#also a character that wants peace and order but actively pursues violence ensuring she will never truly have those things bc of her nature

Text

Asuka is a tragic figure, a figure of mystery, a wild card, all because the only thing she wants in life is peace and quiet for herself and to feel in control- yet her secret heritage that may be hidden from her for her own protection and the reality that life is unpredictable and will go on with or without you keep ruining that delusion, that vision of how the world is meant to work to her, and she suffers regardless of what she wants, what she does, and how little she understands anything

She was born into a family preaching peace and balance and order while being a creature of violence, and puts a dozen mental locks and excuses over this truth to justify giving into her impulse for fighting by pretending she's justice when she does it

She keeps trying to build a place of safety but she's using sand and life is a wave that destroys, yet she stubbornly persists rather than give up, not drowned to the point of self centered suicidal loathing like Jin- there's contrast, where Jin is cloaked in death Asuka stubbornly clings to life and humanity as a normal person in a terrifying world

She's not a fucking narrative clone for Jun's own purpose, Asuka's purpose must be determined by Asuka herself

#tekken#Jin is born of two worlds Jun walks between two worlds Asuka is at the crossroads of two worlds#Jin is broken by it Jun traded part of her humanity to reconcile it and now Asuka has to accept it yet persist- she is always persisting#that's her strength that no matter what she's always still herself#'For being so very Y o u' as Lili told her bc she sees it#she's an interesting character BECAUSE she's not Jun and she's not Jin and she's not aligned with them entirely#stop waiting for her to be something she's not#also i think it's GOOD she doesn't know everything or everyone in her family bc that builds mystery and suspense#it gives everything a tension in the background for when the normalcy charade will be broken by the bigger family drama catching up w her#what's happening to the Mishimas should be something no one is dragged into yet the one family member who's the least connected#is going to run out of time at some point and get hit by that trauma anyway and she doesn't even Know it's coming for her eventually#isn't it fucked up. how everything catches up with you in the end#and you won't even understand it until it's too late ie. her involvement in T8 global war now#also a character that wants peace and order but actively pursues violence ensuring she will never truly have those things bc of her nature#AND she's already been traumatized by T5 Feng and T6 Jin that just makes her retreat to seeking comfort in detachment- in the familiar#which only prolongs her avoiding the world outside what she can control- and then Lili won't let her live in ignorance not to punish her#but bc she wants to help her bc the Mishimas have already put their claws in Lili- they won't catch Asuka off guard#what is it with people sanitizing the messiness and humanity characters represent in favor of 'If they just acted logically the way I want#then they'd solve the entire story 1 2 3 and we'll have everything wrapped up easy' THAT'S NOT A STORY THAT'S A MATH EQUATION#FEEL SOMETHING INSTEAD OF ALWAYS NEEDING TO SOUND SMART AND HAVE PERFECT ANSWERS YOU STUPID FUCKS#IN TRYING TO MAKE EVERYTHING HAVE A PERFECT SOLUTION YOU'VE LOST SIGHT OF WHAT'S IN THE TEXT#AND ALSO ASUKA BEING VIOLENT BUT STILL CARING ABOUT PEOPLE AND DOING GOOD DESPITE IT#and AsuLili is about two similar people who've been traumatized finding safety in each other once they put down the trauma responses#this is all in line with T8's tagline of Face Your Fate btw this is literally what was always coming finding you & you face it

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Love someone.”

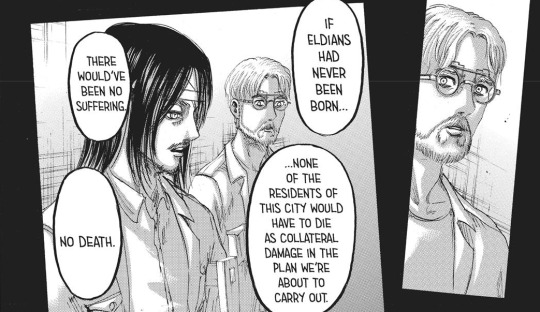

One of the recurring themes in this manga, more prevalent during recent chapters now more than ever, is the reality that hatred only breeds more hatred and continues the cycle of violence, oppression and prejudice.

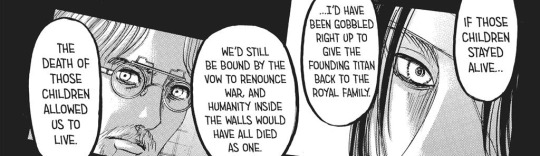

Kruger was a man who was fueled by his hatred for Marley. He grew up only to find himself torturing, killing and titanizing other Eldians, all in the name of the eventual restoration of Eldia. He helped to condition Grisha, who was also fueled by his deep hatred for Marley, to believe that there was a chance to turn the tables and restore Eldia by overthrowing Marley. In the end, the only results either of these two bore was more death and hopelessness. Grisha realized he couldn’t even be a suitable husband and father. His hatred took over every facet of his life and it failed him in the end.

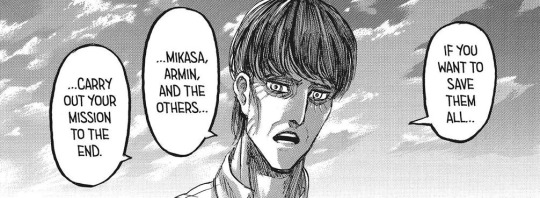

Kruger, in his final moments, tells Grisha to love someone. It didn’t matter who; his wife, his child, even just any random person. If he doesn’t learn to love - to truly love - history will only continue to repeat itself. He goes on to tell him that this is the only way to save Mikasa, Armin and the others. He must carry out his mission to the end.

And I think it’s so important that we are shown several times during the Grisha files how Eren’s memories and actions have become intertwined with Grisha’s and Kruger’s. It’s almost like this is a three-way conversation without them even knowing it.

Like his father and Kruger before him, Eren found himself fueled by hatred and revenge. It was the primary thing on his mind from the moment Armin showed him that book and he realized he wasn’t free-

- and it was only exacerbated when his hometown was destroyed and his mother was killed in front of his eyes.

Early in the series we are introduced to Eren’s very black-and-white view of the world. Those who deny others their basic freedom are no better than animals, that they don’t matter, and Eren had no qualms in killing those men for what they did to Mikasa and her family. But, you see, his act of cruelty toward these “animals” was born from a place of care and concern for the life and freedom of an innocent girl he’d never met. And this act of cruelty led to one of the most beautiful acts of care in this series.

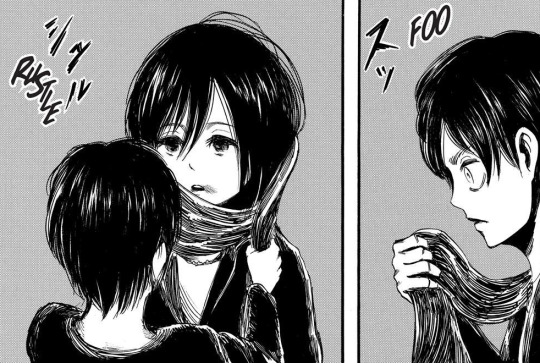

His actions saved a little girl from a life of enslavement. She said she was cold, and so he chose to give her warmth. When she tells Eren her feelings later in a moment of finality and hopelessness, he rejects their death and promises to give her this warmth and care as many times as she wants him to.

Eren loves her.

He defied his superiors in an effort to save Armin’s life. He lamented that his own hatred was all that he had, and admired Armin still for having his innocent dreams to push him forward. He was desperate to not have to let Armin go if it was an option, and prioritized the ability for Armin to achieve his dream of seeing the ocean.

Eren loves him.

Even if it gets in the way of Eren being able to accomplish the change he wants to see, he is firm in that he will not sacrifice Historia’s life. He stays silent for as long as he can in order to protect her from a cruel fate, no matter if that hinders the ability for Eldia to move forward.

Eren loves her.

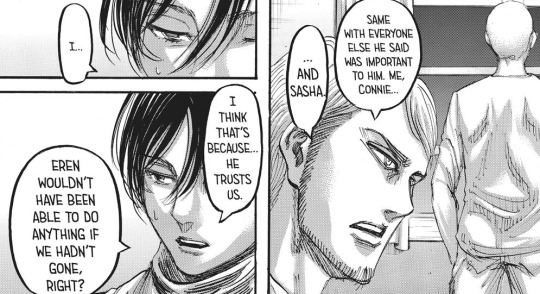

Eren as a character embodies the duality of the beauty and cruelty that all humans are capable of. Although he believes that he is fueled only by his hatred, I think that it is apparent he is fueled by his love for his friends. But I think what is ultimately going to define his character and the conclusion of his arc is whether he allows his love to grow and help shape the future into something better, or if he will allow his hatred to consume him and continue the cycle of destruction and oppression.

As the central and title character of the series, I feel that the conclusion of his journey and his struggle will shape the overall theme and message of this series. Because of this, and because of the many times that hatred is declared as the reason progress and positive change is inhibited, I believe that ultimately the love between Eren and his friends will win out, preventing the future from cycling through the same negative actions over and over. Characters like Gabi and Falco will benefit from this as the next generation, and his friends will be able to find their own peace as a result of Eren’s actions, no matter how questionable they may be at the current moment.

The only way he can save Mikasa and Armin is by carrying out his mission to the end.

His actions currently may be cruel, but all of the evidence points to the reality that his actions are all set in place as a means to an end to protect the people he loves dearly. This is what drives him more than anything.

The many questions floating around fandom right now is whether Eren intends to crush the world with the rumbling, whether he will sever the Eldians’ access to paths, whether he will sacrifice himself to save his friends, among many other ideas and theories. I have a theory - I think that it’s possible Eren did once consider using the full-scale rumbling, but has since changed his mind.

Eren admits himself that he once saw everyone across the ocean as his enemy. The world wants the island destroyed, and Grisha’s memories were filled with hatred from both Grisha and Marley. It was the only natural conclusion for Eren to come to. But when he crossed the ocean to meet his brother, he realized that it’s not that black and white. Not everyone is an enemy. People are the same no matter where you go. Good and bad people exist all over, and it isn’t something that is defined by one’s race or even their actions. He learns to understand that Reiner didn’t attack Shiganshina that day because he’s a bad person or a heartless murderer - he was a brainwashed child.

Eren tells Reiner that they are the same. They’re pushed by their environment to act in cruel ways, as that’s the only way for them to move forward and pursue their goals.

Eren’s enemies in Liberio were the Marleyan military and the War Hammer Titan. He lamented that civilians were going to get caught up in the attack. Much like how Kruger accepted participating in the cruel fate of several hundreds of Eldians in his belief he’s doing the right thing, much like how Grisha allowed himself to slaughter children in order to ensure that stealing the Founding Titan wasn’t for naught, Eren here has to accept the casualties in Liberio for the benefit of the many. He realizes the pain and sorrow he’s about to inflict, but as regrettable as it may be, he feels he has no choice if Eldia is ever to become free. It’s very reminiscent of real world war.

It’s hot hatred fueling his actions here anymore. His personal goal is to protect his friends from the fate of titan inheritance, to free Paradis from the thumb of oppression, and I’d even argue after having spent a lot of time in Liberio, he hopes to free all Eldians from the cruel fate of existing in a world that detests them. He must commit atrocities such as the attack in the internment zone in order to accomplish these goals. If the friends he loves so much are ever to be truly free, he must become a “bad person.”

In Liberio, his mission is to bring Zeke back to the island and to find a way to stop this war before it can continue to take the life of his friends - in particular, before Historia has to be sacrificed to the curse of Ymir in order to maintain the dangerous deterrent that is the rumbling.

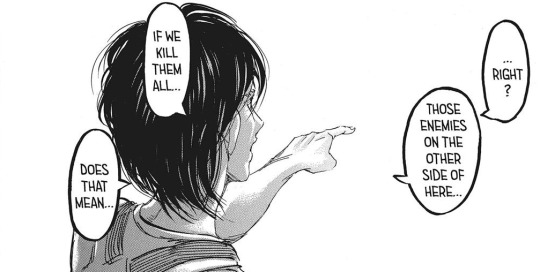

The only way to truly save his friends, to save the Eldian race, is to eliminate the titans. Eren intends to do this, and he firmly says so. This is the main reason why I subscribe to the theory that Eren’s endgame is to sever the Eldian paths from his people so that they no longer can become titans. It is the only true way for him to save his friends and his race. Although the prejudice wouldn’t disappear overnight, it’s a step in the right direction. At least they can’t be turned into monsters anymore. At least titan inheritance will no longer continue.

“Breeding and dying like livestock” will no longer be the way they have to live.

His actions are born from a place of concern and care for his friends and fellow Eldians.

How would crushing the entire world with the colossal wall titans “put an end to 2000 years of history under titan rule?” It would only perpetuate it further. This is why I believe this won’t be, or can’t be, Eren’s ultimate endgame. It continues the cycle of death, despair, fear and hatred.

So if it turns out his goal is simply to rewrite Eldian DNA to sever the paths, and not something more destructive and harmful such as activating the rumbling and eliminating the rest of the world, why must he push his friends away? Why is he treating them so cruelly?

Well....

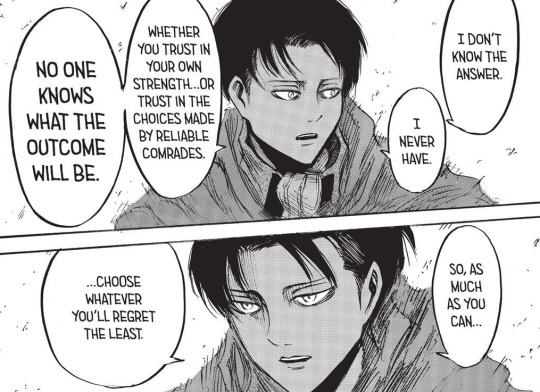

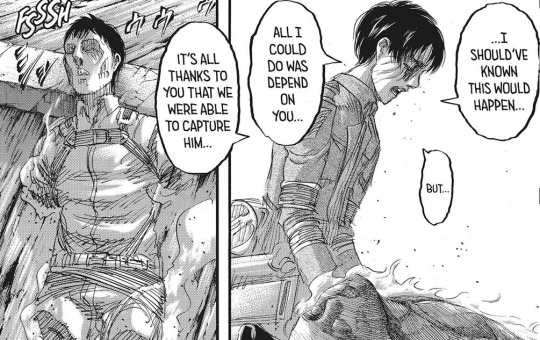

Time and time again, Eren’s trust in his loved ones and comrades has betrayed him. Someone always dies. The only times where he was able to save everyone was the times he allowed himself to believe in his own strength.

He knows that Mikasa and Armin in particular would follow him into hell if he asked them to. But Sasha’s death only reaffirmed to Eren that when he chooses to rely on his friends he will end up losing someone. And ever since he almost lost Armin during the retaking of Wall Maria, Eren can’t bear the thought of losing any more of his loved ones. He chose to believe in them one last time and Sasha died as a result. And like every time before, he surely blames himself. It doesn’t matter how carefully he plans something out, miscalculations are bound to happen and he has no power over this. He harshly learns to understand this in Liberio.

He loves these people and he’s unwilling to sacrifice them. And he feels like he can’t even trust them to stay alive if they continue to follow him down his path.

So how do you get those who would follow you into hell to stay away?

Hit them where it hurts. Don’t give them a reason to follow you anymore. Make them lose faith in you, make them question you, make them hate you, and they won’t die trying to protect you.

Want to make extra sure that they stay out of the line of fire?

Although he is using cruel methods to push his friends away, the fact of the matter remains that he cares about them. He’s taken no pleasure in hurting them or jailing them. But to him it has become necessary in order to protect them.

He loves them. It’s not about hating the enemy. It’s not about enacting revenge. It’s about protecting what he cares about, who he cares about, and ensuring them a future they can live freely in. Even if it means destroying himself and his ties to them in the process.

Destroying the world for the sake of the island will not bring his friends peace and prosperity, and it will not ensure a positive future for Eldia or humanity. It’s not that simple. Not really.

Love exists beyond the walls, where people are just people and not monsters trying to wipe out the island. Eren sees this through Falco more than anyone during his time on the continent. Falco is a kind young boy who’s actions are born from a place of love and care. Eren says that he would be happy if Falco could live a nice, long life. Something he’s also told his most precious friends. But... how would that ever happen if Eren let him die?

I can’t say for sure whether Eren accepted Falco as a casualty in Liberio or if he simply trusted in Reiner to protect Falco from Eren’s transformation. But he understands that Falco is very similar to him in that his actions stem from him wanting to protect someone he loves, just as Eren’s are. And he connects with Falco over this.

The way I see it, this story has gone from “who do you eliminate to ensure a better life for everyone” more to a “what do you eliminate to ensure a better life for everyone.”

A boy who killed grown men without any remorse in order to protect an innocent little girl is most definitely capable of growing up to become a man who destroys an entire world he dehumanizes the same way in order to protect those who are close to him. But the thing is, is that Eren doesn’t see the world the way he saw those traffickers and if his personal growth means anything, then he can’t go down the path of total destruction as a means to an end to save a few loved ones. It wouldn’t be right. It wouldn’t feel right to the themes of the story that have been presented. It wouldn’t feel right in the face of all of Eren’s character development.

If Eren, despite all he’s learned and how much he’s grown, has still resigned himself to believing that the path of destruction is the only way, he will have to be pulled out of this mentality before he can cause such a great deal of harm. Particularly if the message to this story is to have any positive meaning.

His coldness isn’t truly benefiting the island. The hatred that fuels the Yeagerists is a destructive force that is only causing divisiveness and more death. Zeke’s drive to euthanize Eldians, born from his self-hatred simply for being Eldian himself, has caused a great deal of pain and suffering among the Eldians on Paradis. And were his euthanasia plan to happen, it will only cause continued misery of the Eldian race as they all watch each other die off slowly with no hope for a future that they were denied.

Hate is a destructive thing. But love? Trust? Kindness and understanding?

Love is a powerful thing.

If Gabi and Falco are meant to represent the future, then it becomes apparent that love is what will prevail and help to push Eldia, and humanity in general, forward in a positive direction.

Eren’s friends know that he loves them. If Mikasa didn’t still believe this somewhere deep down in her heart, she would have discarded that scarf with complete disdain, rather than folding it with care and placing it somewhere gently. Even if they cannot allow Eren to die because he holds the Founding Titan within him, none of them list this as the reason for going to help him in the battle. They all simply don’t want him to die, and they want to understand why he’s behaving this way.

I strongly feel that Eren will come to realize that the love his friends have for him will prevail no matter how hard he tries to push them away. That relying solely on himself is a dangerous path that will lead to more harm than good. He shouldn’t hold the burden all on his own. It doesn’t matter how much he wants to protect them or whether he feels he can trust them not to die.

If any of Eren’s friends are to die in battle again while believing he hates them, I think he would regret that more than simply allowing them to put themselves in danger fighting alongside him. Believing in his own strength rather than the strength of his friends is bound to fail him eventually.

I’m not sure what’s going to happen next, or in what way Eren will have to come to this realization. But, I don’t know... revisiting this scene in the anime between Kruger and Grisha really moved me. As though it was truly a message for Eren.

Don’t let hatred fuel your actions. Love someone. It doesn’t matter who. Let love fuel your actions and decisions.

It wasn’t Eren’s hatred for the Smiling Titan that drove him to punch its hand that day. It was his desire to save someone who he loves dearly. And in that moment, it saved everyone.

It’s only through love that Eren will be able to save Eldia.

#snk spoilers#snk meta#eren yeager#eren jaeger#mymeta#this snowballed a little more into something bigger than my original intent#it's all still just theories and i'm not solid on anything#but that scene at the end of the episode really moved me and i cried#and i think it's proof that eren's thinking of his friends first#and that his mind can be changed about the world#that destroying it isn't the answer to their problems#and i think that he already knows this#i just want to know i'm not crazy for believing that eren is more than a rage machine looking for revenge#i want his story to mean something positive in the end#otherwise what is the point in anything#his mission is to save his friends#because he loves them#when will isayama let us have his thoughts#and see the softer side of him again#i miss him :(#this meta is a mess i'm sorry#i'm fueled by my emotions and love for eren and cant' coherently go down my line of talking points in a way that makes sense lol

645 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julie Herrada, Letters to the Unabomber: A Case Study and Some Reflections, 28 Archive Issues: J Midwest Archives Conference 1 (2003)

Abstract

When the University of Michigan's Special Collections Library acquired the papers of a high-profile person, the standard procedures involving acquisition of archival collections were found to be lacking. This article traces the events leading up to the acquisition of the Ted Kaczynski Papers: detailing the process of negotiating a deed of gift agreement, resolving privacy issues, processing the collection and making it accessible, dealing with the media and a very curious public, handling the administration's concerns, and responding to outside inquiries about the acquisition, as well as practical and theoretical matters affecting the management of controversial and contemporary archival collections.

In April 1996, Theodore John Kaczynski was arrested and charged with being the infamous Unabomber who, since 1978, had mailed or otherwise planted bombs targeting individuals working in the field of genetic engineering, and the airline, computer, and forestry industries. His bombs killed three people and injured 24. The Unabomber had successfully evaded the authorities for nearly 20 years. His manifesto, "Industrial Society and Its Future," was published in The Washington Post just a few weeks before his arrest.

For several months during that year, I, along with much of the rest of the country, watched in eerie fascination the story of the lone outsider who had eluded the authorities for so long as he carried out his bombing campaign. As I read the media coverage about the evidence piling up against Kaczynski and the uproar over the publication of the manifesto, I decided to ask him to donate his papers to the Labadie Collection' at the University of Michigan Library, little realizing what events this would set in motion.

Kaczynski's 35,000-word essay advocated the destruction of technological society before it destroys humanity and nature. The publication of the Unabomber manifesto and its ideas were greeted with a great deal of interest by the anarchist and left press such as Anarchy, Earth First, Fifth Estate, The Nation, and Z Magazine, as well as mainstream publications such as Time, The New Republic, and The New York Times. Kaczynski immediately became a media draw, with everyone wanting to get on the bandwagon by writing about him. Most mainstream journalists and reporters were eager to make names for themselves by publishing the latest "inside" stories or trying to get exclusive interviews. They sensationalized the stories, eager to boost their sales.

Kaczynski also attracted freelance journalists to the frenzy. Radical publications, how- ever, were more interested in analyzing and critiquing the ideas in the manifesto; many of their readers saw him as a modern-day personification of Ned Ludd, the fictional, nineteenth-century British machine breaker. To them, these were not original ideas: they were the same ones that had been discussed within the radical environmental and deep ecology movements since the 1980s. What came to be called "anti-tech" theory (also known as "green anarchism") is well represented in the Labadie Collection. Be- sides his theories, many radical writers also debated the validity of the Unabomber's tactics. The use of violence to overthrow the ruling system or extinguish enemies of the people has been extensively discussed in the radical press for well over a century, and Kaczynski was strongly criticized by some for using such methods. Many anarchists believe in nonviolence, since a basic premise of anarchism is to do nothing that will harm or impinge on the rights of others to live their lives as they choose. It is coercion they abhor. It is also true, though, that some anarchists have engaged in "propaganda by the deed" and, in efforts to prevent further attacks against the oppressed, have taken their beliefs several steps further. Just as with the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901 by the anarchist Leon Czolgosz, some people were supportive of, or at least sympathetic to, Kaczynski's actions.

Since its inception, the Labadie Collection has had a policy of collecting retrospective as well as contemporary materials that document activists and radical movements throughout the world. In addition to anarchism, the collection's strengths include civil liberties, socialism, communism, American labor history, the Spanish Civil War, sexual freedom, the underground press, youth and student protest, and animal liberation. One of my tasks as curator is to continue documenting contemporary social protest such as the radical environmental, global justice, and peace movements. Like Agnes Inglis, the library's first curator (1924-1952), and Edward Weber, the second curator (1960-2000), I do this by keeping up with current social issues in the radical press and writing to activists and authors, asking them to donate their materials. Collecting materials not only about activism but by activists is one of the hallmarks of the Labadie.

The Labadie Collection, now part of the University of Michigan's Special Collections Library, is recognized today as one of the world's most comprehensive collections of materials documenting the history of anarchism and other radical movements. It is a valuable repository of materials used by a wide range of people, from noted scholars who travel there to do research to graduate and undergraduate students at the university and nearby colleges who use its holdings of current and noncurrent periodicals to study radical movements of the present and past. It is part of my job and my passion to ensure that that tradition continues.

Because of my own links with political activists and protest movements, I have been uniquely positioned to acquire new collections. My position in an academic library in some cases grants me a certain amount of carte blanche, while in other circles I am immediately suspect. Occasionally, I have-sometimes boldly, sometimes timidly- pursued the papers of some contentious and notorious, elusive and difficult characters, even people I would not want to meet in person, but that is the nature of collection development. Mostly, the donors I work with care deeply about the world and its people and that alone usually gives me an immediate rapport with them.

The Unabomber manifesto, in addition to diaries confiscated from Kaczynski's Montana cabin, were the type of writings acquired by the Labadie Collection from past radicals. There are no known writings of Czolgosz, but if there were, they would certainly belong in our collection. Letters of Russian anarchist Alexander Berkman, who attempted to assassinate industrialist Henry Clay Frick in 1894 during the Homestead strike in Pittsburgh when Frick ordered his men to shoot striking steelworkers, are in the Labadie Collection. Berkman served 14 years in prison for that crime and, in 1919, during the Red Scare, was deported with Emma Goldman and many others. I do not wish to compare Kaczynski ideologically with either Berkman or Czolgosz: the times and methods are different, as were their targets. I mention them only since they all killed or attempted to kill those they believed were guilty of perpetrating heinous acts upon the exploited of the world.

Kaczynski's brother, David, upon reading the published manifesto in The Washing- ton Post, recognized the writing style and the ideas outlined in it as being very similar in nature to Ted's. The FBI lost no time in investigating Kaczynski and arrested him at his Montana cabin without incident. Subsequently, the manifesto has been published on the Internet, as well as in print, and translated into many languages, including Spanish, French, Italian, German, Greek, Turkish, Dutch, Japanese, Russian, Portuguese, and Czech.

In February 1997, nearly a year after he was arrested, I wrote Kaczynski's attorney, Judy Clarke. It is always a little tricky writing to potential donors. Without knowing exactly what existed and what was available, I asked for everything, including manuscripts, journals, correspondence, photographs, and legal papers. Four months passed and one day I was surprised by a phone call from Clarke, stating, "Mr. Kaczynski is very interested." Clarke had shown a copy of my letter to Kaczynski. He said he would like more information about our library. It was apparent that, even though he earned his Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of Michigan (and won the Sumner-Myers Award in 1967 for outstanding graduate thesis), he had never heard of the Labadie Collection, which is not unusual, especially for someone not studying in the social sciences.

If Kaczynski had not been arrested on suspicion of murder or had not been a notorious figure, I would still have been interested in acquiring his writings, which criticized technology and industrialization, and advocated nature and a return to a more primitive lifestyle, in essence, the kind of writings that oppose the status quo. This is documentation I interpret as being "socially relevant," to borrow Danielle Laberge's expression. 2 What I did not know at first was that Kaczynski had a fairly large following. For example, despite the antitechnology theme, there were many Web sites, such as Unapac (the Unabomber's political action committee) and electronic discussion groups such as <alt.fan.Unabomber> devoted to him. There were also a number of fans writing letters to him. The fact that we must be able to hypothesize about the needs of future researchers is a well-established part of the appraisal process. In so doing, we have the opportunity to unlock secrets. We can heed the call to document the ways in which people are formed in our society as well as the ways those people have shaped our values as a society.

I wrote a second letter to Judy Clarke, including in it the information she requested. Before long, I received my first letter from Ted Kaczynski. With his name and prison number from the so-called "SuperMax" Federal Penitentiary in Florence, Colorado, neatly printed in the upper left corner of the envelope, it arrived in our department from the library's mailroom with a frank question from the person who delivered it: "Is this for real?" A large manila envelope stuffed with correspondence accompanied the letter. It was six pages long and also neatly printed. The correspondence consisted of letters to Kaczynski since his arrest; they were mostly from people he did not know. We did not yet have a formal deed of gift agreement, or even an informal one. His letter explained that he was not allowed to keep more than 20 letters in his cell and, rather than risk having them confiscated and destroyed, he sent them to me for safekeeping until there was a formal arrangement. He acknowledged the possibility that I would not want to keep this kind of material, but was offering me the option before the prison authorities made the decision for me. This was my introduction to Ted Kaczynski. I found his first letter to be candid, explanatory, direct, and unambiguous. This set the tone for the rest of our communication. Kaczynski did not ask any personal questions about me and kept his communication strictly confined to the business at hand, which was to reach a formal agreement as soon as possible regarding the disposition of his papers.

This would prove much more difficult than I anticipated. As our communication progressed, I realized he was extremely concerned with the potential misuse of the collection and wished to place what I considered unreasonable demands on its accessibility, such as restricting it to "serious scholars only." He was particularly concerned with keeping journalists from using it.

We have a standard Deed of Gift form that every donor signs. For most donations it includes all necessary information. This form was far from adequate for negotiating Kaczynski's gift. When he asked us to draw up a deed of gift that placed restrictions on some of his materials, I explained to him that we would not discriminate among users: it was our policy to allow everyone equal access to the collection. He reluctantly agreed. The problem then was the amount of time his restrictions would remain, "the year 2020 or his death, whichever comes later," that would have placed a minimum closure of 22 years on the collection. The only materials he wanted to make available immediately, without closure or redaction, were letters to him that were either anonymous or from the media. These misgivings about the media were at the basis of his desire to keep most of the collection closed. Since his notoriety began, he developed such a disdain for anyone connected to the media and others he perceived as trying to exploit him that he either ignored their letters or answered them with sarcasm; sometimes he was even hostile. In his replies to almost everyone else, he was friendly, congenial, witty, and at times even charming.

Although the Special Collections Library does not have an official policy on length of closure, like most institutions, we discourage any restrictions but are willing to negotiate depending on the circumstances. Kaczynski certainly tested our boundaries. With- out knowing exactly what he was trying to conceal from the public, it was difficult to understand his reasoning. As one who does not trust much in the mainstream news, I sympathized with his sense of being misrepresented by the media, yet I could not in good conscience agree to close the collection for such a long period without understanding why.

Without a formal deed of gift, I was reluctant to open any of the materials he sent, apart from the letters he wrote directly to me. On the other hand, I did not want to risk losing the materials completely to the prison authorities, so I quietly stored them, unopened, in the boxes in which they arrived and continued with the negotiations. I even asked the mailroom workers not to mention to anyone that I was receiving mail from Kaczynski.

When Kaczynski asked that we seal parts of the collection for 20 years after his death, I immediately rejected the request, citing SANs Code of Ethics and our own policy. I gently urged him to reconsider. He then outlined a series of options from which we could choose, creating a classification system based on levels of accessibility. He seemed extremely worried about privacy issues, not so much his own, because by then he was accustomed to intense media exposure, but that of the correspondents who wrote to him. Although he referred to some of the people writing to him as "kooks" and "lonely women," he was still concerned about their privacy.

A further consideration of ours was that the media would find out about the donation before we were prepared to announce it. The university administration was already very nervous about the collection, since some of the Unabomber's victims still lived in the Ann Arbor area. The administration did not want to appear insensitive, nor did they want to open themselves up to increased negative publicity. (There was a high-profile negligence case against the university going on simultaneously.) For the first time in my career, I was at the mercy of the university's general counsel and the provost to negotiate for a new donation. I had spoken to my department head before soliciting materials from Kaczynski; she was very supportive, remaining so throughout the process. But from her superiors I felt some resentment that I had taken it upon myself to seek this donation. They told me that, since Kaczynski's attorney was involved, our attorneys should also be involved. My heart sank. I knew then this was not going to be easy. Until then, I had been communicating well with Kaczynski. We both had our ideas about how the collection should be handled, and we were openly discussing the issues, working to achieve compromises. I know he appreciated my honesty and, by conveying to him the ethical standards by which I was motivated, I was earning his trust. I was, however, disturbed by some of the stories I was hearing about him in the media and I was doing my best to stay detached. I tried to see his perspective as a prisoner with few resources at hand and almost no control over the negotiations for the placement of his papers, not to mention his legal affairs, which included possibly facing the death penalty, certainly a life sentence at the very least. I was determined to treat him with the same respect and consideration I would give to any donor. When the administration got involved, I began to realize the process could break down at any time and that would be the end of it. The power I had was wrested from me, and all my hard work was in jeopardy.

The university attorneys requested copies of all my correspondence with Kaczynski. This was another privacy issue altogether. As in most institutions, our donor correspondence is confidential. I had a choice in the matter: I could have refused. Because I was technically acting as an agent of the university when I wrote those letters, the result of such a refusal may have halted negotiations, or at least stalled them indefinitely. I also did not want to make trouble for my supervisor, who was still very much on my side. In addition, having known from the beginning that my letters were read by prison authorities and could potentially be reviewed by university administration as well, I always kept my correspondence with Kaczynski on a strictly business level. My priority was the swift execution of the deed of gift, rather than the protection of my own privacy, so I handed the letters over to the general counsel.

After a series of letters and drafts of deed of gift agreements, an official one was finally signed on July 10, 1999. Although we had decided not to make a formal announcement about the donation, I knew the story would break soon, so I accessioned the collection and immediately began the processing.

At first I thought Kaczynski's privacy concerns about the letters peculiar, but once I had a chance to read them, I was instantly struck by their personal nature. Coupled with the media's attraction to the story, I sensed a dangerous mixture. Hundreds of people from all over the world were writing to the Unabomber following his arrest. The letters covered a wide range of topics, from mathematics to the environment, philosophy to physical or mental illness, depression, and family and job issues. Many wrote as if they were old friends, discussing their personal problems. Each one found some level at which to connect with this man, whom they only knew from sensationalized reports on television or in the newspaper. Some knew of him through the radical press. It was astonishing to me to see the variety of people he touched: housewives, academics, teen- agers, grandmothers, secretaries, anarchists, journalists, scientists, survivalists, writers, artists, mental health professionals, college students, teachers, and environmental activists, in addition to many women who were interested in initiating romantic involvement. Even though correspondence between inmates was not allowed, other prisoners wrote to him, delivering mail through underground prison channels.

As I read through the letters, I was struck with various emotions: sadness, compassion, and pity, and I began to see what Kaczynski saw in these letters. Waves of despondency crept over me for weeks. I struggled with the sense that these letters represented but a microcosm of the people in our society. They wrote on perfumed paper, colored paper, decoupage paper, anonymous postcards, business letterhead, and frayed-at-the-edges notebook pages. Some were very well educated, others barely literate. They sent photographs of themselves, their gardens, and breathtaking scenery. There were many bright and normal people, as well as some seemingly unstable ones, who were merely curious about the intellect and personality of the man known as the Unabomber. A few people sent complex mathematical equations; some simply wanted an autograph. Many offered prayers and salvation. Others expressed their love of nature, their fear of technology, and their alienation. Several people wanted to know what it was like for him in prison, or how he had lived on the outside. Some of the letters were genuinely fan letters. In this age of constant discussion and debate about how to manage electronic records, this collection is unique in that it is all on paper; in fact, some people writing to the Unabomber apologize to him for typing rather than handwriting their letters based on their assumption that, because he is critical of technology, he disapproves of typed letters. Others printed articles from the Web and mailed them to him, seemingly un- aware of the inherent irony. That there was such a mix of people and ideas did not change the fact that probably none of the people ever imagined their letters would end up in the archives of a public institution. This is what I was grappling with. I even lost sleep over it. Although I had no idea what I would end up with when I asked for Kaczynski's papers, I was now in the difficult position of being responsible for people's privacy, at the same time making a professional pledge not only to care for these materials but to make them available to the public.

My gut reaction was to close this collection for a long time. I had never dealt with a collection so varied, so personal, and so contemporary. I was genuinely worried about the letter writers. I knew that their messages were being read and possibly copied by the prison authorities, and one could assume they also knew this. What they did not know was that I was reading their letters and intending to make sure that many others read them as well. Suddenly, I felt worse than a voyeur. Of course, it was not the first time in my career that I felt I was intruding on something very private, but this time the feeling was much stronger than ever before, partly because these letters had been written within the past two years. The writers were still around, some of them still corresponding with Kaczynski. I felt the weight of the world was on my shoulders. I felt like giving all the letters back. I certainly did not feel entitled to them.

One of Kaczynski's early suggestions was to black out the names and other identifying features of the authors. Initially, this seemed like a bad idea to me, mainly because of the work involved. We discussed other options such as closing the collection but, given the youth of many of the writers, a reasonable time of closure would not have protected their privacy for very long. Fifty years might do it, but anything less was risky. This would have made no sense and would have violated our own policy of non-closure. There are no hard and fast rules governing the privacy of third parties in archival collections, only guidelines and professional ethics. Typically, archivists prefer not to see restrictions on use because restrictions can inhibit research. The contents of the letters to Kaczynski were of potential interest to researchers, but the names of the writers were irrelevant except to the press, and the press was my major concern. Kaczynski and I discussed these issues at length. I consulted with trusted colleagues. I researched the policies of other institutions. I interpreted the SAA's Code of Ethics.

The letters to the Unabomber were a surprise to me but are a useful element in understanding our society and, after several weeks of research and meetings and discussion and soul searching, I was finally convinced that the content of the letters was very much worth keeping intact. These letters certainly meet Laberge's definition of "socially relevant"; however, revealing the names of the writers served no ethical research purpose and, indeed, in many cases would be an invasion of privacy and could seriously harm the author. One could guess that even if some of them signed their letters, they would want their names kept out of the public eye.

The decision to redact the names from the letters to protect the privacy of the third parties had another result. Third parties retain their copyright (currently, life plus 70 years). Making the names of the writers inaccessible means that no user can seek permission from a writer to quote from or publish any of the letters. One exception to this is letters written by people already in the public eye: their names are not redacted since they are not allowed the same rights to privacy as private individuals. These public figures have been, for the most part, media personalities who have written to Kaczynski in the hopes of procuring an exclusive interview.

Eventually, the media found out about the donation. They began calling. For the first time in my life, I felt I was being forced into the public spotlight and I did not like it. I was able to fend most of them off at first, giving them very little information and telling them that the processing of the collection was expected to take six months and that until that time I could not tell them anything about the papers. That worked with most of them, but some reporters were so aggressive that I began to find Kaczynski's contempt for the media justifiable.

Given the expectations of the donor and the media and the sense that this would be a popular collection, I knew it would require immediate access. The processing took a full six months. I hired an excellent archival student to do most of the work of redacting the initial four and a half linear feet of correspondence. By this time, I had read many of the letters and was certain about what needed to be done. We were preserving the originals but wanted to conceal names, addresses, phone numbers, and sometimes place names for added protection. Envelopes and photographs of people were not copied but were stored with the original letters. The process was very time-consuming; however, it was the only precise method we found. Each letter had to be read thoroughly to catch any possible reference that might lead to an individual. I certainly do not recommend this method for every sensitive collection. This is an issue that must be carefully thought through and discussed with responsible parties. Relying on your instincts and training as a professional is also an essential tool.

Early in our negotiations in an effort to assemble a more complete record, I asked Kaczynski to send me carbon copies of his own correspondence. He complied. He can read and write German, Russian, and Spanish, so he has international correspondents as well (although he is now prohibited from corresponding in Russian since the prison authorities cannot properly screen Russian-language materials). All his incoming and outgoing letters are read and possibly photocopied by the prison authorities. There are now over seven hundred different correspondents.

We considered creating a special permission form in addition to our regular Application for the Use of Manuscript Material. My experience with the media reinforced my decision to black out the names in the letters. It also convinced me that a special form would not prevent cunning reporters from doing what we were trying to prevent, since permission forms are not legally binding. In addition, there was no need for such a form if we were going to conceal the names. The way the media descended like vultures upon me and anyone else who was in any way associated with Kaczynski was nothing less than barbaric. Once the collection was processed, I could not keep the media out. One local reporter, after an hour's interview, wrote a fair, honest article, even allowing me to review it prior to publication. Everyone else was not only unprofessional but simply looking for a way to disgrace me. An on-line radio talk show host even asked if I considered Kaczynski "attractive." I had the choice not to talk to reporters but I thought this might be worse for me and for the university. Being direct and firm seemed to be my best defense against the onslaught.

Even though several years have passed since the story of the collection became public, every six months or so I get call from a magazine or newspaper reporter wanting to do another article on the papers. The story has been covered in many newspapers across the world, including one in Russia, for which I was interviewed by E-mail. Sometimes,

in order to fend off unwanted attention, I remind them that the story has already been covered many times. A few years ago there was a brief flurry of negative publicity about this collection when a conservative radio talk-show host urged his listeners to call the university library and complain about the fact that we were "glorifying" Kaczynski by placing his letters on display (we had not done this). The library's public relations unit requested that I not speak to anyone in the media about this issue and that I refer all calls to them or to the university's News and Information Office. I had a mixed reaction to this, feeling somewhat censored, but overall I admit I was relieved to let someone else handle the calls.

In 1998, Kaczynski pled guilty to murder charges in exchange for a life sentence. He then began an appeals process, asserting that he was forced to plead guilty because his lawyers, in an attempt to avoid the death penalty, insisted on presenting evidence that would have portrayed him as mentally ill. He also appealed on the grounds that the court would not allow him to act as his own lawyer. He represented himself in his brief to the Supreme Court. On March 18, 2002, his final appeal was denied. Since he has exhausted all his legal channels, he is now sending me the court documents related to his case. The collection now spans nearly 20 linear feet and is still growing.

Part of what is interesting and relevant about Kaczynski is that his views on technology are antithetical to an archivist's work setting, especially my own, given the University of Michigan's reputation for being at the forefront of technological innovation. As Hans Booms believes, archivists cannot "separate [ourselves] from the socio-historical conditions of our existence." 3 The technological movement is part of our social context, making it difficult though not impossible to be critical of it. Part of what attracted me to the archival profession in the late 1980s was the scarcity of computers within it. The joke is on me. I still love what I do, despite the fact that technology increasingly dominates much of my archival work. I have resigned myself to the modem methodology and have accepted the role of technology in it.

Kaczynski is in the tradition of those Americans who have been outspoken in their rejection of technology and modernity in their lives, from Thoreau to Scott Nearing. Kaczynski is unique, however, for the methods he employed to make his views known. Also, it is slightly ironic that just as Jo Labadie donated his radical papers to the University of Michigan in 1911 to balance its conservative philosophy so, in 1999, Ted Kaczynski's papers ended up there despite the university's overwhelming commitment to technology.

The fact that I have experience with contemporary and controversial donors puts me in a smaller category of archivists. But if we are to have more complete records documenting social history, this category needs to grow. I would very much like to share this responsibility. Historical societies and other institutions documenting local history should be collecting materials relevant to their communities, especially if they are controversial. These materials may otherwise be destroyed or discarded out of shame, embarrassment, fear, or misunderstanding. If we, as keepers of history, collect and protect only what is appealing, socially acceptable, or politically correct, we are hardly doing our jobs. In his article "Mind Over Matter," Terry Cook reminds us that:

... In any appraisal model, it is thus important to remember the people who slip through the cracks of society. In western countries, for example, the democratic consensus is often a white, male, capitalist one, and marginalized groups not forming part of that consensus or empowered by it are reflected poorly (if at all) in the programmes of public institutions. The voice of such marginalized groups may only be heard (and thus documented)-aside from chance survival of scattered private papers-through their interaction with such institutions and hence the archivist must listen carefully to make sure these voices are heard.4

Because I am now publicly connected to the Unabomber, people dealing with similar collections call on me. Two years ago, I received a phone call from a representative regarding the placement of Timothy McVeigh's fan mail and last year I was consulted about the placement of papers and artifacts belonging to the Branch Davidians. In both cases, I spoke with an intermediary. I took heart when each of them conveyed the deep concerns of the donors that the materials be protected and made available. McVeigh even had legal documents drawn up prior to his execution that detailed his wishes for preservation of and access to his letters. I did not have to tell these people how important the collections are: they already knew.

It is also important to think about which institution can best care for the materials. Large and well-funded archives have prestige and can appeal to prospective donors, but smaller, local archives, museums, and historical societies are often more accessible and geographically more desirable. I am a strong proponent of collections being properly geographically placed, close to the point of their creation and accessible to the most users. I could argue that Kaczynski has ties to the University of Michigan and, there- fore, his papers belong there, but he also has ties to Berkeley, Chicago, and Montana. And nothing in the papers is connected to the time he spent in Ann Arbor, Berkeley, or Chicago. Montana seems to be the closest geographic connection. Being properly cared for and cared about, however, is fundamental. The Branch Davidians's collection most assuredly belongs in Texas; it stands to reason that the McVeigh letters belong in Oklahoma City, but the people of Oklahoma City might disagree with that.

I cannot stress enough the value in collecting contemporary materials. Booms says the appraisal process should include a study of the major events of the times in which the collections were created.5 That is easy if we are already living in those times. We have ready access to most current debates and controversies regardless of which side we personally take. We might be appalled and bewildered by some of the events of our era, but we have the resources, the social values, the context, and the perspective to thoroughly document them. Society's reactions to events are just as important as the events themselves. I think about a letter written by Agnes Inglis in 1928, when she was feeling overwhelmed by her work in the Labadie Collection:

... It takes time and constant interest and effort. I realize I have to stay on the job. But sometimes I find it rather hard to do, for after all, that has all been lived. It's wonderful historically but lacks one's present day heart beats. I have to have a life besides.6

In his article, "Keeping Archives as a Social and Political Activity," Booms's focus is on appraisal of older documents but, if he had discussed contemporary documents, his argument surely would have followed that archivists are best able to chronicle those collections in which their own social values are summoned.7 Recently, I have been collecting materials related to the current antiwar movement. These materials are mainly in the form of flyers, buttons, and posters. That the largest antiwar movement in history has been organized across the world to include radicals, liberals, and mainstreamers is truly a historical occurrence. It comforts me to see and touch it, the tangible evidence of a mass movement of social protest, to know that it is being saved, and that, generations from now, people will acknowledge the work we have done and study the materials we had the foresight to preserve from our own time. The better we document our society's transformations, the better we will be able to learn from those transformations.

Another good reason to collect contemporary documents is that archivists are often stuck with collections that someone else first had the opportunity to rifle through. The best time to collect is not years or decades later, after who knows how many hands have touched them, but as soon after their creation as is feasible. Regardless of what those materials consist of, we all know this task of sorting and weeding is best left up to the archivist during the appraisal process.

Frank Boles correctly asserts that we must educate the public about the importance of collecting controversial materials. 8 This can be done in many ways, the least of which can be to educate them in general about archives: what they are and how they can benefit society. One of the simplest ways is to utilize the resources that are the most accessible. It is true, as Boles states, that "Reporters understand the archivist's view- point regarding the acquisition of controversial material much better than the general public." 9 Reporters also understand (and are often motivated by) the general public's attraction to scandal and tabloid news. The public will not be educated about the value of archives overnight. It is a gradual process; the more archival collections make it into the news, the more people will become accustomed to the ideals we have been putting forth.

It is possible that some patrons or donors or members of the general public may criticize you and your institution for obtaining certain collections. Some prospective donors may even change their minds about giving their materials to you. This again is where education and diplomacy become important. You may not be able to please everyone with your explanations, but placing your mission statement ahead of their attempts to dictate your collection development policy will be liberating in more ways than one. And, like it or not, this is how we get attention in our profession. A little controversy about our collections is better than whitewashing social history.

We are fortunate to be in a profession for which we have a passion and a calling. It may not be a lucrative one, especially these days when most of our cultural and educational institutions are under serious financial strain, but it is a profession that we do not have to worry about being moved to a developing country in order for a corporation to reap more profits. We will always have the responsibility to practice good ethics and to collect, preserve, and make accessible the papers and records and artifacts of underrepresented communities, unpopular individuals or groups, and marginalized movements. The FBI should not be trusted as the only organization to collect these materials. Their motives are singular, making their methods much different from our own. We are a richer society for the things from the past we have managed to save, but we have a long way to go in overcoming our prejudices, our biases, our snobbery, and our fears.

Footnotes

The Labadie Collection is named for Joseph Antoine Labadie, who was born in 1850, in the back- woods of Paw Paw, Michigan. His father, a wandering free spirit, taught his eldest son the ways of the frontier and introduced him to the life and language of the native Pottawatami tribes living nearby. With almost no formal education, Jo was trilingual, speaking the native French and English of his family and learning Pottawatami from his neighbors. In his teens, he was trained in the printing trade and went on the road as a tramp printer, working in print shops throughout Indiana, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Michigan, joining typographical unions everywhere he went. This experience gave Jo a class consciousness that would stay with him the rest of his life. He became a labor union organizer and an anarchist. By the turn of the century, he had amassed a large collection of correspondence, essays, poetry, newspapers, pamphlets, posters, photographs, broadsides, leaflets, badges, and other materials, and wanted to make sure it was preserved and made available for research. In 1911, despite several offers from the University of Wisconsin, he chose to donate it to the University of Michigan because he wanted it to remain close to his home but also because he felt his collection would give the conservative Michigan institution some much needed balance.

Danielle Laberge, "Information, Knowledge, and Rights: The Preservation of Archives as a Political and Social Issue," Archivaria25 (1987-1988).

Hans Booms, "Society and the Formation of a Documentary Heritage: Issues in the Appraisal of Archival Sources," Archivaria24 (1987): 74.

Terry Cook, "Mind Over Matter: Towards a New Theory of Archival Appraisal," The Archival Imagination: Essays in Honour of Hugh A. Taylor, ed. Barbara L. Craig (Ottawa: Association of Canadian Archivists, 1992).

Hans Booms, "Oberlieferungsbildung: Keeping Archives as a Social and PoliticalActivity," Archivaria 33 (1991-1992): 31.

Agnes Inglis, letter to Jo Labadie, 6 September 1928, Joseph Labadie Papers, Labadie Collection.

Booms, "Uberlieferungsbildung."

Frank Boles, "Just a Bunch of Bigots: A Case Study in the Acquisition of Controversial Material," Archival Issues 19:1 (1994).

Boles, 60.

#case study#political violence#unabomber#psyche#ted kaczynski#correspondence#technology#law#deviants#anti-technology#rebels

2 notes

·

View notes