#and he’s behaving under the assumption that ‘morals and the federation’ is not a very strong power balancing system

Text

(It’s time for a 4halo ramble and analysis into their current relationship! Everything that follows is about the characters, I’m not using the q! because I’m lazy. I also want to repeat that while I am a 4halo shipper this entire rant is me explaining why I don’t want them to get together right now or anywhere in the near future. I don’t really consider this 4halo neg but let me know if you want me to tag it as such - they have the chemistry and in a distant future I could see it - but the fluffy 4halo that everyone seems to be imagining right now? I can’t see it happening. Toxic 4halo is another story entirely though and not what this ramble is about)

Okay you have been warned (THIS IS LONG):

not saying I’m not a huge 4halo enjoyer because. I am. But I do hope they don’t actually “become canon” or get into a relationship for the foreseeable future. Because the only realistic way that will end is in a giant, heart-wrenching break-up after like. 2 weeks. And I don’t see the ship recovering from that I’m gonna be honest.

Look. They can barely communicate as they are right now, any kind of committed relationship between them would end in fire and brimstone - especially when you take into account the power imbalance that is already causing problems.

Forever has not apologized for jailing Bad, even though Bad has asked for it (a rare show of communication on his part) and he might not apologize ever because he thinks he’s in the right. Somehow Cellbit is the only one to have apologized despite being the one calling for Bad’s head the most during the actual furniture incident. Anyway, Bad knows Forever thinks he’s in the right. And Bad also knows Forever wielded his presidential power to keep him jailed - so if Forever’s not sorry and he believes he was right, what’s to stop him from doing it again - in Bad’s mind, that is. There are actually quite a few things keeping him from doing it again, chief among them being that he doesn’t want to lmao. But Bad wouldn’t know that, would he?

I just- The imprisonment hurt Bad’s trust in everyone so badly that he destroyed every waystone in his base - and he when he found out Pac had someone gotten in anyway, he destroyed the waystone again. I don’t think people understand how long he’s been contemplating doing that. I don’t think people understand how many times he’s decided against destroying his waystones. It takes a pretty big fuck up to get him to do that. It takes a fuck-up of pretty tremendous proportions. And he did that last bit with Pac extremely recently too, which means he hasn’t forgotten.

And that - the whole furniture fiasco - that’s not a misstep that will just smooth over if Bad and Forever just care about each other hard enough. They already care about each other deeply - it didn’t stop the conflict. It’s not something everyone can just sweep under the rug with the power of love and no actual communication. Or at least I hope it’s not. It shouldn’t be. Any relationship the two get into right now will be steeped in distrust and wariness on Bad’s part due to the amount of power Forever can choose to use against him at any moment. And even if Forever hadn’t imprisoned him, that would still probably be the case, albeit to a much lesser extent. But Forever did imprison him, so now Bad’s not only wary of Forever turning on him in a hypothetical sense - he has past experience with that exact scenario. He has reason to distrust. It’s not paranoia in this instance; it’s genuine, rational distrust, which is even harder to alleviate.

By the way, that’s not even taking into account that Bad now knows of the existence of a drug that can brainwash Forever into potentially abusing his power against his own will. Think about how scary we all thought the drug-induced marriage proposals were. Think about how much scarier it would’ve been if Bad and Forever had actually been dating at the time. I’m not going to get into the risus potion here, or what implications it has for Bad’s trust in Forever - or more accurately, the trust he has in Forever’s position of power - because that’s too fucking complicated for my silly brain right now and this is long enough.

So basically: how is a relationship between a president and an anarchist supposed to work? Is Bad supposed to shut up, abandon his core principles, and do whatever Forever wants? When he opposes/attempts to help Forever improve the voting system he’s not being ‘immature’ - he’s acting in perfect accordance with his own belief system. There are points where he does act antagonist in an immature manner but in those instances he is very obviously being dramatic on purpose (and Forever does it as well). Him thinking Forever’s voting system isn’t fair isn’t him being immature, it’s just him being politically opposed. And Forever - what about Forever? Is Forever supposed to throw away his entire presidency? Oh, Bad’s an anarchist so that means Forever has to give up everything he’s worked so hard to accomplish, all the plans he has, all the good he’s desperately trying to do despite the fact that the nature of his position is scaring his loved ones away? He’s supposed to let everyone boss him around? Just because his crush hates government? Really? See, none of these options sounds particularly healthy, but their friendship isn’t even healthy right now so I can’t see them somehow reaching a better alternative.

Idk if you couldn’t tell I don’t like it when people non-jokingly boil down Bad and Forever’s political arguments as something that’ll be solved if one of them gives in or apologizes. Because they won’t. Because neither of them is wrong. Forever was partially right when he told Bagi that nothing he does as president will ever satisfy Bad - Bad is an anarchist, the fact that a government has been forced on him in the first place is already a fundamental problem - and that’s not wrong of him! It’s a genuine difference in beliefs and neither of them is wrong! Bad is not somehow automatically wrong because he’s an anarchist, and Forever is not somehow automatically wrong because he’s the president. Grrr bark woof grr bark, etc… you get what I mean.

(TLDR; if 4halo becomes canon right now it’ll crash and burn instantly and kill everyone on board which I don’t want to happen. Therefore I don’t wish for it to be canon.)

#please remember that while forever has the title of president the position is actually comparable in power to that of a king#he can actually do whatever he wants the only thing stopping him is his morals and the federation#and while q!forever himself may not realize that#q!Bad definitely. DEFINITELY does#and he’s behaving under the assumption that ‘morals and the federation’ is not a very strong power balancing system#partially because of his own moral code and what he would do in that position but even still he Knows what ‘president’ actually means#qsmp#qsmp analysis#4halo#taking minecraft political relationship drama WAY too seriously#q!badboyhalo#q!forever#neither of my perfect boys have ever done anything wrong ever and I refuse to accept otherwise

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

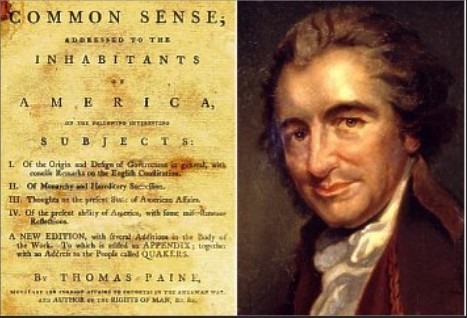

Common Sense

Thomas Paine’s claim to be acclaimed as “the father of the American Revolution” rests in no small part on the 49-page pamphlet Common Sense he published on January 10, 1776, as the War of Independence entered its second year. It was a huge success—when its press run is considered in proportion to the population at the time, Common Sense remains the best-selling American book ever—and was not only read quietly by people in the privacy of their homes but was actually declaimed aloud in taverns and in public gathering spots as a way of martialing public support for the effort to gain independence for the thirteen colonies. I read it first in high school and still remember imagining myself as an eighteenth-century high school student being moved to embrace the insurgency because of Paine’s bold, persuasive argumentation. (I was that kind of eleventh grader.)

Paine packs a lot into relatively few pages, but his main argument is that sometimes you have to step aside from fossilized allegiance to past attitudes, timidity regarding the possible consequences of enlightened action, and the inertia that results when people choose to mimic their own past behavior rather than to act as thoughtful, self-directed individuals. He concedes, for example, that it is natural and normal for people to feel a deep sense of allegiance to the individuals that legally govern them. But when those individuals—he was writing unambiguously about the British—when those individuals themselves behave in a way that belies their commitment to the wellbeing of the governed, then common sense dictates that that allegiance be set aside and a finer, nobler, and more enlightened path forward into the future be taken. Similarly, he notes, it is natural to feel that one’s own nation’s armed forces are in place to protect and make secure the citizenry. But when that army is used not to buttress the natural rights of the citizenry to thrive in their own places and to make them safe, but to force them to submit to unfair, unprincipled, and unjust laws imposed upon them from without, then common sense dictates that that natural inclination to think of one’s own army as being on one’s own side needs itself to be set aside and replaced with a set of emotions more related to reality.

It’s a stirring read and one of the truly essential works for any who would understand our nation’s founders and the mindset of the American people (or rather, the future American people) on the eve of revolution. If you haven’t read it, click here for a very legible, clearly laid-out online version. I mention Common Sense today, however, not specifically because of its role in our nation’s history, but because I wish to apply its chief argument to our current reality by asserting, in Paine’s style, that sometimes you really do need to set aside your priorly held beliefs and assumptions and choose instead to look out at the world through the lens of self-generated common sense.

This week’s Supreme Court decision regarding the legal meaning of the text in Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that referenced discrimination imposed on the discriminated-against party “because of sex” is a good example of how this notion of this could and should work. It goes without saying that the framers of the act were thinking more about gender-based discrimination than the kind that turns on the discriminated-against party’s sexual orientation. And Justice Gorsuch conceded that too, going so far as to address that particular point in his majority opinion and to concede that the act’s framers would probably not have anticipated the extension of their law to cover discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Nonetheless, he wrote—and this is key—that “the limits of the drafters’ imagination supply no reason to ignore the law’s demands.” That, I think, is common-sense thinking at its most basic level.

And, indeed, the counterargument as set forth in Justice Samuel Alito’s dissent (in which he was joined by Justice Clarence Thomas) was based precisely on the repudiation of Justice Gorsuch’s argument and argued instead that the fact that the act’s framers almost definitely did not mean to outlaw anti-gay discrimination makes it somewhere between spurious and wholly illegitimate for the Court retroactively to assign that meaning to their words. None of the principal players is alive today, so we can’t ask if they would approve of extending their legislation to protect the rights of gay citizens. Nor, obviously, can we travel back to 1964 to pose that question to legislators then all among the living. But—and this is the real point—we also cannot invite them to 2020 to see what has become of the world that they inhabited more than half a century ago and then either to revise or not revise their original intent. And so we are left with no real option other than to rely on common sense to tell us how best to approach the issue at hand and whether or not it makes sense to apply Title VII in the way the Supreme Court did earlier this week. And that is why I—who also doubt that the framers of the 1964 act were specifically thinking about anti-gay discrimination when they referenced discrimination “because of sex” in the text of the Act—think the Court’s decision was reasonable and just.

This notion—that the way to deal with the legal heritage of bygone centuries is to apply common sense to the laws under consideration and then to focus not on what the individuals responsible for their original formulation meant in their day but on what we conclude they would have meant if they were present to observe our world and to legislate in its regard—this notion is not only familiar and logical to me, but serves as perhaps the most basic single principle of Jewish law.

Outsiders are sometimes amazed that, for all the Torah is venerated endlessly as the word of God, we specifically do not make legal decisions based solely on the laws presented therein. We do not, for example, sanction any number of things that Scripture endorses as reasonable features of societal living. Slavery itself would be the best example. But there are also many others, including the notion of executing disobedient adult children, that were simply and universally set aside because the moral universe in which they were conceived is simply not the one in which Jewish people today live. The Torah talks about the specific way in which a virile soldier can force an attractive female prison-of-war into his bed, but there is not a single authority anywhere in the Jewish world—with no exceptions of any sort—who would dream of countenancing that kind of behavior today.

All of the above derive from a world so totally different from our own that applying them to modern society would result, not in the sanctification of God’s name, but in its profanation. But, of course, the question is not whether any of the above is true, but what specific criterion we are to use as we review ancient law and determine what to jettison and what to retain, what to insist remain incumbent upon us and what blithely (or not blithely) to allow to fall into timely desuetude.

The ancient sages who labored away at the science of Jewish law in the study halls of old imagined themselves being guided by the spirit of the living God. But, of course, none of those great rabbis actually was a prophet in the technical (or any) sense—and what they meant was that they perceived the common sense—the amalgam of realism, insight, intelligence, and moral bearing—they brought to the issues before them for adjudication, that common sense itself was the mode in which God speaks today to people willing to listen and eager to live lives in sync with divine values. And so they proceeded to legislate laws in apparent contravention of the plain meaning of Scripture as well as laws that developed Scriptural ideas in directions that seem unrelated to the plain sense of the original biblical text.

Common sense is what is called for in any number of contexts today. Extending federal anti-discrimination protection to a class of people that regularly experiences workplace and non-workplace discrimination is only to use common sense to amplify the clear sense of an older piece of legislation. (Invoking the “because of sex” clause in the Civil Rights Act to argue against the right of shopping mall owners to maintain separate restrooms for men and women, on the other hand, seems to me to fly in the face of common sense.) Working to guarantee that the nation’s police forces function in a way that generates trust among all segments of society rather than resentment, let alone outrage, is also just common sense. (Dismantling police forces without a clear sense of how to maintain order and safety in the nation’s streets in their absence, on the other hand, is an example of acting contrary to common sense.) Renaming army bases and schools named in honor of individuals who led armies into war with the specific aim of defeating and dismantling the republic seems like common sense to me. (But considering Theodore Roosevelt in the same category as Jefferson Davis seems to fly in the face of common sense. Woodrow Wilson [click here], on the other hand, not so much.)

0 notes

Text

THE CURRENCY, POWER

[Note: If the reader has taken up reading this blog with this posting, he/she is helped by knowing that this posting is the next one in a series of postings. The series begins with the posting, “The Natural Rights’ View of Morality” (February 25, 2020, https://gravitascivics.blogspot.com/2020/02/the-natural-rights-view-of-morality.html). Overall, the series addresses how the study of political science has affected the civics curriculum of the nation’s secondary schools.]

To this point, this blog has reviewed what the political world looks like through the natural rights perspective. As far as a theoretical view, the political systems model was central for political scientists during the decades of the mid twentieth century. Shortly, this blog proceeds with an overview of the methodology this approach promoted and how those methods reflected the general adoption of an approach known as behaviorism.[1]

This bias has further influenced the portrayal of government in American civics courses. That is, it reflects the market orientation of how Americans have come to see governance and politics. As described so far, the political system has multiple parts which interact in order to provide governmental services. These services are distributed through a competitive process.

Those who gain the benefits derived from those services do so because they can exert more power than others. Educators who instruct students about this process, therefore, are teaching their students about the exercises of power. Unfortunately, this effect does not extend to highlight this currency; it is assumed without giving its proper due.

So, the language they use might not be so blunt, but that is what they are teaching. One can ask, what is power in this social sense? The definition used here is: power is the ability of a person or a group, A, to get a person or a group, B, to do something B would not do otherwise.[2]

For example, if one, in an agitated way, walks into a room, sees another person sitting comfortably on a lounge chair and yells, “Get up,” and that person stands, that is an incident of power if one assumption is true. The assumption is that the other person was not about to stand up on his/her own accord to, say, get a cup of coffee. That is, that B was content to continue his/her rest.

This silly example is important because it illustrates how potentially difficult it is to measure power – only the lounging person knows what is going on in his/her mind and what he/she wants to do or is about to do. At its base then, this business of analyzing politics has a bit indetermination to it, but that does not seem to humble those who conduct much of what is called behavioral studies – more on this below.

With a definition in hand, a further step in conceptualizing power is to look at a categorizing scheme that identifies types of power. John R. P. French and Bertram H. Raven identify five types based on the motivation that someone would have to do something he or she would not want to do otherwise – that is, the mental states that would lead one to yield to the wishes of someone else.

This is bit ironic since behavioral studies claims to stand clear of such mental content – after all, they claim what is studied is what people do, not what they think and feel. But when one wants to wield power, costs are involved and if certain strategies are geared to take advantage of what people are apt to acquiesce to, then one has to speculate as to motivations on the part of the governed or ruled.

So, there are mental perceptions or expectations of coercion, reward, legitimacy, expertise, or reference (known, in turn, as coercive power, reward power, legitimacy power, expert power, and referent power).[3] This conceptualization is not only applicable to behavioral studies, but equally apply to either federal theory based-studies or the studies based on other constructs – power is that central to politics and political behavior. It is the currency of politics.

For purposes here, this account reduces power to three types: avoidance of punishment, seeking reward, and a sense of duty. One should consider, when utilizing the systems model, there are winners and losers and this, in turn, creates issues. No matter how small in dimension a political engagement happens to be, those who are engaged in it are participating in a process of competition. They conduct these competitive activities in the context of a system, a conglomeration of parts and actors that to some large degree, is organized and is intra-active.

There are actors who are in positions to make distributive decisions and there are actors who are vying for sought after gains in the form of policies, waivers, or payouts. In the vying for gains (desired outputs), the engaged actors can very well hold and promote competing political values and aims in the form of the preferred policies they are seeking.

Often, these actors, whether in positions of authority or not (some might enjoy highly influential positions without holding formal government office), hold a position of a relative level of power to influence or to make decisions that revolve around the differences between competing values and preferences. This exercise in power usually reflects negotiating among the various interests the “players” in a competition might have. The decision can be not to decide, to decide in favor of one or a combination of interests, or to compromise on a policy.

The exercise of power determines which way it goes. In the natural rights view, each participant is only concerned with extending that participant’s interest to the greatest extent possible at the least cost possible. For better or worse, this is how the system formulates “consensus” and arrives at a policy decision.

Players are apt to exercise power in all three forms. It metes out rewards and punishments and it also solicits a sense of duty and obligation. Therefore, central to this whole process are the authoritative decisions that determine whose values will be honored – catered to – and whose will not.

In addition, a study of this process (be it by decision-makers, competitors, or academics) entertains questions about how legitimacy is maintained even among the “losers” of a political competition. After all, there is always tomorrow, and the system needs to maintain its players playing by the rules – rules that need to be of benefit to all.

While this whole process refers to the organizational workings of groups and government, the systems approach focuses on the behavior of individuals within that structure who act from motivations of self-interest. Obviously, irrespective of the systems model emphasis on the individual – basic unit of analysis – any study of politics must account for collectives such as groups, associations, organizations of varying formalities, and governing processes.

But the political systems model, as it has already been emphasized, accommodates political analysis of these collectives under the demands of individual participants behaving in such a way as to advance each actor’s own individual interests.[4]

One should remember that how a person defines his/her self-interest can vary from person to person. A person can want monetary benefits or reputational accolades or artistic recognition or athletic prowess, etc. But however, one defines it, the systems approach – much in line with Machiavelli thinking[5] – sees this as the determining motivator in how he or she behaves politically.

A vivid example at this point helps. That would be New York City's legendary Robert Moses, who was the central official determining the winners of New York’s political scene from the 1930s into the 1960s. An extended quote from an interview with Moses' biographer, Robert Caro, gives one a taste of what is being described:

[For a highway, bridge, tunnel, park, etc.] Moses gave the contracts, the legal fees, the insurance premiums, the underwriting fees, and the jobs to the individuals, corporations, and unions who had the most political influence. So they all had a vested interest in seeing that his project was built. Therefore, if the people of a neighborhood, or their assemblyman or congressman, or a mayor or governor, tried to stop one of his projects, they would find themselves confronted by immense pressure from the very system they were a part of. A huge public work – a bridge or a tunnel or a great highway – is a source of raw power, if it is used right, and no one ever used power with such ingenuity, and such ruthlessness, as Robert Moses.[6]

Power is not limited to government. Power is potentially exercised in any social institution – businesses, churches, schools, medical facilities, legal firms, etc. – or any individual. Given this fact, one can begin to understand that politics is ubiquitous. The former popular TV show, The Good Wife,[7] dedicates a lot of its story lines to the political power plays within a legal firm upon which the series is based. But examples can also be seen in everyday life.

During a recent Christmas season, the postal service ran an ad which depicted a husband and wife trying to decide who was going to tackle which holiday chore. The wife says she will go to the mall if the husband takes care of mailing the gifts. The husband immediately says that he will go to the mall because dealing with postage and the post office is a nightmare.

He grabs the keys and runs to the car for his trip to the mall. Just then the postman walks up and explains to the wife that sending packages is easy. She responds with a wink, “I know.” The postman says, “Oh, you're good.” Power comes in many different guises and being the recipient or the victim might often go unnoticed.

What the last various postings try to communicate is not how civics is taught. Future postings will address that. What they to do try is to communicate a view of politics that has served as an overall understanding of politics that civics educators, including textbook authors, have brought to the task of planning and implementing their curricular ideas. How these images have been interpreted needs to be reviewed and will serve as topics of future postings.

[1] This writer has also seen this term referred to as behavioralism. Apparently, the term behaviorism refers to the analysis of behavior in psychology, while behavioralism is a term used in political science designating the study of political behavior. Both terms are used here interchangeably.

[2] Andre Munro, “Robert A. Dahl: American Political Scientist and Educator,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, February 1, 2020, accessed February 12, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-A-Dahl .

[3] Coercive power occurs when a person does something to avoid a punishment; reward power occurs when a person does something to gain a reward; legitimacy power occurs when a person does something out of a sense of duty; expert power occurs when a person does something because he/she is told to by a person who he or she believes to have some expertise, such as a doctor or lawyer; and referent power occurs when someone does something to be associated with someone, group and/or something.

[4] To be clear, a lot of the analysis might very well study group dynamics. The point is that even with this level of analysis, the basic assumption is that each participating actor will strive to advance his/her self-interest.

[5] See posting, “Foundations of the Natural Rights View,” March 10, 2020, accessed March 19, 2020, https://gravitascivics.blogspot.com/2020/03/foundations-of-natural-rights-view.html .

[6] Ric Burns and James Sanders, New York: An Illustrated History (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), 462.

[7] Robert King and Michell King (creators and producers), The Good Wife, CBS (a television series), 2009.

#power#politics#Robert A. Dahl#John R. P. French and Bertram H. Raven#political systems#civics education#social studies#political science

0 notes

Text

A National Thanksgiving: President Washington and America’s National Holiday

Editor’s note: This originally appeared on Thanksgiving Day, 2014.

Thanksgiving is a peculiar holiday, at least in the modern world. Its roots are religious, and the American nation is, at least in law, secular. Its very name speaks of thanks, or gratitude, and gratitude is an ancient virtue. Indeed Aristotle speaks highly of it. Even so, or perhaps for that reason, it is very American. In his Thanksgiving address in 1922, President Coolidge called it “perhaps the most characteristic of our national observances.” He was not wrong for, as Chesterton wrote, America is “a nation with the soul of a church,” and Abraham Lincoln called us an “almost chosen people.”

The holiday reminds us, in other words, of the peculiar character of the American nation, and of the President’s role in it. Strictly speaking, to be an American is to be an American citizen. When one calls someone an American, the first definition one usually has in mind is political. By contrast, when one says that someone is Chinese or Turkish, the first thought is of an ethnic or racial identity. Even so, there is an American culture. Hence it is very common to say that something is “very American.” Thanksgiving itself deserves that moniker. Is it a constitutional observance? That’s an open question.

In this holiday we see how the peculiar character of the Presidency compliments our exceptional nationality. Constitutionally speaking, the President is merely the American CEO. His job is to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” and in his oath, he swears to “execute the office of the President” and pledges to “preserve, protect and defend the constitution of the United States.” The oath says nothing about the American “nation.” Indeed the word “nation” does not appear in the Constitution, except in Article I, Section 8 when discussing relations with “foreign nations” and the “law of nations.” Strictly speaking, the President’s job is to put into effect the laws that Congress passes and to defend the “supreme law of the land.” Even so, the President is, in fact, head of state, and the leader of the American people. It is no surprise that the American president has, in time, acquired the trappings of a monarch—think of the entourage he travels with, the way he’s treated at the State of the Union address, the language with which we discuss the “White House’ and its parts, such as the “West Wing.” And a monarch is more than a CEO. He is the leader of the nation, in the classical sense of the nation.

George Washington set the tone for the office in many ways, none more so than in his Thanksgiving Proclamation, given in October, 1789, seven months after he took the oath of office. Why have such a proclamation at all? Where in Article I, Section 8 (the section that lists the powers the people gave the federal government) is the power to proclaim a federal holiday? In 1791 James Madison would criticize Alexander Hamilton’s assertion that the U.S. government has the authority to create a national bank, for nowhere in the Constitution did the people give the federal government the right to create a bank or to create a corporation (an entity that had traditionally been regarded as a “person” in the eyes of the law). And fourteen years later, the Louisiana Purchase would tie President Jefferson in knots, for nowhere did the people give the U.S. government the right to acquire territory. Yet Madison lost the national bank argument in 1791 and by 1816 he had changed his mind about its constitutionality. Meanwhile, Jefferson didn’t stop the Senate from ratifying the Louisiana Purchase. In other words, he and Madison implicitly accepted that there are some powers that belong to government due to the nature of the thing, and when the people created the U.S. government they, of necessity, allowed it those powers without which no government can function.

The authority to proclaim a Thanksgiving might seem trivial to us—mere words, and an idle declaration. But it is, in fact, fraught with meaning, for the assumption of such authority highlights the degree to which a President is, by nature, much like a monarch—albeit an elected one. Similarly, it points us to the limits of secular nationalism.

Consider President Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamation. He begins with the universal “duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favor.” But then he stops, as if he knew some might ask why the President is involved. Washington goes on, “Whereas both Houses of Congress have, by their joint committee, requested me ‘to recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a a form of government for their safety and happiness.’” Congress asked Washington to proclaim the day. An interesting request. Congress did not pass a law proclaiming a day of Thanksgiving. Such an act may, according to some constructions of the Constitution, have crossed over into an establishment of religion. Instead, they have merely asked the President to “recommend” such an observance to the people. But if it’s not a law, wherefore does the authority come from? It must adhere in the nature of the thing.

What is the power of a Presidential “recommendation”? Quite a bit, actually. And that is because the President is, as a practical matter, a national father figure. Those of us who are theoretically minded may fuss and fume that there is nothing in the Constitution suggesting such a role, and it is certainly true that there are many Americans who do not see it that way. It is nonetheless true that the President has always had such authority for a significant portion of the country. Even those who object to a particular President or his policies are often reacting as an unhappy child. And that is why a Presidential “recommendation” even of a merely ceremonial sort (I am not referring to the modern practice of the President or his minions “recommending” to businesses or Universities that they adopt certain practices. There is no implicit Presidential “or else” in this kind of proclamation) is simply the nature of the thing. A few states tried operating without a unitary executive in the years after 1776. The experiment was a failure. By the early 1790s, even Pennsylvania gave up on the effort. And once there is such an executive for the nation as a whole, he becomes “his elective majesty” even if we Americans are loathe to admit it.

That is what is so significant about the opening line of Washington’s Proclamation. He speaks of the “duty of all nations.” Such a declaration implies that nations are all alike in some ways. No nation is or can be exceptional in that regard. A nation, by nature, is a being in a moral universe. In the middle of the Thanksgiving Proclamation, Washington points back to the Declaration of Independence, noting that Americans are grateful “for the peaceable and rational manner in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness.” Americans should be grateful for the American experiment, the effort to show that men are capable of creating governments based upon “reflection and choice” as the first Federalist puts it. Even nations with governments under constitutions that are delegations of powers by the people cannot change the nature of the thing. And that means that national morality is a fundamental concern. At the start of the Defence of the Constitutions John Adams would link the two: “The people of America have now the best opportunity and the greatest trust in their hands, that Providence ever committed to so small a number since the transgression of the first pair. If they betray their trust, their guilt will merit even greater punishment than other nations have suffered, and the indignation of heaven.”

As Washington noted in his First inaugural Address, nations and individuals alike are judged by a common standard. The Universe being moral, nations that stink with injustice will, almost invariably inevitably (the ways of the Almighty being mysterious) suffer, just as individuals who do evil are punished, “since there is no truth more thoroughly established than that there exists in the economy and course of nature an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness; between duty and advantage; between the genuine maxims of an honest and magnanimous policy and the solid rewards of public prosperity and felicity; … the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained.” President Lincoln would quote the Gospel saying much the same thing “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” In other words, just as a national government has certain powers because of the nature of the thing so, too, is it the case that nations must, by nature, behave in certain ways if they wish to flourish and prosper. That being the case, it is fitting that we, the American people, pause at periodic intervals and give thanks to the being who Created us, and who, in Washington’s words, we hope will “grant unto all mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as He alone knows to be best.” Happy Thanksgiving.

from https://ift.tt/2OXUcEJ

from https://eliaandponto1.tumblr.com/post/180602793022

0 notes

Text

A National Thanksgiving: President Washington and America’s National Holiday

Editor’s note: This originally appeared on Thanksgiving Day, 2014.

Thanksgiving is a peculiar holiday, at least in the modern world. Its roots are religious, and the American nation is, at least in law, secular. Its very name speaks of thanks, or gratitude, and gratitude is an ancient virtue. Indeed Aristotle speaks highly of it. Even so, or perhaps for that reason, it is very American. In his Thanksgiving address in 1922, President Coolidge called it “perhaps the most characteristic of our national observances.” He was not wrong for, as Chesterton wrote, America is “a nation with the soul of a church,” and Abraham Lincoln called us an “almost chosen people.”

The holiday reminds us, in other words, of the peculiar character of the American nation, and of the President’s role in it. Strictly speaking, to be an American is to be an American citizen. When one calls someone an American, the first definition one usually has in mind is political. By contrast, when one says that someone is Chinese or Turkish, the first thought is of an ethnic or racial identity. Even so, there is an American culture. Hence it is very common to say that something is “very American.” Thanksgiving itself deserves that moniker. Is it a constitutional observance? That’s an open question.

In this holiday we see how the peculiar character of the Presidency compliments our exceptional nationality. Constitutionally speaking, the President is merely the American CEO. His job is to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” and in his oath, he swears to “execute the office of the President” and pledges to “preserve, protect and defend the constitution of the United States.” The oath says nothing about the American “nation.” Indeed the word “nation” does not appear in the Constitution, except in Article I, Section 8 when discussing relations with “foreign nations” and the “law of nations.” Strictly speaking, the President’s job is to put into effect the laws that Congress passes and to defend the “supreme law of the land.” Even so, the President is, in fact, head of state, and the leader of the American people. It is no surprise that the American president has, in time, acquired the trappings of a monarch—think of the entourage he travels with, the way he’s treated at the State of the Union address, the language with which we discuss the “White House’ and its parts, such as the “West Wing.” And a monarch is more than a CEO. He is the leader of the nation, in the classical sense of the nation.

George Washington set the tone for the office in many ways, none more so than in his Thanksgiving Proclamation, given in October, 1789, seven months after he took the oath of office. Why have such a proclamation at all? Where in Article I, Section 8 (the section that lists the powers the people gave the federal government) is the power to proclaim a federal holiday? In 1791 James Madison would criticize Alexander Hamilton’s assertion that the U.S. government has the authority to create a national bank, for nowhere in the Constitution did the people give the federal government the right to create a bank or to create a corporation (an entity that had traditionally been regarded as a “person” in the eyes of the law). And fourteen years later, the Louisiana Purchase would tie President Jefferson in knots, for nowhere did the people give the U.S. government the right to acquire territory. Yet Madison lost the national bank argument in 1791 and by 1816 he had changed his mind about its constitutionality. Meanwhile, Jefferson didn’t stop the Senate from ratifying the Louisiana Purchase. In other words, he and Madison implicitly accepted that there are some powers that belong to government due to the nature of the thing, and when the people created the U.S. government they, of necessity, allowed it those powers without which no government can function.

The authority to proclaim a Thanksgiving might seem trivial to us—mere words, and an idle declaration. But it is, in fact, fraught with meaning, for the assumption of such authority highlights the degree to which a President is, by nature, much like a monarch—albeit an elected one. Similarly, it points us to the limits of secular nationalism.

Consider President Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamation. He begins with the universal “duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favor.” But then he stops, as if he knew some might ask why the President is involved. Washington goes on, “Whereas both Houses of Congress have, by their joint committee, requested me ‘to recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a a form of government for their safety and happiness.’” Congress asked Washington to proclaim the day. An interesting request. Congress did not pass a law proclaiming a day of Thanksgiving. Such an act may, according to some constructions of the Constitution, have crossed over into an establishment of religion. Instead, they have merely asked the President to “recommend” such an observance to the people. But if it’s not a law, wherefore does the authority come from? It must adhere in the nature of the thing.

What is the power of a Presidential “recommendation”? Quite a bit, actually. And that is because the President is, as a practical matter, a national father figure. Those of us who are theoretically minded may fuss and fume that there is nothing in the Constitution suggesting such a role, and it is certainly true that there are many Americans who do not see it that way. It is nonetheless true that the President has always had such authority for a significant portion of the country. Even those who object to a particular President or his policies are often reacting as an unhappy child. And that is why a Presidential “recommendation” even of a merely ceremonial sort (I am not referring to the modern practice of the President or his minions “recommending” to businesses or Universities that they adopt certain practices. There is no implicit Presidential “or else” in this kind of proclamation) is simply the nature of the thing. A few states tried operating without a unitary executive in the years after 1776. The experiment was a failure. By the early 1790s, even Pennsylvania gave up on the effort. And once there is such an executive for the nation as a whole, he becomes “his elective majesty” even if we Americans are loathe to admit it.

That is what is so significant about the opening line of Washington’s Proclamation. He speaks of the “duty of all nations.” Such a declaration implies that nations are all alike in some ways. No nation is or can be exceptional in that regard. A nation, by nature, is a being in a moral universe. In the middle of the Thanksgiving Proclamation, Washington points back to the Declaration of Independence, noting that Americans are grateful “for the peaceable and rational manner in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness.” Americans should be grateful for the American experiment, the effort to show that men are capable of creating governments based upon “reflection and choice” as the first Federalist puts it. Even nations with governments under constitutions that are delegations of powers by the people cannot change the nature of the thing. And that means that national morality is a fundamental concern. At the start of the Defence of the Constitutions John Adams would link the two: “The people of America have now the best opportunity and the greatest trust in their hands, that Providence ever committed to so small a number since the transgression of the first pair. If they betray their trust, their guilt will merit even greater punishment than other nations have suffered, and the indignation of heaven.”

As Washington noted in his First inaugural Address, nations and individuals alike are judged by a common standard. The Universe being moral, nations that stink with injustice will, almost invariably inevitably (the ways of the Almighty being mysterious) suffer, just as individuals who do evil are punished, “since there is no truth more thoroughly established than that there exists in the economy and course of nature an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness; between duty and advantage; between the genuine maxims of an honest and magnanimous policy and the solid rewards of public prosperity and felicity; . . . the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained.” President Lincoln would quote the Gospel saying much the same thing “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” In other words, just as a national government has certain powers because of the nature of the thing so, too, is it the case that nations must, by nature, behave in certain ways if they wish to flourish and prosper. That being the case, it is fitting that we, the American people, pause at periodic intervals and give thanks to the being who Created us, and who, in Washington’s words, we hope will “grant unto all mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as He alone knows to be best.” Happy Thanksgiving.

from https://ift.tt/2OXUcEJ

0 notes

Text

A National Thanksgiving: President Washington and America’s National Holiday

Editor’s note: This originally appeared on Thanksgiving Day, 2014.

Thanksgiving is a peculiar holiday, at least in the modern world. Its roots are religious, and the American nation is, at least in law, secular. Its very name speaks of thanks, or gratitude, and gratitude is an ancient virtue. Indeed Aristotle speaks highly of it. Even so, or perhaps for that reason, it is very American. In his Thanksgiving address in 1922, President Coolidge called it “perhaps the most characteristic of our national observances.” He was not wrong for, as Chesterton wrote, America is “a nation with the soul of a church,” and Abraham Lincoln called us an “almost chosen people.”

The holiday reminds us, in other words, of the peculiar character of the American nation, and of the President’s role in it. Strictly speaking, to be an American is to be an American citizen. When one calls someone an American, the first definition one usually has in mind is political. By contrast, when one says that someone is Chinese or Turkish, the first thought is of an ethnic or racial identity. Even so, there is an American culture. Hence it is very common to say that something is “very American.” Thanksgiving itself deserves that moniker. Is it a constitutional observance? That’s an open question.

In this holiday we see how the peculiar character of the Presidency compliments our exceptional nationality. Constitutionally speaking, the President is merely the American CEO. His job is to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” and in his oath, he swears to “execute the office of the President” and pledges to “preserve, protect and defend the constitution of the United States.” The oath says nothing about the American “nation.” Indeed the word “nation” does not appear in the Constitution, except in Article I, Section 8 when discussing relations with “foreign nations” and the “law of nations.” Strictly speaking, the President’s job is to put into effect the laws that Congress passes and to defend the “supreme law of the land.” Even so, the President is, in fact, head of state, and the leader of the American people. It is no surprise that the American president has, in time, acquired the trappings of a monarch—think of the entourage he travels with, the way he’s treated at the State of the Union address, the language with which we discuss the “White House’ and its parts, such as the “West Wing.” And a monarch is more than a CEO. He is the leader of the nation, in the classical sense of the nation.

George Washington set the tone for the office in many ways, none more so than in his Thanksgiving Proclamation, given in October, 1789, seven months after he took the oath of office. Why have such a proclamation at all? Where in Article I, Section 8 (the section that lists the powers the people gave the federal government) is the power to proclaim a federal holiday? In 1791 James Madison would criticize Alexander Hamilton’s assertion that the U.S. government has the authority to create a national bank, for nowhere in the Constitution did the people give the federal government the right to create a bank or to create a corporation (an entity that had traditionally been regarded as a “person” in the eyes of the law). And fourteen years later, the Louisiana Purchase would tie President Jefferson in knots, for nowhere did the people give the U.S. government the right to acquire territory. Yet Madison lost the national bank argument in 1791 and by 1816 he had changed his mind about its constitutionality. Meanwhile, Jefferson didn’t stop the Senate from ratifying the Louisiana Purchase. In other words, he and Madison implicitly accepted that there are some powers that belong to government due to the nature of the thing, and when the people created the U.S. government they, of necessity, allowed it those powers without which no government can function.

The authority to proclaim a Thanksgiving might seem trivial to us—mere words, and an idle declaration. But it is, in fact, fraught with meaning, for the assumption of such authority highlights the degree to which a President is, by nature, much like a monarch—albeit an elected one. Similarly, it points us to the limits of secular nationalism.

Consider President Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamation. He begins with the universal “duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favor.” But then he stops, as if he knew some might ask why the President is involved. Washington goes on, “Whereas both Houses of Congress have, by their joint committee, requested me ‘to recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a a form of government for their safety and happiness.’” Congress asked Washington to proclaim the day. An interesting request. Congress did not pass a law proclaiming a day of Thanksgiving. Such an act may, according to some constructions of the Constitution, have crossed over into an establishment of religion. Instead, they have merely asked the President to “recommend” such an observance to the people. But if it’s not a law, wherefore does the authority come from? It must adhere in the nature of the thing.

What is the power of a Presidential “recommendation”? Quite a bit, actually. And that is because the President is, as a practical matter, a national father figure. Those of us who are theoretically minded may fuss and fume that there is nothing in the Constitution suggesting such a role, and it is certainly true that there are many Americans who do not see it that way. It is nonetheless true that the President has always had such authority for a significant portion of the country. Even those who object to a particular President or his policies are often reacting as an unhappy child. And that is why a Presidential “recommendation” even of a merely ceremonial sort (I am not referring to the modern practice of the President or his minions “recommending” to businesses or Universities that they adopt certain practices. There is no implicit Presidential “or else” in this kind of proclamation) is simply the nature of the thing. A few states tried operating without a unitary executive in the years after 1776. The experiment was a failure. By the early 1790s, even Pennsylvania gave up on the effort. And once there is such an executive for the nation as a whole, he becomes “his elective majesty” even if we Americans are loathe to admit it.

That is what is so significant about the opening line of Washington’s Proclamation. He speaks of the “duty of all nations.” Such a declaration implies that nations are all alike in some ways. No nation is or can be exceptional in that regard. A nation, by nature, is a being in a moral universe. In the middle of the Thanksgiving Proclamation, Washington points back to the Declaration of Independence, noting that Americans are grateful “for the peaceable and rational manner in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness.” Americans should be grateful for the American experiment, the effort to show that men are capable of creating governments based upon “reflection and choice” as the first Federalist puts it. Even nations with governments under constitutions that are delegations of powers by the people cannot change the nature of the thing. And that means that national morality is a fundamental concern. At the start of the Defence of the Constitutions John Adams would link the two: “The people of America have now the best opportunity and the greatest trust in their hands, that Providence ever committed to so small a number since the transgression of the first pair. If they betray their trust, their guilt will merit even greater punishment than other nations have suffered, and the indignation of heaven.”

As Washington noted in his First inaugural Address, nations and individuals alike are judged by a common standard. The Universe being moral, nations that stink with injustice will, almost invariably inevitably (the ways of the Almighty being mysterious) suffer, just as individuals who do evil are punished, “since there is no truth more thoroughly established than that there exists in the economy and course of nature an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness; between duty and advantage; between the genuine maxims of an honest and magnanimous policy and the solid rewards of public prosperity and felicity; . . . the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained.” President Lincoln would quote the Gospel saying much the same thing “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” In other words, just as a national government has certain powers because of the nature of the thing so, too, is it the case that nations must, by nature, behave in certain ways if they wish to flourish and prosper. That being the case, it is fitting that we, the American people, pause at periodic intervals and give thanks to the being who Created us, and who, in Washington’s words, we hope will “grant unto all mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as He alone knows to be best.” Happy Thanksgiving.

A National Thanksgiving: President Washington and America’s National Holiday syndicated from https://immigrationattorneyto.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

NATURALLY ANTI-SOCIAL?

The last posting of this blog got into the development of a fetus during gestation. This posting picks up the idea of development, but after birth. That posting was concerned with abortion rights, this one is about something else. It is concerned with the question: what determines behavior, nature or nurture? This last question has been the topic of many a discussion or argument. This posting relies on the reporting of a conservative pundit, Jonah Goldberg.[1] This blogger finds Goldberg’s take on this matter intriguing.

Today, the consensus has discredited John Locke’s view that humans are born with a blank slate. According to Locke, all behaviors, thinking, and even feelings are/were the product of experiences a person, beginning as an infant, experiences. Those experiences have their effect and either at a conscious or subconscious level they make their mark within one’s thinking. How one behaves, thinks, and feels reflects the cumulative effect of those experiences.

Goldberg reports that this view has been discarded by all serious students of human psychology. Instead, he points out that the consensus is that people through their biology are born with certain internal messaging and dispositions. He analogizes this by using the image of an app. A lot of what people encounter can be congruent with the content of that app or it can challenge what the app informs or leads the person to believe or feel. So, the question becomes: can a person override what the app leads people to believe or feel?

While the app can’t be replaced, add-ons can be acquired. That is, nurture – e.g., how a person is brought up by his/her parents or guardians – can affect the disposition of a person and that can lead to beliefs and feelings that would not be believed or felt without those experiences. Having made that concession, though, there are limits. Some built-in programming cannot be replaced. It might be tweaked, softened, redirected, but it cannot be dismissed or dashed by that parenting or what other “learning” efforts provide.

The content of the app is so enmeshed in what makes people human. So, what are the attributes of a person’s psychic app? One, Goldberg reports, is that babies are preprogrammed to have a moral sense. Six-month-old babies already bestow a character trait on puppets that are shown to be helpful or detrimental to another puppet trying to accomplish a simple task. They ascribe to those puppets who are helpful as “nice” and those who hamper the other puppet as “mean.” They further indicate they prefer the nice puppet.

This finding is further supported by other studies that indicate a person is born with a basic sense to being empathetic, altruistic, cooperative, and other moral predilections. But how those initial biases develop depends on the experiences the baby and then child encounters. One category of such experiences can be attributed to the culture in which a baby finds him/herself during those early months and years.

Another programmed indication is shown early on; a baby demonstrates preferences in the language he/she primarily hears – even before he/she knows how to speak or understand what is being said. That is, he/she is naturally drawn to pick up the sound of the prevailing language minutes after being born. That is, the fetus, in the womb, already seems to “hear” and “appreciate” the rhythm and pace of the language being spoken by his/her mother and those people with whom she converses.

In addition to voices and language, the infant demonstrates intense interest in facial appearances. Surely, being able to identify mother and other relatives can be, under certain dangerous situations, lifesaving. This sensitivity is more pronounced than the child’s ability to verbalize any differences he/she perceives. What seems to strongly affect these abilities is familiarity with images that are similar. “Who out there is like me and my mother and my father,” etc. seems to be important.

And for Goldberg’s concern, this element of the app – the bias for unity and familiarity – seems central. Why? Because, in Goldberg’s conservative bent, it helps bolster conservative assumptions. It does this in more than one way. For one, it bolsters the unifying role markets play in a world where people are naturally disposed to avoid or otherwise shun those who are different – the Other.

Yes, one can be naturally suspicious of unfamiliar, dissimilar people, but one wants to sell or lease him/her something like labor, a car, a service, etc. A market – by its role in allowing a people to make a living – encourages people to come together and deal with each other despite their natural aversions to the “Other” – those who are different.

But there is another function conservatives seem to accept. Goldberg writes:

Children and adults are constantly told that one needs to be taught to hate. This is laudable nonsense. We are, in a very real sense, born to hate every bit as much as we are born to love. The task of parents, schools, society, and civilization isn’t to teach us not to hate any more than it is to teach us not to love. The role of all of these institutions is to teach what we should or should not hate.[2]

He further states that until recently racism has been an accepted belief bias. It was not considered as evil, but natural. Goldberg uses this bit of evidence to support the notion that it is natural – not desired – and that one needs to count on society – culture, laws, taught notions of evil – to instill a more prudent view of race – one that proves to be more conducive to societal advancement. That is, racism is bad and counterproductive to the general good.

He also points out that all political ideologies – humans seem to naturally devise these belief systems – have their Others. That goes for capitalism, socialism, communism, conservatism, and even contemporary liberalism – this last group disparages evangelical Christians. They all hate someone or someone-s to some degree.

This writer finds Goldberg to offer a set of ideas that a federalist needs to think about seriously. If federalism is based on humans being able to come together to form a polity under a set of values that support community, collaboration, equality, and even liberty, then he/she cannot ignore any truths, if any, Goldberg points out.

To begin with, given what Goldberg argues, one can see how early versions of federalism were parochial. This blog has claimed that that was the case all the way back to the nation’s colonial past. Truly, while America held federalism as dominant, one can readily see how parochial it was. And that’s despite the onslaught of varied ethnicities that found their way to American shores. It further explains slavery, mistreatment of the latest immigrant group, and the inhuman treatment of the indigenous peoples.

While this treatment of the Other still plagues current American politics and social relations, at least there now exists a language that more honestly reflects those realities. The polity has enacted meaningful policies to address those biases, but much needs to be done. A civics program guided by a liberated federalism would be immensely helpful. But, if one can accept Goldberg’s claims about the Other, such instruction needs consider what those claims indicate.

[1] Jonah Goldberg, Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Populism, Nationalism, and Identity Politics Is Destroying American Democracy (New York, NY: Crown Forum, 2018).

[2] Ibid., 24 (Kindle edition).

0 notes

Text

A National Thanksgiving: President Washington and America’s National Holiday

Editor’s note: This originally appeared on Thanksgiving Day, 2014.

Thanksgiving is a peculiar holiday, at least in the modern world. Its roots are religious, and the American nation is, at least in law, secular. Its very name speaks of thanks, or gratitude, and gratitude is an ancient virtue. Indeed Aristotle speaks highly of it. Even so, or perhaps for that reason, it is very American. In his Thanksgiving address in 1922, President Coolidge called it “perhaps the most characteristic of our national observances.” He was not wrong for, as Chesterton wrote, America is “a nation with the soul of a church,” and Abraham Lincoln called us an “almost chosen people.”

The holiday reminds us, in other words, of the peculiar character of the American nation, and of the President’s role in it. Strictly speaking, to be an American is to be an American citizen. When one calls someone an American, the first definition one usually has in mind is political. By contrast, when one says that someone is Chinese or Turkish, the first thought is of an ethnic or racial identity. Even so, there is an American culture. Hence it is very common to say that something is “very American.” Thanksgiving itself deserves that moniker. Is it a constitutional observance? That’s an open question.

In this holiday we see how the peculiar character of the Presidency compliments our exceptional nationality. Constitutionally speaking, the President is merely the American CEO. His job is to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” and in his oath, he swears to “execute the office of the President” and pledges to “preserve, protect and defend the constitution of the United States.” The oath says nothing about the American “nation.” Indeed the word “nation” does not appear in the Constitution, except in Article I, Section 8 when discussing relations with “foreign nations” and the “law of nations.” Strictly speaking, the President’s job is to put into effect the laws that Congress passes and to defend the “supreme law of the land.” Even so, the President is, in fact, head of state, and the leader of the American people. It is no surprise that the American president has, in time, acquired the trappings of a monarch—think of the entourage he travels with, the way he’s treated at the State of the Union address, the language with which we discuss the “White House’ and its parts, such as the “West Wing.” And a monarch is more than a CEO. He is the leader of the nation, in the classical sense of the nation.

George Washington set the tone for the office in many ways, none more so than in his Thanksgiving Proclamation, given in October, 1789, seven months after he took the oath of office. Why have such a proclamation at all? Where in Article I, Section 8 (the section that lists the powers the people gave the federal government) is the power to proclaim a federal holiday? In 1791 James Madison would criticize Alexander Hamilton’s assertion that the U.S. government has the authority to create a national bank, for nowhere in the Constitution did the people give the federal government the right to create a bank or to create a corporation (an entity that had traditionally been regarded as a “person” in the eyes of the law). And fourteen years later, the Louisiana Purchase would tie President Jefferson in knots, for nowhere did the people give the U.S. government the right to acquire territory. Yet Madison lost the national bank argument in 1791 and by 1816 he had changed his mind about its constitutionality. Meanwhile, Jefferson didn’t stop the Senate from ratifying the Louisiana Purchase. In other words, he and Madison implicitly accepted that there are some powers that belong to government due to the nature of the thing, and when the people created the U.S. government they, of necessity, allowed it those powers without which no government can function.

The authority to proclaim a Thanksgiving might seem trivial to us—mere words, and an idle declaration. But it is, in fact, fraught with meaning, for the assumption of such authority highlights the degree to which a President is, by nature, much like a monarch—albeit an elected one. Similarly, it points us to the limits of secular nationalism.

Consider President Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamation. He begins with the universal “duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favor.” But then he stops, as if he knew some might ask why the President is involved. Washington goes on, “Whereas both Houses of Congress have, by their joint committee, requested me ‘to recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a a form of government for their safety and happiness.’” Congress asked Washington to proclaim the day. An interesting request. Congress did not pass a law proclaiming a day of Thanksgiving. Such an act may, according to some constructions of the Constitution, have crossed over into an establishment of religion. Instead, they have merely asked the President to “recommend” such an observance to the people. But if it’s not a law, wherefore does the authority come from? It must adhere in the nature of the thing.

What is the power of a Presidential “recommendation”? Quite a bit, actually. And that is because the President is, as a practical matter, a national father figure. Those of us who are theoretically minded may fuss and fume that there is nothing in the Constitution suggesting such a role, and it is certainly true that there are many Americans who do not see it that way. It is nonetheless true that the President has always had such authority for a significant portion of the country. Even those who object to a particular President or his policies are often reacting as an unhappy child. And that is why a Presidential “recommendation” even of a merely ceremonial sort (I am not referring to the modern practice of the President or his minions “recommending” to businesses or Universities that they adopt certain practices. There is no implicit Presidential “or else” in this kind of proclamation) is simply the nature of the thing. A few states tried operating without a unitary executive in the years after 1776. The experiment was a failure. By the early 1790s, even Pennsylvania gave up on the effort. And once there is such an executive for the nation as a whole, he becomes “his elective majesty” even if we Americans are loathe to admit it.

That is what is so significant about the opening line of Washington’s Proclamation. He speaks of the “duty of all nations.” Such a declaration implies that nations are all alike in some ways. No nation is or can be exceptional in that regard. A nation, by nature, is a being in a moral universe. In the middle of the Thanksgiving Proclamation, Washington points back to the Declaration of Independence, noting that Americans are grateful “for the peaceable and rational manner in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness.” Americans should be grateful for the American experiment, the effort to show that men are capable of creating governments based upon “reflection and choice” as the first Federalist puts it. Even nations with governments under constitutions that are delegations of powers by the people cannot change the nature of the thing. And that means that national morality is a fundamental concern. At the start of the Defence of the Constitutions John Adams would link the two: “The people of America have now the best opportunity and the greatest trust in their hands, that Providence ever committed to so small a number since the transgression of the first pair. If they betray their trust, their guilt will merit even greater punishment than other nations have suffered, and the indignation of heaven.”

As Washington noted in his First inaugural Address, nations and individuals alike are judged by a common standard. The Universe being moral, nations that stink with injustice will, almost invariably inevitably (the ways of the Almighty being mysterious) suffer, just as individuals who do evil are punished, “since there is no truth more thoroughly established than that there exists in the economy and course of nature an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness; between duty and advantage; between the genuine maxims of an honest and magnanimous policy and the solid rewards of public prosperity and felicity; . . . the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained.” President Lincoln would quote the Gospel saying much the same thing “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” In other words, just as a national government has certain powers because of the nature of the thing so, too, is it the case that nations must, by nature, behave in certain ways if they wish to flourish and prosper. That being the case, it is fitting that we, the American people, pause at periodic intervals and give thanks to the being who Created us, and who, in Washington’s words, we hope will “grant unto all mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as He alone knows to be best.” Happy Thanksgiving.

from https://ift.tt/2OXUcEJ

0 notes

Text

A National Thanksgiving: President Washington and America’s National Holiday

Editor’s note: This originally appeared on Thanksgiving Day, 2014.

Thanksgiving is a peculiar holiday, at least in the modern world. Its roots are religious, and the American nation is, at least in law, secular. Its very name speaks of thanks, or gratitude, and gratitude is an ancient virtue. Indeed Aristotle speaks highly of it. Even so, or perhaps for that reason, it is very American. In his Thanksgiving address in 1922, President Coolidge called it “perhaps the most characteristic of our national observances.” He was not wrong for, as Chesterton wrote, America is “a nation with the soul of a church,” and Abraham Lincoln called us an “almost chosen people.”

The holiday reminds us, in other words, of the peculiar character of the American nation, and of the President’s role in it. Strictly speaking, to be an American is to be an American citizen. When one calls someone an American, the first definition one usually has in mind is political. By contrast, when one says that someone is Chinese or Turkish, the first thought is of an ethnic or racial identity. Even so, there is an American culture. Hence it is very common to say that something is “very American.” Thanksgiving itself deserves that moniker. Is it a constitutional observance? That’s an open question.

In this holiday we see how the peculiar character of the Presidency compliments our exceptional nationality. Constitutionally speaking, the President is merely the American CEO. His job is to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” and in his oath, he swears to “execute the office of the President” and pledges to “preserve, protect and defend the constitution of the United States.” The oath says nothing about the American “nation.” Indeed the word “nation” does not appear in the Constitution, except in Article I, Section 8 when discussing relations with “foreign nations” and the “law of nations.” Strictly speaking, the President’s job is to put into effect the laws that Congress passes and to defend the “supreme law of the land.” Even so, the President is, in fact, head of state, and the leader of the American people. It is no surprise that the American president has, in time, acquired the trappings of a monarch—think of the entourage he travels with, the way he’s treated at the State of the Union address, the language with which we discuss the “White House’ and its parts, such as the “West Wing.” And a monarch is more than a CEO. He is the leader of the nation, in the classical sense of the nation.

George Washington set the tone for the office in many ways, none more so than in his Thanksgiving Proclamation, given in October, 1789, seven months after he took the oath of office. Why have such a proclamation at all? Where in Article I, Section 8 (the section that lists the powers the people gave the federal government) is the power to proclaim a federal holiday? In 1791 James Madison would criticize Alexander Hamilton’s assertion that the U.S. government has the authority to create a national bank, for nowhere in the Constitution did the people give the federal government the right to create a bank or to create a corporation (an entity that had traditionally been regarded as a “person” in the eyes of the law). And fourteen years later, the Louisiana Purchase would tie President Jefferson in knots, for nowhere did the people give the U.S. government the right to acquire territory. Yet Madison lost the national bank argument in 1791 and by 1816 he had changed his mind about its constitutionality. Meanwhile, Jefferson didn’t stop the Senate from ratifying the Louisiana Purchase. In other words, he and Madison implicitly accepted that there are some powers that belong to government due to the nature of the thing, and when the people created the U.S. government they, of necessity, allowed it those powers without which no government can function.

The authority to proclaim a Thanksgiving might seem trivial to us—mere words, and an idle declaration. But it is, in fact, fraught with meaning, for the assumption of such authority highlights the degree to which a President is, by nature, much like a monarch—albeit an elected one. Similarly, it points us to the limits of secular nationalism.