#and do more of an office/clerical job than a manual labor job

Text

just want to play persona all day. but I have """responsibilities""" 🙄🙄🙄🙄

#not really LOL#i have the TA course i should finish#admitted to bf finally that im not into the TA job anymore but ill still finish the course cause its still good info if we ever have kids!!!#i wanna be able to help my own kids with homework and i have no basis for that cause nobody ever helped me LOL#anyways i wanna take the admin asst course but its another $1100 i do not have rn#soooo. just gotta wait it out a bit#finish the TA course then ask for money lol#but if i finish admin asst what im hoping is i can reapply to my old job as a fresh start in a brand new position once they've expanded#and do more of an office/clerical job than a manual labor job

0 notes

Text

just some thoughts under the cut.

this is a mixed bag of a post.

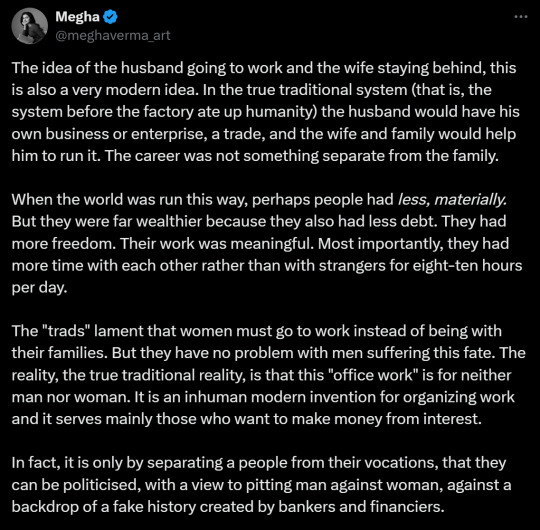

it's true that the idea of a husband going to work and the wife just staying home is definitely a very very modern idea.

but the rest of the first paragraph is a bit questionable. the system before "the factory ate up humanity"? not sure what's meant by this. before the industrial revolution? before capitalism? what is the system that preceded these? you mean agrarian feudalism? where most people (like 90%, depending on the region) were farmers?

yeah most men, throughout history, did NOT "have his own business or enterprise". as i said, most men would have been peasant farmers. maybe a tiny percentage were lucky enough to be yeomen/freeholders. but yeah, men and women, for most of this period, would have both been doing lots of work around the farm. in urban areas, maybe the women would work as laundry workers, chamber maids, prostitutes, weavers, brewers, midwives, etc.

yeah if a woman was lucky enough to be married to a man who did operate his own enterprise she most definitely would have helped him with it but this wasn't a common situation. it'd be the premodern equivalent of being upper class.

in fact, this is one of the things that makes america so special because it actually broke this mold. from america's founding onward we have had a high rate of independent (family run) businesses, yeomen farmers, homesteaders, land ownership, etc. so yeah what she's describing here only would have really been relatively common in america (post-industrial revolution).

also, i don't know how true it is that people has less debt. debt has been an issue since time immemorial. but i also don't believe less debt necessarily means wealthier? in fact, in reality it seems like the opposite. many of the richest people in the world have lots of debt. most of the richest countries also have lots of debt. debt almost seems like a prerequisite for debt.

had more freedom? in what sense?

their work was meaningful? according to what metric? and compared to what? i live in a town that has a pretty strong manufacturing base and i know the factory works are very proud of and find a lot of meaning in their work.

they had more time with each other? perhaps.

"The "trads" lament that women must go to work instead of being with their families. But they have no problem with men suffering this fate. The reality, the true traditional reality, is that this "office work" is for neither man nor woman. It is an inhuman modern invention for organizing work and it serves mainly those who want to make money from interest."

i mean, yeah, obvious i support people in general, both men and women, getting more time to spend with their families. but like in "traditional" societies everyone is still working. even the kids for the most part. it's not like everyone is just chilling together all day. and even in premodern times there were still office jobs and clerical/administrative roles and bureaucracy and all that. that stuff isn't any more inhuman or modern than pretty much any other job short of hunting and gathering. like, i've seen people say agriculture is inhuman/unnatural. i personally think that's silly but you do you.

again, i'm in favor of reducing the amount of work people do and increasing time spent with family and for recreation and stuff. but this just seems no better than the idiotic prattle of other trads.

speaking as someone who has spent my life doing backbreaking manual labor and whose body is already breaking down as i approach the age of 30 i'd love having an office job. in fact in premodern times having an "office job" would have been "making it". the way everyone wants their kids to become doctors and lawyers and computer programmers, premodern folks wanted their kids to become priests and scribes and accountants and so on. there's a reason why people are leaving their "traditional economy"-based countries and rushing to becoming office workers in modern economies.

not saying office jobs are extremely fulfilling or anything. but digging ditches or pulling weeds ain't that fulfilling either. most jobs in general are just shit. lmao. if they were fun times you wouldn't have to be paid to do them.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

will attempt to articulate this more coherently later but i think a lot about the cluster of executive dysfunction problems called adhd & the (imo partially correct but also reductive) refrain that "adhd is only a pathology under capitalism, i.e., these traits are labeled deviant/distressful/dysfunctional because they render those who posses them economically unproductive & that is unacceptable in a society that reveres Productivity (which it regards as both the means of perpetual wealth accumulation & a moral imperative in & of itself) above all else." some points that have been kicking around in my head:

- the statement that "some people are too poor to get jobs" initially applied to requirements like a permanent address, "professional" interview attire, access to transportation, & legal ID; now, it often extends to a working laptop, an internet connection, & a cell phone, because so much of it is On The Computer

- as that one article noted, increasing digitization has drastically reduced the decision-making load, as well as the manual/tactile aspect, of even "menial" clerical jobs; there's less cognitive engagement, there's less sensory & social enrichment (you're not delivering memos in person, you're typing an email & CC'ing the office); there's less *movement*, so you're more sedentary (you're not walking to the printer, you're entering numbers into a spreadsheet on the cloud). it's alienating & *also* demands MUCH more sustained, active *attention* than this sort of work ever has

- the secondary "circadian rhythm disorders" often diagnosed w/ adhd don't actually affect sleep quality or cause insomnia unless the person is required to get up or go to bed at "conventional" times that correspond to *office* job hours, i.e., the 9-5 workday plus commute; the patterns hew pretty close to bimodal/biphasic sleep, which was much more common--predominant, even--before the advent of artificial lighting around the industrial era

- just speaking for myself--a person diagnosed in the top 99th percentile, adhd mixed type--i still struggled with some aspects of executive dysfunction, but improved enormously when i lived on a sailing ship, slept in 8-hour shifts, & worked with my hands

- like i'm not advocating a Back 2 The Garden approach or anything & i'm certainly no luddite, but it's not just alienation in the "relation of the worker to the products of their labor" sense; even with editing, there's a materiality that's lost & WAY more attention required when everything is digital. it's been demonstrated over & over again that copy editors & proofreaders consistently make more mistakes when editing in word processing programs than they do when editing manuscripts by hand. it's not just "manual" labor like hauling ropes on a ship & it's not just "production." like fully automated luxury communism would create an adhd epidemic, y'know--it's the automation of everything, not just working conditions, as much as the overarching economic system

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blue Collar Vs. White Collar Workers — Which one you wearing? | Jobsmama India

Blue Collar Vs. White Collar Workers

How often do we hear, an HR tagging a job role as a blue-collar or white-collar? Probably, many times if we share a common table with HR personnel during lunchtime. Ever wondered, what’s the difference between them? Let’s explore more in this article.

The job roles can be classified under specific collar types like blue, black, white, pink, etc. There are even other collar jobs like black, pink, etc., where every collar has a symbolic meaning. For example, the pink collar is referred to as a profession that is specific to women, like nurses. Similarly, the black collar is referred to as masculine professions like oil drilling, mining, etc.

To understand the difference between blue-collar and white collared job roles, let us understand their terminology first.

Blue collar –

The name ‘blue collar’ comes from the early 20th century when workers used to wear blue uniforms or blue denim or resistant fabrics. They preferred using this color or fabric to avoid washing daily. Their job roles involved tasks that may catch dirt at work, and they could not afford to wash them on the working days. It is the uniform that they can comfortably wear for a couple of days and wash them on their weekly holiday.

White collar –

White collar workers are those working in the office and the jobs are more of an executive level. The writer Upton Sinclair coined this word in his writing. The white-collar jobs are often referred to as jobs of administration, financial, bank, etc. whose task is to work within the closed walls of the office premises.

Difference between white collar and blue collar –

Place of work — The foremost difference is the place of work where these two categories of workers perform. The white-collar workers sit inside the closed rooms of an office and work. Their job is mostly clerical type. Whereas, the blue-collar work in non-office settings as their job involves on-site like construction, production, road, etc.

Abilities — The blue-collar workers often work on their desks sitting in one place. Their job role involves their mental ability and they don’t have to be physically strong except to maintain good health. The white-collar jobs involve a lot of physical activity and therefore, the workers should be capable of performing manual jobs.

Education — Where white-collar jobs require a specific degree or professional qualification, blue-collar jobs do not ask for higher degrees. The blue-collar jobs look for the physical proficiency of the workers.

Pay — The white-collar workers are paid higher than blue-collared. But we cannot conclude on it as there are variations due to experience and proficiency.

Legal regulations — The white collar workers are mostly the employers working for a company and therefore, their rights are governed by the Companies Act, 2013. The blue collar workers often fall under the labor category and therefore their rights are defined by the Labor Law.

With the world going digital, white-collar jobs have evolved over many years and today they are the most sophisticated jobs. IT, ITES, telecom, hospitality, designing, etc. are a few examples of job roles that can be considered under white collar jobs. Jobsmama.in hosts the best IT jobs, Software Engineer jobs, Senior Software Engineer jobs, Senior PHP Developer Jobs, and other IT Jobs in Bangalore, Hyderabad, New Delhi, Noida, etc. You can post your resume on our website to get access to these jobs and apply them.

#jobsmamaindia#jobsbangalore#jobs in hyderabad#jobsinnoida#jobsindelhi#bluecollarjobs#whitecollarjobs

1 note

·

View note

Photo

VOX

The president is the billionaire head of a global business empire, and his mostly millionaire Cabinet may be the richest in American history. His opponent in the 2016 election was a millionaire. Most Supreme Court Justices are millionaires. Most members of Congress are millionaires (and probably have been for several years).

On the other end of the economic spectrum, most working people are employed in manual labor, service industry, and clerical jobs. Those Americans, however, almost never get a seat at the table in our political institutions.

Why not? In a country where virtually any citizen is eligible to serve in public office, why are our elected representatives almost all drawn from such an unrepresentative slice of the economy?

It’s probably worse than you think

This year, it might be tempting to think that working-class Americans don’t have it so bad in politics, especially in light of recent candidates like Randy Bryce, the Wisconsin ironworker running for the US House seat Paul Ryan is vacating, or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the former restaurant server whose primary election win over Democratic heavyweight Joe Crowley may go down as the single biggest election upset in 2018.

In reality, however, they are stark exceptions to a longstanding rule in American politics: Working-class people almost never become politicians. Ocasio-Cortez and Bryce make headlines in part because their economic backgrounds are so unusual (for politicians, that is). Their wins are stunning in part because their campaigns upset a sort of natural order in American politics.

The figure above plots recent data on the share of working-class people in the US labor force (the black bar) and in state and national politics. Even in the information age, working-class jobs — defined as manual labor, service industry, and clerical jobs — still make up a little more than half of our economy. But workers make up less than 3 percent of the average state legislature.

The average member of Congress spent less than 2 percent of his or her entire pre-congressional career doing the kinds of jobs most Americans go to every day. No one from the working class has gotten into politics and gone on to become a governor, or a Supreme Court justice, or the president.

And that probably won’t change anytime soon. The left half of the figure below plots data on the share of working-class people in state legislatures (which tend to foreshadow demographic changes in higher offices) and the percentage of members of Congress who were employed in working-class jobs when they first got into politics. As a point of comparison, the right half of the figure plots data on the share of state legislatures and members of Congress who were women. (Of course, these groups overlap — a woman from a working-class job would increase the percentages in both figures.)

The exclusion of working-class people from American political institutions isn’t a recent phenomenon. It isn’t a post-decline-of-labor-unions phenomenon, or a post-Citizens United phenomenon. It’s actually a rare historical constant in American politics — even during the past few decades, when social groups that overlap substantially with the working class, like women, are starting to make strides toward equal representation. Thankfully, the share of women in office has been rising — but it’s only been a certain type of woman, and she wears a white collar.

Government by the rich is government for the rich

This ongoing exclusion of working-class Americans from our political institutions has enormous consequences for public policy. Just as ordinary citizens from different classes tend to have different views about the major economic issues of the day (with workers understandably being more pro-worker and professionals being less so), politicians from different social classes tend to have different views too.

These differences between politicians from different social classes have shown up in everymajor study of the economic backgrounds of politicians. In the first major survey of US House members in 1958, members from the working class were more likely to report holding progressive views on the economic issues of the day and more likely to vote that way on actual bills. The same kinds of social class gaps appear in data on how members of Congress voted from the 1950s to the present. And in data on the kinds of bills they introduced from the 1970s to the present. And in public surveys of the views and opinions of candidates in recent elections.

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#vox#economic inequality#electoral politics#working class#progre#progressive movement#alexandria ocasio-cortez#randy bryce

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is Some Labor Issues at Your Place of Business?

In most industries, the term "labor" refers to people who perform a variety of jobs that involve moving, stacking and moving goods. But in the United States and Canada, where labor laws are more restrictive: arbeidsrecht. The definition of "labor" has become more broad. In other words, the definition of "labor" encompasses a much wider range of occupations and responsibilities than in countries with more liberal labor laws. This is due to the fact that many industries are composed of multiple types of operators and supervisors and therefore require operators and supervisors to work in more complex ways than in countries with more regulated markets.

In addition to the more commonly recognized forms of manual labour, there are two additional forms of labour that are protected by the law. The first is "truck drivers" for hire. This form of labour is highly regulated because it involves a high level of physical risk and danger. Operators must be professionally trained and licensed by the Canadian authorities in order to be allowed to drive trucks for hire. Drivers can be paid an hourly wage or paid by the hour, depending on the laws of the province in which they live. The trucking industry enjoys the most regulated form of non-office employment in the Canadian economy.

Another highly regulated form of non-office employment is "tradesperson" work. A tradesperson is a person who engages in the business of buying and selling products. The activities of a tradesperson can include anything from selling used goods, like furniture, to producing new goods, like electronics equipment. A tradesperson can also engage in activities related to technology, such as creating software or assisting other professionals in the creation of new information technologies. A tradesperson may also be a seller of used goods, like a retailer, and can be considered a skilled worker in the market place.

In addition to highly regulated professions, there are many occupations that fall under the category of "semi-skilled" labour. These occupations include the following: administrative specialists, whose job it is to perform clerical or secretarial work; computer operators and technicians; skilled labors, such as painters, carpenters, and welders; and agricultural workers, including farmers, fishermen: www.juridicaldictionary.com. And lumberjacks. These individuals are generally not paid hourly wages, but instead are paid by the job. Semi-skilled labors are generally paid by the hour. This means that they receive the same amount of pay whether they work one hour or one day. These are some of the questions that may arise, such as: What are the differences between semi-skilled and skilled labors?

What are some examples of what labor issues mean? Some employers choose to hire people who do not have the same education and skills that other employees have. For example, a business that is making appliances may choose to hire a laborer who cannot do the job because he does not have the proper training. As an example, a laborer who has never been trained in plumbing would be a poor choice to work on a carpentry job. The company would need to know what skills the person has and how much experience he or she has in order for him or her to be hired. Another example is if an individual who was born with a physical handicap decides to take a job as a mail carrier, then he or she will be considered a disabled person, and his or her abilities will need to be assessed.

What are some ways in which an individual can resolve what are some labor issues? One way that an individual can resolve what are some labor issues is by organizing. In a society that is run by corporations, everyone needs to get organized, and this includes workers. If you belong to a union, you will be able to make a voice for yourself and your rights.

How do you go about making a voice for yourself? One way to go about making a voice is by joining the local newspaper, as they will be able to help you find out what are some what labor issues are. This is especially true if the local newspaper has a labor section. If the local newspaper does not have a labor section, then you may want to look into forming one of your own.

Now that you understand the answers to what are some labor issues, you may want to do something about them. Do not let them happen, and try to find ways to help alleviate them. It is important to know that your rights are not always protected, but when you do something to improve the conditions of the working conditions, then the law will protect you: testament opstellen. If you are not comfortable doing something to help your working conditions, then you should consult with a lawyer who will be able to give you advice. You should do everything that you can to improve your working conditions.

#arbeidsrecht advocaat#advocaat arbeidsrecht#arbeidsrecht advocatenkantoor#advocaat#beste letselschade advocaat

0 notes

Text

Beyond The Pale

Bohr Euclid Yuferov Orwell Nikola Descartes Maxwell Oswald Rousseau Tchaikovsky Albert Ludwig Ueda Napier Dostoevsky Emmanuel Raphael Sales Tolstoy Asimov Nietzsche Donatello Imhotep Newton Goethe, more concisely known to peers as Beyond The Pale, is a lowly and insignificant worm of a Devil. Beyond has no notable features and is so feebleminded that it's hard to justify calling it sentient. It absolutely isn't under any circumstances the multifaceted criminal genius that masterminded the greatest heist to ever befall the Bank of the Grand Dragon, nossir officer. Look, it can't even talk!

An angel's age ago, a Vatra in the employ of the Bank of the Grand Dragon named Runiphreas Tyran and his subordinate Jai-Fen Lo had been permitted a sliver of the demiurge's Wheel-rending magical might. Drunk with power, they decided that their gifted minds were far too taxed by the menial work that the bank's bookkeeping demanded, and made it their mission to bind several strong Devils to do the job for them. Thus formed the Auraurum, an elite cadre of gilded Gold Devil accountants whose acute mental facilities and tirelessness served well to keep perfect record of the assets flowing into and around the bank. Bound by their agreement, the Devils were perfectly loyal servants to Runiphreas and Jai-Fen, fulfilling every command thoroughly and to the letter. When Runiphreas mused aloud that it would be fortunate if there were to be some kind of clerical error and a measly sum of ten gold pieces were to be misplaced from the vault every few weeks so that the two of them could line their pockets without Mammon ever knowing, the Devils were quick to see it done posthaste.

One week later, Runiphreas and Jai-Fen were put back to work in the clerical hall. Their skins had been tanned to leather to bind the ledgers and the iron of their blood forged into delicate pen nibs that the Auraurum continued to scribe with. The Gold Devils had been spared not by mercy but as a matter of penny-pinching; the binding of even one Gold Devil is not inconsiderable in cost, and Mammon would not let several go to waste. But Mammon is also not forgiving, and so the Gold Devils would not go entirely without punishment. Mammon would get his money's worth out of these Devils by working them until their masks splintered and their flames flickered out into the wind. The realization of their plight came slow to the Gold Devils, who thought they had evaded retribution, but there was little they could do. The magic which had been used to bind them was Mammon's own, lent to the Vatra but now reclaimed, and the Devils had no recourse but to follow commands or break their pacts and their masks alike. The more clever of the bunch did so, choosing suicide over an eternity of servitude. One did not.

Philippus Aureolus was one of the Auraurum and served for decades in the accountancy halls, taking stock and record of every gold piece and exactly who owned and owed what. Every transaction in a hundred years was locked in his mind, the names of investors and guild merchants and crime lords who all stored coin in the vaults a nebulous cloud of information within his mind. This was information, he realized, that very few had such access to. He spent a hundred years working diligently and memorizing the ledgers. In that hundred years his mask tarnished, bright and brilliant gold corroding into rusty green.

No longer suitable for the desk job, Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus the hulking Green Devil was commanded to a job of manual labor, lifting the very same chests of gold and gems that he had once kept record of to and fro among the vaults of the bank. The work was tiresome, and with nothing but time to be alone with his thoughts his resentment for this imprisonment was building. His routes and duties spanned every inch of the fractal fortress Yre, and as the leathery membrane of his draconic wings ripped apart with age and the green scales on his mask tore away to reveal the bloody red wooden mask beneath, he gained a mental map of all of Yre and knew step for step which door held which Preem's treasure.

Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus the brutish Red Devil was assigned to be an enforcer, little more than cannon-fodder to take the thrusting swords of debtors who couldn't pay the Grand Dragon. Though his job remained the same his position often rotated, a new detachment of mercenaries always needing some enslaved Black Flame to shore up their numbers. He was able to see from within exactly the strength of the brigades that Mammon used to defend his rule: the guards within, the sellswords without, everyone whose pockets were filled by Mammon's employment at one point or another had use of a Red Devil to push around.

And after his red face had been beaten black and blue, Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim the pitiful Blue Devil was made to serve as a liaison between the Grand Bank and its debtors and investors. He did the legwork that important people couldn't be bothered with, bringing invoices and demands for tax to the less fortunate or interest and dividends to the successful brokers. While his Red Devil days had taught him who the Grand Bank had in its pocket, these ventures revealed where the assets flowing into the bank were coming from. These were the people who were hoping the bank did well, and a few who held onto foolish dreams that it would somehow go under and their debt would be erased.

And finally, after a thousand years of service, all color and life drained from its mask, Beyond the Pale was made be a messenger and do all the sundry duties that only a Pale Devil can do because there's not much else a Pale Devil is good for. It was not uncommon to hear the claws of one of these little cretins crawling in the walls, out of sight of decent folk but easily accessible to deliver mail and reports to the higher-ups of the bank. It was through this messenger routine that he came to appreciate the inner workings of the non-combatant employees within the bank. Who was in whose pocket, who had secrets they didn't want to get out. People spoke freely around a Pale Devil. It can barely think, it has no ability to understand its surroundings beyond what it needs to in order to serve. And how's it going to spill a secret if it can't even speak?

Beyond is now fueled by two things: Desperation and seething fury. Its time is running out - trapped in its binding by Mammon there's little flame left before it flickers out entirely. It's been an enslaved as a servant for a thousand years and never had the freedom to act as it pleased, and every moment of its life now pours into the desire of for furious vengeance. Every step of the way it has gained the knowledge of the Bank of the Grand Dragon inside and out, and there is no soul on the Wheel better suited to taking down Mammon than itself. But while its mind stays sharp by determination alone, its body is weak and powerless. It has to scratch words into the sand in order to be understood, or write in pictographs on a slate. Beyond needs a miracle coming from an unlikely source if it's going to be able to bring the culmination of its life's effort together for the greatest heist that Throne has ever seen.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cities have stopped providing middle-class work

The great U.S. economic boom after World War II was an urban phenomenon. Tens of millions of Americans flocked to cities to work and forge a future in the nation’s middle class. And for a few decades, living in the big city paid off.

By 1980, four-year college graduates in the most urban quartile of job markets had incomes 40 percent greater, per household, than college graduates in the least urban quartile. And workers without four-year college degrees (“non-college” workers) in the same urban areas had hourly wages 35 percent higher than their rural counterparts.

But those were different times. Since 1980, the U.S. landscape of work has changed “remarkably,” says MIT economist David Autor, who has produced a new study showing how much middle-paying jobs and incomes have receded in cities. From 1990 through 2015, the wage advantage for non-college workers in the most urban quartiles of the U.S. was chopped in half, with African American and Latino workers most affected by this shift.

“It used to be [cities] were a magnet for people who were less fortunate, fleeing discrimination or underemployment, and served as an escalator for upward mobility,” says Autor, the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT. But today, he adds, “urban workers without college degrees are moving into lower-paid services rather than higher-paid professional jobs. And the extent to which that is occurring is larger among Blacks and Hispanics.”

Even in the same locations, Blacks and Latinos are more affected by this shift. The wages of white workers without college degrees in the most urban quartile of the job market have risen slightly since 1980, compared to non-college workers in the least urban job markets. But for Black and Latino men and women without college degrees in those places, the reverse has happened.

“The urban wage premium has risen a bit for non-college whites, but fallen for everyone else without a college degree,” Autor says.

This wage stagnation also helps explain why many workers without college degrees cannot afford to live in big cities. Yes, home prices have soared and cities have not produced enough new housing. However, Autor suggests, “The change in wages alone would be sufficient” to price most non-college workers out of cities.

Autor’s new white paper, “The Faltering Urban Opportunity Escalator,” was released today in partnership with the Aspen Institute’s Economic Strategy Group. In examining the hollowing out of economically secure middle-skill jobs for non-college workers, the research also addresses a core topic of MIT’s Work of the Future task force, an Institute-wide project Autor co-chairs.

“The set of economically secure career jobs for people without college degrees has narrowed,” Autor says. “It’s a central labor market challenge that the Task Force is focused on: How do you ensure that people without elite educations have access to good jobs?”

What kinds of work?

To conduct the research, Autor drew on U.S. Census Bureau data and his own previous research examining the changing structure of urban labor markets in the U.S.

As Autor details in his report, in the U.S., as in most industrialized countries, employment has become increasingly concentrated in high-education, high-wage occupations, and in low-education, low-wage jobs, at the expense of traditionally middle-skill career jobs. Economists refer to this phenomenon as employment “polarization.” Its causes are many, rooted in both automation and computerization, which have usurped many routine production and office tasks; and in globalization, which has substantially reduced labor-intensive manufacturing work in high-wage countries. As polarization has advanced, workers without college degrees have been shunted out of blue-collar production jobs, and white-collar office and administrative jobs, and into services — such as food service, cleaning, security, transportation, maintenance, and low-paid care work.

In 1980, U.S. employment was roughly evenly divided among three occupational categories: 33 percent of workers were in relatively low-paying manual and personal-service jobs; 37 percent were in middle-paying production, office, and sales occupations; and 30 percent were in high-paying professional, technical, and managerial occupations. But by 2015, just 27 percent of the U.S. workforce was employed in middle-paying occupations.

That shift has mostly been felt by non-college-educated workers. More specifically, in 1980, 39 percent of non-college workers were in low-paying occupations, 43 percent were in middle-paying vocations, and 18 percent were in the high-paying, occupations. But by 2015, just 33 percent of noncollege workers were in the middle-paying occupations, a 10 percentage-point shift. About two-thirds of that change has moved workers into traditionally lower-paying jobs, occupations that require less-specialized skills. These jobs, accordingly, offer fewer opportunities for acquiring skills, augmenting productivity and pay, and attaining job stability and economic security.

A key finding of Autor’s work is that this change has been “overwhelmingly concentrated in urban labor markets,” as the paper notes. In the study, Autor analyzes 722 census-defined “commuting zones” (local labor markets) in the U.S. from 1980 through 2015, and finds that in the country as a whole, non-college urban workers with high school diplomas saw their wages fall by 7 percentage points relative to their non-urban equivalents; for urban workers who did not finish high school, the relative fall was even steeper, at 12 percentage points.

The jobs most affected are manufacturing and office clerical jobs, which have largely vanished from cities. As Autor’s study shows, these positions — along with administrative and sales jobs — made up a much bigger share of employment in cities than in non-urban areas in 1980. But by 2015, they represented a roughly equal share of employment in both urban and rural settings.

“Cities have changed a lot for the less educated,” Autor says. In the past, “non-college workers did more specialized work. They worked in offices alongside professionals, they worked in factories, and they were [performing jobs] they didn’t have outside of cities.”

Losing ground

Given the demographic composition of U.S. cities as a whole, any large shift in urban employment will affect African American and Latino populations, Autor notes: “African Americans and Hispanics are heavily represented in urban areas. Indeed, the Great Migration brought many African Americans from the South to Northern industrial cities in search of better opportunities.”

But as Autor’s study shows, African Americans and Latinos have lost more ground than whites with the same education levels, in the same places. Take again the top quartile of most-urban labor markets between 1980 and 2015. Among whites, Blacks, and Latinos, by gender, employment in middle-paying jobs among non-college workers declined sharply in this time period. But for white men and women, that employment decline was just over 7 percent, while for Black men and women and Latino men and women, it was between 12 and 15 percent.

Or consider this: Among workers with a four-year degree in the same urban settings between 1980 and 2015, the only group that saw a relative wage decline was Black men. In part, Autor says, that could be because even middle-class Black men were in more precarious employment situations than middle-class workers of other racial and ethnic groups, as of 1980.

“The black middle class … was more concentrated in skilled blue collar work, in clerical and administrative work, and in government service than non-minority workers of comparable education,” Autor says.

Still, Autor adds, the reasons for the relative decline may be deeply rooted in social dynamics: “There is no ethnic group in America that is treated more disproportionately unequally and unfairly than Black men.”

Push or pull?

While no social circumstance that pervasive has easy solutions, Autor’s paper does suggest setting an appropriately calibrated minimum wage in cities, which would likely erase some of the pay gap between whites and Blacks.

“There’s a lot of evidence now that minimum wages hikes have been effective,” Autor says. “They have raised wages without causing substantial job loss.” Moreover, he adds, “Minimum wages affect Blacks more than they affect whites. … It’s not a revolutionary idea but it would help.”

Autor emphasizes that boosting wages through minimum wage hikes is not a cost-free solution; indeed costs are passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices, and sharp hikes may tend to put low-productivity employers out of business. Nevertheless, these tradeoffs may be appealing given the falling earnings power of workers without college degrees — who constitute the majority of workers — in U.S. cities.

The current research also suggests that the crisis of affordability in many cities is more than a shortage of affordable housing. While many scholars have criticized urban housing policies as being too restrictive, Autor thinks the problem is not just that workers without four-year degrees are being “pushed” away from cities due to prices; the relative wage decline means there is not enough “pull” being exerted by cities in the first place.

“Cities have become much more expensive, and housing is not the only factor,” Autor says. “For non-college workers, you have a combination of changing wage structure and then rising prices, and the net effect is making cities less attractive for people without college degrees.” Moreover, Autor adds, the eroding quality of jobs for non-college urban workers “is in some sense a harder problem to solve. It’s that the labor market has changed.”

Autor will continue this line of research, while also working on MIT’s Work of the Future project along with the other task force leaders — Executive Director Elisabeth B. Reynolds, who is also executive director of the MIT Industrial Performance Center, and co-chair David A. Mindell, professor of aeronautics and astronautics, the Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing at MIT, and founder and CEO of the Humatics Corporation.

The MIT task force will deliver a final report on the topic this fall, having published an initial report in September 2019, which observed the economic polarization of the workforce, detailed technological trends affecting jobs, and contained multiple policy recommendations to support the future of middle-class work.

Peter Dizikes | MIT News Office

Press Contact

Abby Abazorius

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 617-253-2709

MIT News Office

source https://scienceblog.com/517227/cities-have-stopped-providing-middle-class-work/

0 notes

Link

The term “witch hunt” has renewed cultural and political resonance, largely because it’s one of President Trump’s preferred strategies for deflecting criticism and mobilizing his base. Since assuming office, Trump has tweeted some variant of the phrase “WITCH HUNT!” more than 120 times in response to the Mueller investigation and critics including the “Fake News,” congressional Democrats, Hillary Clinton, various intelligence agencies, former President Obama, and “leakers” within the administration itself.

These tweets reflect the modern usage of the term — as a metaphor that delegitimizes an investigation by calling out the partisan biases and ideological motives underlying accusations of wrongdoing.

But the use of the term “witch hunt” is more than just partisan maneuvering. It contains a gender dynamic that’s often overlooked, particularly when a man in a position of power identifies himself as the target of a witch hunt. Trump’s witch hunt cross-references other historical and contemporary witch hunts, where the role of gender and power is more visible and more explicit. Placing his witch hunt in this broader context shows that the witch hunt is still a tool used to shore up gendered notions of authority, power, and legitimacy.

Historian Christina Larner posed this question in response to estimates that about 80 percent of those accused of witchcraft in the European witch hunts of the 16th and 17th centuries were women. In other medieval witch hunts, like those taking place in Russia, the proportion of women was higher — between 95 and 100 percent. At the same time, the witch hunters, the clerical and secular authorities presiding over inquisitions and tribunals tasked with identifying and eliminating witchcraft practitioners, were overwhelmingly male.

Why did early witch hunts play out along such clearly demarcated gender lines? Historians attribute much of the focus on gender to the world’s definitive witch-hunting manual the Malleus Maleficarum, or Hammer of Witches, which established a strong link between womanhood and witchcraft.

In a chapter titled “Why is that Women are chiefly addicted to Evil superstitions?” the book’s Catholic authors draw on stories of Eve’s role in the fall of man to argue that women are the weaker sex and thus more susceptible to demonic influence and more inclined to form a sexual pact with the devil.

The Malleus Maleficarum also set forward detailed legal procedures to follow for the identification and prosecution of witches that relied primarily on religious and political authorities. As a result, most of the key players tasked with witch-hunting were men. Of course, women participated too — they made accusations, testified against other women, and suffered dramatic spectral possessions at public trials (as famously depicted in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible) — but their roles were relatively circumscribed when compared to men. Women were ancillaries to the prosecution side in formal witch hunt proceedings.

In practice, these witch hunts tended to single out particular kinds of women, namely gender-nonconforming women, who threatened a social system characterized by rigid gender roles. As Larner put it: “Witches are conspicuous. The women who went to the stake during the witch hunt went cursing, often for the crime of cursing.”

Overt sexuality, displays of ambition (i.e., “lust” for power) and failure to behave in a circumspectly feminine manner were taken as evidence of witchcraft in women. Because of this focus on weeding out gender-nonconforming women, many historians agree that the witch hunts of the early modern period were a tool for reinforcing male-dominated systems of authority.

The term “witch hunt” entered the American political lexicon in the 1950s, during the second Red Scare. Anti-communist sentiment ran high after World War II, and a number of political elites, notably Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R-WI), speculated that Americans faced communist “enemies within.” This sparked large-scale efforts to root out communists from the US government, organized labor, higher education, media, and the entertainment industry.

Historians estimate that between 1947 and 1965, 5 million federal employees were subjected to loyalty tests, which resulted in about 2,700 dismissals and 12,000 resignations. Few of those investigated turned out to actually be communists, and McCarthy’s name became synonymous with leveling trumped-up, unsubstantiated accusations of wrongdoing against one’s political opponents in a highly pressurized political climate.

McCarthy’s anti-communist witch hunts tended to target women. Women were overrepresented among defendants in federal loyalty cases, and agencies that employed a disproportionately large share of women were often singled out for close scrutiny. Historian Landon Storrs notes that evidence presented against female defendants took on a distinctively gendered tone. For example, keeping one’s maiden name, “needlessly” holding a high-paying job while married, and having a “dominant personality” were all grounds for suspicion of communist sympathizing, ostensibly because communists eschewed traditional gender roles.

This focus on women came on the tail of a large shift in the gender composition of the civil service sector that occurred during the New Deal and World War II. By 1947, about 45 percent of federal civil service employees working in Washington, DC, were women, making it the most integrated employment sector of the time.

Some conservatives feared that women would expand agencies and programs in ways that would allow American women more independence and autonomy. In this way, female civil servants represented an economic and social threat to traditional notions of American masculinity tied to breadwinning. Loyalty tests became a mechanism for enforcing norms associated with gender and heterosexual relationships.

Like the early modern witch hunts and the witch hunts of the McCarthy era, our modern witch hunts are tied up in beliefs about gender, sex, and power. Trump’s presidential campaign was highly gendered; research shows he was successful at activating hostile sexism among members of his base, who responded favorably to his hypermasculine self-presentation.

President Trump’s supporters, including many women, were not deterred by his comments on the Access Hollywood tapes nor by the 22 allegations of sexual assault made against him prior to Election Day. Polling data also demonstrates that Trump’s supporters strongly prefer a masculine national culture — two-thirds feel that American society has grown “too soft and feminine.”

For these reasons, Trump’s victory seemed to many like a national referendum on unapologetic hypermasculinity. Mueller’s investigation, as “the greatest witch hunt in American history,” challenges the legitimacy of Trump’s presidency, and in doing so also challenges the outcome of this referendum on American masculinity.

In historical perspective, Trump inverts the typical gender power dynamic we associate with the witch hunt. Traditionally, targets of the witch hunt didn’t conform to strict norms associated with gender or heterosexuality, whereas Trump strongly adheres to both. Past targets were typically vulnerable and were singled out by people with strong bases of economic or political power. Trump isn’t vulnerable in this way; he’s amassed tremendous personal wealth and sits in the Oval Office. As such, he’s a sharp contrast to the historical targets of witch hunts.

He is also on the wrong side of the mob. If we fall back on our Hollywood tropes of the witch hunt for a moment, we might image townsfolk sharpening their pitchforks and forming a mob to drag the witch to her fate. But we often see Trump presiding over a crowd, and the crowd’s chants have a prosecutorial bent: “Lock her up!”

Many of Trump’s favorite scapegoats are women: Nancy Pelosi, Hillary Clinton, Elizabeth Warren, and Dianne Feinstein. He claims to be the target of a witch hunt while mobilizing a mob against his partisan enemies, many of whom happen to be women. In these moments, the president seems to have more in common with witch hunters than with witches.

This shift in the gender dynamic associated with the witch hunt was also evident among supporters of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh when he faced accusations of sexual assault during his Senate confirmation hearings — such as the email blast from the Republican National Committee that included the phrase “STOP THE WITCH HUNT AGAINST JUDGE KAVANAUGH”; Sen. Lindsay Graham’s exasperated question, “Why don’t we dunk him in the water and see if he floats?”; and headlines like “Journalism Hits New Lows in Kavanaugh Witch Hunt.”

We can see the same pattern in the way the term is used to register opposition to the #MeToo movement. #MeToo is intimately tied in with Trump’s rise to power and has become a mechanism for women to register their disaffection with the president’s misogyny. Critics of the movement in Hollywood and the media have called it a “feminist witch hunt” that should be “left in the middle ages.”

Characterizing accusations of sexual assault as a witch hunt reframes the traditional power dynamic. Men in positions of authority are accused of sexual deviance or misbehavior, rather than women with comparatively less power. Labeling these accusations a witch hunt suggests they amount to an illegitimate power grab by women rather than a reflection of the widespread abuse of women by men in positions of power over them. In this respect, the term is used to support the status quo when it comes to sexual harassment — one in which sexual harassment is common and the men who harass women face few consequences for their misconduct.

While the 2016 election was a peculiar inflection point for the witch hunt, in that Trump’s co-option and usage of the terms affects some things about its meaning and broader usage, it remains a gendered narrative. Like many of the conversations we’re having this election cycle about American politics, the witch hunt is about our collective struggles to navigate tensions associated with gender and power.

Unlike in the past, our modern witch hunts are often invoked defensively by men in positions of power and authority. Recent events show that men with political and economic power can often rely on the idea of witch hunts to work for them, not against them. The witch hunt still uses institutional authority to enforce traditional gender norms and power relations.

Erin C. Cassese is an associate professor of political science at the University of Delaware and an expert contributor at Gender Watch 2018. Find her on Twitter @ErinCassese.

Original Source -> A political history of the term “witch hunt”

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Link

The president is the billionaire head of a global business empire, and his mostly millionaire Cabinet may be the richest in American history. His opponent in the 2016 election was a millionaire. Most Supreme Court Justices are millionaires. Most members of Congress are millionaires (and probably have been for several years).

On the other end of the economic spectrum, most working people are employed in manual labor, service industry, and clerical jobs. Those Americans, however, almost never get a seat at the table in our political institutions.

Why not? In a country where virtually any citizen is eligible to serve in public office, why are our elected representatives almost all drawn from such an unrepresentative slice of the economy?

This year, it might be tempting to think that working-class Americans don’t have it so bad in politics, especially in light of recent candidates like Randy Bryce, the Wisconsin ironworker running for the US House seat Paul Ryan is vacating, or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the former restaurant server whose primary election win over Democratic heavyweight Joe Crowley may go down as the single biggest election upset in 2018.

In reality, however, they are stark exceptions to a longstanding rule in American politics: Working-class people almost never become politicians. Ocasio-Cortez and Bryce make headlines in part because their economic backgrounds are so unusual (for politicians, that is). Their wins are stunning in part because their campaigns upset a sort of natural order in American politics.

Christina Animashaun/Vox

The figure above plots recent data on the share of working-class people in the US labor force (the black bar) and in state and national politics. Even in the information age, working-class jobs — defined as manual labor, service industry, and clerical jobs — still make up a little more than half of our economy. But workers make up less than 3 percent of the average state legislature.

The average member of Congress spent less than 2 percent of his or her entire pre-congressional career doing the kinds of jobs most Americans go to every day. No one from the working class has gotten into politics and gone on to become a governor, or a Supreme Court justice, or the president.

And that probably won’t change anytime soon. The left half of the figure below plots data on the share of working-class people in state legislatures (which tend to foreshadow demographic changes in higher offices) and the percentage of members of Congress who were employed in working-class jobs when they first got into politics. As a point of comparison, the right half of the figure plots data on the share of state legislatures and members of Congress who were women. (Of course, these groups overlap — a woman from a working-class job would increase the percentages in both figures.)

Christina Animashaun/Vox

The exclusion of working-class people from American political institutions isn’t a recent phenomenon. It isn’t a post-decline-of-labor-unions phenomenon, or a post-Citizens United phenomenon. It’s actually a rare historical constant in American politics — even during the past few decades, when social groups that overlap substantially with the working class, like women, are starting to make strides toward equal representation. Thankfully, the share of women in office has been rising — but it’s only been a certain type of woman, and she wears a white collar.

This ongoing exclusion of working-class Americans from our political institutions has enormous consequences for public policy. Just as ordinary citizens from different classes tend to have different views about the major economic issues of the day (with workers understandably being more pro-worker and professionals being less so), politicians from different social classes tend to have different views too.

These differences between politicians from different social classes have shown up in every major study of the economic backgrounds of politicians. In the first major survey of US House members in 1958, members from the working class were more likely to report holding progressive views on the economic issues of the day and more likely to vote that way on actual bills. The same kinds of social class gaps appear in data on how members of Congress voted from the 1950s to the present. And in data on the kinds of bills they introduced from the 1970s to the present. And in public surveys of the views and opinions of candidates in recent elections.

The gaps between politicians from working-class and professional backgrounds are often enormous. According to how the AFL-CIO and the Chamber of Commerce rank the voting records of members of Congress, for instance, members from the working class differ by 20 to 40 points (out of 100) from members who were business owners, even in statistical models with controls for partisanship, district characteristics, and other factors. Social class divisions even span the two parties. Among Democratic and Republican members of Congress alike, those from working-class jobs are more likely than their fellow partisans to take progressive or pro-worker positions on major economic issues.

These differences between politicians from different economic backgrounds — coupled with the virtual absence of politicians from the working class — ultimately skew the policymaking process toward outcomes that are more in line with the upper class’s economic interests. States with fewer legislators from the working class spend billions less on social welfare each year, offer less generous unemployment benefits, and tax corporations at lower rates. Towns with fewer working-class people on their city councils devote smaller shares of their budgets to social safety net programs; an analysis I conducted in 2013 suggested that cities nationwide would spend approximately $22.5 billion more on social assistance programs each year if their councils were made up of the same mix of classes as the people they represent.

Congress has never been run by large numbers of working-class people, but if we extrapolate from the behavior of the few workers who manage to get in, it’s probably safe to say that the federal government would enact far fewer pro-business policies and far more pro-worker policies if its members mirrored the social class makeup of the public.

As the old saying goes, if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.

Now, defenders of America’s white-collar government will tell you that working-class people are unqualified to hold office, and that voters know it and rightly prefer more affluent candidates.

Alexander Hamilton said it (“[workers] are aware, that however great the confidence they may justly feel in their own good sense, their interests can be more effectually promoted by the merchant than by themselves”). Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists have said it (“voters repeatedly reject insurrectionist candidates who parallel their own ordinariness … in favor of candidates of proven character and competence”). Donald Trump has said it (“I love all people, rich or poor, but in [Cabinet-level] positions, I just don’t want a poor person.”).

However, this line of reasoning is flat wrong. The raw personal qualities that voters tend to want in a candidate — honesty, intelligence, compassion, and work ethic — are not qualities that the privileged have a monopoly on. (In fact, two of the traits voters say they most want in a politician, honesty and compassion, may actually be a little less common among the rich.)

When working-class people hold office, they tend to perform about as well as other leaders on objective measures; in an analysis of cities governed by majority-working-class city councils in 1996, I found that by 2001, those cities were indistinguishable from others in terms of how their debt, population, and education spending had changed.

When working-class people run, moreover, they tend to do just fine. In both real-world elections and hypothetical candidate randomized controlled trials embedded in surveys (which help to rule out the so-called Jackie Robinson effect), voters seem perfectly willing to cast their ballots for working-class candidates.

The real barrier to working-class representation seems to be that workers just don’t run in the first place. In national surveys of state legislative candidates in 2012 and 2014, for instance, former workers made up just 4 percent of candidates (and around 3 percent of winners).

So why do so few workers run for office? I’ve been researching this question for the past decade, and I think the answer is right under our noses: campaigns.

Let me say from the outset that I love our democracy, and I wouldn’t want to live in a country that selected political leaders any other way. But American democracy isn’t perfect — no system of government is — and one of the side effects of selecting leaders via competitive elections is that groups with fewer resources are at a huge disadvantage.

In democratic elections, people can only be considered for office if they take time off work and out of their personal lives to campaign. Even in places where candidates don’t spend a lot of money on their campaigns, they still put in a lot of time and energy — any candidate will tell you that running was a significant personal sacrifice. They give up their free time. They give up time with their families. Many of them have to take time off work.

For politically qualified working-class Americans, this feature of elections seems to be the barrier that uniquely distinguishes them from equally qualified professionals. In surveys, workers and professionals alike hate the thought of asking for donations. They say that the thought of giving up their privacy is a downside. They express similar concerns about whether they are qualified.

But it is the thought of losing income or taking time off work that uniquely screens out working-class Americans long before Election Day. When the price of competing is giving up your day job (or a chunk of it), usually only the very well-off will be able to throw their hats into the ring.

But couldn’t party and interest group leaders help working-class Americans overcome these obstacles? Couldn’t foundations create special funds to encourage and support candidates from the working class?

Of course. But they usually don’t. The people who recruit new candidates often don’t see workers as viable options, and pass them over in favor of white-collar candidates. In surveys of county-level party leaders, for instance, officials say that they mostly recruit professionals and that they regard workers as worse candidates. Candidates say the same thing: In surveys of people running for state legislature, workers report getting less encouragement from activist organizations, civic leaders, and journalists.

The reasons are complicated. Some party leaders cite concerns about fundraising to explain why they don’t recruit workers, for instance, and in places where elections cost less, party officials really do seem to recruit more working-class candidates. However, by far the best predictor of whether local party leaders say they encourage working-class candidates is whether the party leader reports having a lower income him- or herself and whether the party leader reports having any working-class people on the party’s executive committee.

Candidate recruitment is a deeply social activity, and political leaders are usually busy volunteers who look for new candidates within their own mostly white-collar personal and professional networks. The result is that working-class candidates are often passed over in favor of affluent professionals.

What about foundations, reformers, and pro-worker advocacy organizations? Couldn’t they help qualified working-class Americans run for office?

Of course. But they usually don’t. There are models out there for doing so, actually — the New Jersey AFL-CIO has been running a program to recruit working-class candidates for more than two decades (and their graduates have a 75 percent win rate and close to 1,000 electoral victories). But the model has been slow to catch on in the larger pro-worker reform community.

To the contrary, the pro-worker community has focused on reforms aimed at addressing the oversize political influence of the wealthy that have historically tended to look at on inequalities in political voice, imbalances in the ways that citizens and groups pressure government from the outside. We’ve heard the same story for decades: If we could reform lobbying and campaign finance and get a handle on the flow of money in politics, the rich wouldn’t have as much of a say in government. If we could promote broader political participation, enlighten the public, and revitalize the labor movement, the poor would have more of a say.

The key to combating political inequality, in this view, is finding ways to make sure that everyone’s voices can be heard — and the idea of giving workers influence inside government has never been a part of the mainstream reform conversation.

That may change someday, and I hope it will — especially considering the practical and political roadblocks facing other reforms like increasing voter turnout and reforming the campaign finance system. The opportunity to go down in history as the Emily’s List of the working class is just waiting there for some forward-looking organization.

In the meantime, what can you do? A lot, actually.

First, look up what the candidates on your ballot do for a living. Many people get sample ballots in the mail, or have the option to look them up online. Create your own occupational profile of your ballot — find out how your candidates earn a living (or if they work full time in politics, find out how they earned a living before). While you’re at it, look at the representation of women, people of color, people with disabilities, or any other social group you think is important. When you’re done, post the results on social media. The virtual absence of working-class people in American political institutions is something that people take for granted. Challenge that.

And if you aren’t happy with the mix of people on your ballot, contact your local party leaders and let them know that you would support a more economically diverse slate of candidates. Be nice to them — most local party leaders are volunteers with day jobs just doing their best — and express appreciation for all the hard work they do to keep your local party running. But also let them know that you’d like to see more people with experience in working-class jobs on your ballot. And if you’re willing and able, offer to help however you can.

When working-class candidates run, stick up for them. If they’re people you can get behind, donate to their campaigns, or send them encouraging notes, or talk about them positively to your friends. If you’re able, offer to volunteer for their campaigns. Working-class candidates start at a disadvantage, and they don’t get as much support from political insiders. Reach out to them and let them know that you see the sacrifices they’re making. If you’re one of the rare Americans who has a working-class candidate on the ballot, and if you support them, offer to help.

Regardless of whether you find a working-class candidate to support, call out social class stereotypes and prejudices when you see them in political media. When workers run, journalists often express amazement, or talk about them in class-coded ways that demean their intelligence and character. (The CNN coverage of opposition research on Randy Bryce is a great example.) When media outlets cover working-class candidates, ask yourself: Are journalists treating the other candidates in this race the way they’re treating this candidate? Would they say that about a candidate with a white-collar job and a big house in the suburbs? If the answers are no, write to their editors, or call them out on social media. Demand political news coverage that doesn’t slide into social class stereotypes.

Finally — and this is the big ask — set up an organization to recruit and train working-class candidates. Contact party leaders and interest groups in your area and organizations that work directly with working-class people, and ask what it would take to create a program to encourage workers to run for office. Start small — ask if you can help put on a simple candidate training program for workers in your area. Make it a one-time event. It will be easier than you think. Then do it again. And again. Give it a name, find funders, and make it your life’s work. (I told you it was a big ask.)

Campaigns have a built-in bias against working-class candidates. Call it an unintended consequence, a glitch in an otherwise admirable system, a side effect. Whatever it is, it isn’t a necessary evil, or an inevitability. Politicians work for you. If you don’t like what the millionaires have done with your government, fire them.

Nicholas Carnes is the Creed C. Black associate professor of public policy and political science at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy. He is the author of The Cash Ceiling: Why Only the Rich Run for Office — and What We Can Do About It. Find him on Twitter @Nick_Carnes_.

Original Source -> Working-class people are underrepresented in politics. The problem isn’t voters.

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes