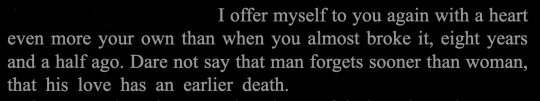

#and how shiv is pushed on by the ghost of her father

Text

And they both drown...

Sources: Persuasion - Jane Austen, Eurydice - HD, Umbrella Academy)

#succession#shiv roy#tom wombsgans#tomshiv#succession spoilers#Hiiii#never done one of these before#sorry if its shit#the quotes are a bit random but i like them#i wish i knew more gut wrenching female rage poems#i wish i could have included a dido reference#omg the parallels of duty versus love and agency in suicide#and how shiv is pushed on by the ghost of her father#leaving behind tom who was on a path to power#but she has upstaged and undermined him#UGH#and the company is rome of course#web weaving

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

If at all helpful and/or encouraging, I cannot express how excited I am to read your post-succession fic. You're one of my favorite succession writers and I am waiting with baited breath for this fic :)

Ah! It is, anon! Thank you so, so much. You can have a little snippet if you like - the whole fic's set across two days about two weeks after the finale, so kinda keeping up with the rhythm of the last season, haha.

-

Roman texts her again that night, not a cartoon this time at least but a comment about Connor and Willa being back in New Mexico for a few days. Finally putting the old commune on the market, should I buy it? Always thought I’d make a good cult leader, and the place has great bones. Real Waco meets Burning Man potential, hey on a related note, you heard from Kendall since you 🔪

Shiv blinks, types how the fuck is that a related note?

Adds: and maybe don’t put your cult plans in writing or you’ll be done before you even start.

Dipshit.

The typing ellipsis appears on the screen, but Shiv doesn’t wait for him to reply. She has a shower, dries her hair, tells the chef she feels like lamb instead of chicken for dinner and ignores Rosaline’s barely concealed look of annoyance at the late instruction. Whatever. Shiv folds back onto the couch to read the barrage of messages Roman’s sent back in the meantime.

Hmm, good advice, you’re in the cult! A high-level position in the inner sanctum. You can do whatever Gerri’s job was.

Unless you think I stand a chance of swaying Gerri…

Pretend I didn’t send that, text withdrawn, you saw nothing, if you ever bring this up you’ll be out of the cult etc etc etc

And re: K – I’ve heard rumours he’s 🍳

Shiv frowns at the little saucepan emoji. Cooking?

She pastes it into Google, but all she gets is hot pansexual which is definitely not what Roman means, and she’s about to send a question mark back when the door opens and Tom steps through.

The air shifts like it always seems to these days, like it has maybe since he made CEO, since he chose her father over her, or maybe even earlier, maybe since he started flirting with a prison stint. It doesn’t chill, like, god, what a fucking cliché that would be, but it feels - - tighter almost. A spring pushed down, like the weight of them is too heavy for the moment. She swallows, slides her phone into to the pocket of her pants and sits up straight.

“Hey,” she says, and suddenly she realises Tom’s holding more than just his usual shit from work. In his hands is a box, which he lowers carefully to the dining room table as he pivots back to look at her on the couch.

“Hey,” he replies, and he looks almost surprised to see her here, or underprepared for her, maybe. Something. An oddly cautious expression on his often oddly cautious face, and it makes her stand up. Makes her close the distance between them, eyes first on him, then the box on the table.

“Good day at the office?”

“Sure. Matsson was in, but you already knew that.”

Shiv hums, offering nothing of her meeting with him, and glimpses instead the top of a frame in the box.

“What’s this?”

Somewhere behind them, she can hear Rosaline in the kitchen, the fzzt of the gas stove top and the whir of the oven, can hear the thrum of the central heating and feel it soft as a gloved hand on the side of her cheek, but none of it matters when she sees the first photograph in full.

Her father and Reagan, shoulder to shoulder, hand in short, fat fingered hand.

She glances back up at Tom, her face carefully blank.

“They’re from your dad’s office,” he tells her, like she didn’t know, shrugging out of his blazer and dropping it to the back of one of the chairs. Leaving it for Tilda to put away later. “I - - it’s been suggested that I move in fairly quickly, just for the. You know. The optics.”

“Oh, sure, clear out the ghosts.”

“Something like that. Marks a transition, I guess.”

Shiv sniffs, can’t help it, thumbs through the photos of her father with heads of state and right-leaning leaders. A few cultural figures, a few musicians. Morrissey and Johnny Cash. Something in her twists in a way it feels it shouldn't.

“Roman knows a guy,” she says, shooting for flippant. “Some sort of business shaman, if you want the place smudged.”

“I’ll keep that in mind,” Tom replies. His hand finds the edge of the box, the opposite side to where Shiv’s are, curling tentatively against the cardboard. “Most of it's been packed up now, but I just thought you might want these? Or your brothers might. Since they were obviously important to him.”

There’s something earnest to his tone, saccharine and soft, and she wonders if he means it, but in the same breath, she thinks these are worthless and he knows it. Only worth as much as the frames, the glass, the paper they’re printed on – all of them are otherwise online. Digitised in the family archive. The helmets, the medals, the war memorabilia, those are the only things with value.

She wonders if he’s kept them.

“I kept the photo of you.”

Which - -

Shiv blinks.

“You kept my father’s photo of me,” she echoes, and Tom must hear something in it, because he takes his hands from the edge of the box, shakes his head.

“It’s just a photo, Shiv. A nice photo.”

“Of me.”

“Of you.”

The one Matsson had his hands on in the office before he made clear she’d be fuckable to him again after she’s had this thing. A photo of her from before she and Tom even met, one where her hair was long and her face still round and soft with the last flush of her adolescence, even though she was in her twenties by then. She can even remember when it was taken – a father’s day photoshoot with her and him for Vogue, a spread and a story about the beautiful, promising daughters of hard, powerful men. Dad had had every photo from it printed, hell, she’d even kept a few herself, but Tom keeping it, Matsson holding it - -

The thought sinks somewhere deep in her, and she tucks her hair behind her ear, pushes the frames back in the box until the one of her father and Reagan faces up again, and somewhere beside her, Tom shifts his weight.

“He didn’t have any pictures of your brothers in there, you know. Guess you were the favourite.”

It’s something, she knows, an offering maybe more genuine than the photos, but all she can think is what does that matter? Where the fuck has it ever gotten her?

She turns, offers him a flat smile, and Tom gives one back.

#there's actually not that much tom in this fic (although he kind of haunts it a little)#but all four sibs'll be there bullying each other into surviving <3#but yes haha#thank you again anon!#this was a lovely ask to get#succession fic#welcome to my ama

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

the wells family

affluent tech fam

sometimes your siblings are all you have and that still rings true for the wells siblings. the wells are a funky little group. they grew up in manhattan, new york..or los angeles, or dallas, texas. point is, they've grown up every where but nyc is their home base. their father is the ceo of a tech conglomerate and pushed his kids 100% to be as cut throat as him. how annie still retained her optimistic personality is a mystery. but her father would always kick his kids just to watch them come back. their mother wasn't that great either and all but became a ghost in their lives.

after a car accident that took someone's life and the rest of her siblings going through their own issues, annie decided to move on. she was effectively bought out of her shares and squirreled away the money (a lot of money) and moved to los angeles where she eventually got married and has an eight year old son and went low contact with her entire family. now! her older brother has called her back for whatever reason and now she's back with a husband and son in tow that she has literally kept hidden from them! so yay for family drama!

the siblings are pretty open, especially if they're half siblings which is a possibility so i'm super flexible with faces as long as they look like they could be related to mara lafontan? just run them by me! anyways, they're pretty much all bicker with each other and annie is definitely the black sheep of the bunch but despite the sniping they really do love each other. if you need to reach me you can always get at me through my discord shiv roy#2155

--- wells // oldest brother // 35-37 // played by ???

--- wells // middle brother // 32-34 // played by ???

annie wells leander // only sister // 31 // played by reese

--- wells // youngest brother // 29-27 // played by ???

1 note

·

View note

Text

5

I left everybody and went home to rest. My aunt said I was wasting my time hanging around with Dean and his gang. I knew that was wrong, too. Life is life, and kind is kind. What I wanted was to take one more magnificent trip to the West Coast and get back in time for the spring semester in school. And what a trip it turned out to be! I only went along for the ride, and to see what else Dean was going to do, and finally, also, knowing Dean would go back to Camille in Frisco, I wanted to have an affair with Marylou. We got ready to cross the groaning continent again. I drew my GI check and gave Dean eighteen dollars to mail to his wife; she was waiting for him to come home and she was broke. What was on Marylou's mind I don't know. Ed Dunkel, as ever, just followed.

There were long, funny days spent in Carlo's apartment before we left. He went around in his bathrobe and made semi-ironical speeches: "Now I'm not trying to take your hincty sweets from you, but it seems to me the time has come to decide what you are and what you're going to do." Carlo was working as typist in an office. "I want to know what all this sitting around the house all day is intended to mean. What all this talk is and what you propose to do. Dean, why did you leave Camille and pick up Marylou?" No answer-giggles. "Marylou, why are you traveling around the country like this and what are your womanly intentions concerning the shroud?" Same answer. "Ed Dunkel, why did you abandon your new wife in Tucson and what are you doing here sitting on your big fat ass? Where's your home? What's your job?" Ed Dunkel bowed his head in genuine befuddlement. "Sal -how comes it you've fallen on such sloppy days and what have you done with Lucille?" He adjusted his bathrobe and sat facing us all. "The days of wrath are yet to come. The balloon won't sustain you much longer. And not only that, but it's an abstract balloon. You'll all go flying to the West Coast and come staggering back in search of your stone."

In these days Carlo had developed a tone of voice which he hoped sounded like what he called The Voice of Rock; the whole idea was to stun people into the realization of the rock. "You pin a dragon to your hats," he warned us; "you're up in the attic with the bats." His mad eyes glittered at us. Since the Dakar Doldrums he had gone through a terrible period which he called the Holy Doldrums, or Harlem Doldrums, when he lived in Harlem in midsummer and at night woke up in his lonely room and heard "the great machine" descending from the sky; and when he walked on 12 5th Street "under water" with all the other fish. It was a riot of radiant ideas that had come to enlighten his brain. He made Marylou sit on his lap and commanded her to subside. He told Dean, "Why don't you just sit down and relax? Why do you jump around so much?" Dean ran around, putting sugar in his coffee and saying, "Yes! Yes! Yes!" At night Ed Dunkel slept on the floor on cushions, Dean and Marylou pushed Carlo out of bed, and Carlo sat up in the kitchen over his kidney stew, mumbling the predictions of the rock. I came in days and watched everything.

Ed Dunkel said to me, "Last night I walked clear down to Times Square and just as I arrived I suddenly realized I was a ghost-it was my ghost walking on the sidewalk." He said these things to me without comment, nodding his head emphatically. Ten hours later, in the midst of someone else's conversation, Ed said, "Yep, it was my ghost walking on the sidewalk."

Suddenly Dean leaned to me earnestly and said, "Sal, I have something to ask of you-very important to me-I wonder how you'll take it-we're buddies, aren't we?"

"Sure are, Dean." He almost blushed. Finally he came out with it: he wanted me to work Marylou. I didn't ask him why because I knew he wanted to see what Marylou was like with another man. We were sitting in Ritzy's Bar when he proposed the idea; we'd spent an hour walking Times Square, looking for Hassel. Ritzy's Bar is the hoodlum bar of the streets around Times Square; it changes names every year. You walk in there and you don't see a single girl, even in the booths, just a great mob of young men dressed in all varieties of hoodlum cloth, from red shirts to zoot suits. It is also the hustlers' bar -the boys who make a living among the sad old homos of the Eighth Avenue night. Dean walked in there with his eyes slitted to see every single face. There were wild Negro queers, sullen guys with guns, shiv-packing seamen, thin, noncommittal junkies, and an occasional well-dressed middle-aged detective, posing as a bookie and hanging around half for interest and half for duty. It was the typical place for Dean to put down his request. All kinds of evil plans are hatched in Ritzy's Bar-you can sense it in the air-and all kinds of mad sexual routines are initiated to go with them. The safecracker proposes not only a certain loft on 14th Street to the hoodlum, but that they sleep together. Kinsey spent a lot of time in Ritzy's Bar, interviewing some of the boys; I was there the night his assistant came, in 1945. Hassel and Carlo were interviewed.

Dean and I drove back to the pad and found Marylou in bed. Dunkel was roaming his ghost around New York. Dean told her what we had decided. She said she was pleased. I wasn't so sure myself. I had to prove that I'd go through with it. The-bed had been the deathbed of a big man and sagged in the middle. Marylou lay there, with Dean and myself on each side of her, poised on the upjutting mattress-ends, not knowing what to say. I said, "Ah hell, I can't do this."

"Go on, man, you promised!" said Dean.

"What about Marylou?" I said. "Come on, Marylou, what do you think?"

"Go ahead," she said.

She embraced me and I tried to forget old Dean was there. Every time I realized he was there in the dark, listening for every sound, I couldn't do anything but laugh. It was horrible.

"We must all relax," said Dean.

"I'm afraid I can't make it. Why don't you go in the kitchen a minute?"

Dean did so. Marylou was so lovely, but I whispered, "Wait until we be lovers in San Francisco; my heart isn't in it." I was right, she could tell. It was three children of the earth trying to decide something in the night and having all the weight of past centuries ballooning in the dark before them. There was a strange quiet in the apartment. I went and tapped Dean and told him to go to Marylou; and I retired to the couch. I could hear Dean, blissful and blabbering and frantically rocking. Only a guy who's spent five years in jail can go to such maniacal helpless extremes; beseeching at the portals of the soft source, mad with a completely physical realization of the origins of life-bliss; blindly seeking to return the way he came. This is the result of years looking at sexy pictures behind bars; looking at the legs and breasts of women in popular magazines; evaluating the hardness of the steel halls and the softness of the woman who is not there. Prison is where you promise yourself the right to live. Dean had never seen his mother's face. Every new girl, every new wife, every new child was an addition to his bleak impoverishment. Where was his father?-old bum Dean Moriarty the Tinsmith, riding freights, working as a scullion in railroad cookshacks, stumbling, down-crashing in wino alley nights, expiring on coal piles, dropping his yellowed teeth one by one in the gutters of the West. Dean had every right to die the sweet deaths of complete love of his Marylou-1 didn't want to interfere, I just wanted to follow.

Carlo came back at dawn and put on his bathrobe. He wasn't sleeping any more those days. "Ech!" he screamed. He was going out of his mind from the confusion of jam on the floor, pants, dresses thrown around, cigarette butts, dirty dishes, open books-it was a great forum we were having. Every day the world groaned to turn and we were making our appalling studies of the night. Marylou was black and blue from a fight with Dean about something; his face was scratched. It was time to go.

We drove to my house, a whole gang of ten, to get my bag and call Old Bull Lee in New Orleans from the phone in the bar where Dean and I had our first talk years ago when he came to my door to learn to write. We heard Bull's whining voice eighteen hundred miles away. "Say, what do you boys expect me to do with this Galatea Dunkel? She's been here two weeks now, hiding in her room and refusing to talk to either Jane or me. Have you got this character Ed Dunkel with you? For krissakes bring him down and get rid of her. She's sleeping in our best bedroom and's run clear out of money. This ain't a hotel." He assured Bull with whoops and cries over the phone-there was Dean, Marylou, Carlo, Dunkel, me, Ian MacArthur, his wife, Tom Saybrook, God knows who else, all yelling and drinking beer over the phone at befuddled Bull, who above all things hated confusion. "Well," he said, "maybe you'll make better sense when you gets down here if you gets down here." I said good-by to my aunt and promised to be back in two weeks and took off for California again.

6

It was drizzling and mysterious at the beginning of our journey. I could see that it was all going to be one big saga of the mist. "Whooee!" yelled Dean. "Here we go!" And he hunched over the wheel and gunned her; he was back in his element, everybody could see that. We were all delighted, we all realized we were leaving confusion and nonsense behind and performing our one and noble function of the time, move.

And we moved! We flashed past the mysterious white signs in the night somewhere in New Jersey that say SOUTH (with an arrow) and WEST (with an arrow) and took the south one. New Orleans! It burned in our brains. From the dirty snows of "frosty fagtown New York," as Dean called it, all the way to the greeneries and river smells of old New Orleans at the washed-out bottom of America; then west. Ed was in the back seat; Marylou and Dean and I sat in front and had the warmest talk about the goodness and joy of life. Dean suddenly became tender. "Now dammit, look here, all of you, we all must admit that everything is fine and there's no need in the world to worry, and in fact we should realize what it would mean to us to UNDERSTAND that we're not REALLY worried about ANYTHING. Am I right?" We all agreed. "Here we go, we're all together . . . What did we do in New York? Let's forgive." We all had our spats back there. "That's behind us, merely by miles and inclinations. Now we're heading down to New Orleans to dig Old Bull Lee and ain't that going to be kicks and listen will you to this old tenorman blow his top"-he shot up the radio volume till the car shuddered-"and listen to him tell the story and put down true relaxation and knowledge."

We all jumped to the music and agreed. The purity of the road. The white line in the middle of the highway unrolled and hugged our left front tire as if glued to our groove. Dean hunched his muscular neck, T-shirted in the winter night, and blasted the car along. He insisted I drive through Baltimore for traffic practice; that was all right, except he and Marylou insisted on steering while they kissed and fooled around. It was crazy; the radio was on full blast. Dean beat drums on the dashboard till a great sag developed in it; I did too. The poor Hudson-the slow boat to China-was receiving her beating.

"Oh man, what kicks!" yelled Dean. "Now Marylou, listen really, honey, you know that I'm hotrock capable of everything at the same time and I have unlimited energy-now in San Francisco we must go on living together. I know just the place for you-at the end of the regular chain-gang run-I'll be home just a cut-hair less than every two days and for twelve hours at a stretch, and man, you know what we can do in twelve hours, darling. Meanwhile I'll go right on living at Camille's like nothin, see, she won't know. We can work it, we've done it before." It was all right with Marylou, she was really out for Camille's scalp. The understanding had been that Marylou would switch to me in Frisco, but I now began to see they were going to stick and I was going to be left alone on my butt at the other end of the continent. But why think about that when all the golden land's ahead of you and all kinds of unforeseen events wait lurking to surprise you and make you glad you're alive to see?

We arrived in Washington at dawn. It was the day of Harry Truman's inauguration for his second term. Great displays of war might were lined along Pennsylvania Avenue as we rolled by in our battered boat. There were 6-295, PT boats, artillery, all kinds of war material that looked murderous in the snowy grass; the last thing was a regular small ordinary lifeboat that looked pitiful and foolish. Dean slowed down to look at it. He kept shaking his head in awe. "What are these people up to? Harry's sleeping somewhere in this town. . . . Good old Harry. . . . Man from Missouri, as I am. . . . That must be his own boat."

Dean went to sleep in the back seat and Dunkel drove. We gave him specific instructions to take it easy. No sooner were we snoring than he gunned the car up to eighty, bad bearings and all, and not only that but he made a triple pass at a spot where a cop was arguing with a motorist-he was in the fourth lane of a four-lane highway, going the wrong way. Naturally the cop took after us with his siren whining. We were stopped. He told us to follow him to the station house. There was a mean cop in there who took an immediate dislike to Dean; he could smell jail all over him. He sent his cohort outdoors to question Marylou and me privately. They wanted to know how old Marylou was, they were trying to whip up a Mann Act idea. But she had her marriage certificate. Then they took me aside alone and wanted to know who was sleeping with Marylou. "Her husband," I said quite simply. They were curious. Something was fishy. They tried some amateur Sherlocking by asking the same questions twice, expecting us to make a slip. I said, "Those two fellows are going back to work on the railroad in California, this is the short one's wife, and I'm a friend on a two-week vacation from college."

The cop smiled and said, "Yeah? Is this really your own wallet?"

Finally the mean one inside fined Dean twenty-five dollars. We told them we only had forty to go all the way to the Coast; they said that made no difference to them. When Dean protested, the mean cop threatened to take him back to Pennsylvania and slap a special charge on him.

"What charge?"

"Never mind what charge. Don't worry about that, wiseguy."

We had to give them the twenty-five. But first Ed Dunkel, that culprit, offered to go to jail. Dean considered it. The cop was infuriated; he said, "If you let your partner go to jail I'm taking you back to Pennsylvania right now. You hear that?" All we wanted to do was go. "Another speeding ticket in Virginia and you lose your car," said the mean cop as a parting volley. Dean was red in the face. We drove off silently. It was just like an invitation to steal to take our trip-money away from us. They knew we were broke and had no relatives on the road or to wire to for money. The American police are involved in psychological warfare against those Americans who don't frighten them with imposing papers and threats. It's a Victorian police force; it peers out of musty windows and wants to inquire about everything, and can make crimes if the crimes don't exist to its satisfaction. "Nine lines of crime, one of boredom," said Louis-Ferdinand Celine. Dean was so mad he wanted to come back to Virginia and shoot the cop as soon as he had a gun.

"Pennsylvania!" he scoffed. "I wish I knew what that charge was! Vag, probably; take all my money and charge me vag. Those guys have it so damn easy. They'll out and shoot you if you complain, too." There was nothing to do but get happy with ourselves again and forget about it. When we got through Richmond we began forgetting about it, and soon everything was okay.

Now we had fifteen dollars to go all the way. We'd have to pick up hitchhikers and bum quarters off them for gas. In the Virginia wilderness suddenly we saw a man walking on the road. Dean zoomed to a stop. I looked back and said he was only a bum and probably didn't have a cent.

"We'll just pick him up for kicks!" Dean laughed. The man was a ragged, bespectacled mad type, walking along reading a paperbacked muddy book he'd found in a culvert by the road. He got in the car and went right on reading; he was incredibly filthy and covered with scabs. He said his name was Hyman Solomon and that he walked all over the USA, knocking and sometimes kicking at Jewish doors and demanding money: "Give me money to eat, I am a Jew."

He said it worked very well and that it was coming to him. We asked him what he was reading. He didn't know. He didn't bother to look at the title page. He was only looking at the words, as though he had found the real Torah where it belonged, in the wilderness.

"See? See? See?" cackled Dean, poking my ribs. "I told you it was kicks. Everybody's kicks, man!" We carried Solomon all the way to Testament. My brother by now was in his new house on the other side of town. Here we were back on the long, bleak street with the railroad track running down the middle and the sad, sullen Southerners loping in front of hardware stores and five-and-tens.

Solomon said, "I see you people need a little money to continue your journey. You wait for me and I'll go hustle up a few dollars at a Jewish home and I'll go along with you as far as Alabama." Dean was all beside himself with happiness; he and I rushed off to buy bread and cheese spread for a lunch in the car. Marylou and Ed waited in the car. We spent two hours in Testament waiting for Hyman Solomon to show up; he was hustling for his bread somewhere in town, but we couldn't see him. The sun began to grow red and late.

Solomon never showed up so we roared out of Testament. "Now you see, Sal, God does exist, because we keep getting hung-up with this town, no matter what we try to do, and you'll notice the strange Biblical name of it, and that strange Biblical character who made us stop here once more, and all things tied together all over like rain connecting everybody the world over by chain touch. . . ." Dean rattled on like this; he was overjoyed and exuberant. He and I suddenly saw the whole country like an oyster for us to open; and the pearl was there, the pearl was there. Off we roared south. We picked up another hitchhiker. This was a sad young kid who said he had an aunt who owned a grocery store in Dunn, North Carolina, right outside Fayetteville. "When we get there can you bum a buck off her? Right! Fine! Let's go!" We were in Dunn in an hour, at dusk. We drove to where the kid said his aunt had the grocery store. It was a sad little street that dead-ended at a factory wall. There was a grocery store but there was no aunt. We wondered what the kid was talking about. We asked him how far he was going; he didn't know. It was a big hoax; once upon a time, in some lost back-alley adventure, he had seen the grocery store in Dunn, and it was the first story that popped into his disordered, feverish mind. We bought him a hot dog, but Dean said we couldn't take him along because we needed room to sleep and room for hitchhikers who could buy a little gas. This was sad but true. We left him in Dunn at nightfall.

I drove through South Carolina and beyond Macon, Georgia, as Dean, Marylou, and Ed slept. All alone in the night I had my own thoughts and held the car to the white line in the holy road. What was I doing? Where was I going? I'd soon find out. I got dog-tired beyond Macon and woke up Dean to resume. We got out of the car for air and suddenly both of us were stoned with joy to realize that in the darkness all around us was fragrant green grass and the smell of fresh manure and warm waters. "We're in the South! We've left the winter!" Faint daybreak illuminated green shoots by the side of the road. I took a deep breath; a locomotive howled across-the darkness, Mobile-bound. So were we. I took off my shirt and exulted. Ten miles down the road Dean drove into a filling-station with the motor off, noticed that the attendant was fast asleep at the desk, jumped out, quietly filled the gas tank, saw to it the bell didn't ring, and rolled off like an Arab with a five-dollar tankful of gas for our pilgrimage.

I slept and woke up to the crazy exultant sounds of music and Dean and Marylou talking and the great green land rolling by. "Where are we?"

"Just passed the tip of Florida, man-Flomaton, it's called." Florida! We were rolling down to the coastal plain and Mobile; up ahead were great soaring clouds of the Gulf of Mexico. It was only thirty-two hours since we'd said good-by to everybody in the dirty snows of the North. We stopped at a gas station, and there Dean and Marylou played piggyback around the tanks and Dunkel went inside and stole three packs of cigarettes without trying. We were fresh out. Rolling into Mobile over the long tidal highway, we all took our winter clothes off and enjoyed the Southern temperature. This was when Dean started telling his life story and when, beyond Mobile, he came upon an obstruction of wrangling cars at a crossroads and instead of slipping around them just balled right through the driveway of a gas station and went right on without relaxing his steady continental seventy. We left gaping faces behind us. He went right on with his tale. "I tell you it's true, I started at nine, with a girl called Milly Mayfair in back of Rod's garage on Grant Street-same street Carlo lived on in Denver. That's when my father was still working at the smithy's a bit. I remember my aunt yelling out the window, 'What are you doing down there in back of the garage?' Oh honey Marylou, if I'd only known you then! Wow! How sweet you musta been at nine." He tittered maniacally; he stuck his finger in her mouth and licked it; he took her hand and rubbed it over himself. She just sat there, smiling serenely.

Big long Ed Dunkel sat looking out the window, talking to himself. "Yes sir, I thought I was a ghost that night." He was also wondering what Galatea Dunkel would say to him in New Orleans.

Dean went on. "One time I rode a freight from New Mexico clear to LA-I was eleven years old, lost my father at a siding, we were all in a hobo jungle, I was with a man called Big Red, my father was out drunk in a boxcar-it started to roll-Big Red and I missed it-I didn't see my father for months. I rode a long freight all the way to California, really flying, first-class freight, a desert Zipper. All the way I rode over the couplings-you can imagine how dangerous, I was only a kid, I didn't know-clutching a loaf of bread under one arm and the other hooked around the brake bar. This is no story, this is true. When I got to LA I was so starved for milk and cream I got a job in a dairy and the first thing I did I drank two quarts of heavy cream and puked."

"Poor Dean," said Marylou, and she kissed him. He stared ahead proudly. He loved her.

We were suddenly driving along the blue waters of the Gulf, and at the same time a momentous mad thing began on the radio; it was the Chicken Jazz'n Gumbo disk-jockey show from New Orleans, all mad jazz records, colored records, with the disk jockey saying, "Don't worry 'bout nothing!" We saw New Orleans in the night ahead of us with joy. Dean rubbed his hands over the wheel. "Now we're going to get our kicks!" At dusk we were coming into the humming streets of New Orleans. "Oh, smell the people!" yelled Dean with his face out the window, sniffing. "Ah! God! Life!" He swung around a trolley. "Yes!" He darted the car and looked in every direction for girls. "Look at her!" The air was so sweet in New Orleans it seemed to come in soft bandannas; and you could smell the river and really smell the people, and mud, and molasses, and every kind of tropical exhalation with your nose suddenly removed from the dry ices of a Northern winter. We bounced in our seats. "And dig her!" yelled Dean, pointing at another woman. "Oh, I love, love, love women! I think women are wonderful! I love women!" He spat out the window; he groaned; he clutched his head. Great beads of sweat fell from his forehead from pure excitement and exhaustion.

We bounced the car up on the Algiers ferry and found ourselves crossing the Mississippi River by boat. "Now we must all get out and dig the river and the people and smell the world," said Dean, bustling with his sunglasses and cigarettes and leaping out of the car like a jack-in-the-box. We followed.

On rails we leaned and looked at the great brown father of waters rolling down from mid-America like the torrent of broken souls-bearing Montana logs and Dakota muds and Iowa vales and things that had drowned in Three Forks, where the secret began in ice. Smoky New Orleans receded on one side; old, sleepy Algiers with its warped woodsides bumped us on the other. Negroes were working in the hot afternoon, stoking the ferry furnaces that burned red and made our tires smell. Dean dug them, hopping up and down in the heat. He rushed around the deck and upstairs with his baggy pants hanging halfway down his belly. Suddenly I saw him eagering on the flying bridge. I expected him to take off on wings. I heard his mad laugh all over the boat-"Hee-hee-hee-hee-hee!" Marylou was with him. He covered everything in a jiffy, came back with the full story, jumped in the car just as everybody was tooting to go, and we slipped off, passing two or three cars in a narrow space, and found ourselves darting through Algiers.

"Where? Where?" Dean was yelling.

We decided first to clean up at a gas station and inquire for Bull's whereabouts. Little children were playing in the drowsy river sunset; girls were going by with bandannas and cotton blouses and bare legs. Dean ran up the street to see everything. He looked around; he nodded; he rubbed his belly. Big Ed sat back in the car with his hat over his eyes, smiling at Dean. I sat on the fender. Marylou was in the women's John. From bushy shores where infinitesimal men fished with sticks, and from delta sleeps that stretched up along the reddening land, the big humpbacked river with its mainstream leaping came coiling around Algiers like a snake, with a nameless rumble. Drowsy, peninsular Algiers with all her bees and shanties was like to be washed away someday. The sun slanted, bugs flip-flopped, the awful waters groaned.

We went to Old Bull Lee's house outside town near the river levee. It was on a road that ran across a swampy field. The house was a dilapidated old heap with sagging porches running around and weeping willows in the yard; the grass was a yard high, old fences leaned, old barns collapsed. There was no one in sight. We pulled right into the yard and saw washtubs on the back porch. I got out and went to the screen door. Jane Lee was standing in it with her eyes cupped toward the sun. "Jane," I said. "It's me. It's us."

She knew that. "Yes, I know. Bull isn't here now. Isn't that a fire or something over there?" We both looked toward the sun.

"You mean the sun?"

"Of course I don't mean the sun-I heard sirens that way. Don't you know a peculiar glow?" It was toward New Orleans; the clouds were strange.

"I don't see anything," I said.

Jane snuffed down her nose. "Same old Paradise."

That was the way we greeted each other after four years; Jane used to live with my wife and me in New York. "And is Galatea Dunkel here?" I asked. Jane was still looking for her fire; in those days she ate three tubes of benzedrine paper a day. Her face, once plump and Germanic and pretty, had become stony and red and gaunt. She had caught polio in New Orleans and limped a little. Sheepishly Dean and the gang came out of the car and more or less made themselves at home. Galatea Dunkel came out of her stately retirement in the back of the house to meet her tormentor. Galatea was a serious girl. She was pale and looked like tears all over. Big Ed passed his hand through his hair and said hello. She looked at him steadily.

"Where have you been? Why did you do this to me?" And she gave Dean a dirty look; she knew the score. Dean paid absolutely no attention; what he wanted now was food; he asked Jane if there was anything. The confusion began right there.

Poor Bull came home in his Texas Chevy and found his house invaded by maniacs; but he greeted me with a nice warmth I hadn't seen in him for a long time. He had bought this house in New Orleans with some money he had made growing black-eyed peas in Texas with an old college schoolmate whose father, a mad-paretic, had died and left a fortune. Bull himself only got fifty dollars a week from his own family, which wasn't too bad except that he spent almost that much per week on his drug habit-and his wife was also expensive, gobbling up about ten dollars' worth of benny tubes a week. Their food bill was the lowest in the country; they hardly ever ate; nor did the children-they didn't seem to care. They had two wonderful children: Dodie, eight years old; and little Ray, one year. Ray ran around stark naked in the yard, a little blond child of the rainbow. Bull called him "the Little Beast," after W. C. Fields. Bull came driving into the yard and unrolled himself from the car bone by bone, and came over wearily, wearing glasses, felt hat, shabby suit, long, lean, strange, and laconic, saying, "Why, Sal, you finally got here; let's go in the house and have a drink."

It would take all night to tell about Old Bull Lee; let's just say now, he was a teacher, and it may be said that he had every right to teach because he spent all his time learning; and the things he learned were what he considered to be and called "the facts of life," which he learned not only out of necessity but because he wanted to. He dragged his long, thin body around the entire United States and most of Europe and North Africa in his time, only to see what was going on; he married a White Russian countess in Yugoslavia to get her away from the Nazis in the thirties; there are pictures of him with the international cocaine set of the thirties-gangs with wild hair, leaning on one another; there are other pictures of him in a Panama hat, surveying the streets of Algiers; he never saw the White Russian countess again. He was an exterminator in Chicago, a bartender in New York, a summons-server in Newark. In Paris he sat at cafe tables, watching the sullen French faces go by. In Athens he looked up from his ouzo at what he called the ugliest people in the world. In Istanbul he threaded his "way through crowds of opium addicts and rug-sellers, looking for the facts. In English hotels he read Spengler and the Marquis de Sade. In Chicago he planned to hold up a Turkish bath, hesitated just for two minutes too long for a drink, and wound up with two dollars and had to make a run for it. He did all these things merely for the experience. Now the final study was the drug habit. He was now in New Orleans, slipping along the streets with shady characters and haunting connection bars.

There is a strange story about his college days that illustrates something else about him: he had friends for cocktails in his well-appointed rooms one afternoon when suddenly his pet ferret rushed out and bit an elegant teacup queer on the ankle and everybody hightailed it out the door, screaming. Old Bull leaped up and grabbed his shotgun and said, "He smells that old rat again," and shot a hole in the wall big enough for fifty rats. On the wall hung a picture of an ugly old Cape Cod house. His friends said, "Why do you have that ugly thing hanging there?" and Bull said, "I like it because it's ugly." All his life was in that line. Once I knocked on his door in the 60th Street slums of New York and he opened it wearing a derby hat, a vest with nothing underneath, and long striped sharpster pants; in his hands he had a cookpot, birdseed in the pot, and was trying to mash the seed to roll in cigarettes. He also experimented in boiling codeine cough syrup down to a black mash - that didn't work too well. He spent long hours with Shakespeare - the "Immortal Bard," he called him - on his lap. In New Orleans he had begun to spend long hours with the Mayan Codices on his lap, and, although he went on talking, the book lay open all the time. I said once, "What's going to happen to us when we die?" and he said, "When you die you're just dead, that's all." He had a set of chains in his room that he said he used with his psychoanalyst; they were experimenting with narcoanalysis and found that Old Bull had seven separate personalities, each growing worse and worse on the way down, till finally he was a raving idiot and had to be restrained with chains. The top personality was an English lord, the bottom the idiot. Halfway he was an old Negro who stood in line, waiting with everyone else, and said, "Some's bastards, some's ain't, that's the score."

Bull had a sentimental streak about the old days m America, especially 1910, when you could get morphine in a drugstore without prescription and Chinese smoked opium in their evening windows and the country was wild and brawling and free, with abundance and any kind of freedom for everyone. His chief hate was Washington bureaucracy; second to that, liberals; then cops. He spent all his time talking and teaching others. Jane sat at his feet; so did I; so did Dean; and so had Carlo Marx. We'd all learned from him. He was a gray, nondescript-looking fellow you wouldn't notice on the street, unless you looked closer and saw his mad, bony skull with its strange youthfulness-a Kansas minister with exotic, phenomenal fires and mysteries. He had studied medicine in Vienna; had studied anthropology, read everything; and now he was settling to his life's work, which was the study of things them-selves.-in the streets of life and the night. He sat in his chair; Jane brought drinks, martinis. The shades by his chair were always drawn, day and night; it was his corner of the house. On his lap were the Mayan Codices and an air gun which he occasionally raised to pop benzedrine tubes across the room. I kept rushing around, putting up new ones. We all took shots and meanwhile we talked. Bull was curious to know the reason for this trip. He peered at us and snuffed down his nose, thfump, like a sound in a dry tank.

"Now, Dean, I want you to sit quiet a minute and tell me what you're doing crossing the country like this."

Dean could only blush and say, "Ah well, you know how it is."

"Sal, what are you going to the Coast for?" "Only for a few days. I'm coming back to school." "What's the score with this Ed Dunkel? What kind of character is he?" At that moment Ed was making up to Galatea in the bedroom; it didn't take him long. We didn't know what to tell Bull about Ed Dunkel. Seeing that we didn't know anything about ourselves, he whipped out three sticks of tea and said to go ahead, supper'd be ready soon.

"Ain't nothing better in the world to give you an appetite. I once ate a horrible lunchcart hamburg on tea and it seemed like the most delicious thing in the world. I just got back from Houston last week, went to see Dale about our black-eyed peas. I was sleeping in a motel one morning when all of a sudden I was blasted out of bed. This damn fool had just shot his wife in the room next to mine. Everybody stood around confused, and the guy just got in his car and drove off, left the shotgun on the floor for the sheriff. They finally caught him in Houma, drunk as a lord. Man ain't safe going around this country any more without a gun." He pulled back his coat and showed us his revolver. Then he opened the drawer and showed us the rest of his arsenal. In New York he once had a sub-machine-gun under his bed. "I got something better than that now - a German Scheintoth gas gun; look at this beauty, only got one shell. I could knock out a hundred men with this gun and have plenty of time to make a getaway. Only thing wrong, I only got one shell."

"I hope I'm not around when you try it," said Jane from the kitchen. "How do you know it's a gas shell?" Bull snuffed; he never paid any attention to her sallies but he heard them. His relation with his wife was one of the strangest: they talked till late at night; Bull liked to hold the floor, he went right on in his dreary monotonous voice, she tried to break in, she never could; at dawn he got tired and then Jane talked and he listened, snuffing and going thfump down his nose. She loved that man madly, but in a delirious way of some kind; there was never any mooching and mincing around, just talk and a very deep companionship that none of us would ever be able to fathom. Something curiously unsympathetic and cold between them was really a form of humor by which they communicated their own set of subtle vibrations. Love is all; Jane was never more than ten feet away from Bull and never missed a word he said, and he spoke in a very low voice, too.

Dean and I were yelling about a big night in New Orleans and wanted Bull to show us around. He threw a damper on this. "New Orleans is a very dull town. It's against the law to go to the colored section. The bars are insufferably dreary."

I said, "There must be some ideal bars in town."

"The ideal bar doesn't exist in America. An ideal bar is something that's gone beyond our ken. In nineteen ten a bar was a place where men went to meet during or after work, and all there was was a long counter, brass rails, spittoons, player piano for music, a few mirrors, and barrels of whisky at ten cents a shot together with barrels of beer at five cents a mug. Now all you get is chromium, drunken women, fags, hostile bartenders, anxious owners who hover around the door, worried about their leather seats and the law; just a lot of screaming at the wrong time and deadly silence when a stranger walks in."

We argued about bars. "All right," he said, "I'll take you to New Orleans tonight and show you what I mean." And he deliberately took us to the dullest bars. We left Jane with the children; supper was over; she was reading the want ads of the New Orleans Times-Picayune. I asked her if she was looking for a job; she only said it was the most interesting part of the paper. Bull rode into town with us and went right on talking. "Take it easy, Dean, we'll get there, I hope; hup, there's the ferry, you don't have to drive us clear into the river." He held on. Dean had gotten worse, he confided in me. "He seems to me to be headed for his ideal fate, which is compulsive psychosis dashed with a jigger of psychopathic irresponsibility and violence." He looked at Dean out of the corner of his eye. "If you go to California with this madman you'll never make it. Why don't you stay in New Orleans with me? We'll play the horses over to Graetna and relax in my yard. I've got a nice set of knives and I'm building a target. Some pretty juicy dolls downtown, too, if that's in your line these days." He snuffed. We were on the ferry and Dean had leaped out to lean over the rail. I followed, but Bull sat on in the car, snuffing, thfump. There was a mystic wraith of fog over the brown waters that night, together with dark driftwoods; and across the way New Orleans glowed orange-bright, with a few dark ships at her hem, ghostly fogbound Cereno ships with Spanish balconies and ornamental poops, till you got up close and saw they were just old freighters from Sweden and Panama. The ferry fires glowed in the night; the same Negroes plied the shovel and sang. Old Big Slim Hazard had once worked on the Algiers ferry as a deckhand; this made me think of Mississippi Gene too; and as the river poured down from mid-America by starlight I knew, I knew like mad that everything I had ever known and would ever know was One. Strange to say, too, that night we crossed the ferry with Bull Lee a girl committed suicide off the deck; either just before or just after us; we saw it in the paper the next day.

We hit all the dull bars in the French Quarter with Old Bull and went back home at midnight. That night Marylou took everything in the books; she took tea, goofballs, benny, liquor, and even asked Old Bull for a shot of M, which of course he didn't give her; he did give her a martini. She was so saturated with elements of all kinds that she came to a standstill and stood goofy on the porch with me. It was a wonderful porch Bull had. It ran clear around the house; by moonlight with the willows it looked like an old Southern mansion that had seen better days. In the house Jane sat reading the want ads in the living room; Bull was in the bathroom taking his fix, clutching his old black necktie in his teeth for a tourniquet and jabbing with the needle into his woesome arm with the thousand holes; Ed Dunkel was sprawled out with Galatea in the massive master bed that Old Bull and Jane never used; Dean was rolling tea; and Marylou and I imitated Southern aristocracy.

"Why, Miss Lou, you look lovely and most fetching tonight."

"Why, thank you, Crawford, I sure do appreciate the nice things you do say."

Doors kept opening around the crooked porch, and members of our sad drama in the American night kept popping out to find out where everybody was. Finally I took a walk alone to the levee. I wanted to sit on the muddy bank and dig the Mississippi River; instead of that I had to look at it with my nose against a wire fence. When you start separating the people from their rivers what have you got? "Bureaucracy!" says Old Bull; he sits with Kafka on his lap, the lamp burns above him, he snuffs, thfump. His old house creaks. And the Montana log rolls by in the big black river of the night. " 'Tain't nothin but bureaucracy. And unions! Especially unions!" But dark laughter would come again.

7

It was there in the morning when I got up bright and early and found Old Bull and Dean in the back yard. Dean was wearing his gas-station coveralls and helping Bull. Bull had found a great big piece of thick rotten wood and was desperately yanking with a hammerhook at little nails imbedded in it. We stared at the nails; there were millions of them; they were like worms.

"When I get all these nails out of this I'm going to build me a shelf that'll last a thousand years!" said Bull, every bone shuddering with boyish excitement. "Why, Sal, do you realize the shelves they build these days crack under the weight of knickknacks after six months or generally collapse? Same with houses, same with clothes. These bastards have invented plastics by which they could make houses that last forever. And tires. Americans are killing themselves by the millions every year with defective rubber tires that get hot on the road and blow up. They could make tires that never blow up. Same with tooth powder. There's a certain gum they've invented and they won't show it to anybody that if you chew it as a kid you'll never get a cavity for the rest of your born days. Same with clothes. They can make clothes that last forever. They prefer making cheap goods so's everybody'll have to go on working and punching timeclocks and organizing themselves in sullen unions and floundering around while the big grab goes on in Washington and Moscow." He raised his big piece of rotten wood. "Don't you think this'll make a splendid shelf?"

It was early in the morning; his energy was at its peak. The poor fellow took so much junk into his system he could only weather the greater proportion of his day in that chair with the lamp burning at noon, but in the morning he was magnificent. We began throwing knives at the target. He said he'd seen an Arab in Tunis who could stick a man's eye from forty feet. This got him going on his aunt, who went to the Casbah in the thirties. "She was with a party of tourists led by a guide. She had a diamond ring on her little finger. She leaned on a wall to rest a minute and an Ay-rab rushed up and appropriated her ring finger before she could let out a cry, my dear. She suddenly realized she had no little finger. Hi-hi-hi-hi-hi!" When he laughed he compressed his lips together and made it come out from his belly, from far away, and doubled up to lean on his knees. He laughed a long time. "Hey Jane!" he yelled gleefully. "I was just telling Dean and Sal about my aunt in the Casbah!"

"I heard you," she said across the lovely warm Gulf morning from the kitchen door. Great beautiful clouds floated overhead, valley clouds that made you feel the vastness of old tumbledown holy America from mouth to mouth and tip to tip. All pep and juices was Bull. "Say, did I ever tell you about Dale's father? He was the funniest old man you ever saw in your life. He had paresis, which eats away the forepart of your brain and you get so's you're not responsible for anything that comes into your mind. He had a house in Texas and had carpenters working twenty-four hours a day putting on new wings. He'd leap up in the middle of the night and say, 'I don't want that goddam wing; put it over there.' The carpenters had to take everything down and start all over again. Come dawn you'd see them hammering away at the new wing. Then the old man'd get bored with that and say, 'Goddammit, I wanta go to Maine!' And he'd get into his car and drive off a hundred miles an hour-great showers of chicken feathers followed his track for hundreds of miles. He'd stop his car in the middle of a Texas town just to get out and buy some whisky. Traffic would honk all around him and he'd come rushing out of the store, yelling, 'Thet your goddam noith, you bunth of bathats!' He lisped; when you have paresis you lips, I mean you lisps. One night he came to my house in Cincinnati and tooted the horn and said, 'Come on out and let's go to Texas to see Dale.' He was going back from Maine. He claimed he bought a house-oh, we wrote a story about him at college, where you see this horrible shipwreck and people in the water clutching at the sides of the lifeboat, and the old man is there with a machete, hackin at their fingers. 'Get away, ya bunth a bathats, thith my cottham boath!' Oh, he was horrible. I could tell you stories about him all day. Say, ain't this a nice day?"

And it sure was. The softest breezes blew in from the levee; it was worth the whole trip. We went into the house after Bull to measure the wall for a shelf. He showed us the dining-room table he built. It was made of wood six inches thick. "This is a table that'll last a thousand years!" said Bull, leaning his long thin face at us maniacally. He banged on it.

In the evenings he sat at this table, picking at his food and throwing the bones to the cats. He had seven cats. "I love cats. I especially like the ones that squeal when I hold 'em over the bathtub." He insisted on demonstrating; someone was in the bathroom. "Well," he said, "we can't do that now. Say, I been having a fight with the neighbors next door." He told us about the neighbors; they were a vast crew with sassy children who threw stones over the rickety fence at Dodie and Ray and sometimes at Old Bull. He told them to cut it out; the old man rushed out and yelled something in Portuguese. Bull went in the house and came back with his shotgun, upon which he leaned demurely; the incredible simper on his face beneath the long hatbrim, his whole body writhing coyly and snakily as he waited, a grotesque, lank, lonely clown beneath the clouds. The sight of him the Portuguese must have thought something out of an old evil dream.

We scoured the yard for things to do. There was a tremendous fence Bull had been working on to separate him from the obnoxious neighbors; it would never be finished, the task was too much. He rocked it back and forth to show how solid it was. Suddenly he grew tired and quiet and went in the house and disappeared in the bathroom for his pre-lunch fix. He came out glassy-eyed and calm, and sat down under his burning lamp. The sunlight poked feebly behind the drawn shade. "Say, why don't you fellows try my orgone accumulator? Put some juice in your bones. I always rush up and take off ninety miles an hour for the nearest whorehouse, hor-hor-hor!" This was his "laugh" laugh-when he wasn't really laughing. The orgone accumulator is an ordinary box big enough for a man to sit inside on a chair: a layer of wood, a layer of metal, and another layer of wood gather in orgones from the atmosphere and hold them captive long enough for the human body to absorb more than a usual share. According to Reich, orgones are vibratory atmospheric atoms of the life-principle. People get cancer because they run out of orgones. Old Bull thought his orgone accumulator would be improved if the wood he used was as organic as possible, so he tied bushy bayou leaves and twigs to his mystical outhouse. It stood there in the hot, flat yard, an exfoliate machine clustered and bedecked with maniacal contrivances. Old Bull slipped off his clothes and went in to sit and moon over his navel. "Say, Sal, after lunch let's you and me go play the horses over to the bookie joint in Graetna." He was magnificent. He took a nap after lunch in his chair, the air gun on his lap and little Ray curled around his neck, sleeping. It was a pretty sight, father and son, a father who would certainly never bore his son when it came to finding things to do and talk about. He woke up with a start and stared at me. It took him a minute to recognize who I was. "What are you going to the Coast for, Sal?" he asked, and went back to sleep in a moment.

In the afternoon we went to Graetna, just Bull and me. We drove in his old Chevy. Dean's Hudson was low and sleek; Bull's Chevy was high and rattly. It was just like 1910. The bookie joint was located near the waterfront in a big chromium-leather bar that opened up in the back to a tremendous hall where entries and numbers were posted on the wall. Louisiana characters lounged around with Racing Forms. Bull and I had a beer, and casually Bull went over to the slot machine and threw a half-dollar piece in. The counters I clicked "Jackpot"-"Jackpot"-"Jackpot"-and the last

"Jackpot" hung for just a moment and slipped back to "Cherry." He had lost a hundred dollars or more just by a hair. "Damn!" yelled Bull. "They got these things adjusted. You could see it right then. I had the jackpot and the mechanism clicked it back. Well, what you gonna do." We examined the Racing Form. I hadn't played the horses in years and was bemused with all the new names. There was one horse called Big Pop that sent me into a temporary trance thinking of my father, who used to play the horses with me. I was just about to mention it to Old Bull when he said, "Well I think I'll try this Ebony Corsair here."

Then I finally said it. "Big Pop reminds me of my father."

He mused for just a second, his clear blue eyes fixed on mine hypnotically so that I couldn't tell what he was thinking or where he was. Then he went over and bet on Ebony Corsair. Big Pop won and paid fifty to one.

"Damn!" said Bull. "I should have known better, I've had experience with this before. Oh, when will we ever learn?"

"What do you mean?"

"Big Pop is what I mean. You had a vision, boy, a vision. Only damn fools pay no attention to visions. How do you know your father, who was an old horseplayer, just didn't momentarily communicate to you that Big Pop was going to win the race? The name brought the feeling up in you, he took advantage of the name to communicate. That's what I was thinking about when you mentioned it. My cousin in Missouri once bet on a horse that had a name that reminded him of his mother, and it won and paid a big price. The same thing happened this afternoon." He shook his head. "Ah, let's go. This is the last time I'll ever play the horses with you around; all these visions drive me to distraction." In the car as we drove back to his old house he said, "Mankind will someday realize that we are actually in contact with the dead and with the other world, whatever it is; right now we could predict, if we only exerted enough mental will, what is going to happen within the next hundred years and be able to take steps to avoid all kinds of catastrophes. When a man dies he undergoes a mutation in his brain that we know nothing about now but which will be very clear someday if scientists get on the ball. The bastards right now are only interested in seeing if they can blow up the world."

We told Jane about it. She sniffed. "It sounds silly to me." She plied the broom around the kitchen. Bull went in the bathroom for his afternoon fix.

Out on the road Dean and Ed Dunkel were playing basketball with Dodie's ball and a bucket nailed on a lamppost. I joined in. Then we turned 10 feats of athletic prowess. Dean completely amazed me. He had Ed and me hold a bar of iron up to our waists, and just standing there he popped right over it, holding his heels. "Go ahead, raise it." We kept raising it till it was chest-high. Still he jumped over it with ease. Then he tried the running broad jump and did at least twenty feet and more. Then I raced him down the road. I can do the hundred in 10:5. He passed me like the wind. As we ran I had a mad vision of Dean running through all of life just like that -his bony face outthrust to life, his arms pumping, his brow sweating, his legs twinkling like Groucho Marx, yelling, "Yes! Yes, man, you sure can go!" But nobody could go as fast as he could, and that's the truth. Then Bull came out with a couple of knives and started showing us how to disarm a would-be shiver in a dark alley. I for my part showed him a very good trick, which is falling on the ground in front of your adversary and gripping him with your ankles and flipping him over on his hands and grabbing his wrists in full nelson. He said it was pretty good. He demonstrated some jujitsu. Little Dodie called her mother to the porch and said, "Look at the silly men." She was such a cute sassy little thing that Dean couldn't take his eyes off her.

"Wow. Wait till she grows up! Can you see her cuttin down Canal Street with her cute eyes. Ah! Oh!" He hissed through his teeth.

We spent a mad day in downtown New Orleans walking around with the Dunkels. Dean was out of his mind that day. When he saw the T & NO freight trains in the yard he wanted to show me everything at once. "You'll be brakeman 'fore I'm through with ya!" He and I and Ed Dunkel ran across the tracks and hopped a freight at three individual points; Marylou and Galatea were waiting in the car. We rode the train a half-mile into the piers, waving at switchmen and flagmen. They showed me the proper way to get off a moving car; the back foot first and let the train go away from you and come around and place the other foot down. They showed me the refrigerator cars, the ice compartments, good for a ride on any winter night in a string of empties. "Remember what I told you about New Mexico to LA?" cried Dean. "This was the way I hung on . . ."

We got back to the girls an hour late and of course they were mad. Ed and Galatea had decided to get a room in New Orleans and stay there and work. This was okay with Bull, who was getting sick and tired of the whole mob. The invitation, originally, was for me to come alone. In the front room, where Dean and Marylou slept, there were jam and coffee stains and empty benny tubes all over the floor; what's more it was Bull's workroom and he couldn't get on with his shelves. Poor Jane was driven to distraction by the continual jumping and running around on the part of Dean. We were waiting for my next GI check to come through; my aunt was forwarding it. Then we were off, the three of us-Dean, Marylou, me. When the check came I realized I hated to leave Bull's wonderful house so suddenly, but Dean was all energies and ready to do.

In a sad red dusk we were finally seated in the car and Jane, Dodie, little boy Ray, Bull, Ed, and Galatea stood around in the high grass, smiling. It was good-by. At the last moment Dean and Bull had a misunderstanding over money; Dean had wanted to borrow; Bull said it was out of the question. The feeling reached back to Texas days. Con-man Dean was antagonizing people away from him by degrees. He giggled maniacally and didn't care; he rubbed his fly, stuck his finger in Marylou's dress, slurped up her knee, frothed at the mouth, and said, "Darling, you know and I know that everything is straight between us at last beyond the furthest abstract definition in metaphysical terms or any terms you want to specify or sweetly impose or harken back . . ." and so on, and zoom went the car and we were off again for California.

8

What is that feeling when you're driving away from people and they recede on the plain till you see their specks dispersing?-it's the too-huge world vaulting us, and it's good-by. But we lean forward to the next crazy venture beneath the skies.

We wheeled through the sultry old light of Algiers, back on the ferry, back toward the mud-splashed, crabbed old ships across the river, back on Canal, and out; on a two-lane highway to Baton Rouge in purple darkness; swung west there, crossed the Mississippi at a place called Port Alien. Port Alien-where the river's all rain and roses in a misty pinpoint darkness and where we swung around a circular drive in yellow foglight and suddenly saw the great black body below a , bridge and crossed eternity again. What is the Mississippi River?-a washed clod in the rainy night, a soft plopping ( from drooping Missouri banks, a dissolving, a riding of the tide down the eternal waterbed, a contribution to brown foams, a voyaging past endless vales and trees and levees, * down along, down along, by Memphis, Greenville, Eudora, Vicksburg, Natchez, Port Alien, and Port Orleans and Port of the Deltas, by Potash, Venice, and the Night's Great Gulf, and out.

With the radio on to a mystery program, and as I looked out the window and saw a sign that said USE COOPER'S PAINT and I said, "Okay, I will." we rolled across the hoodwink night of the Louisiana plains-Lawtell, Eunice, Kinder, and De Ouincy, western rickety towns becoming more bayou-like as \\e reached the Sabine. In Old Opelousas I went into a grocery store to buy bread and cheese while Dean saw to gas and oil. It was just a shack; I could hear the family eating supper in the back. I waited a minute; they went on talking. I took bread and cheese and slipped out the door. We had barely enough money to make Frisco. Meanwhile Dean took a cartoon of cigarettes from the gas station and we were stocked for the voyage-gas, oil, cigarettes, and food. Crooks don't know. He pointed the car straight down the road.

Somewhere near Starks we saw a great red glow in the sky ahead; we wondered what it was; in a moment we were passing it. It was a fire beyond the trees; there were many cars parked on the highway. It must have been some kind of fish-fry, and on the other hand it might have been anything. The country turned strange and dark near Deweyville. Suddenly we were in the swamps.

"Man, do you imagine what it would be like if we found a jazzjoint in these swamps, with great big black fellas moanin guitar blues and drinkin snakejuice and makin signs at us?"

"Yes!"

There were mysteries around here. The car was going over a dirt road elevated off the swamps that dropped on both sides and drooped with vines. We passed an apparition; it was a Negro man in a white shirt walking along with his arms up-spread to the inky firmament. He must have been praying or calling down a curse. We zoomed right by; I looked out the back window to see his white eyes. "Whoo!" said Dean. "Look out. We better not stop in this here country." At one point we got stuck at a crossroads and stopped the car anyway. Dean turned off the headlamps. We were surrounded by a great forest of viny trees in which we could almost hear the slither of a million copperheads. The only thing we could see was the red ampere button on the Hudson dashboard. Marylou squealed with fright. We began laughing maniac laughs to her. We were scared too. We wanted to get out of this mansion of the snake, this mireful drooping dark, and zoom on back to familiar American ground and cowtowns. There was a smell of oil and dead water in the air. This was a manuscript of the night we couldn't read. An owl hooted. We took a chance on one of the dirt roads, and pretty soon we were crossing the evil old Sabine River that is responsible for all these swamps. With amazement we saw great structures of light ahead of us. "Texas! It's Texas! Beaumont oil town!" Huge oil tanks and refineries loomed like cities in the oily fragrant air.

"I'm glad we got out of there," said Marylou. "Let's play some more mystery programs now."

We zoomed through Beaumont, over the Trinity River at Liberty, and straight for Houston. Now Dean got talking about his Houston days in 1947. "Hassel! That mad Hassel! I look for him everywhere I go and I never find him. He used to get us so hung-up in Texas here. We'd drive in with Bull for groceries and Hassel'd disappear. We'd have to go looking for him in every shooting gallery in town." We were entering Houston. "We had to look for him in this spade part of town most of the time. Man, he'd be blasting with every mad cat he could find. One night we lost him and took a hotel room. We were supposed to bring ice back to Jane because her food was rotting. It took us two days to find Hassel. I got hung-up myself-1 gunned shopping women in the afternoon, right here, downtown, supermarkets"-we flashed by in the empty night-"and found a real gone dumb girl who was out of her mind and just wandering, trying to steal an orange. She was from Wyoming. Her beautiful body was matched only by her idiot mind. I found her babbling and took her back to the room. Bull was drunk trying to get this young Mexican kid drunk. Carlo was writing poetry on heroin. Hassel didn't show up till midnight at the jeep. We found him sleeping in the back seat. The ice was all melted. Hassel said he took about five sleeping pills. Man, if my memory could only serve me right the way my mind works I could tell you every detail of the things we did. Ah, but we know time. Everything takes care of itself. I could close my eyes and this old car would take care of itself."

In the empty Houston streets of four o'clock in the morning a motorcycle kid suddenly roared through, all bespangled and bedecked with glittering buttons, visor, slick black jacket, a Texas poet of the night, girl gripped on his back like a papoose, hair flying, onward-going, singing, "Houston, Austin, Fort Worth, Dallas-and sometimes Kansas City-and sometimes old Antone, ah-haaaaa!" They pinpointed out of sight. "Wow! Dig that gone gal on his belt! Let's all blow!" Dean tried to catch up with them. "Now wouldn't it be fine if we could all get together and have a real going goofbang together with everybody sweet and fine and agreeable, no> hassles, no infant rise of protest or body woes misconceptalized or sumpin? Ah! but we know time." He bent to it and pushed the car.

Beyond Houston his energies, great as they were, gave out and I drove. Rain began to fall just as I took the wheel. Now we were on the great Texas plain and, as Dean said, "You drive and drive and you're still in Texas tomorrow night." The rain lashed down. I drove through a rickety little cowtown with a muddy main street and found myself in a dead end. "Hey, what do I do?" They were both asleep. I turned and crawled back through town. There wasn't a soul in sight and not a single light. Suddenly a horseman in a raincoat appeared in my headlamps. It was the sheriff. He had a ten-gallon hat, drooping in the torrent. "Which way to Austin?" He told me politely and I started off. Outside town I suddenly saw two headlamps flaring directly at me in the lashing rain, Whoops, I thought I was on the wrong side of the road; { eased right and found myself rolling in the mud; I rolled back to the road. Still the headlamps came straight for me. At the last moment I realized the other driver was on the wrong side of the road and didn't know it. I swerved at thirty into the mud; it was flat, no ditch, thank God. The offending car backed up in the downpour. Four sullen fieldworkers, snuck from their chores to brawl in drinking fields, all white shirts and dirty brown arms, sat looking at me dumbly in the night. The driver was as drunk as the lot.

He said, "Which way t'Houston?" I pointed my thumb back. I was thunderstruck in the middle of the thought that they had done this on purpose just to ask directions, as a panhandler advances on you straight up the sidewalk to bar your way. They gazed ruefully at the floor of their car, where empty bottles rolled, and clanked away. I started the car; it was stuck in the mud a foot deep. I sighed in the rainy Texas wilderness.

"Dean," I said, "wake up."

"What?"

"We're stuck in the mud."

"What happened?" I told him. He swore up and down. We put on old shoes and sweaters and barged out of the car into the driving rain. I put my back on the rear fender and lifted and heaved; Dean stuck chains under the swishing wheels. In a minute we were covered with mud. We woke up Marylou to these horrors and made her gun the car while we pushed. The tormented Hudson heaved and heaved. Suddenly it jolted out and went skidding across the road. Marylou pulled it up just in time, and we got in. That was that- the work had taken thirty minutes and we were soaked and miserable.

I fell asleep, all caked with mud; and in the morning when I woke up the mud was solidified and outside there was snow. We were near Fredericksburg, in the high plains. It was one of the worst winters in Texas and Western history, when cattle perished like flies in great blizzards and snow fell on San Francisco and LA. We were all miserable. We wished we were back in New Orleans with Ed Dunkel. Marylou was driving; Dean was sleeping. She drove with one hand on the wheel and the other reaching back to me in the back seat. She cooed promises about San Francisco. I slavered miserably over it. At ten I took the wheel-Dean was out for hours-and drove several hundred dreary miles across the bushy snows and ragged sage hills. Cowboys went by in baseball caps and earmuffs, looking for cows. Comfortable little homes with chimneys smoking appeared along the road at intervals. I wished we could go in for buttermilk and beans in front of the fireplace.

At Sonora I again helped myself to free bread and cheese while the proprietor chatted with a big rancher on the other side of the store. Dean huzzahed when he heard it; he was hungry. We couldn't spend a cent on food. "Yass, yass," said Dean, watching the ranchers loping up and down Sonora main street, "every one of them is a bloody millionaire, thousand head of cattle, workhands, buildings, money in the bank. If I lived around here I'd go be an idjit in the sagebrush, I'd be jackrabbit, I'd lick up the branches, I'd look for pretty cowgirls-hee-hee-hee-hee! Damn! Bam!" He socked himself. "Yes! Right! Oh me!" We didn't know what he was talking about any more. He took the wheel and flew the rest of the way across the state of Texas, about five hundred miles, clear to El Paso, arriving at dusk and not stopping except once when he took all his clothes off, near Ozona, and ran yipping and leaping naked in the sage. Cars zoomed by and didn't see him. He scurried back to the car and drove on. "Now Sal, now Marylou, I want both of you to do as I'm doing, disemburden yourselves of all that clothes-now what's the sense of clothes? now that's what I'm sayin-and sun your pretty bellies with me. Come on!" We were driving west into the sun; it fell in through the windshield. "Open your belly as we drive into it." Marylou complied; unfuddyduddied, so did I. We sat in the front seat, all three. Marylou took out cold cream and applied it to us for kicks. Every now and then a big truck zoomed by; the driver in high cab caught a glimpse of a golden beauty sitting naked with two naked men: you could see them swerve a moment as they vanished in our rear-view window. Great sage plains, snowless now, rolled on. Soon we were in the orange-rocked Pecos Canyon country. Blue distances opened up in the sky. We got out of the car to examine an old Indian ruin. Dean did so stark naked. Marylou and I put on our overcoats. We wandered among the old stones, hooting and howling. Certain tourists caught sight of Dean naked in the plain but they could not believe their eyes and wobbled on.

Dean and Marylou parked the car near Van Horn and made love while I went to sleep. I woke up just as we were rolling down the tremendous Rio Grande Valley through Glint and Ysleta to El Paso. Marylou jumped to the back seat, I jumped to the front seat, and we rolled along. To our left across the vast Rio Grande spaces were the moorish-red mounts of the Mexican border, the land of the Tarahumare; soft dusk played on the peaks. Straight ahead lay the distant lights of El Paso and Juarez, sown in a tremendous valley so big that you could see several railroads puffing at the same time in every direction, as though it was the Valley of the World. We descended into it. - -