M that night for his shift seeing all patients, not just cardiology patients.

Helping the community

The medical clinic, which is open Monday through Thursday by appointment and serves as a patient’s primary care practice, is just one of the free programs offered by OPEN M, which has been serving the greater Akron community for 53 years. It was formed as Opportunity Parish Ecumenical Neighborhood Ministry in 1968 by four churches, and Curry said it has since received supported from additional churches, foundations, nonprofits, corporate partners and thousands of volunteers.

All programs are free and income eligible. To register for one of 10 food service programs offered by OPEN M, contact United Way of Summit and Medina County’s 2-1-1 service (dial 2-1-1 or 330-376–6660). To check eligibility for OPEN M’s medical clinic, call 330-434-0110.

OPEN M serves the Summit Lake community around its headquarters on Prince Street, but clients for the medical clinic and food services come from all over Summit County, Curry said.

A total of 40% percent of the clinic’s active patients are from the Summit Lake neighborhood and the other 60% are from greater Akron and Summit County. Among patients, 43% are white, 42% are black/brown and the rest identify as “other” or are unidentified, Curry said.

“There’s a misnomer out there about uninsured folks and what they look like and people are totally inaccurate,” said Curry, who has been executive director since last year. “Being uninsured is an equal opportunity thing and the world needs to step up and do something about it in this country. We are more than happy to be the go-to place and the only true free clinic in Summit County. We are truly free. We don’t take Medicaid. Our prescriptions are all free. Last year in 2020, we gave out more than $1.5 million in free prescriptions.”

For OPEN M’s food services, 7% of the households were from the Summit Lake neighborhood, 92% were from the rest of Summit County and 1% from outside the county, said Curry. Last year, OPEN M’s food outreach programs gave out $1.25 million worth of food to nearly 14,000 households or more than 37,000 individuals.

Chandler said the medical clinic and food pantry, where she has gotten food staples from OPEN M, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, has been extremely helpful. The physicians helped her get her high blood pressure under control and she has been able to see specialists like chiropractors and acupuncturists during special clinics.

“It was enormously helpful,” said Chandler, who is sad since she will be transitioning to Medicare and will not be able to utilize the medical clinic but will still use the food services. “They supplied any needs I had whatsoever, including the food pantry. They’re just awesome.”

Food insecurity among senior citizens is on the increase, Curry said, noting that more than 4,000 in Summit County received assistance from OPEN M in 2020.

Serving during the pandemic

OPEN M’s services also did not stop during the COVID-19 pandemic, said Julie Carneal, the organization’s facilities and food services manager.

The medical clinic closed to in-person during the height of the pandemic, but switched to telehealth appointments and continued to dispense patient’s needed medications, Interim Manager Tammy Hicks said. It is now open again to in-person appointments Monday through Thursday, with specialty clinics about nine to 10 times a month.

The food services programs of OPEN M also didn’t stop during the pandemic, when need was great, Carneal said.

The food pantry, which offers food staples once a month with a referral “was one of the ones that never shut down. All of our employees, even though their programs shut down, they worked through the pantry. We weren’t allowed to have volunteers in here [at the height of the pandemic], so we kept it going. We never missed any programs at all,” said Carneal.

OPEN M has or participates in 10 different programs for food distribution, including a new partnership with Door Dash to deliver pantry-type food to shut-ins and the blessing bags, which offer canned foods to get people by overnight and hot meals, offered daily the last two months of the week. There is even available donated dog and cat food from the Humane Society.

OPEN M moved all of its food pickups to a drive-thru system during the pandemic and has areas for those walking up; it will continue that method through the winter, said Carneal,

“We found it is a lot more efficient and less hassle for people standing for any length of time. If they don’t have a car, they come through and stay on benches until we’re ready to serve,” she said.

New stand-alone dental clinic

OPEN M also has a new stand-alone dental clinic named The Harry and Fran Donovan Dental Clinic. OPEN M has had volunteer dentists seeing patients through its medical clinic but the new stand-alone dental clinic with multiple bays offers more space for the specific needs, Curry said. The clinic started taking patients in February.

Curry is looking to hire a dentist and hygienist for 30 hours a month each to work with the volunteer dentists to serve more people.

Until the hires are made, for now, the 450 active OPEN M dental patients are the only ones who can be seen in the clinic, Curry said.

Summit County Councilwoman Veronica Sims, who grew up in the Summit Lake area, volunteered at OPEN M as a teen and whose county ward covers the area, praised the organization for serving its neighborhood and beyond.

“OPEN M has inserted itself in the neighborhood. It’s not something happening as an offshoot. It’s integrally a part of this community,” Sims said.

“I hope through this whole pandemic, in the work that OPEN M has continued to do, that we start to re-evaluate what public health looks like and where does public health meet the community in a real way — so that we’re not doing this kind of recognizant kind of work trying to mobilize within the community when we have these crises,” she said.

Beacon Journal staff reporter Betty Lin-Fisher can be reached at 330-996-3724 or [email protected]. Follow her @blinfisherABJ on Twitter or www.facebook.com/BettyLinFisherABJ. To see her most recent stories and columns, go to www.tinyurl.com/bettylinfisher.

How you can help

• OPEN M can accept donated prescriptions, but only if they are still sealed and not expired. It will also take incontinence and wound care supplies. It cannot accept medical supplies like walkers or wheelchairs.

• To volunteer, make a monetary donation or find out other ways to help, go to www.openm.org or call 330-434-0110

Source link

0 notes

Photo

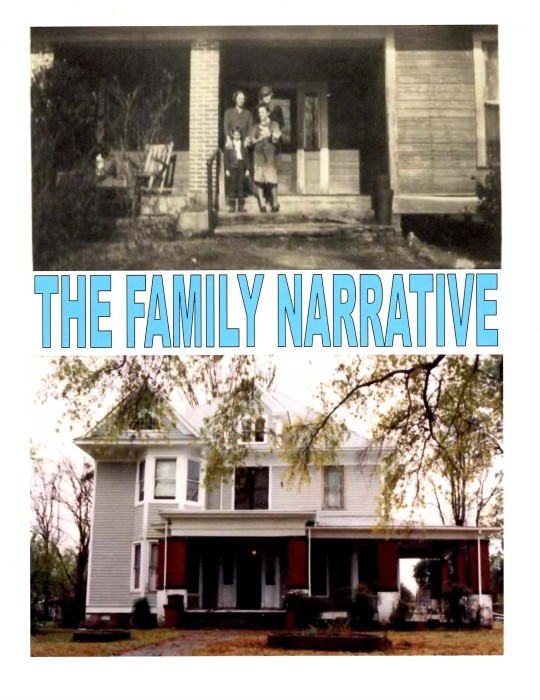

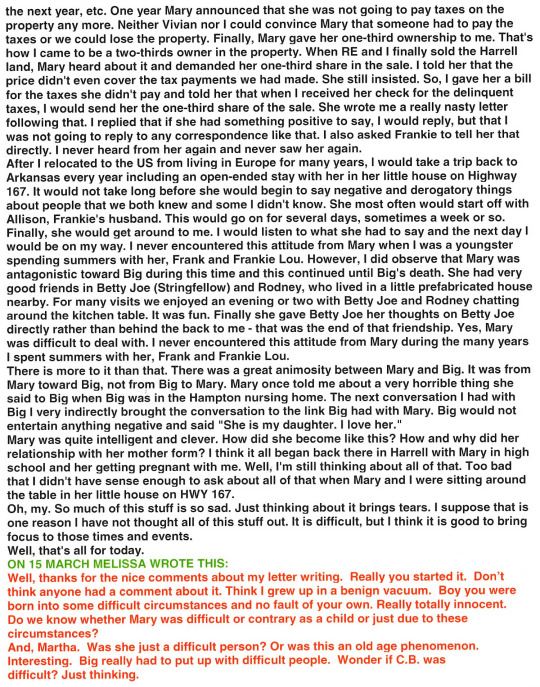

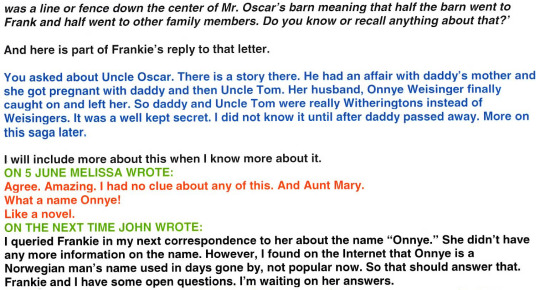

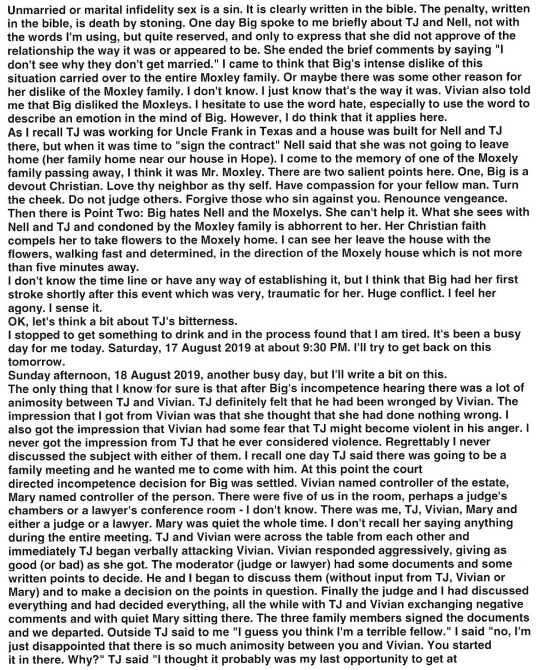

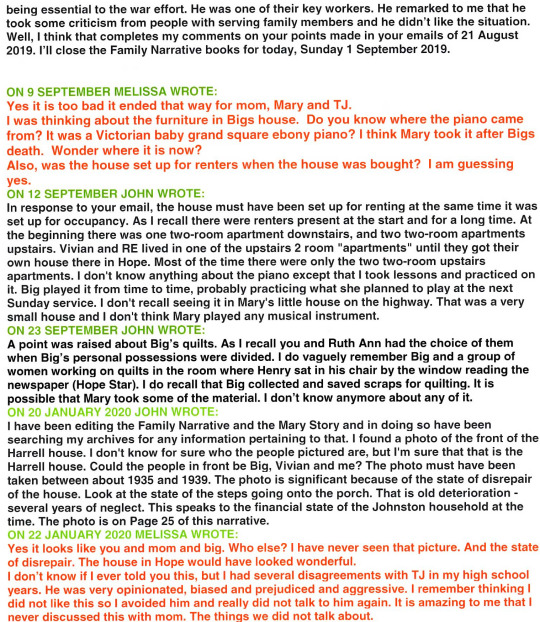

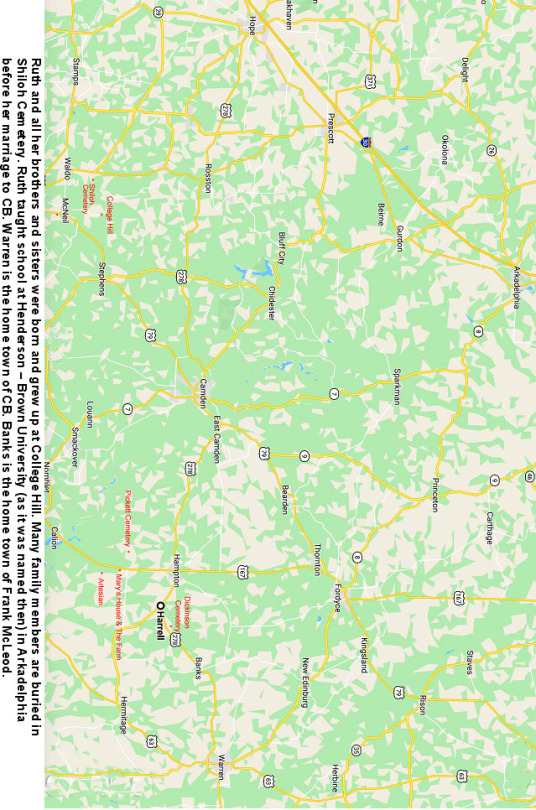

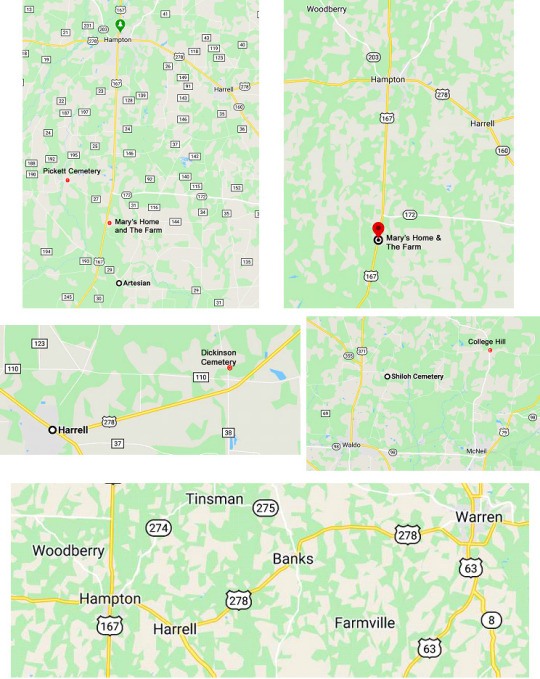

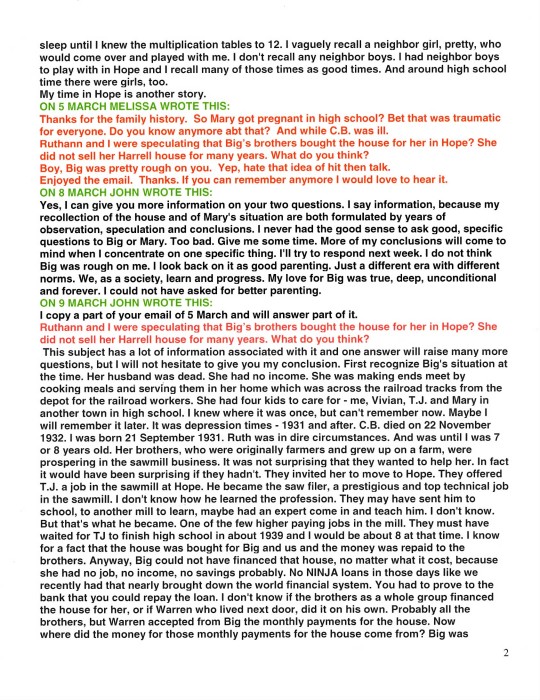

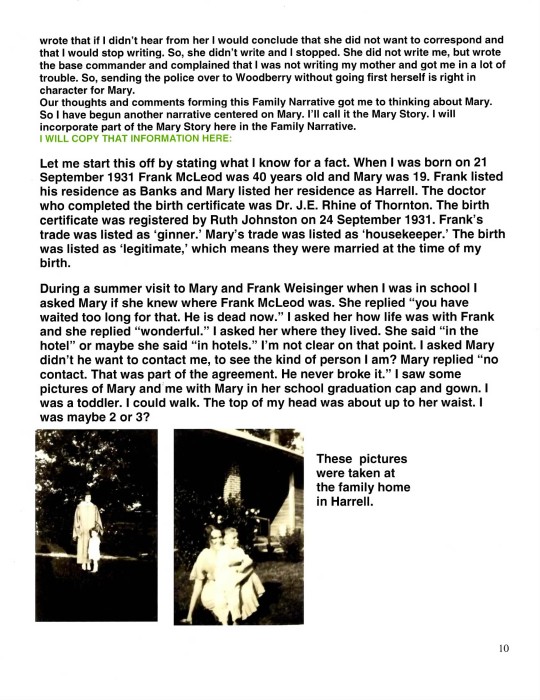

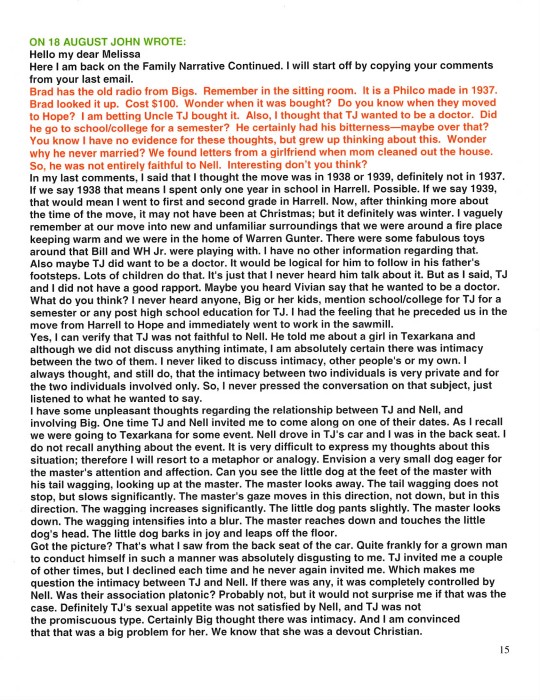

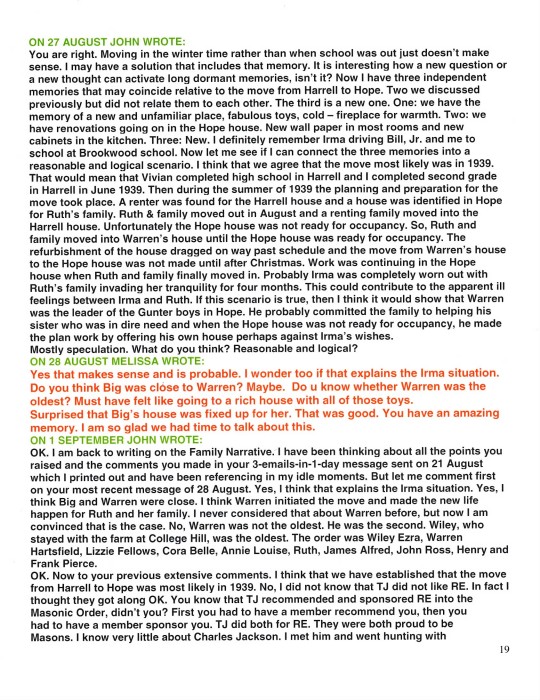

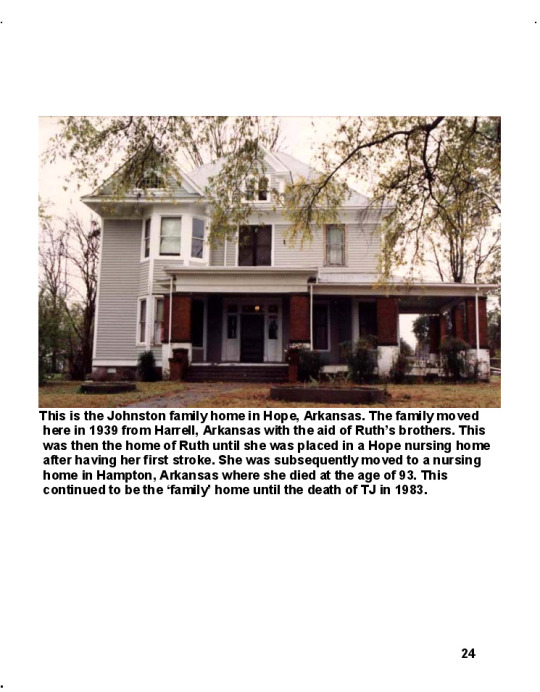

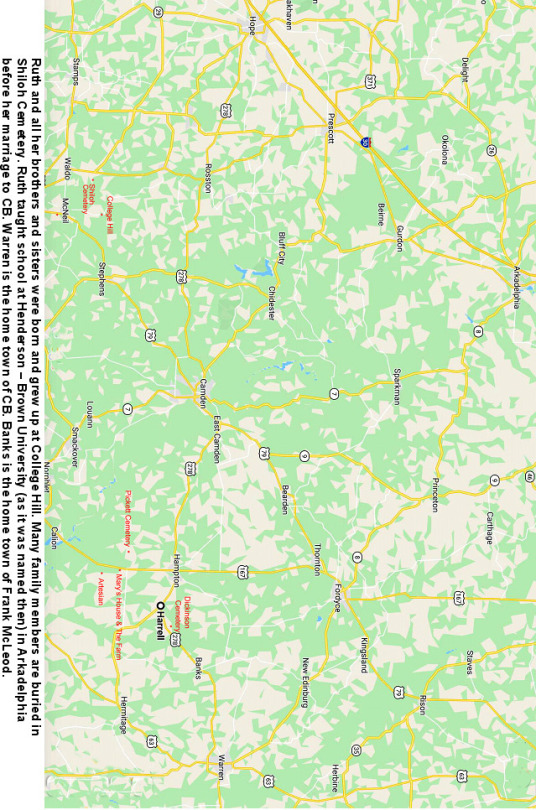

This is the Johnston family home in Hope, Arkansas. The family moved here in 1939 with the aid of Ruth’s brothers. This was then the home of Ruth until she was placed in a Hope nursing home after having her first stroke. She was subsequently moved to a nursing home in Hampton, Arkansas where she died at the age of 93. This continued to be the ‘family’ home until the death of TJ in 1983.

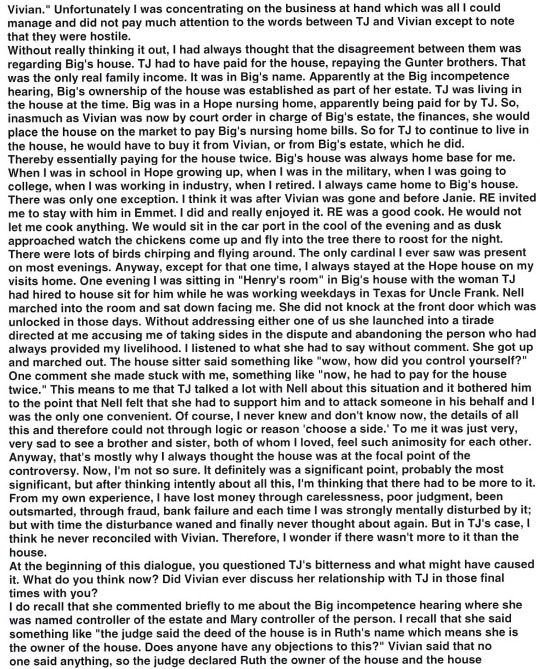

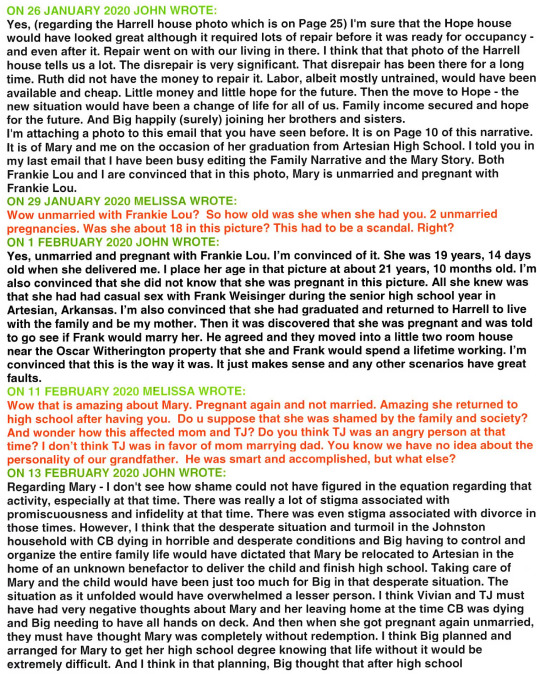

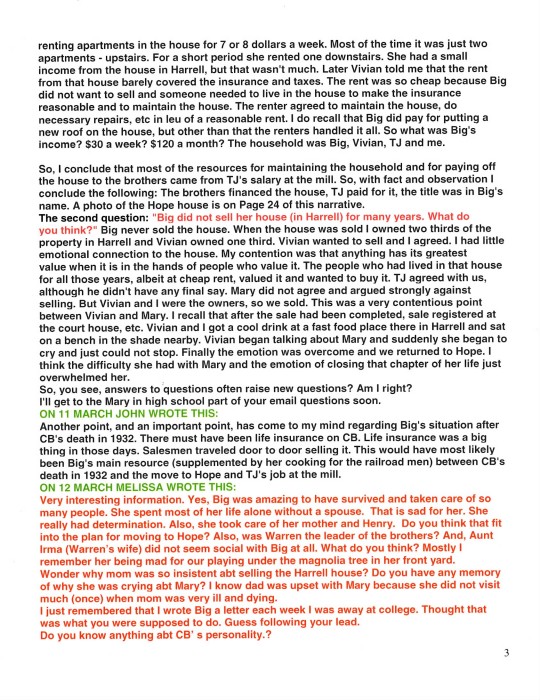

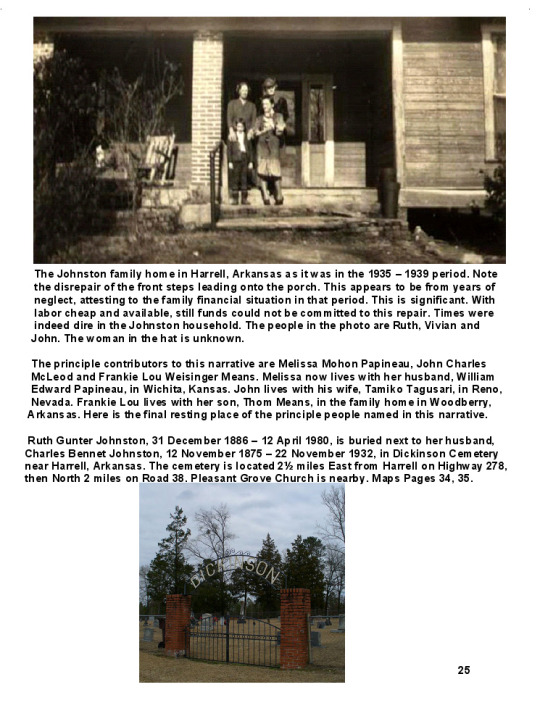

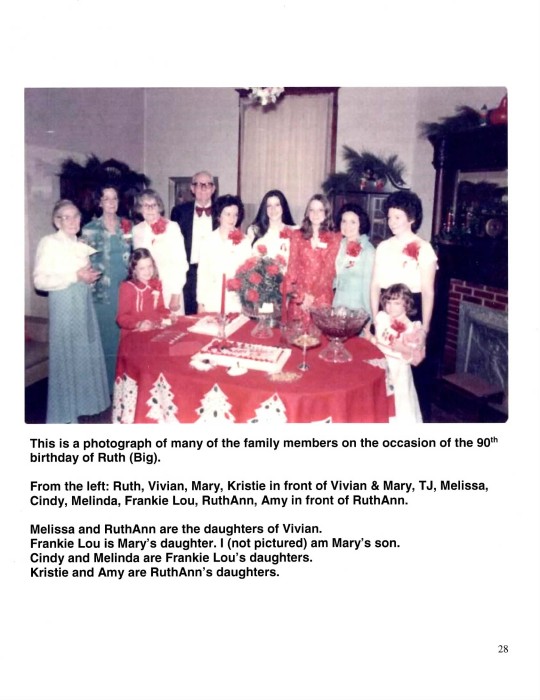

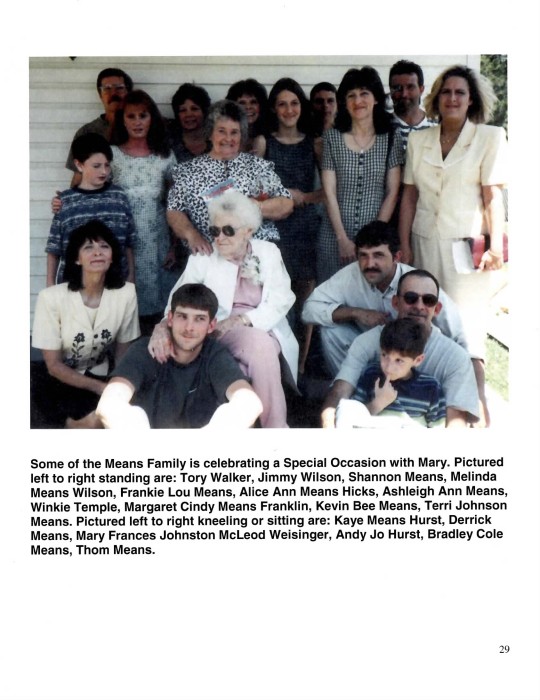

The Johnston family home in Harrell, Arkansas as it was in the 1935 - 1939 period. Note the disrepair of the front steps leading onto the porch. This appears to be from years of neglect, attesting to the family financial situation in that period. This is significant. With labor cheap and available, still funds could not be committed to this repair. Times were indeed dire in the Johnston household. The people in the photo are Ruth, Vivian and John. The woman in the hat is unknown.

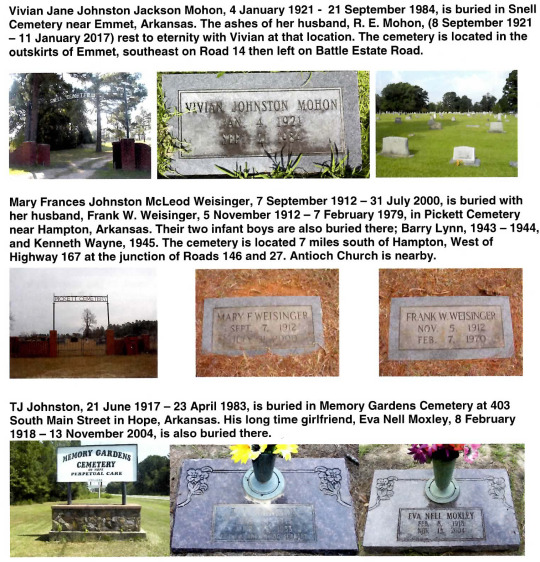

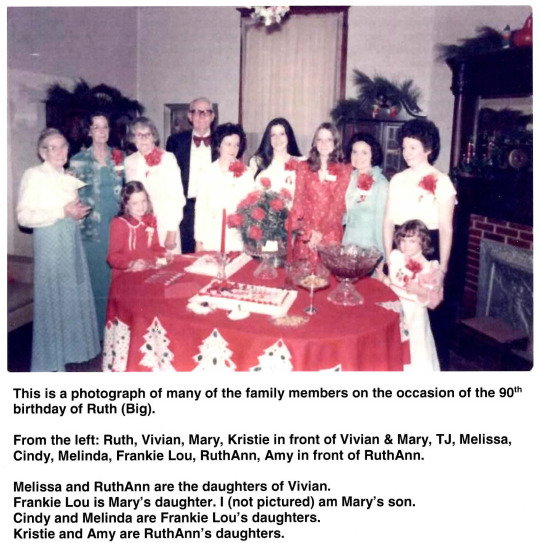

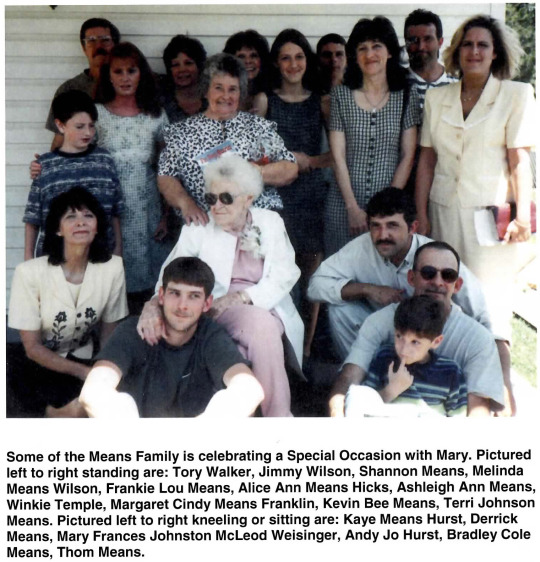

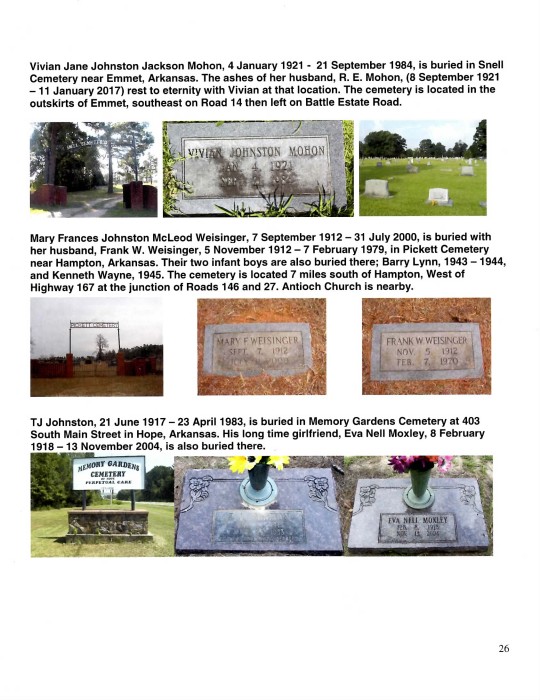

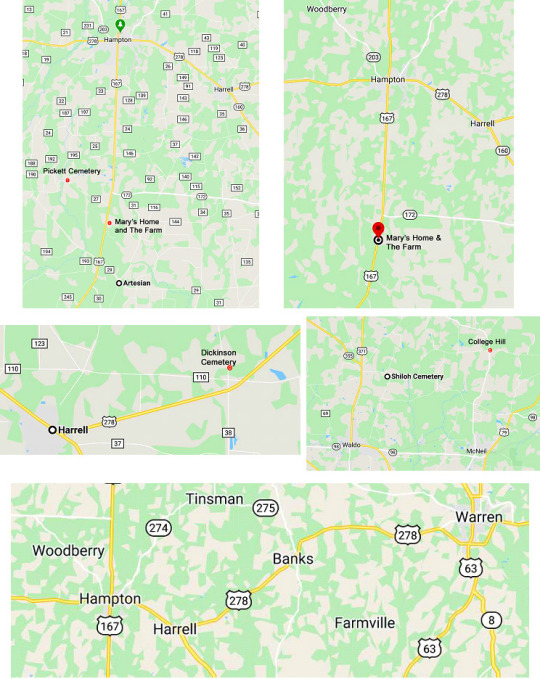

The principle contributors to this narrative are Melissa Mohon Papineau, John Charles McLeod and Frankie Lou Weisinger Means. Melissa now lives with her husband, William Edward Papineau, in Wichita, Kansas. John lives with his wife, Tamiko Tagusari, in Reno, Nevada. Frankie Lou lives with her son, Thom Means, in the family home in Woodberry, Arkansas. Here is the final resting place of the principle people named in this narrative.

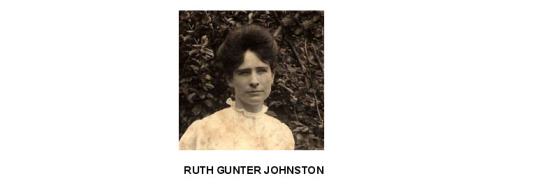

Ruth Gunter Johnston, 31 December 1886 - 12 April 1980, is buried next to her husband, Charles Bennet Johnston, 12 November 1875 - 22 November 1932, in Dickinson Cemetery near Harrell, Arkansas. The cemetery is located 2 1/2 miles East from Harrell on Highway 278, then North 2 miles on Road 38. Pleasant Grove Church is nearby.

TJ Johnston retired from sawmill work in 1982 at age 65. He was living in the Hope house at 707 East Division Street. He had always done most of the work around the house and very seldom hired outside help. The rain gutters in the house required cleaning. TJ failed to accept that he was now elderly and with less coordination, balance and strength. He undertook this task, one he had always done himself. He fell from the roof, injuring himself and was confined to the hospital. He chose not to go to the care of our family doctor, Dr. Jim McKinsey, in the Branch General Hospital where Vivian was the Chief of Nurses; but went to another hospital instead. Vivian commented that he would not receive optimum care in the facility that he chose. While confined in the hospital he suffered a heart attack and died, ten months after retiring. He had been a smoker for most of his life. While the fall did result in severe injury, surely it was demon tobacco that took his life.

Vivian was the Chief of Nurses at Branch General Hospital. In addition to her administration tasks, she also worked in the cancer ward of the hospital. She developed a chronic cough. Dr. McKinsey, who she worked with there, kept urging her to check out the cough. Finally she made a chest X-ray. She told me “when I saw those X-rays I knew I was looking at my death warrant.” She had lung cancer. She had been a smoker most of her life and was a smoker then. She had surgery but all the cancer could not be removed. She was given six months to a year to live. In about a year the cancer returned. It was demon tobacco taking another life.

I, John McLeod, also smoked as a youngster as most people did in those days. I smoked for about ten years and finally became disgusted with the filthy habit. This was before we knew that tobacco could and most likely would kill you if you used it. Ridding myself of the demon tobacco was the most difficult thing I did in my life. I attribute a heart attack I suffered in 1999 to the demon tobacco. Today I continue life with high risk from cardio vascular disease. I wrote a blog about the demon tobacco. Create a hyperlink on your computer with the following address, click on it, and you can read the blog. If you are reading this on a computer connected to the Internet, that is a hyperlink. Just click on it. https://JohnArk.Tumblr.com/tagged/tobacco

MELISSA’S FAMILY IN 2018

From the left: Bradley Mohon Papineau, Mateus Lima, Melissa Mohon Papineau, Anne Papineau Nelson, Mikael Nelson, William Edward Papineau.

In this narrative we have briefly stated that Big cared for her dying husband in difficult circumstance in Harrell in the early 1930s and later cared for her dying mother in her home in Hope. The comments about Big’s caring for her mother, Martha Frances, are on Pages 4 and 6 of this narrative. I observed this and was amazed at Big’s skill, patience, compassion and strength both physically and mentally in dealing with what I observed as a very difficult person and difficult situation. I was just a kid at the time, but I was mature enough to recognize an extraordinary life and death event unfolding in that room and appreciate what I was seeing. But even more extraordinary and astounding as well is how deplorable conditions, devastating events, surprising and disappointing betrayals around the final two years of the life of her husband, Dr. Charles Bennett Johnston (CB), were met with such extraordinary determination, loyalty, skill, organization, perseverance, compassion, dedication, endurance, improvisation, stamina, grit, moxie – need I go on? This was indeed an extraordinary situation confronted and overcome by a more than equally extraordinary person. I want to add to what has been said about this in this narrative on Pages 2, 21, 22 and 23.

Let me start by trying to establish the situation in the Johnston household in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Vivian told me that Charles B. Johnston died of Parkinson’s disease. This disease is a progressive, untreatable, incurable nervous system disorder manifested with movement disorders, autonomic dysfunction, neuropsychiatric problems among others. The end stage of Parkinson’s is an extremely distressing situation. Today hospice takes over at that point. Family cannot provide or endure care at that point. CB probably suffered with incontinence, insomnia, dementia, hallucinations, severe posture issues with back, neck, hips and was surely bedridden. Just think of a bedridden heavy man, drooling, urinating uncontrollably, with induced diarrhea to relieve constipation, depressed, and demented. It would have been impossible for Ruth to have cared for CB alone. However inexpensive, inexperienced assistance could have been available from the black community. Surely Ruth would have expected assistance from her children – Vivian 9 or 10, TJ 13 or 14 and Mary 16 or 17. The situation in CB’s room must have been hell. And probably smelled that way, too. Hell at that point and the future very bleak. The country was in the midst of the depression with 30% of the work force unemployed. Is this the reason that Mary dropped out of school, abandoned her family and ran away with Frank McLeod? What about family loyalty, personal responsibility, conscience? What did Ruth think when her oldest daughter abandoned her in the time of most need? Yes, abandoned. Fled. That’s the way it looks to me. Yes, living with Frank would have been “wonderful” compared to the hell that existed in the Johnston household. Had she stayed with Frank, as it turned out, it would have been a blessing for Ruth. But rather than escape from it, Mary returned just in time to add to that hell and responsibility for Ruth. I was born on 21 September 1931. CB was in the last, tortured year of his life. He died on 22 November 1932. So, in summary, the situation for Ruth at the return of pregnant Mary was: caring for CB in the direst and most demanding period of his declining health, supervising untrained CB care givers, caring for two high school children, managing a household, managing the family finances, and now Ruth has to organize the care of Mary and the child and deal with Frank McLeod. Probably Mary demanded that Ruth force Frank to marry her. The fact that Frank sent her home probably meant that he would not easily agree to this. Hiring an attorney and settling the situation through the courts if required was most likely out of the question because of finances, time element, physical location and life and death responsibilities. Probably in the interests of a quick settlement of the issue, Ruth and Frank agreed upon marriage, separation, no contact, no responsibility. And Frank went happily on his way, leaving Mary angry, distraught and pregnant. This situation would surely have overwhelmed a lesser person. That house in Harrell, still standing in 2020 (Page 25), is a small one and could not physically accommodate all the activity thrust upon Ruth. So, Ruth organized an unknown benefactor in Artesian, Arkansas to take in pregnant Mary and care for her and her child. Ruth organized for Dr. J. E. Rhine of Thornton, Arkansas to deliver the child. Today unmarried mothers is a common situation. In those days there was an immense stigma associated with this. Even divorce carried a stigma. Was the Artesian relocation for Mary to relieve her of the humiliation by her classmates, and perhaps relieve Ruth of the humiliation by her peers in Harrell? I don’t think so. I think it was just a byproduct of the situation; that the relocation was dictated by the turmoil in the Johnston household at the time. It was life and death “crunch time” in the Johnston household and Ruth did not have time for social contemplations. Probably Ruth did not have the time or the inclination to convince Mary that this was the best course of action. She probably just informed Mary that this is what we are going to do and it is not open for discussion. If this is the way it was, and this supposition is logical in this circumstance, then it very well could have been a great point of contention and resentment Mary had for Ruth. So Mary went to Artesian, had the child and nursed to the weaning point where the child was sent to Harrell and Big’s care and Mary completed her high school education. Surely Ruth arranged this knowing that in the future Mary would be severely limited without at least a high school education. Ruth continued the management of the Johnston household which entailed the hospice care of CB; going into that room with its fetid, malodorous odor with compassion, skill and determination; the care of two school children; providing food for all of them; and financial control with dwindling resources, no income, no safety net from prior work or the federal government and the country in the midst of The Great Depression with 30% of the work force unemployed. Accomplishing all of this with a bleak future facing her could have been completely overwhelming, but she safely steered her ship of household through this massive storm to calm waters after the death of CB on 22 November 1932. The hell that had dominated the household for several years was passed, but the financial situation remained extremely dire. There was no income and the Great Depression and its effects loomed large. Now Ruth used her imagination and ingenuity. She began serving noon-time meals to the nearby railroad workers for twenty five cents per meal. The former college professor and wife of the town doctor found a way to overcome every obstacle. The next event confronting Ruth was the return to the family of Mary with her Artesian high school diploma, shown in photos on Page 10. It was soon discovered that Mary was once again pregnant. This revelation had to be distressing to say the least for both Mary and Ruth. I think this is where TJ told Mary ‘why can’t you keep your pants on?’ This infuriated Mary and she never forgot it. As stated in this narrative on Page 13, Mary, now an adult, nearly 22 years old and responsible for her own actions, was sent to the Witherington farm where her Artesian schoolmate, Frank Weisinger, was working to inform him that she was pregnant with his child and to see if he would marry her. He did the honorable thing and married her. Frank was a handsome, but simple man. His mind and world revolved around what was needed and what was required in the life of a ‘share cropper,’ which is essentially what he was. He had no vision of further education, of art and culture – only the farmer life that was presented to him. So Mary now the adult, nearly 22 years old, the daughter of a college professor and doctor, was left with the prospects and situation that she had created.

The Johnston household in Harrell continued with little money and scant hope for a better future. Even in very limited circumstances, Ruth never lost her sense of humor. A story she obviously told Vivian and which Vivian told me involved a hefty eater among the lunch time railroad men. Finally Ruth informed the gentleman that she was going to have to increase his meal price to thirty cents. He replied “Oh, Mrs. Johnston, I wish you wouldn’t do that. I have enough trouble now eating twenty five cents worth.” So in 1934 the Johnston household continued with its meager resources supporting Ruth, TJ, Vivian and John. This was the situation for the next four years. Then in the 1938 – 39 time frame Ruth’s brothers came to her rescue. They were prospering in the sawmill business in Hope, Arkansas. They invited the family to move to Hope and offered TJ an important job in the sawmill. The Johnston household world was transformed. The move to Hope, new situation and a change of life. The family income secured and hope for the future. Ruth happily joining her brothers and sisters with bright and unlimited prospects for her children and me. Mary was left with her prospects and situation that she had created.

0 notes

Text

Health Care Needs Its Rosa Parks Moment

BY SHANNON BROWNLEE

On Wednesday, October 25, 2017 I was at the inaugural Society for Participatory Medicine conference. It was a fantastic day and the ending keynote was the superb Shannon Brownlee. It was great to catch up with her and I’m grateful that she agreed to let THCB publish her speech. Settle back with a cup of coffee (or as it’s Thanksgiving, perhaps something stronger), and enjoy–Matthew Holt

George Burns once said, the secret to a good sermon is to have a good beginning and a good ending—and to have the two as close together as possible. I think the same is true of final keynotes after a fantastic conference. So I will do my best to begin and end well, and keep the middle to a minimum.

I have two main goals today. First, I want to praise the work you are doing, and set it into a wider context of the radical transformation of health care that has to happen if we want to achieve a system that is accountable to patients and communities, affordable, effective — and universal: everybody in, nobody out.

My second goal is to recruit you. I’m the co-founder of the Right Care Alliance, which is a grassroots movement of patients, doctors, nurses, community organizers dedicated to bringing about a better health system. We have 11 councils and chapters formed or forming in half a dozen cities. I would like nothing more than at the end of this talk, for every one of you to go to www.rightcarealliance.org and sign up.

But first, I want to tell you a bit about why I’m here and what radicalized me. My father, Mick Brownlee, died three years ago this Thanksgiving, and through his various ailments over the course of the previous 30 years, I’ve seen the best of medicine, and the worst.

My father was a sculptor and a scholar, but he was also a stoic, so when he began suffering debilitating headaches in his early 50s, he ignored them, until my stepmother saw him stagger and fall against a wall in the kitchen, clutching his head. She took him to the local emergency room, at a small community hospital in eastern Oregon. This was the 1970s, and the hospital had just bought a new fangled machine—a CT scanner, which showed a mass just behind his left ear. It would turn out to be a very slow growing cancer, a meningioma, that was successfully removed, thanks to the wonders of CT and brain surgery. What a miracle!

Fast forward 15 years, and Mick was prescribed a statin drug for his slightly elevated cholesterol. One day, he was fine. The next he wasn’t, not because his cholesterol had changed, but the cutoff point for statin recommendations had been lowered. Not long after Mick began taking the statin, he began feeling tired and suffering mild chest pain, which was written of as angina. What we didn’t know at the time was the statin was causing his body to destroy his muscles, a side effect called rhabdomyolysis. Even his doctor didn’t recognize his symptoms, because back then, the drug companies hid how often patients suffered this side effect.

The statin caught up with Mick at an exhibit in Seattle of Chinese bronzes, ancient bells and other sculptures that my father had been studying in art books his whole career. Halfway through the exhibit, he told my brother to take him home; he was too tired to take another step.

Three days later, he was in the hospital on dialysis. The rhabdomyolysis had finally begun to destroy his kidneys. Three weeks later, he was sent home alive with one kidney barely functional. Soon his health would begin to deteriorate at a steady pace.

Fast forward another 15 years, and my father, at 84, was frail, falling down repeatedly, intermittently incontinent, and mildly demented. He had been hospitalized several times over the previous decade for a kidney stone, intractable constipation, dizziness, a small stroke. He was sleeping much of the day and was, as he would tell anybody who would listen, ready to die. He would walk into the ocean, if only he could get to the beach. By then, my stepmother had hidden the gun.

Just before Thanksgiving, Mick was taken by my brother to the local hospital with severe abdominal pain, which turned out to be a volvulus, a twist in the gut that if left untreated can lead to sepsis and a painful death. He was whisked off the hospital in Portland, a two-hour ambulance ride away. Knowing how frail Mick was, and how done he was with being hospitalized much less alive, I told my brother to ask the hospitalist for a palliative care consult. My brother did as instructed. The hospitalist said no, he wasn’t going to call in palliative care, because, and I quote, “We’re not there yet.” In that hospitalist’s mind, palliative care was for those at death’s door, and my father was only in the waiting room. You won’t be surprised to learn that nobody asked Mick what he wanted, or what course of care he preferred.

By the time I could leave work and get a flight from DC to Portland, six days later, my father’s various doctors had managed to give him a pre-op cardiac stress test, and put him on total parenteral nutrition, a sort of food that goes straight into the blood stream. Only then did the gastrointestinal surgeon see him and pronounce him unfit for surgery; Mick was obviously so frail he would likely die on the table or if he survived the surgery, he would spend the rest of his short life in a nursing home.

Finally, we got our palliative care consult, which allowed us to take Mick home, where he was able to die surrounded by his beloved collection of art and his family.

***

I suspect that each of you has experienced some aspect of my tale. We all have stories of being misdiagnosed, ignored, not listened to, and maybe most important of all, not being heard. Of having to fight to get the comfort your child, father, sister needed. We’ve all had to seek out the right care, and be vigilant to avoid the wrong care, too little or too much care. Which probably should not even be called care at all, since if it’s unnecessary, it’s not very caring.

Anatole Broyard, an editor at the New York Times, wrote about the patient’s plight in a brilliant essay he published in August, 1990, 3 months before he died of prostate cancer. He wrote, “To most physicians, my illness is a routine incident in their rounds. For me it’s the crisis of my life. . . I would feel better if I had a doctor who, at least, perceived this incongruity.”Later in the essay he says, “I just wish my doctor would brood on my situation for even five minutes, that he would give me his whole mind just once. I’d like my doctor to scan me, to grope for my spirit as well as my prostate. “

What Broyard so eloquently expressed can be summed up as a crisis of relationship—a fracturing of the therapeutic alliance that we know is essential to offering comfort to patients, but is also part of healing. We all know implicitly, that healing involves far more than the physician’s knowledge and skill. It is more than making a correct diagnosis and delivering the right treatment.

True healing, as journalist David Bornstein writes, “is the process by which a doctor helps a patient accept, recover from, adapt to, or endure a serious illness, and it is full of nuance and mystery. . . I was often moved by how much my father-in-law — an actor who died from a form of leukemia — drew comfort and even inspiration from the relationship he had with his hematologist (who requested a Shakespeare recitation at each visit).”

Or as my colleague Vikas Saini says, hope and healing come from the companionship between doctor and patient in facing an unknown future together. The therapeutic alliance is a two way street, whose destruction also harms those who sit on the other side of the stethoscope — you in the white coats, you have stories, too.

Of being burned out, and chewed up by the system. Nearly half of medical students report feelings of depression, burn out, cynicism. Medical education has been characterized as being akin to living in an abusive and neglectful family. It places unrealistic expectations on students, keeps them sleep-deprived, overstressed, hypercompetitive, and in a state of fear of making mistakes. It sends a message that doubts or grief should be kept to oneself.

Worse yet, young clinicians perceive the gap between what is formally espoused — the proclaimed ethic of medicine’s empathy, compassion and altruism — and what they are actually learning through the “hidden curriculum.” This hidden curriculum is the socialization process that increasingly teaches them detachment rather than connection. The hidden curriculum says money is what matters in the system. The hidden curriculum instructs young clinicians to see patients as “customers,” and to view the doctors with the biggest incomes as the happiest and most admirable. It is even teaching residents to do rounds at the hospital by standing in the hallway looking at their laptops rather than gathering at the patient’s bedside.

What the explicit and hidden curricula are not doing is teaching young nurses and doctors to listen without interrupting much less share decisions. Young clinicians are not even learning the ancient and powerful art of taking a history and physical. The novelist and physician Abraham Verghese is doing a booming business at Stanford medical school running remedial courses for young doctors who are coming to their residencies without those essential skills.

So how can we expect such an education system teach clinicians to “perceive the incongruity” of what it means to be sick versus well? Or to take five minutes to “brood” on their patients’ situation?

It should come as no surprise that five out of six doctors say that medicine is in decline. Close to 60 percent would not recommend it as a career for their children.

And as the work speeds up, and clinicians are treated more like assembly line workers than healing professionals, there is less and less time to grope for the spirit of a patient, to serve as a companion in the face of an uncertain future. There’s no time for such niceties when “productivity” is measured as throughput of patients, and when burnout has reached fever pitch.

What all of this means is the topics of today’s meeting strike at the emotional and spiritual heart of what it means to be a doctor, or nurse, or physicians assistant. This gathering also speaks to the deep need of a patient or family member to be heard, and to be cared for as fellow human being who is suffering.

And what you are all doing today, those of you who have spoken before me or are sitting in the audience, Randi Oster, Geri Baumblatt, Tom Delbanco, Harlan Kumholz, and all of the researchers and physicians and patients who have been laboring in these fields for so many years — every single one of you deserves a medal for making these deep and important issues rise to the surface. For giving a voice to patients — and likewise to the clinicians who care about them as well as for them.

***

And yet . . . here we are today, struggling to make those voices be heard by our colleagues, by our regulators, and our politicians.

Why has it been so hard to get Tom Delbanco’s Open Notes implemented? Why doesn’t every medical and nursing school in the country teach real history taking? How is it that shared decision making has been an idea whose time has been coming—for more than 20 years? Why doesn’t every medical and nursing school in the country teach shared decision-making? Hundreds of studies, thousands of decision aids later, and we know that shared decision-making is a vast improvement over the misinformed consent that so often occurs. Why are these ideas still lurking at the fringes of medicine?

Why do so few hospitals have family advisory councils, and even fewer have councils with real power? Dig even deeper, and we should also be asking why so few communities have any real say in how hospitals allocate resources.

Where I live, in Washington, DC, three hospitals already have a proton beam machine. A fourth is being built. Each one of these machines costs $100 million— and each one is unnecessary. They get built not because they will benefit the DC community, but because they are good for the hospital’s bottom line. And if shared decision-making were actually practiced, and adult patients were actually informed of the fact that there’s no valid evidence to suggest that their cancer will be helped by using this incredibly expensive machine compared with standard therapy, there would be no reason to build another one.

The building of more proton beam machines holds a good part of the answer to why shared decision-making, and family advisory councils, and Open Notes, are not standard practice in every hospital and clinic in the country. And that answer points to the two reasons there are no community advisory councils to prevent every hospital in the country from wasting $100 million on a useless machine.

Those reasons are money and power.

As individual patients, we don’t have much power. It is incredibly hard to advocate for ourselves. Even doctors who become patients find themselves feeling nearly powerless in the face of their fellow white coats.

This idea that the patient/consumer is going to change the system, one transaction at a time, has become part of our national religion of the free market, and the neoliberal catechism we’ve all been absorbing for the last 40 years. That doctrine says that patients can fix the system — if only they would behave the way they do when purchasing other goods. High deductibles will make sick people and their frightened families more “prudent consumers” of health care, and when all those prudent consumers begin to vote with their wallets, the system will be transformed.

Right. How’s that been working out so far?

Here’s an alternative. There’s only so much we can do as individuals, especially when we are sick enough to be under a doctor’s care. Maybe it’s time to think about a different “theory of change.” Maybe it’s time to stop pretending the “market” will fix health care, and start recognizing that we have to pursue a different path. We need collective action.

***

This December, it will have been 62 years since a seamstress named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus. Her refusal and subsequent arrest is just one of many iconic acts of defiance that have come to symbolize the civil rights movement. That movement is ongoing and its business is unfinished, as recent events in Ferguson, Staten Island, and around the country are making clear. But think back to the 1950s and 60s. What an extraordinary distance we’ve come because of collective action by the civil rights movement.

It’s tempting to imagine that all of what has happened since that December day in Montgomery was triggered by a seamstress who was tired and fed up and decided on the spur of the moment to sit in the front of the bus. But that’s not really what happened.

Rosa Parks’ pivotal act of defiance was carefully planned, and it was preceded by years of grassroots organizing that came before. In the first half of the twentieth century, African Americans and their allies mostly fought discrimination through litigation and lobbying, and they set important legal precedents. Yet victories in the courts and legislatures were not enough to change a deeply entrenched culture, and the dream of civil rights only began to make real headway when the activists shifted tactics to real movement building and organizing.

And that organizing began not with a pivotal moment on a bus, but in the black churches. It began when people talked about the lived experience of racism. It was in those churches that people began forming the bonds that made them brave enough to register to vote in the face of police intimidation. Those relationships gave them the courage to face down dogs, and water cannons, and imprisonment for their cause.

It was grassroots organizing that created the bus boycott that followed Rosa Parks’ arrest, and organizing that brought white students from the North to register black voters, and to join marches. It was the endless press releases sent by organizers that made those marchers impossible for the world and the White House and the U.S. Congress to ignore. If the civil rights movement had stayed in the churches and not moved to the next phase, of organizing and mobilizing, just imagine what our world would be like today.

Make no mistake, what we are doing at this meeting serves the same purpose as the years of discussion that happened in the black churches before the movement truly began. But now it is time to consider the next step for our cause, which is real organizing and mobilizing.

Getting shared decision making standard of care, fostering a true therapeutic relationship, giving patients control over their own records and communities control over their hospitals are not technical problems, with technical solutions. They are natural outgrowths from a health care system that has become another business, and a powerful one—one that does not want to change.

In other words, this is a fight about money and power, and in the history of the world, very few people and virtually no institutions have given up either willingly just because it’s the right thing to do. Maybe George Washington really did refuse to become King of America because he believed so fervently in the experiment of democracy. But he is the exception that proves the rule. To change the flow of money and power, we the people must take them.

We need a real movement. A movement that is willing to break glass, step on toes, and picket hospitals to force the deep change that is necessary. Health care needs a Rosa Parks moment.

So here comes my pitch to join the Right Care Alliance. We are just beginning to build our ranks of providers, patients, lawyers and community activists. Our steering committee has started to lay out our strategy for the coming years.

But I have to be honest: We are hardly the only grassroots healthcare movement out there. You can join the National Physicians Alliance, or one of the single payer organizations that exist in every state. It almost doesn’t matter which group you get involved with, because we are eventually going to have to come together to pool our efforts. And our first step will need to involve going into communities and helping Americans understand how bad our health care system really is and what it will take to have a great system. For those of us who are old enough to remember the 60s, you’ll know what I’m talking about when I say we need a strategy for teach ins across the land. Every one of you can be involved in that effort.

Getting to a system that opens the door to patients being active participants can no longer be left to the health care industry, or even to health care professionals. And it cannot be accomplished by patients acting as individual “consumers” in the clinic and hospital. The demand for change must come from the American people, from students, workers, community activists, business leaders, the clergy — and clinicians and patients, all those who are affected by health care’s failure to deliver.

In closing, I want to pay homage to the incredible work that all of you have done. You are testifying to the lived reality of the need for care that makes patients and families true participants. But to achieve our goals, we must take the next step towards activism and organizing.

Shannon Brownlee MSc is Senior Vice President at the Lown Institute and author of the classic Overtreated

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Photo

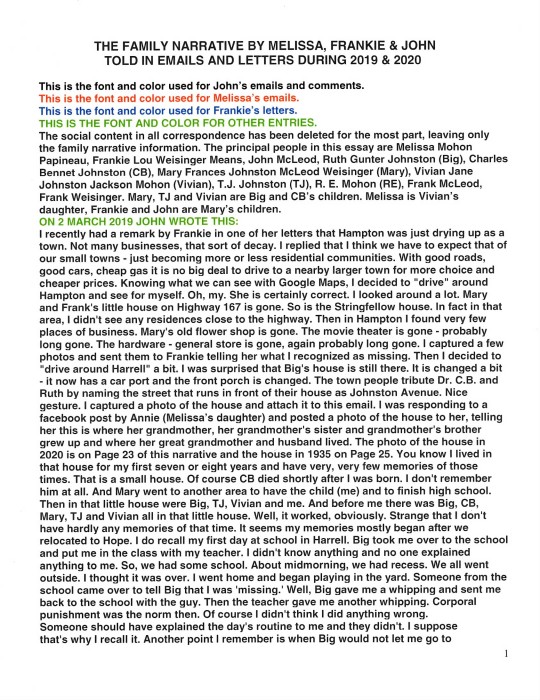

TJ Johnston retired from sawmill work in 1982 at age 65. He was living in the Hope house at 707 East Division Street. He had always done most of the work around the house and very seldom hired outside help. The rain gutters in the house required cleaning. TJ failed to accept that he was now elderly and with less coordination, balance and strength. He undertook this task, one he had always done himself. He fell from the roof, injuring himself and was confined to the hospital. He chose not to go to the care of our family doctor, Dr. Jim McKinsey, in the Branch General Hospital where Vivian was the Chief of Nurses; but went to another hospital instead. Vivian commented that he would not receive optimum care in the facility that he chose. While confined in the hospital he suffered a heart attack and died, ten months after retiring. He had been a smoker for most of his life. While the fall did result in severe injury, surely it was demon tobacco that took his life.

Vivian was the Chief of Nurses at Branch General Hospital. In addition to her administration tasks, she also worked in the cancer ward of the hospital. She developed a chronic cough. Dr. McKinsey, who she worked with there, kept urging her to check out the cough. Finally she made a chest X-ray. She told me “when I saw those X-rays I knew I was looking at my death warrant.” She had lung cancer. She had been a smoker most of her life and was a smoker then. She had surgery but all the cancer could not be removed. She was given six months to a year to live. In about a year the cancer returned. It was demon tobacco taking another life.

I, John McLeod, also smoked as a youngster as most people did in those days. I smoked for about ten years and finally became disgusted with the filthy habit. This was before we knew that tobacco could and most likely would kill you if you used it. Ridding myself of the demon tobacco was the most difficult thing I did in my life. I attribute a heart attack I suffered in 1999 to the demon tobacco. Today I continue life with high risk from cardio vascular disease. I wrote a blog about the demon tobacco. Create a hyperlink on your computer with the following address, click on it, and you can read the blog. If you are reading this on a computer connected to the Internet, that is a hyperlink. Just click on it. https://JohnArk.Tumblr.com/tagged/tobacco

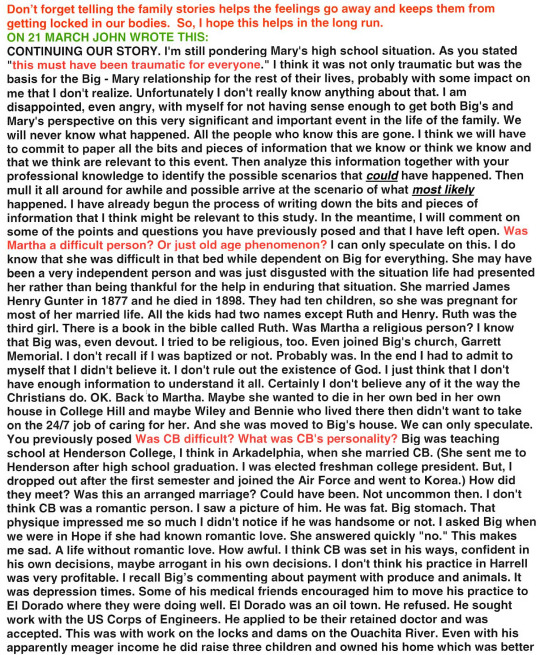

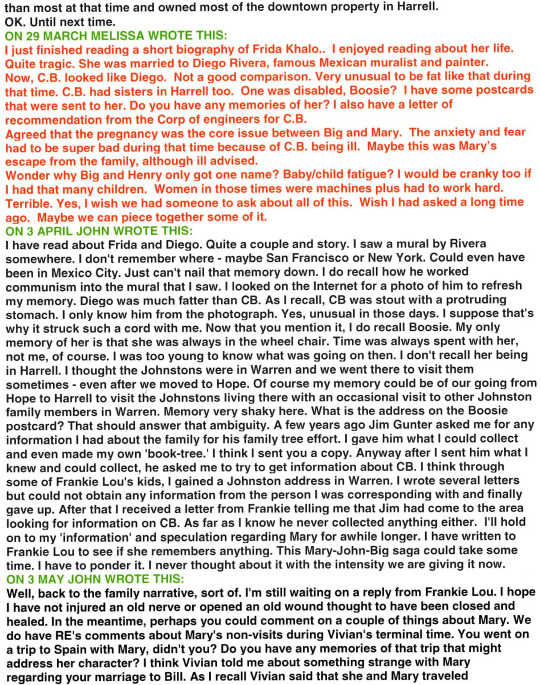

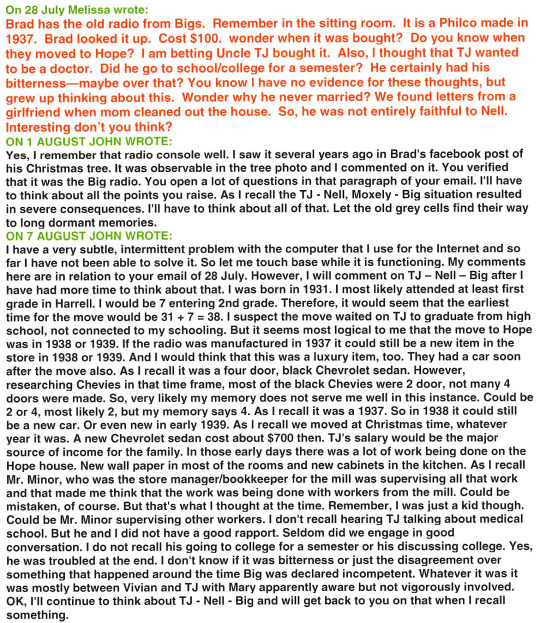

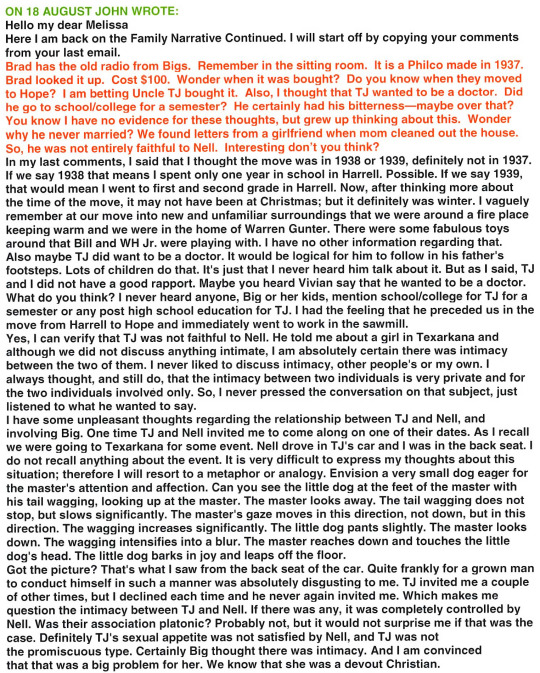

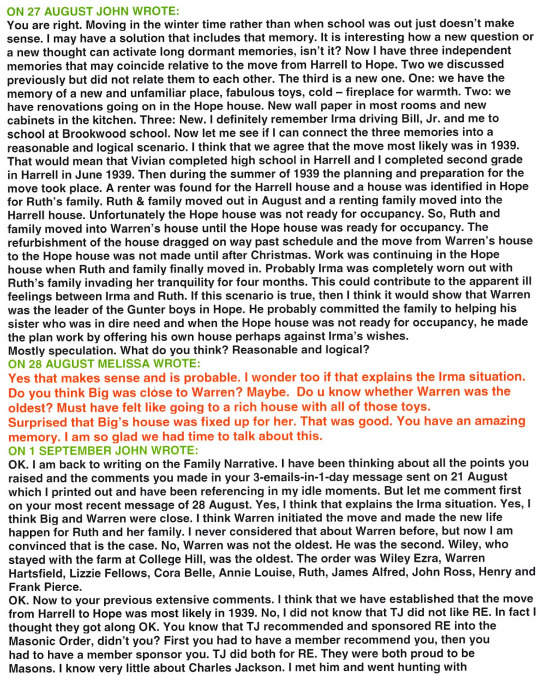

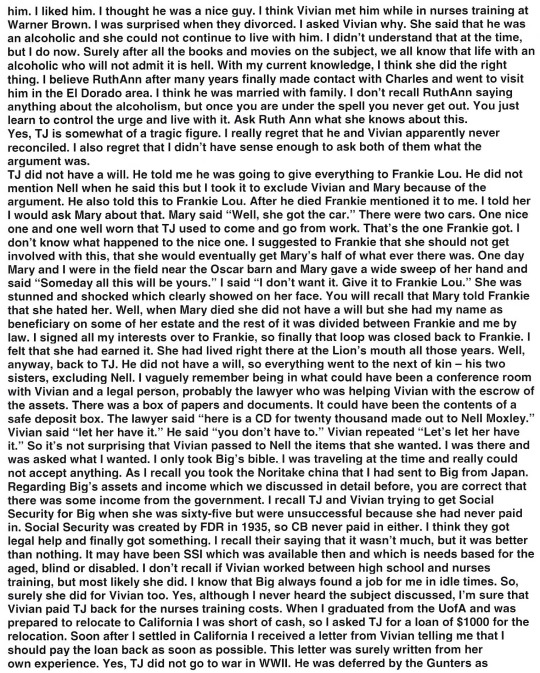

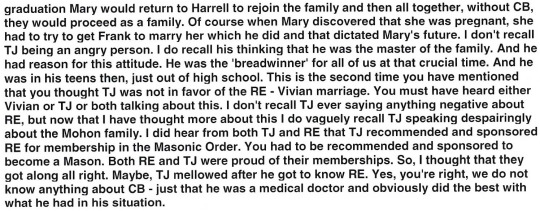

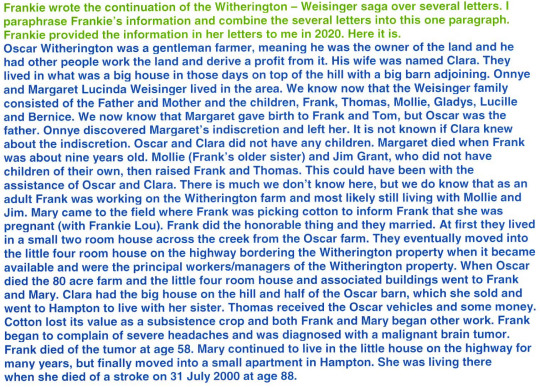

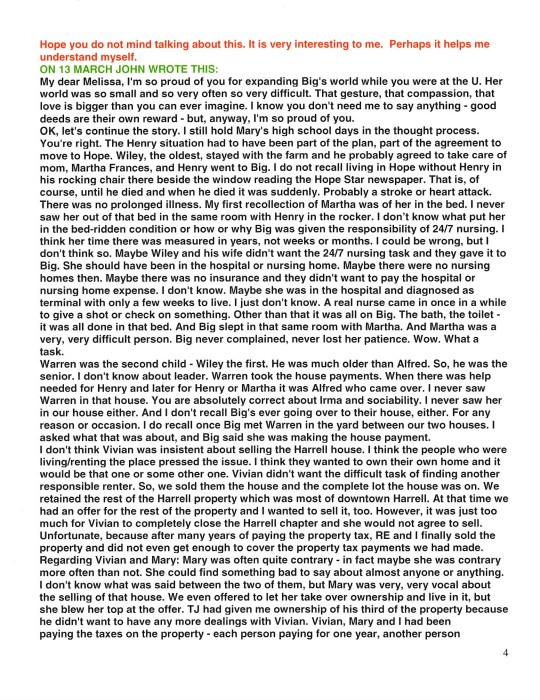

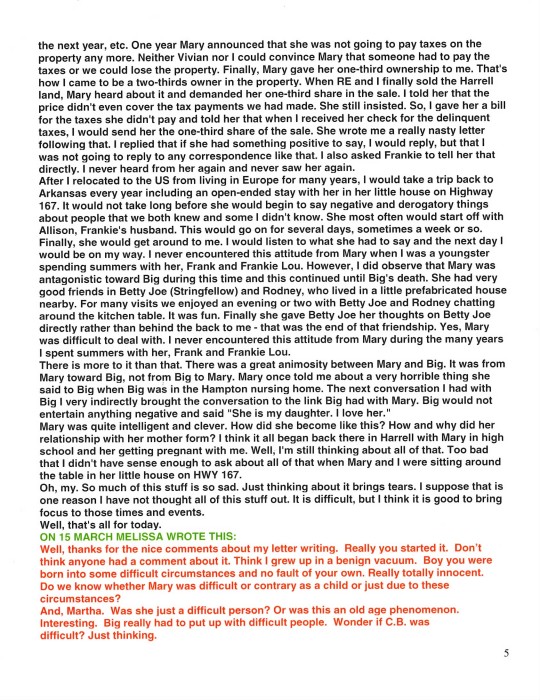

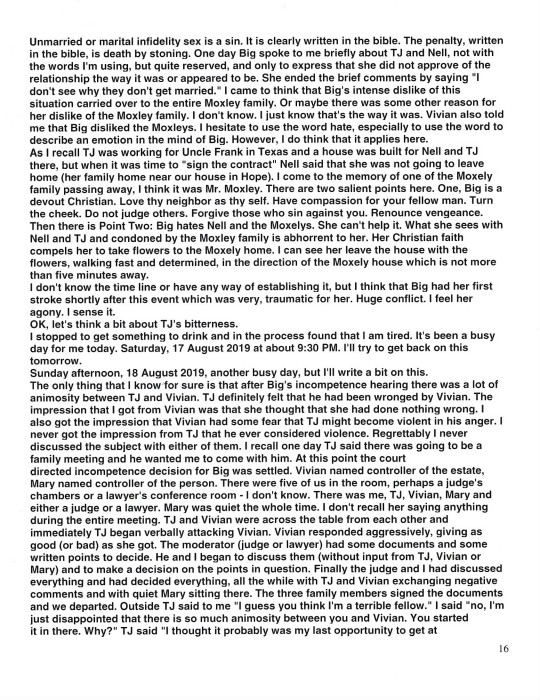

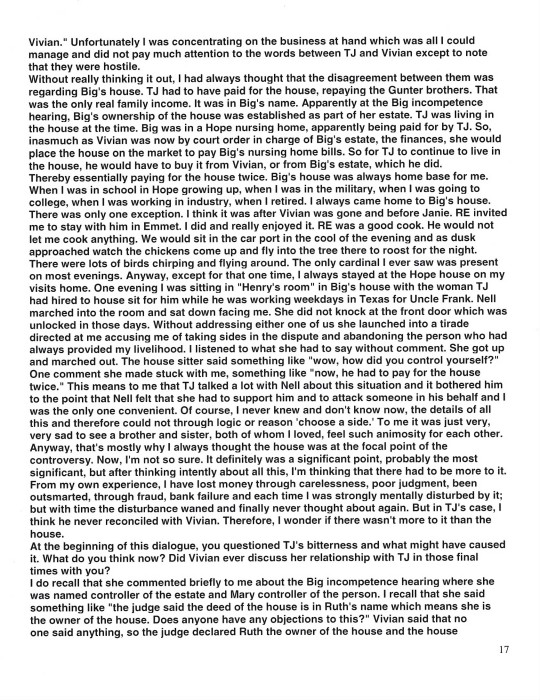

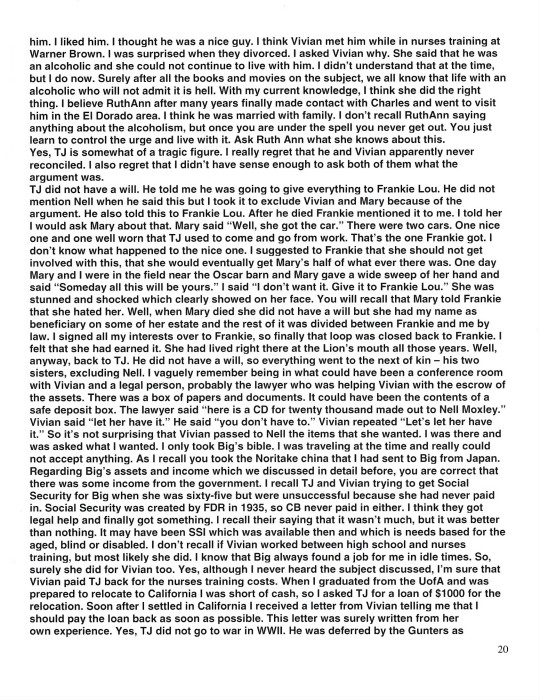

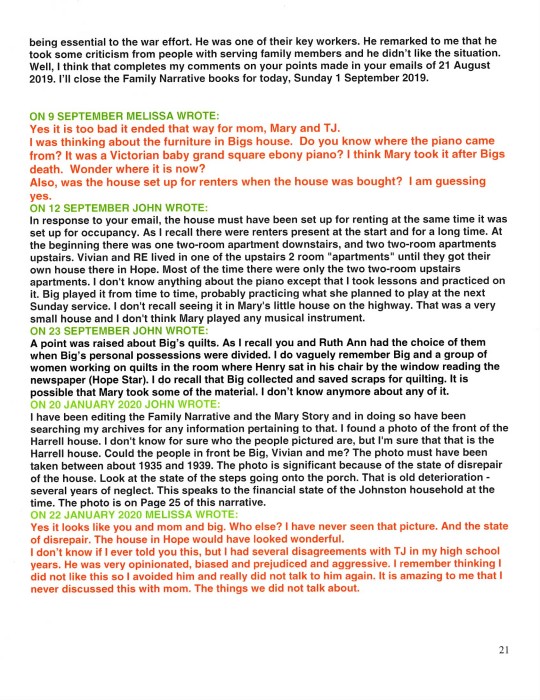

MELISSA’S FAMILY IN 2018

From the left: Bradley Mohon Papineau, Mateus Lima, Melissa Mohon Papineau, Anne Papineau Nelson, Mikael Nelson, William Edward Papineau.

In this narrative we have briefly stated that Big cared for her dying husband in difficult circumstance in Harrell in the early 1930s and later cared for her dying mother in her home in Hope. The comments about Big’s caring for her mother, Martha Frances, are on Pages 4 and 6 of this narrative. I observed this and was amazed at Big’s skill, patience, compassion and strength both physically and mentally in dealing with what I observed as a very difficult person and difficult situation. I was just a kid at the time, but I was mature enough to recognize an extraordinary life and death event unfolding in that room and appreciate what I was seeing. But even more extraordinary and astounding as well is how deplorable conditions, devastating events, surprising and disappointing betrayals around the final two years of the life of her husband, Dr. Charles Bennett Johnston (CB), were met with such extraordinary determination, loyalty, skill, organization, perseverance, compassion, dedication, endurance, improvisation, stamina, grit, moxie – need I go on? This was indeed an extraordinary situation confronted and overcome by a more than equally extraordinary person. I want to add to what has been said about this in this narrative on Pages 2, 21, 22 and 23.

Let me start by trying to establish the situation in the Johnston household in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Vivian told me that Charles B. Johnston died of Parkinson’s disease. This disease is a progressive, untreatable, incurable nervous system disorder manifested with movement disorders, autonomic dysfunction, neuropsychiatric problems among others. The end stage of Parkinson’s is an extremely distressing situation. Today hospice takes over at that point. Family cannot provide or endure care at that point. CB probably suffered with incontinence, insomnia, dementia, hallucinations, severe posture issues with back, neck, hips and was surely bedridden. Just think of a bedridden heavy man, drooling, urinating uncontrollably, with induced diarrhea to relieve constipation, depressed, and demented. It would have been impossible for Ruth to have cared for CB alone. However inexpensive, inexperienced assistance could have been available from the black community. Surely Ruth would have expected assistance from her children – Vivian 9 or 10, TJ 13 or 14 and Mary 16 or 17. The situation in CB’s room must have been hell. And probably smelled that way, too. Hell at that point and the future very bleak. The country was in the midst of the depression with 30% of the work force unemployed. Is this the reason that Mary dropped out of school, abandoned her family and ran away with Frank McLeod? What about family loyalty, personal responsibility, conscience? What did Ruth think when her oldest daughter abandoned her in the time of most need? Yes, abandoned. Fled. That’s the way it looks to me. Yes, living with Frank would have been “wonderful” compared to the hell that existed in the Johnston household. Had she stayed with Frank, as it turned out, it would have been a blessing for Ruth. But rather than escape from it, Mary returned just in time to add to that hell and responsibility for Ruth. I was born on 21 September 1931. CB was in the last, tortured year of his life. He died on 22 November 1932. So, in summary, the situation for Ruth at the return of pregnant Mary was: caring for CB in the direst and most demanding period of his declining health, supervising untrained CB care givers, caring for two high school children, managing a household, managing the family finances, and now Ruth has to organize the care of Mary and the child and deal with Frank McLeod. Probably Mary demanded that Ruth force Frank to marry her. The fact that Frank sent her home probably meant that he would not easily agree to this. Hiring an attorney and settling the situation through the courts if required was most likely out of the question because of finances, time element, physical location and life and death responsibilities. Probably in the interests of a quick settlement of the issue, Ruth and Frank agreed upon marriage, separation, no contact, no responsibility. And Frank went happily on his way, leaving Mary angry, distraught and pregnant. This situation would surely have overwhelmed a lesser person. That house in Harrell, still standing in 2020 (Page 23), is a small one and could not physically accommodate all the activity thrust upon Ruth. So, Ruth organized an unknown benefactor in Artesian, Arkansas to take in pregnant Mary and care for her and her child. Ruth organized for Dr. J. E. Rhine of Thornton, Arkansas to deliver the child. Today unmarried mothers is a common situation. In those days there was an immense stigma associated with this. Even divorce carried a stigma. Was the Artesian relocation for Mary to relieve her of the humiliation by her classmates, and perhaps relieve Ruth of the humiliation by her peers in Harrell? I don’t think so. I think it was just a byproduct of the situation; that the relocation was dictated by the turmoil in the Johnston household at the time. It was life and death “crunch time” in the Johnston household and Ruth did not have time for social contemplations. Probably Ruth did not have the time or the inclination to convince Mary that this was the best course of action. She probably just informed Mary that this is what we are going to do and it is not open for discussion. If this is the way it was, and this supposition is logical in this circumstance, then it very well could have been a great point of contention and resentment Mary had for Ruth. So Mary went to Artesian, had the child and nursed to the weaning point where the child was sent to Harrell and Big’s care and Mary completed her high school education. Surely Ruth arranged this knowing that in the future Mary would be severely limited without at least a high school education. Ruth continued the management of the Johnston household which entailed the hospice care of CB; going into that room with its fetid, malodorous odor with compassion, skill and determination; the care of two school children; providing food for all of them; and financial control with dwindling resources, no income, no safety net from prior work or the federal government and the country in the midst of The Great Depression with 30% of the work force unemployed. Accomplishing all of this with a bleak future facing her could have been completely overwhelming, but she safely steered her ship of household through this massive storm to calm waters after the death of CB on 22 November 1932. The hell that had dominated the household for several years was passed, but the financial situation remained extremely dire. There was no income and the Great Depression and its effects loomed large. Now Ruth used her imagination and ingenuity. She began serving noon-time meals to the nearby railroad workers for twenty five cents per meal. The former college professor and wife of the town doctor found a way to overcome every obstacle. The next event confronting Ruth was the return to the family of Mary with her Artesian high school diploma, shown in photos on Page 10. It was soon discovered that Mary was once again pregnant. This revelation had to be distressing to say the least for both Mary and Ruth. I think this is where TJ told Mary ‘why can’t you keep your pants on?’ This infuriated Mary and she never forgot it. As stated in this narrative on Page 13, Mary, now an adult, nearly 22 years old and responsible for her own actions, was sent to the Witherington farm where her Artesian schoolmate, Frank Weisinger, was working to inform him that she was pregnant with his child and to see if he would marry her. He did the honorable thing and married her. Frank was a handsome, but simple man. His mind and world revolved around what was needed and what was required in the life of a ‘share cropper,’ which is essentially what he was. He had no vision of further education, of art and culture – only the farmer life that was presented to him. So Mary now the adult, nearly 22 years old, the daughter of a college professor and doctor, was left with the prospects and situation that she had created.

The Johnston household in Harrell continued with little money and scant hope for a better future. Even in very limited circumstances, Ruth never lost her sense of humor. A story she obviously told Vivian and which Vivian told me involved a hefty eater among the lunch time railroad men. Finally Ruth informed the gentleman that she was going to have to increase his meal price to thirty cents. He replied “Oh, Mrs. Johnston, I wish you wouldn’t do that. I have enough trouble now eating twenty five cents worth.” So in 1934 the Johnston household continued with its meager resources supporting Ruth, TJ, Vivian and John. This was the situation for the next four years. Then in the 1938 – 39 time frame Ruth’s brothers came to her rescue. They were prospering in the sawmill business in Hope, Arkansas. They invited the family to move to Hope and offered TJ an important job in the sawmill. The Johnston household world was transformed. The move to Hope, new situation and a change of life. The family income secured and hope for the future. Ruth happily joining her brothers and sisters with bright and unlimited prospects for her children and me. Mary was left with her prospects and situation that she had created.

0 notes