#alexander wardlaw

Text

It’s missing Rhinos hours :’))

Credits: x

#my faves <3#andrew masters#david james jeremy#joakim erdugan#matthew wrankmore#tom cross#callum wardlaw#hayden sayers#alexander wardlaw#jason polglase#heheh that’s a lot of dudes#central coast rhinos#aihl

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just Liverpool players being dorks

omg..she cute 😍

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

3rd February 1414 – University Privileges Arrive in St Andrews

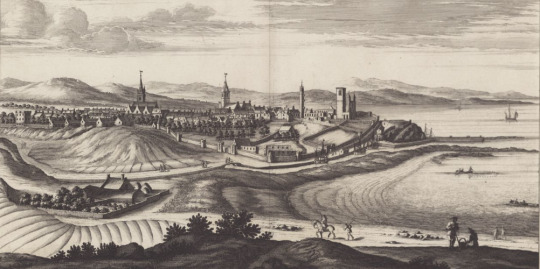

(John Slezer’s engraving of the prospect of St Andrews, c.1693. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence, with the permission of the National Libraries of Scotland)

On 3rd February 1414, papal bulls which confirmed the privileges of a new university finally arrived in the cathedral city of St Andrews. Several days of celebration followed, marking the formal establishment of Scotland’s first university, an institution which is still in existence today.

For most of the Middle Ages, Scots who aspired to study at university had to travel outwith the kingdom. Although Scottish students travelled all over Europe, initially they favoured the English universities of Oxford and Cambridge, at least before the outbreak of the Wars of Independence. Although some still crossed the border in pursuit of knowledge afterwards, most Scots then turned to continental universities: chiefly Paris, but also Orleans, Louvain, Bologna, Cologne, and others. Thus the small number of Scots who attended university gained a distinctly international outlook and exposure to the latest new ideas. However by the late fourteenth century some Scottish clergymen were increasingly convinced of the need for a Scottish university. Foreign travel was dangerous and expensive, and there were also political obstacles such as the ongoing Hundred Years’ War between England and France. Then came the Great Schism of 1378, when first two, then three different men set themselves up as pope in opposition to each other. Various mediaeval kingdoms declared their support for one or other of the rival popes and this was often dictated by political allegiance- for instance England supported the popes in Rome while Scotland supported the Avignon popes. But when the French abandoned their allegiance to the Avignon claimant Benedict XIII in 1408, the clergy of France and Scotland found themselves on opposite sides, making things difficult for Scottish students at French universities.

Something had to be done. Accordingly, in 1410, a small group of men gathered in the cathedral city of St Andrews in Fife, and began offering lectures on subjects such as theology, canon law, philosophy, and logic. Their choice of location might seem strange to 21st century eyes, but in the early fifteenth century St Andrews was the seat of Scotland’s most important bishop, and a major pilgrimage centre, and so the burgh was already home to many learned clerics. The first group of teachers at the embryonic university included Richard Cornell, a doctor of canon law and archdeacon of Lothian; William Stephenson, later Bishop of Dunblane; John Scheves; John Litstar; John Gill; William Croyser, later archdeacon of Teviotdale; and Master Laurence of Lindores, who was already the pope’s inquisitor of heretical pravity in Scotland. These early professors received the blessing of Henry Wardlaw, bishop of St Andrews, who issued a formal charter of privileges in 1412. However, to become a true university, St Andrews would have to obtain a papal bull confirming these privileges and establishing it as a recognised centre of higher education. A campaign for papal approval was soon underway and assistance was even sought from the nineteen-year-old King James I, then a prisoner in England. Together Bishop Wardlaw and the King of Scots wrote to the pope (or antipope?) Benedict XIII, requesting that the fledgling school at St Andrews be formally erected into a university.

(A fourteenth century depiction of antipope Benedict XIII, in Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. lat. 1777, fol. 1r. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Finally, on 28th August 1413, at Peñiscola in the kingdom of Aragon, Benedict XIII confirmed the privileges of the new university in not one, but six papal bulls. The first referred to the petition recently submitted, outlining some of the arguments the bishop and king and had made to support their request, such as the dangers of war and captivity and the suitability of St Andrews as a site for a university. Because of this, as well as the ‘singular devotion’ which the king and his realm had shown, and ‘considering also the peace and quietness which flourish in the said city of St Andrews and its neighbourhood, its abundant supply of victuals, the number of its hospitii and other conveniences for students, which it is known to possess’, Benedict agreed to their request. The first bull therefore established the university and empowered it to grant degrees. The second bull permitted any Scot who held a benefice to study and teach at the university, without losing any revenue from the benefice, so long as they appointed competent vicars to look after their flocks. The third bull covered much the same ground as the second, but also charged the Abbot of Arbroath, the Archdeacon of Galloway, and the Provost of the collegiate church of St Mary of the Rock (in St Andrews) with responsibility for ensuring that its provisions were upheld. The fourth bull recapitulated and confirmed the privileges already granted to the university by the bishop and prior of St Andrews, including the exemption from taxation given to all members of the university, and exemption from customs duties when buying and selling (and the same to any trades dependant on the university such as stationers, parchment-makers, transcribers, and servants). It also set out guidelines for resolving disputes between the university and the baillies of the burgh. The fifty bull entrusted the ‘care and inspection’ of the university to the bishop of Brechin and the archdeacons of Glasgow and St Andrews, while the sixth bull, referring to the difficulties faced by Scottish students who had to study in ‘countries infected with schism’, allowed those students to continue their studies and receive degrees at St Andrews instead. The year when these bulls were issued- 1413- is considered the true date of foundation for the university. But these six large documents still had to be brought home from Spain and it would take over five months for the precious bulls to arrive in Scotland, carried by a licentiate in arts named Henry Ogilvie.

When Ogilvie finally arrived in St Andrews on Saturday 3rd February 1414, bearing the long-awaited privileges, the clergy and people of the burgh exploded in celebration. The fifteenth century historian Walter Bower was a canon of St Andrews Cathedral at the time and included an eyewitness account of the proceedings in his ‘Scotichronicon’. As soon as the news of Ogilvie’s arrival became known, the air filled with a joyful cacophony as the bells of every church tower in the burgh rang out to welcome him. On the following day, which was a Sunday, the bulls were formally presented to Bishop Wardlaw in the packed refectory of the cathedral priory. The documents were then read aloud, following which strains of the familiar Latin hymn ‘Te Deum Laudamus’ echoed through the cathedral as the assembled clergy and canons processed to the high altar singing. There the bishop of Ross, Alexander de Waghorn, led the community in the versicle of the Holy Spirit (apparently a call and response type invocation to the Holy Spirit), and the collect Deus Qui Corda (a common prayer often associated with the ordination of priests and the attestation of relics). The clergy then spilled out of the cathedral precinct into the town where they celebrated for the rest of the day, drinking wine and setting up bonfires in the streets. A day of rest followed on the Monday, but the festivities continued on Tuesday the 6th, when a solemn procession and mass were organised to coincide with the feast of the burgh’s relics. This time, the bishop of Ross preached a sermon and the prior James Bisset celebrated the mass of the Holy Spirit. Walter Bower claimed that the beadles counted over four hundred clerics and monks taking part in the procession, ‘together with an astonishing crowd of people.’ Decades later, Bower still recalled the festivities with a sense of awe:

‘Who can easily give an account of the character of that procession, the sweet-sounding praise of the clergy, the rejoicing of the people, the pealing of the bells, the sounds of organs?’

When the celebrations died down, the growth of the new university continued apace. Eleven bachelors graduated that year, most having studied elsewhere, but the university found new students of its own quickly enough. By modern standards student numbers remained small, and the early university had no permanent buildings of its own until the mid-fifteenth century. For the rest of the Middle Ages it remained mainly a first degree institution, with most students who wanted to continue their studies beyond Masters level still opting to travel abroad. But there is no doubt that the establishment of Scotland’s first university was an important development in a rapidly changing world. Unlike certain other institutions of its time it has lasted the ages, surviving not only James I’s attempts to have the early university moved to Perth in the 1420s, and the foundation of its rivals at Glasgow (1451) and Aberdeen (1495), but also the threat of English attack during the Rough Wooing, the disturbances of the Reformation and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and the decay of the eighteenth century. The cathedral and castle lie in ruins, but because of its university (and golf), the town of St Andrews is still known throughout the world today.

(John Geddy’s map of St Andrews, c.1580. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence, with the permission of the National Libraries of Scotland)

Selected Bibliography:

- ‘Scotichronicon’ by Walter Bower, Abbot of Inchcolm. I used volume 8, in the version edited and translated by D.E.R. Watt.

- ‘Report of the Royal Commission appointed to enquire into the Universities of Scotland’, vol. 3. This includes copies of the original Latin papal bulls- an English translation can be found in C.J. Lyon’s ‘History of St Andrews’.

- ‘Acta Facultatis Artium Universitatis Sanctiandree’, vol. 1, edited by A.I. Dunlop

- ‘The Beginnings of St Andrews University’, by J. Maitland Anderson, in the Scottish Historical Review, vol. 8, no. 32 (July 1911)

- ‘James I of Scotland and the University of St Andrews’, by J. Maitland Anderson in the Scottish Historical Review, vol. 3, no. 11 (April 1906)

- You can view an image of one of the original papal bulls here, courtesy of the museum and library of the University of St Andrews

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#mediaeval#University of St Andrews#fifteenth century#1410s#Late Middle Ages#St Andrews#Fife#university#education#culture#Henry Wardlaw Bishop of St Andrews#James I#Benedict XIII (antipope)#Laurence of Lindores#William Croyser#Henry Ogilvie MA#Alexander de Waghorn#James Bisset prior of St Andrews#Walter Bower#Scotichronicon#religion#Great Schism#Christianity#Catholicism#celebrations#festivities#historical events

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

15th July 1445 saw the death of Joan Beaufort, wife and Queen Consort of James I.

Unlike most marriages of our Kings, and Royalty in general, this marriage was one that started with them falling in love.

Joan Beaufort was descended from kings. Through her mother she was a related to King Edward I of England and through her father related to King Edward III. During King James I of Scotland’s captivity in England, he was fortunate enough to meet Joan and fall in love with her. Joan was to be a worthy and able partner in helping James I rule his kingdom and as regent for their son, that's not to say it was that simple.

Joan’s family saw political advantage in her marrying the King of Scots and began working to persuade King Henry V to release James from his imprisonment. Henry V’s wife Katherine of Valois also applied pressure. On August 19, 1423, an embassy was sent from Scotland to negotiate his release.

On December 4, a treaty was finalised in London that included James’ marriage to Joan. A 60,000 merks ransom was to be paid by Scotland to England for the release in four instalments. Joan’s dowry of 10,000 merks was deducted from the ransom. Twenty-one Scottish hostages were sent to England as surety for the ransom, such was the times.

On February 2, 1424, Joan and James were married at the Church of Saint Mary Overy (now Southwark Cathedral on the south bank of the Thames in London). The couple attended festivities at Winchester Palace hosted by Joan’s uncle, Cardinal Henry Beaufort. They then started their journey north to Scotland. Scottish nobles met them at York to escort them home. On March 28 at Durham, James signed a pact for a seven year truce with England.

Joan and James were crowned at Scone Abbey on May 21, 1424 by Henry de Wardlaw, Bishop of Saint Andrews. By Christmas of that year, Joan gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Margaret. There is very little record of Joan other than the birth of her children. After Margaret was born, Joan had three more daughters before giving birth to twin boys Alexander and James in October of 1430. Alexander died shortly after but James survived, Joan had two more daughters after this.

In 1428 and in 1435, James went to visit the north of his kingdom and he made the nobles swear fealty to Joan in the event something happened to him. James I strove to maintain a centralised authority but it was extremely difficult.

Power in the Lowlands was stable but the Highlands and Islands maintained their autonomy. In foreign policy he demonstrated he would not follow English policies and renewed the Auld Alliance with France four years after his return from England.

The Auld Alliance survived and he secured the alliance with the marriage of his daughter Margaret to the French Dauphin Louis in 1436. Another daughter Isabella married Francis, Duke of Brittany in 1442 and daughter Eleanor married Sigismund, archduke of Austria in 1449 after her father’s death. All this secured Scotland’s international standing in the courts of continental Europe.

The pic is of James and Joan from a contemporary source.

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the middle of the Pandemic - can you get people to do anything you want?

You can also listen to this interview on a free app on iTunes and Google Play Store entitled 'Raj Persaud in conversation', which includes a lot of free information on the latest research findings in psychology, psychiatry, neuroscience and mental health, plus interviews with top experts from around the world. Download it free from these links. Don't forget to check out the bonus content button on the app.

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.rajpersaud.android.rajpersaud

https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/dr-raj-persaud-in-conversation/id927466223?

Introduction quoted from:

Annual Review of Law and Social Science 50 Years of “Obedience to Authority”: From Blind Conformity to Engaged

Followership

Alexander Haslam and Stephen D. Reicher

School of Psychology, University of Queensland, Australia and School of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of St. Andrews, United Kingdom

INTRODUCTION: WHAT WE THOUGHT WE KNEW ABOUT

“OBEDIENCE TO AUTHORITY”

In early 1961, residents of New Haven, Connecticut, were targeted via newspaper advertisements to take part in a psychology experiment at Yale University. Having been recruited, they arrived at a laboratory where they were asked by an experimenter to administer shocks to a learner whenever he made errors on a word-recall task. These shocks were administered via a shock generator and increased from 0 to 450 volts in 15-V intervals. The study was introduced as an investigation of the effects of punishment on learning, but in fact the researchers were interested in how far participants would be willing to follow their instructions. Would they be willing to give any shocks at all? Or would they stop at 150 V when the learner cried out, “Get me out of here, please. My

heart’s starting to bother me. I refuse to go on. Let me out”? Or at 300 V when he let out an agonized scream and shouted, “I absolutely refuse to answer any more. Get me out of here. You can’t hold me here. Get me out. Get me out of here”? Or would they continue to a maximum of 450 V (long after the learner had stopped responding)—a point labeled XXX on the generator? The answer was that of 40 participants, only 7 (17.5%) stopped at 150 V or lower, whereas 26

(65%) went all the way to 450 V. This finding suggested that most normal, well-adjusted people would be prepared to kill an innocent stranger if they were asked to do so by a person in authority. And in this finding the results appeared to bear testimony to the destructive and ineluctable power

of blind obedience (e.g., Benjamin & Simpson 2009, Lutsky 1995).

Stephen David Reicher

School of Psychology and Neuroscience - Bishop Wardlaw Professor

School of Psychology & Neuroscience

St Andrews

United Kingdom

Overview of Stephen Reicher's research interests from St Andrews University website

Broadly - the issues of group behaviour and the individual-social relationship. More specifically, my recent research can be grouped into three areas. The first is an attempt to develop a model of crowd action that accounts for both social determination and social change. The second concerns the construction of social categories through language and action. The third concerns political rhetoric and mass mobilisation - especially around the issue of national identity. Currently, I am starting work on a Leverhulme funded project (jointly with Nick Hopkins of Lancaster University) looking at the impact of devolution on Scottish identity and social action in Scotland.

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Text

Buncombe Co. NC Genealogies and Histories #northcarolinapioneers

Buncombe County Wills and Estates

Buncombe county was formed in 1791 from parts of Burke County and Rutherford Counties. It was named for Edward Buncombe, a colonel in the American Revolutionary War, who was captured at the Battle of Germantown. The large county originally extended to the Tennessee line. Many of the settlers were Baptists, and in 1807 the pastors of six churches including the revivalist Sion Blythe formed the French Broad Association of Baptist churches in the area. In 1808 the western part of Buncombe County became Haywood County. In 1833 parts of Burke County and Buncombe County were combined to form Yancey County, and in 1838 the southern part of what was left of Buncombe County became Henderson County. In 1851 parts of Buncombe County and Yancey County were combined to form Madison County. Finally, in 1925 the Broad River township of McDowell County was transferred to Buncombe County.

Genealogy Records available to members of North Carolina Pioneers

Images of Will Book B, 1869 to 1899 Names of Testators:

| Alexander, George C. | Allen, Autonia | Baird, Eliza T. | Baird, Mary A. | Banks, H. H. | Banks, S. M. | Bell, Thomas | Brand, Hann | Brank, Joseph R. | Brittain, George W. | Brittain, William | Brookshire, Lula | Brown, Nathan | Brown, Nathaniel | Brown, William H. | Buchanan, W. A. | Burnett, Elrige | Burnett, James M. | Burnham, Hiram | Buttam, William | Calloway, Sarah Ann | Carter, Daniel W. | Chambers, William | Chambers, William Sr. | Chunn, Joseph | Clark, Jesse | Cochran, Harriet | Cole, Joel | Coleman, William | Conley, John | Crane, Mary Ann | Cunningham, E. H. | Cunningham, John W. | Curtis, B. J. | Daugherty, Lemuel | Davis, Asbery | DeBrull, Susanna | Duffield, Charles | Dula, Thomas | Edney, James M. | Edwards, Helen Maria | Eller, Adam | Eller, William | Embles, Joseph | Endley, James | Erwin, William A. | Frank, John | Freer, Carolina | Frisbee, William | Garren, Marion | Green, Jeremiah | Green, Katherine | Hall, A. E. | Hampton, Levi | Hawley, Levi | Henderson, David | Henderson, L. D. | Henry, James L. | Herndon, E. W. | Herrick, Edwin Hayden | Hyatt, P. A. | Hyman, Ellen | Ingram, Louis | James, Silas | Johnson, A. R. | Johnson, Henry J. | Johnson, Rufus | Johnson, V. D. | Johnston, Hugh J. | Jump, William | Kennedy, John P. | Kimberley, Bettie | Lanning, John | Lanning, Rebecca | Lee, Stephen | Lenoir, Betsy | Litcomb, Margarett | Love, Lorenzo | Luther, Laura | Luther, Solomon | Lynch, Martha J. | McBrayer, William | McGill, Wardlaw | Mercer, Sarah Ann | Merrell, John | Merriman, Branch H. | Middleton, Henry | Miles, Levin | Miller, Henry | Miller, Peter | Moody, Mary Janet | Mordecai, G. W. | Morgan, David | Morgan, Noah | Morrow, Ebenezer | Murdock, Margaret | Murphy, Laura | Murray, Patience Marcella | Murray, Robert A. | Murray, William S. | Palmer, C. B. | Patton, Eliza W. | Patton, John E. | Penland, M. P. | Pinner, Hugh | Plummer, William G. | Polk, Thomas | Poor, John | Pullium, R. W. | Randolph, Mary | Rankin, W. D. | Ratcliff, M. J. | Reed, Jacob | Reed, William R. | Revis, W. C. | Reynolds, John | Reynolds, John D. | Richards, Charles B. | Roberson, James Alford | Roberts, James Riley | Roberts, Joshua | Roberts, M. | Roberts, Thomas O. | Rogers, Caroline M. | Roselee, Sarah | Rumple, Robert | Russell, W. H. | Saunders, Benjamin F. | Shackleford, P. C. | Sluder, J. E. | Sluder, John | Southee, Joseph | Smith, B. J. | Smith, F. A., Mrs. | Smith, James T. | Smith, J. H. | Smith, Owen | Smith, William A. | Stepp, Rachael | Stevens, Francis M. | Stevenson, Abraham | Stewart, John Curtice | Stroup, Nancy | Swain, Eleanor H. | Taylor, Robert J. | Wallack, Isadore | Weaver, Jesse R. | Weaver, John S. | Weaver, M. M. | Wells, J. R. | Whitaker, Henry | White, David | Woodcocke, J. A. | Woodfin, Eliza | Worth, Frederick | Young, Lewis

Images of Buncombe County Will Book C, 1887 to 1897 Names of Testators:

| Adams, Daniel D. | Adams, Julia W. | Alexander, George Newton | Arnold, Henry | Ashworth, Johnson | Austin, J. H. | Baird, Rebecca | Ballard, Caroline | Barker, Clarence Johnson | Blount, John Gray | Braunch, William George | Broesback, Anna | Brown, Daniel | Brown, Mary T. | Budd, Margaret Anderson | Call, John D. | Cameron, Paul | Carpenter, John | Carpenter, John (1911) | Carroll, John L. | Carter, Melvin Edmondson | Cathcart, William | Cathcart, William (1805) | Cathey, J. L. | Cawble, Jacob | Chambers, John C. | Chapman, S. F. | Chapman, Verina | Christiansen, George | Cole, Ann B. | Clark, Adger | Clemmons, E. T. | Cortland, Mary Katharine | Croft, Sarah Ann | Cummins, Anson W. | Cushman, Walter S. | D' Allinges, Baron Eugene | Davidson, Thomas F. | Dobbins, Mary | Ducket, Margaret | Frady, J. A. | Frady, John | Fulton, Mary | Garren, David | Gask, B. S. | Goodrum, Maria | Haggard, Elliott | Hendry, Theodore | Henry, Robert | Hill, Wylie | Hines, W. F. | Israel, Levina | Johnson, Julius | Johnston, Andrew H. | Johnston, William | Jones, R. L. F. | Lagle, W. S. | Lindsey, Andrew J. | Mason, Lavinia | McHemphill, William | McMerrill, John | McNeal, Florella | McRee, C. E. | Melke, Arthur | Meyers, Sarah Ellick | Meyers, Sarah Thayer | Miller, George | Miller, Joseph M. | Moore, Harry V. | Murdock, David | Murray, J. L. | Neilson, M. A. | Peller, Joseph | Penland, William M. | Pinketon, James | Pinner, Leander | Powell, Martha J. | Price, Linus | Randall, James M. | Randall, Matthew | Reed, John Sr. | Reeves, John | Reynolds, Alice | Roberts, J. R. | Schultz, Andrew | Spivey, B. F. | Starnes, Jacob | Summer, Richard | Swain, Eleanor H. | Tagg, Marcellus J. | Tennent, Charles | Tennent, Marianne | Tompkins, Frederick W. | Washington, Julia | Weaver, M. M. | Webb, S. W. | Weber, August | West, George W. | Whitaker, L. W. | White, Edward S. | Wilson, Alfred

Images of Will Book A, 1831 to 1868 Names of Testators:

| Alexander, James | Alexander, James C. | Alexander, Lorenzo D. | Anderson, William | Arrington, James | Ashby, John | Ayres, C. | Baird, B. | Baird, Hannah | Ball, Joel | Bell, Thomas | Boyd, James | Brevard, John | Burlison, Edward | Call, John | Candler, Zachariah | Carter, Jesse | Carver, Joseph | Chambers, John | Cochran, Harriett | Cochran, William | Cole, Jesse | Cole, Joseph | Collins, Riddick | Cooke, Joseph | Curtis, Benjamin | Curtis, Delilah | Dale, Richard | Davidson, Samuel | Davidson, Sophronia | Davis, John | Davis, Margarett | Davis, William | Dillingham, Absalom | Dilliingham, Rebecca | Dougherty, John | Doweese, Garrett | Edmons, Elizabeth | Edwards, David | Edwards, Isham | Eller, Mary | Flagg, William | Fortner, John | Foster, Mary | Foster, Thomas | Foster, Thomas | Garmon, William | Gaston, Thomas | Gentry, John | Gilbert, Daniel | Gill, Rebecca | Gillispie, Francis | Goodlake, Thomas | Gousley, Hugh | Grantham, Joseph | Green, Jeremiah | Gudger, William | Harper, Lot | Harris, Able | Hawkins, Rachel | Henry, Dorcas | Holcombe, Obediah | Hutsell, Elizabeth | Ingle, Elizabeth | Ingram, Thomas | James, Thomas | Jarrett. Fanny | Johnston, A. H. | Jones, Ebed | Jones, George W. | Jones, Thomas | Jones, Wiley | Jones, William | Killian, William | King, Jonathan | Lackey, John | Lane, Sarah Ann | Livingston, John | Low, Stephen | Lowrey, James | Lusk, John | Marson, William | Martin, Jacob | McBrayer, James | McDonnell, William | McDowel, Athan | McFee, John | Means, John | Merrell, Benjamin | Merrell, Jesse | Merrell, John | Morgan, James | Morrison, John | Murdock, William | Nelson, William | Owens, John | Palmer, Jesse | Palmer, J. T. | Patton, Ann | Patton, James A. | Patton, James | Patton, James W. | Patton, John | Peavy, Bartlett | Peek, Jesse | Penland, John | Pinner, Burrell | Pitman, Thomas | Plemans, Peter | Poor, Isaac | Porter, Edmund | Porter, William | Potter, James | Powers, Brady | Prestwood, Johnathan | Reaves, Malachi | Reed, Eldred | Reed, Jane | Reed, Peter | Reynolds, Joseph | Roberts, John | Robeson, Andrew | Robeson, Jonah | Robeson, William | Robird, Robert | Rogers, Andrew | Saddler, John Roberd | Saunders, Benjamin | Sharp, Thomas | Smith, James M. | Smith, James M. (1864) | Spier, Alexander | Stepp, Silas | Stockton, Richard | Summers, Richard | Thrash, Valentine | Turner, James | Vance, Priscilla | Warren, Robert | Weaver, J. T. | Wells, Leander | Wells, Thomas | West, Henry | West, John | Whitaker, John | Whitaker, William | White, Ann | Whitesides, John B. | Whitmire, Christopher | Williamson, Elijah | Williamson, Elizabeth | Williamson, Richard | Willis, John | Wilson, John | Woodfin, J. W. | Wyatt, Shadrack | Young, John | Young, Rosannah | Young, Sarah

Indexes to Probate Records

Wills 1831 to 1868; Wills 1868 to 1899; Wills 1887 to 1897

Find your Ancestors Records on North Carolina Pioneers

SUBSCRIBE HERE

via Blogger http://ift.tt/2gOnCGA

1 note

·

View note

Text

Improving data availability for brain image biobanking in healthy subjects: practice-based suggestions from an international multidisciplinary working group.

PubMed: Related Articles Improving data availability for brain image biobanking in healthy subjects: practice-based suggestions from an international multidisciplinary working group. Neuroimage. 2017 Feb 13;: Authors: BRAINS (Brain Imaging in Normal Subjects) Expert Working Group, Shenkin SD, Pernet C, Nichols TE, Poline JB, Matthews PM, van der Lugt A, Mackay C, Lanyon L, Mazoyer B, Boardman JP, Thompson PM, Fox N, Marcus DS, Sheikh A, Cox SR, Anblagan D, Job DE, Alexander Dickie D, Rodriguez D, Wardlaw JM Abstract Brain imaging is now ubiquitous in clinical practice and research. The case for bringing together large amounts of image data from well-characterised healthy subjects and those with a range of common brain diseases across the life course is now compelling. This report follows a meeting of international experts from multiple disciplines, all interested in brain image biobanking. The meeting included neuroimaging experts (clinical and non-clinical), computer scientists, epidemiologists, clinicians, ethicists, and lawyers involved in creating brain image banks. The meeting followed a structured format to discuss current and emerging brain image banks; applications such as atlases; conceptual and statistical problems (e.g. defining 'normality'); legal, ethical and technological issues (e.g. consents, potential for data linkage, data security, harmonisation, data storage and enabling of research data sharing). We summarise the lessons learned from the experiences of a wide range of individual image banks, and provide practical recommendations to enhance creation, use and reuse of neuroimaging data. Our aim is to maximise the benefit of the image data, provided voluntarily by research participants and funded by many organisations, for human health. Our ultimate vision is of a federated network of brain image biobanks accessible for large studies of brain structure and function. PMID: 28232121 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher] http://dlvr.it/NV1bHq

0 notes

Text

Together the Wardlaw brothers are roughly 14% of the Central Coast roster

On these pictures there are respectively: Xander (89), Connor (44), Aidan (27) and Callum (86)

#‘and a goal by wardlaw!!!!’#dude which one :/#alexander wardlaw#connor wardlaw#aidan wardlaw#callum wardlaw#central coast rhinos#aihl

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

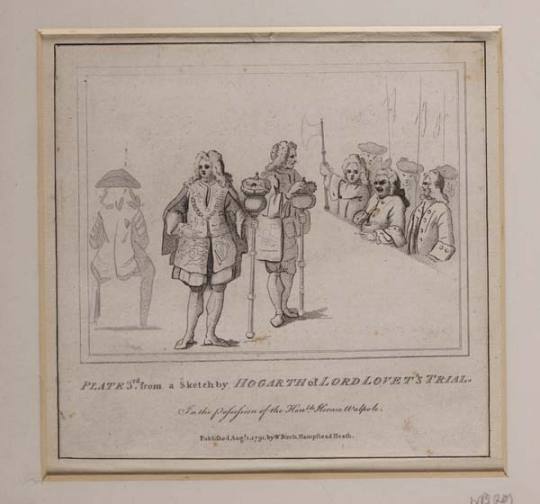

On 9th April 1747 Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, the leading Scottish Jacobite rebel was beheaded on Tower Green.

A longer post than normal from me as in my opinion Simon Fraser was one of the most interesting characters in Jacobite history. A man of contrary, he was known to be very kind to the lesser clansmen taking a paternal interest in their affairs. A quote regarding him says that...."Generally he had a bag of farthings for when he walked abroad the contents of which he distributed among any beggars whom he met. He would stop a man on the road; inquire how many children he had; offer him sound advice; and promise to redress his grievances if he had any" In his own estimate, he took care his clansmen were ‘always well-clothed and well-armed, after the Highland fashion, and not to suffer them to wear low-country clothes’ Lovat was also a brute of a man forcing a young woman into marriage and raping her in an attempt to legitimise the union. Lovat has become more well know lately thanks to Outlander, where in their world he is grandfather to the main protagonist Jamie Fraser and played brilliantly by the fine Scottish actor Clive Russell. Back in the real world he has been in the news only this year, I shall cover that at the end of this post.

Born in 1667 into the ancient clan who fought with distinction in the Wars of Independence – Sir Simon Fraser was one of the co-victors of the Battle of Roslin and his sons were close friends of Robert the Bruce, Alexander marrying Bruce’s sister Mary – Simon was the second son of Thomas Fraser of Beaufort who was closely related to Lord Hugh Fraser of Lovat, chief of clan Fraser.

Simon became his father’s heir when his elder brother was killed fighting alongside Bonnie Dundee against the forces of King William III at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689. He was still nowhere near being clan chief, however, and took himself off to Aberdeen University from which he graduated in 1695. Lord Hugh Fraser, the 9th Lord Lovat, was a weak man who unexpectedly signed over the clan leadership to Simon’s father in 1696.

Lord John Murray, Earl of Tullibardine and the most powerful man in Scotland, disputed the succession and fell out spectacularly with Simon in Edinburgh. The young Fraser hothead duly went north to Castle Dounie to try and persuade Hugh’s widow Amelia to give him the hand of her daughter, also Amelia, in a dynastic marriage that would seal his succession. Tullibardine was having none of it and moved his niece to the Murray stronghold, Blair Castle, where he planned to marry her off to Alexander Fraser, heir to the Lordship of Saltoun.

Simon retaliated by kidnapping Alexander and frightening him away, and to make matters worse in October, 1697, he went back to Castle Dounie and forced the widow Amelia into a sham wedding, raping her to consummate the “marriage”.

Tullibardine ensured Simon and his father were declared outlaws and when old Thomas died in 1699, Simon was unable to legally claim his title as 11th Lord Lovat which later passed to one Alexander Mackenzie who had legally married the younger Amelia.

Simon Fraser somehow managed to persuade King William that he was no threat, despite having his own personal army, and he was pardoned in 1700, only to be declared an outlaw again the following year over the forced marriage and rape.

Simon went off to the court of the Stuarts in France where he devised the plans that were eventually used in the 1715 and 1745 uprisings. Long before the former, however, Simon was double dealing, giving Queen Anne information about the plans of James, the Old Pretender. He was found out and King Louis XIV clapped him in jail for three years.

Even after he was released he was prevented from travelling to Scotland and thus missed the Act of Union which he opposed.

Still desperate to get his Lovat title and the chieftainship of his clan back, Simon sided with the forces of the new King, George I, during the ’15, and was given back his title as a reward, with Alexander Mackenzie imprisoned for being a Jacobite. The two men would fight in the courts for the next 15 years as to who was entitled to the income of the estate. Simon eventually won and spent his time building up the Fraser estates and wealth, even taking command of one of the Independent Companies of Highland soldiers established by the Hanoverian regime – the Fraser Highlanders.

As I said early Fraser was a man of contrary and to me was very like "Bobbing John" The Earl of Mar another Jacobite who a tendency to shift back and forth from faction to faction, no sooner had Fraser built up this "Hanoverian" army that he started openly campaigning for the restoration of the Stuarts. The Government responded by cancelling his military role.

When Bonnie Prince Charles landed in Scotland he was still playing games.

He allowed his sons to fight for the Stuarts, but stayed at home himself “loudly lamenting the wilful disobedience of children,” as Sarah Fraser has put it. Lovat did meet Charles, however, and expressed his anger at the lack of “siller” which he knew would be necessary for a successful campaign. They met again after Culloden, at which Clan Fraser fought bravely and suffered many casualties, and Lovat advised the prince to get away and re-form his forces. Charles fled through the heather, as we know, and made it to France while anyone associated with the Bonnie Prince was hunted down. The Duke of Cumberland’s troops were not taking any more games from Fraser and burned Castle Dounie.

Lovat managed to make it to Loch Morar but was captured there while hiding in a hollow tree. Although approaching his 80th birthday, The Fox was taken south to London.

He pled not guilty but his trial was a formality and he must have know his fate would be the same as previous nobles, the Earls of Kilmarnock, Balmerino and Derwentwater who were executed for treason the previous year.

At his trial, ever the Fox he insisted strongly upon his affection for the reigning family. Such were the characteristics of Simon Fraser, but of course he was found guilty the sentence, hanging, drawing and quartering was commuted later to a mere beheading by the King.

In a way, Lovat had the last laugh. Newspapers and pamphlets of the time recorded that as he was led out to the scaffold on Thursday, April 9, 1947, a wooden stand that had been erected near the Tower to seat crowds eager to see the execution collapsed sending hundreds plunging down. At least nine people died and dozens were injured, which amused Lovat – the phrase ‘laughing your head off’ is said to date from that event.

According to a woodcut print made on that fateful day, Lovat “with some composure laid his head on the block which the executioner took off with a single blow.”

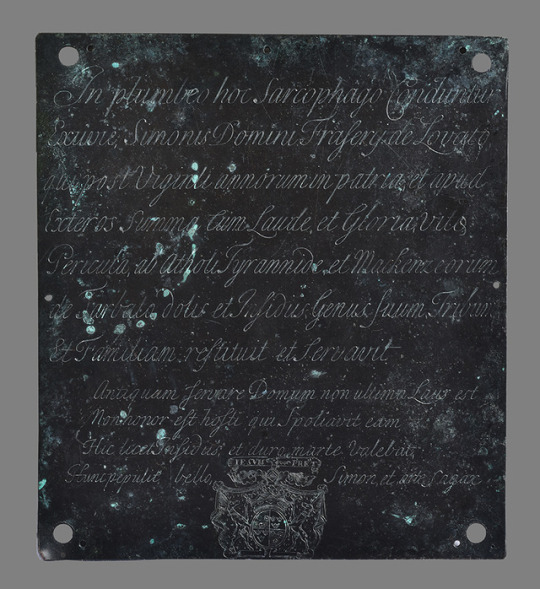

As I mentioned at the top Lovat has been in the news lately, Simon had requested burial at the family mausoleum at Wardlaw near Inverness and the government initially agreed but changed its mind thinking his body could become a rallying point for further trouble. He was therefore buried in the floor of the chapel within the Tower of London, St. Peter ad Vincula. The chapel was refurbished in the 19th century and the floor was relaid. One of the coffins uncovered during the works had the nameplate of ‘Lord Lovat’. The names of those found are now recorded on a plaque on the wall of the chapel.

Fraser folklore, and written in several books says that his body was spirited away from London, the stories even go so far as to name the boat ‘The Pledger’ that sailed north to The Beauly Firth, where he was taken to the family mausoleum, there is even a plaque in the crypt that reads “In this coffin are laid the remains of Simon Lord Fraser of Lovat who, after twenty years in His own Land and abroad with the greatest distinction and renown, at the risk of his own life, restored and preserved his race, clan and household from the tyranny of the Athol and the treacherous plotting of the Mackenzies of Tarbat. To preserve an ancient house is not the greatest credit. Nor is there any honour for the enemy who despoiled it. Although that enemy was strong in his plotting and unrelenting warfare, yet Simon who was also skillful and cunning defeated him in war."

Last year the headless skeleton inside the coffin was exhumed to be examined by experts from the University of Dundee in January this year they announced that the bones in the coffin did not belong to Simon Fraser, but to a young woman. So it looks like his body did end up rotting in The Tower's Chapel.

To understand how big Lovat's trial and execution were I have posted a number of pics all dating back to the eighteenth century, and the plaque from the Crypt at Wardlaw.

30 notes

·

View notes

Link

On 12th February 1424 James I married Lady Joan Beaufort.

King Robert III of Scotland had attempted to send his younger son James Stewart to France to guard him from the machinations of his uncle, Robert, Duke of Albany, but the twelve year old James was captured by English ships just off Flamborough Head. When King Robert died soon after on 4th April, 1406 James succeeded to the Scottish throne as James I. While the young King grew to manhood in English captivity, his ambitious and self-serving uncle was appointed Regent and Governor of Scotland in his absence and exhibited no haste in securing his nephew's release.

James received an education and traveled with the English court, where he learned much about government and administration, which helater put intopractice when he returned to his native Scotland. Joan met James I during his English captivity, the couple had known each other from at least 1420. James fell in love with Joan, she is said to have been the inspiration for his famous long poem, The Kingis Quair, written after he saw her from his window in the garden. James negotiated a release from captivity the previous year, the English favoured his alliance with the Beauforts which it was hoped would continue Scotland's alliance with the England, rather than their traditional ally France. Joan's dowry of 10,000 merks was subtracted from the substantial ransom of 60,000merks the Scots had to pay for the return of their king. James and Joan were married on 12 February 1424 at St Mary Overie Church in Southwark. The newlyweds attended festivities at Winchester Palace hosted by Joan's uncle, the powerful Cardinal Henry Beaufort. They then started their journey north to Scotland.

Joan was crowned queen of Scotland on 2 or 21, May at Scone Abbey by Henry de Wardlaw, Bishop of Saint Andrews. James, unlike his father, possessed a strong and resolute character, and was determined to crush the threat posed by the power of the Albany Stewarts and promptly confiscated their estates. Murdoch Stewart and his two sons were executed on Castle Hill, at Stirling. In 1429, Alexander Macdonald, Lord of the Isles, was captured after burning and pillaging in the Scottish Highlands. Dressed as a penitent, he was compelled to appear before the high altar in Holyrood Abbey. In a pre-staged scene, Joan pleaded with her husband for his life. This allowed James to save face while exercising mercy.

The couple produced eight children, seven of whom survived to adulthood, they included the future James II and his twin who died in infancy, Alexander Stewart, Duke of Rothesay who was the heir apparent to throne and would have been Alexander IIII had he lived.

More on Joan Beaufort at the link below

http://www.medievalists.net/2014/02/joan-beaufort-queen-scotland/

29 notes

·

View notes