#actually the moral of the story is how averse i am to asking harmless questions. you could get me to walk into

Text

apropos of nothing, but i suddenly remembered this baffling encounter i had with acupuncture back when i was in college. my mom got acupuncture and it helped her quit smoking (which, yay! whatever works, works!) and then she made me go to try to see if it'd cure a neurological condition i have (which uh, im neither here nor there over alternative medicine and whatnot but in her defense, i had had countless inconclusive diagnostic tests abt this condition so she was very much grasping at straws here for anything that would help me) and since im a good boy who follows what his mother says, i said "okay" and it was a pretty alright experience. i was and am currently still not very squeamish with needles so it didnt bother me very much. if anything, i just took the weekly acupuncture sessions as an hour to nap (with needles in me). but then one day, one of the needles (that went into my abdomen) had a....thingy at the end of it. it looked like a large-ish cork thingy balancing atop of the needle. and i was like "huh, what is that?" but i didnt say it out loud because of my debilitating anxiety and worry and i didnt wanna come off as the weird guy who asks too many questions at the acupuncturist. so i didnt ask. and the acupuncture guy thusly did not explain.

then he set the thingy on fire. and then he left the room.

i dont know about you, but in general i was taught that fires should not be left unattended. that goes for normal fires, but this was a fire lit perilously at the end of a needle sticking out of my abdomen. i guess i was the person attending to the fire, but like, i couldnt move. because of needles in me. it was a harrowing hour. i could not nap. there was an on fire thingy connected to my body. i spent a whole hour laying down alone with my thoughts and also with a small on fire thingy as company.

theres no moral to this story, it's just one of those things that made me go "hey what was that all about" but i never asked because i dont wanna be the weird guy whos not cool with fire needles

#actually the moral of the story is how averse i am to asking harmless questions. you could get me to walk into#speeding traffic with no questions asked if you said it to me sternly enough like yessir got it completely understand here i go#dootdootdoot#needles cw

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

//s:sok rant incoming

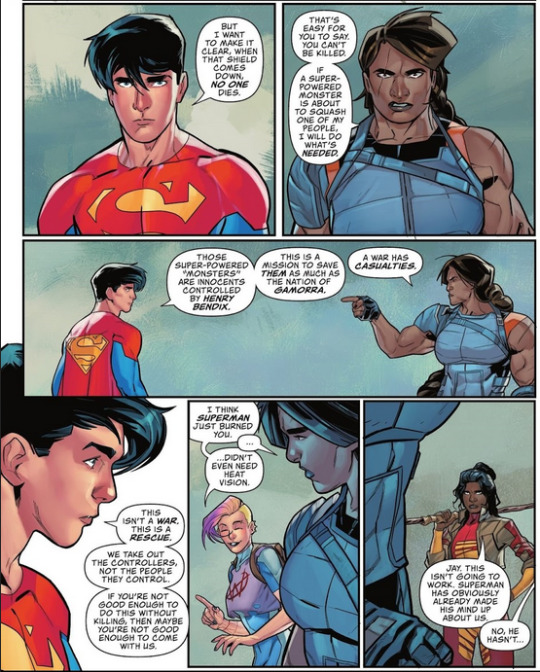

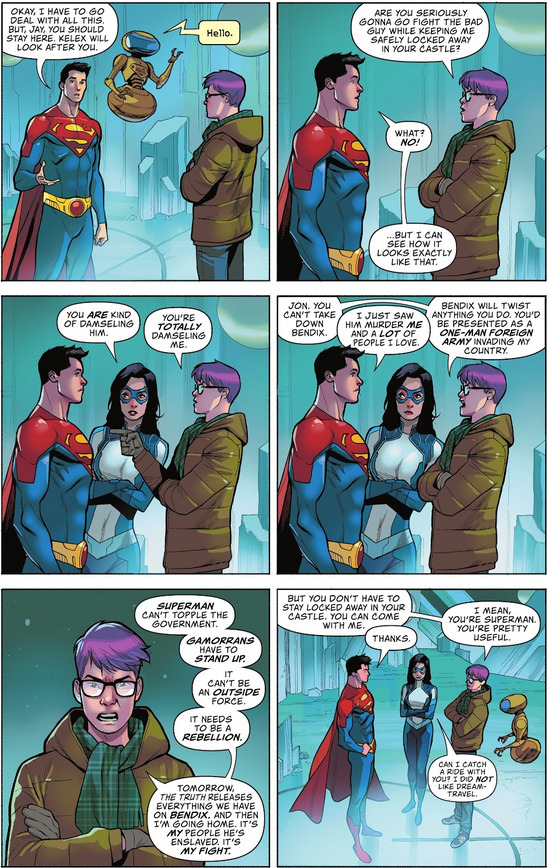

i keep seesawing wildly between "s:sok is fine, it's just slow-paced" and "s:sok has a three-book arc spread out across over ten issues but doesn't have enough conflict for even two." some of this stuff is good. the truth, at least on paper, is kind of interesting, and it has potential to ask questions about the state of the news and ethics in reporting. jay is potentially an interesting character. now that bendis has ruined everything, it's a good idea to do with that what you can by picking up jon where bendis left him. and while tom taylor writes for panels to be taken out of context on social media so people can share it for how wholesome it is, it still gets me sometimes! i am not immune to damian calling himself jon's best friend and them hugging! i am not immune to gail's cubs! but at least part of the reason s:sok-- and nightwing, too, to be honest-- feels so unrushed and amorphous is that tom taylor is averse to letting there be any kind of interpersonal conflict between any of his characters. every time there seems to be a hint of disagreement it's smoothed over within one issue, max.

(Maybe Osista will actually kill someone next issue! Maybe there'll be conflict! But probably not.)

(Oh thank god the revolutionaries are completely harmless and batman was unquestionably wrong. that might have been a tangled situation! but we know batman is wrong because jon thinks he is, dick thinks he is, and pa kent took batman aside to explain to him that he doesn't need to worry about it. (also was he expecting jay to say yes if he was?))

i'm still hoping jay's gonna turn out to be some kind of villain because that'd be interesting. you can still write interesting romance dynamics between characters that are aligned-- jon's parents are a readily available example-- but they still need to actually have some kind of dynamic and that usually stems from some kind of conflict, even if it's just in their personalities. jay and jon are too similar. their conflicts are things like "you're not leaving me here while you go fight the bad guy", and that's laid to rest within six panels. less than that, even. whenever they have differing opinions and approaches it doesn't last; one of them falls into line with the other.

(i didn't have this panel open when i was writing this. i forgot jay literally called bendix "the bad guy."

isn't jon's whole thing supposed to be that he's hung up on being able to save everyone, and because jay can go intangible he doesn't have to worry about him? with that you could go two ways: either he trusts jay to look after himself, and in doing so jay gets hurt or something else like that and jon experiences remorse, or you can persist in having him worry about jay and in doing so stifle his agency and be confronted about it. neither of these work when they're constrained to a half-joking six-panel conversation. because jay is fine. his mum's evil now but he's fine.)

and it's an issue that pervades the entire cast. batman, whose super power is paranoia, is suspicious for an issue and then he backs off because he was told to chill. lois, damian, dreamer, and the revolutionaries all talk the same and have the same or similar goals that go beyond just shared interests. no one feels distinct. they feel like props to the generic superhero story that's being spun, where you're either with jon or you're against him, and there's no room for anything in between. because that might spark conflict that isn't as easily solved as fighting evil mcEvil bendix, monolith of evil, without any moral nuance at all nor interest because he's a generic white guy in a suit. but it's gonna take months to fight evil mcEvil because it's just not that urgent.

and look, maybe it is silly to want or expect more than that. it's a superhero story. it's about a guy who's half alien and can fly. all he really needs to do is beat up the bad guy. but it feels inept within the genre. golden and silver age comics may have had a similar conflict, but they wouldn't have been dragged out over 14+ issues, and they'd be a tighter and more interesting story for it. and comics can be good in terms of complexity! you don't need to be alan moore to write something a bit more complex than a superhero beating up a bad guy because he's bad and the superhero is right. but i guess screencapped panels posted to social media don't translate so easily if you need context to understand them. so you keep it simple.

#DC#EWMWMBWE#all panels are taken from superman son of kal-el etc#and if the final issue of this arc in however many months proves jay to be a villain and batman was right and the truth is corrupt etc#it'd be more interesting. but the 15+ issues leading up to it still would have been slow-paced and without conflict#and what GETS ME is that in the first issue it promises so much more than what's happening

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Problem With Tech

Disclaimer: The opinions reflected in this essay are my own and do not represent LinkedIn, Inc. For any questions regarding LinkedIn, please direct inquiries to [email protected].

(don't wanna be sued or fired, so...)

Juicero is the hot new joke right now. A startup offering a $400 juicer (or juice bag squeezer, I suppose) that has an internet connection and QR scanner to keep you from drinking anything that's spoiled or recalled, with the distinct side effect of being legally unable to obtain your juice if the scanner breaks, your internet or Juicero's server goes down, someone hacks the juicer, etc etc. When a company has to issue a statement asking people to not manually squeeze their product despite it being both easy and the purpose of the product, something has gone horribly awry.

And we laugh and we mock, but underneath it all I feel that this is an issue that's perfectly representative of some of THE crucial issues in West Coast Tech right now (I would say Silicon Valley, but Seattle and Los Angeles companies are equally guilty). Some of you must be wondering how this could have possibly gotten through four rounds of investing, extensive design and user testing, and release before these issues came up.

It's not that they didn't know. It's that they didn't care.

There's a lot of factors that led us to this point, but I'm going to narrow it down to what I think are the four biggest: An idolization of "intelligence" as a supreme moral good, a conflation of success with intelligence, a lack of personal responsibility for consequence, and a widespread sense of complacency.

To start off: I am a software developer working for LinkedIn, and I currently live with three other software developers: two of them work for Google, one works for Facebook. Our broader local social circle consists almost exclusively of developers, mostly Google but also Uber, Infer, Palantir, and the like. And while I can't claim this is a universal attitude amongst tech, at least amongst this group, everything is an optimization problem. Playing board games, especially euro games, is an excruciating process where they can take upwards of twenty minutes to take a single turn, taking the time to analyze decision trees and modeling other players strategies and decisions. But they also seem to be completely ignorant of board games as a social function. My roommate who optimizes most is, as a direct result, very good at board games. But when players act against him to prevent him from winning because he always wins if we don't stage intervention, he protests. When someone makes a move he's deemed suboptimal, and it ends up being a benefit to them over what he thought was optimal because he didn’t anticipate it, he still couches it in language of "the wrong choice" or "what they should have done".

Because this group values optimization, efficiency, and intellect above all else. Obviously, this has a lot of issues, as "intelligence" as a quality has a long and storied history of being used to denigrate others and justify oppression, despite it being, just as anything is, a collection of unrelated skills that people can have varying amounts of practice at, and in practice far less important than dedication and willingness to practice and learn. Intelligence, as the public regards it, seems to mean "skill at mathematics, logic, memory, and reading comprehension, as well as rate of skill acquisition in these areas". But when you treat it as a general marker of value, we start getting problems.

This ties into the next point: Tech regards success as a marker of intellect, and therefore a moral good. When Elon Musk joined Trump's advisory board, there were arguments about whether or not it was good or bad, if it was lending legitimacy to Trump and cozying up versus an attempt at harm minimization. Regardless, people protested and boycotted, and I saw a former classmate respond that we "mustn't shame the smartest people in the country". And that really stuck with me. Putting aside the Tesla, which is admittedly a massive advancement towards renewable energy vehicles, and the advisory board debate, Musk has made some intensely strange causes as his goals, such as brain uploading and other transhumanist causes, which some might argue shows a disregard for accessibility or practicality, while simultaneously disincentivizing those who work in the Tesla manufacturing plants from unionizing by attempting to placate them with frozen yogurt. He also claimed that the unions were an unjust tyrant over a powerless oppressed company by likening it to the tale of David and Goliath. Panem et circenses, indeed.

In short, there is much about Musk to criticize. To claim he should receive immunity from this criticism by virtue of intellect is concerning to say the least, but it's an idea that's present in the tech community at large, from the rationalists at LessWrong.org to the Effective Altruism movement, and on down to the people who, in complete seriousness, advocate for Silicon Valley to lead the world, with Elon Musk as CEO of the United States. The form differs, but the underlying idea remains the same: the best thing one can be is smart, and since we are successful, we are the smartest and therefore the best.

However, despite feeling responsible enough for the well-being of the world to oh-so-magnanimously offer to take the reins and save the common masses from themselves, tech has a consistent problem with personal accountability. Facebook was, and remains, a prime means of spreading misinformation. But it took massive outcry for them to cop to their complicity in this matter or to take action. And this manifests in so, so many ways. One of my roommates refuses to act as though the rising costs of living in the Bay Area are detrimental, claiming that the influx of tech into SF is harmless because "cities are made to house people" and "tech has buses to get employees to work, so that lower income workers are driven further away from work isn't a problem" (ignoring the historical and cultural issues at play in gentrification, a rising sense of entitlement, and the fact that most tech companies only offer such luxurious benefits to their salaried and full time employees, not the contractors or part time workers, a.k.a. the workers who make the least, have the most trouble securing consistent transportation to work, and are most necessary to the upkeep of the offices and the benefits they provide while receiving the least respect and compensation. But hey, at least the buses have WiFi so you can work while you commute!)

And that's not the worst example. An acquaintance, who has thankfully moved very, very far away, once attended our weekly board game nights. He was a software engineer for Facebook. For those unaware, ad revenue is the prime, and essentially only, stream of revenue for Facebook. As part of compensation, workers receive ad credits, to be used for ads on Facebook. And this acquaintance once had an idea. He convinced his fellows to pool their credits together, and with it, he purchased an advertisement with the following stipulation: This ad would be served to all women in the Bay Area within the age range of roughly 23-30 or so. The content of the ad was simply his picture and the phrase "Date <acquaintance's name>" (at least, as he related it to me. I thankfully never witnessed the ad directly).

Now, given the fact that tech is incredibly male dominated and hostile to women, one would think this ad is at best tone-deaf and at worst horrifying. And yet, he related this to me in candor, treating this all as a joke that had gone awry. When I raised the possibility that this was literally harassment, regardless of any potential joking intent, I was met with blank stares and an insistence that it was hilarious and not serious (of which I remain unconvinced). Granted, one of the women targeted by the ad was his ex-girlfriend, who lodged a complaint, and the acquaintance was subsequently fired for his conduct after a massive scandal about the potential issues regarding the invasiveness of targeted advertising and how it contributes to a culture of exclusion.

Just kidding! There was a single local story about it where he was kept anonymous and he got a slap on the wrist and a book deal about his experiences dating in Silicon Valley as a software engineer. The book can be purchased on Amazon and while I haven't read it, nothing about the title, description, or author bio implies to me that he is even remotely repentant, beyond a vague sense that his missteps are due to being *socially awkward, but in an endearing way* as opposed to, you know, actively curating and supporting a toxic environment for women.

And it might seem as though these examples are simply bad eggs, but they really aren't. They're just symptoms of an industry that looks at a lack of diversity and, rather than seriously examine why women don't stay in industry and how the culture they so take pride in is complicit, decide that obviously it's just that being programmers didn't occur to women, so we've just got to make programming seem fun and feminine, right? Just lean in, women! Just grit your teeth, prepare yourself for an unending nightmare of disrespect and abuse, and lean in! And that's not even remotely approaching the severe underrepresentation of black and Latinx people in tech.

But I digress.

Where does this aversion to responsibility come from? There are so many possibilities. But the one most unique to West Coast Tech is the corporate culture, or perhaps, the lack thereof. It's a land of man-buns, flip flops, and company t-shirts. My roommate owns a combination bottle opener and USB drive, proudly emblazoned with Facebook’s logo. The brogrammer is alive and thriving. And to be completely fair, this culture is actually something I quite like about working in tech (The casual part, not the acting like a college freshman part). That I may be frank in my discussions with my co-workers, swear profusely and use emojis in email, and casually discuss my mental health with the man three steps above me in the corporate hierarchy (and two below the top) is quite refreshing. But it has drawbacks.

I attended a college that required a minor in the humanities, and had as its mission statement to educate people in STEM who would understand the impact of their work on society. But so many people just viewed those requirements as an obstacle, or just took economics and got the takeaway of how to best impact markets. And most colleges don't even pay lip service to such a goal. So I worry that "casual" is code for "unwilling to examine potential harm caused by one's actions". That the culture is why harassment can be seen as "just a joke". Why anyone who feels unwelcome is just "too uptight". Why people can be reasonably othered and rejected in interviews because of "a lack of culture fit". And without a willingness to accept responsibility for the consequences of actions, nothing will change.

This ties into the final point: the complacency. Everyone in tech wants to be seen as changing the world. But I'm also privy to the conversations we have in private, and you know what we care about more? Compensation. Its pretty rare that someone I know will come home from work and express that hey, their company is working on something that will legitimately help so many people. More often, we have discussions about who has the better offices, or the best snacks, or the best free meals. I like to think I'm a kind person, but is that really true? I may profess to be aware, but I still own no fewer than ten garments with LinkedIn's logo on them. I still take full benefit of all of the compensation, including free breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and great insurance, and a free gym. I still just used my ludicrous paycheck to purchase a condo instead of anything magnanimous or truly worthwhile. And my fellows are much the same.

The irony that I wrote this entire essay, on company time, on a company device, because today is the Friday per month we get to devote to professional development and is discounted in work estimates because we are expected to do something other than our normal duties (read: not come to work) is not lost on me.

I touched earlier on the Effective Altruism movement, which is comprised primarily of tech and tech-adjacent workers. I remain somewhat critical of the movement, for a number of reasons. Firstly, there is a focus on its own impact while simultaneously continuing the trend of disavowing consequences. One of the most notorious discussions in Effective Altruist groups is the avoidance of a theoretical AI that could eliminate humanity. This conversation seems to be staying in the wheelhouse of safety of testing of AIs that don’t seem to be anywhere close to a reality, rather than more concrete examples of how tech reinforces power imbalances, like, say, advertising algorithms that reinforce racist stereotypes. The second criticism I have is that for many of the metrics used by EA to measure the effectiveness of charities are purely monetary: how much of what goes in goes back out. This ignores other factors, such as raising awareness, operational costs at various sizes and scales, and a question of how directly does money even translate into benefit? The good done per dollar is not considered, merely dollar preservation from donor to donee. Furthermore, that the natural extension of Effective Altruism is that, in order to be a good person, the best thing one can do is obtain a high paying job (such as one in tech) and donate money, rather than donate time by volunteering, strikes me as convenient justification rather than honest analysis.

This excellent article (which by and large inspired this one) touches on many of these issues, but I would like to highlight one statement in particular: “Solving these problems is hard, and made harder by the fact that the real fixes for longevity don’t have the glamour of digitally enabled immortality.” As Emily Dreyfuss points out, Silicon Valley has very little interest in actually bringing about progress. Silicon Valley is trying to sell you on the idea of progress. They want to peddle you a “The Jetsons”-style future, but instead of the post-scarcity society that has mastered space travel, they want you to buy Rosie the Robot Maid. Helpful? Sure. Revolutionary? Hardly.

It's perhaps unrealistic to expect tech to actually do the hard, thankless work to improve the world, but it's certainly not unfair to expect them to at least be honest. LinkedIn is more benign than most tech companies: it is, for all intents and purposes, a resume book masquerading as a social network. The adage goes that "if you're not the customer, you're the product" and that rings true in tech. In exchange for use of the site, people surrender their information to the company to be sold as potential customers to advertisers. At least with LinkedIn, that's the expectation and goal. People give LinkedIn their resume and employment information and LinkedIn, in turn, lets recruiters look for leads. But the users more or less expect and want this, because they joined for the express purpose of finding job opportunities. But that this is benign doesn't mean it is revolutionary or radical. It remains only useful to white collar employees. Blue collar workers have no use for LinkedIn, and we can hardly claim to be changing the world of employment when the people who need us most can't benefit from the services we offer.

Could I go and find a company that does nobler work, or enter academia to advance at least the collective knowledge of humanity in some way? Sure. Will I? No. I am selfish, and don't want to give up my cushy job, and cushy benefits. And I'm not the only one.

The most interesting thing to me about the Juicero debacle is how with even the slightest forethought, they could have actually done something impressive. Consider the As-Sold-On-TV devices you see sold: I mean, who really needs a one-handed spaghetti twirler, right? Well, people with motor control issues or disabilities, is who. People who struggle with tasks most consider trivial. But people don't care about that, they care about what can be marketed, so we instead act as though the world is simply excessively clumsy and hope that someone who really needs that extra help sees it.

So, consider the Juicero bag. Reporters have noted, laughingly, jokingly, that the bag is exceedingly easy to squeeze and thus remove juice from. It's so simple, it requires hardly any effort! Someone went through the process of designing a bag, meant to be able to dispense its contents far more easily than other bags, as well as a device to automate the squeezing. Now I don't have motor control issues or disabilities, but I'm willing to bet: someone who does? Or who can't easily get, say, orange juice cartons from the fridge, open the top, lift the heavy, irregular object at just such an angle in just such a location for just such a time, all to get themselves a cup of juice? Yeah, I bet someone, somewhere, saw this and thought, finally, I can actually get myself milk without needing help or preparation.

And Juicero made this device, slapped an internet connection, QR Codes and a $400 price tag onto it, and marketed it as being the future of juice, vulnerabilities and use cases be damned. And I want to scream.

Because in the end, they cared more about being successful than being helpful.

Unfortunately, identifying the issues is one problem, addressing them is another. I'm not sure how to even begin tackling these. But we have to. People in tech, myself included, need to take responsibility for our culture and creations. We have a moral duty to do better. To be better. The internet is, at its core, a wonderful tool for accessibility of information. But like all tools, it can and is misused, and we're the ones who let it happen. We need to fix this.

6 notes

·

View notes