#and someone who cares enough to cite obscure novels to back up their points

Text

there’s this one character analysis on Zexion that said he was terrified the whole time he was in the organization and how it’s easy to see in how he acts during his conversation with Xigbar and in his relationships with others in the group that cited a passage from one of the kh short stories talking about how Zexion’s hated Vexen ever since he was human

…except later on in that exact same scene of that short story he has that aforementioned talk with Xigbar and his thoughts are mostly along the lines of “Xigbar is condescending but he’s more obnoxious than anything and I wish he would shut up because his nonsense is wasting my time” which is… not what I’d describe as “acting afraid”

and I just

homie you can’t cite something for an argument when the very source you cited also refutes it

#me post#this is shittalking i’m not tagging it#the nice thing about it though was that it was the only reason I knew the kh short stories existed at all#but like#it’s kind of incredible really#how someone who’s only played kh1 and 2 and ignores everything else#and someone who cares enough to cite obscure novels to back up their points#can end up disrespecting the series the same way#this isn’t about zex anymore this is just in general so it’s contained in one place#so you think kh 3 sucked so bad you’ve decided it isnt canon actually and instead cling to concepts#that were scrapped YEARS ago#because you believe they were the original intent and you like them better#sorry! that’s not what happened! that ship has sailed and then was broken down and recycled into what we actually got#the series will NEVER be what you want it to be. why are you still here#first tumblr i ever blocked was just because i needed to stop myself from intentionally looking at takes that pissed me off lol#and yet here i am still thinking about it

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

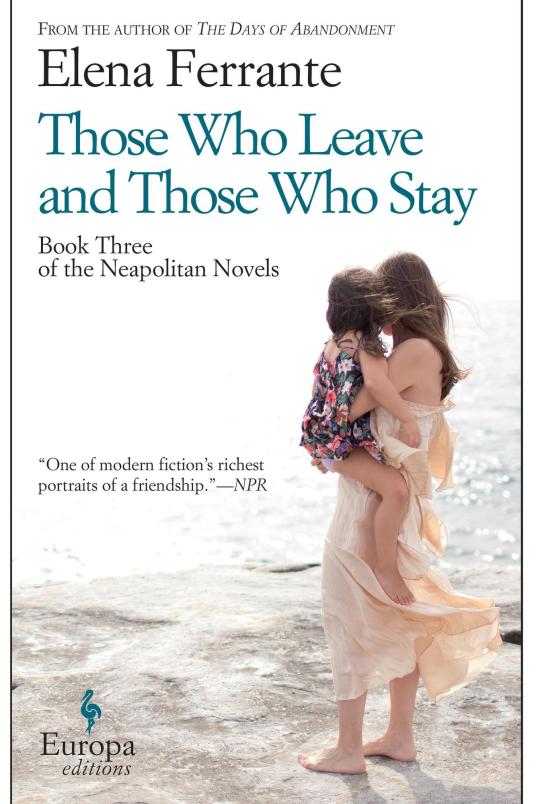

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay: Thoughts

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (Elena Ferrante)

My notes on the first two books from this series: My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name

In Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, Elena and Lila are adults—they’ve both experienced family life, while the same themes of turbulent relationships and societal uprising run throughout the novel. For some reason, I didn’t feel as connected to Elena in this book (I’ve never really felt a connection with Lila). It might have been because I haven’t gotten to that point in life yet—marriage, children seem far off—but I suspect more deeply that Elena’s personality has diverged more and more from her character in the first two books.

Nevertheless, I enjoyed reading about Italy (especially since Elena moved to Florence), and here are some passaged that were particularly striking to me—especially the second to last quote about disguising the naturalness of the body for men:

Elena, using language as a kind of shield in a society she has escaped:

“As soon as I got off the train, I moved cautiously in the places where I had grown up, always careful to speak in dialect, as if to indicate I am one of yours, don’t hurt me.”

Elena, on the irrationality of extracting emotional states from academic performance:

“Studying was considered a ploy used by the smartest kids to avoid hard work. How can I explain to this woman—I thought—that from the age of six I’ve been a slave to letters and numbers, that my mood depends on the success of their combinations, that the joy of having done well is rare, unstable, that it lasts an hour, an afternoon, a night?”

On feelings for women versus feelings for men:

“I admired her, there were no women who stood out in that chaos. The young heroes who faced the violence of the reactions at their own peril were called Rudi Dutschke, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, and, as in war films where there were only men, it was hard to feel part of it; you could only love them, adapt their thoughts to your brain, feel pity for their fate.”

On the transient nature of relationships with men:

“‘A male, apart from the mad moments when you love him and he enters you, always remains outside. So afterward, when you no longer love him, it bothers you just to think that you once wanted him. He liked me, I liked him, the end. It happens to me many times a day—I’m attracted to someone. That doesn’t happen to you? It lasts a short time, then it passes. Only the child remains, he’s part of you; the father, on the other hand, was a stranger and goes back to being a stranger.”

Elena, on achieving grand things but still feeling subdued by others’ ordinary achievements:

“I feel like the knight in an ancient romance as, wrapped in his shining armor, after performing a thousand astonishing feats throughout the world, he meets a ragged, starving herdsman, who, never leaving his pasture, subdues and controls horrible beasts with his bare hands, and with prodigious courage.”

Elena, on her work defining her state of life, and losing the streak of greatness:

“So the things I wrote had no energy, they were merely demonstrations of my formal skill, flourishes lacking substance. Once, having written an article, I had Pietro read it before dictating it to the editorial office. He said: ‘It’s empty.’

‘In what sense?’

‘It’s just words.’

I felt offended, and dictated it just the same. It wasn’t published. And from then on, with a certain embarrassment, both the local and the national editorial offices began to reject my texts, citing problems of space. I suffered, I felt that everything that up to a short time earlier I had taken as an unquestioned condition of life and work was rapidly collapsing around me, as if violently jolted from inaccessible depths. I read just to keep my eyes on a book or a newspaper, but it was as if I had stopped at the signs and no longer had access to the meanings.”

On feeling proud of your journey but at the same time only expressing anger and no pride in regards to inequality:

“I suspected, in those moments, that the words he had shouted before (shut up, you speak in clichés) hadn’t been an accidental loss of temper but indicated that in general he didn’t consider me capable of a serious discussion. It exasperated me, depressed me, my rancor increased, especially because I myself knew that I wavered between contradictory feelings whose essence could be summed up like this: it was inequality that made school laborious for some (me, for example), and almost a game for others (Pietro, for example); on the other hand, inequality or not, one had to study, and do well, in fact very well—I was proud of my journey, of the intelligence I had demonstrated, and I refused to believe that my labor had been in vain, if in certain ways obtuse. And yet, for obscure reasons, with Pietro I gave expression only to the injustice of inequality. I said to him: You act as if all your students were the same, but it’s not like that, it’s a form of sadism to insist on the same results from kids who haven’t had the same opportunities.”

On Pietro’s insecurity and demand for affectionate, supportive attention:

“I was his wife, an educated wife, and he expected me to pay close attention when he spoke to me about politics, about his studies, about the new book he was working on, filled with anxiety, wearing himself out, but the attention had to be affectionate; he didn’t want opinions, especially if they caused doubts. It was as if he were thinking out loud, explaining to himself.”

On being born with everything:

“‘As a girl I would have liked to be like you.’

‘Why? You think it’s nice to be born with everything all ready-made for you?’

‘Well, you don’t have to work so hard.’

‘You’re wrong—the truth is that it seems like everything’s been done already and you’ve got no good reason to do anything. All you feel is the guilt of what you are and that you don’t deserve it.’

‘Better that than to feel the guilt of failure.’”

Elena, on intellectually supporting one stance but wavering when it approaches her own family:

“Only in the elevator did I realize that my entire self had in a sense slid backward. What would have seemed to me acceptable in Milan or Florence—a woman’s freedom to dispose of her own body and her own desires, living with someone outside of marriage—there in the neighborhood seemed inconceivable: at stake was my sister’s future, I couldn’t control myself.”

On comfortableness with people who you feel are lesser:

“And all while Pietro, with that capacity of his for feeling at ease with people he considered inferior, was already saying, without consulting me, that he would very much like to visit the center in Acerra and he wanted to hear about it from Lila, who had sat down again.”

Elena, on the absurdity and irrational urge to "camouflage” herself completely for men:

“In recent years I had begun to be interested in fashion, to educate my taste under Adele’s guidance, and now I enjoyed dressing up. But sometimes—especially when I had dressed not only to make a good impression in general but for a man—preparing myself (this was the word) seemed to me to have something ridiculous about it. All that struggle, all that time spent camouflaging myself when I could be doing something else. The colors that suited me, the ones that didn’t, the styles that made me look thinner, those that made me fatter, the cut that flattered me, the one that didn’t. A lengthy, costly preparation. Reducing myself to a table set for the sexual appetite of the male, to a well-cooked dish to make his mouth water. And then the anguish of not succeeding, of not seeming pretty, of not managing to conceal with skill the vulgarity of the flesh with its moods and odors and imperfections. But I had done it. I had done it also for Nino, recently. I had wanted to show him that I was different, that I had achieved a refinement of my own, that I was no longer the girl at Lila’s wedding, the student at the party of Professor Galiani’s children, and not even the inexperienced author of a single book, as I must have appeared in Milan. But now, enough. He had brought his wife and I was angry, it seemed to me a mean thing. I hated competing in looks with another woman, especially under the gaze of a man, and I suffered at the thought of finding myself in the same place with the beautiful girl I had seen in the photograph, it made me sick to my stomach. She would size me up, study every detail with the pride of a woman of Via Tasso taught since birth to attend to her body; then, at the end of the evening, alone with her husband, she would criticize me with cruel lucidity.”

On the hazy origins of money, no matter how it is obtained:

“I thought of how many hidden turns money takes before high salaries and lavish fees. I remembered the boys from the neighborhood who were paid by the day unloading smuggled goods, cutting trees in the parks, working at the construction sites. I thought of Antonio, Pasquale, Enzo. Ever since they were boys they had been scrambling for a few lire here, a few there to survive. Engineers, architects, lawyers, banks were another thing, but their money came, if through a thousand filters, from the same shady business, the same destruction, a few crumbs had even mutated into tips for my father and had contributed to allowing me an education. What therefore was the threshold beyond which bad money became good and vice versa?”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Studying the narrative of women in Moses, Citizen, & Me

One thing we often forget is that every aspect of our lives contains a narrative. From the movies we watch to the books we read; they all contain some type of carefully woven together time and place of concurrent events. Even natural storytellers who are surrounded by boundless narratives, writing a novel still poses many challenges. Authors must choose carefully the way they put together the events that they’re describing, who narrates the story, and where it takes place or risk the message being lost or misinterpreted. In Moses, Citizen, and Me, the narrative is woven together through the lenses of a foreign women thrust into the aftermath of a civil conflict between the Revolutionary United Front and the government of Sierra Leone. As readers who have no connection to Sierra Leone, we can empathize with narrator: Julia. Just like her, we are outsiders thrust into the conflict, desperate to find our place and what we can do to help. If this book was told from the perspective of a male or someone who never left Sierra Leone the story would be entirely different. Perhaps we wouldn’t see the death of Adele or know about the rehabilitation of Citizen. Maybe the novel would focus specifically on the violence perpetrated through the war instead, we could only imagine because there are an infinite number of ways this story could have been told if the narrator wasn’t Julia. However, since this novel is told through the lens of a woman, I want to focus on this paper on that aspect by talking about Pre- and Post-colonial west Africa, the roles of women, and Julia’s specific role in Moses, Citizen, and Me.

To understand the role of women in the book, you first have to consider where it takes place. This may not seem important but western cultures have different gender roles than Asian or African cultures. With that being said: Moses, Citizen, and Me takes place in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, a country in West Africa. Freetown was established in 1792 by free blacks, Caribbean’s, and Africans. Without the western influences of patriarchy created by slavery and racism, a melting pot of unique African and Caribbean culture was able to form. However, in 1808 that all changed when Freetown became a crown colony of Great Britain. Although the conquest of Freetown happened significantly earlier, the scramble for Africa changed the entire culture. In order to survive now, West Africans were forced to adopt new ideologies. This can be seen in books like Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong'o's Weep Not, Child. These new ideologies severely changed not only the role of women in west Africa but also the overall culture. In Pre-colonial West Africa “West African women and the spiritual female principal during the long precolonial period the power and right to give orders, make decisions, and enforce obedience in short they had authority.” (History Textbook).. However, as Africa was colonized, Western men saw women in positions of power as disgraceful and placed them in roles ‘more suited’ to women. “History has been obscured by western patriarchal ideologies which imagined west African women as a beast of burden.” (History Textbook) Gone is the tradition of women being involved in politics and having the same authority as men.

Sierra Leone was freed from British colonial rule in 1961. From 1967 to 1985 Sierra Leone was a one-party state. In 1971 the government abolished Sierra Leone's parliamentary government system and declared Sierra Leone a presidential republic. (Britannica) With all this inner turmoil in Sierra Leone, women are unable to find a role that’s comfortable for them and the culture becomes even more torn and fragmented. The civil war in 1991 however adds another role. They are forced into being child soldiers, with both their child and womanhood taken from them. They are killed destroying the matriarchy. “It was a woman. Her hands were tied behind her back and her legs were bound together, there were several bullets in her back. It was Adele, his own grandmother.” (Macauley 2) Choice is stolen from them and disobedience is met with violence. “He turned and hit her hard across the head, so she fell to the ground where her chin hit the bottle. Holding her jaw, she struggled to her feet and stood behind him.” (Macauley 64). Finally, they are made into beings used for sexual gratification and objectification. “The lieutenant touched his ‘wife’ on the buttocks and kissed her on the neck, indicating that it was time to move on.” (Macauley 65). Julia our narrator shows us the brutal affects not only this war, but all the political turmoil has caused for the women of Sierra Leone.

“Maybe it wasn’t your plan, but you could help them, both of them. Did you know that?” (Macauley 320) The novel takes place in Freetown after the civil war. Women finally trying to shift into all three roles and find a place between post and pre-colonial culture that works for them. Julia, who has no idea of any of this, having been born in London, is surprised when she first arrives in Freetown. She is immediately subjected to taking over her aunt Adele’s role as homemaker. It’s her place, a role that’s already been ordained for her. “But he needs care. Someone who would care. Someone like you.” (Macauley 16) She is stubborn. This is her story and she’s going to be the one to tell it. It’s not in her nature to be a caretaker, she wants to make something of her life that’s more than being a trauma rehabilitation center. “Mummy I’ve been thinking I might go abroad at the end of this year.” (Macauley 100). She also states she isn’t ready to give up the things she’s worked so hard in life to secure like the women around her. She feels angry and disappointed with her family, Moses especially, trying to her make her take on this responsibility. “I felt disappointed. I could not imagine any other emotions again. Why could he not understand me and support me? Why did he not see that I was trying to find my way here? I gripped my Paris dream hard.” (Macauley 104) Her uncle, stricken by grief, unknowing names Julia as a replacement for Adele. It’s her job to rehabilitate her nephew Citizen and she is fiercely averse to taking the role. “‘Oh, does he? I thought he’d need people here; people who understand what’s happening to boys like him what they’ve been through.” (Macauley 16).

To me Julia isn’t just our narrator, she also serves as a thematic character, representing this change between old ideas of western Africa, the influence Europe, and the aftereffects the civil war had on Sierra Leone. She’s a representation of the struggle to re-embrace one’s roots or adapt to new times and cultural normativism. “‘That’s how my mother made it and that’s how aunt sally showed her how to make it.’/ ‘We don’t make it like that anymore’. She said. ‘That’s so old fashioned’ she stood up and walked over to the cupboard that I had barely noticed before. From it she took a jar which was put down in front of me. A jar of peanut butter. ‘This is what we do now.’ “(Macauley 82) Initially, Julia rejects her role as a cultural martyr and consequently her character becomes purposeless in the novel. She has no reason to be Freetown as she has rejected the new culture.

Julia is a memetic character in the sense that she is constantly tied between taking her ‘destined’ role in Freetown and or maintaining comfort in being a European woman. Although she rejects the role the pressure from the environment eventually is able to break her down. She represents the struggle between the old world and new world and her rejection of rehabilitating Citizen takes away her ability to fit in. She sticks out like a sore thumb, while the other women work closely with the child soldiers, Julia is fearful and rejects them. However as much as she rejects this role, she is also desperate to fit it. She is desperate to know her African self and roots and find a place for herself that she never found in England. So desperate that she changes her mind and accepts her role as Citizen’s caretaker. The women in the novel have also seemed to do the same. They are no longer the powerful political figures the history books talk about. They’ve been complicit and accepting of the European idea of what a woman should be and what her role and place in society is. Just like Julia, they are memetic, and all symbolize something greater: the mother figure of Sierra Leone in its entirety (Adele), homemaker/housewife (Anita), and heroine/rescuer of Sierra Leone’s broken children. (Elizabeth). This would make Julia seem as the hero of her story. She’s the only one brave enough to stand up against her ‘destiny’ while women such as Adele and Anita, while having an essential role in the culture, are confined to a more European role. Yet she also gives way to complicity making her unreliable as a character and narrator.

This may seem unimportant to narrative and narrative theory but it’s actually what makes the narrative. As the audience we follow live through her experiences as told by her. Narrative is more than a simple story but rather a time and place of events. With Julia we see things as though she there with Citizen, she gives an opportunity to understand his part in the war, the opportunity to empathize with him. If these events were recounted by Moses perhaps it would be filled with hatred or anger. Also important to the story is the focal point, it’s strictly told after the civil war has wrapped up. Although she gives us breaks from this strictness when she’s showing the war through Citizen’s eyes and flashbacking to her time in Europe. Narrative also helps us realize that character often times have depth and dimension: Julia, Adele, and Anita are memetic in the way that they all represent something larger upon further inspection. Without them we have no story to tell.

Works cited:

“11: Women and Authority in West African History.” History Textbook, wasscehistorytextbook.com/11-women-and-authority-in-west-african-history/.

“All People's Congress.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/topic/All-Peoples-Congress.

Jarrett-Macauley, Delia. Moses, Citizen & Me. Granta, 2006.

0 notes